Abstract

5-Aminolevulinic acid (ALA)-induced fluorescence cystoscopy has established itself in the detection of flat and/or small lesions. This is explained by the simple fact that there is increased uptake of ALA, altered activity of certain enzymes, and altered intracellular redistribution and storage of protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) in the malignant cells. Intracellular PPIX allows red fluorescence detection. In this preliminary study, the efficacy of 5-ALA-induced fluorescent urine cytology was compared with conventional cytology in the diagnosis of bladder tumours. In this prospective study, patients ≥18 years of age admitted to the department of urology with non-malignant conditions formed the controls and patients ≥18 years of age with imaging confirmed bladder tumours formed the study group. Freshly voided urine sample was collected from these patients and divided into two samples of 50 cc each. One of these samples was sent in for conventional cytology examination, whereas the other sample was sent in for 5-ALA fluorescent photo dynamic diagnosis. Conventional cytology and 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology were evaluated by the same pathologist. A total of 100 patients were included in the study of which 75 patients were controls and the remaining 25 were patients with bladder tumours. The sensitivity of conventional cytology and 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology was 64% and 100% respectively, whereas the specificity was 96% and 98.67% respectively. The sensitivity of conventional cytology was 61.19% in low-grade cancers as compared to 75% in high-grade cancers, whereas the sensitivity was 100% with 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology both in low- as well as high-grade cancers. Our study shows that 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology is highly sensitive test to diagnose bladder cancer and shows a significant difference especially in low-grade bladder cancer when compared to conventional cytology.

Keywords: 5-Aminolevulinic acid, Urothelial carcinoma, Cytology, Sensitivity, Specificity

Introduction

There has been an increased attention focused recently on the use of photodynamic technology using 5-ALA (5-aminolevulinic acid) as a photosensitizer to solve the clinical problem of bladder cancer.[1, 2] ALA-PDD (photo dynamic diagnosis) is indeed useful to detect and identify CIS (carcinoma in situ) in the bladder during TURBT (Transurethral resection of bladder tumour). 5-ALA is a natural amino acid found in animals and plants that is a common precursor of haemoglobin and chlorophyll. Endogenous 5-ALA, synthesized from succinyl coenzyme A and glycine in mitochondria, and exogenously administered 5-ALA follow the same metabolic synthetic pathway.[3] Protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) is a metabolic product of 5-ALA and accumulates in the mitochondria following its administration[4] PpIX is then catalysed by ferrochelatase and binds with ferrous ion resulting in the production of heme.[3]

Cancer cells utilize the glycolysis pathway for production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), but do not run the tricarboxylic acid cycle or electron transport chain in mitochondria even in normoxia, which is called the Warburg effect and is typical for hyperplasia.[3] The ferrochelatase is inactive in these conditions, because of the lack of electron supply from the tricarboxylic acid cycle, which is essential for reduction of ferric ion to ferrous ion to complete the production of heme by ferrochelatase.[3] Biological features that are common to cancer cells, such as abnormal activity of transporters including ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCG2) and porphyrin synthetic enzymes, can promote PpIX production and inhibit PpIX catabolism. This results in excess accumulation of PpIX in cancer cells. In particular, PpIX is accumulated 9–16-fold higher in urothelium and is highly tumour selective.[3, 5] PpIX is photoactive and gets excited at certain wavelengths of light, particularly visible blue light (375–445 nm), and emits red fluorescence (600–740 nm).[3] This has been the underlying principle of ALA-PDD.[6, 7] Similarly, this principle has been used to make the diagnosis of bladder cancer.[8–10]

The feasibility of diagnosing bladder cancer using 5-ALA was first reported in 1994.[11] Kriegmair et al.[11] instilled 5-ALA intravesically in 68 patients, followed by fluorescence cystoscopy with violet light from a krypton ion laser that produced fluorescence excitation. Tumour lesions were sharply marked with brightly shining red fluorescence. Correlation of fluorescence and microscopic findings gave a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 68.5%. Currently, 5-ALA is approved as a photosensitizer of PDD for carcinoma around the world.[12] Recently, Nakai et al.[13] reported on the 5-ALA staining of urine specimens and showed that PDD sensitivity to be effective, compared with conventional cytology in bladder tumours (82% vs. 49%, respectively), particularly in low-grade and low-stage tumours, and to have comparable specificity (80% vs. 100%, respectively). In this preliminary study, we have evaluated the efficacy of 5-ALA-induced fluorescent urine cytology in comparison with conventional cytology in the diagnosis of bladder tumours.

Materials and Methods

This prospective study was conducted after obtaining clearance from the University/Institutional ethical committee. Patients ≥18 years of age admitted to the department of urology with non-malignant conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), urinary stone, urinary tract infection (UTI), uretero-pelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction, and radiological cystitis formed the controls. Patients ≥18 years of age with imaging (ultrasonography/computed tomography) confirmed bladder tumours formed the study group. Freshly voided urine sample was collected from these patients and divided into two samples of 50 cc each. One of these samples was sent in for conventional cytology examination, whereas the other sample was sent in for 5-ALA fluorescent cytology diagnosis.

Urine Samples and Treatment with 5-ALA

The urine sample was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min and the supernatant was decanted. The pellet was suspended in minimum essential medium (MEM) with 5-aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, 2020), and the concentration was adjusted to 200 μg/mL. Then, the suspension was stored in the dark at 37 °C for 2 h. After that, the sample was centrifuged again at 1500 rpm for 5 min, and the pellet was resuspended in MEM. Finally, the urine sample was tested for protoporphyrin IX fluorescence using a fluorescent microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE Ni; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at appropriate settings (excitation wavelength of 405 nm and emissions wavelength of 600–650 nm).

Evaluation

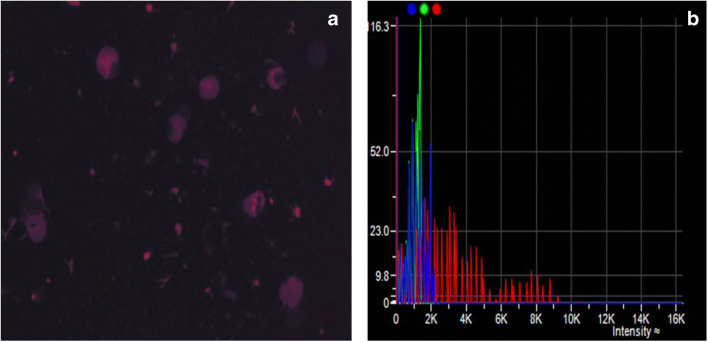

Conventional cytology and 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology were evaluated by the same pathologist using the same urine sample. The conventional urine cytology was considered either negative or positive for malignant cells based on the “The Paris system for reporting urinary cytology”. The 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology showing no red light or dark red was classified as negative and that showing clear red as positive. The final reading was confirmed by two pathologists (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

a shows cells emitting faint red fluorescence suggestive of a non-malignant cell. b Histogram of frequency (x-axis) versus intensity (y-axis) of a non-malignant cell

Comparison with Histopathology

All patients with imaging confirmed bladder tumour underwent cystoscopy/biopsy/transurethral resection of bladder tumour. The surgical specimens were sent in for histopathological examination and reported by the same pathologist. The reports of histopathology were compared to results of conventional cytology and 5-ALA induced fluorescent cytology.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analysed using the Wilcoxon test or chi-square test. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using (SPSS version 22.0. Armonk, Chicago, USA).

Results

During the study period Dec 2019–Aug 2020, a total of 100 patients were included in the study of which 75 patients were controls and the remaining 25 were patients admitted to the urology wards with imaging confirmed bladder tumours. The demographics of the patients was as shown in Table 1. Of the 75 patients who were controls, 20 (26.67%) had urinary stones, 30 (40%) had benign prostatic hyperplasia, 20 (26.67%) were admitted for reconstructive surgery, and 5 (6.67%) had chronic renal failure awaiting surgery.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients

| No | Variables | Controls (n 75) | Bladder tumour (n 25) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age (years) < 40 | 20 (26.67%) | – |

| 41–50 | 5 (6.67%) | 5 (20%) | |

| 51–60 | 30 (40%) | – | |

| 61–70 | 15 (20%) | 10 (40%) | |

| 71–80 | 5 (6.67%) | 10 (40%) | |

| Median Age | 56 ± 15.75 | 67 ± 12.54 | |

| 2 | Gender Male | 45(60%) | 25(100%) |

| Female | 30(40%) | – | |

| 3 | Co-morbidities hypertension | 20 (26.67%) | 10 (40%) |

| Type II diabetes M | 10 (13.33%) | 5 (20%) |

The conventional cytology was negative for malignant cells in 72 patients in the control group (Table 2) whereas it was negative in 74 patients with 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology. Conventional cytology was positive for malignant cells in 16/25 (64%) cases, whereas ALA-induced fluorescent cytology was positive in all 25 (100%) cases of bladder tumours. The specificity of conventional cytology in comparison with 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology was 96%versus 98.67% (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Results of conventional cytology in comparison with 5-ALA fluorescent cytology

| Conventional cytology | 5-ALA fluorescent cytology | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| negative | positive | negative | Positive | |

| Controls (n = 75) | 72 | 3 | 74 | 1 |

| Bladder tumour (n = 25) | 9 | 16 | – | 25 |

| Sensitivity | 64% | 100% | ||

| Specificity | 96% | 98.67% | ||

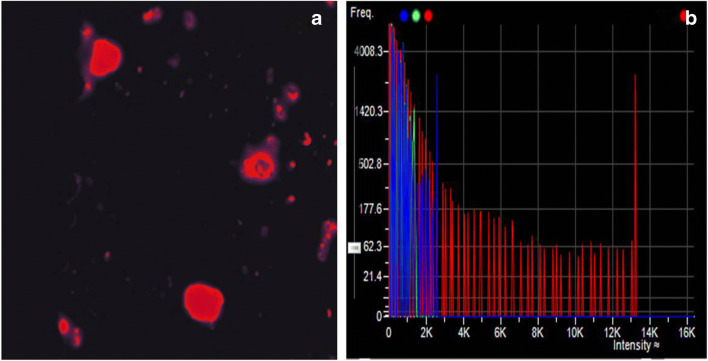

Fig. 2.

a shows cells emitting intense red fluorescence suggestive of malignant tumour cells at ×200 magnification. b Histogram of frequency (x-axis) versus intensity (y-axis) of a malignant tumour cell

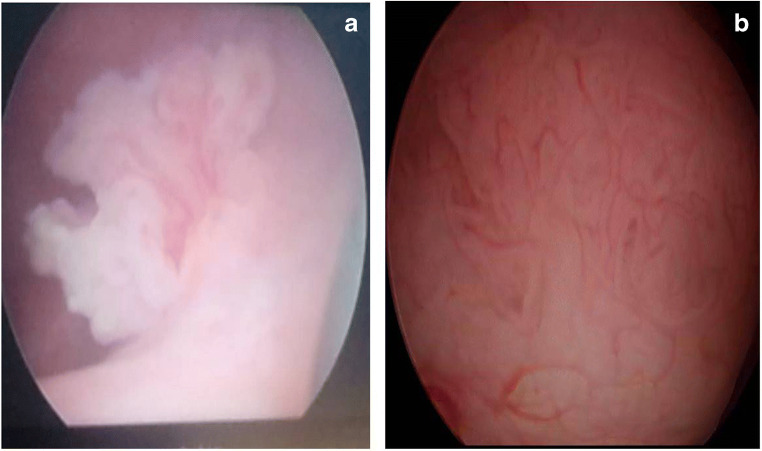

When histopathological results of the patients with bladder cancer were compared with conventional cytology and 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology, it was found out that latter was more sensitive and specific, more so in low-grade cancers. The sensitivity of conventional cytology was 61.19% in low grade cancers as compared to 75% in high-grade cancers, whereas the sensitivity was 100% with 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology both in low as well as high-grade cancers (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cystoscopic images of bladder tumours. a shows a papillary lesion. b shows a sessile lesion

Discussion

Bladder cancer is a common disease affecting both men and women. Its incidence ranks first among malignant cancers of the urinary system and second only to prostate cancer in the Western world. More than 90% of bladder cancers are of the transitional cell variety, 5% are squamous cell carcinomas, and less than 2% are adenocarcinomas.[14] At initial diagnosis of bladder cancer, 70 to 85% are non–muscle-invasive bladder cancers (NMIBC) and 15 to 30% are muscle-invasive bladder cancers (MIBC).[15] NMIBC is also known as superficial bladder cancer and includes pathological stages Ta (papillary), T1 (infiltration of lamina propria), and carcinoma in situ. Ta patients make up 70% of cases, T1 roughly 20% and carcinoma in situ about 10%. MIBC is commonly known as invasive bladder cancer and includes pathological stages T2, T3, and T4.[15, 16] Up to 80% of NMIBC patients relapse within 5 years; 30% of Ta patients progress to MIBC, while those with T1 and carcinoma in situ are more likely to develop MIBC.[1, 17] Statistically bladder cancer is associated with high incidence, progression, and recurrence rates.[18]

It is extremely important to accurately diagnose and assess patients with early bladder cancer and also to monitor high-risk postoperative bladder cancer patients on a regular basis (Table 3). Bladder cancer is commonly diagnosed using cystoscopy and biopsy, imaging methods, urinary cytology, fluorescence in situ hybridization, and urine protein detection.[1, 19] As of today, urinary cytology and cystoscopy/biopsy remain the gold standard examination tools to make a diagnosis of bladder cancer. Cystoscopy/biopsy is invasive and is associated with pain, bleeding, urinary tract infections and other complications. Moreover, it may be difficult for cystoscopy to detect tumours in secluded corners of the bladder, which restricts its clinical application. In comparison cytology is non-invasive, simple to use, inexpensive, and performs well, although it has low sensitivity and low diagnostic efficiency, especially with low-grade bladder cancer.[18]

Table 3.

Bladder cancer stage and grade

| No | Bladder cancer (n = 25) | Conventional cytology n (%) | 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology n (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stage pTa | 8(72.72) | 11(100) | 11 |

| 2 | pTis | 2(40) | 5(100) | 5 |

| 3 | pT1 | 3(60) | 5(100) | 5 |

| 4 | ≥pT2 | 3(75) | 4(100) | 4 |

| 5 | Low grade | 13(61.19) | 21(100) | 21 |

| 6 | High grade | 3(75) | 4(100) | 4 |

5-Aminolevulinic acid (ALA)-induced fluorescence cystoscopy has established itself in the detection of flat and/or small lesions that are barely visible under white-light cystoscopy.[20, 21] Fu et al.[22] investigated ex vivo urine fluorescence cytology as a biopsy-free means for detecting bladder cancers. Sediment of urine samples was extracted and incubated with a novel photosensitizer, hypericin. Laser confocal microscopy was used to capture the fluorescence images at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. Images were subsequently processed to single out the exfoliated bladder cancer cells from the other cells based on the cellular size. The study suggested that the fluorescence intensity profiles of hypericin in bladder cells could potentially provide an automated quantitative means of early bladder cancer diagnosis.

Pytel and Schmeller[23] investigated urinary cytology for induced fluorescence of urothelial cells and detected by fluorescence microscopy. The results were compared with the conventional cytologic and histologic findings. They detected ALA-induced fluorescence in 34 of 38 cases. One of the four histologically negative cases had a false-positive finding and 1 case of urothelial carcinoma did not show fluorescence. They concluded that fluorescence cytology was more sensitive than other non-invasive tests. Tauber et al.[24] evaluated as to whether tumour cells could be detected in bladder lavage fluid samples. Lavage sediments of all patients with histologically confirmed TCC bladder caused red fluorescence peaking at 635 nm, indicating protoporphyrin IX. The authors concluded that lavage sample sediments could be used to detect tumour associated red fluorescence in TCC of bladder.

Miyake et al.[25] used three different modalities of 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA)-based photodynamic diagnostic tests to diagnose bladder cancer. They developed a compact-size, desktop-type device quantifying red fluorescence in cell suspensions, named “Cellular Fluorescence Analysis Unit” (CFAU). Urine samples from 58 patients with bladder cancer were centrifuged, and urine sediments were then treated with ALA. ALA-treated sediments were subjected to three fluorescence detection assays, including the CFAU assay. The overall sensitivities of conventional cytology, fluorescence cytology, fluorescent spectrophotometric assay, and CFAU assay were 48%, 86%, 86%, and 87%, respectively. The three different ALA-based assays showed high sensitivity and specificity. The ALA-based assay detected low-grade and low-stage bladder urothelial cells at higher rate (68–80% sensitivity) than conventional urine cytology.

Yamamichi et al.[26] evaluated the diagnostic efficacy of 5-ALA-induced fluorescent urine cytology for urothelial carcinoma. They included 318 patients comprising 158 non-cancer patients, 84 bladder tumour patients, and 76 upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma patients. The sensitivity of 5-ALA-induced fluorescent urine cytology was significantly higher than that of conventional urine cytology (86.9% vs. 69.4%; p = 0.0002), and the specificity was equivalently high (96.2% vs. 95.6%; p = 1.0). In subgroup analysis, the high sensitivity of 5-ALA-induced fluorescent urine cytology was also detected regardless of age, sex, and tumour type. However, in terms of stage and grade, differences were only detected in patients with less than pTa stage (89.2% vs. 52.1%; p = 0.0001) and low-grade tumour (91.5% vs. 51.1%; p < 0.0001). The authors concluded that 5-ALA-induced fluorescent urine cytology was significantly more effective for urothelial carcinoma diagnosis when compared with the conventional cytology, especially in patients with low-stage and low-grade tumours.

All these abovementioned studies show that 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology is highly sensitive even in low-grade and low-stage tumours. These findings suggest that it might be possible to follow up using only 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology without cystoscopy in low- and intermediate-risk bladder tumours. Occasionally, false-positive findings of 5-ALA can be reported in conditions such as infection, inflammation, hyperplasia, and inexperience with the use of PDD.[27–29] 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology is associated with false negative reports whenever there is lack of cellular components in the voided urine specimen, or when cellular components including the cancer cells die out over the passage of time.

Conclusion

Our study shows that 5-ALA-induced fluorescent cytology is highly sensitive test to diagnose bladder cancer and shows a significant difference especially in low-grade bladder cancer when compared to conventional cytology. Our study has several limitations that include small sample size and single-center study. Our results need to be further validated in other cohorts so as to identify the high diagnostic efficacy of 5-ALA-induced fluorescent urine cytology for bladder cancer.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Babjuk M, Burger M, Zigeuner R, Shariat SF, van Rhijn B, Compérat E, Sylvester RJ, Kaasinen E, Böhle A, Palou Redorta J, Rouprêt M, European Association of Urology EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: update 2013. Eur Urol. 2013;64:639–653. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall MC, Chang SS, Dalbagni G, Pruthi RS, Seigne JD, Skinner EC, Wolf JS, Schellhammer PF. Guideline for the management of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (stages Ta, T1, and Tis): 2007 update. J Urol. 2007;178:2314–2330. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inoue K. 5-Aminolevulinic acid-mediated photodynamic therapy for bladder cancer. Int J Urol. 2017;24:97–101. doi: 10.1111/iju.13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik Z, Lugaci H. Destruction of erythroleukaemic cells by photoactivation of endogenous porphyrins. Br J Cancer. 1987;56:589–595. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinbach P, Weingandt H, Baumgartner R, Kriegmair M, Hofstadter F, Knuchel R. Cellular fluorescence of the endogenous photosensitizer protoporphyrin IX following exposure to 5-aminolevulinic acid. Photochem Photobiol. 1995;62:887–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1995.tb09152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishizuka M, Abe F, Sano Y, Takahashi K, Inoue K, Nakajima M, Kohda T, Komatsu N, Ogura SI, Tanaka T. Novel development of 5-aminolevurinic acid (ALA) in cancer diagnoses and therapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoue K, Takashi K, Kamada M, et al. Regulation of 5-aminolevulinic acid- mediated protoporphyrin IX-accumulation in human urothelial carcinomas. Pathobiology. 2009;76:303–314. doi: 10.1159/000245896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue K, Fukuhara H, Shimamoto T, Kamada M, Iiyama T, Miyamura M, Kurabayashi A, Furihata M, Tanimura M, Watanabe H, Shuin T. Comparison between intravesical and oral administration of 5-aminolevulinic acid in the clinical benefit of photodynamic diagnosis for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:1062–1074. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue K, Anai S, Fujimoto K, Hirao Y, Furuse H, Kai F, Ozono S, Hara T, Matsuyama H, Oyama M, Ueno M, Fukuhara H, Narukawa M, Shuin T. Oral 5-aminolevulinic acid mediated photodynamic diagnosis using fluorescence cystoscopy for non- muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a randomized, double-blind, multicentre phase II/III study. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2015;12:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue K, Matsuyama H, Fujimoto K, Hirao Y, Watanabe H, Ozono S, Oyama M, Ueno M, Sugimura Y, Shiina H, Mimata H, Azuma H, Nagase Y, Matsubara A, Ito YM, Shuin T. The clinical trial on the safety and effectiveness of the photodynamic diagnosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer using fluorescent light–guided cystoscopy after oral administration of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2016;13:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kriegmair M, Baumgartner R, Knuechel R, et al. Fluorescence photodetection of neoplastic urothelial lesions following intravesical instillation of 5-aminolevulinic acid. Urology. 1994;44:836–841. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(94)80167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krammer B, Plaetzer K. ALA and its clinical impact, from bench to bedside. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2008;7:283–289. doi: 10.1039/B712847A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakai Y, Anai S, Onishi S, Masaomi K, Tatsumi Y, Miyake M, Chihara Y, Tanaka N, Hirao Y, Fujimoto K. Protoporphyrin IX induced by 5-aminolevulinic acid in bladder cancer cells in voided urine can be extracorporeally quantified using a spectrophotometer. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2015;12:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YS, Maruvada P, Milner JA. Metabolomics in biomarker discovery: future uses for cancer prevention. Future Oncol. 2008;4:93–102. doi: 10.2217/14796694.4.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witjes JA, Compérat E, Cowan NC, De Santis M, Gakis G, Lebret T, et al. EAU Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer: Summary of the 2013 Guidelines. Eur Urol. 2014;65:778–792. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burger M, Catto JW, Dalbagni G, Grossman HB, Herr H, Karakiewicz P, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of urothelial bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2013;63:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowles MA, Hurst CD. Molecular biology of bladder cancer: new insights into pathogenesis and clinical diversity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:25–41. doi: 10.1038/nrc3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu CZ, Ting HN, Ng KH, Ong TA. A review on the accuracy of bladder cancer detection methods. J Cancer. 2019;10:4038–4044. doi: 10.7150/jca.28989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye F, Wang L, Castillo-Martin M, McBride R, Galsky MD, Zhu J, et al. Biomarkers for bladder cancer management: present and future. American journal of clinical and experimental urology. 2014;2:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rink M, Babjuk M, Catto JW, et al. Hexyl aminolevulinate-guided fluorescence cystoscopy in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a critical review of the current literature. Eur Urol. 2013;64:624–638. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burger M, Grossman HB, Droller M, Schmidbauer J, Hermann G, Drăgoescu O, Ray E, Fradet Y, Karl A, Burgués JP, Witjes JA, Stenzl A, Jichlinski P, Jocham D. Photodynamic diagnosis of non- muscle-invasive bladder cancer with hexaminolevulinate cystoscopy: a meta-analysis of detection and recurrence based on raw data. Eur Urol. 2013;64:846–854. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu CY, Ng BK, Razul SG, Chin WWL, Tan PH, Lau WK, Olivo M. Fluorescence detection of bladder cancer using urine cytology. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:525–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pytel A, Schmeller N. New aspect of photodynamic diagnosis of bladder tumors: fluorescence cytology. Urology. 2002;59:216–219. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(01)01528-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tauber S, Stepp H, Meier R, Bone A, et al. Integral spectrophotometric analysis of 5-aminolaevulinic acid-induced fluorescence cytology of the urinary bladder. BJU Int. 2006;97:992–996. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyake M, Nakai Y, Anai S, Tatsumi Y, Kuwada M, Onishi S, Chihara Y, Tanaka N, Hirao Y, Fujimoto K. Diagnostic approach for cancer cells in urine sediments by 5-aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic detection in bladder cancer. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:616–622. doi: 10.1111/cas.12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamichi G, Nakata W, Tani M, Tsujimura G, Tsujimoto Y, Nin M, Mimura A, Miwa H, Tsujihata M. High diagnostic efficacy of 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced fluorescent urine cytology for urothelial carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24(9):1075–1080. doi: 10.1007/s10147-019-01447-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nerli RB, Rangrez Shadab, Bidi R. Saziya, Ghagane shridhar C. and Chandra Shreya. Urinary cytology in the diagnosis of bladder cancer. Accepted in International Journal of Cancer Science & Therapy. 2020

- 28.Nakai Y, Ozawa T, Mizuno F, Onishi S, Owari T, Hori S, Morizawa Y, Tatsumi Y, Miyake M, Tanaka N, Tsuruta D, Fujimoto K. Spectrophotometric photodynamic detection involving extracorporeal treatment with hexaminolevulinate for bladder cancer cells in voided urine. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:2309–2316. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2476-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiess PE, Grossman HB. Fluorescence cystoscopy: is it ready for use in routine clinical practice? Curr Opin Urol. 2006;16:372–376. doi: 10.1097/01.mou.0000240312.16324.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]