Abstract

There is a paucity of robust clinical evidence for the role of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in patients with resectable non–small cell lung cancer. The primary aim of the study was to identify the available data on the feasibility, safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant immunotherapy. A systematic review was conducted using electronic databases. Relevant studies were identified according to predefined selection criteria. Five relevant publications on 4 completed trials were identified. In most studies, >90% of patients were able to undergo surgery within the planned timeframe after neoadjuvant immunotherapy. There was a high incidence of open thoracotomy procedures, either planned or converted from a planned minimally invasive approach. Mortality ranged from 0 to 5%, but none of the reported deaths were considered directly treatment-related. Morbidities were reported according to adverse events related to neoadjuvant systemic therapy, and postoperative surgical complications. Survival outcomes were limited due to short follow-up periods. Major pathologic response ranged from 40.5 to 56.7%, whilst complete pathologic response of the primary tumor ranged from 15 to 33%. Radiological responses were reported according to RECIST criteria and fluorodeoxyglucose-avidity. This systematic review reported safe perioperative outcomes of patients who underwent resection following neoadjuvant immunotherapy. However, there was a relatively high incidence of open thoracotomy procedures, partly due to the technical challenges associated with increased fibrosis and inflammation of tissue, as well as the more advanced stages of disease in patients enrolled in the studies. Future studies should focus on identifying predictors of pathological response.

Keywords: Neoadjuvant immunotherapy, Non—small cell lung cancer, Induction immunotherapy, Systematic review, Lung resection

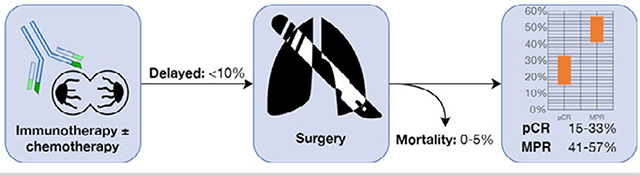

Graphical Abstract

Pathological response of primary lesion after neoadjuvant immunotherapy and surgery

INTRODUCTION

In the past decade, immunotherapy has revolutionized the treatment of patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1 As a group, these agents block inhibitory signals on the cancer cell’s surface, thereby facilitating the recognition of tumor antigens by autologous T-cell lymphocytes and subsequent destruction of tumor cells. The first developed agent in clinical use was ipilimumab, an IgG1 monoclonal antibody that blocks cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, inducing T cell cytotoxicity after exposure to tumor antigens.2 Other agents target the transmembrane programmed death 1 protein on the T-cell surface, or their ligand (PD-L1), on the tumor cell surface, enhancing antitumor immunity. Examples include nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and sintilimab, which inhibit programmed death 1 protein, and atezolizumab and durvalumab, which target PD-L1.3,4

In patients with untreated, advanced NSCLC, pembrolizumab was shown to be associated with superior overall survival, progress-free survival (PFS), and overall response rate compared to conventional platinum doublet systemic therapy in the KEYNOTE-024 trial.5 More recently, first-line treatment with combinational immunotherapy involving ipilimumab and nivolumab achieved superior overall survival compared to chemotherapy, independent of PD-L1 expression level, as demonstrated by the Checkmate 227 trial.6 Both of these trials were multicenter randomized prospective trials that evaluated the efficacy of immunotherapy as first-line treatment in stage IV patients. For patients with unresectable Stage III NSCLC without progression after concurrent chemoradiation, adjuvant durvalumab has demonstrated superior progress-free survival, with 3-year overall survival of 57.0% vs 43.5% compared to placebo in the PACIFIC trial.7,8 The outcomes of these trials have transformed the landscape of systemic therapy for metastatic and nonresectable advanced NSCLC, and immunotherapy has become the standard of care for selected patients.9

Encouraging results of immunotherapy in advanced NSCLC cohorts have posed new questions for its utility as neoadjuvant agents in patients with resectable NSCLC. Despite growing enthusiasm and a heightened interest within the thoracic surgical community, there is a relative paucity of robust clinical data. With the widespread adoption of immunotherapy in clinical practice, there is an urgent need to critically analyze the existing evidence in the neoadjuvant setting. The primary aim of the present systematic review was to identify the available data on the feasibility, safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in patients with resectable NSCLC.

METHODS

Literature Search Strategy

An electronic search was performed using Ovid Medline, EMBASE classic, EMBASE and all EBM Reviews from their dates of inception to July 2020. To identify all potentially relevant studies, we combined the search terms (“NSCLC” or “carcinoma, non-small cell lung” or “Non small cell lung”) and neoadjuvant* and (“surg*” or “resect*” or “lobectomy” or “VATS” or “thoracic surgery, video-assisted”) as either Medical Subject Headings or keywords. The reference lists of the retrieved articles were reviewed for further identification of potentially relevant studies. All identified articles were systematically assessed by applying the predefined selection criteria.

Selection Criteria and Data Extraction

Eligible studies for the present systematic review included those in which patients with histologically proven NSCLC were treated with immunotherapy prior to planned surgical resection and reported data on perioperative mortality and morbidity. All publications were limited to human subjects and in English language. Abstracts, conference presentations, editorials, expert opinions, and case studies involving fewer than 10 patients were excluded. All data were extracted from article texts, tables, figures, and supplementary files. Two investigators (AG and CC) independently reviewed each retrieved article. Discrepancies between the 2 reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus. The final results were reviewed by the senior investigators (CC and AC). Missing data from identified studies were obtained from the primary authors where possible.

RESULTS

Quantity and Quality of Trials

A total of 3635 references were identified through the electronic database searches. After exclusion of duplicated references, 2557 potentially relevant articles were retrieved for more detailed evaluation. After applying the selection criteria, 11 studies remained for assessment. Full articles were obtained and further evaluated, and 4 observational studies presented in 5 publications were included for quantitative analysis, as presented in the PRISMA chart in Figure 1.10–14 The first report by Yang et al was a single-arm phase II study including 13 patients who were treated with neoadjuvant ipilimumab and chemotherapy prior to surgical resection.10 The second report was a multi-institutional phase I trial that included 20 patients who underwent resection after neoadjuvant nivolumab. This study was initially reported by Forde et al with a focus on pathologic and radiologic response,11 followed by a subsequent publication by Bott et al emphasizing on the surgical technical details and postoperative outcomes.12 Gao et al reported a single-center phase I study involving neoadjuvant sintilimab.13 Shu et al presented a multi-center phase II trial on patients treated with neoadjuvant atezolizumab with paclitaxel and carboplatin.14 A summary of study characteristics is presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRIMSA flow chart detailing the literature search process for studies on neoadjuvant immunotherapy and surgery for non–small cell lung cancer.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics of Trials on Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy for Patients With Resectable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

| Study | Institutions | Recruitment Period | Follow-up (Months) | Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy | Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Yang,10 2018 | Duke University Medical Center | Mar 2013 to Dec 2015 | 24 | Ipilimumab 10 mg/kg, single dose Day 1 of neoadjuvant cycles 2, 3 | Paclitaxel, 175 mg/m2 with: - Cisplatin, 75mg/m2, or, - Carboplatin, AUC = 6 (max 900 mg) 3 cycles |

| Forde,11 2019 Bott,12 2019 |

John Hopkins Hospital MSKCC |

Aug 2015 to Oct 2016 | 20 | Nivolumab 3 mg/kg, single dose 4 and 2 weeks before surgery | - |

| Gao,13 2020 | PUMC | Mar 2018 to Mar 2019 | 3 | Sintilimab 200 mg 2 cycles q3w; 4 to 6 weeks before surgery | - |

| Shu,14 2020 | Columbia University, MGH, Dana Farber Cancer Institute | May 2016 to Mar 2019 | 13 | Atezolizumab 1200 mg, Day 1 of 3-week cycle, 4 cycles before surgery | Nab-paclitaxel, 100 mg/m2 on days 1,8, 15 of 21-day cycle Carboplatin, AUC = 5 (5 mg/mL per min) on day 1 of 21-day cycle 4 cycles |

AUC, area under curve; F/U, follow-up; MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre; PUMC, Peking Union Medical College.

Patient Selection and Feasibility

Yang et al enrolled 24 patients with cII-III NSCLC who were treated with ipilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and either cisplatin or carboplatin. After completion of induction therapy, 11 patients were excluded from an operation due to persistent N2 disease (n = 5), cancer progression (n = 2), inadequate pulmonary function (n = 2), location of tumor (n = 1), or preoperative complications (n = 1). Two patients had delayed surgery due to Ipilimumab-related diarrhea.10 Bott et al enrolled 22 patients with cI-III who were treated with 2 cycles of neoadjuvant nivolumab, at 4 and 2 weeks before resection.12 One patient was excluded due to histological diagnosis of small-cell lung cancer, and another patient experienced pneumonia after 1 dose of nivolumab and underwent uncomplicated resection at that time. Overall, 20 patients (91%) underwent resection after a median interval of 18 days from the second dose of neoadjuvant immunotherapy. Gao et al enrolled 40 patients, all of whom completed 2 cycles of sintilimab. Two patients’ operations were delayed beyond 6 weeks due to treatment-related adverse events.13 Shu et al enrolled 30 patients, one of whom was replaced after diagnosis of primary colorectal cancer, and another patient was excluded after developing brain metastasis prior to surgery.14 A summary of baseline patient characteristics, including clinical staging and histopathological type, is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline Patient Characteristics of Patients Treated With Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy and Surgical Resection for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

| Histopathology |

Clinical Stage |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Patients Enrolled | Patients Operated (n, %) | Surgical Delay (n) | Male | Age | Smoking History | SCC | ADC | Other | 1A | 1B | 2A | 2B | 3A | 3B |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Yang10 | 24 | 13(54%) | 2 | 38.5% | 59 (51 –75) | 92.3% | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 0 |

| Forde11 Bott12 | 22 | 20 (91%) | 0 | 47.6% | 67 (55–84) | 85.7% | 5 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 0 |

| Gao13,* | 40 | 40 (100%) | 2 | 82.5% | 62 (47–70) | 80.0% | 33 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 13 | 10 | 8 |

| Shu14 | 30 | 29 (97%) | 0 | 50.0% | 67 (62–74) | 100% | 12 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 23 | 0 |

ADC, adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Reported AJCC 8th edition staging system, all others reported 7th edition.

Surgical Approach and Resection Type

In Yang’s report, 1 patient underwent planned open thoracotomy and 12 were intended to undergo video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), but 3 out of these 12 procedures (25%) were converted to thoracotomy.10 Of the 20 patients who underwent resection by Bott et al, 13 cases were intended for a VATS or robotic-VATS approach, but 7 (54%) were converted to thoracotomy. Reports by Gao et al and Shu et al did not report their conversion rates, but open thoracotomy was performed in 74% and 54% of described cases, respectively. These findings demonstrated a relatively high proportion of patients who underwent open thoracotomy procedures and conversion to thoracotomies, when compared to patients with advanced-staged NSCLC who did not have neoadjuvant therapy.15,16 Lobectomies were the most common type of resection performed in all studies, followed by pneumonectomies, bilobectomies, wedge resections, and sleeve resections. Gao et al reported a relatively high proportion of patients (13/40, 33%) who underwent pneumonectomies when compared to 16% reported in the National Cancer Database for patients with Stage IIIA NSCLC.17 At the time of operation, Bott identified a patient to have tracheal invasion on preoperative bronchoscopy, and complete resection could not be performed.12 Gao reported 3 patients who underwent exploratory surgery without resection due to advanced disease, and Shu also reported 3 patients who had surgical exploration without resection.13,14 A summary of operative details is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

A Summary of Operative Details for Patients Who Underwent Surgery After Treatment With Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy for Non-small Cell Lung Cancer

| Type of Surgery (n) |

Surgical Approach (n) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Pneumonectomy | Bilobectomy | Lobectomy | Sleeve Lobectomy | Wedge Resection | Exploratory | Thoracotomy | MIS | Conversion to Thoracotomy |

|

| |||||||||

| Yang10 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 1 | - | 4 | 9 | 3 |

| Forde11 Bott12 | 2 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 1 | - | 14 | 6 | 7 |

| Gao13 | 13 | 5 | 18 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 29 | 10 | NR |

| Shu14 | 3 | 4 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 14 | 12 | NR |

MIS, minimally invasive surgery; NR, not reported.

Mortality and Morbidity

Gao et al reported 2 postoperative mortalities (5%) resulting from disturbance of consciousness 8 days after the operation, and immune-mediated pneumonia 1 month after the operation, both of which were reported to be unrelated to treatment.13 Shu et al reported 1 mortality (3.4%) due to pneumonia and respiratory failure, which was also considered not to be related to treatment.14 Bott et al and Yang et al did not report any mortalities. These outcomes were comparable with large, contemporary series of patients who underwent surgical resection for advanced-staged NSCLC without neoadjuvant immunotherapy, which have reported 30-day mortality ranging from 2 to 3%.15,18 Perioperative morbidities were divided according to treatment related adverse effects due to neoadjuvant therapy and postoperative complications related to surgery. The most common postoperative complications included prolonged air leak, atrial arrhythmias, urinary tract infections, and need for blood transfusions, as summarized in Table 4. Grade 3–4 major complications included pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, vasodilatory shock, and atrial arrhythmia. When reported, the median length of hospitalization was 4–5 days.10,12,14 A summary of adverse outcomes resulting from neoadjuvant therapy is presented in Supplementary Table 1, with Grade 3–5 major adverse events summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 4.

A Summary of Postoperative Complications for Patients Who Underwent Surgery After Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

| Study | 30-Day Mortality | Pneumonia | Atrial Arrhythmia | Urinary Complications | Blood Transfusion | Air Leak | PE | ACS | Pain | Pyrexia | Seizure | Shock | Wound Infection | Others | LOS (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Yang10 | 0 | 0 | 1^ | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1† | - | 1 | 5 (4–6) |

| Forde11 Bott12 | 0 | 1* | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 4(2–17) |

| Gao13 | 2 | 1† | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1* | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Shu14 | 1 | 1† | 3 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 (3–6) |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; LOS, length of stay; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Grade 3–4 adverse event.

Grade 5 adverse event.

Overall Survival and Disease-Free Survival

Yang et al reported a median overall survival of 29.2 months, with 24-month overall survival of 73.0% for all 24 patients who were enrolled into the study.10 Forde et al reported that the duration of recurrence-free survival had not been reached at the time of data analysis, and the rate of recurrence-free survival at 18 months was 73%.11 Shu et al reported a median disease-free survival of 17.9 months, whilst overall survival was not reached.14 Gao et al only provided a median follow-up of 3.2 months without any survival data.13

Pathological Response

The median pathological response reported by 3 studies was 50–92.5%.11,13,14 Major pathological response, defined as 10% or less of residual viable tumor cells in the resected primary tumor, was reported to be 40.5–56.7%.11,13,14 Complete response, defined as no viable tumor within the resected specimen, was reported to be 15–33.3% for the primary lesion and 8.1–10% for both the primary lesion as well as the lymph nodes, when specified.10,11,13,14 A summary of these outcomes are presented in Figure 2, along with a Graphical Abstract presented in Figure 3. Pre-treatment PD-L1 expression from biopsy samples were obtained in the majority of patients in 3 studies,11,13,14 but only Gao et al reported a correlation between PD-L1 expression in stromal cells at the primary site at baseline and the percentage of pathologic response. Notably, they found no correlation in PD-L1 expression between baseline biopsy and surgical samples for either stromal cells or tumor cells.13

Figure 2.

Pathological response of primary lesion after neoadjuvant immunotherapy and surgery.

Figure 3.

Summary of systematic review of neoadjuvant immunotherapy before surgical resection for patients with resectable non–small cell lung cancer.

Radiological Response

Three studies utilized the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST, version 1.1) to evaluate radiographic response after neoadjuvant therapy prior to surgery.11,13,14 None of the patients in any of the studies achieved complete response, and 10–60% of patients achieved partial response, as summarized in Table 5. Only Shu et al reported a significant association between major pathological response and RECIST criteria response categories (P= 0.0022).14 Maximal standardized uptake value (SUVmax) on positron emission tomography (PET) was found to be associated with major pathological response by Gao et al, with a reduction of 62.8% from baseline in major pathological responders compared to 2.5% in nonresponders (P< 0.00001).13 Forde et al described a poor correlation between radiologic and pathologic response, with 2 patients who achieved complete pathologic response found to have stable disease according to RECIST. The phenomenon of ‘pseudo-progression’ was emphasized by the authors, and may misrepresent the response of tumors to immunotherapy according to CT and PET scans traditionally utilized to re-stage patients after induction therapy.11 A video demonstration of the fibrotic and inflammatory changes to the hilar lymph nodes encountered during a robotic-assisted right upper lobectomy after neoadjuvant immunotherapy is presented in in Video 1.

Table 5.

A Summary of Pathological and Radiological Response of Patients Treated With Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

| Study | Pathological Response |

Radiological Response* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Pathological Response | Major Response | Complete Response Primary Lesion | Complete Response Primary Lesion + Lymph Nodes | CR | PR | SD | PD | |

|

| ||||||||

| Yang9 | NR | NR | 2/13(15.4%) | NR | 0 | 14/24(58.3%) | 2/24 (8.3%) | 8/24 (33.3%) |

| Forde10 Bott11 | 65% | 9/20 (45.0%) | 3/20 (15.0%) | 2/20 (10%) | 0 | 2/21 (9.5%) | 18/21 (85.7%) | 1/21 (4.8%) |

| Gao12 | 50% | 15/37(40.5%) | 6/37 (16.2%) | 3/37 (8.1%) | 0 | 8/40 (20.0%) | 28/40 (70.0%) | 4/40 (10.0%) |

| Shu13 | 92.5% | 17/30 (56.7%) | 10/30 (33.3%) | NR | 0 | 19/30(63.3%) | 9/30 (30.0%) | 2/30 (6.7%) |

CR, complete response; NR, not reported; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

According to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria.

DISCUSSION

Immunotherapy has proven to be the most promising new alternative treatment modality in the management of lung cancer in recent years, with at least 230 registered trials currently recruiting patients (www.clinicaltrials.gov). A number of possible advantages of neoadjuvant immunotherapy have been proven or hypothesized, including its systemic priming of antitumor T cells in micrometastases, its improvement in compliance with systemic therapy, and an unique opportunity to study the in vivo effects of antitumor immunity in the primary lesion and peripheral blood.11,19,20 The present systematic review aimed to critically analyze the existing clinical data on the utility of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in the treatment of resectable NSCLC.

Key findings of the systematic review include the feasibility and safety of prescribing immunotherapy prior to surgical resection without significant delays. Apart from the initial pilot study by Yang et al, which had a relatively high proportion of patients with stage III disease (77%), all identified studies reported that more than 90% of enrolled patients underwent surgery within the planned timeframe. Causes for delay to surgery were most often related to treatment-related adverse events such as diarrhea, hypothyroidism, and elevated liver enzymes.10,13 For patients who underwent surgery, exploratory procedures without lung resection were reported by Gao et al (7.5%) and Shu et al (10.3%), respectively. An interesting finding was the relatively large proportion of patients who underwent thoracotomy (31–74%), and there was a considerable proportion of patients who underwent conversion from an intended minimally invasive approach to an open procedure (25–54%), reflecting the technical challenges associated with the pseudoprogression phenomenon that includes an infiltration of lymphocytes, macrophages, tumor death-cholesterol clefts, neovascularization and proliferative fibrosis.11,12 Predictors of these phenomena were not clearly related to pathological response to immunotherapy.12 Postoperative mortality was reported by Gao et al (5%) and Shu et al (3.4%), but none of the deaths were considered to be treatment-related.13,14 Regarding adverse events, the most common complications related to neoadjuvant immunotherapy included skin rash, hepatitis, diarrhea, and thyroid dysfunction, whilst neoadjuvant chemotherapy reported hematological disorders, alopecia, fatigue, and peripheral neuropathy. Additionally, common postoperative complications included prolonged air leak, atrial arrhythmia, urinary tract complications, pneumonia, and need for blood transfusions.10,12–14 Significant pathological response was reported in 3 studies that provided routine analysis of surgical specimens,12–14 but predictors of pathologic response were inconsistent between studies, with PD-L1 expression being predictive in some studies13 but not others.11,14 Similarly, pathologic response identified from surgical specimens do not appear to be consistently related to radiographic response identified by CT or PET imaging after neoadjuvant therapy.12–14

Limitations of the present systematic review include the relative paucity of identified studies in the existing literature, and potential publication bias needs to be acknowledged. However, with the rapid growth in the number of active trials on neoadjuvant immunotherapy, there is an urgent need to provide an overview of the available data to date. The follow-up periods of the identified studies were also relatively short, with limited data on disease-free survival and overall survival outcomes. Predictors of pathological response remain elusive, and correlation to radiological response is inconsistent. With maturing data in the current trials, surgeons will be able to refine preoperative investigations and be better informed about potential operative and treatment-related complications to optimize clinical outcomes within a multi-disciplinary setting. Thoracic surgeons should continue to play a proactive role in identifying predictors of pathologic response and refining the role of checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of NSCLC.

PATIENT CONSENT

waived due to the nature of the study as a Systematic Review.

Supplementary Material

Central Message.

The present systematic review summarizes the existing clinical evidence on neoadjuvant immunotherapy for resectable non–small cell lung cancer.

Perspective Statement.

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for non–small cell lung cancer can be prescribed with an acceptable safety profile.

Complete pathologic response was reported in 15–33% of primary tumors.

Major pathologic response was reported in 40.5–56.7% of primary tumors.

Open thoracotomy, either planned or as a result of conversion, was relatively high.

Predictors of pathological response remain inconsistent between studies.

Acknowledgments

Dr Annabelle Mahar for her expert advice on pathological data.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Abbreviations:

- NSCLC

non—small cell lung cancer

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4

- PD-1

programmed death 1 protein

- PD-L1

programmed death 1 protein ligand

- PFS

progression free survival

- VATS

video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

- N

nivolumab

- NI

nivolumab plus ipilimumab

Footnotes

Disclosures: Professor Franca Melfi was an official proctor for Intuitive Surgical. Dr. Zielinski was on the Advisory Board for BMS, Pfizer, and received Speaker Honorarium from BMS, Astra Zeneca, MSD.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Scanning this QR code will take you to the article title page to access supplementary information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Mulshine JL, et al. : Lung cancer: Current therapies and new targeted treatments. Lancet 389:299–311, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch TJ, Bondarenko I, Luft A, et al. : Ipilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment in stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol 30:2046–2054, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchbinder EI, Desai A: CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways: Similarities, differences, and implications of their inhibition. Am J Clin Oncol 39:98–106, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi Y, Su H, Song Y, et al. : Safety and activity of sintilimab in patients with relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (ORIENT-1): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 6:e12–e19, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. : Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 375:1823–1833, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. : Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 381:2020–2031, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. : Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 377:1919–1929, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray JE, Villegas AE, Daniel DB, et al. : Three-year overall survival update from the PACIFIC trial. J Clin Oncol 37:8526., 2019.−8526 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K, et al. : Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 30:863–870, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang CJ, McSherry F, Mayne NR, et al. : Surgical outcomes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and ipilimumab for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 105:924–929, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forde PM, Chaft JE, Smith KN, et al. : Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med 378:1976–1986, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bott MJ, Yang SC, Park BJ, et al. : Initial results of pulmonary resection after neoadjuvant nivolumab in patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 158:269–276, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao S, Li N, Gao S, et al. : Neoadjuvant PD-1 inhibitor (Sintilimab) in NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 15:816–826, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shu CA, Gainor JF, Awad MM, et al. : Neoadjuvant atezolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with resectable non-small-cell lung cancer: An open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 21:786–795, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boffa D, Fernandez FG, Kim S, et al. : Surgically managed clinical stage IIIA-clinical N2 lung cancer in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. Ann Thorac Surg 104:395–403, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao C, Cerfolio RJ, Louie BE, et al. : Incidence, management, and outcomes of intraoperative catastrophes during robotic pulmonary resection. Ann Thorac Surg 108:1498–1504, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hancock J, Rosen J, Moreno A, et al. : Management of clinical stage IIIA primary lung cancers in the National Cancer Database. Ann Thorac Surg 98:424–432, 2014. discussion 432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang-Lazdunski L: Surgery for nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur Respir Rev 22:382–404, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cottrell TR, Thompson ED, Forde PM, et al. : Pathologic features of response to neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 in resected non-small-cell lung carcinoma: A proposal for quantitative immune-related pathologic response criteria (irPRC). Ann Oncol 29:1853–1860, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandt WS, Yan W, Zhou J, et al. : Outcomes after neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy for cT2–4N0–1 non-small cell lung cancer: A propensity-matched analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 157:743–753.e743, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.