Abstract

Background

Fremanezumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody (IgG2Δa) selectively targets the calcitonin gene-related peptide and has proven efficacy for the preventive treatment of migraine. In this study, we evaluated the long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of monthly and quarterly fremanezumab.

Methods

Episodic migraine and chronic migraine patients completing the 12-week double-blind period of the FOCUS trial entered the 12-week open-label extension and received 3 monthly doses of fremanezumab (225 mg). Changes from baseline in monthly migraine days, monthly headache days of at least moderate severity, days of acute headache medication use, days with photophobia/phonophobia, days with nausea or vomiting, disability scores, and proportion of patients achieving a ≥50% or ≥75% reduction in monthly migraine days were evaluated.

Results

Of the 807 patients who completed the 12-week double-blind treatment period and entered the open-label extension, 772 patients completed the study. In the placebo, quarterly fremanezumab, and monthly fremanezumab dosing regimens, respectively, patients had fewer average monthly migraine days (mean [standard deviation] change from baseline: − 4.7 [5.4]; − 5.1 [4.7]; − 5.5 [5.0]), monthly headache days of at least moderate severity (− 4.5 [5.0]; − 4.8 [4.5]; − 5.2 [4.9]), days per month of acute headache medication use (− 4.3 [5.2]; − 4.9 [4.6]; − 4.8 [4.9]), days with photophobia/phonophobia (− 3.1 [5.3]; − 3.4 [5.3]; − 4.0 [5.2]), and days with nausea or vomiting (− 2.3 [4.6]; − 3.1 [4.5]; − 3.0 [4.4]). During the 12-week open-label extension, 38%, 45%, and 46% of patients, respectively, achieved a ≥50% reduction and 16%, 15%, and 20%, respectively, achieved a ≥75% reduction in monthly migraine days. Disability scores were substantially improved in all 3 treatment groups. There were low rates of adverse events leading to discontinuation (<1%).

Conclusion

Fremanezumab demonstrated sustained efficacy up to 6 months and was well tolerated in patients with episodic migraine or chronic migraine and documented inadequate response to multiple migraine preventive medication classes.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03308968 (FOCUS).

Keywords: Migraine, Calcitonin gene-related peptide, CGRP, Long-term safety, Long-term efficacy

Introduction

The burden of migraine is substantial and it includes social and economic burdens in addition to functional impairments [1, 2], which are generally higher for patients who have failed ≥1 prior migraine preventive treatment [3–5]. Many patients with migraine either cannot tolerate the side effects, or do not respond to oral migraine preventive medications [6, 7]. As such, adherence to treatment is poor and the rate of patients discontinuing preventive therapy is high, especially among patients with chronic migraine (CM) [6, 7]. Given the poor adherence, efficacy, and tolerability, as well as the high rate of treatment discontinuations, patients with prior inadequate responses to multiple classes of migraine preventive medications are particularly in need of effective and tolerable long-term treatments for migraine prevention [8].

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is known to play a major role in migraine pathophysiology [9]. Biologic therapies targeting the CGRP pathway are the first preventive treatments for migraine that have been designed specifically to target the underlying pathophysiology of migraine [10]. Fremanezumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody (IgG2Δa), selectively targets α-CGRP and β-CGRP and is approved as a migraine preventive treatment in adults [11–13]. In previous double-blind (DB), placebo-controlled trials, fremanezumab demonstrated efficacy, with favorable safety and tolerability in both episodic migraine (EM) and CM patients [14–18]. In the two 12-week phase 3 HALO EM and HALO CM trials, fremanezumab significantly reduced the monthly average number of migraine days and the monthly number of headache days of at least moderate severity when compared with patients receiving placebo [14, 15]. In the HALO long-term safety study, both fremanezumab quarterly and fremanezumab monthly were well tolerated and demonstrated sustained improvements in monthly migraine days, headache days, and headache-related disability for up to 12 months in patients with migraine [19].

In the 12-week, randomized, DB period of the phase 3b FOCUS trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03308968), fremanezumab demonstrated efficacy and tolerability as a quarterly or monthly migraine preventive treatment in adults with EM or CM and documented prior inadequate response to 2 to 4 migraine preventive medication classes [18]. The objective of the open-label extension (OLE) of the FOCUS study was to further evaluate the long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of monthly and quarterly fremanezumab.

Methods

Study design and participants

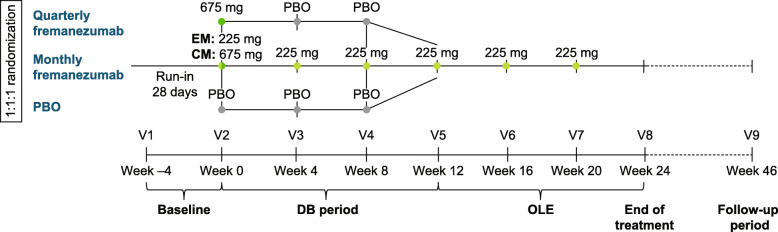

The FOCUS study was an international, multicenter, randomized, phase 3b trial consisting of a 12-week, DB, placebo-controlled treatment period and a 12-week OLE, with a final follow-up 6 months after the last dose of fremanezumab (Fig. 1). The FOCUS study has been described in detail in previous reports [18]; as such, key details are summarized below. Participants in the FOCUS study were adults (18–70 years), with a diagnosis of EM or CM at or before 50 years of age for ≥12 months prior to the screening visit. Participants with EM had a headache on ≥6 days, but < 15 days, per month with ≥4 days fulfilling criteria from the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3 beta version (ICHD-3 beta) for migraine, probable migraine, or use of triptans or ergot derivatives to treat an established headache. Participants with CM had a headache on ≥15 days per month, with ≥8 days fulfilling the ICHD-3 beta criteria for migraine, probable migraine, or use of triptans or ergot derivatives to treat an established headache [20].

Fig. 1.

FOCUS study design. PBO, placebo; EM, episodic migraine; CM, chronic migraine; V, visit; DB, double-blind; OLE, open-label extension

At the screening visit, study participants were required to have had a documented (in medical chart or by treating physician’s confirmation) prior inadequate response to 2 to 4 classes of migraine preventive medications within the past 10 years: angiotensin II receptor antagonists, anticonvulsants, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, onabotulinumtoxinA, or valproic acid. Inadequate response was defined as a lack of efficacy, poor tolerability, or treatment contraindicated/unsuitable for migraine prevention for the patient. For the DB period, eligible patients were randomized (1:1:1) to receive placebo or subcutaneously administered fremanezumab quarterly (675 mg/placebo/placebo) or monthly (EM: 225 mg/225 mg/225 mg; CM: 675 mg/225 mg/225 mg). All patients who completed the DB period were eligible to enter the nonrandomized, 12-week OLE and receive 3 monthly doses (225 mg) of fremanezumab (Fig. 1).

Outcomes

Results from the DB period and the OLE were stratified according to randomization group for the DB period. During the DB period and the OLE, for the following outcomes, efficacy was measured as the mean change from baseline (assessed during the 28-day baseline period before the first DB dose) during the 12 weeks after the first dose of the DB period and the OLE: monthly average number of migraine days, average monthly headache days of at least moderate severity, days of acute headache medication use, days with photophobia/phonophobia, and days with nausea/vomiting. Efficacy was also measured according to the proportion of patients achieving ≥50% and ≥75% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days in the 12 weeks after the first dose of the DB period and the OLE and as the mean change in disability from baseline through the 4 weeks after the last dose of study drug in the DB period and the OLE. Disability was evaluated by the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) [21] and the 6-item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) [22]. Safety and tolerability were measured by the rates of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs), and AEs leading to study discontinuation.

Statistical analysis

The safety analysis set comprised all randomly assigned participants who received ≥1 dose of study drug. Participants in the intent-to-treat analysis set who received ≥1 dose of study drug and had ≥10 days of postbaseline efficacy assessments for the primary outcome (modified intent-to-treat analysis set) were included in all efficacy analyses. Demographics, baseline characteristics, efficacy, and safety outcomes in each treatment group were summarized descriptively.

Results

Patients

Of the 838 patients randomized for the DB period, 807 (96%) entered the OLE (264, placebo group; 271, DB quarterly fremanezumab group; 272, DB monthly fremanezumab group). Of the patients entering the OLE, 772 (96%) completed the OLE (253, placebo group; 259, DB quarterly fremanezumab group; 260, DB monthly fremanezumab group); 92% of patients completed both the full 6 months of DB and OLE treatment. Overall, 35 (4%) patients discontinued treatment in the OLE, including 17 (2%) due to withdrawal of consent, 6 (<1%) due to AEs, 3 (<1%) due to lack of efficacy, 2 (<1%) each due to protocol deviations and lost to follow-up, 1 (<1%) due to noncompliance with study procedures, and 4 (<1%) due to other reasons.

Among the patients in the OLE, baseline characteristics were similar across treatment groups and resembled those in the DB treatment period (Table 1). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 46.4 (11.0) years, and patients ranged from 18 to 71 years of age; most patients were female (84%) and White (94%). The mean (SD) time since migraine diagnosis was 24.3 (13.3) years. More patients had CM (61%) than EM (39%), and 398 (49%) patients had a prior inadequate response to 2 migraine preventive medications.

Table 1.

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics According to DB Randomization (OLE Safety Analysis Set)

| Placeboa(n = 262) | Quarterly fremanezumaba(n = 271) | Monthly fremanezumaba(n = 274) | Total(n = 807) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 46.9 (11.2) | 46.0 (11.0) | 46.1 (11.0) | 46.4 (11.0) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 218 (83) | 226 (83) | 230 (84) | 674 (84) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 247 (94) | 258 (95) | 254 (93) | 759 (94) |

| Black/African American | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 4 (1) | 6 (<1) |

| Asian | 1 (<1) | 0 | 2 (<1) | 3 (<1) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Other | 1 (<1) | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 4 (<1) |

| Not reported | 12 (5) | 10 (4) | 12 (4) | 34 (4) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 71.3 (13.9) | 70.5 (13.3) | 71.1 (13.8) | 71.0 (13.7) |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 167.6 (9.0) | 167.6 (7.9) | 167.4 (7.6) | 167.6 (8.2) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 25.3 (4.1) | 25.0 (4.1) | 25.3 (4.4) | 25.2 (4.2) |

| Years since initial migraine diagnosis, mean (SD) | 24.3 (13.4) | 24.4 (12.9) | 24.3 (13.7) | 24.3 (13.3) |

| Migraine classification, n (%) | ||||

| Episodic migraine | 105 (40) | 102 (38) | 106 (39) | 313 (39) |

| Chronic migraine | 157 (60) | 169 (62) | 168 (61) | 494 (61) |

| Number of prior preventive medications failed, n (%) | ||||

| 2 | 131 (50) | 138 (51) | 129 (47) | 398 (49) |

| 3 | 77 (29) | 82 (30) | 94 (34) | 253 (31) |

| 4 | 54 (21) | 49 (18) | 49 (18) | 152 (19) |

| Monthly average number of migraine days, mean (SD)b | 14.4 (6.2) | 14.2 (5.6) | 14.0 (5.5) | 14.2 (5.8) |

| Headache days of at least moderate severity, mean (SD)b | 12.9 (5.9) | 12.5 (5.8) | 12.6 (5.7) | 12.7 (5.8) |

| Days per month of acute headache medication use, mean (SD)b | 12.4 (6.3) | 12.9 (6.2) | 12.1 (5.9) | 12.5 (6.1) |

| Days per month with photophobia/phonophobia, mean (SD)b | 9.9 (7.8) | 9.5 (6.8) | 9.4 (6.8) | 9.6 (7.2) |

| Days per month with nausea/vomiting, mean (SD)b | 6.4 (6.0) | 6.7 (5.9) | 6.6 (5.9) | 6.5 (5.9) |

| HIT-6 score, mean (SD)b | 64.1 (4.8) | 64.3 (4.3) | 63.9 (4.5) | 64.1 (4.5) |

| MIDAS score, mean (SD)b | 62.0 (57.4) | 62.2 (49.3) | 61.8 (51.3) | 62.0 (50.6) |

DB double-blind, OLE open-label extension, SD standard deviation, HIT-6 6-item Headache Impact Test, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment, mITT modified intent-to-treat

aAll patients in the OLE received fremanezumab 225 mg monthly

bOLE mITT analysis set

At baseline, for the DB placebo, DB quarterly fremanezumab, and DB monthly fremanezumab groups, the mean (SD) monthly average number of migraine days was 14.4 (6.2), 14.2 (5.6), and 14.0 (5.5), respectively, and mean (SD) headache days of at least moderate severity was 12.9 (5.9), 12.5 (5.8), and 12.6 (5.7), respectively. At baseline, for the DB placebo, DB quarterly fremanezumab, and DB monthly fremanezumab groups, the mean (SD) days per month of acute medication use was 12.4 (6.3), 12.9 (6.2), and 12.1 (5.9), respectively. At baseline, for the DB placebo, DB quarterly fremanezumab, and DB monthly fremanezumab groups, mean (SD) days per month with photophobia/phonophobia was 9.9 (7.8), 9.5 (6.8), and 9.4 (6.8), respectively, and mean (SD) days per month with nausea/vomiting was 6.4 (6.0), 6.7 (5.9), and 6.6 (5.9), respectively. At baseline, for the DB placebo, DB quarterly fremanezumab, and DB monthly fremanezumab groups, the mean (SD) HIT-6 score was 64.1 (4.8) points, 64.3 (4.3) points, and 63.9 (4.5) points, respectively, and mean (SD) MIDAS score was 62.0 (57.4) points, 62.2 (49.3) points, and 61.8 (51.3) points, respectively.

Efficacy

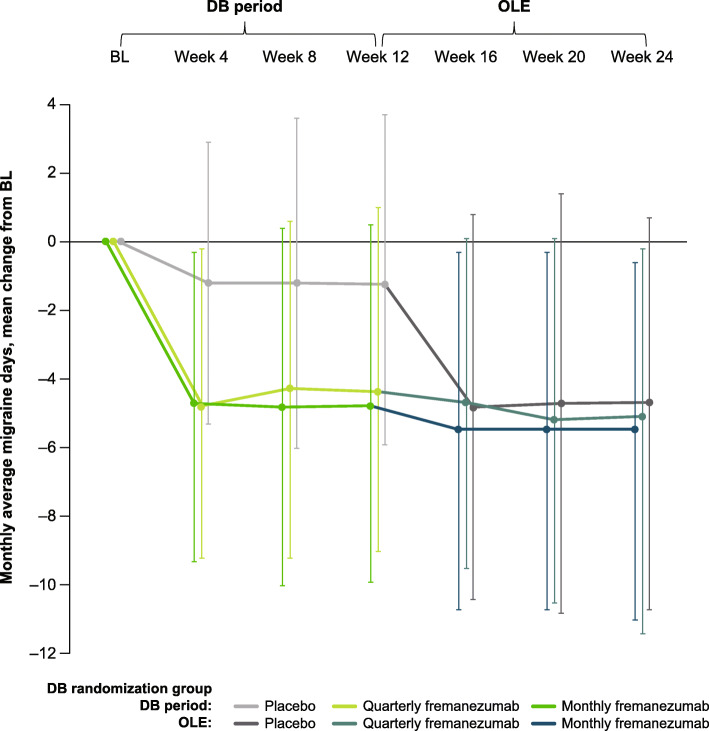

Over the 12-week DB period, the mean (SD) change from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days was: placebo, − 1.2 (4.0); quarterly fremanezumab, − 4.4 (4.2); and monthly fremanezumab, − 4.8 (4.4). Over the 12-week OLE, patients had fewer monthly average migraine days (mean [SD] change from baseline: DB placebo, − 4.7 [5.4]; DB quarterly fremanezumab, − 5.1 [4.7]; DB monthly fremanezumab, − 5.5 [5.0]; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean change from BL in the monthly average number of migraine days over 6 months (mITT).a BL, baseline; mITT, modified intent-to-treat; DB, double-blind; OLE, open-label extension. aAll patients in the OLE received fremanezumab 225 mg monthly

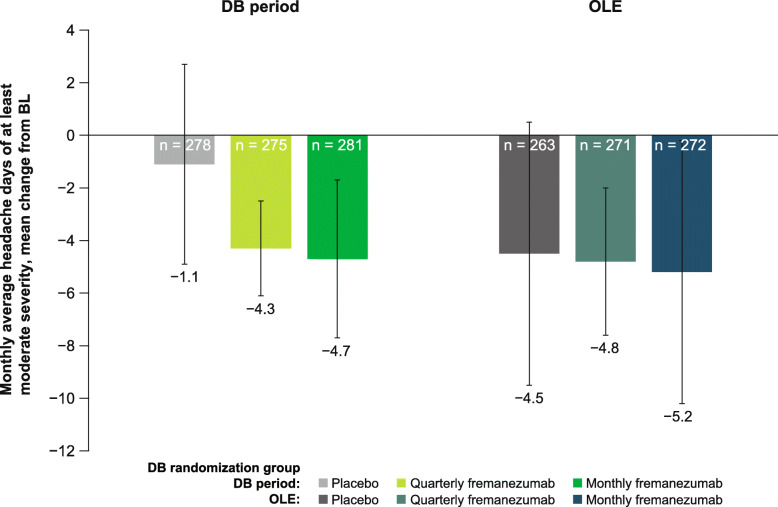

Over the 12-week DB period, the mean (SD) change from baseline in monthly headache days of at least moderate severity was: placebo, − 1.1 (3.8); quarterly fremanezumab, − 4.3 (4.1); and monthly fremanezumab, − 4.7 (4.6). Over the 12-week OLE, patients also had fewer monthly headache days of at least moderate severity (mean [SD] change from baseline: placebo, − 4.5 [5.0]; DB quarterly fremanezumab, − 4.8 [4.5]; DB monthly fremanezumab, − 5.2 [4.9]; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mean change from BL in the number of headache days of at least moderate severity in the DB period and the OLE (mITT).a BL, baseline; DB, double-blind; OLE, open-label extension; mITT, modified intent-to-treat. aAll patients in the OLE received fremanezumab 225 mg monthly

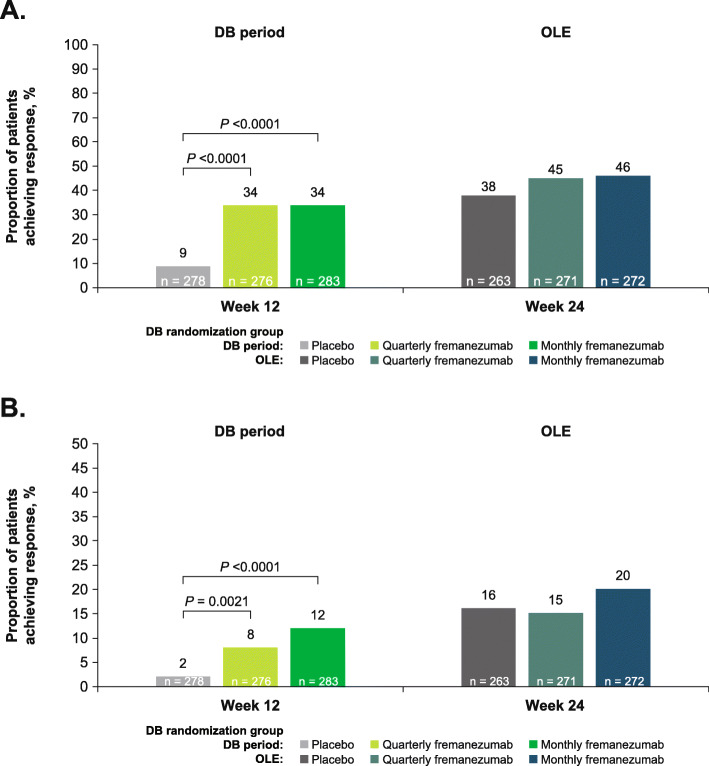

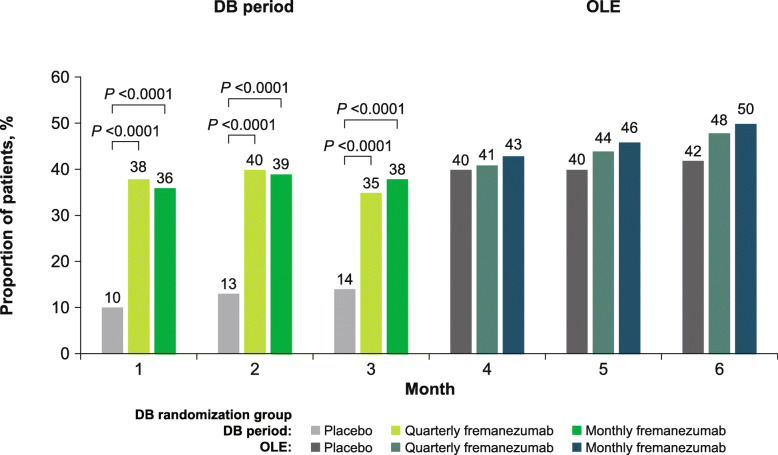

At 12 weeks of treatment in the DB period, 9% and 2% of patients in the placebo group achieved ≥50% and ≥ 75% reductions in the monthly average number of migraine days, respectively, compared with 34% and 8% in the quarterly fremanezumab group, and 34% and 12% in the monthly fremanezumab group. At 24 weeks, similar proportions of patients achieved ≥50% and ≥ 75% reductions in the monthly average number of migraine days across the placebo (38% and 16%), DB quarterly fremanezumab (45% and 15%), and DB monthly fremanezumab (46% and 20%) treatment groups (Fig. 4a and b). In addition, responder rates generally increased over time (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Proportion of patients achieving a ≥50% reduction and b ≥75% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days in the DB period and the OLE (mITT).a DB, double-blind; OLE, open-label extension; mITT, modified intent-to-treat. aAll patients in the OLE received fremanezumab 225 mg monthly

Fig. 5.

Proportion of patients achieving ≥50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days over 6 months (mITT).a mITT, modified intent-to-treat; DB, double-blind; OLE, open-label extension. aAll patients in the OLE received fremanezumab 225 mg monthly

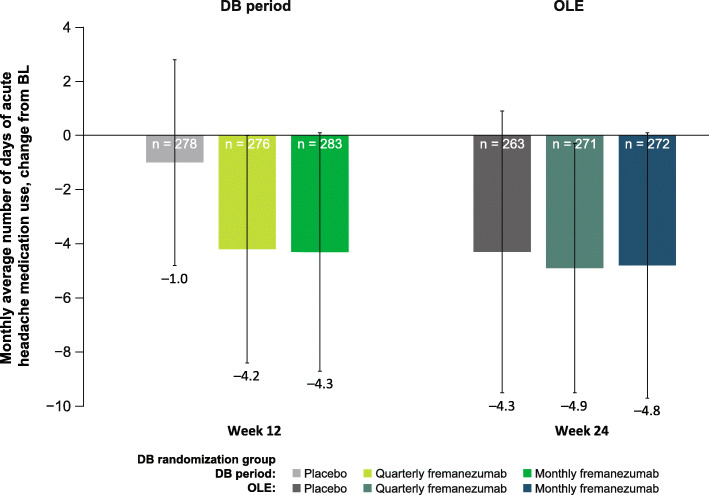

Over the 12-week DB period, the mean (SD) change from baseline in days per month of acute headache medication use was: placebo, − 1.0 (3.8); quarterly fremanezumab, − 4.2 (4.2); and monthly fremanezumab, − 4.3 (4.4). Over the 12-week OLE, patients had fewer days per month of acute headache medication use (mean [SD] change from baseline: placebo, − 4.3 [5.2]; DB quarterly fremanezumab, − 4.9 [4.6]; DB monthly fremanezumab, − 4.8 [4.9]; Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Mean change from BL in days of acute headache medication use in the DB period and the OLE (mITT).a BL, baseline; DB, double-blind; OLE, open-label extension; mITT, modified intent-to-treat. aAll patients in the OLE received fremanezumab 225 mg monthly

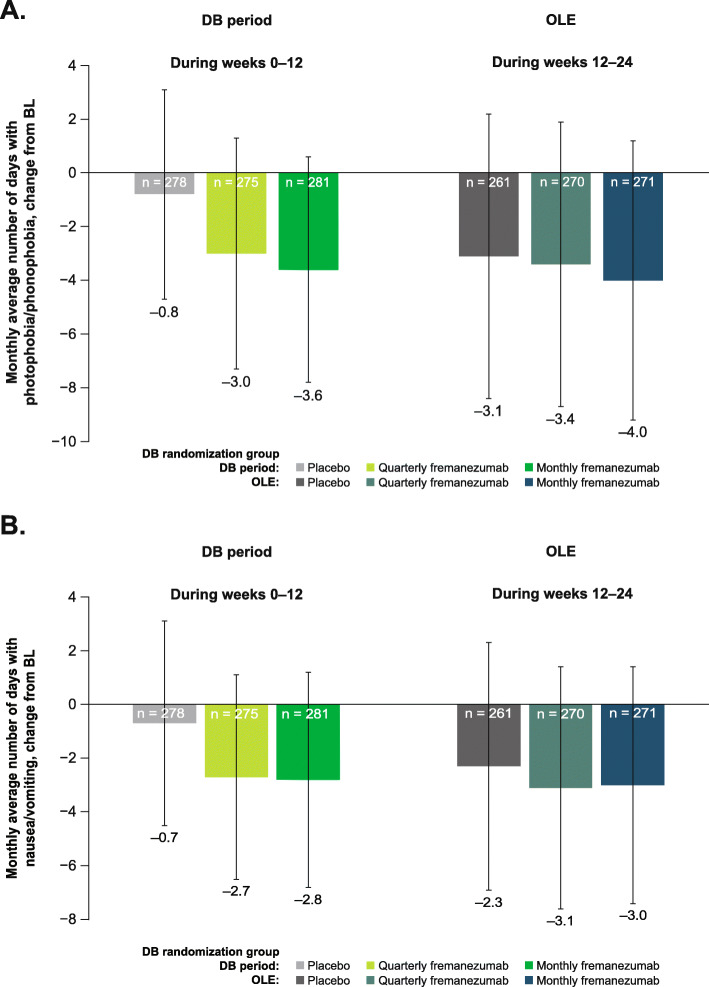

Over the 12-week DB period, the mean (SD) change from baseline in days per month with photophobia/phonophobia was: placebo, − 0.8 (3.9); quarterly fremanezumab, − 3.0 (4.3); and monthly fremanezumab, − 3.6 (4.2). The mean (SD) change from baseline in the monthly number of days with nausea and vomiting was: placebo, − 0.7 (3.8); quarterly fremanezumab, − 2.7 (3.8); and monthly fremanezumab, − 2.8 (4.0). Over the 12-week OLE, patients reported fewer days per month with photophobia/phonophobia (mean [SD] change from baseline: placebo, − 3.1 [5.3]; DB quarterly fremanezumab, − 3.4 [5.3]; DB monthly fremanezumab, − 4.0 [5.2]; Fig. 7a) and fewer days per month with nausea or vomiting (mean [SD] change from baseline: placebo, − 2.3 [4.6]; DB quarterly fremanezumab, − 3.1 [4.5]; DB monthly fremanezumab, − 3.0 [4.4]; Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

Mean change from BL in days with a photophobia/phonophobia and b nausea/vomiting in the DB period and the OLE (mITT).a BL, baseline; DB, double-blind; OLE, open-label extension; mITT, modified intent-to-treat. aAll patients in the OLE received fremanezumab 225 mg monthly

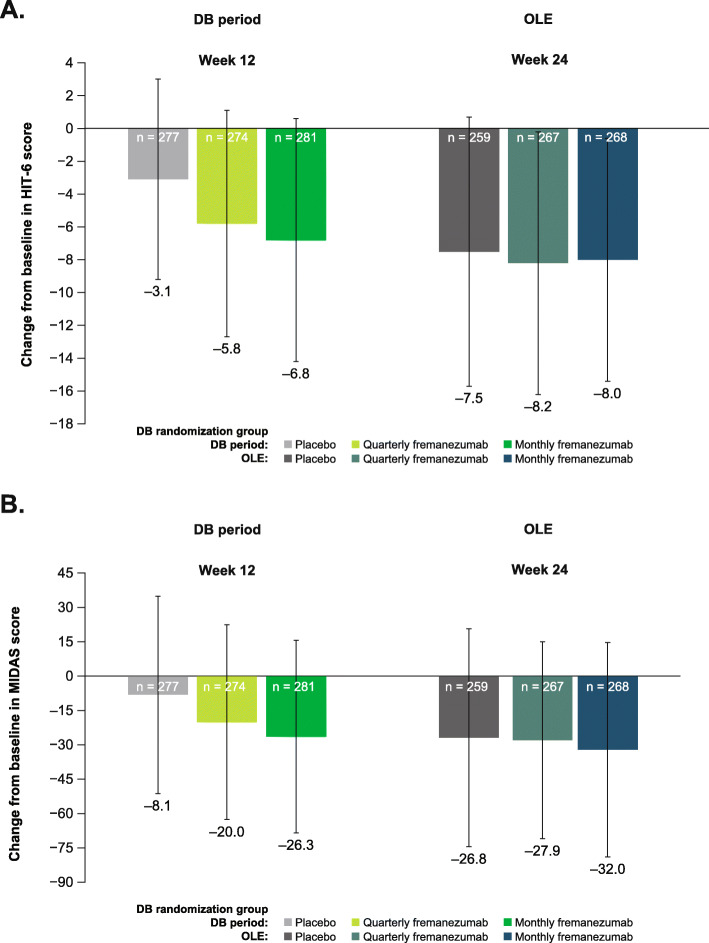

Over the 12-week DB period, the mean (SD) change from baseline in HIT-6 score was: placebo, − 3.1 (6.1); quarterly fremanezumab, − 5.8 (6.9); and monthly fremanezumab, − 6.8 (7.4). The mean (SD) change from baseline in MIDAS score was: placebo, − 8.1 (43.1); quarterly fremanezumab, − 20.0 (42.5); and monthly fremanezumab, − 26.3 (42.0). Over the 12-week OLE, patients had reductions in disability scores as measured by HIT-6 (mean [SD] change from baseline: placebo, − 7.5 [8.2]; DB quarterly fremanezumab, − 8.2 [8.0]; and DB monthly fremanezumab, − 8.0 [7.4]; Fig. 8a) and MIDAS (mean [SD] change from baseline: placebo, − 26.8 [47.6]; DB quarterly fremanezumab, − 27.9 [43.0]; and DB monthly fremanezumab, − 32.0 [46.8]; Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

Mean change in disability in the DB period and the OLE as measured by a HIT-6 and b MIDAS (mITT).a,b BL, baseline; DB, double-blind; OLE, open-label extension; HIT-6, Headache Impact Test; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment; mITT, modified intent-to-treat. aAll patients in the OLE received fremanezumab 225 mg monthly

Safety and tolerability

During the 12-week DB period, the incidences of AEs (placebo, 48%; quarterly fremanezumab, 55%; monthly fremanezumab, 45%), SAEs (all groups, 1%), treatment-related AEs (placebo, 20%; quarterly fremanezumab, 21%; monthly fremanezumab, 19%), and protocol-defined AEs of special interest (placebo, <1%; quarterly fremanezumab, 1%; monthly fremanezumab, 1%) were similar across treatment groups (Table 2). During the 12-week OLE, the incidences of AEs (placebo, 52%; DB quarterly fremanezumab, 55%; DB monthly fremanezumab, 57%), SAEs (all groups, 3%), treatment-related AEs (placebo, 16%; DB quarterly fremanezumab, 17%; DB monthly fremanezumab, 20%), and protocol-defined AEs of special interest (placebo, 2%; DB quarterly fremanezumab, <1%; DB monthly fremanezumab, 3%) were similar across treatment groups. Cardiovascular AEs were infrequent and similar across treatment groups (≤1%) during both the 12-week DB period and the 12-week OLE (Table 2). The most common AEs reported during the OLE were nasopharyngitis (8%), injection site erythema (6%), injection site induration (5%), migraine (4%), and injection site pain (3%). During OLE, 4 patients had abnormal systolic blood pressure values (placebo, 1 [<1%]; DB quarterly fremanezumab, 2 [<1%]; DB monthly fremanezumab, 1 [<1%]) while 10 patients had abnormal diastolic blood pressure values (placebo, 4 [2%]; DB quarterly fremanezumab, 3 [1%]; DB monthly fremanezumab, 3 [1%]). During OLE, 10 patients reported constipation: 6 (2%) in DB placebo group, 2 (<1%) in DB quarterly fremanezumab group, and 2 (<1%) in DB monthly fremanezumab group. Overall, 7 patients discontinued the OLE due to AEs, including 4 (2%) patients in the DB placebo group, 1 (<1%) patient in the DB quarterly fremanezumab group, and 2 (<1%) patients in the DB monthly fremanezumab group. As with the DB period of the study, there were no deaths reported in the OLE or the follow-up period of the study.

Table 2.

AEs in the DB Period and the OLE (Safety Analysis Set)

| Placebo | Quarterly fremanezumab | Monthly fremanezumab | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE, n (%) | DB period (n = 277) | OLEa (n = 262) | DB period (n = 276) | OLEa (n = 271) | DB period (n = 285) | OLEa (n = 274) |

| Any AE | 134 (48) | 137 (52) | 151 (55) | 149 (55) | 129 (45) | 155 (57) |

| Any SAEb, c | 4 (1) | 9 (3) | 2 (< 1) | 7 (3) | 4 (1) | 7 (3) |

| Treatment-related AE | 55 (20) | 41 (16) | 57 (21) | 47 (17) | 55 (19) | 56 (20) |

| Protocol-defined AE of special interestd | 2 (<1) | 4 (2) | 3 (1) | 2 (<1) | 3 (1) | 9 (3) |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AE leading to discontinuatione, f | 3 (1) | 4 (2) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 4 (1) | 2 (<1) |

| Cardiovascular AEs | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Extrasystoles | 0 | 2 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Palpitations | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tachycardia | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Bradycardia | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Left bundle branch block | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Coronary artery disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1)g |

AE adverse event, DB double-blind, OLE open-label extension, SAE serious adverse event, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, ULN upper limit of normal, INR international normalized ratio

aAll patients in the OLE received fremanezumab 225 mg monthly

bDB period: thoracic vertebral fracture, uterine leiomyoma, vulval cancer, hypoesthesia, and metrorrhagia in the placebo group; atrial fibrillation, cholelithiasis, clavicle fracture, foot fracture, respiratory fume inhalation, rib fracture, road traffic accident, back pain, nephrolithiasis, and vocal cord thickening in the fremanezumab groups

cOLE: retinal tear, anal polyp, acute cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, anaphylactic reaction, diverticulitis, abnormal INR, angiomyxoma, intracranial aneurysm, multiple sclerosis, optic neuritis, nephrolithiasis, renal colic, dysmenorrhea, endometriosis, menometrorrhagia, and menorrhagia in the fremanezumab groups

dOphthalmic-related AEs of at least moderate severity, events of possible drug-induced liver injury (AST or ALT ≥3 ULN, total bilirubin ≥2 ULN or INR >1.5), Hy’s law events, or events of anaphylaxis and severe hypersensitivity reactions

eDB period: chest discomfort, injection-site pain, and vulval cancer in the placebo group; palpitations, fatigue, cholelithiasis, road traffic accidents, and temporal arteritis in the fremanezumab groups

fOLE: upper abdominal pain, nausea, injection-site reactions, breast cancer, dizziness, headache, oropharyngeal pain, and hyperhidrosis in the placebo group; injection-site reactions, depressed mood, and asthma in the fremanezumab groups

gPatient experienced a non-serious event of coronary artery disease on day 211 of the study. The event was considered not related to study treatment by the investigator and was considered likely due to chronic pre-existing disease. The event was ongoing at the time of the last visit

Discussion

Results from this 12-week OLE of the FOCUS study demonstrate that treatment with fremanezumab can lead to substantial clinical benefit in patients with EM or CM who previously did not respond to up to 4 different classes of migraine preventive medications; furthermore, in combination with the results from the 12-week DB period [18], these data indicate sustained clinical benefit with fremanezumab for up to 6 months in these patients.

Migraine is associated with a significant burden of disease, and the burden is greater for patients who have failed prior treatments [3]. Furthermore, estimates suggest that a large proportion of patients with migraine have failed ≥1 prior migraine preventive treatment [3]. Additionally, most health technology assessment bodies only recommend reimbursements for monoclonal antibody migraine preventive medication treatments for patients who failed prior treatments. In the 12-week, phase 3, double-blind CONQUER trial of patients with 2 to 4 prior migraine preventive medication failures, patients receiving galcanezumab had 4.1 fewer monthly migraine days compared with 1.0 fewer day among patients receiving placebo [23]. In a 12-week, phase 2 trial of patients with CM and ≥2 prior preventive treatment failures, patients receiving erenumab 70 mg and erenumab 140 mg had 2.7 and 4.3 fewer monthly migraine days, respectively, when compared to placebo [24]. The 12-week, phase 3, double-blind LIBERTY study evaluated erenumab among adults with EM and prior unsuccessful treatment with 2 to 4 migraine preventive treatments, and patients receiving erenumab had 1.6 fewer monthly migraine days when compared to placebo [25]. In the current study, over the 12-week DB period, patients in the quarterly fremanezumab and monthly fremanezumab treatment groups had 4.4 and 4.8 fewer monthly average migraine days, respectively, when compared to baseline. Furthermore, improvements in monthly migraine days were sustained over 24 weeks of fremanezumab treatment, with patients in the DB quarterly fremanezumab and DB monthly fremanezumab treatment groups showing 5.1 and 5.5 fewer monthly migraine days, respectively, when compared to baseline. Similarly, with fremanezumab treatment, improvements across all efficacy outcomes were not only sustained but showed continued improvement up to 6 months. The responder rates generally increased over time, suggesting that perhaps patients can achieve greater clinical benefit over time. In addition, there was no evidence of tachyphylaxis during this study period.

Of the 838 patients randomized during the DB period, 807 (96%) entered the OLE. Of the patients entering the OLE, 772 (96%) completed the OLE. During both the DB period and the OLE, few patients discontinued the study due to AEs, with most discontinuations due to withdrawal of consent or protocol deviations. In clinical practice, adverse effects are a major reason for discontinuation of many migraine preventive medications. Results from the FOCUS study demonstrated a low rate of treatment-emergent AEs and discontinuations due to AEs. Rates of AEs, SAEs, treatment-related AEs, and protocol-defined AEs of special interest were similar between the DB period and the OLE. The favorable cardiovascular safety profile observed in the OLE was similar to the findings from the phase 2b/3 fremanezumab studies [26]. No safety signals were identified during the study. This demonstrates that fremanezumab is safe and well tolerated in this difficult-to-treat population. In addition, low rates of treatment persistence may occur with traditional migraine preventive medications, with observational studies showing persistence ranging from 19% to 79% at 6 months and 7% to 55% at 12 months [27]. The low percentage of patients who discontinued this study due to AEs demonstrates that fremanezumab was well tolerated, a finding that is further supported by the low rates of treatment-emergent AEs and SAEs observed during the study.

This study had a few limitations. The OLE was uncontrolled with no placebo group or an active comparator. In addition, only patients who received treatment benefit and completed the 12-week DB period participated in the OLE. Furthermore, longer-term treatment beyond 6 months has not been evaluated in this population.

Conclusions

In this 6-month study, patients with EM or CM and prior documented inadequate responses to 2 to 4 migraine preventive treatment classes had fewer monthly average migraine days, fewer headache days of moderate severity, fewer days of acute headache medication use, fewer days with photophobia and phonophobia, fewer days of nausea or vomiting, and reduced HIT-6 and MIDAS scores. Improvements in these outcomes in the OLE were also of greater magnitude than the improvements seen at the end of the 3-month DB period. In conclusion, findings from this FOCUS study indicate that fremanezumab is effective, safe, and well tolerated for up to 6 months in patients who had previously not responded to 2 to 4 classes of migraine preventive medications.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who participated in this study and their families, all investigators, site personnel, and the coordinating investigators. Medical writing support was provided by Dan Jackson, PhD, of MedErgy (Yardley, PA, USA), which was in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines and funded by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries (Petach Tikva, Israel).

Abbreviations

- CM

Chronic migraine

- CGRP

Calcitonin gene-related peptide

- DB

Double-blind

- EM

Episodic migraine

- OLE

Open-label extension

- ICHD-3 beta

International Classification of Headache Disorders 3 beta version

- MIDAS

Migraine Disability Assessment

- HIT-6

6-item Headache Impact Test

- AE

Adverse event

- SAE

Serious adverse events

- SD

Standard deviation

Authors’ contributions

MA, JMC, MG, VRC, SB, XN, YK, LJ, and H-CD contributed to drafting of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual concepts. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Petach Tikva, Israel.

Availability of data and materials

Anonymized data, as described in this manuscript, will be shared upon request from any qualified investigator by the author investigators or Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was done in full accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and any applicable national and local laws and regulations. All participants provided written informed consent before participation in the study. The final study protocol and informed consent form were reviewed and approved by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board at all participating study sites.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MA has received personal fees from AbbVie/Allergan, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. MA is the principal investigator for ongoing AbbVie/Allergan, Amgen and Lundbeck trials. MA has no ownership interest and does not own stocks of any pharmaceutical company. MA serves as associate editor of Cephalalgia and associate editor of The Journal of Headache and Pain. MA is president of the International Headache Society (IHS). JMC, MG, VRC, SB, XN, YK, and LJ are employees of Teva Pharmaceuticals. H-CD has received honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contribution to advisory boards, or oral presentations from Alder BioPharmaceuticals, Allergan, Amgen, electroCore, Ipsen, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novartis, Pfizer, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Weber & Weber; electroCore provided financial support for research projects. H-CD has received research support from the German Research Council, the German Ministry of Education and Research, and the European Union. H-CD serves on the editorial boards of Cephalalgia and The Lancet Neurology. H-CD chairs the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the German Society of Neurology and is a member of the Clinical Trials Committee of the IHS.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Deuschl G, Beghi E, Fazekas F, Varga T, Christoforidi KA, Sipido E, Bassetti CL, Vos T, Feigin VL (2020) The burden of neurological diseases in Europe: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Public Health. 5(10):e551–e567. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30190-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Feigin VL, Vos T, Nichols E, Owolabi MO, Carroll WM, Dichgans M, Deuschl G, Parmar P, Brainin M, Murray C (2020) The global burden of neurological disorders: translating evidence into policy. Lancet Neurol 19(3):255–265. 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30411-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Martelletti P, Schwedt TJ, Lanteri-Minet M, Quintana R, Carboni V, Diener HC, Ruiz de la Torre E, Craven A, Rasmussen AV, Evans S, Laflamme AK, Fink R, Walsh D, Dumas P, Vo P (2018) My Migraine Voice survey: a global study of disease burden among individuals with migraine for whom preventive treatments have failed. J Headache Pain. 19(1):115. 10.1186/s10194-018-0946-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.American Headache Society The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59:1–18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipton RB, Munjal S, Alam A, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML, Schwedt TJ, Dodick DW. Migraine in America Symptoms and Treatment (MAST) study: baseline study methods, treatment patterns, and gender differences. Headache. 2018;58(9):1408–1426. doi: 10.1111/head.13407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, Buse DC, Varon SF, Maglinte GA, Wilcox TK, Kawata AK, Lipton RB. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the second International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS-II) Headache. 2013;53(4):644–655. doi: 10.1111/head.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Chia J, Matthew N, Gillard P, Hansen RN, Devine EB. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: a retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(5):470–485. doi: 10.1177/0333102416678382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global Burden of Disease 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32647-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hargreaves R, Olesen J. Calcitonin gene-related peptide modulators – the history and renaissance of a new migraine drug class. Headache. 2019;59(6):951–970. doi: 10.1111/head.13510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silberstein SD, Cohen JM, Yeung PP. Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of migraine. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19(8):763–771. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2019.1627323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tepper SJ. History and review of anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) therapies: from translational research to treatment. Headache. 2018;58(Suppl 3):238–275. doi: 10.1111/head.13379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoy SM. Fremanezumab: first global approval. Drugs. 2018;78(17):1829–1834. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-1004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AJOVY (fremanezumab-vfrm) [prescribing information]. North Wales: Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.; Revised 2020. Available from: https://www.ajovyhcp.com/globalassets/ajovy/ajovy-pi.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2021

- 14.Bigal ME, Edvinsson L, Rapoport AM, Lipton RB, Spierings EL, Diener HC et al (2015) Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of TEV-48125 for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study. Lancet Neurol. 14(11):1091–1100. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00245-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Bigal ME, Dodick DW, Rapoport AM, Silberstein SD, Ma Y, Yang R, Loupe PS, Burstein R, Newman LC, Lipton RB. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of TEV-48125 for preventive treatment of high-frequency episodic migraine: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(11):1081–1090. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, Yeung PP, Goadsby PJ, Blankenbiller T, Grozinski-Wolff M, Yang R, Ma Y, Aycardi E. Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(22):2113–2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Bigal ME, Yeung PP, Goadsby PJ, Blankenbiller T, Grozinski-Wolff M, Yang R, Ma Y, Aycardi E. Effect of fremanezumab compared with placebo for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(19):1999–2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrari MD, Diener HC, Ning X, Galic M, Cohen JM, Yang R, Mueller M, Ahn AH, Schwartz YC, Grozinski-Wolff M, Janka L, Ashina M. Fremanezumab versus placebo for migraine prevention in patients with documented failure to up to four migraine preventive medication classes (FOCUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10203):1030–1040. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31946-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goadsby PJ, Silberstein SD, Yeung PP, Cohen JM, Ning X, Yang R, Dodick DW. Long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of fremanezumab in migraine: a randomized study. Neurology. 2020;95(18):e2487–e2499. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) (2018) The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 38:1–211 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;56(Supplement 1):S20–S28. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.suppl_1.S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang M, Rendas-Baum R, Varon SF, Kosinski M. Validation of the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) across episodic and chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(3):357–367. doi: 10.1177/0333102410379890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulleners W, Kim B-K, Lainez M, Lanteri-Minet M, Aurora S, Nichols R et al (2020) A randomized, placebo-controlled study of galcanezumab in patients with treatment-resistant migraine: double-blind results from the CONQUER study. Neurology. 94:162

- 24.Ashina M, Tepper S, Brandes JL, Reuter U, Boudreau G, Dolezil D, Cheng S, Zhang F, Lenz R, Klatt J, Mikol DD. Efficacy and safety of erenumab (AMG334) in chronic migraine patients with prior preventive treatment failure: a subgroup analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(10):1611–1621. doi: 10.1177/0333102418788347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reuter U, Goadsby PJ, Lanteri-Minet M, Wen S, Hours-Zesiger P, Ferrari MD, Klatt J. Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two-to-four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet. 2018;392(10161):2280–2287. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silberstein SD, McAllister P, Ning X, Faulhaber N, Lang N, Yeung P, Schiemann J, Aycardi E, Cohen JM, Janka L, Yang R. Safety and tolerability of fremanezumab for the prevention of migraine: a pooled analysis of phases 2b and 3 clinical trials. Headache. 2019;59(6):880–890. doi: 10.1111/head.13534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hepp Z, Bloudek LM, Varon SF (2014) Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. J Manag Care Pharm. 20(1):22–33. 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.1.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data, as described in this manuscript, will be shared upon request from any qualified investigator by the author investigators or Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd.