Abstract

Objective

Explore children’s and adolescents’ (CADs’) lived experiences of healthcare professionals (HCPs).

Design

Scoping review methodology provided a six-step framework to, first, identify and organise existing evidence. Interpretive phenomenology provided methodological principles for, second, an interpretive synthesis of the life worlds of CADs receiving healthcare, as represented by verbatim accounts of their experiences.

Data sources

Five key databases (Ovid Medline, Embase, Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus, and Web of Science), from inception through to January 2019, reference lists, and opportunistically identified publications.

Eligibility criteria

Research articles containing direct first-person quotations by CADs (aged 0–18 years inclusive) describing how they experienced HCPs.

Data extraction and synthesis

Tabulation of study characteristics, contextual information, and verbatim extraction of all ‘relevant’ (as defined above) direct quotations. Analysis of basic scope of the evidence base. The research team worked reflexively and collaboratively to interpret the qualitative data and construct a synthesis of children’s experiences. To consolidate and elaborate the interpretation, we held two focus groups with inpatient CADs in a children’s hospital.

Results

669 quotations from 99 studies described CADs’ experiences of HCPs. Favourable experiences were of forming trusting relationships and being involved in healthcare discussions and decisions; less favourable experiences were of not relating to or being unable to trust HCPs and/or being excluded from conversations about them. HCPs fostered trusting relationships by being personable, wise, sincere and relatable. HCPs made CADs feel involved by including them in conversations, explaining medical information, and listening to CADs’ wider needs and preferences.

Conclusion

These findings strengthen the case for making CADs partners in healthcare despite their youth. We propose that a criterion for high-quality child-centred healthcare should be that HCPs communicate in ways that engender trust and involvement.

Keywords: paediatrics, quality in health care, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our findings have advanced current evidence by providing a comprehensive overview of children’s and adolescents' (CADs') experiences of healthcare professionals, while providing a blueprint for the child-centred care conceptual model.

In addition to completing a scoping review in line with a published protocol, this article reports an interpretive phenomenological synthesis of the evidence base.

Restricting included articles to the English language limited the scope of our review.

Limitations in the metadata provided by primary researchers prevented subgroup analyses.

The subjectivity of interpretive synthesis is both a limitation and a strength: a limitation, because it does not meet quantitative, experimental standards of proof; and a strength because we used our subject position as clinicians to help fellow clinicians earn the trust of CADs.

Background

Children’s experiences, like patients’ experiences in general, are of fundamental importance in healthcare.1–3 Research consistently shows that favourable experiences are associated with a wide range of positive health outcomes, including adherence to recommended treatments, uptake of preventive care, and utilisation of healthcare resources.3 Exploring, understanding and adapting to patients’ experiences, particularly those concerning interpersonal communication, is the hallmark of patient-centred care (PCC), which is what patients ‘strongly want’.4 5 Accordingly, PCC has become the dominant ideology in healthcare design and delivery.6

In the case of children, however, it has proven more difficult to establish a model of PCC. Children and adolescents (CADs) are distinct from adults; they are developing physically, intellectually and emotionally, and they occupy different positions in society and by law.7 CADs, therefore, typically experience healthcare as part of a family unit, accompanied by parents or guardians who often act on their behalf. These factors affect the roles that CADs occupy within healthcare settings—how they interact and communicate with others—and predispose them to asymmetric relationships with adults. To address this, two specific theoretical models of care—family-centred care (FCC) and child-centred care (CCC)—have been developed for use in paediatric practice, based on the principles of PCC but incorporating modified conceptualisations of centredness.8

In FCC, the family is the central unit of care, with the aspiration of an equal partnership between healthcare professionals (HCPs) and families. FCC, which first originated in the 1950s, was an important conceptual advance because, up to this point, no framework existed to involve parents in their children’s care.7 Recent research shows, however, that even within the FCC framework, parents and professionals tend to predominate and CADs struggle to be true participants.9 In contrast, the newer concept of CCC situates CADs at the centre of healthcare practice, giving primacy to their voices and experiences. Rather than being guided by outsider perspectives of children’s best interests, CCC compels HCPs to consciously perceive and understand children’s conditions, experiences and priorities, as viewed through their eyes8 10 11:

[CCC] requires providers to critically consider the child’s perspective in every situation while ensuring collaboration with the family who the [child] is part of.8

While aspects of FCC and CCC may be pertinent in different clinical contexts,12 experts now advocate a move towards CCC,13 arguing that it better upholds values laid down by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and governing bodies (such as the General Medical Council),14 15 and could improve how CADs experience healthcare.8 13

Adopting the CCC approach, however, requires a major shift in thinking and practice. Research suggests that HCPs’ realities are incompatible with CADs’, with HCPs focused on prioritising tasks, ‘getting the job done’, and mitigating, rather than engaging with, CADs’ demands.16 Furthermore, HCPs’ communication strategies adopted for consulting CADs are largely underpinned and conceptualised by biomedical or psychosocial models, from the clinical gaze,17 with little or no input from CADs.18 19 And while CADs’ healthcare experiences overall are generally positive, large-scale studies have identified shortcomings in how HCPs interact and communicate,20–22 impacting on CADs’ ability to manage their conditions and participate in decision-making.23 HCPs, too, continue to find communicating with CADs challenging, supporting a change in thinking and practice.19

To achieve the vision of CCC, then, HCPs need greater insight into the experiences of sick children.11 This reflects a wider drive towards co-production (providers and service users working in equal partnership to effect change) in children’s healthcare;24 25 and also complements the present impetus to acknowledge and examine CADs’ own experiences, opinions, and priorities, within research,26 27 quality improvement,28–30 and standard setting.31 To date, however, most research and surveys examining experiences in paediatric settings have relied on parents’ accounts, while CADs have participated less, if at all.32 Nevertheless, the few studies that have explored CADs’ own experiential accounts have found them to be informative and distinct from parents’.23 33 At present, these accounts are widely dispersed, yet if compiled, synthesised, and interpreted, these could provide a rich account of CADs’ lived experiences of how they encounter HCPs.

This study aimed to explore how CADs experience HCPs within interpersonal interactions, in order to provide practitioners, organisations, and policy-makers with evidence that could promote child-centred communication. First, we conducted a scoping literature review to systematically gather evidence on CADs’ experiences of HCPs. Second, we interpreted CADs’ extracted quotations from the perspective of phenomenology. This well-established methodological tradition, grounded in philosophy, enables researchers to produce valid interpretations by examining and interpreting participants’ verbatim accounts of their lived experience.34 Finally, we organised the interpretation into a synthetic account of how CADs experience their interactions with HCPs.

Methods

Methodological orientation

Scoping review methodology has a pragmatic orientation in the sense that it sets out to map existing published evidence on a topic but it is adaptable in the sense that the usefulness of its procedures is not tied to any one specific epistemology (theory of the nature of knowledge).35–37 As in our previously published research,38 this review augments scoping review procedures with interpretive phenomenology. The latter has an ontology (theory of the nature of being) derived from the philosophy of Husserl, according to which the lived experience of research participants is a legitimate topic of qualitative inquiry. Interpretive phenomenology helps researchers respond reflexively to spoken or written words and arrive at valid, subjective interpretations. Phenomenologists typically take a reflexive stance that consciously sets aside strong a priori preconceptions while allowing their own experiences (such as, in our case, having experience of caring for sick children) to help them construct an informative interpretation.34 The quality of a constructivist interpretation is to be judged by its trustworthiness, authenticity and ability to catalyse action—which, in this case, would be to improve future children’s healthcare experiences.39

Study procedures

The research followed a published protocol (accessible at https://rdcu.be/b2FFk),40 which proposed to supplement traditional scoping review procedures with an interpretive synthesis, the distinction between which is explained in the previous paragraph. The scoping component followed the 6-step framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley,35 Levac et al,36 and Colquhoun et al,37 adhering to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews reporting guidance (included in online supplemental file 1).41

bmjopen-2021-054368supp001.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

Step 1: defining the research question

This was: ‘What is known about children’s and adolescents’ experiences of healthcare professionals, from their present perspective?’, the final phrase emphasising our commitment to CADs’ contemporaneous accounts of their experiences expressed in their own words, rather than parents’ descriptions or adults describing childhood memories.

Step 2: identifying relevant articles

We used the STARLITE mnemonic (sampling strategy, type of study, approaches, range of years, limits, inclusion and exclusions, terms used, electronic sources) and designed a search strategy (summarised in table 1) to identify all published articles containing CADs’ experiences of HCPs expressed as first-person direct quotations.42 A subject librarian constructed a database search (included in online supplemental file 2), using the population, context and concept framework,43 combining the terms ‘children’ or ‘adolescents’, ‘healthcare’, and ‘experience’ (and synonyms), limiting it to English language articles, ‘qualitative research’, and ‘0 to 18 years’, and then running it on Ovid Medline, Embase, Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus and Web of Science from inception to 11 January 2019. We included other articles found by searching relevant reference lists or found opportunistically.

Table 1.

STARLITE summary of search strategy42

| Sampling strategy | Comprehensive: attempting to identify all published materials |

| Types of studies | Any published study contributing to the research question: qualitative (with or without other methodologies (ie, mixed method)); primary or secondary sources |

| Approaches | Electronic database searching; manual searching of reference lists; articles found opportunistically |

| Range of years | From database inception until 11 January 2019 |

| Limits | Articles published in English language; ‘qualitative research’; children aged 0–18 years (inclusive) |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | See table 2 and step 3: study selection |

| Terms used | See online supplemental file 2 |

| Electronic databases | Ovid Medline; Embase; Scopus; CINAHL Plus; Web of Science |

CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

bmjopen-2021-054368supp002.pdf (42KB, pdf)

Step 3: study selection

Refinement of selection criteria

As is customary in scoping review, the process iterated between searching, selecting, extracting data and refining the research question. To enhance the rigour of this process, and in keeping with our interpretive stance, we responded reflexively to the accumulating evidence, discussing our interpretations, and articulating a clear rationale for each refinement. All records were imported to Mendeley Reference Manager, duplicates removed, titles and abstracts screened against five screening questions (box 1), and full texts of those that screened positive reviewed against eligibility criteria.

Box 1. Screening questions.

Are the participants children and adolescents (CADs; <18 years)?

Is the study examining an aspect of health, illness, or healthcare?

Are CADs participating as recipients of healthcare?

Are participants aged >18 years excluded from the study?

Do children or adolescents describe experiences?

These criteria, at first provisional (table 2A), were progressively refined in response to the heterogeneity of evidence. Table 2B shows final criteria. GD led the process of first-screening, annotating, sorting and collating articles. MK and TD supported her by second screening 10% of records, discussing results, assessing articles whose eligibility was in doubt and responding to the often-imprecise details given by researchers. Any ambiguities (ie, lack of age ranges) during screening led to full-text review and a final decision about eligibility against criteria. To optimise validity of the selection process, GD rescreened all records and annotations after each refinement and, finally, after definitive criteria had been set.

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria for article selection

| A. Provisional | B. Definitive |

| Inclusion criteria: | |

|

|

| Exclusion criteria: | |

|

|

CADs, children and adolescents; HCP(s), healthcare professional(s).

Rationale for criteria

We included children up to and including 18 years because late adolescents are increasingly cared for in paediatric settings.44 45 Our age range conforms, also, with the United Nations’ influential definition of adolescence.46 We included articles that contained verbatim quotations irrespective of methodology. Judgement of methodological quality was not a criterion for three reasons: it is not standard practice in scoping reviews; it is notoriously difficult to judge qualitative research categorically47; and the interpretive synthesis used verbatim quotations, whose validity does not depend on what the primary researchers did with CADs’ words. Because authors often failed to report the exact age of patient participants they quoted, we excluded any study that included patient participants aged >18 years (see, eg, Tjaden et al48).

Step 4: Charting the data

GD and MK piloted a spreadsheet to chart study characteristics, contextual information, and all CADs’ verbatim quotations on 10 articles; this resulted in the final dataset shown in box 2, which GD then used to extract data on the remaining articles.

Box 2. Data extracted.

Study characteristics:

First author.

Year published.

Country of origin.

No. children and adolescents (CADs) participating.

Age range of CAD participants.

Male to female (or non-binary) ratio.

Other participants (eg, parents).

Methods.

Methodology (or analytical approach).

Contextual information:

Study focus (the experience being explored).

Health setting.

Health condition.

Length of healthcare encounter being explored.

CADs’ quotations:

All first-person direct quotations, where CADs are talking about HCPs.

Age and gender referenced to each quotation.

When key information was missing or unclear, we sought clarification from primary authors. All authors independently reviewed the extracted information for its fitness to address the aims and purpose of the study, subsequently conferring to optimise the validity of the dataset.

Step 5: collating, summarising, and reporting the results

We first analysed the basic characteristics of included studies. We then identified themes in the verbatim quotations following Braun and Clarke’s method of thematic analysis as defined by their checklist (included in online supplemental file 3).49 50 GD immersed herself in the data, reviewing all quotations on Microsoft Excel, using NVivo V.12 qualitative analysis software to support generation of codes and construction of themes.51 Other team members supported her interpretation, by reviewing quotations first individually, and then collectively. We systematically interrogated the data for themes that had meaning in relation to the research question, revising candidate themes periodically (with the aid of a visual thematic map) to ensure these were coherent, distinctive, complementary and relevant. The ensuing thematic structure had central concepts, which we used to organise subordinate themes and their associated codes. Throughout this process, we constantly compared our evolving interpretation against the original data, including a final ‘quality control’ check of the synthesis against all quotations.49 50

bmjopen-2021-054368supp003.pdf (58.2KB, pdf)

In keeping with our interpretive stance, we used our different subject positions as paediatricians, a family doctor and an adult internist to interpret CADs’ words reflexively and arrive at ‘beyond-surface insights’, so that the themes were amenable to an additional stage of phenomenological synthesis.34 50 As we did this, the gamut of emotional content in CADs’ words became an increasingly compelling influence on our interpretation. CADs’ emotional expressions tended to have quite distinct ‘valence’ (defined as the attractiveness (positive valence) or averseness (negative valence) of the emotions described) which linked in recurring ways to HCPs’ reported behaviours.52 53 So, for example, a HCP who related well to a child might engender trust, while an HCP who related poorly might engender mistrust.

While crude dichotomies between positive/negative emotions and behaviours do not reflect the subtlety of interpretive research, links between these contrasting behaviours were so clearly present that they offered a parsimonious way of presenting our results. The results section uses the terms ‘favourable’ and ‘unfavourable’ to specify what are, in reality, nuanced polarities. To epitomise these important themes in ways that could encourage HCPs to emulate favourable behaviours, we present predominantly favourable behaviours, but provide negative counter-examples to emphasise the breadth of CADs’ experiences. As in previous research,54 we used CADs’ own words, as far as possible, to construct a narrative of findings that was as true as possible to the phenomena experienced and narrated by children. We use the wording ‘HCPs did X’ as a shorthand for the more correct wording, ‘CADs experienced HCPs as doing X’.

Step 6: stakeholder consultations

As recommended by Levac et al,36 GD, AT and RC (with research ethics and governance approvals) recruited CADs aged 8–16 from inpatient wards in the Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children to two focus groups whose aim was to consolidate and elaborate on findings. Participants and parents chose whether parents should attend. We presented candidate themes along with exemplar quotations and facilitated discussions, asking participants to comment on provisional findings and provide suggestions for practice. We audio-recorded sessions and transcribed recordings verbatim. We reviewed transcripts alongside the provisional findings to authenticate, build on, and summarise a final narrative of results. Participants’ identities are pseudonymised in the results section.

Patient and public involvement

The essence of this research was to involve children, although as expressed verbatim by other researchers. The stakeholder consultation further fulfilled the patient and public involvement component of the research by ensuring findings disseminated were intelligible and relevant.

Results

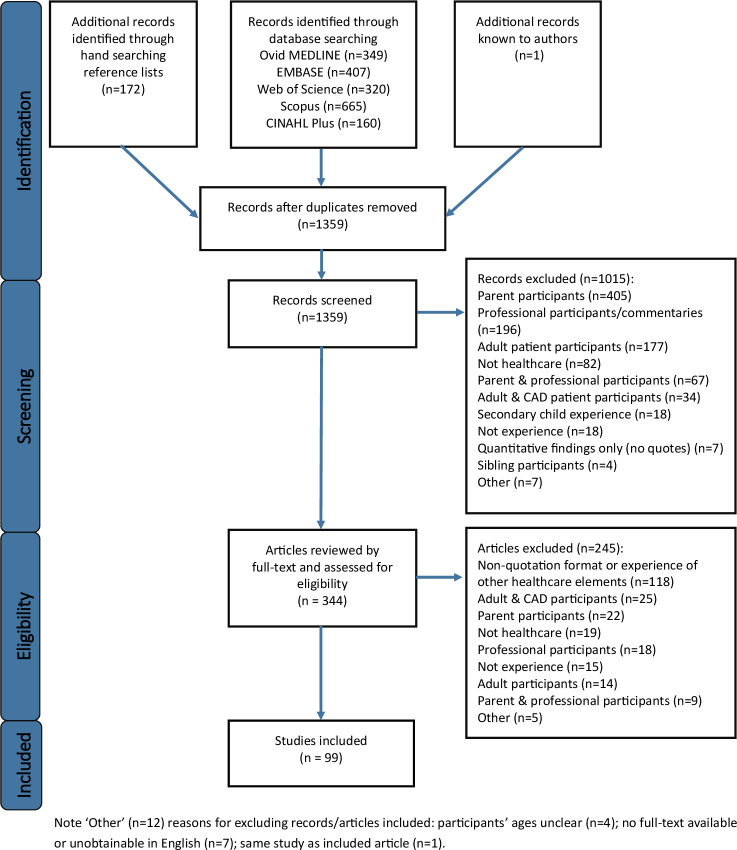

We identified 1359 articles, excluding 1015 by screening and 245 by reviewing full texts, and categorised reasons for exclusion on a PRISMA flow diagram (shown in figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. CAD, child and adolescent.

Overview of included studies

Table 3 presents an overview of included studies (n=99), published between 1992 and 2018. In total, 4448 CADs, aged 11 months to 18 years, participated. Most studies included 8–50 participants (n=73), aged 7 or older (n=70), and used interviews only (n=64). Studies commonly included CADs with chronic and potentially debilitating or life-threatening conditions (such as asthma and cancers), explored long-term experiences (over months to years), and focused on hospital care. Further descriptive findings and figures are presented in online supplemental file 4.

Table 3.

Study characteristics

| Study details | CAD participants | Design | Contextual information | Data | |||||||

| First author, year | Country | N | Age (years) | M:F | Methods | Methodology/analytical approach | Study focus (experience of) | Health setting | Health condition | Length of encounter | Quotes (n) |

| Aalsma et al61, 2014 | USA | 19 | 11–17 | 12:7 | INT | Qualitative | CAMHS | Non-specific | Mental health illness | Long term | 5 |

| Alex62, 1992 | Canada | 24 | 7–11 | 13:11 | INT, Q | Content analysis | Pain | Hospital | Surgical (post-op) | Short term | 4 |

| Anderson et al63, 2017 | England | 6 | 15–18 | 3:3 | INT | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | Lung transplantation | Hospital | Post-lung transplantation | Long term | 6 |

| Ångström-Brännström et al64, 2008 | Sweden | 7 | 4–10 | 3:4 | INT (PT) | Thematic analysis | Being comforted | Hospital | Chronic | Short term | 6 |

| Ångström-Brännstrom et al65, 2014 | Sweden | 9 | 3–9 | 5:4 | INT | Content analysis | Comfort during cancer treatment | Hospital | Cancer | Long term | 3 |

| Beresford et al66, 2003 | England | 63 | 11–16 | 27:36 | INT, FG (PT) | Framework method | Communicating | Hospital | Chronic | Long term | 14 |

| Boyd et al67, 1998 | Canada | 6 | 10–13 | 2:4 | INT (PT), WT | Grounded theory | Hospital and coping strategies | Hospital | Surgical (chronic) | Long term | 3 |

| Brown et al68, 2014 | USA | 19 | 11–17 | 12:7 | INT | Grounded theory | Therapeutic alliances | Hospital | Mental health illness | * | 16 |

| Carney et al69, 2003 | Scotland | 213 | 4–17 | 115:98 | INT, FTQ | Thematic analysis | Healthcare | Hospital | Non-specific | Non-specific | 9 |

| Cheng et al70, 2003 | Taiwan | 90 | 5–14 | 45:45 | INT | Content analysis | Pain | Hospital | Non-specific | Non-specific | 1 |

| Cheng et al71, 2016 | Taiwan | 11 | 12–18 | 7:4 | INT | Content analysis | Cancer recovery | Hospital | Cancer | Long term | 1 |

| Christofides et al72, 2016 | Canada | 19 | 8–18 | 7:12 | INT | Thematic analysis | Research participation | Hospital | Cystic fibrosis | Long term | 3 |

| Clift et al73, 2007 | Wales | 6 | 11–15 | 3:3 | INT | Qualitative | Emergency admission | Hospital | Non-specific | Short term | 7 |

| Colver et al74, 2018 | England | 374 | 14–18 | 219:155 | INT, Q, OBS | Constant comparison | Transition | Hospital | Medical | Long term | 2 |

| Corsano et al75, 2015 | Italy | 27 | 6–15 | 12:15 | INT | Qualitative | Emotional events | Hospital | Cancer/ blood disorders | Long term | 4 |

| Coyne et al76, 2006 | Ireland | 55 | 7–18 | 30:25 | INT, FG | Constant comparison analysis | Participating/decision-making | Hospital | Non-specific | Non-specific | 52 |

| Coyne77, 2006a | Ireland | 11 | 7–14 | * | INT | Grounded theory | Hospitalisation | Hospital | Non-specific | * | 1 |

| Coyne78, 2006b | Ireland | 11 | 9–14 | * | INT (PT), FTQ, OBS | Grounded theory | Participating | Hospital | Non-specific | * | 4 |

| Coyne et al79, 2007 | Ireland | 17 | 7–16 | * | INT | Qualitative | Hospitalisation | Hospital | Non-specific | Non-specific | 8 |

| Coyne et al80, 2011 | Ireland | 55 | 7–18 | 31:24 | INT, FG | Qualitative | Communicating/decision-making | Hospital | Non-specific | Non-specific | 20 |

| Coyne et al81, 2012 | Ireland | 38 | 7–18 | * | INT (PT) | Content analysis | Hospital and HCPs | Hospital | * | * | 24 |

| Coyne et al82, 2014 | Ireland | 20 | 7–16 | 11:9 | INT (PT) | Constant comparison analysis | Participating/decision-making | Hospital | Cancer | Long term | 2 |

| Coyne et al83, 2015 | Ireland | 15 | 12–18 | 6:9 | INT, FG | Thematic analysis | CAMHS | Non-specific | Mental health illness | Long term | 6 |

| Coyne et al55, 2016 | Ireland | 20 | 7–16 | 11:9 | INT | Grounded theory | Communicating | Hospital | Cancer | Long term | 6 |

| Curtis et al84, 2017 | England | 17 | 5–16 | * | INT (PT), OBS | Ethnographic | Single/ shared rooms | Hospital | * | * | 3 |

| Das et al85, 2017 | India | 14 | 8–15 | * | FG | Qualitative | Living with HIV | Non-specific | HIV | Long term | 1 |

| Day et al86, 2006 | England | 11 | 9–14 | 5:6 | FG | Thematic Analysis | CAMHS | Non-specific | Mental health illness | Long term | 13 |

| Dell’Api et al87, 2007 | Canada | 5 | 10–17 | 2:3 | INT | Qualitative | Interacting with HCPs | Hospital | Non-specific | Long term | 19 |

| Dixon-Woods88, 2002 | England | 20 | 8–16 | 9:11 | INT | Constant comparison analysis | Asthma services | Community | Asthma | Long term | 12 |

| Edgecombe et al89, 2010 | England | 22 | 11–18 | 16:6 | INT | Thematic analysis | Asthma services | Hospital | Asthma | Long term | 5 |

| Ekra et al90, 2012 | Norway | 9 | 7–12 | 5:4 | INT, OBS (PT) | Hermeneutic phenomenology | Hospitalisation | Hospital | TIDM | Long term | 2 |

| Engvall et al91, 2016 | Sweden | 13 | 5–15 | 6:7 | INT (PT) | Content Analysis | Radiotherapy | Hospital | Cancer | Long term | 2 |

| Forsner et al92, 2005 | Sweden | 7 | 7–10 | 4:3 | INT | Thematic analysis | Illness | Hospital | * | Short term | 4 |

| Forsner et al93, 2009 | Sweden | 9 | 7–11 | 2:7 | INT, OBS | Hermeneutic phenomenology | Fear | Hospital | Non-specific | Short term | 4 |

| Garth et al94, 2009 | Australia | 10 | 8–12 | 3:7 | INT | Grounded theory | Participating | Non-specific | Cerebral palsy | Long term | 3 |

| Gill et al95, 2016 | England | 12 | 14–17 | 2:10 | INT | Thematic analysis | CAMHS inpatient ward | Non-specific | Mental health illness | Long term | 2 |

| Griffiths et al96, 2011 | Australia | 9 | 8–16 | * | INT | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | Living with cancer | Non-specific | Cancer | Long term | 3 |

| Haase et al97, 1994 | USA | 7 | 5–18 | 3:4 | INT (PT) | Colaizzi’s method of phenomenological analysis | Completing cancer treatment | Non-specific | Cancer | Long term | 6 |

| Hall et al98, 2013 | England | 17 | 8–17 | * | INT | Thematic analysis | Life with repaired cleft lip/ palate | Non-specific | Cleft lip/ palate | Long term | 1 |

| Han et al99, 2011 | China | 29 | 7–14 | 16:13 | INT | Content analysis | Cancer | Hospital | Cancer | Long term | 2 |

| Hanson et al100, 2017 | USA | 30 | 4–14 | 16:14 | INT | Narrative analysis | Pain | Hospital | Fractured arm | Short term | 5 |

| Harper et al101, 2014 | England | 10 | 16–18 | 3:7 | INT | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | CAMHS | Non-specific | Mental health illness | Long term | 8 |

| Hart et al102, 2018 | England | 14 | 14–16 | * | INT | Thematic analysis | CAMHS | Non-specific | Mental health illness | Long term | 2 |

| Hawthorne et al103, 2011 | England | 21 | 7–16 | 12:9 | FG | Thematic analysis | Diabetes services | Hospital | T1DM | Long term | 8 |

| Hinton et al104, 2015 | England | 21 | 8–17 | 6:15 | INT (PT) | Constant comparison analysis | A multiple sclerosis diagnosis | Non-specific | Multiple sclerosis | Long term | 3 |

| Hodgins et al105, 1997 | Canada | 85 | 5–13 | 38:41 | INT, Q | Mixed method | Venepuncture | Hospital | Non-specific | Short term | 3 |

| Hutton106, 2005 | Australia | 7 | 13–18 | 3:4 | INT (PT) | Qualitative | Adolescent wards | Hospital | Cystic fibrosis/ asthma | Long term | 3 |

| Jachyra et al107‡, 2018a | Canada | 8 | 11–17 | 4:4 | INT | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | Talking about weight | Non-specific | ASD | Long term | 6 |

| Jachyra et al108‡, 2018b | Canada | 8 | 11–17 | 4:4 | INT | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | Talking about weight | Non-specific | ASD | Long term | 4 |

| Jensen et al109, 2012 | Denmark | 8 | 8–10 | 5:3 | INT (PT) | Thematic analysis | Acute hospitalisation | Hospital | Medical | Short term | 6 |

| Jongudomkarn et al110, 2006 | Thailand | 49 | 4–18 | 31:18 | INT, FG, OBS, PT | Content analysis | Pain | Non-specific | Non-specific | Long term | 1 |

| Kluthe et al111, 2018 | Canada | 18 | 6–17 | 11:7 | INT | Content analysis | IBD diagnosis | Hospital | IBD | Long term | 1 |

| Koller et al112, 2010 | Canada | 21 | 5–18 | 12:9 | INT (PT) | Grounded theory | Hospitalisation during SARS | Hospital | Non-specific | Long term | 2 |

| Koller113, 2017 | Canada | 26 | 5–18 | 11:15 | INT (PT) | Thematic analysis | Medical education/participating | Hospital | Chronic | Long term | 10 |

| Kortesluoma et al114‡, 2006 | Finland | 44 | 4–11 | * | INT | Content analysis | Pain | Hospital | Non-specific | Non-specific | 1 |

| Kortesluoma et al115‡, 2008 | Finland | 44 | 4–11 | 27:17 | INT | Content analysis | Pain | Hospital | Non-specific | Non-specific | 7 |

| Lewis et al56, 2007 | Australia | 9 | 8–16 | 5:4 | INT | Cognitive mapping | Receiving care | Hospital | * | * | 5 |

| Livesley et al16, 2013 | England | 15 | 5–15 | 3:2 | INT (PT), OBS | Critical ethnography, constant comparison analysis | Hospitalisation | Hospital | Surgical | Long term | 4 |

| Lowes et al23, 2015 | Wales | 518 | 7–15 | * | FTQ | Qualitative descriptive analysis | Life with T1DM and services | Hospital | T1DM | Long term | 8 |

| Macartney et al116, 2014 | Canada | 12 | 9–18 | 6:6 | INT | Content analysis | Life after a brain tumour | Non-specific | Brain tumour | Long term | 1 |

| Manookian et al117, 2014 | Iran | 6 | 6–17 | 3:3 | INT | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | Stem cell transplantation | Hospital | Cancer and blood disorders | Long term | 4 |

| Marcinowicz et al118, 2016 | Poland | 22 | 10–16 | 8:14 | INT | Content analysis | Nurse relationships and wards | Hospital | * | * | 7 |

| Marshman et al119, 2010 | England | 10 | 12–14 | 5:5 | INT, Q | Framework analysis | Malocclusion treatment | Non-specific | Malocclusion | Long term | 1 |

| McNelis et al120, 2007 | India | 11 | 7–15 | 6:5 | FG | Thematic analysis | Living with epilepsy | Non-specific | Epilepsy | Long term | 2 |

| McPherson et al121, 2017 | Canada | 17 | 6–18 | 8:9 | INT | Phenomenology, thematic analysis | Talking about weight | Hospital | Spina Bifida | Long term | 3 |

| McPherson et al122, 2018 | Canada | 18 | 10–17 | 9:9 | INT, FG | Thematic analysis | Talking about weight | Hospital | Non-specific | Long term | 3 |

| Moules123, 2009 | England | 138 | 9–14 | 82:56 | INT (PT) | Framework analysis | Hospital care | Hospital | * | * | 3 |

| Nguyen et al124, 2010 | Sweden | 40 | 7–12 | * | INT, Q, vital signs | Content analysis | Music therapy for lumbar puncture | Hospital | Cancer | Short term | 1 |

| Nilsson et al125, 2011 | Sweden | 39 | 5–10 | 32:7 | INT | Content analysis | Pain | Hospital | Skin trauma | Short term | 4 |

| Noreña Peña et al126‡, 2011 | Spain | 30 | 8–14 | 13:17 | INT, OBS | Critical incident technique | Communicating with nurses | Hospital | Surgical | * | 24 |

| Noreña Peña et al127‡, 2014 | Spain | 30 | 8–14 | 13:17 | INT, OBS | Critical incident technique | Communicating with nurses | Hospital | Surgical | * | 22 |

| Olausson et al128, 2006 | Sweden | 18 | 4–18 | 8:10 | INT | Hermeneutic phenomenology | Life after transplantation | Non-specific | Post- transplant | Long term | 6 |

| Pelander et al129, 2004 | Finland | 40 | 4–11 | 28:12 | INT | Content analysis | Nursing care | Hospital | Chronic (T1DM and other) | Long term | 3 |

| Pelander et al130, 2010 | Finland | 388 | 7–11 | 198:188† | FTQ | Content analysis | Hospitalisation | Hospital | Non-specific | Non-specific | 2 |

| Pölkki et al131, 1999 | Finland | 20 | 7–11 | * | INT, WT | Content analysis | Pain | Hospital | Non-specific | * | 1 |

| Pope et al132, 2018 | Australia | 15 | 4–8 | 11:4 | INT (PT) | Thematic analysis | Pain and nurses' roles | Hospital | Trauma | Short term | 1 |

| Randall133, 2012 | England | 21 | 0.9–17 | 8:12† | INT, FG (PT), PTD | Colaizzi’s method of phenomenological analysis | Community children’s nursing | Community | Non-specific | Long term | 4 |

| Rankin et al134, 2018 | Scotland | 24 | 9–12 | 13:11 | INT (PT) | Thematic analysis | Managing T1DM | Non-specific | T1DM | Long term | 1 |

| Roper et al27, 2018 | England | 16 | 7–15 | 9:7 | INT | Qualitative | Research participation/ consent | Hospital | Asthma or anaphylaxis | Short term | 7 |

| Ruhe et al135, 2016 | Switzerland | 17 | 9–17 | 11:6 | INT | Thematic analysis | Participating | Hospital | Cancer | Long term | 1 |

| Ryals136, 2011 | USA | 8 | 13–17 | 6:2 | INT | Phenomenology | Therapeutic relationships | Non-specific | Mental health illness | Long term | 59 |

| Saarikoski et al137, 2018 | Finland | 19 | 6–12 | 7:12 | FG | Content analysis | Therapeutic intervention | Community (school) | Enuresis | Long term | 1 |

| Salmela et al138, 2010 | Finland | 90 | 4–6 | * | INT | Colaizzi’s method of phenomenological analysis | Hospital related fears | Hospital | * | * | 4 |

| Schalkers et al139, 2014 | The Nether-lands | 63 | 6–18 | 31:32 | INT (PT), WT | Action research | Hospital care | Hospital | Non-specific | * | 8 |

| Schmidt et al140, 2007 | USA | 65 | 5–18 | 34:31 | INT, FTQ | Thematic analysis | Nurses in hospital | Hospital | Non-specific | Non-specific | 45 |

| Spalding et al141, 2016 | England | 7 | 8–14 | 2:5 | WS (PT) | Action research, thematic analysis | Good doctors | Hospice | Palliative | Long term | 3 |

| Stevens et al142, 2006 | Canada | 14 | 7–16 | 9:5 | INT | Content analysis | Home chemotherapy | Community (home) | Cancer | Long term | 1 |

| Taylor et al143, 2010 | England | 14 | 12–18 | * | INT | Framework analysis | Life after transplantation | Non-specific | Liver transplant | Long term | 6 |

| Vejzovic et al144, 2014 | Sweden | 17 | 10–17 | 5:12 | INT | Content analysis | Preparing for colonoscopy | Hospital | Suspected IBD | Short term | 4 |

| Vindrola-Padros145, 2012 | Argentina | 10 | 8–16 | 5:5 | INT (PT) | Narrative analysis | Living with cancer | Non-specific | Cancer | Long term | 4 |

| Wangmo et al146, 2016 | Switzerland | 17 | 9–17 | 11:6 | INT | Qualitative | Cancer services and treatment | Hospital | Cancer | Long term | 5 |

| Watson et al147, 2009 | USA | 9 | 14–18 | 7:1:1¶ | INT | Grounded theory | Accessing CAMHS & mental illness | Non-specific | Mental health illness | Long term | 1 |

| Wen et al148§, 2013 | Singapore | 203 | 4–18 | * | INT, OBS | Thematic analysis | Pain | Non-specific | Surgical (post-op) | Non-specific | 15 |

| Wise149, 2002 | USA | 9 | 7–15 | * | INT (PT) | Hermeneutic phenomenology | Transplantation | Non-specific | Liver transplant | Long term | 7 |

| Wong et al150, 2012 | China | 79 | 10–13 | 54:25 | FG | Qualitative | Weight-loss programme | Community (school) | Obesity | Long term | 1 |

| Woodgate151, 2008 | Canada | 13 | 9–17 | 7:6 | INT | Constant comparison analysis | Cancer symptoms | Non-specific | Cancer | Long term | 1 |

| Wray et al152, 2018 | England | 543 | 8–16 | * | INT, FG, Q | Framework Analysis | Healthcare | Hospital | * | * | 5 |

| Xie et al153, 2016 | China | 21 | 7–12 | 12:9 | INT | Content Analysis | Lumbar puncture | Hospital | ALL | Short term | 15 |

| Young et al154, 2003 | England | 13 | 8–17 | 8:5 | INT | Constant comparison analysis | Communicating | Hospital | Cancer | Long term | 7 |

Note: non-specific, not focusing on a certain type or area.

*Unable to ascertain.

†Numerical inconsistency detected in source article.

‡Same study with different quotations presented.

§Qualitative systematic review.

¶Non-binary gender.

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CAMHS, child and adolescent mental health service; FG, focus groups; FTQ, free-text questionnaires; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IDB, inflammatory bowel disease; INT, interviews; OBS, observations; PT, participatory techniques employed; PTD, photo talk diaries; Q, quantitative questionnaires; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; WS, workshops; WT, writings.

bmjopen-2021-054368supp004.pdf (539.7KB, pdf)

Children’s and adolescents’ experiences

Six-hundred and sixty-nine quotations referred to CADs’ experiences of HCPs, most of whom were doctors or nurses. CADs also spoke about their experiences with counsellors, psychologists, social workers and dentists. CADs’ ages (available for 397 quotations), ranged from 5 to 18 years (average 13); male and female participants were equally represented (see online supplemental file 5). All quotations extracted are available at https://doi/10.5061/dryad.t76hdr817; quotations presented below are cited in online supplemental file 6.

bmjopen-2021-054368supp005.pdf (50.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-054368supp006.pdf (77.2KB, pdf)

CADs’ favourable experiences were of HCPs forming trusting relationships and involving them in healthcare discussions and decisions and their unfavourable experiences were generally towards the opposite pole.

Forming trusting relationships

Their nature

Being in a trusting relationship was feeling a ‘bond’, having an ‘emotional attachment’, or having a ‘best friend’. CADs and HCPs knew each other, could ‘relate to’ each other, and really understood each other. There was openness, transparency, and there was trust. CADs trusted in HCPs to provide ‘good care’, knowing they would do everything necessary, and do it right.

Their origins

At first, HCPs were ‘strangers’; CADs did not know the HCPs, who they were, and how they were. HCPs, likewise, did not know CADs, their histories, or their personalities. Repeated contact and dialogue built and reinforced relationships: ‘As time passed, […] we created that bond.’

HCPs engendered trusting relationships by demonstrating positive attributes, including being able to empathise. CADs trusted in HCPs who were ‘very smart’, ‘experienced’, ‘[knew] what to do’, ‘[took] care’, and did ‘everything the best they [could]’. They trusted HCPs who were ‘truthful’, ‘100% with you’, and ‘just [told] you straight up.’ Such HCPs did ‘not tell children any lies’; ‘nothing [was] hidden’. CADs built trusting relationships with HCPs who were ‘really nice’, ‘nurturing, caring, and helpful people who [were] there for you’, and had a ‘good sense of [humour]’.

HCPs related to CADs by understanding them: ‘she knew what I was talking about, she knew what I was feeling, she knew how I was feeling.’ HCPs ‘took time to get to know’ CADs and had ‘real conversations, not just [HCP]-patient discussions’, in which they shared experiences and got to know each other personally. CADs could better relate to HCPs who were ‘down to earth’ and had ‘a lot in common’.

Their effects

Trust was vital: ‘you gotta have trust.’ Trusting relationships improved CADs’ healthcare experiences by promoting positive emotions. CADs felt ‘satisfied’ and ‘happy’. They enjoyed their time with HCPs and had ‘good memories’. CADs were more able to ‘open up’ or ‘tell anything’ to HCPs whom they trusted. Trusting relationships gave CADs hope that HCPs could ‘cure [the] illness’ or help lessen the pain. CADs who trusted HCPs submitted themselves more willingly to recommended treatments: ‘whatever happens I let them [HCPs] do what they have to do to help me get better.’ And they consciously chose to remain with or seek out HCPs they trusted. CADs admired trustworthy HCPs: ‘individually [they’re] all heroes.’ And they aspired to be like them: ‘Because you can save people […] I’m going to be a children’s doctor.’

Being involved in healthcare discussions and decisions

The nature of involvement

CADs who were fully involved in healthcare discussions felt they knew everything; ‘everything [was] always clear’ to them. They had a seat at the table to discuss issues that affected them and felt acknowledged as key stakeholders. CADs worked ‘together’ with HCPs and parents; they felt as though they were respected, taken ‘seriously’, and treated ‘as an equal’.

Its origins

HCPs involved CADs by including them in conversations, sharing information, providing opportunities to ask questions, taking time to answer, and listening to their wider needs and preferences. HCPs who promoted involvement used simple words, communicated in a timely way, gave accurate information at the right pace, and explained things so that CADs understood. These HCPs brought CADs ‘into all the conversations’ by talking to CADs ‘as much as they [talked to the] parents’. Parents facilitated CADs’ involvement in the presence of HCPs or afterwards by ‘[breaking] the words down in an easier explanation’. HCPs promoted participation by ‘listening’ to and respecting CADs’ requests: ‘I tell them I don’t want this and they … understand’. For more complex decisions, CADs took a joint approach: ‘me because I know my own body, my parents because they know what’s best for me […] and the paediatrician because they are qualified.’

Its effects

CADs viewed involvement as ‘most important, as in the end it is about [them]’. CADs enjoyed being involved; it was ‘brilliant’, and they looked forward to their next visit. CADs were more satisfied with healthcare; they found it ‘interesting and informational’. Getting to ‘learn something new’ made them feel ‘comfortable and confident’. CADs could ‘make better decisions’ because they were ‘fully informed’. This promoted self-advocacy and self-efficacy: ‘I’m asking the doctor more questions myself than having my Dad do it.’

Not forming trusting relationships or being involved

CADs described unfavourable experiences, which broadly mirrored favourable ones. For instance, trust was undermined by HCPs getting things wrong, being ‘nasty’, and not ‘[seeming] that concerned’. HCPs being unfamiliar to CADs because they were ‘too busy’ or because HCPs or CADs moved to other services prevented trusting relationships forming. HCPs excluded CADs by using ‘big words’, speaking too fast, or telling them nothing, so that CADs could not understand. HCPs neglecting to ask CADs or asking in a tokenistic way prevented them ‘having a say’: ‘they [HCPs] might ask me ‘is that ok’ […] in such a way that I kind of feel like I don’t have any other option but [to] agree with them’. HCPs and parents side-lined CADs by talking behind the curtains so CADs could not hear or sticking them ‘in the middle’ of a conversation where they could not interrupt. Some parents told CADs to keep quiet or dominated conversations: ‘you try to say something but then your parents just say shhhhh! […] They come out and say, […] did you understand that, you say no, they say, you should have asked them, and then you say, oh you didn’t let me, they say rubbish!’

Not trusting people or understanding what was happening made CADs fearful. HCPs who made CADs feel ‘rejected’ and objectified, ‘like a piece of machinery’, enraged them. CADs found it ‘hard to talk’, disengaged in conversations, and left the talking to their parents. Not trusting in HCPs or being uninvolved meant some CADs hated hospital or clinic, they objected to attending, and sought information or guidance from other sources.

Stakeholder consultations

Two CAD inpatients participated in each of two focus groups (3 females and 1 male, aged 11–15 years) lasting 67 and 93 min respectively. Their medical conditions included type 1 diabetes, coeliac disease, spina bifida, and spinal/brain surgery. No parents attended. Three authors (GD, AT, and RC) attended both consultations and a hospital play specialist attended the first consultation. Participants identified with the provisional findings and elaborated on them (table 4). All wanted some degree of involvement in their own care though the amount of information and level of participation they wanted depended on their age, what was being discussed, and individual preferences. Box 3 offers take-home messages for HCPs.

Table 4.

Stakeholder findings: focus group participants’ experiences mapped to overarching themes

| Overarching themes | Forming trusting relationships | Being involved in healthcare discussions and decisions |

| Favourable experiences | Rachel, a young girl with diabetes, described having a very good relationship with the diabetic team and ward staff: ‘Hm, it’s just the nurses really like nice. Like, the first night I was staying over they were staying it’s a sleepover and stuff.’ (Rachel, FG1, line 746 & 747) She acknowledged how continuity of care helped her become more familiar with the staff: ‘they’re always in the clinic when I am there’. (Rachel, FG1, line 678) She commented on how the diabetic team got to know her, by chatting casually and taking an interest in her wider life: ‘they like asked me what school I’m going to this year’ and about ‘my baby sister and stuff’. (Rachel, FG1, line 815–819) Participants experienced some HCPs as being easier to talk to than others. Rachel felt that she could talk to the diabetic team: ‘(…)I can talk to them more ‘cos you know them.’ (Rachel, FG1, line 621) From the perspective of Laura, a young girl with a recent diagnosis of diabetes, a caring nature was an important factor: ‘[HCPs who] make you feel as if they care [were easier to talk to]’. (Laura, FG2, line 432) |

Laura was well informed by her hospital consultant, who had seen her when she was first diagnosed with diabetes: ‘My consultant like came the day before(…)and he explained the whole thing in detail.’ (Laura, FG2, line) Laura’s experience of being well informed resembled Rachel’s: ‘The doctor like normally tells me everything that I need to know anyway and they put it in like ways that I like, know.’ (Rachel, FG1, line 657 & 658) Sarah, an adolescent with spina bifida and scoliosis, felt she had some control over her treatment: ‘Uhm, I might have to get the surgery on my back, because I’ve got scoliosis, em, so if it gets like really, it’s not too bad but if it gets worse I have to have surgery so I feel as if I have like a choice because I don’t have to have it, and I don’t want it.(…)I don’t want to have it.’ (Sarah, FG2, line 743–748) Although all participants wanted to be informed, the oldest participant, Darren, a young boy with spina bifida and epilepsy, preferred his parents to ask and answer questions, and doctors to make decisions on his behalf: ‘GD: Do you ever have any questions (Darren)? Darren: Ah…don't think so. AT: Are you happy for your parents to ask the questions? Darren: Yeah. AT: And you just listen? Darren: Yeah (smiling and laughing).’ (Verbatim excerpt, FG1, line 555–560) |

| Unfavourable experiences | Sarah found it difficult to trust HCPs who were uncaring: ‘Well yesterday I had to get a line [cannula] in and there was four different doctors that tried(…)and I thought like the doctors didn’t really care, they were just gonna get it in, they didn’t really care what I was thinking.(…)Well I know they needed to do it. But they didn’t care,(…)they didn’t care if they hurt me.’ (Sarah, FG2, line 438–441 & 512) | During her cannulation experience, Sarah felt angry because HCPs failed to grant her wishes: ‘I always tell them to put it, try my feet first because I don’t have any feeling in my feet(…)I told the doctor not to put it in there and they still did it.(…)I was really cross after it because I thought all that pain.’ (Sarah, FG2, line 460–465) Sarah spoke about feeling excluded when a doctor spoke discretely to her mother: ‘No but it does happen to people like they feel they’re left out.(…)Today,(…)a doctor was explaining something to me and he was just about to leave and when he was just about to leave he said to my mum, “If you want to ask a question I can come back” so I kind of thought is he doing that because he doesn’t want me to hear my mother asking the question.’ (Sarah, FG2, line 612 & 619–622) |

Note: Rachel, Laura, Sarah, and Darren are pseudonyms (participants aged 11–15 years).

Box 3. Take-home messages for healthcare professionals (HCPs).

Focus group participants provided take-home messages about how HCPs, could deliver high-quality child-centred care:

‘Explain.’ (Laura, FG2, line 409) ‘Explain it in a child friendly way.’ (Sarah, FG2, line 411) ‘Because if the child is really young it has to be explained in a different way. At an age you’re able to understand [or HCPs will] scare them.’ (Sarah, FG2, line 658–663)

‘They should explain what they are going to do before they do it, and like(…)always say who they are and what they’re gonna do(…)[and at] what time(…), and explain what was gonna happen and why(…).’ (Rachel, FG1, line 498–510)

‘I think just tell everyone together.(…)Because like telling your mum and dad first you’ll see the expression on their face and then you’re already gonna know.’ (Laura, FG2, line 651–654)

‘Always like ask [children] do you have any questions(…)ask [to check understanding].’ (Sarah, FG2, line 388 & 416–417)

‘Whenever [children] come in, try and treat them like nicer, em.’ (Darren, FG1, line 992) ‘Like treat them the same as everybody else so they all feel the same.’ (Rachel, FG1, line 993)

Note: Rachel, Laura, Sarah, and Darren are pseudonyms (participants aged 11–15 years)

Discussion

CADs’ experiences were influenced by HCPs forming relationships and involving them: engendering trust and involving CADs satisfied them, made them happier when undergoing procedures and treatments, and better able to confide. HCPs did this by being personable, wise, and sincere, relating at a personal level, bringing CADs into conversations and decisions, and speaking in child-friendly ways. Conversely, not relating to or involving CADs, communicating ineffectively by using inappropriately technical language or positioning CADs as ‘piggy-in-the-middle’ between HCPs and parents resulted in CADs being fearful, angry, resistant and disengaged.

These findings add to earlier studies, which identified intimate relationships,55–57 trust55 and involvement,48 58 as important ingredients of caring well for CADs. They corroborate a recent systematic review of decision-making experiences, which found that HCPs (and parents) made adolescents feel fearful, anxious and depersonalised when they withheld information or denied involvement.58 Parents had a significant influence on HCPs’ experiences in our study too, by facilitating or impeding communication. Overcoming parental primacy, over-involvement, over-protectiveness,48 55 58 and wishes to withhold information remains a substantial challenge for HCPs.55

Strengths and limitations

Our synthesis advances understanding of CADs’ experiences of HCPs because of its comprehensiveness, analysis of interrelationships between the nature, origins and effects of trust and involvement, and its advocacy for CADs’ autonomy. It provides a blueprint for CCC, which has, until now, largely depended on theory and expert consensus rather than empirical evidence.8 Our findings endorse the concept and importance of CCC, while showing how much work is needed to put this principle into practice. Our review was innovative in the way it used phenomenology, a theory that is highly relevant to the topic, to inform a rigorous interpretive synthesis. This allows us to go beyond cataloguing publications and draw empirically supported conclusions about how HCPs could care more effectively for CADs. This, we suggest, is a significant contribution to the scholarship of evidence synthesis.

As with most qualitative syntheses, we present a broad overview, whose findings are potentially transferable across a range of clinical contexts. We took an iterative approach to article selection and ensured adequate time for rigorous interpretive analysis; while some evidence may have been published since we searched the databases, this is an inherent limitation in research that goes to such lengths to analyse a huge evidence-base and synthesise information. We doubt that this materially affects our conclusions since the nature of human relationships are unlikely to change in 12 months. Consulting with stakeholders, while obviously desirable, is often omitted from scoping reviews.59 Our consultation sample was admittedly small and relatively homogenous, but participants spoke informatively about their experiences, which helped consolidate and authenticate the findings.

Our conclusions are susceptible to both publication and interpretation bias because more emotive material tends to attract greater attention. This limitation is partially offset by our rigorous adherence to methodological standards. Another limitation, imposed by the non-specific nature of studies and inexplicit reporting of metadata by primary authors, is that we could not analyse how different types of HCP, or participants’ ages or illnesses, affected CADs’ experiences. Restricting the scope to English language publications excluded non-English speaking children from distinct cultural groups. This is an important topic for future study.

Implications for policy, research and practice

Our findings add impetus to the movement to design, deliver and further characterise child-centred healthcare,60 which has important implications for HCPs, educators, researchers and policy-makers. Our empirical augmentation of this conceptual model supports these initiatives. To achieve the vision of CCC, there is a need for communication strategies, training, assessments and feedback (from CADs, specifically) at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels of health professions education. Further research will be needed to address the long-term sustainability and effectiveness of CCC. Evidence on how healthcare policy, practice and legislation can influence child-centred approaches is also long overdue. Further research could also examine how age, illness, gender and the cultures of different professions influence the drive for CCC. Further implications for practice include the need for HCPs to examine how professional boundaries between themselves and CADs are characterised, and consider how best to respect CADs’ preferences when it goes against ‘best practice’.

bmjopen-2021-054368supp007.pdf (77KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Richard Fallis, for his assistance with the search strategy, Richard McCrory, for his advice in the early stages of this review, and Jenne McDonald, for attending the first stakeholder consultation.

Footnotes

Twitter: @gaildavison9, @richardlconn, @ProfTimD

Collaborators: None.

Contributors: GD conceived the review, sought approvals, secured funding, led the execution and led the write-up. GD, AT and RC completed the focus groups. MK, RC, AT and TD assisted with data selection, analyses and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by the Charitable Funds Department, Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children, by award of a PhD Research Fellowship, received by GD. Grant number 71817005. Funders had no direct involvement with conceptualisation or completion.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi: 10.5061/dryad.t76hdr817.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Gained.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for focus groups was obtained from the Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland (reference: 19/NI/0070), while research governance was obtained from the Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, Northern Ireland. Queen’s University Belfast (QUB) sponsored the study in accordance with the UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care.

References

- 1.Wolfe A. Institute of medicine report: crossing the quality chasm: a new health care system for the 21st century. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 2001;2:233–5. 10.1177/152715440100200312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raleigh V, Foot C. Getting the measure of quality: opportunites and challenges. London: The King’s Fund; 2010: 9–12. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/getting-measure-quality [Accessed 04/09/2020]. 978 1 85717 590 5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open 2013;3:e001570. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I. Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational study. BMJ 2001;322:468–72. 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulter A, Fitzpatrick R, Cornwell J. Measures of patients’ experience in hospital: purpose, methods and uses. London: The King’s Fund, 2009: 1–32. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Point-of-Care-Measures-of-patients-experience-in-hospital-Kings-Fund-July-2009_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Picker . Influence, inspire, empower: impact report 2017-2018. Oxford: Picker, 2018. https://www.picker.org/about-us/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter B, Bray L, Dickinson A. Child-Centred nursing: promoting critical thinking. London: Sage Publications, Ltd, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyne I, Holmström I, Söderbäck M. Centeredness in healthcare: a concept synthesis of Family-centered care, Person-centered care and child-centered care. J Pediatr Nurs 2018;42:45–56. 10.1016/j.pedn.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pritchard Kennedy A. Systematic ethnography of school-age children with bleeding disorders and other chronic illnesses: exploring children’s perceptions of partnership roles in family-centred care of their chronic illness. Child Care Health Dev 2012;38:863–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sommer D, Pramling Samuelsson I, Hundeide K. Early childhood care and education: a child perspective paradigm. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 2013;21:459–75. 10.1080/1350293X.2013.845436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Söderbäck M, Coyne I, Harder M. The importance of including both a child perspective and the child’s perspective within health care settings to provide truly child-centred care. J Child Health Care 2011;15:99–106. 10.1177/1367493510397624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes JC, Bamford C, May C. Types of centredness in health care: themes and concepts. Med Health Care Philos 2008;11:455–63. 10.1007/s11019-008-9131-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coyne I, Hallström I, Söderbäck M. Reframing the focus from a family-centred to a child-centred care approach for children’s healthcare. J Child Health Care 2016;20:494–502. 10.1177/1367493516642744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNICEF . The United Nations convention on the rights of the child. New York: UNICEF, 1990: 5. https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/unicef-convention-rights-child-uncrc.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.GMC . 0-18 years: guidance for all doctors. London: GMC, 2007. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/0_18_years_english_0418pdf_48903188.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livesley J, Long T. Children's experiences as hospital in-patients: voice, competence and work. messages for nursing from a critical ethnographic study. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:1292–303. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lachman P. Redefining the clinical gaze. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:888–90. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doukrou M, Segal TY. Fifteen-minute consultation: communicating with young people-how to use HEEADSSS, a psychosocial interview for adolescents. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2018;103:15–19. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levetown M, and the Committee on Bioethics . Communicating with children and families: from everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics 2008;121:e1441–60. 10.1542/peds.2008-0565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Care Quality Comission . 2016 Children and young people’s inpatient and day case survey: Statistical release. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Care Quality Comission, 2017. https://www.cqc.org.uk/about-us [Google Scholar]

- 21.Care Quality Commission . Children and young people’s inpatient and day case survey 2014: National results. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Care Quality Commission, 2015: 1–78. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20150626_cypsurvey_results_tables.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linney M. RCPCH responds to CQC’s Children and young people’s inpatient and day case survey, 2017. Available: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/news-events/news/rcpch-responds-cqcs-children-young-peoples-inpatient-day-case-survey

- 23.Lowes L, Eddy D, Channon S, et al. The experience of living with type 1 diabetes and attending clinic from the perception of children, adolescents and carers: analysis of qualitative data from the depicted study. J Pediatr Nurs 2015;30:54–62. 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NHS England . Nhs improvement and coalition for personalised care. A co-production model. coalition for personalised care. London: NHS England, 2020: 1. https://coalitionforpersonalisedcare.org.uk/resources/a-co-production-model/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kennedy I. Getting it right for children and young people: overcoming cultural barriers in the NHS so as to meet their needs. London: Department of Health (DH), 2010: 125. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health . The development of a patient reported experience measure for paediatrics patients (0-16 years) in urgent and emergency care: research report, 2012. Available: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/patient-reported-experience-measure-prem-urgent-emergency-care

- 27.Roper L, Sherratt FC, Young B, et al. Children's views on research without prior consent in emergency situations: a UK qualitative study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022894. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Royal College of Paediatrics and Health . State of child health. London: Royal College of Paediatrics and Health; 2017: 1–134. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-05/state_of_child_health_2017report_updated_29.05.18.pdf [Accessed 01 July 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) . State of child health England-Two years on. London: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH), 2019: 1–24. www.rcpch.ac.uk/state-of-child-health [Google Scholar]

- 30.NHS Digital . Nhs outcomes framework 2020/21: indicator and domain summary tables. London: NHS Digital, 2020. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-outcomes-framework/august-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute of Clinical Excellence . Babies, children and young people’s experience of healthcare, Guideline Scope. London: National Institute of Clinical Excellence, 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-ng10119/documents/final-scope [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hargreaves DS, Viner RM. Children's and young people's experience of the National health service in England: a review of national surveys 2001-2011. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:661–6. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hargreaves DS, Sizmur S, Pitchforth J, et al. Children and young people's versus parents' responses in an English national inpatient survey. Arch Dis Child 2018;103:486–91. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manen M. Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-Giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. London & New York: Routledge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci 2010;5:1–9. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:1291–4. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gillespie H, Kelly M, Duggan S, et al. How do patients experience caring? scoping review. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:1622–33. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. The SAGE Handbook of qualitative research. 5th edition. London: SAGE, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davison G, Kelly MA, Thompson A, et al. Children’s and adolescents’ experiences of healthcare professionals: scoping review protocol. Syst Rev 2020;9. 10.1186/s13643-020-01298-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Booth A. "Brimful of STARLITE": toward standards for reporting literature searches. J Med Libr Assoc 2006;94:421–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P. Scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. Adelaide, Australia: JBI, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hardin AP, Hackell JM, COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE AND AMBULATORY MEDICINE . Age limit of pediatrics. Pediatrics 2017;140:e20172151. 10.1542/peds.2017-2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sawyer SM, McNeil R, Francis KL, et al. The age of paediatrics. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2019;3:822–30. 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30266-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.UNICEF . Adolescents overview. New York: UNICEF, 2019: 1. https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/overview/ [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2000;320:50–2. 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tjaden L, Tong A, Henning P, et al. Children's experiences of dialysis: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:395–402. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 51.QRS International . NVivo qualitative data analysis software. Doncaster Victoria, Australia: QRS International, 2021: 1. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scherer KR, Shuman V. The grid meets the wheel: assessing emotional feeling via self-report. In: Fontaine JJR, Scherer KR, Soriano C, eds. Components of emotional meaning: a sourcebook. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013: 315–38. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Plutchik R. The nature of emotions: human emotions have deep evolutionary roots, a fact that may explain their complexity and provide tools for clinical practice. Am Sci 2001;89:344–50. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gillespie H, Kelly M, Gormley G. How can tomorrow’s doctors be more caring? A phenomenological investigation. Med Educ 2018;52:1052–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coyne I, Amory A, Gibson F, et al. Information-sharing between healthcare professionals, parents and children with cancer: more than a matter of information exchange. Eur J Cancer Care 2016;25:141–56. 10.1111/ecc.12411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lewis P, Kelly M, Wilson V, et al. What did they say? How children, families and nurses experience ‘care’. Journal of Children's and Young People's Nursing 2007;1:259–66. 10.12968/jcyn.2007.1.6.27660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Corsano P, Majorano M, Vignola V, et al. Hospitalized children’s representations of their relationship with nurses and doctors. J Child Health Care 2013;17:294–304. 10.1177/1367493512456116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jordan A, Wood F, Edwards A, et al. What adolescents living with long-term conditions say about being involved in decision-making about their healthcare: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of preferences and experiences. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:1725–35. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, et al. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods 2014;5:371–85. 10.1002/jrsm.1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ford K, Campbell S, Carter B, et al. The concept of child-centered care in healthcare: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2018;16:845–51. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aalsma MC, Brown JR, Holloway ED, et al. Connection to mental health care upon community reentry for detained youth: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:117. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alex MR, Ritchie JA. School-aged children’s interpretation of their experience with acute surgical pain. J Pediatr Nurs 1992;7:171–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anderson SM, Wray J, Ralph A, et al. Experiences of adolescent lung transplant recipients: A qualitative study. Pediatr Transplant 2017;21:e12878. 10.1111/petr.12878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ångström-Brännström C, Norberg A, Jansson L. Narratives of children with chronic illness about being Comforted. J Pediatr Nurs 2008;23:310–6. 10.1016/j.pedn.2007.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ångström-Brännström C, Norberg A. Children undergoing cancer treatment describe their experiences of comfort in interviews and Drawings. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2014;31:135–46. 10.1177/1043454214521693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beresford BA, Sloper P. Chronically ill adolescents’ experiences of communicating with doctors: a qualitative study. Journal of Adolescent Health 2003;33:172–9. 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00047-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boyd JR, Hunsberger M. Chronically ill children coping with repeated hospitalizations: their perceptions and suggested interventions. J Pediatr Nurs 1998;13:330–42. 10.1016/S0882-5963(98)80021-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown JR, Holloway ED, Akakpo TF, et al. “Straight up”: enhancing rapport and therapeutic alliance with previously-detained youth in the delivery of mental health services. Community Ment Health J 2014;50:193–203. 10.1007/s10597-013-9617-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carney T, Murphy S, McClure J, et al. Children’s views of hospitalization: an exploratory study of data collection. J Child Health Care 2003;7:27–40. 10.1177/1367493503007001674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheng S-F, Foster RL, Hester NO, et al. A qualitative inquiry of Taiwanese children’s pain experiences. J Nurs Res 2003;11:241–50. 10.1097/01.JNR.0000347643.27628.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheng Y-C, Huang C-Y, Wu W-W, et al. The lived experiences of Aboriginal adolescent survivors of childhood cancer during the recovering process in Taiwan: a descriptive qualitative research. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016;22:78–84. 10.1016/j.ejon.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Christofides E, Dobson JA, Solomon M, et al. Heuristic decision-making about research participation in children with cystic fibrosis. Soc Sci Med 2016;162:32–40. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Clift L, Dampier S, Timmons S. Adolescents’ experiences of emergency admission to children’s wards. J Child Health Care 2007;11:195–207. 10.1177/1367493507079561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Colver A, Pearse R, Watson RM, et al. How well do services for young people with long term conditions deliver features proposed to improve transition? BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:337. 10.1186/s12913-018-3168-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Corsano P, Cigala A, Majorano M, et al. Speaking about emotional events in hospital: the role of health-care professionals in children emotional experiences. J Child Health Care 2015;19:84–92. 10.1177/1367493513496912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Coyne I, Hayes E, Gallagher P. Giving children a voice: investigation of children’s experiences of participation in consultation and decision-making in Irish hospitals. The Stationary Office, Dublin: Office of the Minister for Children; 2006. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/25352/ [Accessed 16 August 2019]. 0-7557-1662-0. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coyne I. Children’s experiences of hospitalization. J Child Health Care 2006;10:326–36. 10.1177/1367493506067884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Coyne I. Consultation with children in hospital: children, parents' and nurses' perspectives. J Clin Nurs 2006;15:61–71. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01247.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Coyne I, Conlon J. Children’s and young people’s views of hospitalization: ‘It’s a scary place’. Journal of Children's and Young People's Nursing 2007;1:16–21. 10.12968/jcyn.2007.1.1.23302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Coyne I, Gallagher P. Participation in communication and decision-making: children and young people's experiences in a hospital setting. J Clin Nurs 2011;20:2334–43. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03582.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Coyne I, Kirwan L. Ascertaining children’s wishes and feelings about hospital life. J Child Health Care 2012;16:293–304. 10.1177/1367493512443905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Coyne I, Amory A, Kiernan G, et al. Children's participation in shared decision-making: children, adolescents, parents and healthcare professionals' perspectives and experiences. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2014;18:273–80. 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Coyne I, McNamara N, Healy M, et al. Adolescents’ and parents’ views of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) in Ireland. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2015;22:561–9. 10.1111/jpm.12215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Curtis P, Northcott A. The impact of single and shared rooms on family-centred care in children's hospitals. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:1584–96. 10.1111/jocn.13485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Das A, Detels R, Javanbakht M, et al. Living with HIV in West Bengal, India: perceptions of infected children and their caregivers. AIDS Care 2017;29:800–6. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1227059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Day C, Carey M, Surgenor T. Children's key concerns: piloting a qualitative approach to understanding their experience of mental health care. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006;11:139–55. 10.1177/1359104506056322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dell'Api M, Rennick JE, Rosmus C. Childhood chronic pain and health care professional interactions: shaping the chronic pain experiences of children. J Child Health Care 2007;11:269–86. 10.1177/1367493507082756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]