A common complication of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is circuit and patient thrombosis, even when systemic anticoagulation is utilized. However, there are no evidence-based deep vein thrombosis (DVT) screening recommendations for this patient population. We sought to describe the prevalence of DVT among patients supported with ECMO at our institution where they are screened routinely. We found that 45% of ECMO survivors were diagnosed with a DVT. The majority of these DVTs were associated with ECMO cannulas. We conclude that screening for DVT in this high-risk population is clinically justified.

Our institution initiates anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin in all ECMO patients except those that are immediately post-cardiotomy. We continue anticoagulation throughout the duration of ECMO unless there are bleeding complications. We adjust heparin dose by anti-factor Xa (anti-Xa) level with a general target of 0.3 – 0.7 IU/mL. We obtain daily and as needed twice daily thromboelastrograms (TEG) and further refine our goal anti-Xa range based on the TEG. We target a reaction (R) time of 1.5 – 2 times baseline and, when this is achieved, re-evaluate the appropriate anti-Xa range. Survivors are routinely screened for DVT with venous duplex ultrasonography of all four extremities within 24 – 48 hours after explant.

This retrospective study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (IRB # 410219). The charts of 111 adult patients supported with ECMO were reviewed. Patient data was extracted from the electronic medical record. A DVT was defined as a partial or complete occlusion of a deep vein, and a cannula-associated DVT was defined as a DVT at an ECMO cannulation site. For simplicity, the degree of anticoagulation was quantified by reporting the fraction of days that the mean daily anti-Xa level was between 0.3 – 0.7 IU/mL.

A total of 110 patients were included in the study, excluding one who arrested during cannulation (Table 1). The median age was 47 years (range 18 – 79) and 60% were men. Fifty-eight (53%) patients were supported with veno-venous (VV-) ECMO, 48 (43%) with veno-arterial (VA-) ECMO, and four (4%) with veno-venous-arterial- (VVA-) ECMO. One patient who was cannulated for VA-ECMO and later converted to VV-ECMO was included in the VA-ECMO group for analysis. The majority of patients (94%) received therapeutic anticoagulation during extracorporeal support, most commonly with unfractionated heparin. Anticoagulation was not initiated in seven patients because of active bleeding or death shortly after cannulation. In the cohort that was treated with heparin, the mean daily anti-Xa levels were in the therapeutic range for 43% of ECMO-days.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, mortality, and prevalence of DVT

| Overall n=110 |

VV-ECMO n=58 |

VA-ECMO n=48 |

VVA-ECMO n=4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years | 47 (18-79) | 34 (18-69) | 59 (19-75) | 48 (25-79) |

| Male sex | 66 (60) | 33 (57) | 31 (65) | 2 (50) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31 (15-53) | 27 (18-53) | 33 (15-53) | 46 (46) |

| No. available | 66 | 30 | 35 | 1 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio* | 57 (30-298) | 61 (30-158) | 55 (33-298) | 50 (50) |

| No. available | 62 | 31 | 30 | 1 |

| SOFA score* | 11 (3-20) | 10 (3-20) | 12 (8-17) | |

| No. available | 52 | 29 | 23 | 0 |

| Indication and duration of ECMO | ||||

| Indication for ECMO | ||||

| ARDS | 44 (40) | 40 (69) | 2 (4) | 2 (50) |

| Asthma | 14 (13) | 13 (22) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 43 (39) | 1 (2) | 40 (83) | 2 (50) |

| Other | 9 (8) | 4 (7) | 5 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Duration of ECMO, days | 6 (1-43) | 7 (1-43) | 6 (1-16) | 4 (1-18) |

| Site of venous cannulation and cannula type | ||||

| Right internal jugular vein | 58 | 55 | 1 | 2 |

| Dual lumen | 44 (76) | 44 (80) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Single lumen | 10 (17) | 8 (15) | 1 (100) | 1 (50) |

| Not specified | 4 (7) | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) |

| Right femoral vein | 37 | 13 | 21 | 3 |

| Left femoral vein | 20 | 1 | 19 | 0 |

| Right atrium | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Superior vena cava | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Inferior vena cava | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mortality | ||||

| ECMO mortality | 37 (37) | 14 (26) | 19 (43) | 4 (100) |

| Hospital mortality | 49 (49) | 20 (34) | 25 (57) | 4 (100) |

| Prevalence and site of deep vein thrombosis | ||||

| Patients with at least one DVT† | 29 (45) | 25 (56) | 4 (14) | - |

| Total number of DVTs | 35 | 29 | 6 | - |

| Cannula-associated | 24 (69) | 22 (86) | 2 (33) | - |

| Non-cannula associated | 11 (31) | 7 (24) | 4 (67) | - |

Data represented as n (%) or median (range). ECMO=extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. DVT=deep vein thrombosis. BMI=body mass index. SOFA=Sequential Organ Failure Assessment. ARDS=acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Calculated as close as possible to the time of ECMO cannulation.

Prevalence expressed as percentage of ECMO survivors (n=64 overall, n=44 VV-ECMO, n=29 VA-ECMO, n=0 VVA-ECMO) diagnosed with DVT.

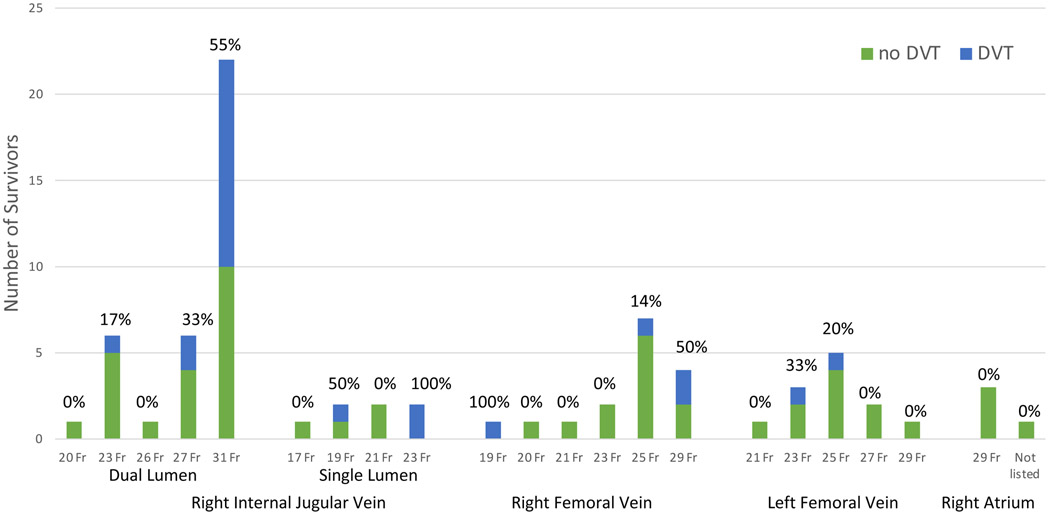

Thirty-seven patients died on extracorporeal support and nine were transferred for cardiac transplant evaluation. Of the remaining 64 patients, 56 (88%) were screened for a DVT. A total of 35 DVTs were diagnosed in 29 patients; the overall prevalence of DVT among ECMO-survivors was 45%. Twenty-four (69%) DVTs were ECMO cannula-associated (Figure 1), eighteen (75%) of which were located in the right internal jugular vein. There were no DVTs diagnosed in the patients who were centrally cannulated. One pulmonary embolism (PE) was diagnosed based on clinical suspicion; we did not routinely screen for PE unless clinically indicated. There were higher rates of DVT among patients supported with VV-ECMO (58% compared with 31% in VA-ECMO) and in patients in whom dual-lumen cannulas were utilized (44% compared with 33% in single-lumen cannulas). The prevalence of DVT was also higher among patients with larger cannulas. While other studies have shown an association between duration of ECMO and clot formation (1), this was not observed in our population. The median duration of ECMO was 6 days (range 2 – 15) among ECMO survivors diagnosed with DVT and 7 days (range 3 – 34) among those without DVT. We also did not observe a relationship between the degree of anticoagulation and formation of DVT. Heparin was therapeutic for 53% of the time in patients who were diagnosed with DVT and 45% of the time in patients who were not.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of DVT among ECMO survivors by cannula size and type. The majority of DVTs (55%) were diagnosed in patients who had 31 Fr dual-lumen cannula. DVT=deep vein thrombosis; ECMO=extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Although thrombosis is a known complication of ECMO, there is a paucity of literature regarding anticoagulation strategies, DVT screening practices and the prevalence of DVT in ECMO patients. The HELP-ECMO study compared low-dose heparin to standard-dose heparin and reported only five DVTs in 32 ECMO cases (prevalence 16%). However, patients were not routinely screened for DVTs in this study (2). We employ a routine screening strategy and found that nearly half of the patients supported with ECMO were diagnosed with a DVT and that approximately two-thirds of these DVTs were ECMO cannula-associated. Two retrospective reviews of 103 and 102 subjects and one prospective study of 70 subjects reported rates of DVT of 18%, 81% and 85%, respectively, during ECMO (1, 3, 4). These studies differ from ours in that they only included patients supported with VV-ECMO, and they utilized single-lumen cannulas in the vast majority of cases. One study suggested that larger caliber, dual-lumen cannulas may increase the risk of thrombosis (3). In recent years, the use of dual-lumen cannulas for VV-ECMO has increased; this strategy has advantages including increased mobility for patients and single-site, upper body configuration (5). Our institution uses dual-lumen cannulas in the majority of VV-ECMO cases. We noted a higher rate of DVTs in this population, with the highest rate among patients who had the largest cannula (31 Fr). Given the potential benefits of dual lumen cannulas, this observation needs to be confirmed in future studies.

There are several reasons why ECMO might predispose to DVT formation. First, the prevalence of DVT among critically ill patients is high due to prolonged immobility. A large meta-analysis reported the prevalence of DVT in the intensive care unit is 12%, despite adequate prophylaxis (6). ECMO may further increase the risk of DVT because of the vascular endothelial injury caused by ECMO cannulas and from alteration of blood flow around the cannula. Extracorporeal circulation has also been shown to activate the coagulation cascade (7). We observed that the rate of DVT was higher in VV-ECMO, despite the fact that we use the same anticoagulation strategy for all configurations. Heparin dose was more often therapeutic in patients supported with VV-ECMO compared with VA-ECMO (50% versus 32% respectively) and median duration of ECMO was also similar among survivors of VV- and VA-ECMO (6 and 7 days respectively), making these explanations less likely. Possible explanations for the higher rates of DVT associated with VV-ECMO may be that it tends to be run at lower flow rates with more blood stasis, larger cannulas, or that acute respiratory failure itself is an established risk factor for venous thromboembolism (8).

There are several limitations to this study. It is a single-center retrospective review with missing data. Not all ECMO survivors received a screening ultrasound, and some survivors that were screened did not have satisfactory ultrasound examinations. We did not collect follow-up or post-mortem data on the patients who died on ECMO, which could have led to underestimation of the prevalence of thromboembolism. We do not have detailed flow rate data available. The clinical relevance of DVTs detected with screening ultrasound (especially in the upper extremities) is not known, but we submit that the diagnosis and treatment of such is appropriate given that ECMO patients tend to be very fragile and the provision of ECMO is a resource-intense endeavor. The goals of this study were descriptive, as we were underpowered to detect an independent association between ECMO configuration and/or cannula size and risk of DVT.

In summary, DVT is a frequent complication of ECMO. Nearly half of the patients supported with ECMO at our institution were diagnosed with a DVT. Routine surveillance in patients supported with ECMO is justified and prudent.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: This work was supported by R01 HL141268 (C.E.V.) and T32 HL134625 (A.A.).

Footnotes

Disclosures: C.E.V. served as a past consultant for Maquet Cardiovascular. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Trudzinski FC, Minko P, Rapp D, Fahndrich S, Haake H, Haab M, et al. Runtime and aPTT predict venous thrombosis and thromboembolism in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a retrospective analysis. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubron C, McQuilten Z, Bailey M, Board J, Buhr H, Cartwright B, et al. Low-Dose Versus Therapeutic Anticoagulation in Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Pilot Randomized Trial. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(7):e563–e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper E, Burns J, Retter A, Salt G, Camporota L, Meadows CI, et al. Prevalence of Venous Thrombosis Following Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Patients With Severe Respiratory Failure. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(12):e581–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menaker J, Tabatabai A, Rector R, Dolly K, Kufera J, Lee E, et al. Incidence of Cannula-Associated Deep Vein Thrombosis After Veno-Venous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Asaio j. 2017;63(5):588–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tipograf Y, Gannon WD, Foley NM, Hozain A, Ukita R, Warhoover M, et al. A Dual-Lumen Bicaval Cannula for Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109(4):1047–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malato A, Dentali F, Siragusa S, Fabbiano F, Kagoma Y, Boddi M, et al. The impact of deep vein thrombosis in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis of major clinical outcomes. Blood Transfus. 2015;13(4):559–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urlesberger B, Zobel G, Zenz W, Kuttnig-Haim M, Maurer U, Reiterer F, et al. Activation of the clotting system during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in term newborn infants. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1996;129(2):264–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahloul M, Chaari A, Kallel H, Abid L, Hamida CB, Dammak H, et al. Pulmonary embolism in intensive care unit: Predictive factors, clinical manifestations and outcome. Ann Thorac Med. 2010;5(2):97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]