Abstract

Aims:

We explored the relationship between objective and subjective measures of burden prior to and after a telehealth-based caregiver intervention. One caregiver participated in two studies, one to assess the feasibility of objective, home-based monitoring (EVALUATE-AD), the second to assess the feasibility of a caregiver education telehealth-based intervention, Tele-STAR.

Methods:

Subjective measures of burden and depression in Tele-STAR and objective measures related to daily activities of the caregiver in EVALUATE-AD were compared to examine trends between the different outcome measures.

Results:

While the caregiver reported an increase in distressing behaviors by her partner, burden levels did not significantly change during or after the Tele-STAR intervention, while objective measures of activity and sleep showed a slight decline.

Conclusion:

Unobtrusive home-based monitoring may provide a novel, objective method to assess the effectiveness of caregiver intervention programs.

Keywords: Caregiver burden

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is one of the most emotionally and financially expensive diseases in America, due to the high prevalence and high care needs [1, 2]. Most of this cost is borne by family caregivers, and the demands on them will grow as the number of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) increases [3]. ADRD caregiving is particularly challenging because as individuals with dementia experience memory loss and changes in their behavior, caregivers report increased depression and “burden” [2, 4-6]. Thus, researchers strive to develop interventions that reduce this burden.

Numerous studies have employed interventions to reduce caregiver burden and depression [7]. The majority of caregiver instruments employed in these studies rely on self-reported scales assessing subjective aspects of caregiving to determine the level of caregiver burden experienced [8, 9]. However, subjective point-in-time assessments are prone to recall bias [10, 11], social desirability bias [12] and recency effects [13]. Additionally, studies of physical activity [14], medication adherence [15] and health service utilization [16] show disagreements between self-report assessment tools and objective measurements. Due to these limitations, an assessment method that unobtrusively and objectively measures activity and effort related to caregiving could improve the assessment of caregiver burden and complement subjective caregiver tools.

Home-based, pervasive sensing and computing systems provide a novel method to capture data on metrics related to everyday physical and cognitive function [17]. The EVALUATE-AD (Ecologically Valid, Ambient, Longitudinal and Unbiased Assessment of Treatment Efficacy in Alzheimer’s Disease) study is an observational proof-of-concept trial examining the feasibility of using an unobtrusive home-based monitoring system to detect the effects of initiating or discontinuing standard dementia treatments. One component of this study is to examine the ability of this system to continuously collect data on objective outcomes related to caregiving. Here we present preliminary data on conventional subjective caregiver assessment methods and objective sensor-based measures from a caregiver who simultaneously participated in EVALUATE-AD and a telehealth intervention study (Tele-STAR).

Methods

The Studies

EVALUATE-AD Caregiver Study

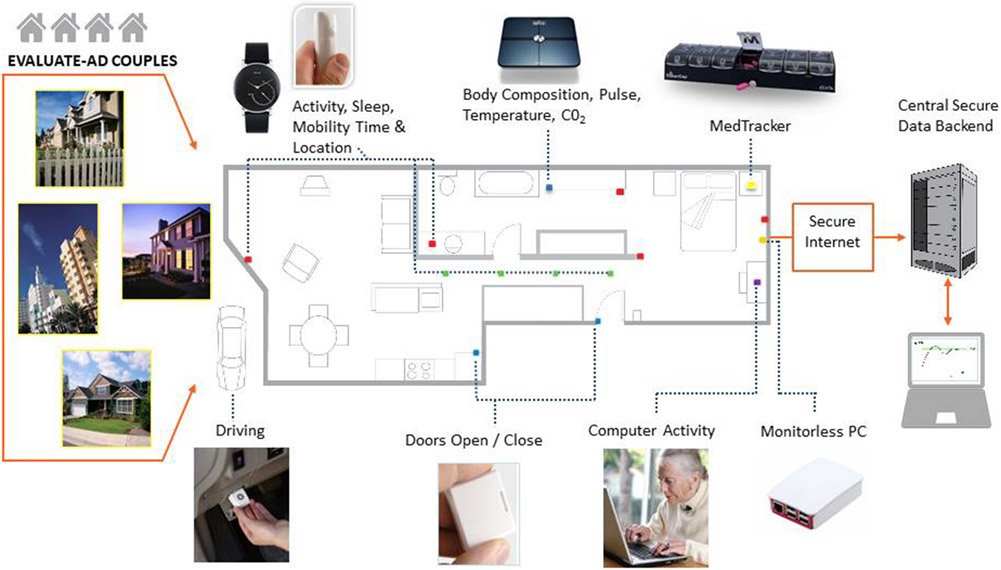

The caregiver pilot project within the EVALUATE-AD trial was designed to assess the feasibility of collecting data related to time and effort spent on caregiving activities using a home-based pervasive sensing and computing system and to compare the objective sensor-based measures to conventional clinical measures of caregiver behavior and burden. The ORCATECH (Oregon Roybal Center for Aging and Technology) home-based computing system (Fig. 1) is deployed in the homes of participants for 12–18 months, using established protocols [17, 18]. All data collection from installed sensors occurs wirelessly through a monitor-less PC without the need for participant involvement. Infrared motion sensors (NYCE Control) placed on the wall collect data on activity, location and room transitions. An activity-monitoring wristwatch (Withings Steel; https://www.withings.com/us/en/steel) detects daily step count and total sleep time. Time spent out of the home is determined using data from contact sensors on external doors. At the baseline EVALUATE-AD visit, family caregivers complete assessments at home and then via online versions of the questionnaires sent every 3 months during the study (Table 1). In addition, an online weekly self-report survey is sent via e-mail to caregivers and asks about internal states, such as mood, pain level and loneliness, which can only be determined by self-report.

Fig. 1.

Components of the home-based computing and sensing platform.

Table 1.

EVALUATE-AD caregiver study assessments and sensor-derived measures

| Week | 0 | 13 | 26 | 39 | 52 | 65 | 78 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit type: | Screening visit |

Online | Online | Online | Month 12 |

Online | Month 18 |

| Consent | X | ||||||

| Personal & Family History Questionnaire | X | X | X | ||||

| MMSE | X | X | X | ||||

| ISAAC Technology Use Survey | X | X | X | ||||

| Technology & Computer Experience and Proficiency Questionnaires | X | X | |||||

| Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form (GDS-SF) | X | X | X | ||||

| Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Assessment (PSQA) | X | X | X | ||||

| ORCATECH Health & Life Activity Form On-line self-report: ER, doctor, hospital visits, home visitors, mood, pain, loneliness, falls, injuries, change in home space, home assistance received, change in medications | Weekly for duration of study | ||||||

| Caregiving: Time out of home/Time alone in home/Time in same room with partner/Time apart in different rooms | Assessed continuously | ||||||

| Physical capacity/Mobility: Total daily activity/Mobility/Step count/Walking speed/Time in different rooms | Assessed continuously | ||||||

| Sleep: Time up/Time in Bed/Times Up at Night/Sleep Latency/Sleep Duration | Assessed daily | ||||||

| Cognitive functions: Time to complete on-line tasks (e.g., weekly online self-report survey), number of computer sessions | Assessed continuously | ||||||

| Physiologic Health: Daily BMI, pulse | Assessed daily | ||||||

Tele-STAR

The Tele-STAR study translated an evidence-based intervention (STAR-C [19]) from an in-person intervention into a telehealth intervention. The feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of the telehealth-based intervention were examined. Tele-STAR participants met with consultants via a secure videoconferencing link [20] to address care-recipient behaviors that they found upsetting. Using a cognitive behavioral approach, caregivers identified triggers to the behaviors and strategies to address the behaviors. After completing the required 8 sessions, caregivers met with each other in groups of three (Tele-STAR trios). They were offered the opportunity to contact each other after study completion. Burden and depression were measured with classic measures (the 4-item Zarit Burden Interview [21], the Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist [22] and the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale [23]) prior to, during and after the intervention.

Analysis

For Tele-STAR, pre-post changes were measured using paired t tests [24]. Qualitative data were gathered from two focus groups and analyzed using a phenomenological approach [25]. In the EVALUATE-AD pilot, outcome measures from the sensor-based data in Table 1 are being investigated for their ability to predict subjective caregiver burden levels. To measure activity level, step count is taken directly from the daily total calculated by the wristwatch. Total sleep time is calculated as the onset of the first sleep stage to the end of the last sleep stage detected by the wristwatch over one night. Time spent together in the same room is calculated from the infrared wall-mounted sensors. We compared quantitative findings from the subjective and objective measures in this one participant case study.

Results

Case

The participants were a 71-year-old female caregiver and her 74-year-old spouse with AD. At study entry to EVALUATE-AD, the participant with AD had a Mini Mental State Examination [26] score of 17, Clinical Dementia Rating [27] score of 1, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire [28] score of 6 and Functional Activities Questionnaire [29] score of 22. The caregiver verbally agreed to participate in the case study, which was approved by the IRB (OHSU IRB #18066).

At Tele-STAR study entry, the caregiver reported she had 18 years of education and had actively been providing care for her spouse for 1.5 years, with an average of 106 h/week. At baseline, her depression scores were within normal limits [23], but burden scores were on the moderately high side at 19 [21, 22]. The caregiver rated the care recipient’s overall quality of life as “good” but relational and financial concerns were noted.

EVALUATE-AD Study

Acceptance of the technology and home-based system was high in this participant. She completed 96.8% of her weekly health surveys. On her exit survey, she strongly agreed with the statements “I do not mind being monitored unobtrusively in my home” and “I did not find the sensor system interfered with activities related to caregiving.” She did not express any privacy concerns related to the use of monitoring technology in the study.

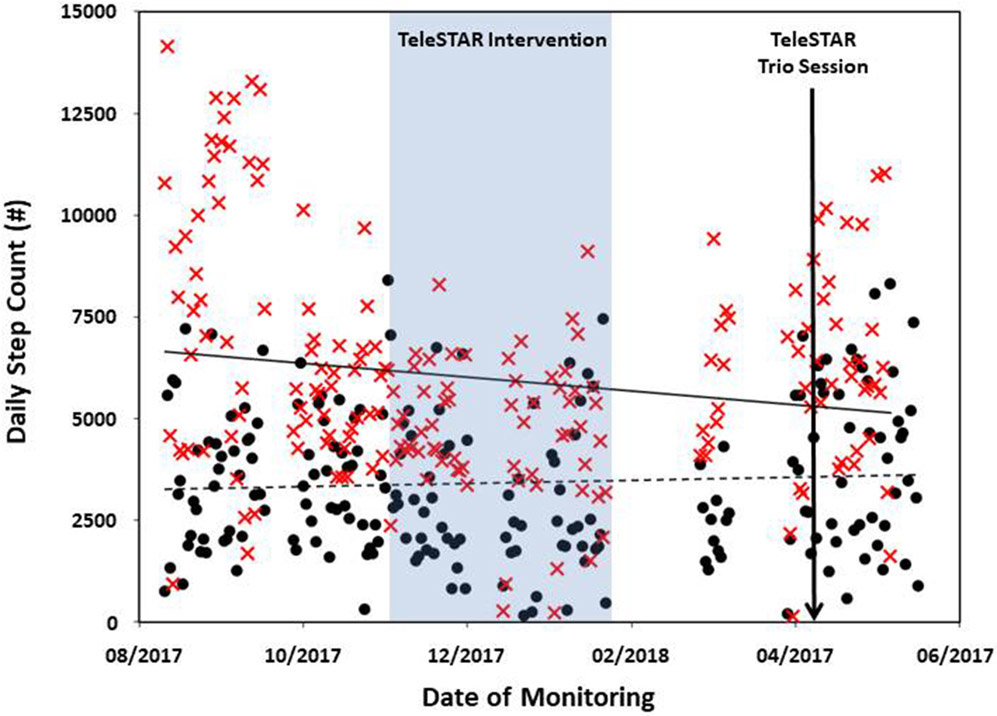

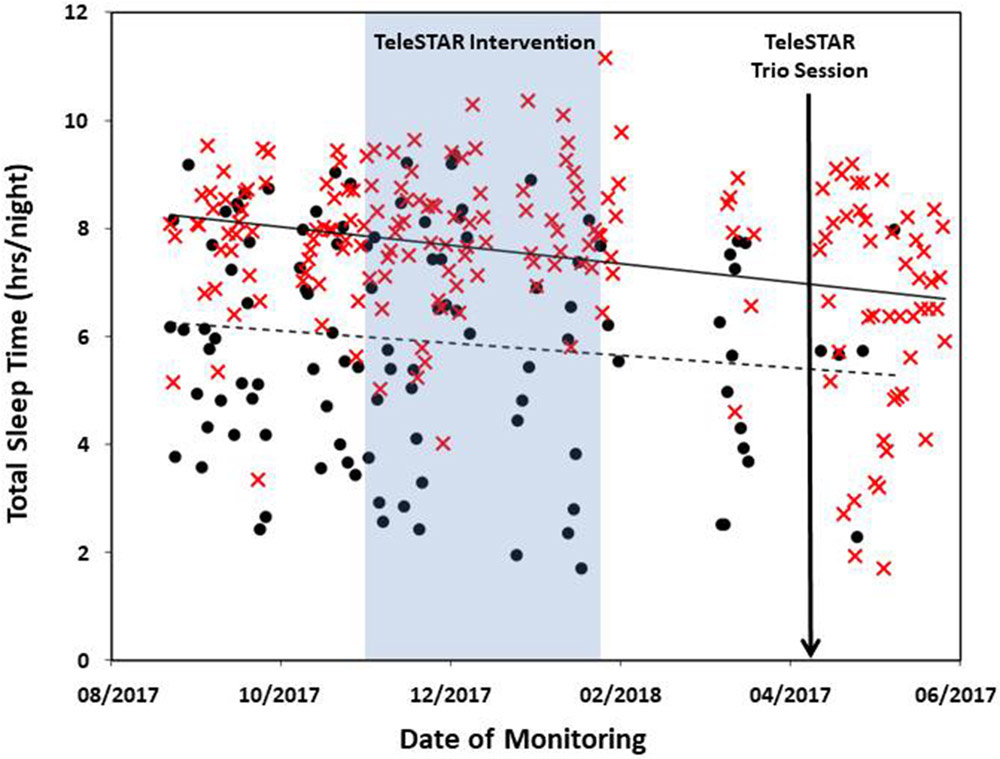

The couple was enrolled in the study for 313 days. Daily step count was available for 194 days for the caregiver and 205 days in her partner with AD. The mean daily step count was 5,973 (SD 2,709) for the caregiver and 3,425 (SD 1,836) for her partner. Total sleep time was available for 187 days for the caregiver and 109 days for her partner with mean total sleep times of 7.5 h (SD 1.6) and 5.9 h (SD 2.0), respectively. Missing data were due to two factors: (1) technical issues with the data collection system resulted in the data not being collected from the watches during two time periods (50 days approx.); (2) no data collection occurred on the days when the watch was not worn, and the lower number of nights collected from the person with AD was due to noncompliance with wearing the watch at night. The caregiver’s daily step counts (Fig. 2) and total sleep times (Fig. 3) decreased slightly during the monitoring period. Her self-reported levels of burden remained fairly stable during this period (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Daily total number of steps during their enrolment in EVALUATE-AD for the caregiver (red X) and her partner with AD (black circles). Daily step count is taken directly from the daily total calculated by the Withings Steel wristwatch.

Fig. 3.

Total sleep time for each night during their enrolment in EVALUATE-AD for the caregiver (red X) and her partner with AD (black circles). Total sleep time is calculated from sleep data collected by the Withings Steel wristwatch.

Table 2.

Subjective outcome measures from EVALUATE-AD caregiver study and Tele-STAR

| Outcome Measure | Outcome Measure Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVALUATE-AD | 7/17/2017 | 10/18/2017 | 1/24/2018 | 4/18/2018 |

| FAQ | 22 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| NPI | 6 | 7 | 12 | 8 |

| ZBI-12 | 19 | 20 | 23 | 20 |

| TeleSTAR | 11/8/2017 | 12/17/2017 | 1/24/2018 | 4/9/2018 |

| RMBPC Reactivity | 18 | 17 | 26 | |

| ZBI-4 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| CESD | 9 | 4 | 8 | 4 |

FAQ, Functional Activities Questionnaire; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; ZBI-12, Zarit Burden Interview, 12 items; RMBPC, Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist; ZBI-4, Zarit Burden Interview, 4 items; CESD, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression.

Tele-STAR Study

The caregiver completed all 8 Tele-STAR sessions as well as her assigned homework. She also engaged in the trio session. Prior to the intervention, the caregiver reported three behaviors which she found “very much” distressing [22]. In the Tele-STAR sessions, she addressed these, including her partner’s night time activity. This night time behavior centered on his need to get ready for a work interview, in which he would look anxiously for his clothing and work documents, telling his spouse, “You don’t understand, I need to be there … I can’t blow it this time.”

At the conclusion of the intervention, the frequency of her partner’s distressing behaviors increased, but her reactivity to them did not. Two months post intervention, the behaviors, and the caregiver’s response to them, increased. There was a slight improvement in her depression scores after the first four Tele-STAR sessions, but depression scores returned to baseline after the intervention. Taken together, the data suggest that while the frequency of the care recipient’s behaviors increased, her reaction to them (how upsetting they were for her) held steady throughout the intervention. Once the intervention ended, however, the behaviors became more frequent and more upsetting. After the intervention, the caregiver began the process of placing her spouse into long-term care.

In comparing the objective and subjective data, we see a trend of decreasing step counts as the frequency of care recipient behaviors increased. The time the caregiver and her spouse were together, and the caregiver’s daily activities, suggests the potential for higher caregiver burden. Objective measures of sleep also show a trend in decreasing total sleep times as her partner’s night time behavior increased, and as she found these behaviors more upsetting. In the time immediately before the AD participant’s transition to a higher level of care, there were a number of nights where the caregiver had very little sleep. Across the board, there was little effect of the Tele-STAR intervention for this caregiver’s burden and depression, as measured with objective and subjective assessments. However, it is impossible to know whether the intervention stabilized the burden (it may have been worse without the intervention). More work is needed to understand how to measure the effect of an intervention on caregiver burden and depression using both the traditional and novel modalities used in this study.

Discussion/Conclusion

This report highlights a novel method to collect objective measures related to caregiver activities and how this could be combined with an intervention aimed at reducing caregiver burden. Multiple health and functional outcome measures, including activity level and sleep behavior were monitored longitudinally in both a caregiver and her spouse with AD. These measures were collected unobtrusively. The validated objective outcome measures have the potential to quantifiably measure changes in time and effort spent on caregiving activities that may occur as the result of an intervention such as Tele-STAR. A composite group of objective measures found to be correlated with subjective measures of caregiver burden could provide evidence of effectiveness in a caregiver intervention study. This approach could increase the precision to detect changes and has previously been used to improve the prediction of a transition to higher levels of care in individuals with cognitive impairment [30].

There are multiple potential benefits to using home-based monitoring. The continuous and high-frequency data collection where multiple data points are collected daily provides the ability to detect subtle changes over time, allowing for more precise assessments. The assessments are longitudinal and constant. Systems could be installed prior to an intervention to determine a baseline of caregiving activities. During an intervention, reductions in objective caregiver activities that correlate with higher levels of burden would help determine mechanisms of action and effectiveness. Additionally, any sustained benefits of the intervention could be assessed for months afterward.

The technology employed in the system is ambient and unobtrusive and therefore less likely to contribute additional caregiver stress or burden. It could decrease the need for caregivers to complete extensive self-report surveys that can be time-consuming. Caregiver tools that can provide more frequent and longitudinal assessments, such as caregiver diaries, can be subject to respondent fatigue over longer periods and an extra source of stress for some caregivers [31]. Further, unobtrusive monitoring removes reliance on caregivers to return surveys. Response rates to mailed surveys, and efforts to encourage return are time consuming and expensive [32]. Unobtrusive monitoring eliminates challenges associated with response rates.

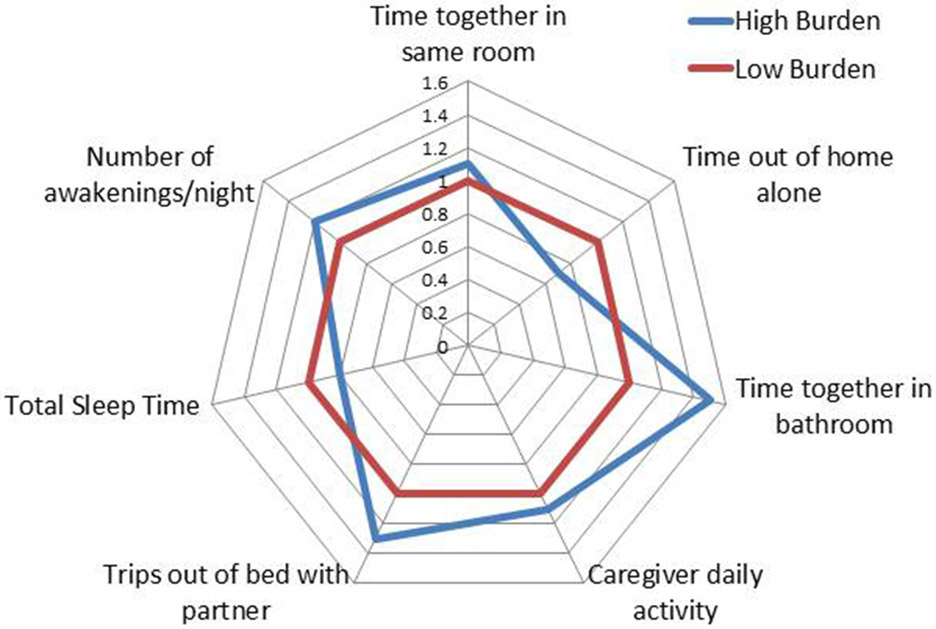

The EVALUATE-AD and Tele-STAR projects highlight the potential for using technology (home-based sensors and telehealth) to reach populations that are traditionally less able to participate in research studies. Taking the data collection and intervention to the participant’s home could be especially beneficial for caregivers of individuals with ADRD, whose caregiver duties and higher levels of burden can impair their ability to attend frequent study visits. These methods could also facilitate participation of individuals in more remote areas that are not within close travel distance to a research facility [33]. Currently, the development of objective measures of time and effort related to caregiving tasks is in the pilot stage. Data from the EVALUATE-AD study will provide information on the feasibility of collecting these measures and information on which measures best predict subjective caregiver burden. Comparison of continuous measures to self-reported questionnaires will be performed using a method described in previous studies [34, 35]. The goal is to create a multidomain model of time and effort spent on caregiving activities that differentiates between high and low levels of caregiver burden (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Composite model of digital biomarkers showing potential domains associated with the degree of caregiver burden. Values in the figure represent odds ratios, with low burden values normalized to 1.0.

Home-based monitoring systems in caregiver research also have potential limitations. The deployment of these systems requires acceptance of installing technology in the home and compliance with wearing an activity-monitoring wristwatch. Individuals may be hesitant to participate due to privacy and security concerns. However, focus group research indicates that these concerns are secondary to the desire to maintain independence and health, and are less of a concern if proper security measures are in place [36]. Participants need to have a reliable, broadband Internet connection for transmission of the data, which is less common in rural areas. Finally, technical issues related to data collection can arise using an ambient computing system. This requires that systems have methods to inform the research team when sensors fail, or data collection does not occur as expected, to ensure any issues are quickly corrected to avoid loss of data.

In summary, our case study reveals that there is potential to evaluate the effect of an intervention on caregiver burden using ambient home monitoring. While we do not suggest that objective caregiver outcome measures would completely replace subjective measures, their addition could improve the precision of detecting changes in caregiving activities and burden. Future work is needed to assess how these two assessment methods can complement each other to better predict the effectiveness of new interventions.

Acknowledgment

We express our gratitude to the family who graciously let us into their homes to advance caregiving science.

Funding Sources

NIA P30AG008017; P30AG024978, Merck Investigators Study Program, The Collins Medical Trust.

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Thomas has no conflicts of interest to declare. He receives research support from the NIH (P30 AG024978). Dr. Lindauer has no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Kaye receives research support from the NIH (P30 AG008017, R01 AG024059, P30 AG024978, P01 AG043362, U01 AG010483), directs a center that receives research support from the NIH, CDC, Nestle Institute of Health Sciences, Roche, Lundbeck, Merck and Eisai, is compensated for serving on Data Safety Monitoring Committees for Eli Lilly and Suven, receives reimbursement through Medicare or commercial insurance plans for providing clinical assessment and care for patients, serves as an unpaid Chair of the International Society to Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment for the National Alzheimer’s Association and as an unpaid Commissioner for the Center for Aging Services and Technologies, and serves on the editorial advisory board of the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia and as Associate Editor.

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics

The subjects consented to participate in this case report and have given their written informed consent for the EVALUATE-AD and TeleSTAR studies. The study protocol has been approved by the research institute’s committee on human research (IRB #18066).

References

- 1.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013. April;368(14):1326–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Ann Intern Med. 2015. November;163(10):729–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer’s Association. 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016. April;12(4):459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fonareva I, Oken BS. Physiological and functional consequences of caregiving for relatives with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014. May;26(5):725–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Bookwala J, Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: prevalence, correlates, and causes. Gerontologist. 1995. December;35(6):771–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindauer A, Harvath TA. The meanings caregivers ascribe to dementia-related changes in care recipients: a meta-ethnography. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2015. Jan-Feb;8(1):39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandepitte S, Van Den Noortgate N, Putman K, Verhaeghe S, Annemans L. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an in-home respite care program in supporting informal caregivers of people with dementia: design of a comparative study. BMC Geriatr. 2016. December;16(1):207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deeken JF, Taylor KL, Mangan P, Yabroff KR, Ingham JM. Care for the caregivers: a review of self-report instruments developed to measure the burden, needs, and quality of life of informal caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003. October;26(4):922–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones C, Edwards RT, Hounsome B. Health economics research into supporting carers of people with dementia: a systematic review of outcome measures. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012. November 26;10:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coughlin SS. Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(1):87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassan E Recall bias can be a threat to retrospective and prospective research designs. The Internet J Epidemiol. 2006;3(2):4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redelmeier DA, Dickinson VM. Determining whether a patient is feeling better: pitfalls from the science of human perception. J Gen Intern Med. 2011. August;26(8):900–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlesimo GA, Fadda L, Sabbadini M, Caltagirone C. Recency effect in Alzheimer’s disease: a reappraisal. Q J Exp Psychol A. 1996. May;49(2):315–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wild KV, Mattek N, Austin D, Kaye JA. “Are You Sure?”: Lapses in Self-Reported Activities Among Healthy Older Adults Reporting Online. J Appl Gerontol. 2016. June;35(6):627–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotrell V, Wild K, Bader T. Medication management and adherence among cognitively impaired older adults. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2006;47(3-4):31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallihan DB, Stump TE, Callahan CM. Accuracy of self-reported health services use and patterns of care among urban older adults. Med Care. 1999. July;37(7):662–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyons BE, Austin D, Seelye A, Petersen J, Yeargers J, Riley T, et al. Corrigendum: pervasive computing technologies to continuously assess Alzheimer’s disease progression and intervention efficacy. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015. December;7:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaye JA, Maxwell SA, Mattek N, Hayes TL, Dodge H, Pavel M, et al. Intelligent Systems For Assessing Aging Changes: home-based, unobtrusive, and continuous assessment of aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011. July;66 Suppl 1:i180–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teri L, McCurry SM, Logsdon R, Gibbons LE. Training community consultants to help family members improve dementia care: a randomized controlled trial. Gerontologist. 2005. December;45(6):802–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cisco: Cisco TelePresence Server Data Sheet, 2014. Available from: https://www.cisco.com

- 21.Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001. October;41(5):652–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teri L, Truax P, Logsdon R, Uomoto J, Zarit S, Vitaliano PP. Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: the revised memory and behavior problems checklist. Psychol Aging. 1992. December;7(4):622–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andresen EM, Byers K, Friary J, Kosloski K, Montgomery R. Performance of the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale for caregiving research. SAGE Open Med. 2013. December;1:2050312113514576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munro BH. Statisical Methods for Health Care Research. 5th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benner P The tradition and skill of interpretive phenomenology in studying health, illness, and caring practices. In: Benner P, editor. Interpretive phenomenology: embodiment, caring, and ethics in health and illness. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. p. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975. November;12(3):189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993. November;43(11):2412–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994. December;44(12):2308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982. May;37(3):323–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Austin D, Cross RM, Jacobs P, Mattek NC, Petersen J, Wild K, et al. Predicting transitions to higher levels of care among elderly: a behavioral approach. Gerontological Society of America Annual Conference, Washington, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Välimäki T, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K, Pietilä AM. Diaries as research data in a study on family caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease: methodological issues. J Adv Nurs. 2007. July;59(1):68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ, Diguiseppi C, Wentz R, Kwan I, et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. July;(3):MR000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindauer A, Croff R, Mincks K, Mattek N, Shofner SJ, Bouranis N, et al. “It took the stress out of getting help”: the STAR-C-Telemedicine mixed methods pilot. Care Wkly. 2018;2:7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seelye A, Mattek N, Howieson D, Riley T, Wild K, Kaye J. The impact of sleep on neuropsychological performance in cognitively intact older adults using a novel in-home sensor-based sleep assessment approach. Clin Neuropsychol. 2015;29(1):53–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaye J, Mattek N, Dodge H, Buracchio T, Austin D, Hagler S, et al. One walk a year to 1000 within a year: continuous in-home unobtrusive gait assessment of older adults. Gait Posture. 2012. February;35(2):197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wild K, Boise L, Lundell J, Foucek A. Unobtrusive In-Home Monitoring of Cognitive and Physical Health: Reactions and Perceptions of Older Adults. J Appl Gerontol. 2008;27(2):181–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]