Dear editor,

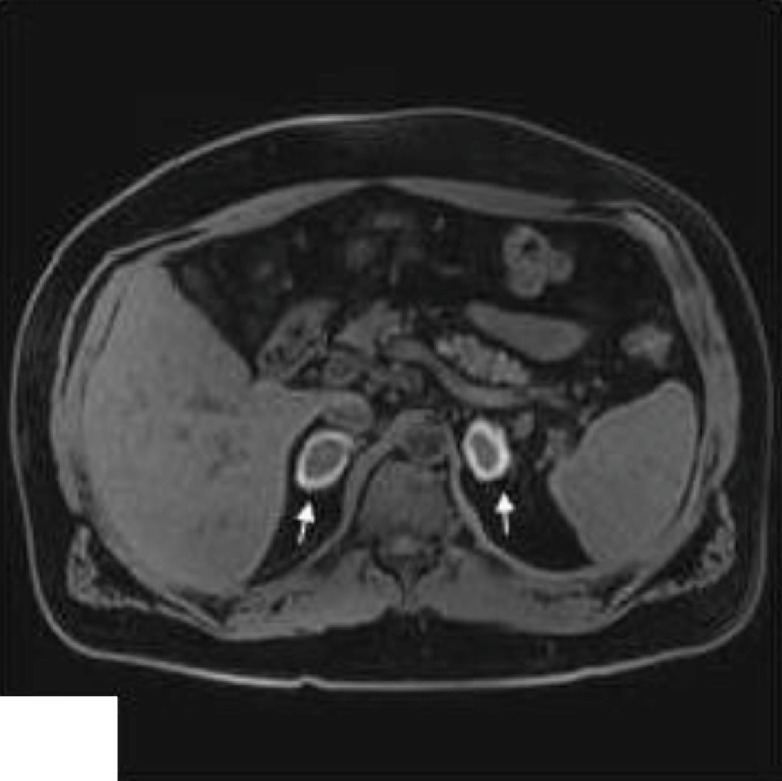

In the setting of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination a very uncommon cause for adrenal insufficiency was observed in a 47-year-old man without previous relevant disease who was admitted for bilateral segmentary pulmonary embolism (without hemodynamic compromise) 10 days after receiving adenoviral (ChAdOx1) vector-based COVID-19 vaccine. Therapy with low-molecular-weight-heparin (LMWH) was initiated and 24 h later the patient began to develop neurological symptoms (headache, somnolence, and mild confusion). Physical examination showed normal vital signs (blood pressure: 139/93 mmHg, pulse-oxygen saturation: 96%, afebrile), slow mental activity, negative meningeal signs, and absence of focal neurological deficit. Laboratory tests showed a substantial increase in d-dimer (20,506 ng/ml) and thrombocytopenia (51,000/μl; previous: 103,000/μl) as main findings. In cranial CT/MRI, findings of cerebral venous thrombosis were detected in several locations (Fig. 1a and 1b ). With clinical diagnosis of vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT), LMWH was discontinued and treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins and subcutaneous fondaparinux was started. Platelet-factor-4 (PF4) antibody testing was positive. Ten days later, the patient had a completely normal level of consciousness and mental status, and control cranial MRI was performed (Fig. 2 ), showing partial revascularization of the superior sagittal cerebral venous sinus. However, he started to develop arterial hypotensive tendency and progressive abdominal discomfort. Mild hyponatremia was detected (natraemia:130 mmol/L; previous levels: 138–140 mmol/L). Abdominal MR image showed bilateral adrenal nodular enlargement with hyperintense peripheral halo and hypointense center, corresponding to ongoing subacute bilateral adrenal hemorrhage (Fig. 3 ). In hormonal laboratory testing, low levels of cortisol (3.8μg/dL; range values:4.8–19.5), DHEA (0.3 ng/mL;1.1–10.6 ng/mL) and aldosterone (42.2pg/mL;70–300), and high ACTH levels (345 pg/mL;7–63) confirmed primary adrenal insufficiency. Hormone replacement therapy with hydrocortisone was started, achieving disappearance of abdominal pain and rapid normalization of natraemia levels. Finally, the patient was discharged with the diagnosis of non-massive pulmonary embolism, cerebral venous thrombosis and primary adrenal insufficiency due to bilateral adrenal hemorrhage in the setting of vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT).

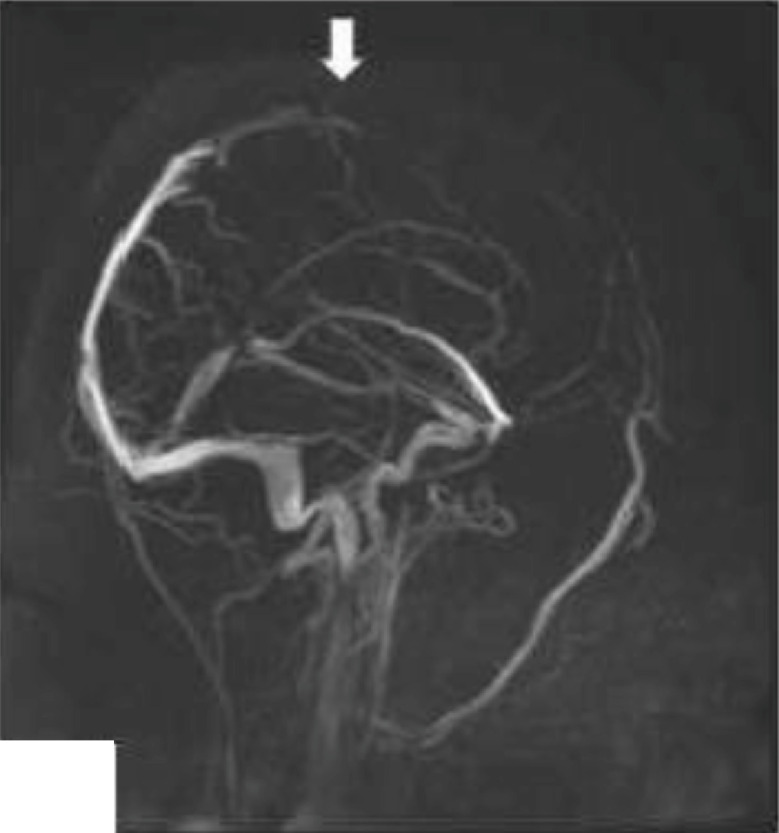

Fig. 1a.

Superior longitudinal cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (arrow).

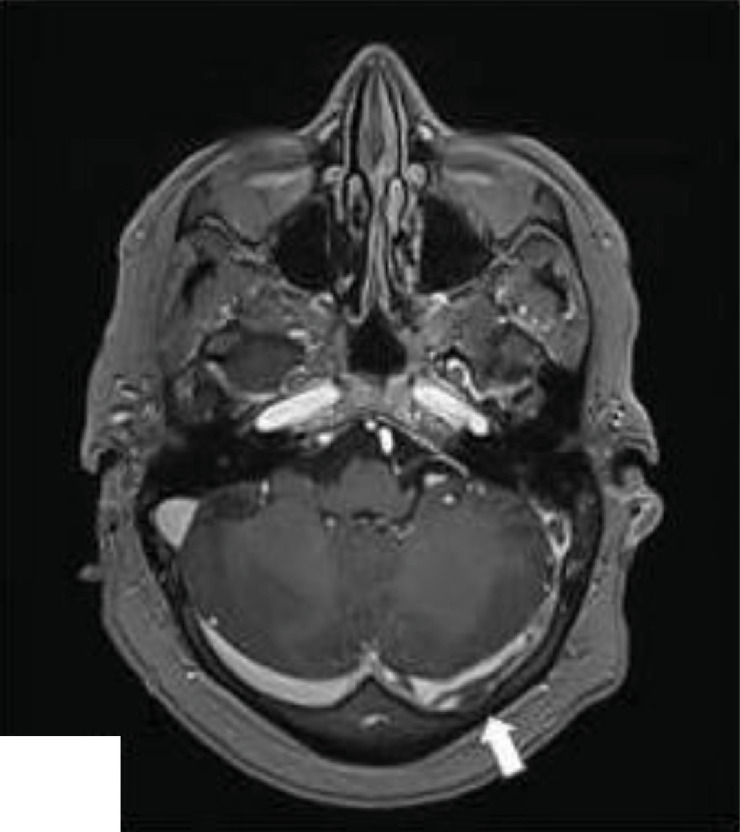

Fig. 1b.

Left sigmoid cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (arrow).

Fig. 2.

Partial revascularization of the superior sagittal cerebral venous sinus (arrow).

Fig. 3.

Bilateral adrenal nodular enlargement with hyperintense peripheral halo and hypointense center, corresponding to ongoing subacute bilateral adrenal hemorrhage (arrows).

Adrenal insufficiency is an infrequent entity, mainly caused by autoimmune adrenalitis (up to 90% of the cases). Among the remaining etiologies, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage has been described in association with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia [1] and, more recently, with sporadic cases of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) [2,3], as expression of thrombosis in unusual sites including cerebral, splanchnic and adrenal veins. However, symptomatic adrenal insufficiency has rarely been described.

VITT is caused by antibodies that recognize platelet factor 4 and induce platelet activation with a significant stimulation of the coagulation system, leading to clinically relevant thromboembolic events [4, 5, 6]. In this setting, when thrombosis affects adrenal veins, an adrenal hemorrhagic infarction develops, and in bilateral involvement, adrenal insufficiency may be clinically manifested. Nevertheless, in large population-based cohorts and randomized clinical trials reporting cardiovascular and hemostatic events with Oxford-AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 [7, 8], adrenal bleeding has scarcely been described and adrenal insufficiency has not been reported.

Clinical manifestations of adrenal insufficiency are nonspecific and include fatigue, gastrointestinal complaints (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain) and postural hypotension, while most common laboratory findings include hyponatremia and hyperkalemia [9]. In cases of intercurrent severe stress an adrenal crisis (entity associated with high lethality) may be precipitated.

In conclusion, due to its nonspecific clinical manifestations and its potentially fatal course, it is very important to have a high index of suspicion for adrenal insufficiency in the setting of hypercoagulable states such as vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

JFV: conceptualization, writing original draft; MGI, MM and MRL: image data collection, critical revision; MFD: critical revision.

Funding

None

References

- 1.Rosenberger L.H., Smith P.W., Sawyer R.G., Hanks J.B., Adams R.B., Hedrick T.L. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage: the unrecognized cause of hemodynamic collapse associated with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(4):833–838. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206d0eb. PMID: 21242799; PMCID: PMC3101312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blauenfeldt R.A., Kristensen S.R., Ernstsen S.L., Kristensen C.C.H., Simonsen C.Z., Hvas A.M. Thrombocytopenia with acute ischemic stroke and bleeding in a patient newly vaccinated with an adenoviral vector-based COVID-19 vaccine. J Thromb Haemost. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jth.15347. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33877737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Agostino V., Caranci F., Negro A. A Rare Case of Cerebral Venous Thrombosis and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation Temporally Associated to the COVID-19 Vaccine Administration. J Pers Med. 2021;11(4):285. doi: 10.3390/jpm11040285. Published 2021 Apr 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greinacher A., Thiele T., Warkentin T.E., Weisser K., Kyrle P.A., Eichinger S. Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov-19 Vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(22):2092–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cattaneo M. Thrombosis with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome associated with viral vector COVID-19 vaccines [published online ahead of print, 2021 May 25] Eur J Intern Med. 2021;S0953-6205(21):00190–00194. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciccone A. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced cerebral venous thrombosis [published online ahead of print, 2021 May 25] Eur J Intern Med. 2021;S0953-6205(21) doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.05.026. 00185-00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pottegård A., Lund L.C., Karlstad Ø. Arterial events, venous thromboembolism, thrombocytopenia, and bleeding after vaccination with Oxford-Astrazeneca ChAdOx1-s in Denmark and Norway: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2021;373:n1114. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1114. Published 2021 May 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voysey M., Clemens S.A.C., Madhi S.A. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK [published correction appears in lancet. 2021 Jan 9;397(10269):98] Lancet. 2021;397(10269):99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bancos I., Hahner S., Tomlinson J., Arlt W. Diagnosis and management of adrenal insufficiency. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(3):216–226. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70142-1. Epub 2014 Aug 3. PMID: 25098712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]