Abstract

A series of semisynthetic triterpenoids with A-ring azepano- and A-seco-fragments as well as hydrazido/hydrazono-substituents at C3 and C28 has been synthesized and evaluated for antimicrobial activity against key ESKAPE pathogens and DNA viruses (HSV-1, HCMV, HPV-11). It was found that azepanouvaol 8, 3-amino-3,4-seco-4(23)-en derivatives of uvaol 21 and glycyrrhetol-dien 22 as well as azepano-glycyrrhetol-tosylate 32 showed strong antimicrobial activities against MRSA with MIC ≤ 0.15 μM that exceeds the effect of antibiotic vancomycin. Azepanobetulinic acid cyclohexyl amide 4 exhibited significant bacteriostatic effect against MRSA (MIC ≤ 0.15 μM) with low cytotoxicity to HEK-293 even at a maximum tested concentration of >20 μM (selectivity index SI 133) and may be considered a noncytotoxic anti-MRSA agent. Azepanobetulin 1, azepanouvaol 8, and azepano-glycyrrhetol 15 showed high potency towards HCMV (EC50 0.15; 0.11; 0.11 µM) with selectivity indexes SI50 115; 136; 172, respectively. The docking studies suggest the possible interactions of the leading compounds with the molecular targets.

Subject terms: Virtual drug screening, Chemical modification, Medicinal chemistry

Introduction

Microbial infections, such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses, are a cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. Increased resistance to bacterial and viral infections requires the search for new antibiotic and antiviral drugs [2]. Natural products have historically been a prolific and unsurpassed source for new lead antibacterial compounds and therefore novel scaffolds are constantly of interest. Many secondary metabolites from plants consisting of terpenes and polyphenols can combat the problem of resistant bacteria and viruses as well as drug residue hazards [3]. A wide variety of these compounds have shown to exhibit activity against various bacterial and viral pathogens, yeasts, or molds [4, 5] and also served as prototypes, which have been modified through chemical synthesis to afford therapeutic agents with improved potency, stability, or superior drug-like properties [6, 7].

Pentacyclic triterpenoids are widespread in the plant kingdom and display important biological properties, such as anticancer, antiviral, antibacterial, and antimalarial activities, among others [8–13]. Thus, α-amyrin, betulinic acid, and betulin aldehyde exhibit the antimicrobial activity against clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus with MICs ranging from 64 to 512 μg ml−1, and in combination with vancomycin and methicillin the reduced MIC with a range from 0.05 to 50% was observed [14]. Oleanolic acid has been shown to exhibit appreciable anti-staphylococcal activity against S. aureus and MRSA, with MICs in the range of 8 and 16 μg ml−1 [15], whereas ursolic acid showed a good antimicrobial activity against gram (+) pathogens including a MRSA strain, with a MIC value of 64 µg ml−1 and a synergistic effect with ampicillin and tetracycline against this strain [16]. As early as 1994, betulinic acid was shown to inhibit the infectivity of HIV-1 in vitro with EC50 value of 1.4 μM [17] and its systematic structural modifications resulted in the identification of bevirimat, BMS-955176 and GSK-2838232 entered clinical trials [18]. Up to date, various other triterpenoid lead compounds targeting HCV/EBOV, SARS-CoV, and influenza viruses have been explored [19–21].

In order to further study the antimicrobial and antiviral potency of triterpenic derivatives, a series of semisynthetic derivatives with A-ring azepano- as well as hydrazido/hydrazono-substituents at C3 and C28 were evaluated against a key ESKAPE pathogens (including MRSA strain) and DNA viruses (human herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), cytomegalovirus, and papillomavirus 11). For this purpose, we used the possibilities of the Community for Open Antimicrobial Drug Discovery program (http://www.co-add.org) for antibacterial and antifungal activities screening and Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (http://www.niaid-aacf.org/) program for antiviral assays. Cytotoxicity of the representative compounds against the noncancerous human embryonic kidney cells was studied as well as docking studies of the leading compounds possible interactions with the molecular targets was performed.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

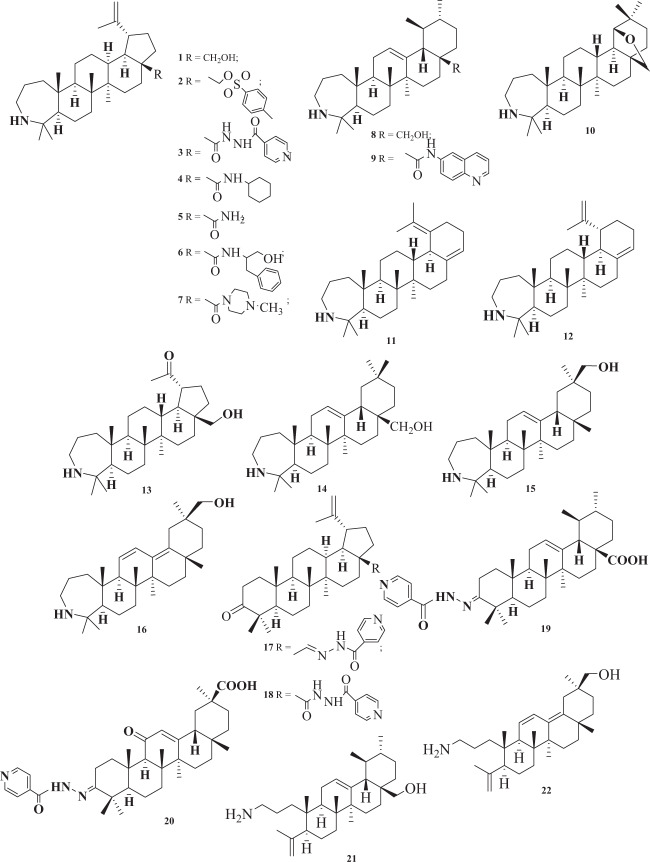

Recently we have showed that triterpenoids with A-ring azepano- and hydrazido-, hydrazono-substituents are an important group of derivatives with antibacterial activities [22–25]. To compare the influence of substituents in different positions of the triterpene core on antibacterial, fungicidal, and antiviral activities, a series of previously synthesized compounds 1–22 (Fig. 1) and new derivatives 24, 26, 29–34, 36, 37 (Scheme 1) were taken into biological screening.

Fig. 1.

Azepano-, hydrazido/hydrazono-, and seco-triterpenic derivatives: azepanobetulin 1, tosylate 2, acetohydrazide 3, amides 4–7, 9, azepanouvaol 8, azepanoallobetulin 10, abeo-lupanes 11 and 12, azepanomessagenin 13, azepanoerythrodiol 14, azepano-glycyrrhetinic 15 and 16, hydrazones 17, 19, 20, hydrazide 18, 3-amino-3,4-seco-4(23)-en triterpenic derivatives of uvaol 21, and glycyrrhetol-dien 22

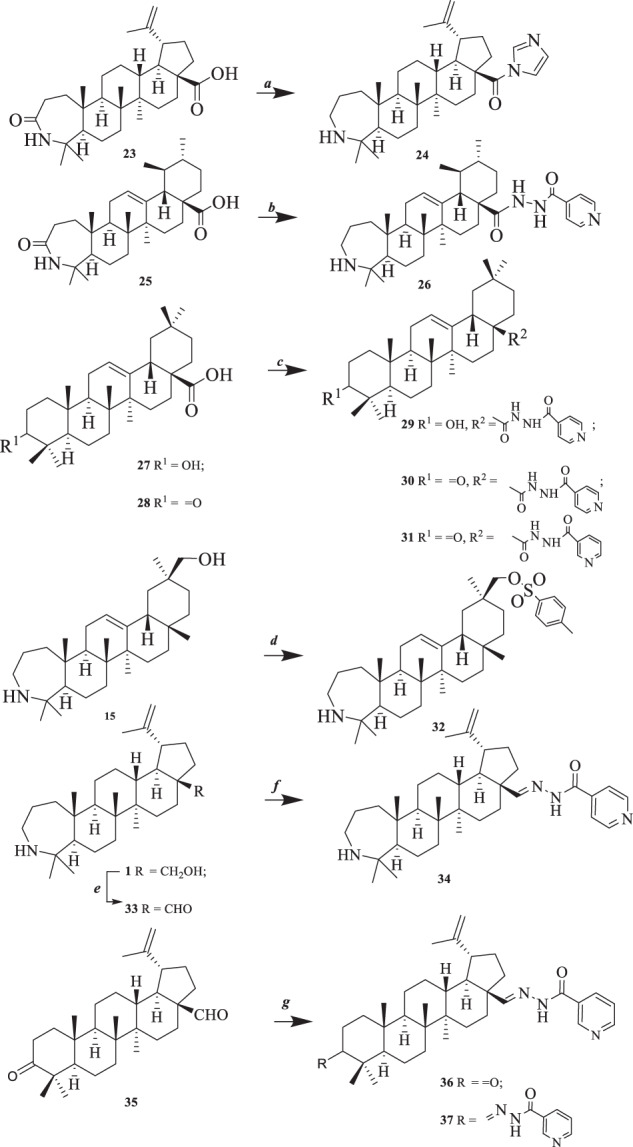

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 24, 26, 29–34, 36, 37. Reagents and conditions: a (1) (COCl)2, CH2Cl2, 22 °С, 3 h; (2) imidazole, DMAP, CH2Cl2, reflux, 3 h; (3) LiAlH4, THF, reflux, 1 h; b (1) (COCl)2, CH2Cl2, 22 °С, 3 h; (2) 4-pyridinoylhidrazide, CH2Cl2, reflux, 3 h; (3) LiAlH4, THF, reflux, 1 h; c (1) (COCl)2, CH2Cl2, 22 °С, 3 h; (2) 4-pyridinoylhidrazide for compounds 29, 30 and 3-pyridinoylhidrazide for compound 31, CH2Cl2, reflux, 3 h; d p-TsCl, pyridine, DMAP, 48 h, 22 °C; e PCC, CH2Cl2, rt, 30 min; f 4-pyridinoylhidrazide, MeOH, 22 °C, 8 h. g 3-pyridinoylhidrazide, MeOH, 22 °C, 6 h

The synthesis of new derivatives is shown at Scheme 1. N-Acylation of lupane, ursane and oleanane-type triterpenic acids 23, 25 and 27, 28 by imidazole, 3- or 4-pyridinoylhydrazides by chloride method led to C28-amides 24, 26, 29–31 with yields of 72–78% after purification by column chromatography. The introduction of the toluenesulfonyl group to azepano-glycyrrhetol was carried out by the reaction of 15 with p-TsOH to give compound 32 in 88% yield. Azepanobetulin 1 was oxidized to azepanobetulinic aldehyde 33 by PCC in CH2Cl2 and following reaction with 4-pyridinoylhydrazide in MeOH afforded hydrazido-hydrazone 34. Under the same conditions betulonic aldehyde 35 was reacted with 3-pyridinoylhydrazide to form a mixture of C28-mono- 36 (65%) and C3,C28-bis-substituted 37 (7%) derivatives after isolation by column chromatography.

The structures and the purity of the synthesized compounds 24, 26, 29–34, 36, and 37 were confirmed by NMR spectroscopy. In the 13C NMR spectra of compounds 24, 26, 29–31 the carbon atom signals of the –CONH– and –NHCO– groups were detected at δ 174.0–174.73 and δ 161.62–161.90 ppm, respectively, in the 1H NMR spectra NH proton signals resonated at δ 9.21–10.71 ppm. The 1H NMR spectra of amide 24 contained the signals of the imidazole ring protons at δ 7.02–7.52 ppm as well as in the 1H NMR spectra of hydrazides 26, 29–31 the signals of the aromatic ring protons were observed at δ 7.38–8.64 ppm. In the 13C NMR spectra of tosylate 32 the signals of the aromatic carbon atoms were observed at δ 123.08–144.64 ppm, and the signals of the aromatic protons in the 1H NMR spectra were appeared at δ 7.35 and 7.75 ppm as multiplets. The characteristic signal of aldehyde group proton at δ 9.80 ppm and signal of the carbon atom at δ 202.0 ppm were observed in the NMR spectra of compound 33. The 13C NMR spectra of compounds 34, 36, 37 contain –C = N-NH– group carbon signal at δ 161.96–166.0 ppm, the NH proton in the 1H NMR spectra appeared as a broadened signal at δ 10.05–10.99 ppm.

Thus, a series of new A-azepanotriterpenoids as well as C28-amides, C3, C28-dihydrazides, and isonicotinoylhydrazones has been synthesized for biological screening.

Biological activity

Evaluation of antimicrobial activity

Despite the discovery of antibiotics that have saved millions of lives from microbial infections, the latter continue to pose a serious threat to public health due to the emergence of resistant strains. MRSA Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most prevalent triggers of community-associated multi drug resistance bacterial infection and resistance to methicillin is now widely described in the community setting, thus the development of new drugs or alternative therapies is urgently necessary [26, 27].

Plant-derived triterpenoids represent a promising class of molecules with a multitude of activities, including antimicrobial, that make them of reference for drug-discovery as proven by the numerous reports and even clinical trials [5, 28, 29]. Recently, we have shown that 3-amino-3,4-seco-28-amino-lup-4(23),20(29)-dien exhibited significant bacteriostatic effect against MRSA (MIC ≤ 0.25 μg ml−1) that exceeds the effect of vancomycin [23]. Oleanonic acid amide with diethylentriamine was efficient against E. coli and P. aeruginosa with MICs of 25 and 50 µM [30]. Azepanobetulin and its amide derivative showed in vitro antibacterial activity on the H37Rv MTB strain in aerobic and anaerobic conditions and antibacterial potency against nontuberculous mycobacterial strains (M. avium, M. abscessus) [31], and also triterpene conjugates with hydrazine hydrate and isoniazide demonstrated from high minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC ≤ 10 μg ml−1) to excellent (MICs from 0.19 to 1.25 μg ml−1) activity against MTB H37RV and some SDR-strains [24].

Due to our interest in the discovery and development of anti-infective compounds, semisynthetic triterpenoids 1–4, 8–22, 26, 29–32, 34, 36, 37 were screened for antibacterial activity against a panel of gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial isolates, and for antifungal activity against two fungi at concentration 20 μM. The percentage of growth inhibition was calculated for each well, using the negative control (media only) and positive control (bacteria without inhibitors) on the same plate as references.

The initial screening results of in vitro antimicrobial activity are presented in Table 1. Samples with inhibition values equal to or above 80% were classified as active. Compounds 17–20, 26, 29–31, 36, 37 did not exhibit antibacterial activity against the gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus MRSA), or gram-negative (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) bacteria tested and were also inactive against fungi (Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans) at 20 μM.

Table 1.

Percentage antibacterial and antifungal growth inhibition of compounds 1–4, 8–22, 26, 29–32, 34, 36, and 37 at concentration 20 μMa

| Compound | Gram-positive bacteria | Gram-negative bacteria | Fungi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | E. coli | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | A. baumannii | C. albicans | C. neoformans | |

| 1 | 99.76 | −0.25 | 7.50 | 23.35 | 20.01 | 8.38 | 98.72 |

| 2 | 92.85 | 9.61 | 3.96 | −0.92 | 17.53 | 101.70 | 101.50 |

| 3 | 47.83 | −4.72 | 4.78 | −3.74 | 28.31 | 11.74 | 95.40 |

| 4 | 94.50 | 16.13 | 13.10 | −4.37 | 23.25 | 101.00 | 95.14 |

| 8 | 97.80 | 15.15 | −1.29 | 23.40 | 32.17 | 18.07 | 98.21 |

| 9 | 84.80 | −6.12 | 19.57 | −8.27 | 45.49 | 100.40 | 96.16 |

| 10 | 94.72 | −1.37 | −15.47 | 5.25 | 12.84 | 100.10 | 96.93 |

| 11 | 87.80 | 0.85 | 1.07 | 5.04 | 16.18 | 100.70 | 91.82 |

| 12 | 97.63 | 1.92 | −8.12 | −0.30 | 16.58 | 101.60 | 101.80 |

| 13 | 98.34 | 2.59 | 6.61 | 18.49 | 7.65 | 12.53 | −6.14 |

| 14 | 98.25 | 21.81 | 18.85 | 13.01 | 33.54 | 101.50 | 112.50 |

| 15 | 98.96 | 7.17 | 14.41 | 25.39 | 34.72 | 100.40 | 100.30 |

| 16 | 99.07 | 1.64 | 1.86 | 14.57 | 41.07 | 99.54 | 100.30 |

| 17 | 9.62 | −3.99 | 5.25 | −6.21 | 19.13 | 17.50 | −12.79 |

| 18 | 18.34 | −1.26 | 2.91 | 3.81 | 39.78 | 62.06 | 1.53 |

| 19 | 9.06 | −0.71 | 12.60 | 8.48 | 34.89 | 4.77 | −3.32 |

| 20 | 0.19 | −3.33 | −0.30 | 3.96 | 37.10 | 7.47 | −2.81 |

| 21 | 91.97 | 19.03 | 6.36 | 10.65 | 29.64 | 21.82 | 95.14 |

| 22 | 90.28 | 23.74 | 24.29 | 9.90 | 36.00 | 99.58 | 101.90 |

| 26 | 6.66 | 1.45 | 12.58 | 6.19 | 15.42 | 7.32 | −1.15 |

| 29 | −4.12 | −4.64 | −4.92 | 3.81 | 0.87 | 7.53 | −11.51 |

| 30 | 14.72 | 0.30 | 3.19 | 1.55 | 10.69 | 10.53 | −8.72 |

| 31 | −5.16 | −1.34 | −9.72 | 7.12 | −6.61 | 15.45 | 17.65 |

| 32 | 97.00 | 2.89 | 9.14 | 0.87 | 13.08 | 100.30 | 102.40 |

| 34 | 97.34 | 0.01 | −12.00 | 12.77 | 21.96 | 100.6 | 105.1 |

| 36 | 14.78 | 3.08 | 10.74 | 16.58 | 13.81 | 8.44 | 1.52 |

| 37 | −10.09 | −3.06 | −6.88 | 8.30 | 7.18 | 9.58 | 17.65 |

aHighest percentile of antibacterial/antifungal growth inhibition is highlighted in bold

On the other hand, compounds 1, 2, 4, 8–16, 21, 22, 32, 34 showed the highest growth inhibition against S. aureus bacteria culture with ranged from 84.80% to 99.76% as well as compounds 2, 4, 9–12, 14–16, 22, 32, 34 had excellent fungicidal activity against culture of fungi’s C. albicans and C. neoformans var. grubii. Compounds 1, 3, 8, and 21 were also active against fungi C. neoformans (Table 1).

Triterpenic alcohols 1, 8 and 3,4-seco-uvaol 21 were active against bacteria S. aureus and fungi C. neoformans, whereas, azepanoallobetulin 10, abeo-lupanes 11, 12, azepanoerythrodiol 14, azepano-glycyrrhetinic 15, 16, and 3,4-seco-derivatives of glycyrrhetol-dien 22 inhibited the S. aureus and both studied fungi’s. Аzepanomessagenin 13 was active only against gram-positive MRSA. The introduction of the toluenesulfonyl fragment (compound 2) leads to the appearance of activity against C. albicans as compared with the initial compound 1, tosylate 32 also has activity against two fungi’s and MRSA. A similar activity is observed for amides 4 and 9. The introduction of a pyridinoylhydrazide residues into the C3 and/or C28 positions of triterpene derivatives leads either to a complete loss of antimicrobial activity (hydrazones 17, 19, 20, 36, 37 and hydrazides 18, 26, 29–31), or to a partial loss of activity against MRSA (acetohydrazide 3), and only in the case of hydrazone 34, an increase of activity was observed in comparison with the initial alcohol 1.

Among the samples tested, eighteen showed antimicrobial activity and have been selected for hit-confirmation. For these compounds, a minimum inhibitory concentration and cytotoxicity against a human embryonic kidney cell line (μM) were determined for the above cultures of bacteria and fungi. Colistin and vancomycin were used as positive antibacterial controls for gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, respectively. Fluconazole was used as a positive antifungal control for C. albicans and C. neoformans. Tamoxifen was used as a positive cytotoxicity standard (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antibacterial activity (MIC, μΜ (SI)) for the compounds 1–4, 8–16, 21, 22, 20, and 34

| Compound | Gram-positive bacteria | Gram-negative bacteria | Fungi | Mammalian cells | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | E. coli | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | A. baumannii | C. albicans | C. neoformans | HEK-293 (CC50)a | ||

| 1 | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 | |

| 2 | 1.25 (0.1) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | ≤0.15 (<0.83) | >20 (<0.01) | ≤0.125 | |

| 3 | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 | |

| 4 | ≤0.15 (133) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 | |

| 8 | ≤0.15 (1.51) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | 0.227 | |

| 9 | 5 (1.49) | >20 (<0.37) | >20 (<0.37) | >20 (<0.37) | >20 (<0.37) | >20 (<0.37) | >20 (<0.37) | 7.493 | |

| 10 | 5 (0.65) | >20 (<0.16) | >20 (<0.16) | >20 (<0.16) | >20 (<0.16) | 10 (<0.32) | >20 (<0.16) | 3.228 | |

| 11 | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 | |

| 12 | 2.50 (0.05) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | ≤0.15 (<0.83) | >20 (<0.01) | ≤0.125 | |

| 13 | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 | |

| 14 | 1.25 (1.07) | >20 (<0.07) | >20 (<0.07) | >20 (<0.07) | >20 (<0.07) | >20 (<0.07) | >20 (<0.07) | 1.335 | |

| 15 | 2.50 (4.36) | >20 (<0.5) | >20 (<0.5) | >20 (<0.5) | >20 (<0.5) | >20 (<0.5) | 10 (1.1) | 10.90 | |

| 16 | 10 (<2) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 | |

| 21 | ≤0.15 (0.83) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | 10 (<0.01) | ≤0.125 | |

| 22 | ≤0.15 (0.83) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | 1.25 (<0.1) | 20 (<0.01) | ≤0.125 | |

| 32 | ≤0.15 (1.16) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | >20 (<0.01) | 0.174 | |

| 34 | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | >20(<1) | >20 (<1) | >20 (<1) | |

| Colistin sulfate | – | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | – | − | – | |

| Vancomycin-HCl | 0.625 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| fluconazole | – | – | – | – | – | 0.08 | 5 | – | |

| tamoxifen | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5.625 | |

aCC50 (concentration at 50% cytotoxicity)

SI selectivity index (CC50/MIC)

Notably, compounds 1, 3, 11, 13, and 34 do not show antibacterial activity after the repeated screening. Compounds 2, 9, 10, 12, and 14–16 showed weak activity against MRSA S. aureus (MIC ranges from 1.25 to 10 μM), while the compounds 4, 8, 21, 22, and 32 exhibited significant bacteriostatic effect against MRSA (MIC ≤ 0.15 μM) that exceeds the effect of the clinically used antibiotic vancomycin (MIC = 0.625 μM). Compounds 2, 10, 12, and 22 were also active against fungi C. albicans (MIC ≤ 0.15 μM for compounds 2 and 12; MIC = 1.25 μM for compound 22, and MIC = 10 μM for compound 10) whereas compounds 15, 21, and 22 inhibited the growth of fungi C. neoformans (MIC ranges from 10 to 20 μM) (Table 2).

To study the drug-like properties of the active compounds, all eighteen compounds were evaluated for cytotoxic properties for 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) values against healthy human (HEK-293) cells and selectivity (SI = CC50/MIC) (Table 2). The values of cytotoxicity of triterpene derivatives 2, 8–10, 12, 14, 15, 21, 22, and 32 were comparable with the values of the minimum inhibitory concentrations for bacteria S. aureus and fungi C. albicans and C. neoformans, suggesting that these compounds do not have clear selectivity between microbial and human cells. Azepanobetulinic acid amide 4 and azepano-glycyrrhetol 16 did not show any noticeable cytotoxicity against HEK-293 cell lines and the selectivity index values for these compounds were 133 and 2, respectively. This finding is very significant to design azepanotriterpenoids as noncytotoxic antibacterial agents.

Evaluation of antiviral activity

Viral infections cause many serious human diseases with high mortality rates. Given the high mutation rate of viruses and their serious threat to public health, there is a high urgency to develop new antiviral drugs to combat these pathogens. Triterpenoids have also been crucial for antiviral drug discovery [32] and mainly involve effects on DNA viruses [33–35]. For example, Bevirimat [3-O-(3′,3′-dimethylsuccinyl)-betulinic acid] has been shown to inhibit HIV-1 maturation by a previously undescribed mechanism [33]. Betulin alone and in combination with acyclovir has been reported to inhibit Herpes simplex virus types I and II [36]. Betulinic and betulonic acids are also active against HSV, as well as against influenza A and ECHO-6 picornavirus [37, 38]. The synergistic effect of rimantadine and betulin-derived compounds combinations against reproduction influenza virus type A (H1N1, H7N1, and H3N2) and B in vivo is established [39]. Recent data provide evidence for the sensitivity of RNA viruses, for example, the significant synergistic effects of betulin derivatives, when combined with 3′-amino-3′-deoxy-adenosine against Semliki Forest virus was shown [40].

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is an opportunistic viral pathogen of the Herpesviridae family which infects newborns and immunosuppressed individuals with high virulence, leading to severe morbidity and mortality. It was shown that betulin/betulinic acid and artesunic acid hybrids [41] and triazine derivatives of allobetulin and betulinic acid [42] were active against HCMV with EC50 in the micromolar range.

Papillomaviruses are small, non-enveloped DNA viruses that infect and replicate in the cutaneous or mucosal epithelia of human and other mammals [43]. There are over 80 types of human papillomavirus (HPV), which cause conditions ranging from plantar (HPV-1) and genital warts (HPV-6 and -11) to cervical cancer (HPV-16, - 18, and -31). HPV-6 and -11 are also responsible for laryngeal papillomatosis, a rare but very serious infection of the respiratory tract. Antiviral agents capable of specifically inhibiting PV replication could play an important role in the treatment of these diseases, but unfortunately, no such efficient antiviral agent exists at present. A series of triterpenoids were found to inhibit HPV-11 and HPV-16 in the micromolar range [44–46].

We submitted compounds 1, 2, 5–8, 10, 12, 14–16, and 24 to the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of the NIAID for antiviral testing. The NIAID selected a panel of viruses [HCMV, HSV-1, and HPV 11 (HPV-11)] for in vitro screening of these compounds. The detailed information regarding antiviral screening and methods can be found at http://www.niaid-aacf.org/ and were described in the literature [47, 48].

The azepanobetulinic amide 6 and azepanoerythrodiol 14 have shown good viral inhibition towards HSV-1 (EC50, EC90 > 1.20 µM) compared to standard drug Acyclovir (EC50 = 0.83 µM; EC90 > 150 µM). The azepanotriterpenoids 1, 8, 12, 15 and azepanobetulinic amides 5, 24 are active against HSV-1 with EC50 > 6 µM; EC90 > 6 µM (Table 3).

Table 3.

In vitro antiviral activity of compounds 1, 2, 5–8, 10, 12, 14–16, and 24

| Compound (ARB no.) | EC50 | EC90 | CC50 | SI50 | SI90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herpes simplex virus 1a | |||||

| 1 (17-000257) | >6 | >6 | 25.67 | <4 | <4 |

| 6 (17-000261) | >1.20 | >1.20 | 3.22 | <3 | <3 |

| 8 (17-000259) | >6 | >6 | 7.87 | <1 | <1 |

| 14 (17-000258) | >1.20 | >1.20 | 2.78 | <2 | <2 |

| 15 (17-000260) | >6 | >6 | 10.63 | <2 | <2 |

| Acyclovir | 0.83 | >150 | >150 | >181 | 1 |

| 5 (17-000262) | >6 | >6 | 12.76 | <2 | <2 |

| 12 (17-000263) | >6 | >6 | 14.91 | <2 | <2 |

| 24 (17-000264) | >6 | >6 | 6.14 | <1 | <1 |

| Acyclovir | 0.87 | >150 | >150 | >172 | 1 |

| Human cytomegalovirusb,c | |||||

| 1 (17-000257) | 0.15 | >6 | 17.20 | 115 | <3 |

| 6 (17-000261) | >1.20 | >1.20 | 3.24 | <3 | <3 |

| 8 (17-000259) | 0.11 | >6 | 14.79 | 136 | <2 |

| 14 (17-000258) | >1.20 | >1.20 | 3.49 | <3 | <3 |

| 15 (17-000260) | 0.11 | >6 | 18.58 | 172 | <3 |

| Ganciclovir | 0.24 | 1.08 | >150 | >625 | >139 |

| 5 (17-000262) | >1.20 | >1.20 | 4.08 | <3 | <3 |

| 12 (17-000263) | >6 | >6 | 15.32 | <3 | <3 |

| 24 (17-000264) | >0.24 | >0.24 | 1.18 | <5 | <5 |

| Ganciclovir | 0.80 | >150 | >150 | >187 | 1 |

| 2 (18-000052) | >1.20 | >1.20 | 3.81 | <3 | <3 |

| 7 (18-000053) | >30 | >30 | 86.48 | <3 | <3 |

| 10 (18-000051) | >30 | >30 | 89.45 | <3 | <3 |

| 16 (18-000049) | >30 | >30 | 80.86 | <3 | <3 |

| Ganciclovir | 1.11 | >150 | >150 | >135 | 1 |

| 1 (17-000257) | >6 | >6 | 18.71 | <3 | <3 |

| 8 (17-000259) | >6 | >6 | 16.14 | <3 | <3 |

| 15 (17-000260) | >6 | >6 | 17.56 | <3 | <3 |

| Ganciclovir | >150 | >150 | >150 | 1 | 1 |

| Cidofovir | 0.92 | >30 | 110.24 | 120 | <4 |

| Human papillomavirus 11d | |||||

| 1 (17-000257) | >6 | >6 | 11.89 | <2 | <2 |

| 5 17-000262) | >1.20 | >1.20 | 5.16 | <4 | <4 |

| 6 (17-000261) | >0.24 | >0.24 | 0.78 | <3 | <3 |

| 8 (17-000259) | >1.20 | >1.20 | 3.32 | <3 | <3 |

| 12 (17-000263) | >1.20 | >1.20 | 4.79 | <4 | <4 |

| 14 (17-000258) | >0.24 | >0.24 | 0.78 | <3 | <3 |

| 15 (17-000260) | >1.20 | >1.20 | 1.34 | <1 | <1 |

| 24 (17-000264) | 1.07 | >1.20 | 2.83 | 3 | >2 |

| 9-[2-(Phosphonomethoxy)ethyl]guanine | 0.68 | 100.62 | >150 | >221 | >1 |

EC50—compound concentration that reduced viral replication by 50%; EC90—compound concentration that reduced viral replication by 90%; CC50—compound concentration that reduced cell viability by 50%; SI50—selectivity index (CC50/EC50)

aVirus strain: E-377; cell line: HFF; vehicle: DMSO; drug conc. range: 0.048–150 μM; control conc. range: 0.048–150 μM; experiment number: 17-hsv1-033 for 1, 6, 8, 14, 15; 17-hsv1-034 for 5, 12, 24; control assay order: primary; control assay name: CellTiter-Glo (cytopathic effect/toxicity)

bVirus strain: AD169; cell line: HFF; vehicle: DMSO; drug conc. range: 0.048–150 μM; control conc. range: 0.048–150 μM; experiment number: 17-hcmv-028 for 1, 6, 8, 14, 15; 17-hcmv-029 for 5, 12, 24; 18-hcmv-009 for 2, 7, 10, 16; control assay order: primary; control assay name: CellTiter-Glo (cytopathic effect/toxicity)

cVirus strain: GDGr K17 (resistant isolate); cell line: HFF; vehicle: DMSO; drug conc. range: 0.01–30 μM; control conc. range: 0.048–150 μM; experiment number: 17-hcmvR-041 for 1, 8, 15; control assay order: primary; control assay name: CellTiter-Glo (cytopathic effect/toxicity)

dVirus strain: HE611260.1; cell line: C-33 A; vehicle: DMSO; drug conc. range: 0.048–150 μM; control conc. range: 0.048–150 μM; experiment number: 17-hpv11-013; control assay name: Nano-Glo Luciferase (Nanoluc)/CellTiter-Glo (toxicity)

Just like HSV-1, compounds 2, 5, and 24, (EC50 > 1.20; >1.20 and >0.24 µM) turned out to be active towards HCMV for normal strain AD169 compared to Ganciclovir (EC50 = 1.11 µM (2); EC50 = 0.80 µM (5, 24)), and triterpenoids 6 and 14 showed weak activity with EC50 > 1.20 µM (ganciclovir EC50 = 0.24 µM). Amide 7, azepanoallobetulin 10, abeo-lupane 12, and azepano-glycyrrhetol 16 were inactive against HCMV. The azepanobetulin 1, azepanouvaol 8, and azepano-glycyrrhetol 15 showed very high potency towards HCMV (EC50 0.15; 0.11; 0.11 µM, respectively), and relatively low toxicity (CC50 17.20; 14.79; 18.58 µM) with selectivity index (SI50 115; 136; 172) compared to standard drug Ganciclovir (EC50 0.24 µM; CC50 > 150.00 µM; SI50 > 625 µM). The EC50 and EC90 values for compounds 1, 8, 15 against the resistant isolate GDGr K17 were higher than the values for the reference drug ganciclovir (EC50 > 150 μM; EC90 > 150 μM), but at the same time lower EC50 value for cidofovir (EC50 = 0.92 µM).

The selectivity index (SI50) for compounds 1, 5, 6, 8, 12, 14, 15, and 24 against HPV-11 ranged from 3 to <4. The amide 6 and azepanoerythrodiol 14 showed the best potency (EC50; EC90 > 0.24 µM) compared to standard drug 9-[2-(phosphonomethoxy)ethyl]guanine (EC50 0.68 µM; EC90 100.62 µM) (Table 3).

Molecular modeling

Antibacterial activity

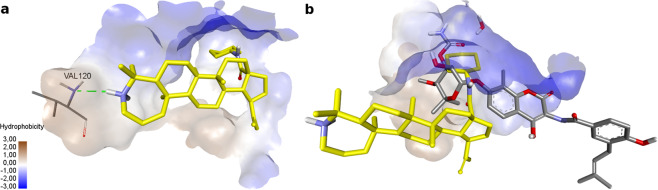

In order to search for a possible mechanism of the antibacterial action of compound 4 against S. aureus, we performed molecular modeling of its possible interaction with a number of bacterial targets. A low estimated binding energy was obtained by docking compound 4 in S. aureus topoisomerase IV. Bacterial topoisomerase is involved in the processes of replication, damage repair, and topology changes of DNA molecule and, therefore, is an attractive target for the design of new inhibitors that will have antibacterial effects [49, 50]. We used the S. aureus topoisomerase IV XRD model with PDB ID 4URN [51] (resolution 2.9 Å) for calculations.

The topoisomerase XRD model under consideration is co-crystallized with a naturally occurring antibiotic novobiocin. The authors of the model make a conclusion about the complex configuration of the binding site, which affects the resistance of topoisomerase to the action of antibiotics [51]. New antibiotics can occupy additional areas of the binding site and take on other conformations, overcoming resistance.

In this regard, according to docking the location of compound 4 in the binding site is interesting: it is able to penetrate into the deep pocket of the binding site with its aminocyclohexane group simulating the conformation of novobiocin. The azepane-triterpene backbone of this derivative occupies a mirror position relative to the novobiocin molecule (Fig. 2b), stabilizing its conformation due to the hydrogen bond of the protonated nitrogen atom of the azepane ring with the amino acid residue Val120 (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a Docking of compound 4 (−3.413 kcal/mol) in S. aureus topoisomerase IV. Hydrogen bonds are shown by dashed green lines, hydrophobic interactions are omitted. b Superposition of the structures of compound 4 (yellow) and novobiocin (gray) at the topoisomerase binding site

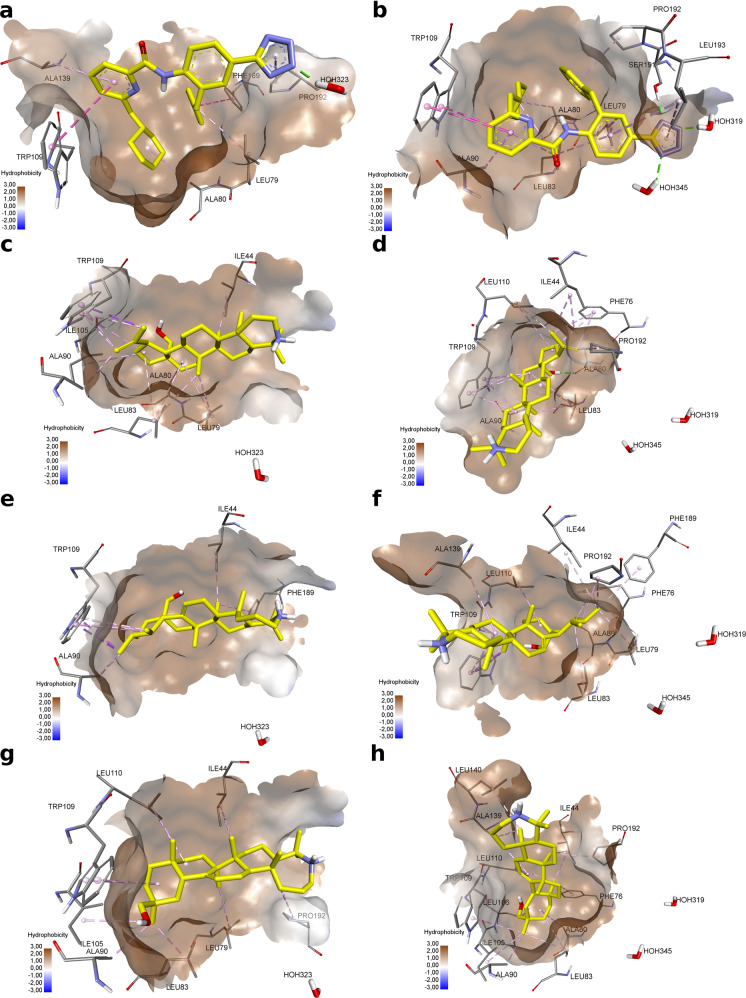

Antiviral activity

Considering the pronounced antiviral activity of compounds 1, 8, and 15 against cytomegalovirus, an attempt was made to simulate a possible mechanism of the antiviral effect of these compounds. All human herpes viruses possess a structurally and functionally conserved serine protease [52]. This protease is critical for the formation of the viral nucleocapsid and is activated allosterically as a result of the dimerization process. Given one of the key roles of serine protease in the replication cycle of herpes viruses, it appears that inhibitors of this enzyme may be effective antiviral agents [53]. The development of covalent inhibitors capable of binding to the substrate-binding site has become a complex process due to its surface location, the absence of a deep cavity, and the high variability of its spatial organization [54, 55]. The allosteric nature of the activation of this enzyme is associated with two structurally different active sites of each monomer. Dimer formation leads to activation of the catalytic binding site. In this regard, blocking allosteric dimerization sites can lead to inhibition of viral protease activity [56]. To simulate a possible inhibition of allosteric dimerization of herpes virus protease by new azepanbetulin derivatives the XRD model of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) protease in complex with dimer disruptor with PDB ID 4P3H [56] (resolution 1, 45 Å) was chosen.

The active sites of dimerization of asymmetric monomers of the viral protease are deep hydrophobic cavities, in which the binding of possible dimer disruptors can be carried out mainly through hydrophobic interactions. Both sites are characterized by an open rotameric conformation of the Trp109 side chain, the pi system of which enters into stacking interactions with the pyrimidine ring of the dimer disruptor. In both sites, the disruptor molecule interacts with the amino acid residue Pro192 and water molecules. A specific feature of the binding of the disruptor in the active site of monomer B is the formation of a hydrogen bond with the Ser191 amino acid residue.

Modeling the interaction of new azepanbetulin derivatives with active sites of dimerization shows that the hydrophobicity of their triterpene scaffolds contributes to the formation of a large number of hydrophobic interactions in the depth of the binding cavity. All derivatives can interact with Trp109. Compounds 1 and 8 interact with Pro192 only in the active site of monomer B, while compound 15 interacts with it in both active sites of monomers. The polar groups of the new derivatives are apparently unable to form hydrogen bonds with water molecules and the Ser191 amino acid residue in the active site of monomer B. The proton of the hydroxyl group of compound 1 can enter into a hydrogen bond with the oxygen atom of Ala80 in the active site of monomer B. The presence of the five-membered ring E in the structure of the triterpene core in combination with the hydrophobic center of propene, apparently, allows derivative 1 to penetrate deeper into the hydrophobic pocket of the active site of monomer B, creating conformational opportunities for the interaction of the methanol substituent with Ala80 (Fig. 3). A hydrogen bond with an amino acid residue in the active site significantly reduces the estimated binding energy (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Docking of compounds 1, 8 and 15 in KSHV protease asymmetric monomers binding sites (monomer A (a, c, e, g); monomer B (b, d, f, h). a (−4.004 kcal/mol), b (−8.137 kcal/mol)—dimer disruptor; c, d compound 1; e, f compound 8; g, h compound 15. Noncovalent interactions of molecules are shown by dotted lines: green—hydrogen bonds, purple—stacking and pi-sigma interactions, pink—hydrophobic interactions

Table 4.

KSHV protease asymmetric monomers docking results

| Binding energya, kcal/mol | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ligand | Monomer A | Monomer B |

| Dimer disruptor (4P3H) | −4.004 | −8.137 |

| 1 | −5.350 | −7.244 |

| 8 | −4.491 | −5.185 |

| 15 | −4.372 | −5.641 |

aValue is not genuine binding energy but estimated docking score

Molecular modeling shows that hydrophobic structures of azepanbetulin derivatives are theoretically capable of entering the allosteric sites of herpes viral protease dimerization, blocking dimer assembly and inhibiting its function. According to the authors of the KSHV protease XRD model [56], dimer disruptors were the least effective against herpes viruses of the alpha family. This fact can confirm the absence of a pronounced antiviral effect of azepanbetulin derivatives against the herpes simplex virus.

Experimental

General

The spectra were recorded at the Center for the Collective Use “Chemistry” of the Ufa Institute of Chemistry of the UFRC RAS and RCCU “Agidel” of the UFRC RAS. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a “Bruker AM-500” (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA, 500 and 125.5 MHz, respectively, δ, ppm, Hz) in CDCl3, internal standard tetramethylsilane. Mass spectra were obtained on a liquid chromatograph–mass spectrometer LCMS-2010 EV (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Melting points were detected on a micro table “Rapido PHMK05” (Nagema, Dresden, Germany). Optical rotations were measured on a polarimeter “PerkinElmer 241 MC” (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) in a tube length of 1 dm. Elemental analysis was performed on a Euro EA-3000 CHNS analyzer (Eurovector, Milan, Italy); the main standard is acetanilide. Thin-layer chromatography analyses were performed on Sorbfil plates (Sorbpolimer, Krasnodar, Russian Federation), using the solvent system chloroform-ethyl acetate, 40:1. Substances were detected by 10% H2SO4 with subsequent heating to 100–120 °C for 2–3 min. Compounds 1, 2 [57], 3, 17–20 [24], 4, 6, 9, 11, 12, 15, 16, 22, 23 [58], 5 [31], 7 [59], 8, 13 [22], 10, 21 [30], 14 [60], 25 [61], 28 [62], and 35 [63] were prepared by the literature methods. Oleanolic acid 27 was purchased from Xian RongSheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

Chemistry

3-Deoxo-3а-homo-17-(imidazolino)-3а-aza-lup-20(29)-en-carboxamide (24)

To a solution of 1 mmol (0.47 g) compound 23 in dry CH2Cl2 (20 ml) 1 mmol (0.09 ml) (COCl)2 and three drops of Et3N were added, the mixture was stirred for 3 h at 22 °C, organic solvent was removed in vacuum. A solution of freshly prepared 1 mmol A-azepanobetulinic acid chloride in dry CH2Cl2 (20 ml) was treated with 1.3 mmol (0.09 g) imidazole and a catalytic amount of DMAP with the following reflux during 3 h. On completion of the reaction the mixture washed with 5% HCl solution (2×100 ml) and H2O (100 ml), dried over CaCl2, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Then a mixture of crude derivative (1 mmol) and 2.2 mmol (0.07 g) LiAlH4 in dry THF (20 ml) was refluxed for 1 h, after cooling H2O (20 ml) and 10% HCl (10 ml) were added dropwise. The mixture was extracted with CHCl3 (3 × 20 ml), the organic layer was washed with water and dried over CaCl2. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the residue was purified by column with Al2O3; the product was successively eluted chloroform, and a chloroform-ethanol mixture (50:1). Yield (0.41 g, 82%), m.p. 261-263 °С, [α]D20 + 18° (с 0.003, CHCl3); δH (500.13 MHz, CDCl3) 0.89 (s, 3H, H25), 0.92 (s, 3H, H27), 1.14 (s, 3H, H26), 1.39 (s, 3H, H24), 1.48 (s, 3H, H23), 1.59 (s, 3H, H30), 1.17-1.40 (m, 12Н), 1.50-2.30 (m, 14Н), 2.89-3.37 (m, 2H, H19, NH), 4.61 (br.s, 1H, H29a), 4.75 (br.s, 1H, H29b), 7.02 (s, 1H, CH), 7.28 (s, 1H, CH), 7.52 (s, 1H, CH). δC (125.76 MHz, CDCl3) 14.8, 16.1, 19.3, 21.3, 21.8, 22.7, 26.9, 27.9, 28.0, 29.0, 30.6, 33.0, 34.0, 36.9, 37.6, 39.4, 40.9, 41.3, 42.4, 42.9, 45.0, 48.5, 51.3, 54.7, 57.9, 59.9, 63.2, 109.7, 117.5, 128.9, 137.2, 150.2, 172.6. MS (APCI) m/z 504.79 [M − H]− (calcd for C33H51N3O, 505.79). Anal. Calcd for C33H51N3O: C, 78.37; H, 10.16; N, 8.31. Found: C, 78.39; H, 10.17; N, 8.27.

3-Deoxy-3a-homo-17β-(4-pyridinoylhydrazinocarbonyl)-3a-aza-urs-12(13)-en (26)

To a solution of 1 mmol (0.47 g) compound 25 in dry CH2Cl2 (20 ml) 1 mmol (0.09 ml) (COCl)2 and three drops of Et3N were added, the mixture was stirred for 3 h at 22 °C, organic solvent was removed in vacuum. A solution of 1 mmol (0.49 g) freshly prepared acid chloride in dry CH2Cl2 (20 ml) was treated with the 1.3 mmol (0.18 g) 4-pyridinoylhydrazide with following reflux during 3 h. On completion of the reaction the mixture washed with 5% HCl solution (2 × 100 ml) and H2O (100 ml), dried over CaCl2, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Then to a solution of 1 mmol crude derivative in dry THF (20 ml) 2.2 mmol (0.07 g) LiAlH4 was added, and the mixture was refluxed for 1 h, then H2O (20 ml) and 10% HCl (10 ml) were added dropwise. The mixture was extracted with CHCl3 (3 × 20 ml), filtered, the organic layer was washed with water and dried over CaCl2. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the residue was purified by column with Al2O3; the product was successively eluted chloroform, and a chloroform-ethanol mixture (50:1, 25:1). Yield 0.41 g (72%); m.p. 121–124 °С; [α]D20 + 36° (с 0.05, CHCl3); δH (500.13 MHz, CDCl3) 0.76, 0.91, 0.99, 1.02, 1.05, 1.15, 1.22 (7 s, 21H, 7CH3), 1.25–2.65 (m, 25H, CH, CH2), 5.25 (br.s., 1H, H-12), 6.51 (br.s., 3H, 3NH), 7.74 (m, 2H, CH), 8.87 (m, 2H, CH); δC (125.76 MHz, CDCl3) 15.1, 15.2, 16.8, 17.1, 21.9, 23.4, 23.7, 24.1, 26.4, 27.9, 30.7, 31.5, 32.7, 34.1, 36.7, 37.5, 38.8, 39.1, 40.7, 42.2, 47.3, 47.9, 52.6, 55.2, 56.6, 63.2, 66.7, 120.9, 125.5, 128.3, 138.0, 138.5, 150.4, 150.9, 177.7 (NHCO), 182.5 (CONH); MS (APCI) m/z 575.85 [M + H]+ (calcd for C36H54N4O2, 574.85). Anal. Calcd for C36H54N4O2: C, 75.22; H, 9.47; N, 9.75. Found: C, 75.80; H, 9.40; N, 10.03.

Synthesis of compounds (29–31)

To a solution of 1 mmol (0.45 g) compound 27 or 1 mmol (0.45 g) compound 28 in dry CH2Cl2 (20 ml) 1 mmol (0.09 ml) (COCl)2 and three drops of Et3N were added, the mixture was stirred for 3 h at 22 °C, organic solvent was removed in vacuum. A solution of 1 mmol freshly prepared corresponding acid chloride in dry CH2Cl2 (20 ml) was treated with the 1.3 mmol (0.18 g) 4-pyridinoylhydrazide (synthesis of compounds 29 and 30) or 1.3 mmol (0.18 g) 3-pyridinoylhydrazide (synthesis of compound 31) with following reflux during 3 h. On completion of the reactions the solvent was evaporated in vacuum, the residues were washed with water, dried and then purified by column chromatography eluting by chloroform and chloroform–methanol (50:1).

3β-Hydroxy-17β-(4-pyridinoylhydrazinocarbonyl)-olean-12(13)-en (29)

Yield 0.46 g (76%); m.p. 198–200 °С; [α]D20 + 29° (с 0.05, CHCl3); δH (500.13 MHz, CDCl3) 00.77, 0.88, 0.99, 1.02, 1.05, 1.15, 1.21 (7 s, 21H, 7CH3), 1.22–2.82 (m, 23H, CH, CH2), 5.47 (br.s., 1H, H-12), 7.66 (d, 2J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, CH), 8.64 (d, 2J = 5.8 Hz, 2H, CH), 9.23 (br.s., 2H, 2NH); δC (125.76 MHz, CDCl3) 15.1, 15.2, 16.2, 19.4, 19.5, 21.5, 23.5, 23.6, 23.8, 25.7, 26.3, 27.2, 30.7, 31.8, 32.4, 32.9, 33.9, 34.1, 36.6, 39.1, 39.3, 41.3, 41.9, 46.1, 46.8, 47.4, 55.2, 121.2, 123.8, 128.3, 138.4, 143.7, 150.4, 161.9 (NHCO), 174.7 (CONH); MS (APCI) m/z 576.85 [M + H]+ (calcd for C36H53N3O3, 575.84). Anal. Calcd for C36H53N3O3: C, 75.09; H, 9.28; N, 7.30. Found: C, 74.89; H, 9.11; N, 7.53.

3-Oxo-17β-(4-pyridinoylhydrazinocarbonyl)-olean-12(13)-en (30)

Yield 0.47 g (78%); m.p. 166–168 °С; [α]D20 + 23° (с 0.05, CHCl3); δH (500.13 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.76, 0.89, 0.99, 1.01, 1.05, 1.15, 1.21 (7 s, 21H, 7CH3), 1.22–2.82 (m, 23H, CH, CH2), 5.47 (br.s., 1H, H-12), 7.67 (d, 2J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, CH), 8.63 (d, 2J = 5.8 Hz, 2H, CH), 9.21 (br.s., 2H, 2NH); δC (125.76 MHz, CDCl3) 15.1, 15.3, 16.2, 19.4, 19.5, 21.4, 23.5, 23.6, 23.8, 25.7, 26.3, 27.2, 30.7, 31.8, 32.4, 32.9, 33.9, 34.1, 36.6, 39.1, 39.3, 41.3, 41.9, 46.1, 46.8, 47.4, 55.2, 121.2, 123.8, 128.3, 138.5, 143.7, 150.5, 161.9 (NHCO), 174.7 (CONH), 217.4 (C=O); MS (APCI) m/z 574.82 [M + H]+ (calcd for C36H51N3O3, 573.82). Anal. Calcd for C36H51N3O3: C, 75.35; H, 8.96; N, 7.32. Found: C, 75.38; H, 9.00; N, 7.30.

3-Oxo-17β-(3-pyridinoylhydrazinocarbonyl)-olean-12(13)-en (31)

Yield 0.44 g (73%); m.p. 158–160 °С; [α]D20 + 34° (с 0.05, CHCl3); δH (500.13 MHz, CDCl3) 0.62, 0.76, 0.89, 0.99, 1.04, 1.16, 1.19 (7 s, 21H, 7CH3), 1.20-2.79 (m, 23H, CH, CH2), 5.53 (br.s., 1H, H-12), 7.38 (m, 1H, CH), 8.18 (m, 1H, CH), 8.63 (m, 1H, CH), 9.21 (m, 1H, CH), 10.71 (br.s., 2H, 2NH); δC (125.76 MHz, CDCl3) 15.1, 16.2, 19.5, 21.5, 23.5, 23.7, 23.8, 25.7, 26.3, 27.3, 30.7, 31.8, 32.1, 32.9, 33.9, 34.1, 36.6, 39.2, 39.3, 41.5, 42.0, 46.1, 46.2, 46.8, 47.5, 55.2, 123.3, 123.9, 127.4, 135.2, 143.8, 148.7, 152.6, 161.6 (NHCO), 174.0 (CONH), 217.5 (C=O); MS (APCI) m/z 574.82 [M + H]+ (calcd for C36H51N3O3, 573.82). Anal. Calcd for C36H51N3O3: C, 75.35; H, 8.96; N, 7.32. Found: C, 75.40; H, 9.05; N, 7.28.

3-Deoxy-3a-homo-30-О-p-toluenesulfonyl-3a-aza-olean-12(13)-en (32)

A mixture of 1 mmol (0.43 g) compound 15, 1.5 mmol (0.29 g) p-toluenesulfonyl chloride and a catalytic amount of DMAP in anhydrous pyridine (30 ml) were stirred for 48 h at room temperature and poured into a 5% HCl solution (100 ml). The precipitate was filtered, washed with water, dried, and chromatographed on a column with Al2O3; the product was successively eluted with chloroform and a chloroform-ethanol mixture (50:1, 40:1). Yield 0.52 g (88%); m.p. 140–146 °С; [α]D20 + 23° (с 0.05, CHCl3); δH (500.13 MHz, CDCl3) 0.69, 0.72, 1.05, 1.13, 1.21, 1.41, 1.49 (7 s, 21H, 7CH3), 0.92-2.12 (m, 21H, CH and CH2), 2.42 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.89 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.21 (m, 2H, CH2), 3. 63 (br. s, 1H, NH), 3.81–3.89 (m, 1H, CH2), 3.70–3.81 (m, 1H, CH2), 5.15 (br.s., 1H, H-12), 7.35 (m, 2H, CH), 7.75 (m, 2H, CH); δC (125.76 MHz, CDCl3) 16.1, 17.1, 18.4, 19.9, 20.7, 23.6, 24.3, 25.2, 25.4, 25.8, 27.1, 27.5, 28.0, 28.3, 29.4, 29.5, 32.3, 35.4, 35.9, 37.4, 40.1, 40.3, 41.2, 42.5, 44.1, 46.6, 50.8, 54.5, 73.9, 123.1, 127.9, 127.9, 129.8, 129.9, 132.9, 143.3, 144.6. MS (APCI) m/z 596.93 [M + H]+ (calcd for C37H57NO3S, 595.93). Anal. Calcd for C37H57NO3S: C, 74.57; H, 9.64; N, 2.35; S, 5,38. Found: C, 73.71; H, 9.87; N, 2.32; S 5.42.

3-Deoxy-3а-homo-3а-aza-lup-20(29)-en-28-al (33)

To a mixture of 1 mmol (0.43 g) compound 1 in 50 ml CH2Cl2 1 mmol (0.02 g) PCC was added. The mixture was stirred for 30 min at 25 °С, and then quenched by the addition of 9 ml MeOH, the resulting mixture was left for a while and then washed with dry ether and filtered. The solvent was removed and the residue was purified by column chromatography eluting by chloroform and chloroform–ethanol (50:1). Yield 0.32 g (73%); m.p. 266–268 °С, [α]D20 + 55° (с 0.1, CHCl3); δH (500.13 MHz, CDCl3) 0.80, 1.11, 1.20, 1.25, 1.30, 1.70 (6 s, 18H, 6CH3), 1.80–2.50 (m, 26Н), 3.30 (br. s., 2Н, Н3), 4.60 (s, 1Н, Н29b), 4.70 (s, 1Н, Н29а), 9.65 (br.s., 1Н, CHO); δC (125.76 MHz, CDCl3) 13.9, 16.3, 16.3, 19.4, 19.9, 21.8, 22.2, 25.3, 26.1, 26.9, 27.4, 28.3, 29.1, 33.4, 34.2, 34.5, 34.6, 36.8, 38.9, 39.5, 40.8, 41.1, 42.2, 42.9, 46.7, 54.4, 63.1, 110.2, 149.4, 206.4 (CHO). MS (APCI) m/z 440.73 [M + H]+ (calcd for C30H49NO, 439.73). Anal. Calcd for C30H49NO: C, 81.94; H, 11.23; N, 3.19 %. Found: C, 81.95; H, 11.22; N, 3.19.

3-Deoxy-3а-homo-3а-aza-28-(4-pyridinoylhydrazono)-lup-20(29)-en (34)

A solution of 1 mmol (0.44 g) compound 33 and 1.3 mmol (0.18 g) 4-pyridinoylhydrazide in 25 ml MeOH was stirred for 8 h, and then poured into 100 ml 5% HCl. The precipitate was filtered, washed with H2O and dried. The residue was purified by column chromatography eluting by chloroform and chloroform–ethanol (50:1). Yield 0.38 g (69%), m.p. 185–187 °С, [α]D20 + 35° (с 0.003, CHCl3); δH (500.13 MHz, CDCl3) 0.70, 0.85, 0.98, 1.01, 1.10, 1.90 (6 s, 18H, 6CH3), 1.70-2.70 (m, 25Н, CH, CH2), 2.95 (br.s., 1H, H3), 3.25 (br.s., 1H, H19), 4.55 (s, 1H, H29a), 4.65 (s, 1Н, H29b), 7.55 (br.s., 1H, H28), 7.85 (br. s, 2H, CH), 8.78 (br. s, 2H, CH), 10.05 (s, 2H, 2NH); δC (125.76 MHz, CDCl3) 15.7, 16.3, 18.1, 19.3, 22.7, 23.3, 25.7, 26.2, 27.7, 28.6, 29.7, 30.7, 31.9, 33.5, 37.2, 38.6, 39.9, 40.8, 41.2, 42.7, 46.9, 47.5, 48.0, 49.0, 54.2, 56.5, 62.3, 109.4, 121.1, 123.4, 139.8, 149.3, 150.4, 150.9, 161.9 (NHCO), 166.0 (CH=N). MS (APCI) m/z 559.76 [M + H]+ (calcd for C36H54N4O, 558.86). Anal. Calcd for C36H54N4O: C, 77.37; H, 9.74; N, 10.03. Found: C, 77.39; H, 9.74; N, 10.04.

Synthesis of compounds (36, 37)

To a solution of 1 mmol (0.44 g) aldehyde 35 in dry MeOH (60 ml) 2.0 mmol (0.28 g) 3-pyridinoylhydrazide was added, the mixture was stirred 6 h, then poured into H2O (100 ml). The precipitate was filtered, washed with water and dried. The crude product was purified by column chromatography eluting by chloroform and chloroform–ethanol (50:1).

3-Oxo-28-(4-pyridinoylhydrazono)-lup-20(29)-en (36)

Yield 0.37 g (65%); m.p. 164–167 °С, [α]D20 + 55° (с 0.1, CHCl3); δH (500.13 MHz, CDCl3) 0.79, 0.99, 1.00, 1.17, 1.25, 1.65 (6 s, 18H, 6CH3), 1.10–2.80 (m, 25Н, CH, CH2), 4.50 (s, 1Н, H29a), 4.65 (s, 1Н, H29b), 7.25 (br. s, 1H, H28), 7.99 (m, 1H, CH), 8.25 (m, 1H, CH), 8.67 (m, 1H, CH), 9.15 (m, 1H, CH), 10.60 (br.s, 1H, NH); δC (125.76 MHz, CDCl3) 14.5, 15.9, 19.0, 19.6, 21.0, 25.1, 26.6, 27.9, 29.7, 32.3, 33.4, 34.1, 36.8, 38.3, 38.8, 39.5, 40.7, 42.8, 47.3, 47.9, 48.3, 49.1, 49.3, 49.6, 51.1, 54.7, 110.2, 122.6, 129.5, 137.5, 149.6, 153.5, 158.6, 161.9 (CH=N), 168.3 (NHCO), 218.5 (C=O). MS (APCI) m/z 558.82 [M + H]+ (calcd for C36H51N3O2, 557.82). Anal. Calcd for C36H51N3O2: C, 77.51; H, 9.22; N, 7.53. Found: C, 77.55; H, 9.25; N, 7.58.

3,28-Di-(4-pyridinoylhydrazono)-lup-20(29)-en (37)

Yield 0.05 g (7%); m.p. 168–170 °С, [α]D20 + 45° (с 0.1, CHCl3); δH (500.13 MHz, CDCl3) 0.79, 0.98, 1.00, 1.18, 1.14, 1.66 (6 s, 18H, 6CH3), 1.12–2.80 (m, 25Н, CH, CH2), 4.50 (s, 1Н, H29a), 4.65 (s, 1Н, H29b), 7.25 (br. s, 1H, H28), 7.99 (m, 2H, CH), 8.35 (m, 2H, CH), 8.67 (m, 2H, CH), 9.20 (m, 2H, CH), 10.99 (br.s, 2H, 2NH); δC (125.76 MHz, CDCl3) 14.5, 15.7, 19.0, 19.5, 21.2, 25.1, 26.6, 27.9, 29.7, 32.4, 33.5, 34.1, 36.7, 36.9, 38.3, 38.8, 39.5, 40.7, 42.8, 47.3, 47.9, 48.3, 49.1, 49.3, 49.6, 50.8, 54.9, 110.2, 122.6, 123.6, 128.3, 129.4, 136.3, 137.5, 148.1, 149.6, 150.7, 151.8, 153.4, 158.6 (CH=N), 161.9 (C=N), 168.2 (NHCO). MS (APCI) m/z 677.95 [M + H]+ (calcd for C42H56N6O2, 676.95). Anal. Calcd for C42H56N6O2: C, 74.52; H, 8.34; N, 12.41. Found: C, 74.60; H, 8.40; N, 12.40.

Biology

All biology experimental procedures and molecular modeling methods are described in the Supplementary materials.

Conclusions

Thus, we have synthesized a series of semisynthetic triterpenoids bearing A-azepano-, A-seco-3-amino-, and hydrazido/hydrazono fragments and their antimicrobial activity against key ESKAPE pathogens and DNA viruses was evaluated. Azepanobetulinic acid cyclohexyl amide 4 displayed good antibacterial activity that exceeds the effect of the clinically used antibiotic vancomycin, low cytotoxicity to HEK-293 and selectivity index SI 133 even at a maximum tested concentration of >10 μM and hence showed greatest potential for further investigations as noncytotoxic anti-MRSA agent. Azepanobetulin 1, azepanouvaol 8, and azepano-glycyrrhetol 15 showed high potency towards HCMV (EC50 0.15; 0.11; 0.11 µM) with selectivity indexes SI50 115; 136; 172, respectively. The docking studies suggest the possible interactions of the leading compounds with the molecular targets.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Federal program AAAA-A20-120012090023-8. The study of antiviral activity was funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under contract HHSN272201100016I (MNP). The antimicrobial screening was performed by CO-ADD (The Community for Antimicrobial Drug Discovery), funded by the Wellcome Trust (UK) and The University of Queensland (Australia).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41429-021-00448-9.

References

- 1.Owens RC., Jr Antimicrobial stewardship: concepts and strategies in the 21st century. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;61:110–28. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdf?ua=1.

- 3.Cappiello F, Loredo MR, Del Plato C, Cammarone S, Casciaro B, Quaglio D, et al. The revaluation of plant-derived terpenes to fight antibiotic-resistant infections. Antibiotics. 2020;9:325. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anand U, Jacobo-Herrera N, Altemimi A, Lakhssassi N. A comprehensive review on medicinal plants as antimicrobial therapeutics: Potential avenues of biocompatible drug discovery. Metabolites. 2019;9:258. doi: 10.3390/metabo9110258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wozniak L, Skapska S, Marszalek K. Ursolic acid-A pentacyclic triterpenoid with a wide spectrum of pharmacological activities. Molecules. 2015;20:20614–41. doi: 10.3390/molecules201119721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calixto JB. The role of natural products in modern drug discovery. Acad Bras Cienc. 2019;91:e20190105. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201920190105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bucar F, Wube A, Schmid M. Natural product isolation-how to get from biological material to pure compounds. Nat Prod Rep. 2013;30:525–45. doi: 10.1039/c3np20106f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tolstikov GA, Flekhter OB, Shul’ts EE, Baltina LA, Tolstikov AG. Betulin and its derivatives. Chemistry and biological activity. Khim Interes Ustoich Razvit (Chem Sustain Dev) 2005;13:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tolstikova TG, Sorokina IV, Tolstikov GA, Tolstikov AG, Flechter OB. Biological activity and pharmacological prospects of Lupane Terpenoids: I. Natural Lupane derivatives. Russ J Bioorg Chem. 2006;32:37–49. doi: 10.1134/S1068162006010031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krasutsky PA. Birch bark research and development. Nat Prod Rep. 2006;23:919–42. doi: 10.1039/b606816b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Csuk R. Betulinic acid and its derivatives: a patent review (2008-2013) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2014;24:913–23. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2014.927441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sousa JLC, Freire CSR, Silvestre AJD, Silva AMS. Recent developments in the functionalization of betulinic acid and its natural analogues: a route to new bioactive compounds. Molecules. 2019;24:355. doi: 10.3390/molecules24020355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bildziukevich U, Özdemir Z, Wimmer Z. Recent achievements in medicinal and supramolecular chemistry of betulinic acid and its derivatives. Molecules. 2019;24:3546. doi: 10.3390/molecules24193546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung PY, Navaratnam P, Chung LY. Synergistic antimicrobial activity between pentacyclic triterpenoids and antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus strains. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2011;10:25. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-10-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibbons S. Anti-staphylococcal plant natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:263–77. doi: 10.1039/b212695h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang CM, Chen HT, Wu ZY, Jhan YL, Shyu CL, Chou CH. Antibacterial and synergistic activity of pentacyclic triterpenoids isolated from Alstonia scholaris. Molecules. 2016;21:139. doi: 10.3390/molecules21020139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujioka T, Kashiwada Y, Kilkuskie RE, Cosentino LM, Ballas LM, Jiang JB, et al. Anti-AIDS agents, 11. Betulinic acid and platanic acid as anti-HIV principles from Syzigium claviflorum, and the anti-HIV activity of structurally related triterpenoids. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:243–47. doi: 10.1021/np50104a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayaux JF, Bousseau A, Pauwels R, Huet T, Henin Y, Dereu N, et al. Triterpene derivatives that block entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3564–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cinatl J, Morgenstern B, Bauer G, Chandra P, Rabenau H, Doerr HW. Glycyrrhizin, an active component of liquorice roots, and replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Lancet. 2003;361:2045–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13615-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu F, Wang Q, Zhang Z, Peng Y, Qiu Y, Shi Y, et al. Development of oleanane-type triterpenes as a new class of HCV entry inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2013;56:4300–19. doi: 10.1021/jm301910a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Si LL, Meng K, Tian ZY, Sun JQ, Li HQ, Zhang ZW, et al. Triterpenoids manipulate a broad range of virus-host fusion via wrapping the HR2 domain prevalent in viral envelopes. Sci Adv. 2018;4:eaau8408. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau8408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medvedeva NI, Kazakova OB, Lopatina TV, Smirnova IE, Giniyatullina GV, Baikova IP, et al. Synthesis and antimycobacterial activity of triterpeniс A-ring azepanes. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;143:464–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazakova OB, Lopatina TV, Baikova IP, Zileeva ZR, Vakhitova YV, Suponitsky KYU. Synthesis, evaluation of cytotoxicity, and antimicrobial activity of A-azepano- and A-seco-3-amino-C28-aminolupanes. Med Chem Res. 2020;29:1507–19. doi: 10.1007/s00044-020-02577-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kazakova OB, Medvedeva NI, Smirnova IE, Lopatina TV, Veselovsky AV. The introduction of hydrazone, hydrazide, or azepane moieties to the triterpenoid core enhances an activity against M. tuberculosis. Med Chem. 2020;16:1–12. doi: 10.2174/1573406416666200115161700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kazakova OB, Medvedeva NI, Samoilova IA, Baikova IP, Tolstikov GA, Kataev VE, et al. Conjugates of several lupane, oleanane, and ursane triterpenoids with the antituberculosis drug isoniazid and pyridinecarboxaldehydes. Chem Nat Compd. 2011;47:752–58. doi: 10.1007/s10600-011-0050-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown ED, Wright GD. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature. 2016;529:336–43. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Antibiotic resistance. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/antibiotic-resistance/en/.

- 28.Osbourn AE, Lanzotti V. Plant-derived natural products. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2009. p. 361–84. 10.1007/978-0-387-85498-4.

- 29.Subramani R, Narayanasamy M, Feussner KD. Plant-derived antimicrobials to fight against multi-drugresistant human pathogens. Biotech. 2017;7:172. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0848-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kazakova OB, Brunel JM, Khusnutdinova EF, Negrel S, Giniyatullina GV, Lopatina TV, et al. A-ring modified triterpenoids and their spermidine-aldimines with strong antibacterial activity. Molbank. 2019;M1078. 10.3390/M1078

- 31.Kazakova O, Lopatina T, Giniyatullina G, Mioc M, Soica C. Antimycobacterial activity of azepanobetulin and its derivative: In vitro, in vivo, ADMET and docking studies. Bioorg Chem. 2020;104:104209. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao S, Tian Z, Wang Y, Si L, Zhang L, Zhou D. Recent progress in the antiviral activity and mechanism study of pentacyclic triterpenoids and their derivatives. Med Res Rev. 2018;38:951–76. doi: 10.1002/med.21484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee KH. Discovery and development of natural product-derived chemotherapeutic agents based on a medicinal chemistry Approach. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:500–16. doi: 10.1021/np900821e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kashiwada Y, Nagao T, Hashimoto A, Ikeshiro Y, Okabe H, Cosentino LM, et al. Anti-AIDS agents 38. Anti-HIV activity of 3-O-acyl ursolic acid derivatives. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:1619–22. doi: 10.1021/np990633v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng SL, Baglin I, Nour M, Flekhter O, Vita C, Cavé C. Synthesis of ursolic phosphonate derivatives as potential Anti-HIV Agents. Phosph Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem. 2007;182:951–67. doi: 10.1080/10426500601088838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gong Y, Raj KM, Luscombe CA, Gadawski I, Tam T, Chu J, et al. The synergistic effects of betulin with acyclovir against herpes simplex viruses. Antivir Res. 2004;64:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baltina LA, Flekhter OB, Nigmatullina LR, Boreko EI, Pavlova NI, Nikolaeva SN, et al. Lupane triterpenes and derivatives with antiviral activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:3549–52. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00714-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pavlova NI, Savinova OV, Nikolaeva SN, Boreko EI, Flekhter OB. Antiviral activity of betulin, betulinic and betulonic acids against some enveloped and non-enveloped viruses. Fitoterapia. 2003;74:489–92. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(03)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savinova OV, Pavlova NI, Boreko EI. New betulin derivatives in combination with rimantadine for inhibition of influenza virus reproduction. Antibiot Khimioter. 2009;54:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pohjala L, Alakurtti S, Ahola T, Yli-Kauhaluoma J, Tammela P. Betulin-derived compounds as inhibitors of alphavirus replication. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:1917–26. doi: 10.1021/np9003245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karagöza AÇ, Leidenberger M, Hahn F, Hampel F, Friedrich O, Marschall M, et al. Synthesis of new betulinic acid/betulin-derived dimers and hybrids with potent antimalarial and antiviral activities. Bioorg Med Chem. 2019;27:110–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ngoc TD, Moons N, Kim Y, Borggraeve W, Mashentseva A, Andrei G, et al. Synthesis of triterpenoid triazine derivatives from allobetulone and betulonic acid with biological activities. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;13:3292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shah KV, Howley PM. Papillomaviruses. In: Field BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. p. 2077–109.

- 44.Kazakova OB, Giniyatullina GV, Yamansarov EY, Tolstikov GA. Betulin and ursolic acid synthetic derivatives as inhibitors of Papilloma virus. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:4088–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.05.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kazakova OB, Medvedeva NI, Baikova IP, Tolstikov GA, Lopatina TV, Yunusov MS, et al. Synthesis of triterpenoid acylates: Effective reproduction inhibitors of influenza A (H1N1) and papilloma viruses. Russ J Bioorg Chem. 2010;36:771–78. doi: 10.1134/S1068162010060142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khusnutdinova EF, Kazakova OB, Lobov AN, Kukovinets OS, Suponitsky Kyu, Meyers CB, et al. Synthesis of A-ring quinolones, nine-membered oxolactams and spiroindoles by oxidative transformations of 2,3-indolotriterpenoids. Org Biomol Chem. 2019;17:585–97. doi: 10.1039/C8OB02624F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prichard MN, Williams JD, Komazin-Meredith G, Khan AR, Price NB, Jefferson GM, et al. Synthesis and antiviral activities of methylenecyclopropane analogs with 6-alkoxy and 6-alkylthio substitutions that exhibit broad-spectrum antiviral activity against human herpesviruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3518–27. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00429-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smee DF, Huffman JH, Morrison AC, Barnard DL, Sidwell RW. Cyclopentane neuraminidase inhibitors with potent in vitro anti-influenza virus activities. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:743–48. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.743-748.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lahiri SD, Kutschke A, McCormack K, Alm RA. Insights into the mechanism of inhibition of novel bacteria topoisomerase inhibitors from characterization of resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:5278–87. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00571-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Badshah SL, Ullah A. New developments in non-quinolone-based antibiotics for the inhibiton of bacterial gyrase and topoisomerase IV. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;152:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu J, Patel S, Sharma N, Stephen M, Soisson SM, Kishii R, et al. Structures of kibdelomycin bound to Staphylococcus aureus GyrB and ParE showed a novel U-shaped binding mode. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:2023–31. doi: 10.1021/cb5001197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tong L. Viral proteases. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4609–26. doi: 10.1021/cr010184f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao M, Matusick-Kumar L, Hurlburt W, DiTusa SF, Newcomb WW, Brown JC, et al. The protease of herpes simplex virus type 1 is essential for functional capsid formation and viral growth. J Virol. 1994;68:3702–12. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3702-3712.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waxman L, Darke PL. The herpesvirus proteases as targets for antiviral chemotherapy. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2000;11:1–22. doi: 10.1177/095632020001100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lazic A, Goetz DH, Nomura AM, Marnett AB, Craik CS. Substrate modulation of enzyme activity in the herpesvirus protease family. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:913–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gable JE, Lee GM, Jaishankar P, Hearn BR, Waddling CA, Renslo AR, et al. Broad-spectrum allosteric inhibition of herpesvirus proteases. Biochemistry. 2014;53:4648–60. doi: 10.1021/bi5003234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lopatina TV, Medvedeva NI, Baikova IP, Iskhakov AS, Kazakova OB. Synthesis and cytotoxicity of O- and N-acyl derivatives of azepanobetulin. Russ J Bioorg Chem. 2019;45:292–301. doi: 10.1134/S106816201904006X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kazakova O, Smirnova I, Lopatina T, Giniyatullina G, Petrova A, Khusnutdinova E, et al. Synthesis and cholinesterase inhibiting potential of A-ring azepano- and 3-amino-3,4-seco-triterpenoids. Bioorg Chem. 2020;101:104001. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giniyatullina GV, et al. Synthesis and cytotoxicity of N-methylpiperazinylamide azepanobetulinic acid. Nat Prod Comm. 2019;14:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kazakova OB, Rubanik LV, Smirnova IE, Savinova OV, Petrova AV, Poleschuk NN, et al. Synthesis and in vitro activity of oleanane type derivatives against Chlamydia trachomatis. Org Commun. 2019;12:169–75. doi: 10.25135/acg.oc.66.19.07.1352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gnoatto SCB, Dassonville-Klimpt A, Da Nascimento S, Galéra P, Boumediene K, Gosmann G, et al. Evaluation of ursolic acid isolated from IIex paraquariensis and derivatives on inhibition. Eur J Med Chem. 2008;43:1865–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ma CM, Nakamura N, Hattori M. Chemical modification of oleanene type triterpenes and their inhibitory activity against HIV-1 protease dimerization. Chem Pharm Bull. 2000;48:1681–88. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Flekhter OB, Ashavina OY, Boreko EI, Karachurina LT, Pavlova NI, Kabal’nova NN, et al. Synthesis of 3-O-acetylbetulinic and betulonic aldehydes according to svern and the pharmacological activity of related oximes. Pharm Chem J. 2002;36:303. 10.1023/A:1020824506140

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.