Abstract

Recent models of psychopathology suggest the presence of a general factor capturing the shared variance among all symptoms along with specific psychopathology factors (e.g., internalizing and externalizing). However, few studies have examined predictors that may serve as transdiagnostic risk factors for general psychopathology from early development. In the current study we examine, for the first time, whether observed and parent-reported infant temperament dimensions prospectively predict general psychopathology as well as specific psychopathology dimensions (e.g., internalizing and externalizing) across childhood. In a longitudinal cohort (N = 291), temperament dimensions were assessed at 4 months of age. Psychopathology symptoms were assessed at 7, 9, and 12 years of age. A bifactor model was used to estimate general, internalizing, and externalizing psychopathology factors. Across behavioral observations and parent-reports, higher motor activity in infancy significantly predicted greater general psychopathology in mid to late childhood. Moreover, low positive affect was predictive of the internalizing-specific factor. Other temperament dimensions were not related with any of the psychopathology factors after accounting for the general psychopathology factor. The results of this study suggest that infant motor activity may act as an early indicator of transdiagnostic risk. Our findings inform the etiology of general psychopathology and have implications for the early identification for children at risk for psychopathology.

Keywords: general factor, motor activity, p factor, psychopathology, temperament

Psychiatric disorders tend to co-occur in the same individual (Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, 1999). Towards this end, recent efforts to understand comorbidity among psychiatric disorders have focused on examining the common and unique variation among psychiatric symptoms using continuous dimensions rather than categorical measures of psychopathology. These studies have revealed the presence of a general psychopathology factor, also called the “p factor,” which captures the shared variance among all psychopathology symptoms; residual variance is further clustered into orthogonal internalizing and externalizing factors (Caspi et al., 2014). Although there has been considerable interest in utilizing this transdiagnostic approach to study psychopathology, relatively little longitudinal work has examined early predictors that may serve as transdiagnostic risk factors for general psychopathology (Caspi & Moffitt, 2018). In the current study, we examined whether infant temperament prospectively predicts general psychopathology as well as specific psychopathology dimensions (e.g., internalizing and externalizing) in childhood. Specifically, we employed a multimethod approach to examine whether dimensions of temperament, including individual differences in activity and affectivity (positive and negative affect), in early infancy are longitudinally associated with general or specific psychopathology factors.

In addition to better characterizing the structure of psychopathology, utilizing a transdiagnostic approach to measure psychopathology allows researchers to identify whether risk factors predict commonalities shared across all domains of psychopathology or more specific domains of psychopathology such as internalizing and externalizing problems. Importantly, the general psychopathology factor is unlikely to be the result of methodological artifacts (e.g., measurement bias) as it is associated with substantive and measurement-independent outcomes. For example, the general psychopathology factor exhibits significant genetic contributions (Allegrini et al., 2020; Grotzinger, Cheung, Patterson, Harden, & Tucker-Drob, 2019; Harden et al., 2020; Selzam, Coleman, Caspi, Moffitt, & Plomin, 2018). Moreover, the general psychopathology factor has been related to familial psychiatric risk (Martel et al., 2017), impaired school functioning (Lahey et al., 2015), IQ (Caspi et al., 2014), and lower executive functions (Huang-Pollock, Shapiro, Galloway-Long, & Weigard, 2017; Martel et al., 2017), as well as functional and structural differences in domain-general brain areas underlying the regulation of behavior, thoughts, and emotions (Snyder, Hankin, Sandman, Head, & Davis, 2017). Moreover, the presence of a general psychopathology factor, along with specific factors for internalizing and externalizing, has been reported in studies across childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (Allegrini et al., 2020; Caspi et al., 2014; Hankin et al., 2017; McElroy, Belsky, Carragher, Fearon, & Patalay, 2018; Olino, Dougherty, Bufferd, Carlson, & Klein, 2014, 2018). However, most of the work examining the characteristics associated with the general psychopathology factor in pediatric samples is based on cross-sectional data; much less is known about how early characteristics in infancy and early childhood longitudinally relate to either general psychopathology or specific internalizing and externalizing factors. An improved understanding of how early infant or childhood characteristics predict transdiagnostic risk could inform the etiology of the general psychopathology factor and aid efforts to identify children who might benefit most from interventions.

Temperament in infancy and early childhood is an important early predictor of later psychopathology (Kagan & Fox, 2006; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). While theoretical perspectives on early temperament vary, there is general agreement that temperamental traits are constitutionally based individual differences in activity, affectivity, and self-regulation (or effortful control) that are relatively stable across time (Kagan & Fox, 2006; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Traditionally, specific temperament classifications have been associated with specific psychiatric disorders, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Miller, Degnan, Hane, Fox, & Chronis-Tuscano, 2019), depression (Dougherty, Klein, Durbin, Hayden, & Olino, 2010), and social anxiety disorder (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009). Taking an initial step towards a transdiagnostic approach to psychopathology, prior studies have also examined how temperament relates to the broader classifications of “externalizing” and “internalizing” psychopathology. In general, these studies have found that traits associated with withdrawal in infancy or toddlerhood, such as fear and sadness, are predictive of increased internalizing problems in later childhood (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Morales, Beekman, Blandon, Stifter, & Buss, 2015; Stifter, Putnam, & Jahromi, 2008). In contrast, higher levels of approach-related traits, such as activity level, positive affect, impulsivity, and low effortful control, are longitudinally associated with externalizing problems (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Stifter et al., 2008). Interestingly, some studies have also found that high activity level, high impulsivity, and low effortful control are not only related to externalizing but also to internalizing (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Stifter et al., 2008) or overall behavior problems (De Pauw, Mervielde, & Van Leeuwen, 2009). This suggests that these temperamental dimensions may act as early transdiagnostic risk factors for the development of general psychopathology, as opposed to internalizing or externalizing specifically.

To date, minimal work has directly studied the relations between childhood temperament and latent dimensions of psychopathology, including general psychopathology. Like most other research on general psychopathology in children, existing temperament–psychopathology work has mostly relied on cross-sectional designs and single-method assessments of temperament (most often parent reports). Existing studies find similar relations across childhood (3–17 years), such that general psychopathology is associated with lower effortful control, higher negative affect, and a composite measure of surgency that consists of high activity level, positive affect, impulsivity, and low shyness (Hankin et al., 2017; Olino et al., 2014). Moreover, these studies have also found specific links between temperament and internalizing or externalizing factors. Internalizing factors have been related to higher negative affect and lower surgency, whereas externalizing factors were related to lower effortful control and higher surgency. The only study examining longitudinal associations between socioemotional dispositions and general psychopathology found that parent-rated negative affect in childhood and adolescence (10–17 years) predicted the general psychopathology factor in early adulthood (23–31 years) (Class et al., 2019). In contrast, the only study using behavioral observations of temperament for preschool-age children yielded null concurrent relations with general psychopathology (Olino et al., 2014). Thus, existing work investigating the role of early temperament on later transdiagnostic risk is inconsistent and relations to general psychopathology are limited to parent reports of temperament. This suggests that some of the relations linked to general psychopathology might be due to common-method variance. In the current study, we utilize a multimethod approach, including behavioral observations of temperament to avoid the issue of common-method variance.

Moreover, most previous studies linking temperament and general psychopathology have focused on broader temperament factors such as negative affectivity or surgency. Although these temperament factors are validated and widely used, the combination of multiple temperament dimensions might mask relations with psychopathology. For example, surgency and related temperament factors often include scales that index high levels of activity and impulsivity as well as positive affect and sociability (Degnan et al., 2011; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001). These combined temperament factors might conceal the effects of specific dimensions that predict psychopathology or mask temperamental dimensions that relate to psychopathology in opposite directions (Buss, Kiel, Morales, & Robinson, 2014). As such, in the current study, we examined relations with fine-grained dimensions of temperament (i.e., negative affect, positive affect, and activity levels) rather than broader temperament factors.

We examined whether infant temperament at 4 months of age prospectively predicted general psychopathology as well as specific psychopathology factors capturing internalizing and externalizing during mid to late childhood. We focused on the temperament of infants aged 4 months in an attempt to identify the earliest behavioral transdiagnostic risk factor to date. Longitudinal studies have found considerable developmental stability in the general psychopathology factor from early childhood to adulthood (Class et al., 2019; Greene & Eaton, 2017; McElroy et al., 2018; Murray, Eisner, & Ribeaud, 2016; Olino et al., 2018; Snyder, Young, & Hankin, 2017), highlighting the importance of identifying early factors that may predict increased transdiagnostic risk across development.

The temperament dimensions of motor activity, positive affect, and negative affect can be reliably characterized in young infants via parent reports and behavioral observations (Fox, Henderson, Rubin, Calkins, & Schmidt, 2001; Kagan & Snidman, 1991; Miller et al., 2019; Rothbart, 1981). Importantly, behavioral observations reduce recall and reporting biases and avoid common-method variance as they are independent measures from parent reports of psychopathology (Kagan & Fox, 2006), whereas parent reports provide an efficient and scalable way to assess temperament, which also provides a broader perspective that includes a variety of naturally occurring situations (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Therefore, in the current study, we combined these approaches to obtain a robust multimethod measure of temperament.

Moreover, we focused on psychopathology during school age, as opposed to earlier ages, since the behavioral manifestation of psychopathology may be most evident during school years, with an average age of onset around 7 years (Jones, 2013; Kessler et al., 2007). For instance, many children display moderate to high levels of externalizing and internalizing problems during toddlerhood and preschool. Although many children “outgrow” these behaviors, for some, these problems persist into school age and adolescence, leading to socioemotional problems (Bufferd, Dougherty, Carlson, & Klein, 2011, 2012; Campbell, Spieker, Burchinal, & Poe, 2006; Egger & Angold, 2006).

Based on the above literature review, we predicted that higher infant motor activity, negative affect, or positive affect would all be associated with the general psychopathology factor later in life. Based on the findings of past studies, we further hypothesized that higher negative affect and lower positive affect would be associated with the internalizing-specific factor, whereas higher positive affect and motor activity (i.e., temperament dimensions falling under surgency) would be associated with the externalizing-specific factor. Finally, because there are important differences by gender in both the incidence of psychopathology (Seedat et al., 2009) and the developmental pathways from early temperament to later psychopathology (Miller et al., 2019; Morales et al., 2015, 2019; Rubin, Burgess, Dwyer, & Hastings, 2003), we also explored whether prospective relations between infant temperament and later psychopathology differed by gender. The reason we do not propose specific gender hypotheses is because none of the previous studies examining gender differences in the temperament–psychopathology relation have accounted for the shared variance across disorders.

Method

Participants

In total, 291 participants (135 male, 156 female) were recruited in infancy and screened for infant temperament. To achieve this sample, 779 infants aged 4 months underwent temperament screening in the laboratory. Infants were selected based on their affect (positive and negative) and motor responses to novel visual and auditory stimuli, oversampling for high levels of reactivity to produce a wider range of reactivity compared with a randomly selected community sample. More details on the recruitment and screening procedures are provided elsewhere (Hane, Fox, Henderson, & Marshall, 2008). Based on the initial sample demographics, the mothers were 69.4% Caucasian, 16.5% African American, 7.2% Hispanic, 3.1% Asian, and 3.4% other, with 0.3% missing demographic information. Information on family income was not collected for the sample, but mothers in the sample reported on their level of education: 35.7% were graduate school graduates, 41.9% were college graduates, 16.2% were high school graduates, and 5.5% reported other forms of education; education information was missing for 0.7%. Families continued to participate in multiple assessments of their children’s socioemotional development between the ages of 4 months and 12 years. The current study focused on temperament assessments at age 4 months and parent reports of child psychopathology at school age (7, 9, and 12 years). All families consented to participate in the study, all the procedures of which were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Maryland and the University of Miami.

Measures

Temperament

Observed infant temperament.

At age 4 months, infants were assessed for their degree of reactivity to visual and auditory stimuli, including live presentations of novel toys and auditory presentations of novel sounds (Fox et al., 2001). Infant behavioral reactions to the stimuli were video recorded and coded offline. The videos were coded in 5-s epochs for three main behaviors: motor activity, positive affect, and negative affect. A motor activity score was obtained by summing the frequencies of arm waves, arm wave bursts, leg kicks, leg kick bursts, back arches, and hyperextensions throughout the paradigm. A positive affect score was calculated by summing the frequencies of smiling and positive vocalizations. A negative affect score was obtained by summing the frequencies of fussing and crying. Codes were prorated based on the number of 5-s epochs coded. All coding was completed by four reliable coders, with intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from .80 to .92 (see Hane et al. (2008) for more details). Given that the observed temperament dimensions were non-normally distributed (skewrange = 1.18, 2.51; kurtosisrange = 2.51, −8.87), the scores were log-transformed [log(x + 1)] to improve normality (skewrange = −0.43, −1.68; kurtosisrange = −1.17, 3.57).

Parent-reported infant temperament.

At age 4 months, parents completed the Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ; Rothbart, 1981) to report the temperament of their infants. The IBQ is composed of items that describe the frequency of specific concrete behaviors of infants on a 7-point scale. Items are composited on six temperament dimensions: activity level, smiling and laughter, fear (distress to novelty), distress to limitations, soothability, and duration of orienting. In line with the original report of the IBQ (Rothbart, 1981), all six temperament dimensions demontrated adequate internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .73 to .84. The distributions of the parent-reported temperament dimensions were normally distributed (skewrange = −0.08, 0.87; kurtosisrange = −0.69, 0.59).

Temperament composite.

In order to provide a more comprehensive multimethod measure of temperament, composite measures of temperament were created for positive affect, negative affect, and activity levels by combining behavioral observations and parent reports. Specifically, we first standardized each temperament dimension and then averaged them. We combined observed motor activity and parent reports of activity levels to create a motor activity levels composite; we combined observed positive affect and parent reports of smiling and laughter to create a composite of positive affect; likewise, we combined observed negative affect and parent reports of distress to limitations and fear to create a negative affect composite. We did not use soothability and duration of orienting from the IBQ as they did not have clear parallels with the behavioral observations of temperament. Previous studies have combined behavioral observations and parent reports of temperament to provide a more comprehensive measure of temperament (Penela, Walker, Degnan, Fox, & Henderson, 2015; Troller-Renfree, Buzzell, Pine, Henderson, & Fox, 2019). In addition, as sensitivity analyses, we examined the relations to psychopathology separately for observed and parent reports of temperament, yielding similar results (see Tables S1 and S2 and Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material).

Psychopathology

Children’s problem behaviors were rated by their parents at assessments at age 7 years (meanage = 7.65; SDage = 0.23), 9 years (meanage = 10.14; SDage = 0.38), and 12 years (meanage = 13.14; SDage = 0.63) using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) – a well-validated parent-report questionnaire used to assess the socioemotional functioning of young children – with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .78 to .94 (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). As in previous studies modeling the latent dimensions of psychopathology with the CBCL (e.g., McElroy et al., 2018), we used the scales from the broad externalizing and internalizing dimensions of the CBCL (i.e., Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Rule-Breaking Behavior, and Aggressive Behavior) as well as the Attention Problems scale. Because the distributions of most scales were positively skewed at all ages (skewrange = 0.93, 2.86; kurtosisrange = 0.11, 13.35), scores were transformed by taking the square root to improve normality (skewrange = −0.19, 0.67; kurtosisrange = −1.19, −0.06).

Analyses

As in previous studies examining the structure of psychopathology, we compared a confirmatory correlated factors model and a confirmatory bifactor model across ages 7, 9, and 12 years. The correlated factors model consisted of two latent factors: (a) scores of the Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, and Somatic Complaints scales loaded onto an internalizing factor; (b) the Attention Problems, Rule-Breaking Behavior, and Aggressive Behavior scales loaded onto an externalizing factor. The bifactor model expanded on the correlated factors model with the specific internalizing and externalizing factors to include an additional general psychopathology factor with loadings from all scales.

Previous developmental studies suggest a high degree of stability in psychopathology factors across age, including the age range of the current study (Greene & Eaton, 2017; McElroy et al., 2018; Murray et al., 2016; Olino et al., 2018; Snyder, Young, et al., 2017). As shown in the Supplementary Material (Figure S2), we also observed a high degree of stability in the general psychopathology factor across ages (β > .70) and stability in the relations between temperament and psychopathology factors, which did not differ across age. Thus, as in previous studies examining general psychopathology (Caspi et al., 2014; Lahey et al., 2015), the structure of psychopathology was evaluated across age (i.e., the assessments at 7, 9, and 12 years of age). To account for the age-specific variance that was uncorrelated with the psychopathology factors, the residual covariances within assessments were estimated across all scales for that timepoint. Moreover, in order to account for the repeated measurement of each scale across age, the residual covariances between assessments were estimated for each scale across all time-points. In order to examine the impact of modeling the variance associated with the different assessments in different ways, we also modeled the age-specific variance that was uncorrelated with trait psychopathology as age factors (i.e., ages 7, 9, and 12 years), as also done by Caspi et al. (2014). The results presented below, accounting for age-specific variance by estimating the residual covariances within assessments, did not change when modeling the age-specific variance as separate “Age” factors (see Table S3 in the Supplementary Material). However, not accounting for the age-specific variance (i.e., ignoring the different age assessments) led to a poor model fit.

Models were estimated using the software package Lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) in R using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) to reduce potential bias in the parameter estimates due to missing data (Enders & Bandalos, 2001). This approach allowed the inclusion of all participants with data on one or more variables (as opposed to listwise deletion). To account for departures from multivariate normality in the presence of missing data, models were fit using a maximum likelihood with a robust variance estimator (MLR) (Yuan & Bentler, 2000). A chi-square difference test was used to compare the correlated factors model and the bifactor model using the values of the scaled Satorra–Bentler chi-square statistic appropriate for the MLR (Satorra & Bentler, 2001). Because fit statistics can be biased in favor of bifactor models (Greene et al., 2019) and to help interpret novel relations with general psychopathology by placing them in the same context of previous studies utilizing the correlated factors model, further analyses with temperament were performed with both the correlated factor model and bifactor model.

To examine the relations between the temperament dimensions and psychopathology, we added the temperament dimensions as predictors of the psychopathology factors to the correlated factor model and the bifactor model. Moreover, in line with previous studies with this sample (Miller et al., 2019; Morales et al., 2019), we included gender, maternal education, and maternal ethnicity as covariates to help better estimate missing patterns and because they were associated with some scales of psychopathology (see Table S4 in the Supplementary Material). Gender was coded as males = 0 and females = 1. Maternal ethnicity was coded as non-Hispanic Caucasian = 1 and other = 0 and maternal education was coded as high school graduate = 0, college graduate = 1, graduate school graduate = 2, and other = missing. These covariates were added by also modeling gender, maternal education, and maternal ethnicity as predictors of the psychopathology factors.

For the bifactor model, we estimated the models following the recommendations of Koch, Holtmann, Bohn, & Eid (2018) to provide unbiased prediction estimates of the orthogonal latent factors. Although this was done in two steps (estimating the prediction to the general factor and the specific factors in separate analyses), the results are presented together to simplify their presentation. All exogenous variables (temperament dimensions and covariates) were allowed to covary with each other. To control for the inflation of Type I error rate due to multiple comparisons, we applied the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) with a 0.05 false positive discovery rate (FDR).

To explore gender differences, we further examined each model separately for males and females to evaluate the potential moderating role of gender in the structure of psychopathology as well as gender differences in the relations between infant temperament and childhood psychopathology. Chi-square difference tests were used to compare the models between males and females; if a significant difference across models was found, we conducted follow-up analyses to systematically compare each regression path to determine which path significantly differed between males and females (Satorra & Bentler, 2001).

Results

Preliminary analyses

Of the total sample (N = 291), 230 participants had at least one timepoint with a parent report of psychopathology; 191 had data at age 7 years, 186 had data at age 9 years, and 175 had data at age 12 years. Of these, 83.0% of children had data from at least two ages. As such, we utilized an analytic approach (i.e., FIML) that reduced the potential biases associated with missing data. Finally, children included in the bifactor model (n = 230) did not differ from the rest of the sample in gender (p = .82), maternal education ( p = .33), or any of the temperamental dimensions ( p values > .08). The only exception was maternal ethnicity ( p = .05), such that children with data on these measures of psychopathology were more likely to have non-Hispanic Caucasian mothers than children with missing data. As such, this variable was included in the models (see below). The descriptive statistics and correlations among all the study variables are provided in Table S4 in the Supplementary Material.

Comparison of the bifactor model and correlated factors model

The correlated factors model and the bifactor model were fit as confirmatory factor analyses to examine the structure of psychopathology. The fit indices and factor loadings for both models are presented in the Supplementary Material (Table S5).

The correlated factors model had an adequate fit (comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.99, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.98, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.03, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.04). All symptoms loaded significantly onto the externalizing and internalizing factors. Moreover, the externalizing and internalizing factors were significantly related (b = 0.708, SE = 0.064, p < .001), implying considerable shared variance.

The bifactor model also demonstrated adequate fit (CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.02, SRMR = 0.04). All symptoms loaded significantly onto the general psychopathology factor. The remaining variance of all symptoms loaded significantly onto the specific internalizing and externalizing factors – the only exceptions were aggression at all ages and attention problems at age 12, which did not significantly load onto the externalizing factor while significantly loading onto the general psychopathology factor (Table S5). Of note, the general psychopathology factor demonstrated good reliability (omega = .90 and omega hierarchical = .71). Moreover, the general psychopathology factor explained the majority of the variance, as indicated by the explained common variance (ECV = .65). The specific factors, internalizing and externalizing, explained similar amounts of variance (ECVinternalizing = .19 and ECVexternalizing = .17) and exhibited lower reliability after accounting for the general psychopathology factor (omegainternalizing = .77 and omegaexternalizing = .90; omega hierarchicalinternalizing = .42 and omega hierarchicalexternalizing = .18).

Although both the correlated factors model and the bifactor model demonstrated adequate fit, comparisons of the two models revealed that the bifactor model was a better reflection of the factor structure of psychopathology than the correlated factors model (Δχ2 (11) = 25.34, p = .008). These results support previous literature and the a priori decision to examine temperament differences in psychopathology based on the three factors from the bifactor model (general psychopathology, internalizing, and externalizing). However, we examined the predictive relations of temperament and psychopathology factors using both the bifactor model and the correlated factors model because fit statistics can be biased in favor of bifactor models (Greene et al., 2019). Moreover, showing relations with the correlated factors model as in previous studies can aid the interpretation of novel relations with general psychopathology. Finally, we evaluated potential gender differences in the structure of psychopathology by testing if the models significantly differed by gender. To do this, we fitted a multigroup model where all the parameters were estimated separately for males and females and tested whether constraining the factor loadings to be equal across groups significantly worsened the model fit. We did this separately for each model of psychopathology (i.e., correlated factors model and bifactor model) and did not observe a significant difference across models ( p values >.074), indicating that the factor structure did not differ between males and females.

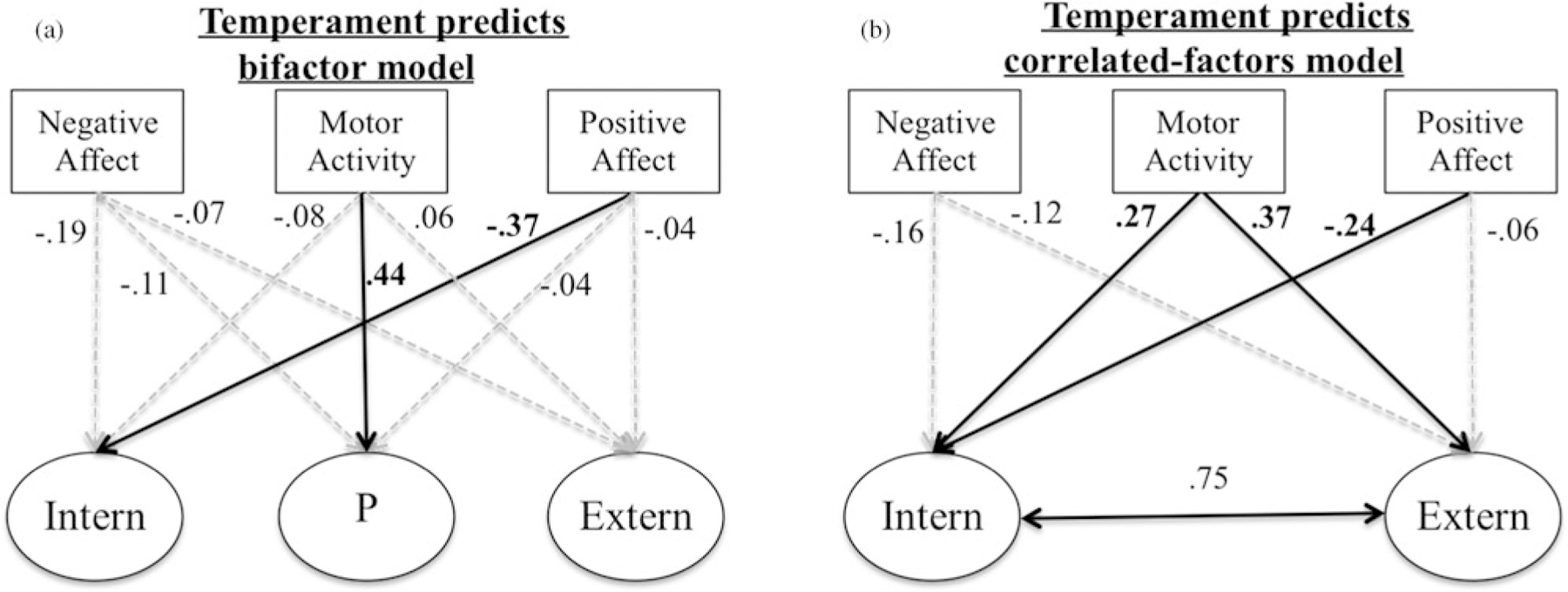

The impact of infant temperament on the bifactor model

In order to examine the relations between the temperament dimensions and psychopathology, we added the three temperament dimensions (motor activity, positive affect, and negative affect) as predictors of the three psychopathology factors (general psychopathology, internalizing, and externalizing) within the bifactor model. Moreover, we also included child gender, maternal ethnicity, and maternal education as covariates. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1a, motor activity levels significantly predicted the general psychopathology factor (β = .44, p < .001), such that increased motor activity levels in infancy predicted increased general psychopathology in childhood. Infant positive affect also significantly predicted the internalizing-specific factor (β = −.37, p = .009), such that increased positive affect in infancy predicted lower scores in the internalizing-specific factor. Importantly, these relations survived multiple comparison correction. No other relations between infant temperament and the latent psychopathology factors were statistically significant (Table 1 and Figure 1a). When examining for a potential moderation by gender in these relations, a chi-square difference test revealed a nonsignificant difference (Δχ2 (9) = 13.83, p = .129), indicating the relations between temperament and psychopathology factors did not significantly differ between males and females.

Table 1.

Regression paths from the path model of temperament composites predicting psychopathology factors

| Bifactor model |

Correlated factors model |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor/predictor | β | b | SE | z | p | LL | UL | β | b | SE | z | p | LL | UL |

| p factor | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Negative affect | −0.11 | −0.13 | 0.11 | −1.11 | 0.269 | −0.35 | 0.10 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Positive affect | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.12 | −0.43 | 0.667 | −0.30 | 0.19 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Motor activity | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 4.80 | 0.000 | 0.31 | 0.74 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Maternal ethnicity | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.76 | 0.447 | −0.24 | 0.54 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Maternal education | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.13 | −0.45 | 0.654 | −0.31 | 0.19 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Gender | −0.36 | −0.43 | 0.18 | −2.35 | 0.019 | −0.79 | −0.07 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Externalizing factor | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Negative affect | −0.07 | −0.08 | 0.15 | −0.53 | 0.596 | −0.37 | 0.22 | −0.12 | −0.18 | 0.11 | −1.56 | 0.119 | −0.40 | 0.05 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Positive affect | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.15 | −0.28 | 0.777 | −0.33 | 0.25 | −0.06 | −0.09 | 0.12 | −0.72 | 0.469 | −0.32 | 0.15 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Motor activity | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.694 | −0.26 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.10 | 5.17 | 0.000 | 0.32 | 0.70 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Maternal ethnicity | −0.16 | −0.18 | 0.25 | −0.72 | 0.470 | −0.66 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.43 | 0.668 | −0.31 | 0.48 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Maternal education | −0.20 | −0.22 | 0.16 | −1.43 | 0.152 | −0.53 | 0.08 | −0.09 | −0.14 | 0.12 | −1.22 | 0.224 | −0.38 | 0.09 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Gender | −0.22 | −0.24 | 0.24 | −1.02 | 0.309 | −0.71 | 0.23 | −0.21 | −0.47 | 0.17 | −2.79 | 0.005 | −0.79 | −0.14 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Internalizing factor | ||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Negative affect | −0.19 | −0.26 | 0.17 | −1.52 | 0.128 | −0.60 | 0.08 | −0.16 | −0.25 | 0.14 | −1.83 | 0.067 | −0.52 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Positive affect | −0.37 | −0.51 | 0.19 | −2.63 | 0.009 | −0.88 | −0.13 | −0.24 | −0.35 | 0.15 | −2.40 | 0.016 | −0.64 | −0.07 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Motor activity | −0.08 | −0.11 | 0.18 | −0.61 | 0.540 | −0.46 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 3.09 | 0.002 | 0.13 | 0.60 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Maternal ethnicity | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.31 | −0.20 | 0.842 | −0.67 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.39 | 0.697 | −0.34 | 0.51 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Maternal education | −0.37 | −0.50 | 0.19 | −2.65 | 0.008 | −0.87 | −0.13 | −0.23 | −0.35 | 0.14 | −2.40 | 0.016 | −0.63 | −0.06 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Gender | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.31 | 1.77 | 0.077 | −0.06 | 1.16 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.92 | 0.355 | −0.19 | 0.54 |

Note: p factor = general psychopathology factor, β = standardized estimates, b = unstandardized estimates, LL = lower limit of 95% confidence interval, UL = upper limit of 95% confidence interval. Bold estimates and p values showed statistical significance with adjustment for multiple comparisons (q < .05; FDR). Albeit the analysis with the bifactor model was performed following the methods recommended by Koch et al. (2018), the table is presented as a traditional regression analysis to simplify its presentation.

Figure 1.

Standardized regression coefficients for the regression models for temperament dimensions predicting latent psychopathology factor scores in the bifactor model (a) and the correlated factors model (b), along with parent-reported predicting latent psychopathology factor scores in the bifactor model (c) and the correlated factors model (d). Black solid arrows indicate statistically significant relations after correction for multiple comparisons (false discovery rate; FDR). Gray dotted arrows represent nonsignificant regression paths. Albeit the analysis with the bifactor model was performed following the recommended methods from Koch et al. (2018), the data are presented as traditional regression analyses to simplify the presentation. The effects of the covariates are not displayed in the figure, but are shown in Table 1.

The effects of infant temperament on the correlated factors model

In order to examine the relations between the temperament dimensions and the more traditional factors of psychopathology, we added the three temperament dimensions (motor activity, positive affect, and negative affect) as predictors of the psychopathology factors (internalizing and externalizing) within the correlated factors model. We also included child gender, maternal ethnicity, and maternal education as covariates. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 1b, motor activity levels significantly predicted the externalizing and internalizing factors (β = .37, p < .001 and β = .27, p = .002, respectively), such that increased motor activity levels in infancy predicted increased externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in childhood. Moreover, positive affect negatively predicted internalizing problems (β = −.24, p = .016). Importantly, these relations with activity levels and positive affect survived multiple comparison correction. No other relations between infant temperament and the latent psychopathology factors were statistically significant (Table 1 and Figure 1b).

In exploratory analyses examining the potential moderation by gender in these relations, the results revealed a significant difference (Δχ2 (6) = 20.76, p = .002), indicating that some of the relations between temperament and general psychopathology factors significantly differed between males and females. However, follow-up analyses comparing each regression path between males and females indicated that none of the paths significantly differed on their own – albeit several were marginally significant. Given the lack of a priori gender-specific hypotheses and absence of robust gender differences – particularly in the bifactor model, which is the focus of the current study – we did not explore gender differences further.

Discussion

The current study examined, for the first time, the specificity of longitudinal relations from infant temperament to general psychopathology and specific internalizing/externalizing psychopathology factors in childhood. This was achieved by examining whether a composite of observed and parent-reported motor activity and affective (positive and negative) characteristics in infancy predicted latent dimensions of psychopathology in mid and late childhood. The results converged across models of psychopathology to suggest that infant motor activity serves as a transdiagnostic risk factor, which longitudinally predicts a general psychopathology factor measured 7–12 years later. In addition, we found that low levels of positive affect in infancy predicted the internalizing-specific factor. This study is the first to examine individual differences in temperamental reactivity – comprehensively measured at 4 months of age – as transdiagnostic risk factors for psychopathology. The results have implications for the early identification of children at risk for a general liability for psychopathology.

Although some temperamental qualities in childhood have been related to latent dimensions of psychopathology in some studies, most have been concurrent, few have examined observed temperament, and not one has tested prospective relations from infancy to general psychopathology during mid to late childhood using a multimethod approach. In support of our hypotheses, we found that observed and parent-reported motor activity at age 4 months was a significant longitudinal predictor of the general psychopathology factor. This finding converges with a previous report showing associations between general psychopathology and parent-reported surgency – a temperament dimension for which activity level is an important indicator (Olino et al., 2014). Importantly, in the current study, we found that this effect was specific to motor activity levels and not to positive affect by examining these temperament dimensions separately, as opposed to examining a combined temperament factor that includes several temperament dimensions (e.g., surgency).

Even though most of the previously documented relations between motor activity and behavioral problems involve the externalizing domain, including hyperactivity and attention problems (De Pauw et al., 2009; Fagot & O’Brien, 1994; Miller et al., 2019; Schaughency & Fagot, 1993), these studies did not measure the shared variance among all behavioral problems. Moreover, other studies have found that activity level is related to other general outcomes such as overall behavioral problems (De Pauw et al., 2009), poor school adjustment (Jewsuwan, Luster, & Kostelnik, 1993; Zajdeman & Minnes, 1991), and increased conflict with parents and peers (Laible, Panfile, & Makariev, 2008). Similarly, studies have reported early surgency predicts both externalizing and internalizing problems (Stifter et al., 2008). In line with these studies, when examining the correlated factors model, we found that motor activity was predictive of both externalizing and internalizing problems. Importantly, these results replicated in the sensitivity analyses that separated the contributions of observed and parent-reported temperament, suggesting that these findings were not driven by common-method variance (see Tables S1 and S2 and Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material).

Theoretically, early motor activity may act as an expressional component of all emotions, regardless of emotional valence (Strelau & Zawadzki, 2012). As such, motor activity, especially in response to novelty, may reflect overall arousal rather than a particular emotional valence such as negative or positive affect. In line with this, infant motor activity is not predictive of specific diagnoses or psychopathology dimension (i.e., internalizing or externalizing), rather it is longitudinally predictive of psychopathology across diagnoses and dimensions. One possible mediator of this effect is self-regulation. Previous studies examining older children and adults suggest that general psychopathology is associated with lower executive functions as well as reports of effortful control (Hankin et al., 2017; Huang-Pollock et al., 2017; Martel et al., 2017; Olino et al., 2014). Similarly, early motor activity levels have been related to impulsivity and low levels of self-regulation (e.g., effortful control) (Abe, 2005; Buss, Block, & Block, 1980; Putnam & Rothbart, 2006; Shephard et al., 2019). As such, future studies should examine the role of self-regulation in childhood on the developmental pathways from early activity levels to general psychopathology along with testing the specificity of these potential differences by accounting for comorbidity in psychopathology.

In addition to the findings with motor activity, we found that low levels of positive affect predicted higher levels of internalizing. This was evident across both models of psychopathology (correlated factors and bifactor models). This finding is in line with previous studies that suggest that low levels of positive affect are associated with higher risk for internalizing problems (Durbin, Klein, Hayden, Buckley, & Moerk, 2005; Hankin et al., 2017; Olino et al., 2014; Watson, Gamez, & Simms, 2005). However, to our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to show this relation longitudinally from early infancy to later childhood. Contrary to our other predictions, we failed to find other significant relations between other temperament dimensions and general, externalizing, or internalizing psychopathology. Previous studies examining the relations between temperament and general psychopathology have mostly relied on parent reports for both temperament and psychopathology and have only evaluated concurrent associations (Hankin et al., 2017; Olino et al., 2014), increasing shared-method variance. Given that we examined the prospective relations of infant temperament from such a young age (4 months), it is possible that other processes, intrinsic and extrinsic to the child, moderate the effects of early temperament across childhood.

Our results also highlight the benefit of examining fine-grained dimensions based on scales or aspects of temperament rather than broad higher-order domains. Higher-order domains combine multiple aspects that, albeit related to each other, may have different relations to psychopathology. For example, surgency as a higher-order domain often combines several aspects, including activity level and positive affect. In the current study, only activity level was a significant predictor of general psychopathology. Positive affect, in addition to not being significantly related to general psychopathology, had effects that were consistently in the opposite direction to those of motor activity – this was most evident in the correlated factors model for internalizing. Similar effects have been found with children when differentiating positive affect and approach behaviors (Buss et al., 2014) as well as with adults distinguishing among communal extraversion and agentic extraversion (Watson et al., 2019). Together, these findings suggest that a broader temperament of factors like surgency (or extraversion) may mask the effects of fine-grained temperament dimensions like motor activity. As such, future studies should continue to examine subcomponents or aspects of temperament to provide a more comprehensive perspective of the relations between early temperament and its relation to later psychopathology.

We did not observe robust gender differences. We examined measurement invariance for the measurement model, finding evidence for factorial invariance across gender. This is in line with other studies that did not find gender differences in the structure of psychopathology (Huang-Pollock et al., 2017; Lahey et al., 2018) or studies including only one gender (Lahey et al., 2015). As expected, we found some gender differences in the mean levels of the psychopathology latent factors. However, we did not find significant gender differences in the longitudinal relations from early temperament to later psychopathology in the bifactor model or the correlated factors model. This is contrary to previous studies that have found gender differences in the relations between temperament and psychopathology (Miller et al., 2019; Morales et al., 2015, 2019; Rubin et al., 2003). However, to our knowledge, none of the previous temperament studies examined specific psychopathology factors modeled simultaneously or while accounting for the general psychopathology factor. Given the significant gender differences in the incidence of psychopathology, future studies should continue to explore potential gender differences in the developmental pathways from early temperament to specific psychopathology factors.

In line with an emerging literature of transdiagnostic risk (Caspi & Moffitt, 2018; Kotov et al., 2017), the results of the current study revealed that the general psychopathology factor was a better representation of the structure of psychopathology, capturing comorbidity across disorders. This result has important clinical implications as it implies that greater consideration should be taken in characterizing the origins of general psychopathology to help create transdiagnostic early indicators and interventions. The current study contributes to these efforts by expanding our knowledge of the etiology of general psychopathology and identifying an early individual-level characteristic, observed in the first months of life, to prospectively predict general psychopathology across childhood. This early characterization may help identify infants who are at the greatest risk for psychopathology later in life and could benefit the most from prevention efforts.

The current study has several strengths, including a prospective longitudinal design in a well-characterized cohort of children and a multimethod approach to assess infant temperament. Moreover, given recent concerns regarding the psychometric and conceptual properties of bifactor models (Burns, Geiser, Servera, Becker, & Beauchaine, 2020; Greene et al., 2019), we also estimated the correlated factors model, finding analogous longitudinal relations between infant temperament and psychopathology. However, our results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Our community sample comprised mostly well-educated non-Hispanic Caucasian families. Future research using larger and more diverse samples is needed to determine how other contextual variables contribute or interact with the longitudinal relations between early temperament and later psychopathology. Even with the limited range of maternal education in our sample, we observed that children of less educated mothers displayed higher levels of internalizing problems. Moreover, future work should examine these relations in clinical samples with higher rates and more varied forms of psychopathology. Finally, the fact that our sample was oversampled for high levels of infant temperamental reactivity should also be considered when generalizing the current findings to other populations. This sampling strategy might impact the findings since some of the relations may manifest differently in the context of high levels of infant temperamental reactivity. However, the sampling strategy likely also increased our power to detect the effects of temperament by providing us with a broader range of temperament variability in the sample.

Conclusion

Data from a longitudinal sample of children supported recent theoretical conceptualizations and empirical findings that suggest behavioral and emotional problems are organized with a general psychopathology dimension that captures overall levels of psychopathology, along with specific internalizing and externalizing dimensions. The current study also tested, for the first time, if infant temperament predicted later general and specific latent psychopathology dimensions. The results revealed that infant motor activity serves as an indicator of transdiagnostic risk that is longitudinally associated with general psychopathology, whereas low levels of positive affect in infancy predicted higher levels of the internalizing-specific factor. Clinically, better understanding of the links between early temperament and childhood psychopathology aids in both early identification and intervention efforts to support at-risk infants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the participating families, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Financial Statement.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (MH093349 and HD017899) to NAF.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material. The Supplementary Material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420001996

Conflicts of Interest. None.

References

- Abe JAA (2005). The predictive validity of the Five-Factor Model of personality with preschool age children: A nine year follow-up study. Journal of Research in Personality, 39, 423–442. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla L (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Allegrini AG, Cheesman R, Rimfeld K, Selzam S, Pingault J-B, Eley TC, & Plomin R (2020). The p factor: Genetic analyses support a general dimension of psychopathology in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61, 30–39. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, & Erkanli A (1999). Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 57–87. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bufferd SJ, Dougherty LR, Carlson GA, & Klein DN (2011). Parent-reported mental health in preschoolers: Findings using a diagnostic interview. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52, 359–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bufferd SJ, Dougherty LR, Carlson GA, Rose S, & Klein DN (2012). Psychiatric disorders in preschoolers: Continuity from ages 3 to 6. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 1157–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns GL, Geiser C, Servera M, Becker SP, & Beauchaine TP (2020). Promises and pitfalls of latent variable approaches to understanding psychopathology: Reply to Burke and Johnston, Eid, Junghänel and Colleagues, and Willoughby. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48, 917–922. doi: 10.1007/s10802-020-00656-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM, Block JH, & Block J (1980). Preschool activity level: Personality correlates and developmental implications. Child Development, 51, 401–408. [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Kiel EJ, Morales S, & Robinson E (2014). Toddler inhibitory control, bold response to novelty, and positive affect predict externalizing symptoms in kindergarten: Inhibitory control, positive affect, and externalizing. Social Development, 23, 232–249. doi: 10.1111/sode.12058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Spieker S, Burchinal M, Poe MD, & NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2006). Trajectories of aggression from toddlerhood to age 9 predict academic and social functioning through age 12. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Goldman-Mellor SJ, Harrington H, Israel S, … Poulton R (2014). The p factor: One general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 119–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, & Moffitt TE (2018). All for one and one for all: Mental disorders in one dimension. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 831–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, … Fox NA (2009). Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Class QA, Van Hulle CA, Rathouz PJ, Applegate B, Zald DH, & Lahey BB (2019). Socioemotional dispositions of children and adolescents predict general and specific second-order factors of psychopathology in early adulthood: A 12-year prospective study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128, 574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Hane AA, Henderson HA, Moas OL, Reeb-Sutherland BC, & Fox NA (2011). Longitudinal stability of temperamental exuberance and social–emotional outcomes in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 47, 765–780. doi: 10.1037/a0021316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw SS, Mervielde I, & Van Leeuwen KG (2009). How are traits related to problem behavior in preschoolers? Similarities and contrasts between temperament and personality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 309–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty LR, Klein DN, Durbin CE, Hayden EP, & Olino TM (2010). Temperamental positive and negative emotionality and children’s depressive symptoms: A longitudinal prospective study from age three to age ten. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29, 462–488. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.4.462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin CE, Klein DN, Hayden EP, Buckley ME, & Moerk KC (2005). Temperamental emotionality in preschoolers and parental mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 28–37. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, & Angold A (2006). Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 313–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, Losoya SH (2009). Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology, 45, 988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C, & Bandalos D (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8, 430–457. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot BI, & O’Brien M (1994). Activity level in young children: Cross-age stability, situational influences, correlates with temperament, and the perception of problem behaviors. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 40, 378–398. [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Calkins SD, & Schmidt LA (2001). Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Development, 72, 1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AL, & Eaton NR (2017). The temporal stability of the bifactor model of comorbidity: An examination of moderated continuity pathways. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 72, 74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AL, Eaton NR, Li K, Forbes MK, Krueger RF, Markon KE, …Docherty AR (2019). Are fit indices used to test psychopathology structure biased? A simulation study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128, 740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotzinger AD, Cheung AK, Patterson MW, Harden KP, & Tucker-Drob EM (2019). Genetic and environmental links between general factors of psychopathology and cognitive ability in early childhood. Clinical Psychological Science, 7, 430–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hane AA, Fox NA, Henderson HA, & Marshall PJ (2008). Behavioral reactivity and approach-withdrawal bias in infancy. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1491. doi: 10.1037/a0012855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Davis EP, Snyder H, Young JF, Glynn LM, & Sandman CA (2017). Temperament factors and dimensional, latent bifactor models of child psychopathology: Transdiagnostic and specific associations in two youth samples. Psychiatry Research, 252, 139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP, Engelhardt LE, Mann FD, Patterson MW, Grotzinger AD, Savicki SL, … Tucker-Drob EM (2020). Genetic associations between executive functions and a general factor of psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59, 749–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang-Pollock C, Shapiro Z, Galloway-Long H, & Weigard A (2017). Is poor working memory a transdiagnostic risk factor for psychopathology? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 1477–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewsuwan R, Luster T, & Kostelnik M (1993). The relation between parents’ perceptions of temperament and children’s adjustment to preschool. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 8, 33–51. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(05)80097-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PB (2013). Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202, s5–s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, & Fox NA (2006). Biology, culture, and temperamental biases. In Damon W & Lerner RM (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 167–225). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, & Snidman N (1991). Infant predictors of inhibited and uninhibited profiles. Psychological Science, 2, 40–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1991.tb00094.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, & Ustun TB (2007). Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20, 359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch T, Holtmann J, Bohn J, & Eid M (2018). Explaining general and specific factors in longitudinal, multimethod, and bifactor models: Some caveats and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 23, 505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Bagby RM, … Clark LA (2017). The hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126, 454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Keenan K, Stepp SD, Loeber R, & Hipwell AE (2015). Criterion validity of the general factor of psychopathology in a prospective study of girls. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 415–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Zald DH, Perkins SF, Villalta-Gil V, Werts KB, Van Hulle CA, … Poore HE (2018). Measuring the hierarchical general factor model of psychopathology in young adults. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 27(1), e1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laible D, Panfile T, & Makariev D (2008). The quality and frequency of mother–toddler conflict: Links with attachment and temperament. Child Development, 79, 426–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Pan PM, Hoffmann MS, Gadelha A, do Rosário MC, Mari JJ, … Bressan RA (2017). A general psychopathology factor (P factor) in children: Structural model analysis and external validation through familial risk and child global executive function. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126, 137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy E, Belsky J, Carragher N, Fearon P, & Patalay P (2018). Developmental stability of general and specific factors of psychopathology from early childhood to adolescence: Dynamic mutualism or p-differentiation? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59, 667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NV, Degnan KA, Hane AA, Fox NA, & Chronis-Tuscano A (2019). Infant temperament reactivity and early maternal caregiving: Independent and interactive links to later childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60, 43–53. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, Beekman C, Blandon AY, Stifter CA, & Buss KA (2015). Longitudinal associations between temperament and socioemotional outcomes in young children: The moderating role of RSA and gender. Developmental Psychobiology, 57, 105–119. doi: 10.1002/dev.21267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, Miller NV, Troller-Renfree SV, White LK, Degnan KA, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2019). Attention bias to reward predicts behavioral problems and moderates early risk to externalizing and attention problems. Development and Psychopathology, 1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0954579419000166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Murray AL, Eisner M, & Ribeaud D (2016). The development of the general factor of psychopathology ‘p factor’ through childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 1573–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Bufferd SJ, Dougherty LR, Dyson MW, Carlson GA, & Klein DN (2018). The development of latent dimensions of psychopathology across early childhood: Stability of dimensions and moderators of change. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 1373–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Dougherty LR, Bufferd SJ, Carlson GA, & Klein DN (2014). Testing models of psychopathology in preschool-aged children using a structured interview-based assessment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 1201–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penela EC, Walker OL, Degnan KA, Fox NA, & Henderson HA (2015). Early behavioral inhibition and emotion regulation: Pathways toward social competence in middle childhood. Child Development, 86, 1227–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, & Rothbart MK (2006). Development of short and very short forms of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 87, 102–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK (1981). Measurement of temperament in infancy. Child Development, 52, 569–578. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, & Fisher P (2001). Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The children’s behavior questionnaire. Child Development, 72, 1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, & Bates JE (2006). Temperament. In Damon W, & Lerner RM (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 99–166). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, Dwyer KM, & Hastings PD (2003). Predicting preschoolers’ externalizing behaviors from toddler temperament, conflict, and maternal negativity. Developmental Psychology, 39, 164–176. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, & Bentler PM (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66, 507–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaughency EA, & Fagot BI (1993). The prediction of adjustment at age 7 from activity level at age 5. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21, 29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedat S, Scott KM, Angermeyer MC, Berglund P, Bromet EJ, Brugha TS, … Kessler RC (2009). Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the world health organization world mental health surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 785–795. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzam S, Coleman JRI, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, & Plomin R (2018). A polygenic p factor for major psychiatric disorders. Translational Psychiatry, 8, 1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0217-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shephard E, Bedford R, Milosavljevic B, Gliga T, Jones EJ, Pickles A, … Baron-Cohen S (2019). Early developmental pathways to childhood symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60, 963–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HR, Hankin BL, Sandman CA, Head K, & Davis EP (2017). Distinct patterns of reduced prefrontal and limbic gray matter volume in childhood general and internalizing psychopathology. Clinical Psychological Science, 5, 1001–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HR, Young JF, & Hankin BL (2017). Strong homotypic continuity in common psychopathology-, internalizing-, and externalizing-specific factors over time in adolescents. Clinical Psychological Science, 5, 98–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CA, Putnam S, & Jahromi L (2008). Exuberant and inhibited toddlers: Stability of temperament and risk for problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 401–421. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strelau J, & Zawadzki B (2012). Activity as a temperament trait. In Zenter M & Shiner RL (Eds.), Handbook of temperament (pp. 83–104). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Troller-Renfree SV, Buzzell GA, Pine DS, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2019). Consequences of not planning ahead: Reduced proactive control moderates longitudinal relations between behavioral inhibition and anxiety. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58, 768–775.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Ellickson-Larew S, Stanton K, Levin-Aspenson HF, Khoo S, Stasik-O’Brien SM, & Clark LA (2019). Aspects of extraversion and their associations with psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128, 777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Gamez W, & Simms LJ (2005). Basic dimensions of temperament and their relation to anxiety and depression: A symptom-based perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 39, 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan KH, & Bentler PM (2000). Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data. Sociological Methodology, 30, 165–200. [Google Scholar]

- Zajdeman HS, & Minnes PM (1991). Predictors of children’s adjustment to day-care. Early Child Development and Care, 74, 11–28. doi: 10.1080/0300443910740102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.