Artificial intelligence is becoming increasingly important in surgical care delivery. Predictive analytic and patient phenotyping systems augment personalized, patient-centered decision-making and improve care.1 Robotic surgical platforms and autonomous microrobots have the potential to change the way surgeons are trained and operations are performed.2

Accountants who were late adopters of calculators failed to capitalize on potential gains in accuracy and efficiency; similarly, surgeons who are late adopters of artificial intelligence may forfeit potential gains in consistently providing high-value care. All surgeons should be familiar with the core principles and primary applications of artificial intelligence in surgery; some should become experts.3,4 The profession of surgery and its patients benefit from surgeon expertise in architectural engineering, basic science, biomedical engineering, business administration, economics, education, epidemiology, health services, informatics, law, public health, and more. Surgeons with expertise in artificial intelligence methods and applications are needed to lead its safe, effective clinical implementation in surgery.

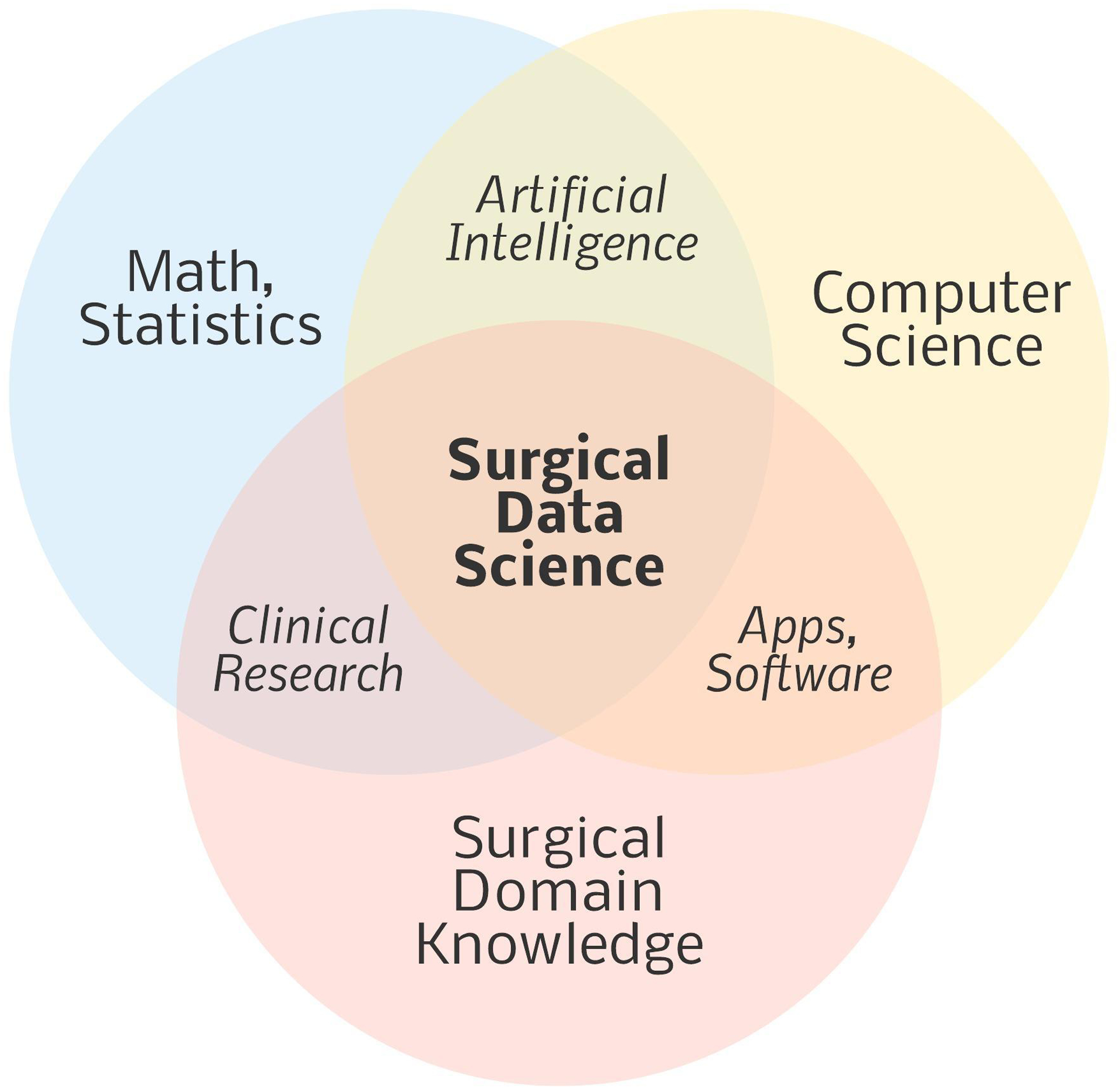

As innate leaders of multidisciplinary clinical teams, especially in the operating room, most surgeons have the organizational and group management skills necessary to lead the clinical implementation of artificial intelligence in surgery.3 In addition, surgeons inherently understand a bane of clinical informatics: uncertainty in clinical data. Values recorded in research databases or electronic health records are almost never accompanied by an indicator of uncertainty, or the probability that the value is inaccurate. Machine learning algorithms may not recognize the uncertainty inherent to findings of cervical lymphadenopathy and subjective fevers documented in a medical student note from an Oncology clinic, but an experienced clinician easily understands the uncertainty inherent to these values. Similarly, a clinician easily recognizes that when a young, healthy patient being discharged home has missing respiratory device values, the patient was probably breathing room air; when the same values are missing for a patient in an intensive care unit receiving a propofol infusion with a static respiratory rate of 12, the patient was probably on mechanical ventilation. Surgeons can use their inherent understanding of nuances in clinical data to develop smarter models. In addition, most surgeons already have most of the foundational knowledge necessary to understand and apply artificial intelligence in surgery by gaining expertise in data science, an inter-disciplinary field that incorporates three realms: 1) mathematics and statistics, 2) domain knowledge, and 3) computer science, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Surgical data science incorporates three major, overlapping disciplines.

Mathematics and Statistics

Success on the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) step tests, and American Board of Surgery In-Training and Qualifying Examinations requires working knowledge of mathematics and statistics. Therefore, most surgeons gain a foundational understanding of the relevant concepts and applications during training. As data science and artificial intelligence become increasingly important in surgical care delivery, it may become advantageous to place a greater emphasis on mathematics and statistics in maintenance of certification processes.

Domain Knowledge

Deep understanding of domain subject matter is necessary to ensure that artificial intelligence models will succeed when applied in real-world scenarios. Data scientists and clinicians without surgical practice experience should not be expected to truly understand the clinical nuances of surgical care, many of which are learned from experience. Historically, artificial intelligence applications in surgery have emerged from collaborations between data scientists and surgeons. These collaborations might be more fruitful if interested surgeons took the additional step of becoming data scientists by gaining computer science skills.

Computer Science

Surgeons are accustomed to developing technical and non-technical skills that require deep commitment to academic rigor and deliberate practice. Surgeons can translate these principles in learning to read and write programming code, or computer-readable instructions for performing specific tasks. Resources for learning computer programming are readily available to the general public. The Microsoft-owned code-hosting site GitHub has more than 40 million users that share code with collaborators and the public. The Python programming language, which is popular for machine learning applications, follows human thought processes in a flexible, yet logical fashion, and is readily learned via free, on-line courses offered by Harvard and other reputable universities and organizations. Using these resources, surgeons can learn to comprehend and speak the language of computer programming and apply collective, collaborative human knowledge and skill in solving problems that are beyond the reach of traditional additive and linear models.

Training Pathways and Future Directions

To provide all surgeons with working knowledge of data-driven decision-making and artificial intelligence applications in surgery, informatics training can be incorporated in surgical residency curricula, as described at the University of California, Los Angeles.7 To provide a pathway for some surgeons to become data scientists, surgical residents can gain board certification in Clinical Informatics from the American Board of Medical Specialties through a 24-month program that can be completed during professional development time imbedded within surgical training programs that allot five years for standard clinical training and also offer two or more additional years of training for professional development.5 Surgeons and surgical trainees can also seek Masters and PhD degrees in clinical informatics, biomedical informatics, and other data science-oriented domains. The National Library of Medicine supports formal training in biomedical informatics and data science at 16 US institutions.6

As artificial intelligence and data science become increasingly important in delivering optimal surgical care, surgeons should maintain a working knowledge of relevant concepts. Some surgeons should take the additional step of becoming data scientists and steer clinical implementation processes. To become data scientists, surgeons need only to reinforce their foundational knowledge in mathematics and statistics and apply their unique domain knowledge to computer science applications, which are readily learned through established training pathways. Beyond the pragmatism of this approach, surgeons may discover a natural predilection for data science given its similarities with surgery: both disciplines apply art and science in establishing knowledge and techniques that are shared among colleagues to drive innovation and performance improvement, and professional environments are simultaneously competitive and collaborative, fostering the relentless pursuit of perfection through deliberate practice. These elements can fuel the passion and productivity of surgeons with data science expertise in leading the safe, effective clinical implementation of artificial intelligence in surgery.

Acknowledgements

AB was supported by R01 GM110240 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). AB was supported by Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center Award P50 GM-111152 from the NIGMS. TJL was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23 GM140268. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Wijnberge M, Geerts BF, Hol L, et al. Effect of a Machine Learning-Derived Early Warning System for Intraoperative Hypotension vs Standard Care on Depth and Duration of Intraoperative Hypotension During Elective Noncardiac Surgery: The HYPE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyashita S, Guitron S, Yoshida K, Shuguang L, Damian DD, Rus D. Ingestible, controllable, and degradable origami robot for patching stomach wounds. Paper presented at: 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 16–21 May 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao J, Forsythe R, Langerman A, Melton GB, Schneider DF, Jackson GP. The Value of the Surgeon Informatician. J Surg Res. 2020;252:264–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyu HG, Doherty GM, Landman AB. Surgical Informatics: Defining the Role of Informatics in the Current Surgical Training Paradigm. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(1):9–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The American Board of Preventive Medicine Has Obtained Approval from the American Board of Medical Specialties’ (ABMS) to Offer Surgical Residents Mid-Residency Training Programs in Clinical Informatics (MRTP). Available at: https://www.theabpm.org/2019/03/19/the-american-board-of-preventive-medicine-has-obtained-approval-from-the-american-board-of-medical-specialties-abms-to-offer-surgical-residents-mid-residency-training-programs-in-clinical-informat/. Accessed July 17, 2020.

- 6.NLM’s University-based Biomedical Informatics and Data Science Research Training Programs. Available at: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/ep/GrantTrainInstitute.html. Accessed July 17, 2020.

- 7.Singer JS, Cheng EM, Baldwin K, Pfeffer MA, Comm UHPI. The UCLA Health Resident Informaticist Program - A Novel Clinical Informatics Training Program. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2017;24(4):832–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]