Abstract

Aim:

This study aims to study the expression of podoplanin in tumor cells as well as the lymphatic vessels (LVs) in both tumoral and peritumoral areas and correlate the importance of the lymphatic microvascular density (LMVD) in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and its metastatic potential.

Materials and Methods:

D2–40 expression and LV density (LVD) were assessed using antibody D240, in 45 diagnosed cases of all the three grades of OSCC. D2–40 expression was evaluated in both epithelial cells as well as the LVs.

Results:

D2–40 expression in OSCC showed two different patterns - diffuse and focal. LMVD was calculated and difference in peritumoral and intra tumoral LVs was also assessed. A marked increase was seen we progressed from well-differentiated tumor to poorly differentiated ones, but this difference was found to be statistically nonsignificant. D2–40 immunostaining also highlighted the presence of lymphatic invasion present within the tumors which was detected by the presence of tumor emboli within the LVs. Overall, no significant correlation was found between D240 epithelial positivity and LVD.

Conclusion:

The expression of podoplanin in tumor cells and lymphatics when correlated with histopathological status and clinically with the lymph node status can definitely help in the adjuvant therapies used in OSCC.

Keywords: D240, lymphatic microvessel density, oral squamous cell carcinoma, podoplanin

INTRODUCTION

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) being a complex disease, is one of the most common cancers existing in present world, with an annual incidence of more than 500,000 cases worldwide. It has various origins including the oral cavity, pharynx and larynx.[1,2] Although efforts are being performed for early detection with the use of newer molecular markers and adjuvant therapies, but still morbidity and mortality ratios are constantly rising at an alarming rate. Therefore, we need an insight into the biology of OSCC and examination of molecular changes occurring within, to understand which lesion has a greater risk of metastasis. These underlying changes are directly related to tumor progression and plays an essential role in determining the aggressiveness of the tumors.[3]

Although there is considerable evidence obtained in genetic and xenotransplant tumor models that tumor lymphangiogenesis promotes lymphatic tumor spread, it has remained controversial whether human tumors might actively induce lymphangiogenesis.[4] It is believed that there exists a correlation of tumor lymphangiogenesis with lymph node metastasis which can be assessed using lymphatic microvessel density (LMVD) in the tumors.

In recent studies, lymph node metastasis has been documented as one of the most adverse prognostic factors. However, it still remains controversial whether intra- or peritumoral lymphangiogenesis serves as a prognostic indicator of tumor progression. Therefore, identification of newer molecular markers which detect lymphatic vessel (LV) proliferation and metastasis through these channels presents as a big challenge in the field of targeted therapies.[5]

Podoplanin, a mucin-like transmembrane glycoprotein is highly and specifically expressed in lymphatic endothelial cells.[1,2,6] Recent literature shows that podoplanin may be expressed in certain tumor cells, including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cells, raising a possibility that podoplanin may have biologic functions in tumor cells.[2] It has thus attracted interest as a marker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis and is yet to be completely explored.

Thus, the present study aimed to study the expression of podoplanin in tumor cells as well as the LVs in both tumoral and peritumoral areas and correlate the importance of the LMVD in OSCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present retrospective study was conducted in the department of oral pathology, by including 45 paraffin-embedded tissue blocks, retrieved from the archives of the department. These samples were divided into three groups: Group 1: Well-differentiated OSCC, Group 2: Moderately differentiated OSCC and Group 3: Poorly differentiated OSCC cases. According to the inclusion criteria only those cases were included which had proper records regarding its tumor grade, lymph node status. The paraffin-embedded tissues were cut into 4 μ thick sections for subsequent histologic examinations using both H and E staining and immunohistochemical evaluation using anti-D2–40 monoclonal antibodies (DAKO, North America Carpenteria CA, USA). Equipment used for capturing the images included Nikon Research Microscope (ECLIPSE 80i) and CCD Video Camera (NIKON DS-U2, 5.03).

Evaluation of lymphatic vessels

The evaluation of LMVD, its quantification and morphology was carried out by counting positively stained D2–40 LVs using the criteria given by Weidner et al.[7] The vessel was considered as one which showed dark brown staining on the periphery and had a visible lumen, clearly separated from adjacent microvessels and from other connective tissue components. All the positive slides were evaluated at low magnification to identify the most vascular areas (hot spot areas). Analysis was performed under × 200 magnifications and an average of 10 hot spot fields was taken to calculate LMVD.

Immunohistochemical evaluation of D2–40 positive tumor cells

Podoplanin expression within tumor cells was scored by the criteria initially used by Yuan et al.,[1] i.e., 0%; 1%–10%; 11%–30%; 31%–50%; 51%–80%; and 81%–100% of the tumor cells were positive, quantitative scores from 0 to 5 were assigned, respectively. The staining intensity was rated on a scale of 0–3 (0 = negative, 1 = weak, 2 = moderate and 3 = strong). A German immunoreactive score (IRS) as given by Rodrigo JP et al.[8] was calculated for each slide by multiplying the quantitative and staining intensity scores. An IRS score above the median (7 or higher) was considered high reactivity and 0–6 as weak reactivity.

Statistical analysis

All the data were tabulated and sent for statistical analysis. Means and standard deviations for lymphatic microvessel density and D2–40 epithelial score were calculated for all the groups. Data were further examined for statistical significance (P value) using: One-way ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test and Mann–Whitney test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant; while P < 0.001 was considered as highly statistically significant.

RESULTS

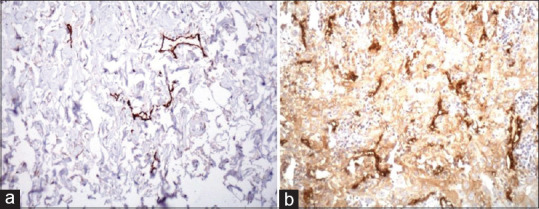

The overall mean LMVD observed in OSCC among all the groups, came to be 67.60 ± 5.73. It was observed that the D2–40-positive lymph vessels were unevenly distributed throughout the tumor with intratumoral lymph vessels was found to be small and more collapsed [Figure 1a]. While in contrast, those LVs which were located at the invasive front of tumors were found to be enlarged and dilated collapsed [Figure 1b]. Further, it was seen that mean LMVD in well-differentiated SCC was minimum with a mean of 48.05 ± 54.12 and was maximum in poorly differentiated SCC with a mean of 84.95 ± 28.19. When mean LMVD was compared between normal oral mucosa and OSCC, a statistically significant increase in LVMD was observed (P < 0.001). Whereas when the differences in mean LVMD between the 3 grades of OSCC were compared with each other it was observed that though a marked increase occurred as we progressed from well-differentiated tumor to poorly differentiated ones, but this difference was found to be statistically nonsignificant [Table 1].

Figure 1.

D2–40 positive lymphatic vessels both peri tumoral (a); and intra tumoral (b)

Table 1.

Lymphatic microvessel density and D2-40 epithelium score in all the three groups of oral squamous cell carcinoma

| Groups | LMVD | D240 epithelium score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum LMVD | Maximum LMVD | Mean±SD | Minimum score | Maximum score | Mean±SD | |

| Group I (well differentiated OSCC) | 0 | 79 | 48.05±54.12 | 5 | 12.4 | 9.46±1.29 |

| Group II (moderately differentiated OSCC) | 3 | 145 | 69.80±32.41 | 3 | 16 | 8.06±6.55 |

| Group III (poorly differentiated OSCC) | 16 | 267 | 84.95±28.19 | 1 | 15.8 | 4.20±2.16 |

LMVD: Lymphatic microvessel density, SD: Standard deviation, OSCC: Oral squamous cell carcinoma

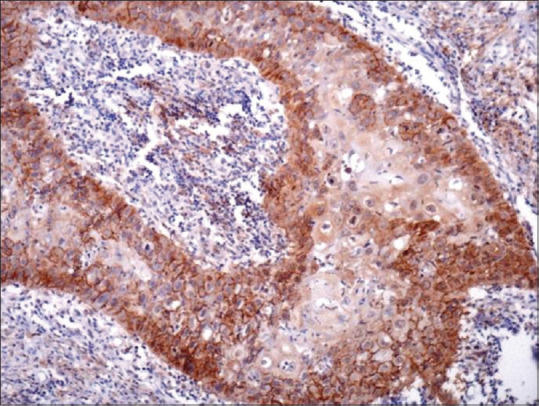

D2–40 immunostaining also highlighted the presence of lymphatic invasion present within the tumors which was detected by the presence of tumor emboli within the LVs [Figure 2]. We observed that 32 cases out of total 45 cases of OSCC demonstrated tumor emboli within LVs. Out of these 32 positive cases 26 cases showed lymph node metastasis and 6 were without any metastasis. Predominantly, poorly differentiated SCC showed highest tumor emboli as in comparison with the other grades and this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.005). This suggests that poorly differentiated SCC in comparison to other two grades of SCC has a higher rate of metastasis.

Figure 2.

The presence of tumor emboli within the lymphatic vessels

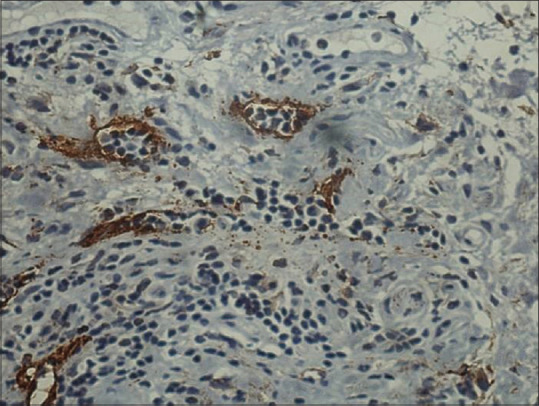

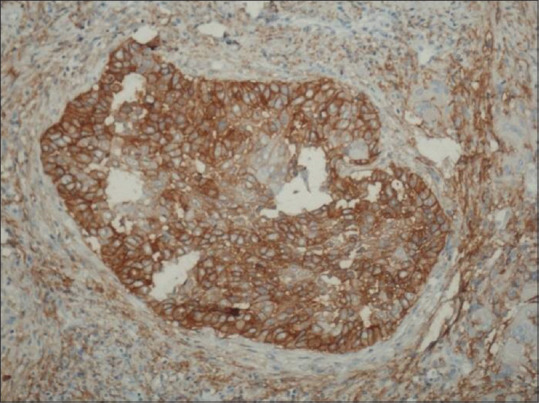

When we observed the epithelial D2–40 score, it was observed that 72.3% of all the cases showed staining positivity. Almost 100% of cases of well-differentiated carcinoma, 68% of cases of moderately differentiated carcinoma and 32% of cases of poorly differentiated carcinoma showed high D2–40 expression [Table 1]. The most significant thing observed was pattern of staining which could be related to degree of differentiation. This included first, a focal expression pattern in the membranous pattern in peripheral layers (the basal and suprabasal layers) of the proliferating tumor cells [Figure 3]. The other most predominant pattern was diffuse staining (both membranous and cytoplasmic) pattern [Figure 4]. Well-differentiated OSCC showed predominantly focal pattern (80%), moderately differentiated OSCC 52% presented with focal and rest the diffuse pattern at the invasive front, and 93% of poorly differentiated OSCC showed diffuse pattern at the invasive front.

Figure 3.

The presence of focal staining pattern of D2–40-positive tumor epithelial cells

Figure 4.

The presence of diffuse staining pattern of D2–40-positive tumor epithelial cells

DISCUSSION

D2–40 (immunoglobulin 1), a commercially available monoclonal antibody, recognized as a specific antibody against human podoplanin and a selective marker for lymphatic endothelium. The immunostaining of D2–40 is now widely used for the detection of tumor lymphangiogenesis in many human cancers.[9]

Lymphangiogenesis, the growth of LVs, is considered to be an important process in the development of tumor metastases. An increase in the number of LVs in the tumor stroma has been shown to correlate with lymph node metastasis and is a predictor of clinically meaningful outcomes in several malignancies.[5] However, there is still an important lack of information about the relationship of lymphangiogenesis in OSCC.

Tumor-associated LV density (LVD) is most frequently assessed by counting the number of immunostained vessels in tumor sections, as defined by Weidner et al.[8] The majority of intratumoral lymph vessels observed in our study were small and collapsed whereas in contrast, LVs located at the invasive edge were often enlarged and dilated. Our results were in accordance with the results of Franchi et al. who reported that peritumoral lymphatics was significantly higher in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cases with lymph node metastasis. Thus, they indicated that peritumoral lymphangiogenesis may be an indicator of the risk of lymph node metastasis in patients with HNSCC. In another study done by Longatto Filho et al.[9] on the significance of LVD in premalignant lesions and carcinomas of the uterine cervix reported significant differences in LVD among all categories of preinvasive and invasive lesions with LVD in invasive lesions to be significantly greater than in preinvasive lesions. Overall, we can say that lymphangiogenesis in OSCC might be used as an important factor to access the progression of the disease and to detect lymphatic metastasis, so as to recognize those patients which are at higher risk.[10,11]

D2–40 immunostaining also highlighted the presence of lymphatic invasion present within the tumors. Thus, the presence of such tumor emboli suggests a higher rate of metastasis associated with poorly differentiated SCC. These findings were supported by Dumoff et al.[12] and Yuan et al.[1]

As it is known that well-differentiated tumors are usually less invasive than those poorly differentiated, it was seen that mean D2–40 score in well-differentiated tumors was higher when compared to mean D2–40 score in poorly differentiated tumors. The difference between the means when compared was also statistically significant. The results of our study were in accordance with the results shown by Rodrigo et al.[7] who also reported that well-differentiated carcinomas exhibited significantly higher levels of podoplanin, compared to moderately or poorly differentiated carcinomas. Thus, they suggested the role of podoplanin expression in the initiation rather than the progression of laryngeal cancers. In contrast Schacht et al.[4] reported absence of podoplanin expression in well-differentiated carcinomas where as our results show intense focal podoplanin expression in the peripheral layers of the tumor islands. Our results suggest importance of podoplanin expression at the invasive front in poorly differentiated OSCC as they present with a marked potential for local progression and lymphovascular invasion. Thus, high levels of podoplanin can be correlated with of high frequency for lymph node metastasis.

In lesions showing focal expression of podoplanin, the cells of the peripheral layer of the tumor showed positive staining whereas the inner cell nests showed the absence of staining. This pattern was most prominent in well-differentiated OSCC in comparison to poorly differentiated where diffuse staining pattern was most predominant especially in the invasive front areas. These results can be supported by the tumor initiating cells concept and this was supported by the work done by some other authors such as Shimada et al. and Rodrigo et al.[7]

Finally, if we talk about the correlation between both the aspects of podoplanin in tumor, i.e., LMVD and tumor cells positivity, we observed so significant correlation within these two variables, but we can say that when both these factors are considered along with the progression, invasion and metastasis of the tumors, then definitely there is a significance and we can use podoplanin as a prognostic and a therapeutic marker in OSCC. Similar findings were reported by Cîrligeriu et al.[5] whereas Longatto Filho et al.[9] reported no significant correlation and no association between D2 and 40 tumor cell expression and LVD of the tumor. On the other hand, we also stress that podoplanin expression alone cannot be sufficient for tumor progression because many lesions exhibited the protein expression only in the basal cell layers.[13,14,15] Hence, to assess the prognostic role of podoplanin and its use as a therapeutic agent we need more of such studies with a large sample size so as to assess its accurate role in the morbidity and mortality of OSCC patients.[16]

Thus, if we talk about clinical significance of the present study, it can be said that as anti-podoplanin acts as a marker of LECs, which is most commonly expressed at invasive front of poorly differentiated OSCC as compared to other two grades of OSCC. Thus, we can interpret that poorly differentiated tumors have an increased risk of tumor invasion and lymph node metastasis and ultimately bad prognosis clinically. The anti-lymphangiogenetic therapies which are recent in treatment modalities, helps to lower the number of LVs and systemic metastasis rate. Various studies have also suggested that inhibiting lymphangiogeneis might be easier than then destroying the preexistent LVs.

CONCLUSION

We can conclude that this study evaluates that utility of podoplanin in the assessment of assessing the metastatic potential of OSCC and helps in providing additional insight beyond current clinical and histopathological evaluations. Thus, the expression of podoplanin in tumor cells and lymphatics when correlated with histopathological status and clinically with the lymph node status can definitely help in the adjuvant therapies used in OSCC.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yuan P, Temam S, El-Naggar A, Zhou X, Liu DD, Lee JJ, et al. Overexpression of podoplanin in oral cancer and its association with poor clinical outcome. Cancer. 2006;107:563–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawaguchi H, El-Naggar AK, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Ren H, Fan YH, Feng L, et al. Podoplanin: A novel marker for oral cancer risk in patients with oral premalignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:354–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali MA. Lymphatic microvessel density and the expression of lymphangiogenic factors in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17:486–92. doi: 10.1159/000151572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schacht V, Dadras SS, Johnson LA, Jackson DG, Hong YK, Detmar M. Up-regulation of the lymphatic marker podoplanin, a mucin-type transmembrane glycoprotein, in human squamous cell carcinomas and germ cell tumors. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:913–21. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62311-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cîrligeriu L, Cimpean AM, Raica M, Doroş CI. Dual role of podoplanin in oral cancer development. In Vivo. 2014;28:341–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadota K, Huang CL, Liu D, Nakashima N, Yokomise H, Ueno M, et al. The clinical significance of the tumor cell D2-40 immunoreactivity in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;70:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis – Correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigo JP, García-Carracedo D, González MV, Mancebo G, Fresno MF, García-Pedrero J. Podoplanin expression in the development and progression of laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:48. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longatto Filho A, Oliveira TG, Pinheiro C, de Carvalho MB, Curioni OA, Mercante AM, et al. How useful is the assessment of lymphatic vascular density in oral carcinoma prognosis? World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:140. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margaritescu C, Raica M, Pirici D, Simionescu C, Mogoanta L, Stinga AC, et al. Podoplanin expression in tumor-free resection margins of oral squamous cell carcinomas: an immunohistochemical and fractal analysis study. Histol Histopathol. 2010;25:701–11. doi: 10.14670/HH-25.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyahara M, Tanuma J, Sugihara K, Semba I. Tumor lymphangiogenesis correlates with lymph node metastasis and clinicopathologic parameters in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2007;110:1287–94. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumoff KL, Chu CS, Harris EE, Holtz D, Xu X, Zhang PJ, et al. Low podoplanin expression in pretreatment biopsy material predicts poor prognosis in advanced-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated by primary radiation. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:708–16. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raica M, Cimpean AM, Ribatti D. The role of podoplanin in tumor progression and metastasis. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2997–3006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Astarita JL, Acton SE, Turley SJ. Podoplanin: Emerging functions in development, the immune system, and cancer. Front Immunol. 2012;3:283. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franchi A, Gallo O, Massi D, Baroni G, Santucci M. Tumor lymphangiogenesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A morphometric study with clinical correlations. Cancer. 2004;101:973–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birner P, Schindl M, Obermair A, Breitenecker G, Kowalski H, Oberhuber G. Lymphatic microvessel density as a novel prognostic factor in early-stage invasive cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 2001;95:29–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010120)95:1<29::aid-ijc1005>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]