Case Report

A 63-year-old gentleman presented with a history of fever and weight loss for 6 months and nonproductive cough for 3 months. There was no history of hypertension, heart disease, TB, or asthma. On examination, he had decreased breath sound on right mid zone. His neurological and musculoskeletal examination was normal and he did not have any lymphadenopathy. An initial chest radiograph showed an anterior mediastinal mass extending to the right of the ascending aorta. A contrast computed tomographic (CT) scan showed a lobulated 15×12cm heterogeneous soft tissue mass in the anterior mediastinum. There were no areas of the chest wall or pericardial invasion or lymphadenopathy (Fig. 1). Whole-body PET-CT showed FDG avid, heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue mass lesion measuring ~10.1 × 7.1 × 11.8 cm in the anterior mediastinum, displacing and compressing anterior segment of the right upper lobe and medial segment of the right middle lobe. No other FDG avid lesion in the body was seen.

Fig. 1.

Heterogeneous soft tissue mass in the anterior mediastinum

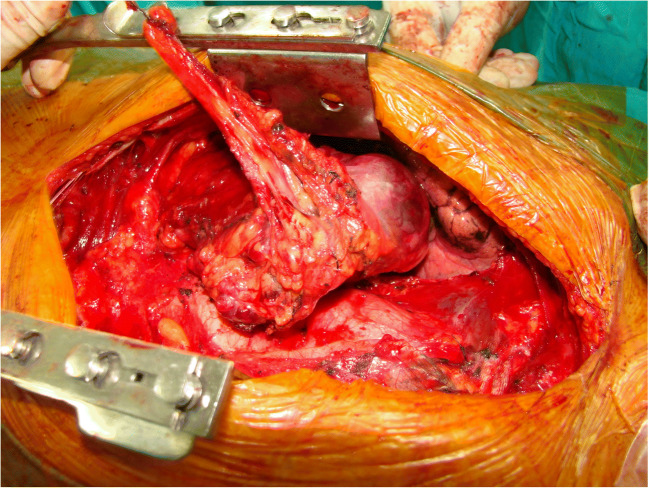

The patient had undergone a CT-guided biopsy which revealed thymoma. IHC on tumor cells were marked by broad spectrum CK. CD20 was not expressed. Ki-67 of the tumor cell population inclusive of lymphocytes/epithelial cells was 60%, opined lymphocyte-rich thymoma. The patient was submitted to median thoracotomy to remove a large mass occupying the upper and anterior mediastinum in position beside the pericardium from just right to the superior vena cava and right atrium, extending laterally and distally in the direction of the diaphragm (Fig. 2). The tumor was well encapsulated and no significant lymphadenopathy was seen. Post-op. histopathology revealed single lobulated soft tissue mass measures 13.5 × 9.5 × 5.5 cm with attached fibro-fatty tissue on the surface. Microscopic examination revealed lobulated tumor with fibrous bands separating nodules composed of sheets, fascicles, and whorls of plump to spindle-shaped cells having bland, vesicular nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and moderate to abundant cytoplasm along with a patchy, dense infiltrate of small lymphoid cells. An occasional mitotic figure is seen. No necrosis or capsular invasion is seen. Features were compatible with a mixed thymoma.

Fig. 2.

Intra-operative: large mediastinal mass. Resection in continuation

Post-operatively, the patient developed respiratory difficulty with collapse of the right lower lobe for which he was put on a ventilator, and also bronchoscopy and broncho-alveolar lavage was done.

Electroneuromyography (ENMG) was normal, repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) test revealed neuromuscular junction dysfunction, his serum antiacetylcholinestrase receptor antibody level was 8.26 nmol/L (normal range being <0.3 nmol/L). Based on radiological, biochemical, and pathological findings, a diagnosis of thymoma (World Health Organization classification type AB and Masaoka classification stage I) associated with myasthenia gravis was made. Post-operatively, pyridostigmine 60 mg 3 times a day and prednisolone 40 mg once daily were started and the patient was discharged in a satisfactory condition.

Discussion

ThQueryymomas are slow-growing tumors that generally are benign. Radiographically, thymomas are usually well circumscribed, round, or oval structures, with well-defined margins and may have some peripheral calcification. The World Health Organization has developed a classification system (Table 1), but most of the clinicians follow the general principles outlined by the Masaoka classification (Table 2) [1].

Table 1.

WHO classification

| Type | Histologic description |

|---|---|

| A | Medullary thymoma |

| AB | Mixed thymoma |

| B1 | Predominently cortical thymoma |

| B2 | Cortical thymoma |

| B3 | Well-differentiated thymic carcinoma |

| C | Thymic carcinoma |

Table 2.

Masaoka classification (survival%)

| Stage I | Encapsulated tumor with no gross or microscopic invasion (96%) |

| Stage II | Macroscopic invasion into the mediastinal fat or pleura or microscopic invasion into the capsule (86%) |

| Stage III | Microscopic invasion of the pericardium, great vessels, or lung (69%) |

| Stage IVa | Pleural or pericardial dissemination (50%) |

| Stage IVb | Lymphogenous or hematogenous metastases |

A wide variety of systemic disorders may be associated in up to 71% of patients with thymoma, including myasthenia gravis (MG), SLE, polymyositis, myocarditis, Sjogren syndrome, ulcerative colitis, Hashimoto thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, and scleroderma. MG is the most common disorder associated with thymoma occurring in 30% to 50% of patients and approximately 15% of patients with myasthenia gravis have thymic tumors. MG is a disorder of neuromuscular transmission. Clinical features are diplopia, ptosis, dysphagia, and fatigue which started slowly and result from the production of the antibodies to the post-synaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR) at myoneural junction. Ocular symptoms are the most common initial complaints, eventually progressing to generalized weakness in 80%. The role of thymus in myasthenia gravis is unclear, it may have a role in autosensitization of T lymphocytes to acetylcholine receptor proteins or an unknown action of thymic hormone. AChR antibodies are the main cause of muscle weakness in thymoma MG [2]. Additional non-AChR muscle autoantibodies reacting with striated muscle TITIN and RyR (RYANODINE receptor) antigens are found in up to 95% of MG patients with thymoma and in 50% of late-onset MG patients (MG onset at age of 50 years or later) [3]. These antibodies are usually associated with more severe MG [4]. Striational antibodies demonstrated in immunofluorescence are largely made up of titin antibodies [5].

Surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment, and it should be ensured to radically remove the neoplasm. Thymectomy can be performed through trans-sternal route or through a video-assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) approach, almost with the same outcome [6]. Radical excision of a thymoma cures the thymic tumor in most of the cases, but patients may continue to suffer from MG after thymectomy. It emphasizes the continuous follow-up and pharmacological treatment. When the thymoma invades the pleura or the pericardium, radical excision will not be possible and further oncological treatment is necessary. Presurgery plasmapheresis or intravenous infusion of immunoglobulin (IV-IgG) removes a great deal of circulating pathogenic antibodies [7] in all patients with thymoma and MG prior to thymectomy, to minimize the risk of post-thymectomy MG exacerbation and myasthenic crisis. This practice varies and depends upon the institution, and there is no consensus on this issue. IV-IgG should be considered as first choice in patients at high risk of developing cardiopulmonary failure secondary to fluid overload caused by plasmapheresis. MG outcome after thymectomy is generally less favorable in patients older than 45 years as in our case (i.e., mostly late-onset and thymoma MG patients) [8].

Plasmapheresis and immunoglobulin treatments are also indicated in severe cases of thymoma MG regardless of thymectomy, such as in MG crisis and in severe MG cases with poor response to standard pharmacological treatment [9]. The first pharmacological choice in the treatment of thymoma MG is acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. The second choice is immunosuppressive drugs whenever additional pharmacological treatment is needed before or after thymectomy. Several immunosuppressive drugs are available, such as corticosteroids, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, and tacrolimus. Steroids such as prednisolone are frequently given on alternate days, by gradually raising the dose to 60–80 mg initially and then slowly tapering to 20 mg or lower. If long-term treatment with steroids is regarded necessary, nonsteroid immune-suppressants such as azathioprine should be introduced in addition (usually 100–150 mg a day). While the steroid effect appears rapidly, the clinical effect of other immunosuppressants may take a few weeks to several months to develop [10]. Overall, about 80% of MG patients and 95% of thymoma MG patients need immunosuppressive drug treatment for more than 1 year [11].

Tacrolimus, which is an immunosuppressant and enhancer of RyR-related sarcoplasmic calcium release, may be especially beneficial in MG patients with RyR antibodies that in theory might block the RyR interfering with its function. Since most patients with thymoma MG have RyR antibodies, tacrolimus may act specifically in these patients. It may have a purely symptomatic effect in addition to its immunosuppressive impact [8]. Tacrolimus has demonstrated favorable effects in the treatment of MG, both as monotherapy and as an add-on to prednisolone [12]. Patients should undergo a thorough cardio-logical investigation prior to commencing tacrolimus treatment.

Long-term observation of thymoma MG and age-matched non-thymoma MG patients showed no difference in MG severity over time, and both groups improved to the same degree after MG diagnosis as a result of pharmacological treatment and thymectomy. The need for immunosuppressive treatment in the two groups was similarly high. A thymoma that has been completely removed surgically does not necessarily mean a worse MG prognosis in thymoma MG [13].

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Gyanendra Swaroop Mittal, Email: g20mittal@gmail.com.

B. Niranjan Naik, Email: bniranjan29@gmail.com.

Deepak Sundriyal, Email: drdeepaksundriyal@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Masaoka A, Monden Y, Nakahara K, Tanioka T. Following study of thymoma with special reference to their clinical stages. Cancer. 1981;48:2485–2492. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811201)48:11<2485::AID-CNCR2820481123>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindstrom JM. Acetylcholine receptors and myasthenia. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:453–477. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(200004)23:4<453::AID-MUS3>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aarli JA. Late-onset myasthenia gravis: a changing scene. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:25–27. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skeie GO, Mygland A, Aarli JA, Gilhus NE. Titin antibodies in patients with late onset myasthenia gravis: clinical correlations. Autoimmunity. 1995;20:99–104. doi: 10.3109/08916939509001933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romi F, Skeie GO, Gilhus NE, Aarli JA. Striational antibodies in myasthenia gravis: reactivity and possible clinical significance. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:442–446. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zahid I, Sharif S, Routledge T, Scarci M. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or trans-sternal thymectomy in the treatment of myasthenia gravis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12:40–46. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.251041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gajdos P, Chevret S, Toyka K. Plasma exchange for myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;4:Article ID CD002275. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venuta F, Rendina EA, Giacomo TD, et al. Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: a 27-year experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:621–625. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(99)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richman DP, Agius MA. Treatment of autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 2003;61:1652–1661. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000098887.24618.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romi F, Gilhus NE, Aarli JA. Myasthenia gravis: clinical, immunological, and therapeutic advances. Acta Neurol Scand. 2005;111:134–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders DB, Evoli A. Immunosuppressive therapies in myasthenia gravis. Autoimmunity. 2010;43:428–435. doi: 10.3109/08916930903518107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konishi T, Yoshiyama Y, Takamori M, Yagi K, Mukai E, Saida T, The Japanese FK506 MG Study Group Clinical study of FK506 in patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:570–574. doi: 10.1002/mus.10472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romi F, Gilhus NE, Varhaug JE, Myking A, Aarli JA. Disease severity and outcome in thymoma myasthenia gravis: a long-term observation study. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:701–706. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]