To the Editor:

We read with interest the article “Autoimmune hepatitis developing after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine: Causality or casualty?” by Bril et al. recently published in Journal of Hepatology.1 In this case, autoimmune hepatitis had some atypical features such as the absence of immunoglobulin G elevation and the presence of eosinophils on liver histology.

We recently observed a case of severe cholestatic hepatitis occurring after the administration of m-RNA-BNT162b1 (Comirnaty©, Pfeizer Biontech), with no development of autoantibodies and with the presence of eosinophil infiltrate at liver histology. The patient responded well to steroid treatment, similarly to autoimmune hepatitis.

The patient, a 43-year-old woman, presented to the hospital on February the 4th with jaundice and itching. At admission, total bilirubin was 17.54 mg/dl (direct bilirubin 12.94), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 52 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 51 U/L. Personal history was negative, except a mild dyslipidaemia with intermittent ALT increase, treated with diet (ALT and cholesterol maximum level 50 U/L and 285 mg/dl, respectively). Because of venous insufficiency, she took ginkgo-biloba in August 2020, withdrawn next October, more than 100 days before admission. She was a sanitary assistant so she received the Comirnaty vaccine (first dose January the 12th, second February the 2nd). Itching started on January 27th and by February the 4th, she noticed jaundice. No other adverse events related to the vaccine were reported.

Abdominal examination was negative; she had mild abdominal pain in right hypochondrium. Ultrasonography, CT scan and cholangioMRI showed normal liver and biliary system. Seromarkers ruled out hepatitis A, B, C, and E; CMV, EBV and HIV. HCV-RNA and HBV-DNA tested also negative. Autoimmune study was negative (anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-smooth muscle, anti-liver/kidney microsomal type-1, antimitochondrial, anti-extractable nuclear antigens). Finally, gamma-globulins (including subclasses), coagulation, ceruloplasmin, blood count, platelets, iron status, IL-6 and thyroid function were normal. Serum albumin was slightly low (2.8 g/dl) and molecular tests for SARS-CoV-2 on rhino-pharyngeal swabs were repeatedly negative, while antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 showed effective immunological response to vaccination (SARS-CoV-2 S1-S2 IgG 179 UA/ml).

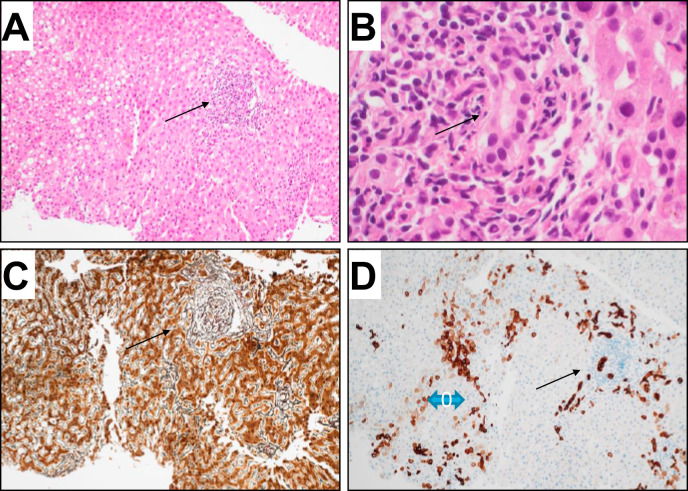

Liver biopsy showed moderate portal inflammatory infiltrate and interface hepatitis in the portal tract with biliary injury and mild ductular proliferation; in the lobule, we observed spotty necrosis, lymphocytes along the sinusoid, focal moderate steatosis and intranuclear glycogen inclusions. No sinusoidal dilatation or fibrosis. Immunostaining with cH7-Ab, showed mild ductular proliferation and diffuse immunoreactivity in hepatocytes zone 1-2 (Fig.1 ).

Fig. 1.

Histology of liver biopsy.

(A) H&E stain shows the histology of liver biopsy. The portal tract does not show fibrosis (C reticulin stain), but a moderate inflammatory infiltrate with interface hepatitis (arrow). The bile duct is surrounded by inflammatory cells and shows polymorphism of cholangiocytes (arrow). CK7 immunoreactivity is evident both in bile ducts and in hepatocytes (zone 1 and 2 blue arrow). (A,C,D 20x; B 60x).

N-acetyl-cysteine (9 g i.v. for 3 days) was administered at day 3 from admission. Nevertheless, bilirubin increased to 29.15 mg/dl (direct bilirubin of 19.9 mg/dl) with ALT 171 U/L and AST 132 U/L on day 10. Therefore, steroids were started (methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg/day) observing a slow decrease of liver function tests until complete normalization in 8 weeks’ time.

The case was reported to Italian sanitary authority (AIFA, Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco) and the patient was warned about re-exposure to the vaccine.

The new mRNA vaccines protect against infectious diseases by triggering an immune response. In registration trials, no cases of hepatitis were recorded.2 The association between vaccine and autoimmune manifestations has been reported in different settings.[3], [4], [5], [6] Our patient did not develop autoantibodies, nor liver histology showing typical signs of autoimmune damage. Nevertheless, 2 factors suggest immune-mediated hepatitis: the first is the timeline from vaccine to liver alteration which may correspond with the development of the immune response. The second, is the excellent response to steroids. Besides these hypotheses, the pathogenetic mechanism of this possible form of hepatitis obviously remains to be clarified. Drugs can induce toxic hepatitis,7 SARS-CoV-2 infection has been associated with the development of autoimmunity3 and there are also cases of drug-induced hepatitis with features of autoimmunity.8 Like the case reported by Bril et al.,1 eosinophil infiltrate was present at histology; this feature is more often observed in toxic or drug-related liver injury but also in autoimmune hepatitis.7 Our patient had non underlying chronic liver disease but only an intermittent observation of mild hypertransaminasemia related to hyperlipidaemia. With regard to the previous use of ginkgo-biloba, it seems unlikely related to hepatitis as it was discontinued about 100 days before the onset of jaundice. Moreover, the antioxidant properties of ginkgo-biloba have been described to prevent liver fibrosis in patients with chronic viral hepatitis9 and, although potential hepatic toxicity has been proposed,10 it has never been reported to cause severe liver damage before.

We are aware that a clear causality between vaccine and hepatitis cannot be established and our aim is not to discourage clinicians from investigating other causes or questioning the importance of vaccination against COVID-19. Despite this and in the light of the previous case, we believe it is important to inform the scientific community as we could be facing a possible immune-mediated hepatitis, induced by vaccine and presenting with different features, which shows excellent response to steroid therapy.

Financial support

No financial support was obtained for this letter to the editor.

Authors’ contributions

Francesca Lodato: patient’s care, writing of the manuscript and revision of the final version of the manuscript. Anna Larocca: patient’s care and revision of the final version of the manuscript. Antonietta D’Errico: pathology examination. Vincenzo Cennamo: made a critical revision of the letter to the Editor and revision of the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Francesca Lodato, Anna Larocca, Antonietta D’Errico and Vincenzo Cennamo declare no conflict of interest.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Footnotes

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.07.005.

Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bril F., Al Diffalha S., Dean M., Fettig D.M. Autoimmune hepatitis developing after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine: causality or casualty? J Hepatol. 2021 Jul;75(1):222–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 31;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrenfeld M., Tincani A., Andreoli L., Cattalini M., Greenbaum A., Kanduc D., et al. Covid-19 and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2020 Aug;19(8):102597. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zulfiqar A.A., Lorenzo-Villalba N., Hassler P., Andrès E. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura in a patient with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):e43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowles L., Platton S., Yartey N., Dave M., Lee K., Hart D.P., et al. Lupus anticoagulant and abnormal coagulation tests in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 16;383(3):288–290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee E.J., Cines D.B., Gernsheimer T., Kessler C., Michel M., Tarantino M.D., et al. Thrombocytopenia following pfizer and moderna SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Am J Hematol. 2021 May 1;96(5):534–537. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL clinical practice guidelines: drug-induced liver injury. J Hepatol. 2019 Jun;70(6):1222–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Boer Y.S., Kosinski A.S., Urban T.J., Zhao Z., Long N., Chalasani N., et al. Drug-induced liver injury network. Features of autoimmune hepatitis in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Jan;15(1):103–112.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang C.F., Zhang C.Q., Zhu U.H., Wang J., Xu H.W., Ren W.H. Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 alleviates hepatic fibrosis and sinusoidal microcirculation disturbance in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterol Res. 2008 doi: 10.4021/gr2008.10.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y.Y., Lu X.Y., Sun J.L., Wang Q.Q., Zhang Y.D., Zhang J.B., et al. Potential hepatic and renal toxicity induced by the biflavonoids from Ginkgo biloba. Chin J Nat Med. 2019 Sep;17(9):672–681. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(19)30081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.