Abstract

Background

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infection (BSI) management remains challenging for clinicians. Numerous in vitro studies report synergy when vancomycin (VAN) and daptomycin (DAP) are combined with beta-lactams (BLs), which has led to clinical implementation of these combinations. While shorter durations of bacteremia have often been reported, there has been no significant impact on mortality.

Methods

The Detroit Medical Center (DMC) developed and implemented a clinical pathway algorithm for MRSA BSI treatment in 2016 that included the early use of BL combination therapy with standard of care (VAN or DAP) and a mandatory Infectious Diseases consultation. This was a retrospective, quasi-experimental study at the DMC between 2013 and 2020. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the independent association between pathway implementation and 30-day mortality while adjusting for confounding variables.

Results

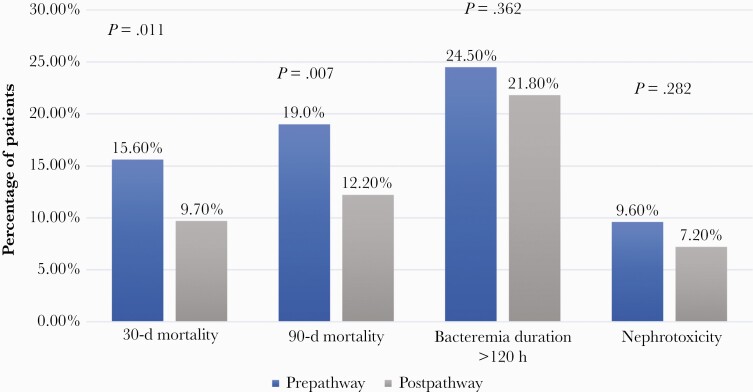

Overall, 813 adult patients treated for MRSA BSI were evaluated. Compared with prepathway (PRE) patients (n = 379), those treated postpathway (POST; n = 434) had a significant reduction in 30-day and 90-day mortality: 9.7% in POST vs 15.6% in PRE (P = .011) and 12.2% in POST vs 19.0% in PRE (P = .007), respectively.

The incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) was higher in the PRE compared with the POST group: 9.6% vs 7.2% (P = .282), respectively. After adjusting for confounding variables including Infectious Diseases consult, POST was independently associated with a reduction in 30-day mortality (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.608; 95% CI, 0.375–0.986).

Conclusions

Implementation of an MRSA BSI treatment pathway with early use of BL reduced mortality with no increased rate of AKI. Further prospective evaluation of this pathway approach is warranted.

Keywords: beta-lactams, bloodstream infections, combination therapy, gram-positive infections, MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections (BSIs) are associated with significant mortality, morbidity, and increased health care expenditures [1, 2]. Several strategies have been previously investigated by our group to improve patient outcomes in MRSA BSI [3–5]. Combination therapy (CT) with a beta-lactam (BL) in MRSA BSI has been proposed as a treatment strategy due to multiple reports demonstrating in vitro synergy between vancomycin (VAN)/daptomycin (DAP) and BLs [6–10]. To date, studies evaluating combination VAN/DAP with BLs have shown shorter days of bacteremia, lower hospital stays, and reduction in infection recurrence but not evidence of mortality benefit [11–16]. In most of these evaluations, the BL was typically an “add-on” as an escalation of therapy in refractory infections or as part of an empiric therapy where the BL was used as empiric therapy for gram-negative infections and not purposely for the treatment of MRSA. The only prospective trials that have evaluated BL CT were the Combination Antibiotics for Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CAMERA)–1 and CAMERA-2 studies and the pilot study of DAP plus ceftaroline vs VAN [17–19]. Both studies found shorter days of bacteremia but no difference in mortality. The CAMERA-2 study was prematurely stopped due to high rates of acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients receiving VAN and flucloxacillin or cloxacillin [18]. While cefazolin was 1 of the BL options, there were too few patients receiving these antibiotics to draw any reliable conclusions [18, 20]. The DAP plus ceftaroline study, albeit limited with a small sample size, found a significant survival benefit among patients receiving the combination vs those receiving VAN alone, which led to early termination of the trial [19].

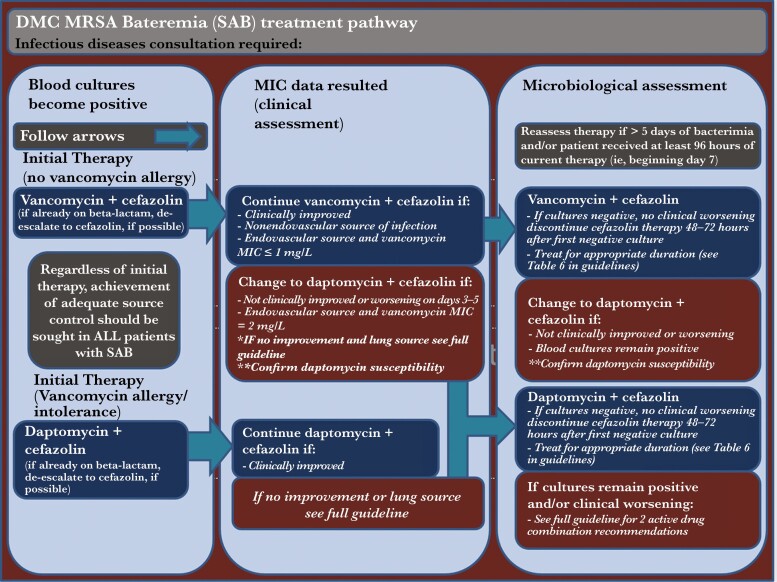

Based on the potential for improved outcomes with the use of BL CT, Infectious Diseases (ID) consultation, and microbiological assessment, a clinical pathway was developed at the Detroit Medical Center (DMC) with early use of BL CT as initial therapy for the treatment of MRSA bacteremia until at least 48 hours after blood culture sterilization (Figure 1) [21]. The primary BL was cefazolin; however, cefepime and other BL agents were allowed per patient specifics. Treatment modification may occur on days 3-5 of therapy and if necessary, followed by assessment on days 7–10. These were aimed to improve success rates with VAN or DAP, prevent the emergence of resistance, and reduce escalation to alternative, costlier, and more broad-spectrum agents [22]. The objective of this study was to evaluate the baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes of patients before and after the implementation of the MRSA BSI pathway at the DMC.

Figure 1.

Detroit Medical Center (DMC) Bacteremia Treatment Pathway.

METHODS

STUDY Design and Population

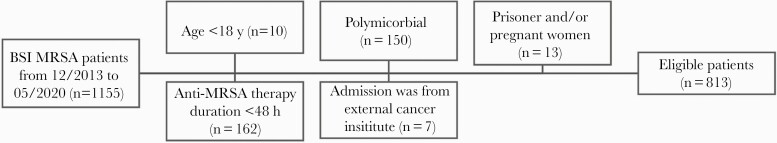

We conducted a retrospective, quasi-experimental study at the DMC between December, 2013, and June 2020. The DMC is a single large health care system that includes 8 hospitals within the greater Detroit area of Michigan. The DMC operates 8 hospitals and institutes, including the Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Detroit Receiving Hospital, Harper University Hospital, Huron Valley-Sinai Hospital, Hutzel Women’s Hospital, Rehabilitation Institute of Michigan, Sinai-Grace Hospital, and DMC Cardiovascular Institute. Patients were screened and included if they (1) were age ≥18 years and (2) had ≥1 MRSA-positive blood culture meeting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Criteria for BSI [23]. Exclusion criteria are illustrated in Figure 2. Patients were classified in the prepathway (PRE) group if they were admitted before the pathway implementation date (ie, on or after September 1, 2016) or in the postpathway (POST) group if admitted after the pathway implementation date. Only patients’ first encounter was collected, and repeat encounters were excluded. This study was reviewed and approved by the WSU Institutional Review Board and the DMC Research Review Committee.

Figure 2.

Patient screening, inclusion and exclusion. Abbreviations: BSI, bloodstream infection; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus..

Patient Consent

Patient consent was not required for this retrospective analysis.

Data Collection and Study Definitions

Patients’ data were derived from the electronic medical record and entered into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, Vanderbilt University). All blood cultures were processed at the DMC central microbiology laboratory according to standard procedures. MicroScan (Siemans Healthcare Diagnostics), Phoenix (BD) and Verigene (Luminex), and Etest (biomerieux) were utilized for antimicrobial susceptibility testing and/or bacterial identification depending on the time period. Variables associated with BSI were determined based on clinical notes and microbiological/diagnostic reports. The pathway is defined in detail in Figure 1, as well as in our institution’s portal [21]. Severity of illness and patient comorbidity were assessed using the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), respectively. Both were assessed at the time of index blood culture. Prolonged bacteremia was defined as lasting >120 hours [24]. Patients who died before clearing their bacteremia were excluded from the prolonged BSI analysis. In order to account for antibiotic adjustments during therapy, we describe several anti-MRSA/BL regimen scenarios in Table 2. Thirty-day and 90-day mortality were defined as death from any cause at 30 and 90 days, respectively. Sixty-day recurrence was defined as >1 MRSA-positive blood culture following clearance within 60 days of index blood culture collection. Safety outcomes are defined in Tables 1 and 3. Sources of bacteremia, occurrence of side effects, and other clinical variables were collected based on laboratory assessment and/or medical notes by the treating physician.

Table 2.

Treatment Characteristics of Patients Prepathway and Postpathway

| Prepathway (n = 379) | Postpathway (n = 434) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First pathway agenta | |||

| First MRSA agent | |||

| Vancomycin | 341 (90.0) | 416 (95.9) | .001 |

| Daptomycin | 27 (7.1) | 12 (2.8) | .004 |

| Ceftaroline | 9 (2.4) | 4 (0.9) | .099 |

| First BL regimen | |||

| None | 184 (48.5) | 18 (4.1) | <.001 |

| Cefepime | 79 (20.8) | 203 (46.8) | <.001 |

| Cefazolin | 22 (5.8) | 127 (29.3) | <.001 |

| Ceftaroline | 0 (0.0) | 10 (2.3) | .008 |

| Ceftriaxone | 29 (7.7) | 49 (11.3) | .098 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 37 (9.8) | 13 (3.0) | <.001 |

| Others | 28 (7.3) | 14 (3.2) | .551 |

| Time to start BL, hb,c | |||

| Cefepime | 1.9 (0.4–9.4) | 1.6 (0.3–17.5) | .873 |

| Cefazolin | 39.1 (27.4–64.2) | 39.4 (27.7–54.9) | .748 |

| Duration of BL, d | |||

| Cefepime | 1.2 (0.2–7.8) | 1.3 (0.5–3.0) | .932 |

| Cefazolin | 3.0 (3–6) | 4.3 (1.5–5.6) | .925 |

| Pathway agent at 48 hd | |||

| Anti-MRSA agent at 48 h | |||

| Vancomycin | 266 (70.2) | 372 (85.7) | <.001 |

| Daptomycin | 74 (19.5) | 43 (9.9) | <.001 |

| Ceftaroline | 20 (5.3) | 6 (1.4) | .002 |

| BL regimen at 48 h | |||

| Nonee | 240 (63.3) | 24 (8.5) | <.001 |

| Cefepime | 44 (11.6) | 88 (20.3) | <.001 |

| Cefazolin | 21 (5.5) | 193 (44.5) | <.001 |

| Ceftaroline | 0 (0) | 14 (3.2) | <.001 |

| Ceftriaxone | 24 (6.3) | 50 (11.5) | .010 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 24 (6.9) | 15 (3.5) | .027 |

| Others | 24 (6.3) | 5 (1.2) | <.001 |

| Primary pathway agentf | |||

| Primary anti-MRSA agent | |||

| Vancomycin | 201 (53.0) | 309 (71.2) | <.001 |

| Daptomycin | 131 (34.6) | 107 (24.7) | .002 |

| Ceftaroline | 45 (11.9) | 15 (3.5) | <.001 |

| Primary BL regimen | |||

| Cefepime | 62 (16.5) | 88 (20.3) | .551 |

| Cefazolin | 21 (5.5) | 242 (55.7) | <.001 |

| Ceftaroline | 1 (0.26) | 1 (0.23) | .565 |

| Ceftriaxone | 22 (5.8) | 27 (6.2) | .031 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 15 (3.9) | 6 (1.4) | <.001 |

| Others | 17 (8.7) | 27 (6.3) | .269 |

Values are presented as median (IQR) or No. (%).

Abbreviations: BL, beta-lactam; IQR, interquartile range; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

aFirst anti-MRSA agent or BL regimen was defined as the agent the patient received first during the encounter.

bIndicates from start of MRSA culture.

cIf regimen started before MRSA, time is considered 0.

dAnti-MRSA agent or BL regimen at 48 hours was defined as the agent/regimen received at 48 hours starting from the first anti-MRSA and/or BL.

eNone implies that after applying the 48-hour rule, no other beta-lactams were given (ie, beta-lactam duration was <48 hours.

fPrimary anti-MRSA agent or BL regimen was defined as the agent/regimen with the longest duration of treatment during the same encounter, only among those with a BL combination.

Table 1.

Bivariate Comparison of Baseline Demographics and Clinical Criteria Between Patients in Prepathway and Postpathway

| Criteria | Prepathway (n = 379) | Postpathway (n = 434) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 60 (50–71) | 59 (47–68) | .123 |

| Age ≥65 y | 146 (38.5) | 149 (34.3) | .215 |

| Race | .013 | ||

| African American | 293 (77.3) | 320 (74.8) | |

| Caucasian | 75 (19.8) | 81 (18.9) | |

| Others | 11 (2.9) | 33 (7.6) | |

| Weight, kg | 77.7 (64.3–96.0) | 76.8 (62.5–95.2) | .395 |

| BMI ≥30 | 136 (35.9) | 137 (31.7) | .210 |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| AKI | 105 (27.7) | 111 (25.6) | .493 |

| Cerebrovascular diseasea | 62 (16.4) | 63 (14.5) | .467 |

| Chronic pulmonary diseaseb | 110 (29.0) | 102 (23.5) | .074 |

| Moderate to severe or on chronic dialysis | 133 (35.1) | 129 (29.7) | .102 |

| Chronic dialysisc | 87 (23) | 101 (23.3) | .915 |

| Connective tissue diseased | 44 (11.6) | 31 (7.1) | .028 |

| Dementia | 38 (10.0) | 35 (8.1) | .329 |

| Diabetes, any | 169 (44.6) | 157 (36.2) | .015 |

| Without end organ damage | 55 (14.5) | 32 (7.4) | .001 |

| With end organ damage | 115 (30.3) | 125 (28.8) | .631 |

| Heart failure | 101 (26.6) | 85 (19.6) | .017 |

| Hemiplegia | 9 (2.4) | 7 (1.6) | .435 |

| Immunodeficiency, any | 28 (7.4) | 18 (4.1) | .046 |

| AIDS (CD4 <200) | 8 (2.1) | 10 (2.3) | .852 |

| HIV | 18 (4.7) | 15 (3.5) | .351 |

| Leukemia | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | .130 |

| Lymphoma | 3 (0.8) | 6 (1.4) | .422 |

| Tumor with metastasis | 15 (4.0) | 12 (2.8) | .344 |

| Tumor without metastasis | 11 (2.9) | 3 (0.7) | .016 |

| Liver disease, any | 56 (14.8) | 38 (8.8) | .007 |

| Milde | 45 (11.9) | 29 (6.7) | .010 |

| Moderate or severef | 11 (2.9) | 9 (2.1) | .447 |

| Myocardial infarction | 32 (8.4) | 30 (6.9) | .412 |

| No conditions | 14 (3.7) | 40 (9.2) | .002 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 4 (1.1) | 3 (0.7) | .572 |

| Peripheral vascular diseaseg | 56 (14.8) | 79 (18.2) | .190 |

| Prior hospitalization for ≥48 h in 90 d before index culture | 155 (40.9) | 126 (29.0) | <.0001 |

| Prior MRSA in 365 d preceding index culture | 46 (12.1) | 39 (9.0) | .143 |

| Prior MSSA in 365 d preceding index culture | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) | .766 |

| Prior surgery in 30 d preceding index culture | 22 (5.8) | 10 (2.3) | .010 |

| PWID | 56 (14.8) | 55 (12.7) | .384 |

| Sources of bacteremiah | |||

| Bone and joint | 59 (15.6) | 57 (13.1) | .322 |

| Endovascular | 4 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | .032 |

| Central nervous system abscess | 6 (1.6) | 2 (0.5) | .106 |

| Infective endocarditis | 59 (15.6) | 46 (10.6) | .035 |

| Intraabdominal | 6 (1.6) | 7 (1.6) | .973 |

| Intravenous catheter | 56 (14.8) | 78 (18.0) | .220 |

| Invasive prosthetic device | 16 (4.2) | 12 (2.8) | .256 |

| Other | 34 (9.0) | 47 (10.8) | .377 |

| Pneumonia | 95 (25.1) | 74 (17.1) | .005 |

| Skin and soft tissue | 99 (26.1) | 102 (23.5) | .388 |

| Urinary | 10 (2.6) | 16 (3.6) | .397 |

| Unknown | 31 (8.2) | 36 (8.3) | .952 |

| Vertebral abscess | 3 (0.8) | 6 (1.4) | .422 |

| Others factors | |||

| APACHE II | 17 (11–23) | 17 (11–22) | .415 |

| APACHE ≥30 | 50 (13.2) | 41 (9.6) | .103 |

| CCI | 3 (1–5) | 3 (1–4) | .005 |

| CCI ≥5 | 116 (30.6) | 110 (25.3) | .095 |

| Intensive care settingi | 73 (19.3) | 70 (16.3) | .266 |

| Infectious Diseases consult | 344 (90.8) | 410 (94.5) | .042 |

| Time to consult ID, h | 21.8 (4.4–39.2) | 13.3 (1.5–33.1) | .015 |

| Source control pursuedj | 371 (39.4) | 179 (43.7) | .223 |

| Automated VAN MIC testing performed | 370 (97.6) | 417 (96.1) | .212 |

| 0.5 | 7 (1.9) | 40 (9.6) | <.001 |

| 1 | 175 (47.3) | 368 (88.2) | <.001 |

| 2 | 188 (50.8) | 9 (2.2) | <.001 |

| VAN Etest performed | 100 (26.4) | 337 (77.6) | <.001 |

| 1 | 23 (23.0) | 76 (22.6) | .925 |

| 2 | 77 (77.0) | 261 (60.1) | .925 |

| AKIk | 28 (9.6) | 24 (7.2) | .282 |

| VAN TDM by AUCl | 65 (24.2) | 151 (47.2) | <.0001 |

| VAN AUC | 474.0 (401.3–550.8) | 461.2 (370.0–543.0) | .197 |

| On at least 1 nephrotoxic agentm | 70 (24.0) | 25 (7.5) | <.0001 |

| On VAN | 64 (21.9) | 24 (7.2) | <.0001 |

| Not on VAN | 44 (15.1) | 6 (1.8) | <.0001 |

| Other safety outcome | |||

| CPK increasen | 9 (2.4) | 1 (0.2) | .006 |

| Clostridium difficile | 16 (4.2) | 9 (2.1) | .077 |

Data presented as median (IQR) and/or No. (%), as appropriate.

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; BMI, body mass index; CCI, Carlson comorbidity index; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPK, creatinine phosphokinase; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; IQR, interquartile range; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; OA, osteoarthritis; PWID, person who injects drugs; Scr, serum creatinine; TDM, therapeutic drug monitoring; TIA, transient ischemic attack; VAN, vancomycin.

aStroke or TIA.

bAsthma or COPD.

cHemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

dOA or rheumatic arthritis.

eChronic hepatitis without cirrhosis.

fPortal hypertension or cirrhosis.

gDVT, chronic venous disease.

hSome patients may have had more than 1 source of infection.

iWhen obtaining index culture.

jIn PRE, intravenous catheter removal (n = 3), valvular replacement (n = 1), cardiac device removal (n = 2), incision and drainage (n = 5), debridement (n = 3). In POST, intravenous catheter removal (n = 45), valvular replacement (n = 3), cardiac device removal (n = 5), incision and drainage (n = 32), debridement (n = 20), amputation (n = 3), other (n = 16).

kAmong patients who did not have hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis (pre, n = 292, and post, n = 333). AKI was defined as an increase in Scr of ≥0.5 mg/dL or a ≥50% increase of Scr from baseline, whichever is greater, on 2 consecutive measurements from initial VAN dose until 72 hours after the last dose [13, 35].

lAmong the entire population of patients managed with vancomycin for ≥48 hours (pre, n = 269, and post, n = 320).

mThose include vancomycin. Most common nephrotoxic agent Among patients who were on VAN and in PRE, were diuretics (n = 27), followed by nonsteroidal anti-imflammatory drugs (n = 25). Among patients who were on VAN and in POST, most common agents were diuretics (n = 9), followed by vassopressors (n = 6). Among patients who are not on VAN and are in PRE, most common agents include diuretics (n = 15), followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (n = 21). While among patients who are not on VAN and in the POST, most common agents are angiotensin II converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (n = 2).

nIncreased CPK was defined as an increase of CPK to >600 U/L (if baseline <200 U/L) or >1000 U/L (if baseline >200 U/L) from initiation of drug to 72 hours after discontinuation of drug.

Table 3.

Bivariate Comparison of Baseline Demographics and Clinical Criteria Between Patients With 30-Day Mortality and Patients With No 30-Day Mortality

| Criteria | 30-Day Mortality (n = 101) | No 30-Day Mortality (n = 712) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 71 (62–80) | 59 (46–68) | .006 |

| Age ≥65 y | 71 (70.3) | 224 (31.5) | <.001 |

| Race | .365 | ||

| African American | 78 (78.0) | 535 (75.7) | .610 |

| Caucasian | 19 (19.0) | 137 (19.4) | .929 |

| Others | 4 (3.9) | 40 (5.6) | |

| BMI ≥30 | 30 (30.0) | 243 (34.2) | .408 |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| AKI | 41 (40.6) | 175 (24.6) | .001 |

| Cerebrovascular diseasea | 18 (17.8) | 107 (15.0) | .466 |

| Chronic pulmonary diseaseb | 36 (35.6) | 176 (24.7) | .019 |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||

| Moderate to severe chronic kidney disease or on chronic dialysis | 44 (43.6) | 218 (30.6) | .009 |

| Chronic dialysisc | 18 (17.8) | 170 (23.9) | .177 |

| Connective tissue diseased | 14 (13.9) | 61 (8.6) | .085 |

| Dementia | 18 (17.8) | 55 (7.7) | .001 |

| Diabetes disease, any | 35 (34.7) | 291 (40.9) | .233 |

| Without end organ damage | 5 (5.0) | 82 (11.5) | .046 |

| With end organ damage | 30 (29.7) | 210 (29.5) | .966 |

| Heart failure | 35 (34.7) | 151 (21.2) | .003 |

| Hemiplegia | 3 (3.0) | 13 (1.8) | .438 |

| Immunodeficiency, any | 9 (8.9) | 37 (5.2) | .131 |

| AIDS (CD4 <200) | 2 (2.0) | 16 (2.2) | .864 |

| HIV | 2 (2.0) | 31 (4.4) | .258 |

| Leukemia | 0 (0) | 2 (0.3) | .594 |

| Lymphoma | 2 (2.0) | 7 (1.0) | .370 |

| Tumor, any | 13 (12.9) | 28 (3.9) | <.001 |

| Without metastasis | 4 (4.0) | 10 (1.4) | .065 |

| With metastasis | 9 (8.9) | 18 (2.5) | .001 |

| Liver disease, any | 10 (9.9) | 84 (11.8) | .577 |

| Milde | 7 (6.9) | 67 (9.4) | .418 |

| Moderate or severef | 3 (3.0) | 17 (2.4) | .724 |

| Myocardial infarction | 16 (15.8) | 46 (6.5) | .001 |

| No conditions | 3 (3.0) | 51 (7.2) | .113 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 2 (2.0) | 5 (0.7) | .193 |

| Peripheral vascular diseaseg | 19 (18.8) | 116 (16.3) | .524 |

| Prior hospitalization for 48 h in 90 d before index culture | 43 (42.6) | 238 (33.4) | .070 |

| Prior MRSA in 365 d preceding index culture | 9 (8.9) | 76 (10.7) | .588 |

| Prior MSSA in 365 d preceding index culture | 0 (0) | 5 (0.7) | .398 |

| Prior surgery in 30 d preceding index culture | 3 (3.0) | 29 (4.1) | .594 |

| PWID | 4 (4.0) | 107 (15.0) | .002 |

| Sources of bacteremiah | |||

| Bone and joint | 1 (1.0) | 115 (16.2) | <.001 |

| Endovascular | 1 (1.0) | 3 (0.4) | .445 |

| Central nervous system abscess | 0 (0.0) | 8 (1.1) | .284 |

| Infective endocarditis | 11 (10.9) | 94 (13.2) | .517 |

| Intraabdominal | 1 (1.0) | 12 (1.7) | .602 |

| Intravenous catheter | 9 (8.9) | 125 (17.6) | .028 |

| Invasive prosthetic device | 3 (3.0) | 25 (3.5) | .780 |

| Other | 6 (5.9) | 75 (10.5) | .149 |

| Pneumonia | 41 (40.6) | 128 (18.0) | <.001 |

| Skin and soft tissue | 12 (11.9) | 189 (26.5) | <.001 |

| Urinary | 5 (5.0) | 21 (2.9) | .285 |

| Unknown | 15 (14.9) | 52 (7.3) | .010 |

| Vertebral abscess | 1 (1.0) | 8 (1.1) | .904 |

| Others factors | |||

| APACHE II | 24 (18–31) | 16 (10–22) | <.001 |

| APACHE ≥30 | 33 (33.0) | 58 (8.2) | <.001 |

| CCI | 4 (2–6) | 3 (1–5) | <.001 |

| CCI ≥5 | 47 (46.5) | 179 (25.1) | <.001 |

| Intensive care settingi | 32 (32.3) | 111 (15.7) | <.001 |

| Infectious Diseases consult | 87 (86.1) | 667 (93.7) | .006 |

| Source controlj | 19 (19.6) | 306 (44.7) | <.001 |

| Automated VAN MIC testing performed | 98 (97.0) | 689 (96.8) | .889 |

| 0.5 | 8 (8.2) | 39 (5.7) | .328 |

| 1 | 62 (63.3) | 481 (69.8) | .190 |

| 2 | 28 (28.6) | 169 (24.5) | .387 |

| VAN Etest performed | 49 (48.5) | 388 (54.5) | .613 |

| 1 | 86 (22.2) | 13 (26.5) | .492 |

| 2 | 36 (73.5) | 302 (77.8) | .492 |

| AKIk | 21 (25.3) | 31 (5.7) | <.001 |

| VAN TDM by AUCl | 14 (17.7) | 202 (39.6) | <.001 |

| VAN AUC | 517.5 (358.5–555.4) | 463.0 (380.0–543.4) | .642 |

| On at least 1 nephrotoxic agentm | 18 (21.7) | 77 (14.2) | .077 |

| On VAN | 18 (21.7) | 70 (12.9) | .032 |

| Not on VAN | 5 (6.0) | 45 (8.3) | .476 |

| Other safety outcome | |||

| CPK increasen | 1 (1.0) | 9 (1.3) | .815 |

| Clostridium difficile | 7 (6.9) | 18 (2.5) | .016 |

Data are presented as median (IQR) and/or No. (%).

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; BMI, body mass index; CCI, Carlson comorbidity index; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPK, creatinine phosphokinase; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; IQR, interquartile range; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; OA, osteoarthritis; PWID, person who injects drugs; Scr, serum creatinine; TDM, therapeutic drug monitoring; TIA, transient ischemic attack; VAN, vancomycin.

aStroke or TIA.

bAsthma or COPD.

cHemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

dOA or rheumatic arthritis.

eChronic hepatitis without cirrhosis.

fPortal hypertension or cirrhosis.

gDVT, chronic venous disease.

hSome patients may have had more than 1 source of infection.

iWhen obtaining index culture.

jIn 30-day mortality, intravenous catheter removal (n = 3), incision and drainage (n = 1), debridement (n = 2). In patients with no 30-day mortality, intravenous catheter removal (n = 45), valvular replacement (n = 4), cardiac device removal (n = 7), incision and drainage (n = 36), debridement (n = 21), amputation (n = 3), other (n = 16).

kAmong patients who did not have hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis (30-day mortality, n = 83, and no 30-day mortality, n = 542). AKI was defined as an increase in serum creatinine (Scr) of ≥0.5 mg/dL or a ≥50% increase of Scr from baseline, whichever is greater, on 2 consecutive measurements from initial VAN dose until 72 hours after the last dose [13, 35].

lAmong the entire population of patients managed with vancomycin for ≥48 hours (30-day mortality, n = 79, and no 30-day mortality, n = 510).

mMost common nephrotoxic agents among patients who were on VAN and in 30-day mortality group were diuretics (n = 11), followed by piperacillin-tazobactam and contrast media (n = 5, each). Among patients who were on VAN and were not in 30-day mortality group, most common were diuretics (n = 25), followed by piperacillin-tazobactam and contrast media (n = 5, each). Among patients who are not on VAN and experienced 30-day mortality group, most common were diuretics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and diuretics (n = 2, each). While among patients who are not on VAN and did not experience 30-day mortality, most were nephrotoxic agents are diuretics (n = 11), followed by angiotensin II converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (n = 3).

nIncreased CPK was defined as increase of CPK to >600 U/L (if baseline <200 U/L) or >1000 U/L (if baseline >200 U/L) from initiation of drug to 72 hours after discontinuation of drug.

Outcome

The primary outcome was 30-day mortality. Secondary end points included 90-day mortality, 60-day recurrence, prolonged bacteremia, duration of bacteremia, hospital length of stay, ID consult, and AKI. All clinical outcome time points were measured from index blood culture collection.

Statstical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate patients’ demographics. Nominal data were reported as counts and percentages, and continous data were reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical variables were compared by the chi-square test, and continuous variables were compared by the Mann-Whitney U test. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the independent association between POST and 30-day mortality while adjusting for confounding variables. Data from POST, along with all variables associated with 30-day mortality in the bivariate analysis at a P value <.2, were entered into the model simultaneously and removed using a backward stepwise approach. Covariates were retained in the model if the P value for the likelihood ratio test for their removal was <.1. The variance inflation factor was used to assess the multicollinearity of covariates in the model, with values in the range of 1–5 considered acceptable. When certain variables were colinear, the variable with the highest number of patients was retained. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to assess the model’s fit. All tests were 2-tailed, with P values <.05 considered statistically significant. If a patient died due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in POST, that patient was excluded from the regression analysis.

To account for inherent changes over the study time period such as in medical practice, strain epidemiology, and patient mix that may have influenced clinical outcomes, we performed an interrupted time series analysis. We examined changes over time as well as differential changes over time in the PRE and POST periods. Also, within the POST group, classification and regression tree (CART) analysis was performed to determine the time to start BL most predicitve of 30-day mortality. To assess the independent association between time to BL dichotomized at the CART-derived cut-point and 30-day mortality, a multivariable logistic regression model was performed. Additionally, we also repeated the multivariable logistic regression analysis using 90-day mortality as an outcome. IBM SPSS software, version 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), was used for all calculations.

RESULTS

Overall, 1155 BSI patients were evaluated, and 342 were excluded. A total of 813 adult patients treated for MRSA BSI were evaluated (PRE, n = 379, and POST, n = 434) (Figure 2). The entire cohort was predominately male (75.4%), with a median (IQR) age of 50.5 (39.6–61.2) years. The median (IQR) APACHE II and CCI were 17 (11–23) and 3 (1–5), respectively. A comparison of baseline characteristics between PRE and POST is provided in (Table 1). Some notable differences were observed between the 2 groups. Diabetes was more prominent in the PRE compared with the POST group: 44.6% vs 36.2% (P = .015); as well as heart failure: 26.6% vs 19.6% (P = .017); and previous hospitalization: 40.9% vs 29.0% (P < .0001). Conversely, lack of comorbid conditions was less common in PRE compared with POST: 3.7% vs 9.2%, respectively (P = .002). Vancomycin susceptibilities over the 2 study periods are displayed in Table 1. The criteria of anti-MRSA agents and BL regimens in the PRE and POST groups are illustrated in Table 2. The most common first anti-MRSA agent is VAN in both PRE and POST: 90.0% and 95.9%, respectively (P = .001). Lack of BL CT (ie, monotherapy [MT]) was most common in PRE, 48.5%, while the most common first BL agent was cefepime in POST, 46.8%. The most common anti-MRSA agent at 48 hours was VAN in both PRE and POST: 70.2% and 85.7%, respectively (P < .001). Lack of BL combination was common in PRE, 63.3%, while the most common BL agent at 48 hours was cefazolin, 44.5%, in POST. The most common primary anti-MRSA agent was VAN in both PRE and POST: 53.0% and 71.2%, respectively (P < .001). Among patients who had a BL, the most common primary BL agent was cefepime in PRE, 16.5%, and cefazolin, 55.7%, in POST.

Thirty-day and 90-day mortality were higher in PRE compared with POST, 15.6% vs 9.7% (P = .011) and 19.0% vs 12.2% (P = .007), respectively (Figure 3). Sixty-day recurrence was comparable between PRE and POST: 5.8% and 4.3%, respectively (P = .978). In PRE, 24.5% of patients experienced prolonged bacteremia, compared with 21.8% in the POST group (P = .362). Regarding bacteremia duration, the mean (SD) was 4.2 (4.2) vs 3.6 (2.6) days in the PRE and POST groups, respectively (P < .001). The vast majority of patients had an ID consult, 92.7%, which was more common in POST compared with PRE: 94.5% and 90.8%, respectively (P = .042). The median (IQR) hospital length of stay was similar in the POST group compared with the PRE group: 11 (8–19) and 12 (8–19) days, respectively (P = .486). The incidence of AKI in the entire cohort was 8.3% and was higher in the PRE compared with the POST group: 9.6% and 7.2%, respectively, but was not statistically significant (P = .282). With CART analysis for the time to start a BL, none of the cutoff points identified by CART were predictive of the primary end point in the entire cohort.

Figure 3.

Clinical outcomes of patients in the PRE and POST groups.

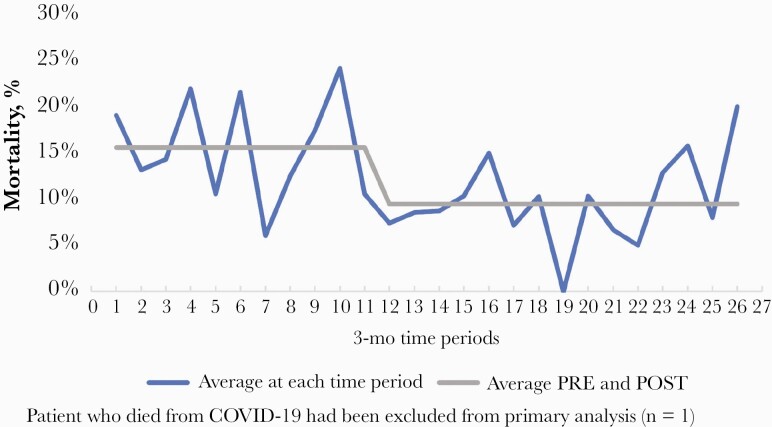

A bivariate comparison of baseline criteria between patients with and without 30-day mortality is presented in Table 3. Notable differences between the 2 groups at the prespecified P value were included in the multivariable logistic regression model (Supplementary Table 1). Based on the final variables retained in the model, the pathway was independently associated with a reduction in 30-day mortality (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.608; 95% CI, 0.375–0.986). Other variables independently associated with 30-day mortality are listed in Table 4. In the interrupted time series analysis when differential changes over time in the PRE and POST periods were examined for 30-day mortality as well as overall changes over time, the effect of time was not statistically significant (P = .710 and P = .404, respectively) (Figure 4). This indicates that 30-day mortality was not changing as a function of time and that the improvement in survival was due to POST intervention (Supplementary Figure 1). Additionally, when ID consult was excluded as a study variable and was considered as a component of POST in the logistic regression model, the primary analysis results remained consistent. Moreover, when the model was performed using 90-day mortality as the outcome with the same variable for the primary analysis, treatment within the pathway was also independently associated with reduced odds of 90-day mortality (aOR 0.634; 95% CI, 0.412–0.977). The Hosmer and Lemeshow test demonstrated an acceptable P value (P = .788).

Table 4.

Multivariable Logistic Regression for Factors Independently Associated With 30-Day Mortality

| Variable | OR | P Value | 95% CI | aOR | P Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POST | 0.681 | .140 | 0.409–1.134 | 0.608 | .044 | 0.375–0.986 |

| Age ≥65 y | 3.156 | <.001 | 1.827–5.454 | 3.314 | <.001 | 2.003–5.483 |

| APACHE II score | 1.075 | <.001 | 1.041–1.111 | 1.084 | <.001 | 1.053–1.115 |

| Diabetes with no end organ damage | 0.280 | .017 | 0.98–0.798 | 0.257 | .009 | 0.092–0.714 |

| PWID | 0.419 | .138 | 0.133–1.323 | 0.385 | .092 | 0.127–1.170 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2.257 | .036 | 1.053–4.837 | 2.214 | .030 | 1.080–4.535 |

| Source of bacteremia, other | 0.408 | .082 | 0.148–1.120 | 0.428 | .073 | 0.169–1.082 |

| Source of bacteremia, intravenous catheter | 0.244 | .004 | 0.093–0.638 | 0.248 | <.001 | 0.115–0.536 |

| Source of bacteremia, skin and soft tissue | 0.118 | .527 | 0.235–1.178 | 0.552 | .096 | 0.274–1.111 |

| Source of bacteremia, bone and joint | 0.071 | .012 | 0.009–0.4564 | 0.077 | .013 | 0.010–0.581 |

Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test P = .192; variance inflation factor 1–5 for all variables included at model entry. One patient was excluded from the analysis due to coronavirus disease 2019 (n =1).

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; OR, odds ratio; PWID, person who injects drugs; POST, postpathway.

Variables included in the model include (1) acute kidney injury, (2) age ≥65 years, (3) any immune-deficiency condition, (4) APACHE II, (5) CCI, (6) chronic pulmonary disease, (7) Infectious Diseases consult, (8) intensive care admission upon index culture, (9) dementia, (10) diabetes without end organ damage, (11) heart failure, (12) moderate to severe chronic kidney disease or on chronic dialysis, (13) myocardial infarction, (14) no comorbid medical conditions, (15) peptic ulcer disease, (16) prior hospitalization for 48 hours in 90 days before index culture, (17) postpathway, (18) source control, (19) source is bone and joint, (20) source is intravenous catheter, (21) source is other site, (22) source is pneumonia, (23) source is skin and soft tissue infection, (24) source is unknown.

Figure 4.

Time series analysis of patients in PRE compared to POST.

DISCUSSION

As opposed to previous evaluations of BL CT, we initiated a formalized clinical pathway for the treatment of MRSA BSI. The pathway required early BL CT as a key component in addition to a mandatory ID consult, microbiological evaluation, and prespecified timely therapy assessments. Our study demonstrated a significant difference in both 30-day and 90-day mortality even after adjusting for confounding variables, including ID consultation. There are important differences worth highlighting from previous evaluations of BL combination. First the BL was initiated early in the treatment course as a function of the clinical pathway. Because early use of BL (ie, within 48 hours) was established in most patients (370, 88.9%), we were unable to determine a specific time to start BL that was most predictive of outcomes. This may have contributed to the improved mortality observed in our study. This was in contrast to CAMERA-2, where the average time to randomization was 48 hours [18]. This ultimately caused the majority of the MT arm to receive therapy within 72 hours of randomization, thus potentially misclassifying the MT arm toward the null. In addition, many of the CT patients did not receive any BL until 72 hours into their BSI culture, exceeding the window during which benefit is highly projected. Additionally, while ID consult is a known contributor to improved outcomes in MRSA BSI patients, we controlled for this factor to demonstrate that it was not the primary driver of the mortality benefit [25, 26].

Of interest, while we demonstrated that fewer patients experienced persistent bacteremia in the POST compared with the PRE group, this was not statistically significant. However, there was a statistically significant decrease in bacteremia duration, 4.2 vs 3.6 days in the PRE compared with the POST group, respectively. Although not all reports have not been able to demonstrate such an improvement, most studies demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in bacteremia by 1–2 days [11, 13–15, 17–19]. It is important to note that persistent bacteremia has been correlated with but not validated as a marker for mortality [27, 28].

Although there have been a few differences in underlying comorbid conditions between the PRE and POST groups, these factors did not play an impactful role on mortality as observed in our regression model. In addition, the clinical microbiology laboratory has used both the MicroScan (primarily PRE) and Phoenix (primarily POST) automated susceptibility platforms over the course of 9 years. MicroScan has been shown to be more likely to overcall an MIC value of 2 mg/L, whereas Phoenix tends to undercall an MIC of 2 mg/L [29, 30]. Therefore, it was not surprising to find more MIC values of 2 mg/L reported in PRE compared with POST, as Microscan was utilized in this time period. In addition, some isolates were also tested by Etest, which also by virtue of differences in inoculum tends to read higher than automated testing or the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) microdilution method. Of interest, our laboratory at Wayne State University frequently peforms vancomycin MICs for various research purposes using the “gold standard” broth microdilution technique on MRSA bloodstream ioslates from the Detroit Medical Center. We went back and were able to match 414 BSI isolates that were from patients in the PRE (110/379) and POST (314/434) time periods. In the PRE period, 90% of the VAN MICs were 1 or less, and in the POST period 95% were 1 mg/L or less. Therefore, there does not seem to be any major difference in vancomycin susceptibility between the 2 time periods. Overall, because of the inability to correctly identify VAN MIC of 1 mg/L and 2 mg/L in the entire cohort of patients, the exact impact of the VAN MIC on clinical outcome is unclear in this analysis.

AKI was relatively low in our cohort, even when BLs were combined with VAN. First, it is important to note that CAMERA-1 and CAMERA-2 used flucloxacillin, a semisynthetic penicillin associated with significant nephrotoxicity risks for the majority of the patients [17, 18]. In a secondary nephrotoxicity analysis of the CAMERA-2, AKI was independently more common in the flucloxacillin/VAN group but not the cefazolin/VAN group [31]. In our clinical pathway, cefepime (n = 282, 34.6%) and cefazolin (n = 149, 34.6%) were the most common BLs used in POST, suggesting that cephalosporin-based regimens appear to be safer when combined with VAN than penicillin-based regimens. A recent meta-analysis of CT studies also suggested that there is no difference in AKI between CT and MT, and notably most of the included studies had a cephalosporin-based BL [16]. Second, VAN AUC-guided dosing, which is associated with lower AKI, was implemented at the DMC in 2015 and is consequently more prevalent in POST compared with PRE [32, 33]. Third, our institution switched from piperacillin/tazobactam to cefepime as the primary empiric gram-negative agent of choice in 2015. As evident from the results, piperacillin/tazobactam was more prominent in PRE compared with POST (P < .001). Lastly, there was a lower proportion of patients on nephrotoxins in POST compared with PRE (P < .0001) [34]. Collectively, it is possible that the combination of these factors contributed to the lower incidence of AKI in POST, which has been previously demonstrated in studies conducted at our health care center [32, 35, 36].

Fewer patients were on DAP or ceftaroline as the primary anti-MRSA agent in POST compared with PRE: 24.7% vs 34.6% and 3.5% vs 11.9%, respectively. This demonstrates that we were able to improve success rates with VAN and decrease the use of costlier and more broad-spectrum agents.

Our study differs from previous evaluations of CT for the treatment of MRSA BSI as it is a real-world extensive evaluation of how a comprehensive pathway that incorporates diagnostics, timely ID consult, and systematic early utilization of CT can improve patient outcomes. While cefazolin is the mainstay of BL choice in the pathway, other BLs were also acceptable to pair with the anti-MRSA agent. We previously demonstrated that cefepime can positively impact patients’ outcomes in MRSA BSIs [13]. In order to account for a possible selection bias in patients with concomitant MRSA and gram-negative infection who had a higher anticipated mortality risk, we excluded those with polymicrobial bacteremia. Therefore, the impact of empiric cefepime as opposed to targeted BL agents was minimal. Additionally, because the study had a large sample size, particularly for a real-world analysis, we were able to detect and thus adjust for various confounding variables that may have contributed to positive clinical outcomes. To ensure that the results were not biased by PRE and POST variable imbalances, we repeated the logistic regression analysis with selected high-risk groups. In addition, we performed an inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) analysis. The results of both of these analyses remained consistent with the primary findings and were statistically significant (Supplementary Table 2).

This study is not without limitations. First, this was a retrospective study and was challenged by inherent limitations of the design. Second, despite this being a multicenter study, it was limited to hospitals within a single health care system, and the results may not be generalizable to other patient populations. Additionally, because the time frame of the study was over 9 years, it may be possible that improvements in medical practices have contributed to patient outcomes as well as changes in strain epidemiology and virulence. However, we attempted to control for this by performing additional analyses using time in the study period as a variable, and the results remained consistent. Notably, we did find an increase in excess mortality during the last 4 months of our study period (ie, March to June of 2020), which may be related to the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the state of Michigan [37, 38]. Additionally, although we observed an improvement in 90-day mortality, this was likely impacted by improvement in 30-day mortality. Lastly, although our clinical pathway was reliant on CT with BLs, the impact of the pathway as an entire process might have been the driver of mortality rather than BL CT alone, and thus might explain the mortality benefit observed in our study but not in previous studies.

In conclusion, we have shown that a comprehensive clinical pathway to manage MRSA BSI can have a positive impact on patient outcomes, particularly improved survival. We demonstrated that the selection of the BL, such as cefazolin or cefepime, for CT is important as our results show that CT was safe and not associated with increased incidence of AKI. Lastly, while multiple anti-MRSA agents and BL were included in the clinical pathway, the predominant regimens were VAN/cefazolin and VAN/cefepime. Therefore, it would be of interest for future studies including prospective evaluations to be directed on evaluating anti-MRSA agents other than VAN in CT with these BLs.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Financial support. No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or for publication of this article.

Potential conflicts of interest. S.A., A.M.F., E.Z., T.M., S.H., J.J.Z., J.J., R.M., J.M.P., S.D., M.R.S., T.T., T.C., and N.R. have nothing to disclose; S.C.J.J. has received honoraria for speaking from Melinta and Sunovion; M.J.R.: research support, consultant or speaker for Allergan, Contrafect, Melinta, Merck, Motif, Paratek, Tetraphase, Shionogi, and Spero, and is partially supported by NIAID AI121400 and AI1300056-04.

Prior presentations. Data from a proportion of patients in this analysis were been presented, in part, at the American Society for Microbiology (ASM); October 3–7, 2018; San Francisco, CA (abstract 2379); at the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Meeting; October 2–6, 2019; Washington, DC (abstract 2250); and in the following publications: Alosaimy et al., Jorgensen et al., and Zasowski et al. [11–13].

References

- 1. van Hal SJ, Jensen SO, Vaska VL, et al. Predictors of mortality in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012; 25:362–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang FD, Chen YY, Chen TL, Liu CY. Risk factors and mortality in patients with nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Am J Infect Control 2008; 36:118–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murray KP, Zhao JJ, Davis SL, et al. Early use of daptomycin versus vancomycin for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia with vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration >1 mg/L: a matched cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56:1562–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Claeys KC, Zasowski EJ, Casapao AM, et al. Daptomycin improves outcomes regardless of vancomycin MIC in a propensity-matched analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:5841–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kullar R, Davis SL, Kaye KS, et al. Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship pathway with daptomycin for optimal treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Pharmacotherapy 2013; 33:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Climo MW, Patron RL, Archer GL. Combinations of vancomycin and beta-lactams are synergistic against staphylococci with reduced susceptibilities to vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999; 43:1747–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leonard SN. Synergy between vancomycin and nafcillin against Staphylococcus aureus in an in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. PLoS One 2012; 7:e42103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hagihara M, Wiskirchen DE, Kuti JL, Nicolau DP. In vitro pharmacodynamics of vancomycin and cefazolin alone and in combination against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:202–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tran KN, Rybak MJ. β-lactam combinations with vancomycin show synergistic activity against vancomycin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA), and heterogeneous VISA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62:e00157-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dilworth TJ, Leonard SN, Vilay AM, Mercier RC. Vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus in an in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Clin Ther 2014; 36:1334–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alosaimy S, Sabagha NL, Lagnf AM, et al. Monotherapy with vancomycin or daptomycin versus combination therapy with β-lactams in the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: a retrospective cohort analysis. Infect Dis Ther 2020; 9:325–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jorgensen SCJ, Zasowski EJ, Trinh TD, et al. Daptomycin plus β-lactam combination therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: a retrospective, comparative cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zasowski EJ, Trinh TD, Atwan SM, et al. The impact of concomitant empiric cefepime on patient outcomes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections treated with vancomycin. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:XXX–XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Casapao AM, Jacobs DM, Bowers DR, et al. ; REACH-ID Study Group . Early administration of adjuvant β-lactam therapy in combination with vancomycin among patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection: a retrospective, multicenter analysis. Pharmacotherapy 2017; 37:1347–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCreary EK, Kullar R, Geriak M, et al. Multicenter cohort of patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia receiving daptomycin plus ceftaroline compared with other MRSA treatments. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7:XXX–XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kale-Pradhan PB, Giuliano C, Jongekrijg A, Rybak MJ. Combination of vancomycin or daptomycin and beta-lactam antibiotics: a meta-analysis. Pharmacotherapy 2020; 40:648–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davis JS, Sud A, O’Sullivan MVN, et al. Combination of vancomycin and β-lactam therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a pilot multicenter randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tong SYC, Lye DC, Yahav D, et al. ; Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases Clinical Research Network . Effect of vancomycin or daptomycin with vs without an antistaphylococcal β-lactam on mortality, bacteremia, relapse, or treatment failure in patients with MRSA bacteremia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 323:527–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Geriak M, Haddad F, Rizvi K, et al. Clinical data on daptomycin plus ceftaroline versus standard of care monotherapy in the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63:e02483-18 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gandhi TN, Malani PN. Combination therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: not ready for prime time. JAMA 2020; 323:515–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Detroit Medical Center. Guidelines for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. 2021. https://www.dropbox.com/s/djhp7amff4gc2uk/S%20aureus%20bacteremia%20pathway.pdf?dl=0. Accessed March 2021.

- 22. Hornak JP, Anjum S, Reynoso D. Adjunctive ceftaroline in combination with daptomycin or vancomycin for complicated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia after monotherapy failure. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2019; 6:2049936119886504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 2008; 36:309–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zacharioudakis IM, Zervou FN. Is early clearance of blood cultures the be-all and end-all outcome? Clin Infect Dis. 2021; 72:179–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Paulsen J, Solligård E, Damås JK, et al. The impact of infectious disease specialist consultation for Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: a systematic review. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3:XXX–XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chesdachai S, Kline S, Helmin D, Rajasingham R. The effect of infectious diseases consultation on mortality in hospitalized patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Candida, and Pseudomonas bloodstream infections. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7:XXX–XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rose WE, Eickhoff JC, Shukla SK, et al. Elevated serum interleukin-10 at time of hospital admission is predictive of mortality in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:1604–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hawkins C, Huang J, Jin N, et al. Persistent Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: an analysis of risk factors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:1861–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rybak MJ, Vidaillac C, Sader HS, et al. Evaluation of vancomycin susceptibility testing for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: comparison of Etest and three automated testing methods. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51:2077–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Revolinski SL, Doern CD. Point-counterpoint: should clinical microbiology laboratories report vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentrations? J Clin Microbiol. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu J, Tong SYC, Davis JS, et al. ; CAMERA2 Study Group . Vancomycin exposure and acute kidney injury outcome: a snapshot from the CAMERA2 study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7:XXX–XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: a revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2020; 77:835–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lodise TP, Drusano G. Vancomycin area under the curve-guided dosing and monitoring for adult and pediatric patients with suspected or documented serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: putting the safety of our patients first. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72:1497–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Naughton CA. Drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Am Fam Physician 2008; 78:743–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Finch NA, Zasowski EJ, Murray KP, et al. A quasi-experiment to study the impact of vancomycin area under the concentration-time curve-guided dosing on vancomycin-associated nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61:e01293-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Navalkele B, Pogue JM, Karino S, et al. Risk of acute kidney injury in patients on concomitant vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam compared to those on vancomycin and cefepime. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT, et al. Excess Deaths From COVID-19 and Other Causes, March-July 2020. JAMA 2020; 324:1562–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Weekly counts of deaths by state and select causes. 2020. Available at: https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Weekly-Provisional-Counts-of-Deaths-by-State-and-S/muzy-jte6.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.