Abstract

COVID-19 pandemics has led to genetic diversification of SARS-CoV-2 and the appearance of variants with potential impact in transmissibility and viral escape from acquired immunity. We report a new and highly divergent lineage containing 21 distinctive mutations (10 non-synonymous, eight synonymous, and three substitutions in non-coding regions). The amino acid changes L249S and E484K located at the CTD and RBD of the Spike protein could be of special interest due to their potential biological role in the virus-host relationship. Further studies are required for monitoring the epidemiologic impact of this new lineage.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, lineage, COVID-19, spike, variant of interest

Introduction

COVID-19 continues challenging the health system abroad. After the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in China in late 2019 and despite the rapid international response once the WHO declared it as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), the virus rapidly crossed the borders, started autochthonous transmission in every country and spread locally despite the strict lockdown measures (1). The enormous population size of SARS-CoV-2 at the global level and its RNA nature has led to the rapid accumulation of genetic variability as more than 800 lineages (2, 3). Some lineages or genetic variants have attracted special attention from the beginning of the pandemic spread to date (4, 5), due to their rapid increase in frequency in some areas, abnormally high mutation accumulation across the genome, most amino acid changes affecting the spike protein, evidence for evolutionary convergence of some critical changes and increasing evidence for virus escape to the antibody-mediated immunity (6–9). As genomic information is being deposited in public databases, a growing number of lineages or variants of interest (VOI) and concern (VOC) is being reported (https://github.com/cov-lineages/pango-designation/issues). Interestingly, a very high and increasing number of lineages containing the E484K substitution in the Spike protein have been reported to emerge independently at least 67 times and worldwide (Table 1). This amino acid change located at the RBD of the spike protein has been found to have a negative effect on neutralization by monoclonal antibodies (10), as well as vaccine-induced (11) and polyclonal antibodies resulting from natural infection with circulating lineages (12).

Table 1.

List of lineages and date of emergence of the E484K substitution in the Spike proteina.

| Lineage + 484K | Country of first reported sequence | Earliest collection date | Lineage + 484K | Country of first reported sequence | Earliest collection date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Nigeria | 2021-01-07 | B.1.146 | Brazil | 2021-01-11 |

| A.2 | Spain | 2020-03-31 | B.1.160 | Netherlands | 2020-11-07 |

| A.23.1 | England | 2020-12-26 | B.1.165 | England | 2021-01-08 |

| B.1 | Switzerland | 2020-03-21 | B.1.177 | Switzerland | 2020-09-30 |

| B.1.1 | USA | 2020-12-09 | B.1.177.4 | England | 2020-11-14 |

| B.1.1.1 | England | 2020-06-06 | B.1.2 | Canada | 2020-12-24 |

| B.1.1.10 | England | 2020-12-26 | B.1.214 | Belgium | 2021-01-28 |

| B.1.1.103 | Bangladesh | 2020-12-19 | B.1.234 | USA | 2021-01-14 |

| B.1.1.105 | USA | 2021-01-04 | B.1.235 | Nigeria | 2021-01-08 |

| B.1.1.130 | Russia | 2020-11-17 | B.1.237 | South Africa | 2020-09-16 |

| B.1.1.145 | South Africa | 2020-10-09 | B.1.241 | USA | 2020-07-08 |

| B.1.1.163 | Israel | 2020-12-24 | B.1.243 | USA | 2021-01-18 |

| B.1.1.164 | Australia | 2020-04-16 | B.1.260 | USA | 2021-01-06 |

| B.1.1.184 | Russia | 2020-11-09 | B.1.274 | Kuwait | 2020-12-27 |

| B.1.1.207 | USA | 2020-11-18 | B.1.279 | Canada | 2020-04-20 |

| B.1.1.220 | USA | 2020-12-31 | B.1.280 | USA | 2021-01-14 |

| B.1.1.235 | England | 2020-08-17 | B.1.281 | Bahrain | 2020-11-09 |

| B.1.1.269 | Belgium | 2020-11-10 | B.1.311 | USA | 2021-01-15 |

| B.1.1.273 | South Africa | 2020-10-05 | B.1.316 | England | 2020-11-14 |

| B.1.1.28 | England | 2020-12-08 | B.1.351 | South Africa | 2020-10-08 |

| B.1.1.29 | USA | 2020-12-28 | B.1.369 | USA | 2020-10-06 |

| B.1.1.305 | USA | 2021-02-04 | B.1.400 | USA | 2020-12-10 |

| B.1.1.306 | India | 2020-09-01 | B.1.416 | Gambia | 2020-09-22 |

| B.1.1.316 | Bangladesh | 2021-01-19 | B.1.441 | Egypt | 2021-01-03 |

| B.1.1.33 | Brazil | 2020-11-11 | B.1.486 | USA | 2020-10-22 |

| B.1.1.34 | South Africa | 2020-10-06 | B.1.487 | USA | 2021-01-15 |

| B.1.1.57 | South Africa | 2020-10-09 | B.1.525 | England | 2020-12-15 |

| B.1.1.67 | Singapore | 2021-01-22 | B.1.526 | USA | 2020-12-16 |

| B.1.1.7 | England | 2020-12-17 | C.1 | South Africa | 2020-11-10 |

| B.1.1.74 | England | 2020-04-30 | D.2 | Australia | 2020-10-27 |

| B.1.1.85 | USA | 2021-01-08 | H.1 | South Africa | 2020-12-21 |

| B.1.110.3 | USA | 2020-09-01 | P.1 | Brazil | 2020-12-04 |

| B.1.134 | USA | 2020-08-25 | P.2 | Brazil | 2020-04-15 |

| B.1.139 | USA | 2020-05-22 |

Analysis performed for the sequences available up to February 14, 2021 in GISAID.

In Colombia, SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance was established early during the pandemic, leading to the identification of the importation of at least 12 lineages before international flight cancellation and during lockdown (13). A high percentage (48%) of SARS-CoV-2 sequences were assigned to the B.1 parental lineage with little or no shared mutations accumulated during the early local transmission inside the country. Thereafter, the microevolution of the virus allowed the emergence of some lineages, including the B.1.111 and B.1.420, which were considered Colombian lineages, due to a major representation of sequences from Colombia (37.4 and 85.4%, respectively) in GISAID by February 28, 2021.

Here we report a novel and highly divergent lineage with 21 characteristic mutations, including 10 non-synonymous, eight synonymous and three mutations in non-coding regions (5'and 3' UTR and intergenic region). Further studies are required to assess the functional role of these mutations and to monitor their epidemiologic impact.

Methods

Genomic Surveillance

Genomic surveillance was established at the Sequencing and Genomics Group, National Institute of Health, Colombia (http://www.ins.gov.co/Noticias/Paginas/coronavirus-genoma.aspx). Samples for Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) were selected from routine surveillance in all departments and special groups based on clinical and epidemiologic criteria (14). A total of 287 complete genomes were processed during the period from March 2020 to February 2021. Processing of RNA samples was performed as previously described (13), with the implementation of suggested modifications to the amplicon sequencing protocol (Arctic LoCost) (15) and NGS raw data processing following the protocol described for ONT (https://artic.network/ncov-2019/ncov2019-bioinformatics-sop.html). A dataset including Colombian sequences of SARS-CoV-2 representative of the different lineages and those previously reported in GISAID (Supplementary Table 3) with substitutions of special interest was prepared and used for recombination detection through the RDP4 software (P-values < 0.05) (16), adaptive evolution analysis at the codon level through IFEL and MEME (P-value < 0.3) (17) and phylogenetic analysis.

Lineage Assignment and Phylogenetic Reconstruction

Lineage assignment was performed through the Pangolin algorithm 2 (github.com/cov-lineages/pangolin). p-distance-was calculated for intra-lineage and between-lineages at nucleotide level. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic reconstruction was performed with GTR+F+I nucleotide substitution model using IQTREE (18). Branch support was estimated with an SH-like approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-aLRT) (19).

Results

Four sequences from samples collected in Colombia between December 26, 2020 and January 14, 2021 presented a characteristic mutation pattern, including two amino acid changes in the Spike protein (L249S and E484K). These sequences were originally assigned to the B.1.111 lineage by Pangolin COVID-19 Lineage Assigner (https://pangolin.cog-uk.io/) and currently reassigned to the B.1 lineage (Pango Lineage version: 2021-04-01). The lineage B.1 has been the major basal and widespread lineage from the initial SARS-CoV-2 spread and it became the more prevalent lineage in Colombia (13), while the B.1.111 lineage, first detected in the USA from a sample collected on March 7, 2020 and subsequently in Colombia on March 13, 2020 is currently circulating and mainly represented by Colombian sequences from all around the country (https://microreact.org/project/vHdc5J3MeoYJ2u69PLP6NF).

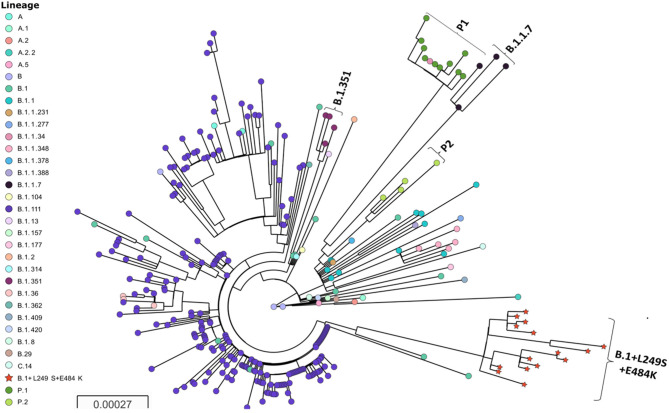

The phylogenetic analysis allowed to identify a highly distant lineage clustering the sequences containing the+L249S and E484K amino acid changes (Figure 1). The inclusion of SARS-CoV-2 sequences representative from the different lineages circulating in Colombia, as well as sequences representative of the major lineages and VOC circulating worldwide allowed to demonstrate the emergence of a novel and phylogenetically distant lineage of SARS-CoV-2 (provisionally named: B.1+L249S+E484K). While it has been detected in several countries, the phylogenetic relationship and the earliest collection date of a sequence belonging to this lineage suggest a recent emergence in ColombiaB.1 was shown to be the more recent common ancestor and therefore the parental lineage, while B.1.111 continues being closely related at the national level. No putative recombination events were detected for the analyzed dataset (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of SARS-CoV-2 and B.1+L249S+E484K emergence. Major lineages circulating in Colombia and representative sequences of the VOC are depicted. The tree was reconstructed by maximum likelihood with the estimated GTR+F+I nucleotide substitution model for the dataset of 304 full-length genomes. The interactive tree can be accessed in the following link: https://microreact.org/project/fTa6f3kY9JraG9NPmQYGog/42c3e045. Red stars represent the sequences belonging to the new lineage.

The large list of distinctive mutations at the nucleotide and protein levels (Table 2) are consistent with the existence of a common recent ancestor for the Colombian sequences and other reported sequences from USA (eight sequences), Aruba (two sequences) and Belgium (one sequence). The B.1+L249S+E484K intra-lineage (0.000208 substitutions per site between each pair of sequences) and between-lineages p-distances (0.000733–0.001918 substitutions per site between each pair of sequences) suggest a drastic divergence of the new lineage from the most closely related lineages (Supplementary Table 2). While increasing the sample size could help to reconstruct the gradual accumulation of mutations leading to divergence from the B.1 ancestor, a plausible explanation for the origin of this highly distant lineage could be the existence of a strong selection pressure on the virus population in an unknown context (e.g., natural infection in a population reaching herd immunity, convalescent plasma or monoclonal antibodies treatment, chronic infection in immunocompromised patients, replication in a different vertebrate species, etc.) (10, 20–22). The result of the analysis by IFEL and MEME, despite the low significance, is suggestive of the presence of a weak but positive selection signal in seven codons, including the previously identified position 614 in the Spike protein (Supplementary Table 3) (23).

Table 2.

Nucleotide and amino acid substitution pattern of the B.1+L249S+E484K putative lineage.

| Genomic coordinates | B.1++L249S+E484K putative lineage substitutions | |

|---|---|---|

| Amino acid change | Region/Protein | |

| C241T | NA | 5'UTR |

| C1060T | Synonymous | NSP2 |

| T5213C | Synonymous | NSP3 |

| C5221T | Synonymous | NSP3 |

| G10523C | V3420L | NSP5 (3C-like proteinase) |

| C16694T | T1076I | NSP13 (Helicase) |

| G17211T | L1248F | NSP13 (Helicase) |

| G17721T | V2365F | NSP13 (Helicase) |

| T21294A | Synonymous | NSP16 (2'-O-ribose methyltransferase) |

| G21295A | Synonymous | NSP16 (2'-O-ribose methyltransferase) |

| G21296A | G2610N | NSP16 (2'-O-ribose methyltransferase) |

| T22308C | L249S | Spike |

| G23012A | E484K | Spike |

| C26681T | Synonymous | Membrane glycoprotein |

| A27253G | I18V | ORF6 protein (Nonstructural protein NS6) |

| C27442T | Synonymous | ORF7a protein (Nonstructural protein NS7a) |

| C27741T | Synonymous | ORF7a protein (Nonstructural protein NS7a) |

| G27798T | A15S | ORF7b protein (Nonstructural protein NS7b) |

| A28272T | NA | Intergenic |

| C28887T | T205I | Nucleocapsid phosphoprotein |

| G29781T | NA | 3'UTR |

Discussion

Genomic surveillance in real time is critical for the identification of genetic changes that could be potentially associated to the epidemiologic and clinical behavior during COVID-19 pandemic. Several VOC and VOI are being described from the end of 2020 to date. VOC are characterized by very high number of mutations located at the Spike protein, whose evidence of biological significance started to accumulate. In the present study, the emerging lineage is bearing the amino acid change E484K, located at the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the Spike protein. This change is of special relevance as it has been associated to the phenotypic properties of some well-described VOC and several VOI (4, 7–9). E484K has been suggested to be responsible for a considerably lower neutralizing activity in vitro from convalescent plasma (20, 24, 25), although the cell-mediated immunity could not be affected by the distinctive mutations (26). In the same way, despite it has not been considered a critical amino acid change, S249L is located at the N-terminal domain (NTD), the second domain most frequently targeted by neutralizing antibodies (25). The potential impact of E484K in concert with other amino acid chances has been suggested for the P.1 variant (8), therefore, its effect in combination to S249L or other changes in critical proteins for viral replication (e.g., Helicase, 2'-O-ribose methyltransferase, etc.) found in the here reported lineage is to be determined.

Despite increasing effort in the routine genomic surveillance in Colombia, the new lineage has only been detected from samples collected during late December to mid-January mainly from the Caribbean region of the country, which supposes a major effort is necessary to determine the epidemiologic contribution and potential expansion in the different cities.

An obligatory question that arises from the current analysis of the novel lineage and the evidence of 67 other lineages with the evolutionary convergence at the Spike E484K is related to the context of the emergence of highly divergent lineages, and the selection of specific substitutions. The fact that some amino acid changes have appeared independently in these lineages is not plausibly explained by chance, but probably by the result of a selective immune pressure. Many hypotheses have been raised without conclusive support. One of them is related to the chronic infection in immunocompromised patients and the administration of under-neutralizing antibody titers during convalescent plasma or monoclonal antibody therapies (21, 22, 27, 28) also raising questions about the use of immunotherapies for treatment of acutely infected patients.

In the context of pandemic spread of the virus, an enormous virus population size is expected, as it is also the emergence of virus variants that could also make possible the emergence of antibody-resistant mutants in the context of natural infection in immunocompetent people. Therefore, another plausible hypothesis for the emergence of neutralization escape mutants could be the fact that several countries and cities approximated to a high seroprevalence during the second semester of 2020 and became more restrictive for transmission of the first wave lineages, privileging the growth of specific lineages with distinctive mutations that allowed the escape to the polyclonal immune response.

It is mandatory to evaluate the impact of the genetic background of B.1+L249S+E484K in the neutralization efficacy of convalescent sera/plasma from acquired immunity.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.gisaid.org/, Full genome SARS-CoV-2 Colombian sequences belonging to the new proposed lineage were deposited in GISAID under accession numbers: EPI_ISL_1092008, EPI_ISL_1092007, EPI_ISL_1092006, and EPI_ISL_1092005.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Comité de Ética y Metodologías de la Investigación–CEMIN, Instituto Nacional de Salud, Bogota, Colombia. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

KL-D and MM-R designed the study and planned the experiments. KL-D, CF-M, DA-D, HR-M, JR-G, DP, SC, MH-S, JN, GS, and MW carried out the experiments. DW, MO, and MM-R supported the epidemiologic aspects of the study. KL-D and JU-C analyzed the data and took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript, contributed to the article, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Laboratory Network for routine virologic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in Colombia. We also thank all researchers who deposited genomes in GISAID's EpiCoV Database contributing to genomic diversity and phylogenetic relationship of SARS-CoV-2. We thank Rotary International and Charlie Rut Castro for equipment's donation. Finally, we thank red RENATA and Universidad Industrial de Santander for the bioinformatic assistance.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was funded by the Project CEMIN-4-2020 Instituto Nacional de Salud. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. JU-C was supported by CONADI grant INV3070 from Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.697605/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Lee K, Worsnop CZ, Grépin KA, Kamradt-Scott A. Global coordination on cross-border travel and trade measures crucial to COVID-19 response. Lancet. (2020) 395:1593–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31032-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GISAID . GISAID initiative. Adv Virus Res. (2020) 2008:1–7. Available online at: https://www.gisaid.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rambaut A, Holmes EC, O'Toole Á, Hill V, McCrone JT, Ruis C, et al. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat Microbiol. (2020) 5:1403–7. 10.1038/s41564-020-0770-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control Prevention C. D. C. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Cent Infect Dis Res Policy. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/scientific-brief-emerging-variants.html (accessed March 2, 2021).

- 5.Volz E, Hill V, McCrone JT, Price A, Jorgensen D, O'Toole Á, et al. Evaluating the effects of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutation D614G on transmissibility and pathogenicity. Cell. (2021) 184:64–75.e11. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rambaut A, Loman N, Pybus O, Barclay W, Barrett J, Carabell A, et al. Preliminary Genomic Characterisation of an Emergent SARS-CoV-2 Lineage in the UK Defined by a Novel Set of Spike Mutations. (2020). Available online at: https://virological.org/t/preliminary-genomic-characterisation-of-an-emergent-sars-cov-2-lineage-in-the-uk-defined-by-a-novel-set-of-spike-mutations/563 (accessed April17, 2021).

- 7.Voloch CM, da Silva Francisco R, Jr, de Almeida LGP, Cardoso CC, Brustolini OJ, Gerber AL, et al. Genomic characterization of a novel SARS-CoV-2 lineage from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Virol. (2021) 1:e00119-21. 10.1128/JVI.00119-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faria NR, Mellan TA, Whittaker C, Claro IM, Candido da DS, Mishra S, et al. Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science. (2021) 372:815–21. 10.1126/science.abh2644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tegally H, Wilkinson E, Giovanetti M, Iranzadeh A, Fonseca V, Giandhari J, et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa. Nature. (2021) 592:438–43. 10.1038/s41586-021-03402-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisblum Y, Schmidt F, Zhang F, DaSilva J, Poston D, Lorenzi JC, et al. Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants. Elife. (2020) 9:e61312. 10.7554/eLife.61312.sa2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Schmidt F, Weisblum Y, Muecksch F, Barnes CO, Finkin S, et al. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature. (2021). 592:616–22 10.1038/s41586-021-03324-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, VanBlargan LA, Bloyet L-M, Rothlauf PW, Chen RE, Stumpf S, et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations that attenuate monoclonal and serum antibody neutralization. Cell Host Microbe. (2021) 29:477–88.e4. 10.1016/j.chom.2021.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laiton-Donato K, Villabona-Arenas CJ, Usme-Ciro JA, Franco-Muñoz C, Álvarez-Díaz DA, Villabona-Arenas LS, et al. Genomic epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Colombia. Emerg Infect Dis. (2020) 26:2854–62. 10.3201/eid2612.202969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Instito Nacional de Salud . Estrategia de Caracterización Genómica SARS-CoV-2, COLOMBIA. 1–12. (2021). Available online at: http://www.ins.gov.co/BibliotecaDigital/Estrategia-de-caracterizacion-genomica-SARS-CoV2_Colombia.pdf (accessed April 18, 2021).

- 15.Tyson JR, James P, Stoddart D, Sparks N, Wickenhagen A, Hall G, et al. Improvements to the ARTIC multiplex PCR method for SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing using nanopore. bioRxiv Prepr Serv Biol [Preprint]. (2020). 10.1101/2020.09.04.283077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, Khoosal A, Muhire B. RDP4: detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. (2015) 1:vev003. 10.1093/ve/vev003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delport W, Poon AFY, Frost SDW, Kosakovsky Pond SL. Datamonkey 2010: a suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics. (2010) 26:2455–7. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. (2015) 32:268–74. 10.1093/molbev/msu300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guindon S, Dufayard J-F, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O, et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. (2010) 59:307–21. 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greaney AJ, Loes AN, Crawford KHD, Starr TN, Malone KD, Chu HY, et al. Comprehensive mapping of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain that affect recognition by polyclonal human plasma antibodies. Cell Host Microbe. (2021) 29:463–76.e6. 10.1016/j.chom.2021.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kemp SA, Collier DA, Datir RP, Ferreira IATM, Gayed S, Jahun A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution during treatment of chronic infection. Nature. (2021) 592:277–82. 10.1038/s41586-021-03291-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rees-Spear C, Muir L, Griffith SA, Heaney J, Aldon Y, Snitselaar JL, et al. The effect of spike mutations on SARS-CoV-2 neutralization. Cell Rep. (2021) 34:108890. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dumonteil E, Herrera C. Polymorphism and selection pressure of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and diagnostic antigens: implications for immune evasion and serologic diagnostic performance. Pathogens. (2020) 9:584. 10.3390/pathogens9070584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cele S, Gazy I, Jackson L, Hwa S-H, Tegally H, Lustig G, et al. Escape of SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 variants from neutralization by convalescent plasma. Nature. (2021) 593:142–6. 10.1038/s41586-021-03471-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wibmer CK, Ayres F, Hermanus T, Madzivhandila M, Kgagudi P, Oosthuysen B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 escapes neutralization by South African COVID-19 donor plasma. Nat Med. (2021) 27:622–5. 10.1101/2021.01.18.427166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarke A, Sidney J, Methot N, Zhang Y, Dan JM, Goodwin B, et al. Negligible impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants on CD4+ and CD8+ T cell reactivity in COVID-19 exposed donors and vaccinees. bioRxiv [Preprint]. (2021) 2021.02.27.433180. 10.1101/2021.02.27.433180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi B, Choudhary MC, Regan J, Sparks JA, Padera RF, Qiu X, et al. Persistence and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an immunocompromised host. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:2291–3. 10.1056/NEJMc2031364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu J, Peng P, Wang K, Fang L, Luo F, Jin A, et al. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants reduce neutralization sensitivity to convalescent sera and monoclonal antibodies. Cell Mol Immunol. (2021) 18:1061–3. 10.1101/2021.01.22.427749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.gisaid.org/, Full genome SARS-CoV-2 Colombian sequences belonging to the new proposed lineage were deposited in GISAID under accession numbers: EPI_ISL_1092008, EPI_ISL_1092007, EPI_ISL_1092006, and EPI_ISL_1092005.