Abstract

A 69-year-old woman with 26-year history of systemic lupus erythematosus and 4-year history of peritoneal dialysis was hospitalized for treatment of bacterial peritonitis. On admission, peritoneal dialysate was collected and subjected to bacterial culture. Cell count in the cloudy peritoneal dialysate was 4194/μL, and Gram-negative bacilli were detected. Vancomycin (1 g/day) and ceftazidime (1 g/day) were administered intraperitoneally, which resulted in rapid decrease in cell count in the peritoneal dialysate. However, on the 7th hospital day, peritonitis relapsed with abdominal pain and cloudy dialysate. 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing analysis identified Stappia indica sp. as the causative bacteria. Although treatment with 1 g/day meropenem for an additional 3 weeks was effective, bacterial peritonitis relapsed 7 days after its discontinuation. Because biofilm formation was suspected, the peritoneal catheter was removed, and she was transferred to maintenance hemodialysis. After removal of the peritoneal catheter, bacterial peritonitis never relapsed. Stappia indica was initially discovered in the deep seawater of the Indian Ocean. The bacterium is rod-shaped, Gram-negative, and oxidase- and catalase-positive. There have been no reports on the clinical effects of genus Stappia. Given the frequent relapse in the present case, Stappia indica sp. may easily form biofilms and are likely resistant to antibiotics. Timely peritoneal catheter removal may be required in some cases of bacterial peritonitis as in the present case. Further case reports are required to further elucidate the clinical effects of Stappia indica on humans.

Keywords: Peritoneal dialysis, Relapsing peritonitis

Introduction

Bacterial peritonitis is a common and devastating complication in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis (PD) [1]. Furthermore, according to previous reports, it remains an important cause of mortality in such patients [2]. Peritonitis is also a major cause of PD technical failure and transfer from PD to hemodialysis. Accordingly, as per International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis guidelines [3], prevention and timely intervention are necessary to lower the risk of peritonitis-related mortality in patients undergoing PD.

The causes of bacterial peritonitis vary and depend on the source of infection, including touch contamination, exit-site infection, bloodstream infection, and progression from site of infection in the abdomen [3]. However, uncommon bacteria may be the cause of peritonitis in some cases [4–6]. Additionally, some bacterial genera are resistant to antibiotics frequently used as empiric treatment in cases of bacterial peritonitis in patients undergoing PD [7].

Here, we present the case of a PD patient who developed bacterial peritonitis induced by Stappia indica sp., which was confirmed by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing analysis. The patient required peritoneal catheter removal and transfer to hemodialysis therapy to cure recurrent peritonitis.

Case report

A 69-year-old woman with a 26-year history of systemic lupus erythematosus treated with 2.5 mg/2 days prednisolone and 4-year history of PD was hospitalized for treatment of bacterial peritonitis. She was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus at age 43. At age 55, she developed nephrotic syndrome and underwent percutaneous kidney biopsy, which resulted in histological diagnosis of lupus nephritis (World Health Organization Class IV). Oral prednisolone (50 mg/day) induced partial remission of nephrotic syndrome. However, her lupus nephritis-induced chronic kidney disease was progressive. At age 65, she developed end-stage kidney disease and was started on PD. She also underwent percutaneous intervention for coronary artery disease at age 65. Over the previous 4 years, she experienced three prior episodes of bacterial peritonitis. The causative pathogens were Enterococcus species, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Streptococcus species α. One episode of bacterial peritonitis was related to touch contamination, while the other two were likely related to bacterial translocation via the gut. She was treated using continuous ambulatory PD with exchange of 2-L bags four times per day. In actuality, during the last 4 years, the patient and her family did not travel overseas or go near a sea, seaside, or river, where she might have been infected with water-dwelling bacteria. However, as is frequent with Japanese homemakers, they often cook fresh fish for dinner. Therefore, the patient might have been infected by sea-dwelling bacteria residing on a Fish’s scale. On the day of admission, she suddenly developed general fatigue, lower abdominal pain, and a cloudy peritoneal dialysate, and was admitted for treatment of bacterial peritonitis.

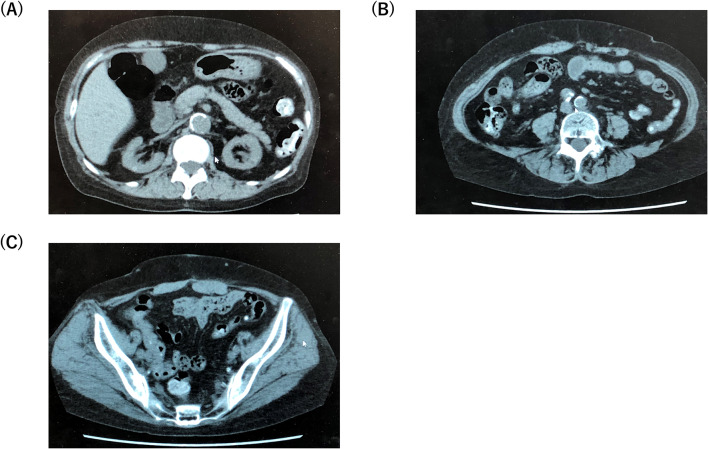

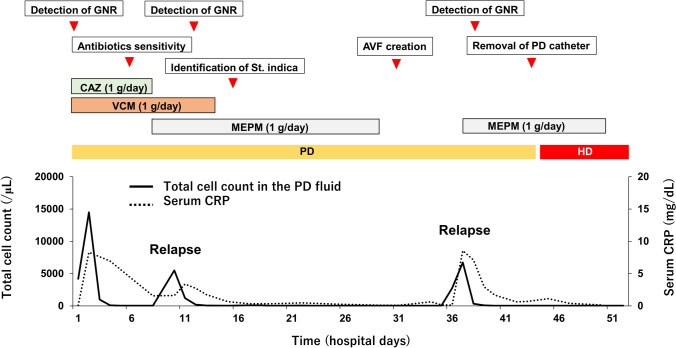

On admission, the patient was alert. Her blood pressure was 194/108 mmHg, heart rate was 88 beats/min, and body temperature was 35.8 °C. Physical examination revealed she was experiencing a moderate degree of abdominal pain and tenderness. Her exit site and catheter tunnel showed no evidence of infection. Laboratory data on admission revealed a white blood cell count of 11,220/μL with 83.3% segmented neutrophils and C-reactive protein level of 0.09 mg/dL. Serum procalcitonin was negative. A summary of laboratory data on admission is shown in Table 1. The dialysate fluid cell count was 4194 white blood cells/μL. Gram stain of the cloudy peritoneal dialysate revealed Gram-negative bacilli (Fig. 1), whereas Ziehl–Neelsen stain of the dialysis fluid was negative. To identify the causative bacteria, we collected PD fluid from the PD bag (that dwelled in the abdominal cavity of the patient) in 10-mL or 50-mL sterilized tubes. Next, cloudy PD solution in the tubes was centrifuged, resuspended with saline, and plated on standard sheep blood agar plates. Additionally, 10 mL of cloudy PD solution was incubated in a blood culture bottle. Once bacterial colonies were formed, they were then submitted for conventional biochemical analyses to determine the bacteriological features of the bacterium and to group it into a known bacterial genus. Blood culture was also negative. A tentative diagnosis of bacterial peritonitis was established, and the patient was treated empirically with intraperitoneal administration of 1 g/day ceftazidime and 1 g/day vancomycin. Three days after starting treatment with the two antibiotics, cell count in the peritoneal dialysate decreased and fever and abdominal pain subsided. Although the causative bacterium formed colonies on the agar plate, standard biochemical analysis failed to identify the genus, and the sample was then subjected to matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MLADI-TOF) mass spectrometry. However, mass spectrometry also failed to identify the genus, and the sample was sent for 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing analysis. On the 7th hospital day, results of the susceptibility test were returned and showed the causative bacterium was susceptible to ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, meropenem, and doripenem, and resistant to penicillin, piperacillin, cefoperazone, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and vancomycin. Therefore, we continued intraperitoneal administration of ceftazidime (Table 2). However, on the 10th hospital day, her serum C-reactive protein level was re-elevated, cell count in the peritoneal dialysate increased to 5498 cells/μL, and gram-negative bacilli were again detected, suggesting flare-up of bacterial peritonitis by the same organism, namely, relapsing peritonitis. To rule out the possibility of intestinal perforation, contrast-enhanced computed tomography was performed, but no evidence of perforation was found. At this point, ceftazidime was ineffective against the Gram-negative bacilli. Therefore, we replaced ceftazidime with meropenem and subsequently discontinued vancomycin. On the 16th hospital day, the results of 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing analysis were returned and revealed that the causative organism was Stappia indica sp. Intraperitoneal administration of meropenem was continued for a total of 21 days, resulting in a normalized cell count in the peritoneal dialysate and negative culture at the end of the therapy. Given the three distinct prior episodes of bacterial peritonitis, we discontinued PD and initiated hemodialysis to lower the risk of developing encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, and established an arteriovenous fistula on her right forearm on the 30th hospital day. However, on the 37th hospital day (7 days after discontinuing meropenem), peritonitis recurred. The bacteria detected from the cloudy dialysate were Gram-negative bacilli and later reconfirmed as Stappia indica. Because repeated relapse of bacterial peritonitis under sensitive antibiotics treatment was observed, biofilm formation was highly suspected. Accordingly, the peritoneal catheter was surgically removed on the 43rd hospital day. Macroscopically, the removed catheter did not show apparent biofilm formation. Then, computed tomography was performed, and no infection source including intra-abdominal abscess was detected (Fig. 2). To further determine whether biofilm formation was present, the tip of the removed PD catheter was cut at the tip and cultured by being submerged in the liquid medium in order that the bacteria in the biofilm located in both inner and outer surfaces of the PD catheter could easily access the medium and yield a positive culture.

Table 1.

Laboratory data on admission

| Complete blood counts | HDL cholesterol | 62 | mg/dL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 10.6 | g/dL | LDL cholesterol | 116 | mg/dL |

| Hematocrit | 34.3 | % | Triglyceride | 141 | mg/dL |

| White blood cells | 11,220 | /µL | Others | ||

| Neutrophils | 83.3 | % | HbA1c | 5.3 | % |

| Platelets (× 105) | 31.6 | /µL | Glycoalbumin | 11.5 | % |

| β2 microglobulin | 22.6 | mg/L | |||

| Serum biochemistries | |||||

| Total protein | 5.8 | g/dL | Immunological studies | ||

| Albumin | 3.1 | g/dL | C3 | 91 | mg/dL |

| Urea nitrogen | 54 | mg/dL | C4 | 25 | mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 8.8 | mg/dL | CH50 | 148 | U/mL |

| Uric acid | 5.7 | mg/dL | Anti-nuclear antibody | × 320 | |

| Total bilirubin | 0.4 | mg/dL | Anti-dsDNA-antibody | ( −) | |

| Glucose | 101 | mg/dL | Anti-HBs antigen | ( −) | |

| C-reactive protein | 0.09 | mg/dL | Anti-HBs antibody | ( −) | |

| Calcium | 8.7 | mg/dL | Anti-HCV antibody | ( −) | |

| Phosphorus | 5.0 | mg/dL | Procalcitonin | ( −) | |

| Sodium | 139 | mmol/L | Endocrinological studies | ||

| Potassium | 4.9 | mmol/L | Intact PTH | 86.4 | pg/mL |

| Chloride | 101 | mmol/L | Brain natriuretic hormone | 683 | Pg/mL |

| AST | 10 | U/L | Coagulation | ||

| ALT | 5 | U/L | PT-INR | 1.00 | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 199 | U/L | APTT | 29.4 | sec |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 111 | U/L | Urine test | ||

| Amylase | 22 | U/L | Specific gravity | 1.019 | |

| Creatine kinase | 33 | U/L | Proteinuria | 3 + | |

| Iron | 91 | µg/dL | Hematuria | ( −) | |

| UIBC | 166 | µg/dL | Ketone | ( −) | |

| Ferritin | 73.8 | ng/mL | White blood cells | 2 + | |

| Total cholesterol | 219 | mg/dL | Nitrite reaction | ( −) | |

ALT arginine aminotransferase; APTT activated partial thromboplastin time; AST aspartate aminotransferase; C complement; dsDNA double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid; HBs hepatitis B surface; HCV hepatitis C virus; HDL high-density lipoprotein; LDL low-density lipoprotein; PTH parathyroid hormone; PT-INR prothrombin time-internationalized ratio; UIBC unsaturated iron binding capacity

Fig. 1.

Gram staining of bacteria detected in cloudy peritoneal dialysate fluid. Gram stain of the pellet obtained after centrifugation of the cloudy peritoneal dialysate fluid on the first hospital day revealed Gram-negative rods

Table 2.

Sensitivity of Stappia indica to common antibiotics in the patient

| Name of antibiotics | MIC (mU/mL) |

|---|---|

| PIPC | 16 |

| CPZ/SBT | ≤ 8 |

| PICP/TAZ | ≤ 16 |

| CAZ | 4 |

| CFPM | 2 |

| CZOP | ≤ 0.5 |

| IPM/CS | ≤ 0.25 |

| MEPM | ≤ 0.25 |

| DRPM | ≤ 0.25 |

| AZT | ≥ 32 |

| GM | ≥ 16 |

| TOB | ≥ 16 |

| AMK | 2 |

| MINO | ≤ 0.25 |

| FOM | ≥ 256 |

| CPFX | 0.06 |

| LVFX | ≤ 1 |

| VCM | 16 |

| ST | ≤ 20 |

AMK amikacin; AZT aztreonam; CAZ ceftazidime; CFPM cefepime; CPFX ciprofloxacin; CPZ/SBT cefoperazone/sulbactam; CZOP cefozopran; DRPM doripenem; FOM fosfomycin; GM gentamycin; IPM/CS imipenem/cilastatin; LVFX levofloxacin; MIC minimally inhibitory concentration; MINO minomycin; PICP/TAZ piperacillin/tazobactam; R resistance; S sensitive; ST sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim; TOB tobramycin; VCM vancomycin

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography scanned just after the removal of the PD catheter. Computed tomography captured at the levels of (a) kidney, (b) aortic bifurcation, and (c) pelvis. PD peritoneal dialysis

Additional 2 weeks of meropenem treatment was administered. In addition, she was transferred from PD to maintenance hemodialysis on the 44th hospital day. However, no bacterial growth was observed. At this point, even following discontinuation of meropenem, bacterial peritonitis never relapsed. She was discharged on the 52nd hospital day. She is currently on maintenance hemodialysis without relapse of bacterial peritonitis. The clinical course during hospitalization is summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Clinical course during hospitalization. AVF arteriovenous fistula; CAZ ceftazidime; CRP C-reactive protein; GNR Gram-negative rod; HD hemodialysis; MEPM meropenem; PD peritoneal dialysis; St. Stappia; VCM vancomycin

Discussion

Herein, we report a case of bacterial peritonitis induced by Stappia indica sp. The causative organism was identified by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing analysis and the infection was successfully treated with meropenem and peritoneal catheter removal. The present case has several clinical implications. First, Stappia indica sp. can induce bacterial peritonitis in PD patients. Second, this is the first report of antibiotic sensitivity patterns of Stappia indica sp. Stappia indica sp. exhibit resistance to several types of antibiotics, which can lead to treatment failure if third-generation cephem antibiotics are selected to cover Gram-negative bacilli. Third, Stappia indica sp. cannot be identified using routine laboratory techniques and require 16S rRNA gene sequencing for identification, making it difficult to promptly diagnose bacterial peritonitis induced by these organisms.

Stappia indica was initially discovered in the deep seawater of the Indian Ocean [8]. This species belongs to genus Stappia, in the family Rhodobacteraceae. To date, several species of Stappia have been reported. Stappia stellulatum, Stappia aggregate, Stappia alba, Stappia marinamano, Stappia carboxidovorans, Stappia conradae, Stappia kahanamokuae, and Stappia meyerae. They are Gram-negative, oxidase- and catalase-positive, rod-shaped, and motile by means of one polar flagellum. The detailed features of Stappia indica were described previously [8, 9]. Because the genus Stappia cannot be identified using standard biological methods, 16S rRNA gene sequencing must be used and is an important and reliable method. However, 16S rRNA gene sequencing is expensive and time-consuming. Accordingly, the optimal clinical approach would be to transfer the specimen for 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing or mass spectrometry once bacterial peritonitis is encountered (and when the causative bacteria is confirmed by Gram staining but not categorized into a known specific bacterial genus by the conventional biochemical approach). However, I do not believe that all cases of bacterial peritonitis caused by unknown bacterial species should be identified, insofar as bacterial peritonitis is being controlled by standard antibiotic treatment.

Notably, there have been no reports on bacterial peritonitis or other infections caused by genus Stappia. A previous report showed that Stappia indica sp. caused black band disease in coral [10]. Although at present, the pathogenesis of Stappia indica sp. infection is poorly understood, a possible association between water contamination and Stappia indica infection should be considered, given that genus Stappia is often detected in seawater and affects sea plants [11–14]. In the present case, the patient was a housewife and was not involved in work with significant exposure to seawater. In actuality, during the last 4 years, the patient and her family did not travel overseas or go near a sea, seaside, or river, where she might have been infected with water-dwelling bacteria. It is, therefore, unknown how Stappia indica entered the patient and caused bacterial peritonitis. Furthermore, a previous report suggests Stappia indica can form biofilms [15], indicating potential for resistance to antimicrobial therapy. Macroscopically, biofilm was not observed on the surface of the removed PD catheter and culture of the tip of the removed PD catheter did not reveal Stappia indica in the present case. However, previous studies have shown that analysis by the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) could detect biofilm formation on the surface of the PD catheter [16]. It would be possible that our case developed biofilm formation of the PD catheter, which could only be detected by the TEM. Accordingly, when biofilm formation was highly suspected clinically, TEM would be a useful option to confirm biofilm formation of the PD catheter.

The empirical antibiotic regimen for peritonitis in patients on PD generally includes a cephalosporin to cover gram-negative bacilli. However, the Stappia genus is estimated to exert antibiotic resistance, with significant resistance to penicillins and cephalosporins. In our case, Stappia indica was sensitive to fluoroquinolones and carbapenems, but resistant to gentamycin, penicillins, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and vancomycin. Stappia indica was previously shown to be sensitive to carbenicillin, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, gentamicin, kanamycin, neomycin, norfloxacin, ofloxacin, and rifampicin, but resistant to ampicillin, penicillin G, piperacillin, cefalexin, cefazolin, Rocephin, clindamycin, lincomycin, metronidazole, oxacillin, polymyxin, streptomycin, tetracycline, vibramycin, and vancomycin [8]. The general sensitivity of genus Stappia should be further examined. In contrast, genus Stappia is susceptible to fluoroquinolones and carbapenems. The standard treatment regimen may fail in cases of bacterial peritonitis caused by genus Stappia. Additionally, the mechanisms for resistance of Stappia indica sp. to certain antibiotics, such as penicillins, cephalosporins, and vancomycin, remain unknown and should be investigated in future studies.

In conclusion, we present the first report of bacterial peritonitis caused by Stappia indica sp. in a patient undergoing PD. When treating single-organism Gram-negative peritonitis, Stappia indica sp. should be considered as causative bacteria, especially when the patients have increased risk of being contaminated by bacteria dwelling in the sea, although the incidence rate associated with this organism may be very low. Importantly, Stappia indica may easily form biofilms, and timely peritoneal catheter removal may represent a viable therapeutic option. Additionally, antibiotic therapy should be adjusted to the sensitivity pattern of the antibiotics, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis may be necessary for identifying the causative organism with high probability.

Acknowledgements

We thank Richard Robins, PhD, from Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanzgroup.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest exist.

Human and animal rights

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Written informed consent for submitting this case report to medical journals was obtained by the patient.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pérez Fontan M, Rodríguez-Carmona A, García-Naveiro R, Rosales M, Villaverde P, Valdés F. Peritonitis-related mortality in patients undergoing chronic peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25(3):274–284. doi: 10.1177/089686080502500311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boudville N, Kemp A, Clayton P, Lim W, Badve SV, Hawley CM, McDonald SP, Wiggins KJ, Bannister KM, Brown FG, Johnson DW. Recent peritonitis associates with mortality among patients treated with peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(8):1398–1405. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011121135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, de Arteaga J, Fan S, Figueiredo AE, Fish DN, Goffin E, Kim YL, Salzer W, Struijk DG, Teitelbaum I, Johnson DW. ISPD peritonitis recommendations: 2016 update on prevention and treatment. Perit Dial Int. 2016;36(5):481–508. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2016.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsukuma Y, Sugawara K, Shimano S, Yamada S, Tsuruya K, Kitazono T, Higashi H. A case of bacterial peritonitis caused by roseomonas mucosa in a patient undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. CEN Case Rep. 2014;3(2):127–131. doi: 10.1007/s13730-013-0101-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helvaci O, Hızel K, Guz G, Arinsoy T, Derici U. A very rare pathogen in peritoneal dialysis peritonitis: serratia liquefaciens. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2019;30(3):738–740. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.261363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho Y, Struijk DG. Peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis: atypical and resistant organisms. Semin Nephrol. 2017;37(1):66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song SH, Choi HS, Ma SK, Kim SW, Shin JH, Bae EH. Micrococcus aloeverae – a rare cause of peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis confirmed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. J Nippon Med Sch. 2019;86(1):55–57. doi: 10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2019_86-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai Q, Qiao N, Wu C, Sun F, Yuan J, Shao Z. Stappia indica sp. nov., isolated from deep seawater of the Indian Ocean. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:733–736. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.013417-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber CF, King GM. Physiological, ecological, and phylogenetic characterization of Stappia, a marine CO-oxidizing bacterial genus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(4):1266–1276. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01724-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henao J, Pérez H, Abril D, Ospina K, Piza A, Botero K, Rincón C, Donato J, Hurtado A, García E, Otero V, Del Risco A, Guerra B, Cifuentes Y, Ordoñez A, Rojas D, Suarez K, Osorio D, Pinzón A. Genome sequencing of three bacteria associated to black band disease from a Colombian reef-building coral. Genom Data. 2016;11:73–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gdata.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen WM, Sheu FS, Arun AB, Young CC, Sheu SY. Stappia aquimarina sp. nov., isolated from seawater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011;18:1763. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.030643-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim BC, Park JR, Bae JW, Rhee SK, Kim KH, Oh JW, Park YH. Stappia marina sp. nov., a marine bacterium isolated from the yellow sea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56(1):75–79. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63735-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kämpfer P, Arun AB, Frischmann A, Busse HJ, Young CC, Rekha PD, Chen WM. Stappia taiwanensis sp. nov., isolated from a coastal thermal spring. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63(Pt 4):1350–1354. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.044966-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pujalte MJ, Macián MC, Arahal DR, Garay E. Stappia alba sp. nov., isolated from mediterranean oysters. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2005;28(8):672–678. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao Y, Zheng Y, Wu S, Zhang EH, Chen Z, Liang P, Huang X, Yang ZH, Ng IS, Chen BY, Zhao F. Pyrosequencing reveals a core community of anodic bacterial biofilms in bioelectrochemical systems from China. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1410. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bosma JW, Siegert CE, Peerbooms PG, Weijmer MC. Reduction of biofilm formation with trisodium citrate in haemodialysis catheters: a randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(4):1213–1217. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]