Abstract

A 32-year-old Japanese woman at 8 weeks of gestation was admitted to our hospital for systemic edema, hypoalbuminemia, and severe proteinuria. The patient had a history of generalized alopecia and migraine. We diagnosed nephrotic syndrome, and renal biopsy revealed minimal change nephrotic syndrome (MCNS). We administered 1000 mg/day of methylprednisolone for 3 days. Oral corticosteroid therapy was followed by 40 mg of prednisolone daily. We carefully selected concomitant medication after considering organogenesis. Before and after renal biopsy, we administered heparin, antithrombin III, and immunoglobulin agents as appropriate. The patient achieved complete remission on day 8 of treatment and gave birth to a boy at 37 weeks of gestation without recurrence. MCNS during pregnancy is rare, and there is no established treatment. In conclusion, we present a case of a pregnant woman with MCNS during organogenesis. Early treatment initiation can provide a good prognosis for both mother and child.

Keywords: Minimal change nephrotic syndrome, Pregnancy, Generalized alopecia

Introduction

When proteinuria appears before 20 weeks of gestation, renal disease should be considered rather than preeclampsia. Nephrotic syndrome rarely presents during pregnancy. The incidence of nephrotic syndrome in pregnant women is 0.012–0.025% [4]. Pregnancy may accelerate the progression of maternal kidney disease. Even if renal insufficiency and uncontrolled hypertension are absent, pregnant women with nephrotic syndrome are at a high risk of developing both maternal and fetal complications.

Minimal change nephrotic syndrome (MCNS) is a common disease observed in 70–90% of children with nephrotic syndrome and 15% of adults.

Here, we report a case of MCNS in a pregnant woman who achieved complete remission from nephrotic syndrome using corticosteroids. The woman successfully delivered the fetus.

Case report

A 32-year-old Japanese woman at 8 weeks of gestation was admitted to our hospital for systemic edema, hypoalbuminemia, and severe proteinuria. She had been undergoing fertility treatment, and this pregnancy was her first. She had a history of generalized alopecia and migraine. She developed a generalized alopecia two years ago. Seen by a dermatologist, there was no erythema, purpura, or photosensitivity, and no diagnosis of systemic diseases such as SLE or thyroid disease was made. Although one course of steroid pulse therapy was administered, it was not effective. Thereafter, she was treated with cephalantine, antihistamines, and topical steroids, and her condition gradually improved. She had used acetaminophen and triptans occasionally for migraine prior to her pregnancy but had not taken any medication during her pregnancy. She has not used NSAIDs. She had no history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal disease, or abnormal urinalysis. She had no history of atopy or bronchial asthma but was allergic to kiwifruit and buckwheat. At 6 weeks of gestation, the patient noticed sudden pretibial edema, which gradually spread to her face and upper limbs. There were no prior infections. She gained 4 kg in 1 week despite not being able to eat due to hyperemesis gravidarum. She was referred to a nephrology specialist by her gynecologist for close examination and treatment.

On admission, the patient was 155.5 cm tall and weighed 54.2 kg. The patient’s weight increased by 8 kg in 2 weeks. Her blood pressure was 124/86 mmHg, and her oxygen saturation was 97%. Chest X-ray showed bilateral pleural effusion, and abdominal echocardiography showed ascites. The fetus was growing well. Urinalysis revealed a urinary protein concentration of 10.35 g/gCr by spot urine and no hematuria. Serum albumin concentration was 1.2 g/dL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration was 287 mg/dL, immunoglobulin (Ig) G concentration was 167 mg/dL, Ig E concentration was 1,680 IU/mL, and serum creatinine was unchanged from baseline at 0.66 mg/dL. Autoantibodies and various viral tests were negative, there was no decline in complement, and glycated hemoglobin was normal. The selectivity index was 0.16, indicating high protein selectivity.

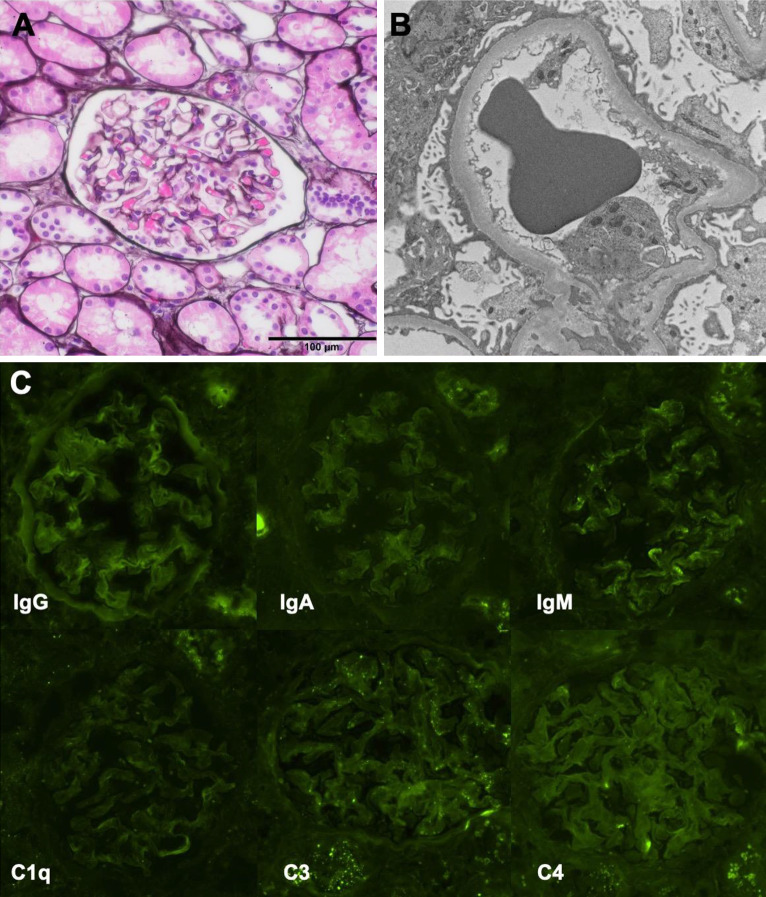

We suspected MCNS because of the rapid disease course and the presence of highly selective proteinuria. The differential diagnosis was focal segmental glomerular sclerosis, membranous nephropathy, and lupus nephritis from a history of alopecia. To confirm the diagnosis and select appropriate treatment, percutaneous renal biopsy was performed at 8 weeks of gestation. Using light microscopy, 25 glomeruli were imaged, and no abnormal findings were apparent (Fig. 1a). Immunofluorescence showed no deposits of Ig A, Ig G, Ig M, or C3, C4, and C1q (Fig. 1c). Electron microscopy showed extensive foot process effacement and no electron-dense deposits (Fig. 1b). On the basis of the above, the patient was diagnosed with MCNS.

Fig. 1.

Pathological findings of renal biopsy. (a) PAM stain shows no abnormalities in glomerulus. (b) Electron microscopy shows extensive foot process effacement. (c) Immunofluorescence studies showed no deposits

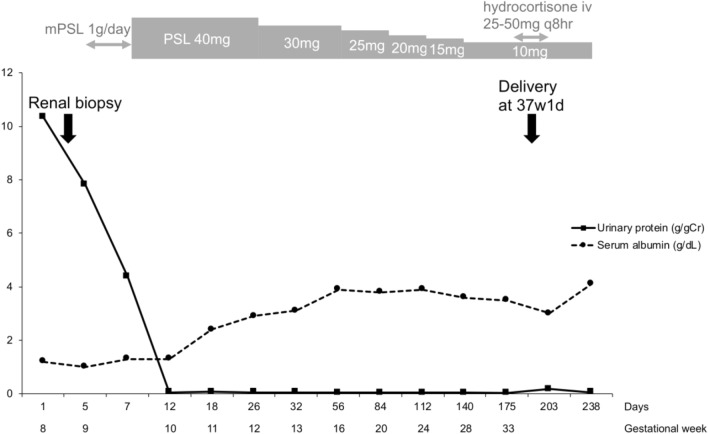

The patient’s clinical course is shown in Fig. 2. We carefully chose appropriate medication after considering the organogenesis period. Before and after renal biopsy, we administered heparin and antithrombin III (AT III) because of hypercoagulability and low AT III. The AT III activity at admission was 60%. Furthermore, we administered Ig agents as appropriate because the patient had low Ig G levels and was at a high risk of infection. The day after the renal biopsy, we administered 1000 mg/day of methylprednisolone for 3 days. We chose the steroid pulse therapy because we believed that oral corticosteroid might be poorly absorbed due to intestinal edema. Oral corticosteroid therapy was followed by 40 mg of prednisolone daily (0.88 mg/kg/day). To control systemic edema, we restricted salt and fluid intake and administered furosemide. Complete remission was achieved on the 12th hospital day, and the patient’s weight gradually decreased. Prednisolone was reduced to 30 mg from the 26th hospital day. The patient presented with hyperglycemia as a complication of corticosteroids, but her blood glucose was well controlled by insulin. We prophylactically administered sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim with folic acid for pneumocystis pneumonia and lansoprazole for gastrointestinal ulcers. No angiotensin-receptor blockers, statins, bisphosphonates, or other osteoporosis-preventing drugs were administered.

Fig. 2.

The patient’s clinical course

After nephrotic syndrome remission, we began to taper off the steroid dose. At 37 weeks of gestation, oral prednisolone was tapered off to 10 mg. The patient was admitted to hospital due to premature membrane rupture. We induced labor, and a male infant was born at 37 weeks and 1 day of gestation weighing 2502 g. The infant’s Apgar score was 8 at 1 min and 8 at 5 min. During delivery, intravenous hydrocortisone was administered with oral prednisolone (10 mg). After delivery, the patient had an uneventful course without any evidence of relapse, and the infant showed normal growth.

Discussion

When urinary protein appears during pregnancy, it may be a physiological change if it is mild, but if pathological proteinuria (>300 mg/day) persists, close examination is required. If proteinuria occurs after 20 weeks of gestation with hypertension, preeclampsia is diagnosed in most cases. It is indicated that even if only urinary protein is present, the condition may later progress to preeclampsia [1]. Because of the risk of serious complications for both mother and fetus in cases of preeclampsia, salt reduction and antihypertensive drugs are used to reduce blood pressure. In contrast, the appearance of urinary protein in early pregnancy may indicate renal disease. Particularly in patients with nephrotic syndrome, continued hypoalbuminemia increases the likelihood of developing acute kidney injury, which in turn increases the risk of maternal and fetal death and childbirth complications [2]. Castro et al. reported that in pregnant women who developed the nephrotic syndrome, high levels of urinary protein were associated with the risk of childbirth complications, even in the absence of acute kidney injury and hypertension [3]. Thus, nephrotic syndrome during pregnancy is a condition that should be treated as soon as possible.

Nephrotic syndrome in pregnant women is rare, with an incidence of 0.012–0.025% [4]. MCNS is common in patients with primary nephrotic syndrome, occurring in 70–90% of children and 15% of adults [5]. However, only a few cases of MCNS during pregnancy have been reported previously. Therefore, there are no established management methods or treatment approaches. Of four previous case reports, two patients were diagnosed with MCNS by renal biopsy at less than 20 weeks of gestation [6, 7], and two patients were clinically diagnosed with MCNS because onset occurred after 30 weeks of gestation [8, 9]. Three cases were treated with corticosteroids, and all patients promptly remitted, with good outcomes for both mother and fetus.

Piccoli et al. conducted a systematic review of the risks of kidney biopsy when performed during pregnancy [10]. The incidence of complications during the entire period of pregnancy was higher than in the postpartum period (7% vs. 1%). Considering the gestation period, there was one case of macrohematuria and one case of hematoma not requiring blood transfusion with renal biopsy at 0–21 weeks of gestation. However, around 25 weeks, there were reports of major bleeding that resulted in preterm birth and fetal death, and serious complications were commonly observed. In other reports, all 11 patients who underwent renal biopsy at 9–27 weeks of gestation had no complications [11]. These results suggest that there is no increased risk of complications with renal biopsy in early pregnancy compared with non-pregnancy. Therefore, renal biopsy should be considered because treatment policy and renal prognosis are different depending on the type of nephritis. After 25 weeks of gestation, treatment approaches differ between glomerulonephritis and preeclampsia, and histological findings can greatly influence the course of treatment; however, risk and benefit should be fully considered in each case.

Corticosteroids are the main treatment for primary nephrotic syndrome. They are not teratogenic and can be used in pregnant women. In patients with MCNS, the remission rate with steroids is high, ranging from 80% to 90% in non-pregnant adults [5]. Although the remission rate in pregnant women is not known, past reports suggest that the rate is as high as in the general adult population. Therefore, steroids should be started as soon as MCNS is clinically diagnosed. In cases of steroid resistance, additional immunosuppressive agents may be considered. Cyclosporine may also be a treatment option for pregnant women.

Several adjunct medications are usually required for the treatment of the nephrotic syndrome. Pregnant women have a limited number of available treatment options, especially in the early stages of pregnancy during the organogenesis period. Methyldopa and hydralazine are the safest antihypertensive drugs, and nifedipine can be used after 20 weeks of gestation. Loop diuretics are available, paying attention to hemoconcentration and fetal electrolyte abnormalities. Prevention of gastrointestinal ulcers is essential, and H2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors can be used during pregnancy. Among the antithrombotic agents, only heparin and dipyridamole are available. Anticoagulants and clotting factor replacement therapy should be administered in severe cases of hypoalbuminemia or hypercoagulability, because clotting ability is increased, even during normal pregnancy.

Although the pathogenesis of MCNS is unclear, it has been suggested that it is associated with Ig E-related type I allergy. In fact, MCNS occurs more frequently in patients with a predisposition to allergy and higher levels of Ig E. Cytokines released from the activated T cells increase the permeability of the glomerular basement membrane and cause an impairment of the charge barrier [12]. In alopecia, on the other hand, T cells and mast cells infiltrate the periphery of the hair follicle and are considered to be an autoimmune disease of the hair follicle tissue. Alopecia is also associated with atopic disease and is particularly frequent when the disease is systemic or severe [13]. One case of MCNS and alopecia has been reported in the past, suggesting that mast cells may cause the enzymatic degradation of Ig E, which involved in glomerular basement membrane permeability, and that mast cells may be involved in the development of alopecia [14]. Although a direct causal relationship between the two has not been established, they may share the background of the mechanism of type I allergy even in our case.

In summary, we report a case of MCNS in a pregnant woman. The patient was successfully treated to remission using corticosteroids, and a healthy infant was delivered. Thus, early treatment initiation can provide a good prognosis for both mother and child.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Yokohama Foundation for Advancement of Medical Science; the Uehara Memorial Foundation; the Kanae Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science; the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, SENSHIN Medical Research; the MSD Life Science Foundation International; the Salt Science Research Foundation (18C4, 19C4, 20C4); The Cardiovascular Research Fund, Tokyo; the Strategic Research Project of Yokohama City University; the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED); and by The Translational Research program, Strategic PRomotion for practical application of INnovative medical Technology (TR-SPRINT) from AMED.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient in the case report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Morikawa M, Yamada T, Yamada T, Cho K, Yamada H, Sakuragi N, Minakami H. Pregnancy outcome of women who developed proteinuria in the absence of hypertension after mid-gestation. J Perinat Med. 2008;36(5):419–424. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Ma X, Zheng J, Liu X, Yan T. Pregnancy outcomes in patients with acute kidney injury during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1183-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Castro I, Easterling TR, Bansal N, Jefferson JA. Nephrotic syndrome in pregnancy poses risks with both maternal and fetal complications. Kidney Int. 2017;91(6):1464–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen AW, Burton HG. Nephrotic syndrome due to pre- eclamptic nephropathy in a hydatidiform mole and coexistent fetus. Obs Gynecol. 1979;53(1):130–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F. Minimal change disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):332–345. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05000516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lo JO, Kerns E, Rueda J, Marshall NE. Minimal change disease in pregnancy. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2014;27(12):1282–1284. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.852178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guru PK, Ramaeker DM, Jeybalan A, Shah NA, Bastacky S, Liang KV. Triple confusion: an interesting case of proteinuria in pregnancy. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27(5):1029–1032. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.190882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton P, Myers J, Gillham J, Ayers G, Brown N, Venning M. Urinary protein selectivity in nephrotic syndrome and pregnancy: resurrection of a biomarker when renal biopsy is contraindicated. Clin Kidney J. 2014;7(6):595–598. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfu103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato H, Asami Y, Shiro R, et al. Steroid pulse therapy for de novo minimal change disease during pregnancy. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:418–421. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.902910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piccoli GB, Daidola G, Attini R, et al. Kidney biopsy in pregnancy: evidence for counselling? A systematic narrative review. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;120(4):412–427. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen TK, Gelber AC, Witter FR, Petri M, Fine DM. Renal biopsy in the management of lupus nephritis during pregnancy. Lupus. 2015;24(2):147–154. doi: 10.1177/0961203314551812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maher A-H, Shimada M, Lee PY, et al. Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome and atopy: is there a common link. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:945–953. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohan GC, Silverberg JI. Association of vitiligo and alopecia areata with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:522–528. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura Y, Sugawara K, Tsuruta D. Case of alopecia universalis accompanied by minimal change nephrotic syndrome. J Dermatol. 2015;42:1131–1132. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]