Abstract

Chronic wounds are a considerable health burden with high morbidity and poor rates of healing. Colonisation of chronic wounds by bacteria can be a significant factor in their poor healing rate. These bacteria can develop antibiotic resistance over time and can lead to wound infections, systemic illness, and occasionally amputation. When a large number of micro‐organisms colonise wounds, they can lead to biofilm formation, which are self‐perpetuating colonies of bacteria closed within an extracellular matrix, which are poorly penetrated by antibiotics. Platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) is an autologous blood product rich in growth factors and cytokines that are involved in an inflammatory response. PRP can be injected or applied to a wound as a topical gel, and there is some interest regarding its antimicrobial properties and whether this can improve wound healing. This study aimed to evaluate the in vitro bacteriostatic effect of PRP. PRP was collected from healthy volunteers and processed into two preparations: activated PRP—activated with calcium chloride and ethanol; inactivated PRP. The activity of each preparation against Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermis was evaluated against a control by three experiments: bacterial kill assay to assess planktonic bacterial growth; plate colony assay to assess bacterial colony growth; and colony biofilm assay to assess biofilm growth. Compared with control, both preparations of PRP significantly inhibited growth of planktonic S aureus and S epidermis. Activated PRP reduced planktonic bacterial concentration more than inactivated PRP in both bacteria. Both PRP preparations significantly reduced bacterial colony counts for both bacteria when compared with control; however, there was no difference between the two. There was no difference found between biofilm growth in either PRP against control or against the other preparation. This study demonstrates that PRP does have an inhibitory effect on the growth of common wound pathogens. Activation may be an important factor in increasing the antimicrobial effect of PRP. However, we did not find evidence of an effect against more complex bacterial colonies.

Keywords: antimicrobial therapy, chronic wounds, platelet‐rich plasma

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic wounds are often colonised by micro‐organisms, which may reduce their potential to heal. In up to 90% of wounds, these micro‐organisms develop into biofilms. 1 , 2 Biofilm formation occurs when micro‐organisms create an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) that traps floating bacteria in a three‐dimensional aggregation, allowing the biofilm to firmly adhere to a wound surface. This protective arrangement makes the enclosed micro‐organisms robust against attack 3 and antibiotic penetration. 4 Protection against antibiotics is enhanced by the slower metabolic rate of certain biofilm cells. Bacterial cells found at the centre of the biofilm arrangement tend to exist at a lower metabolic rate than more peripheral cells, which in turn pass on nutrients through the EPS to the central cells via diffusion. The central cells, known as “persister” cells, are in essence metabolically inactive, meaning that antibiotics have limited effect. 5 , 6 Furthermore, biofilm bacteria can develop direct antibiotic resistance, 7 probably due to the overexpression of resistant genes. 8

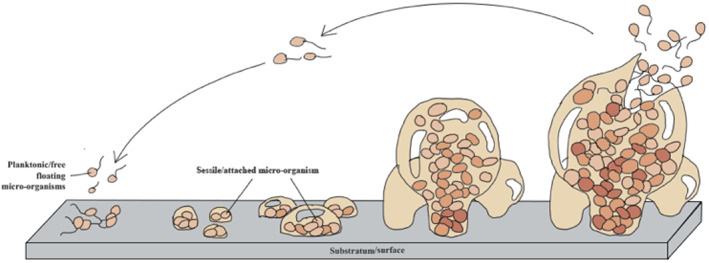

Figure 1 illustrates the process of biofilm formation. Initially bacteria adhere to a surface that offers the optimum conditions for survival through attachment of membrane structures such as pili and interaction between cell surface molecules such as lectins. 9 Once stable, the microbe will undergo multiplication and the adhesion will become irreversible. 10 , 11 , 12 This is self‐perpetuated by cell‐to‐cell chemical signalling between bacteria known as quorum sensing, which leads to an increase in cell concentration. Once a certain concentration of bacteria is reached, the cell signalling leads to the formation of EPS, which binds the cells together in a three‐dimensional structure. This extracellular matrix provides protection as well as allows diffusion of nutrients. 13 When a biofilm colony is established, fragments of the colony as well as individual cells can detach and embolise to a new site elsewhere in the body.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram illustrating the developmental stages of biofilm formation: (a) adhesion/to a surface; (b) multiplication of microorganisms; (c) micro‐colony formation; (d) maturation of biofilms; (e) dispersal and detachment leading to continuous repetition of the cycle

When wounds are treated with platelet‐rich plasma (PRP), there may be an antimicrobial effect that contributes to enhanced wound healing. Platelets are known to have antimicrobial action against individual bacteria and biofilms. They accumulate immediately at the site of endothelial damage caused by microbial colonisation and play an essential natural defensive role in the body's fight against infection. Alpha granules are rich in growth factors (GF) and cytokines, which encourage an inflammatory response, recruiting immune cells to the site of injury to attack pathogens. 14 When platelets are exposed to bacteria, they participate in bacterial co‐adhesion resulting in bacterial sequestration and phagocytosis of bacteria. 15 Platelets also support neutrophils in creating cell‐to‐cell interactions with endothelial cells and leucocytes. 16 A diabetic infected wound rat model demonstrated that platelets are able to shield immortalised human keratinocytes from damage caused by bacteria, stimulate anti‐inflammatory cytokines, and cell proliferation, while at the same time inhibiting pro‐inflammatory cytokines. 17

Alpha granules also contain molecules known as platelet microbicidal proteins/peptides (PMPs), which when released have an antimicrobial effect. 18 PMPs can act as chemokines, recruiting immune cells, and exaggerating a host response against pathogens. Certain PMPs, known as kinocidins, can also exert a direct antimicrobial effect, killing bacteria as well as coordinating the immune response. 19 , 20 Common PMPs are platelet factor‐4 (PF‐4)/CXCL‐4, neutrophil‐activating protein‐2 (NAP‐2)/CXCL‐7, interleukin‐8/CXCL‐8, regulated upon activation normal T‐cell expressed (RANTES)/CCL‐5, and thymosin beta‐4.

NAP‐2/CXCL7 (thrombocidin‐1 and thromocidin‐2) is bactericidal against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Lactococcus lactis, and also fungicidal for Cryptococcus neoformans. 19 PF‐4/CXCL‐4 also exhibits bactericidal activity against S aureus and Salmonella thyphimurium. 20 Platelet alpha granules also secrete Fc receptor for immunoglobulin, complement factors C3a and C5a (C3a: increased vascular permeability; C5a: chemoattractant), as well as numerous chemokine toll‐like receptors (TLRs), which are capable of provoking reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). The host defence mechanism against infectious agents is also facilitated by ROS and RNS. 21 Furthermore, myeloperoxidase, which produces hypohalous acid, is found in alpha granules and has antioxidant and antimicrobial actions. 21

PRP may work as an adjunct to conventional antibiotic therapy in wound infection or in some cases as an alternative due to the potentially lower risk of drug resistance. 22 PRP may also assist in reducing colonisation in uninfected chronic wounds. Several studies, summarised in Supplementary Table 1, have demonstrated that PRP may inhibit the growth of both gram‐positive and gram‐negative bacteria. 15 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 One study also demonstrated an inhibitory effect against S aureus, but not E coli or Pseudomonas aureginosa, in a diabetic rat model, suggesting that the effect may be carried over to diabetes. 17 PRP also has an inhibitory effect on the growth of the fungus Candida albicans 23 and the pathogenic yeast C neoformans. 18

In addition to platelets, other cells found within PRP may also contribute to an antimicrobial effect. Leucocytes are found within PRP and the composition can be altered to include more or less during processing. Some studies in Supplementary Table 1 have found that leucocyte‐rich PRP may have a more significant antibacterial response possibly due to leucocyte‐platelet aggregation causing an enhanced inflammatory response although the evidence is not conclusive. Complement found within PRP may also contribute to the antibacterial response. 30

1.1. Study aims

Several studies have found that PRP has a direct bacteriostatic effect on common wound pathogens. However, the literature is limited, with few published studies and no evidence that has directly evaluated the effect of PRP on biofilms. Furthermore, no studies have compared the effect of activation on the antimicrobial effects of PRP against an inactivated control.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the antimicrobial effect of PRP on bacterial colonies of common wound pathogens and to assess whether activation of the PRP affected this activity.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Institutional ethical approval was obtained for the study and all experiments were carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Blood was collected from three male volunteers. No volunteer had any significant past medical history, had platelet disorders, or was taking anticoagulants.

2.1. PRP preparation

To produce PRP, whole blood (52 mL) was obtained via peripheral venipuncture and was combined with 8 mL of adenosine citrate dextrose acid (ACD‐A). PRP with a haematocrit of 8% was produced using the Angel PRP processing device (Arthrex, Naples, Florida), which utilised an automated two‐step centrifugation method. Following centrifugation, an automated 3‐sensor ultraviolet flow cytometry method sensed cell‐specific wavelengths of light for platelets, red blood cells, and platelet poor plasma (PPP), allowing their separation into sterile compartments.

10 mL of PRP from each participant was divided into two 5 mL aliquots. One aliquot underwent activation with calcium chloride (CaCl2) and ethanol using an ActiVat device (Arthrex, Naples, Florida). This device combined 12 mL of PPP with 0.13 mL of 10% CaCl2 and 2.4 mL of 10% ethanol. The mixture was shaken with the reaction taking place on glass resin beads found within the device to encourage activation of thrombin. The mixture was left for 15 minutes and was then combined with the PRP at a 1:3 ratio (1.67 mL additive: 5 mL PRP). One aliquot remained inactivated. The activated and inactivated PRP samples were tested against a phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) control as outlined in Table 1. Supernatant from activated and inactivated PRP was also tested against a PBS control using the plate colony assay.

TABLE 1.

A summary of the test variables

| Test variable | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Phosphate‐buffered solution (PBS) |

| 2 | Activated PRP |

| 3 | Inactivated PRP |

After collection, PRP samples were used immediately in the experiments. Samples were centrifuged using a microcentrifuge (PicoFuge, Stratagene, California) and vortexed to ensure proper mixing prior to use. For the supernatant experiment, separate PRP samples were collected and stored in an incubator with humidified air at 37°C for 1 hour. Supernatant was then extracted, placed in Eppendorf tubes, and stored in a freezer at −80°C until ready for experimentation. All samples were thawed and used in experiments within 2 weeks of storage. Supernatant samples were thawed only once to prevent excess growth factor activation with repeat freeze–thaw cycles and were centrifuged and vortexed prior to use.

2.2. Bacteria preparation

The strains used in this study were S aureus NCTC 8235‐4 and Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62A strain (ATCC 35984), both of which have been used extensively in previous laboratory studies and have been shown to form biofilms. 39 , 40 Bacterial stock vials were stored at −80°C and once ready for use were thawed at room temperature and then applied to Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar plates to grow bacterial cultures. Once bacteria were streaked onto plates, they were kept in a shaking incubator at 37°C for 24 hours under continuous rotation at 200 rpm (SciQuip, Newtown, UK). Gram stains were then performed on the plates to assess for colonial morphology and purity. Cultures were then kept in an incubator until ready for use.

For each experiment, fresh bacterial cultures were prepared as follows. A single colony of S aureus and S epidermidis were added to two sterile 50 mL screw cap tubes containing 15 mL of BHI broth. A third tube containing BHI broth‐only acted as a control. The tubes were transferred to the shaking incubator at 200 rpm at 37°C for 16 to 18 hours. Bacteria were then removed and pipetted into cuvettes in a 1:10 ratio with BHI broth (900 μL of BHI broth: 100 μL of bacterial inoculum) and were mixed 10 times with a pipette. 1 mL of the BHI control broth was added to a cuvette to act as a control. The samples were then passed through a spectrophotometer to obtain a measure of concentration of bacteria—colony‐forming units/ml (CFU/mL). The samples were then diluted (based on the optical density readout) with BHI broth to gain the desired concentration prior to use.

2.3. Bacterial kill assay

This experiment was designed to assess the effect on planktonic bacteria at 1 and 4 hours after contact. This assay is considered the best practice to quantitatively analyse antimicrobial activity over time and has been used in multiple previous studies.

Five experimental samples were prepared in 15 mL screw cap tubes for each bacteria as follows—1500 μL BHI, 250 μL bacterial inoculum, and 250 μL of test variable These samples were prepared to achieve an inoculum concentration of 1 × 105 CFU/mL, which is the laboratory marker for diagnosis of infection. Tubes were then placed in the shaking incubator at 200 rpm at 37°C. At 1 and 4 hours, the tubes were removed, vortexed for 10 seconds, and aliquots of 200 μL were removed and placed into one row of a 96‐well plate. Serial dilutions were performed to obtain eight concentrations. A 20 μL aliquot of each dilution was applied to half of a BHI agar plate and spread evenly using L‐shaped spreaders. Plates were incubated for 24 hours and bacterial colonies were then counted and concentration was expressed as 10 Log CFU/mL. Bacteriostatic activity was defined as no increase in growth of bacteria from the original inoculum concentration. Bactericidal was defined as a reduction of at least 99.9% of the total count of CFU/mL in the original inoculum. Data generated from the experiment were mean concentration of bacteria at 1 and 4 hours (10 Log CFU/mL). Concentrations for each preparation at each time point were compared using statistical analysis.

2.4. Plate colony assay

This experiment was designed to examine the effect of PRP against established bacterial colonies. The protocol for this assay was adapted from the Kirby‐Bauer disk diffusion method as recommended by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). 41 Overnight bacterial cultures were prepared as in step 2.2 and were then diluted to a concentration of 1 × 105 CFU/mL after measuring with the spectrophotometer. A sample of each inoculum was then applied evenly to agar plates using a sterile swab and left for 15 minutes. A 50 μL volume of each test variable was applied to 6‐mm‐diameter sterile filter paper discs (180 μm thick, 11 μm pore size), and the discs were then applied to each bacterial lawn. After 15 minutes, the plates were placed in an aerobic incubator at 37°C for 24 hours. Standardised images of each plate were taken and the number of colonies present within 18 mm of the embedded discs were counted using ImageJ (National Institute of Health) to ensure more consistent results when compared to manual counting. 42 The mean numbers of colonies counted for each preparation were compared using statistical analysis.

2.5. Colony biofilm assay

This experiment was designed to examine the effect of PRP against biofilm colonies. The protocol for this assay was modified from a validated biofilm growing protocol, 43 which ensures that bacterial colonies once formed are less likely to detach. This ensures that variations in colony counts are more likely due to cell death rather than detachment.

Overnight bacterial cultures were prepared and were then diluted to a concentration of 1 × 105 CFU/mL after measuring with the spectrophotometer. Sterile 25‐mm nitrocellulose membrane filter paper discs were placed in agar plates using sterile forceps. The discs were inoculated with 5 μL of each inoculum, and these were then incubated upside down to prevent condensation at 37°C for 24 hours. After 24 hours, 100 μL of each test variable was applied to the discs and the plates were transferred back to the incubator for a further 24 hours. Each disc was then added to a sterile 50 mL screw cap tubes with 5 mL of sterile PBS and six 3‐mm glass beads. The tubes were vortexed twice for 60 seconds to detach the bacteria. Aliquots of 200 μL were removed and placed into one row of a 96‐well plate. Serial dilutions were performed to obtain eight concentrations. A 20 μL aliquot of each dilution was applied to half of a BHI agar plate and spread evenly using L‐shaped spreaders. Plates were incubated for 24 hours and bacterial colonies were then counted and concentration was expressed as 10 Log CFU/mL. The use of solid agar plates to grow biofilm colonies in this method allows growth of a fractal colony with numerous morphologies via the diffusion limited aggregation process. 44 Data generated from the experiment were mean concentration of bacteria (10 Log CFU/ml). Concentrations for each preparation were compared using statistical analysis.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data were presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Comparison of means (bacterial concentration and colony count) was undertaken using an unpaired t‐test or a Mann‐Whitney U test for non‐parametric data. A P value of <.05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

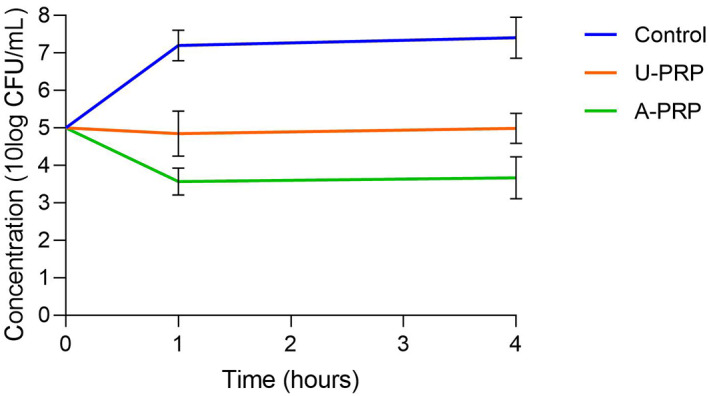

3.1. Bacterial kill assay (planktonic bacteria)

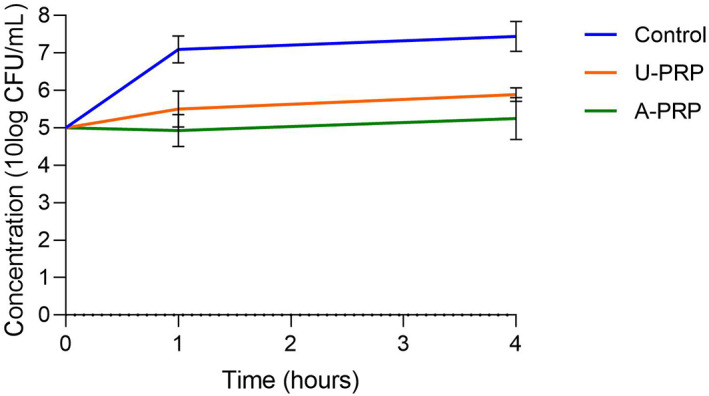

Using both S aureus and S epidermidis, both activated and inactivated PRP showed a significant reduction (P < .05) in bacterial concentrations compared with control at both 1 and 4 hours. Activated PRP also showed a significant reduction at both 1 and 4 hours compared with inactivated PRP. The results are summarised in Figures 2 and 3. The results for S aureus indicate that both PRP samples are bacteriostatic—with activated showing the greater effect—and with the maximum effect coming in the first hour, but neither PRP is bactericidal. The results for S epidermidis show that both PRP samples are relatively bacteriostatic, again with the maximum effect coming within 1 hour, but less so compared with their effect on S aureus.

FIGURE 2.

Change in planktonic Staphylococcus aureus concentrations from baseline to 4 hours

FIGURE 3.

Change in planktonic Staphylococcus epidermidis concentrations from baseline to 4 hours

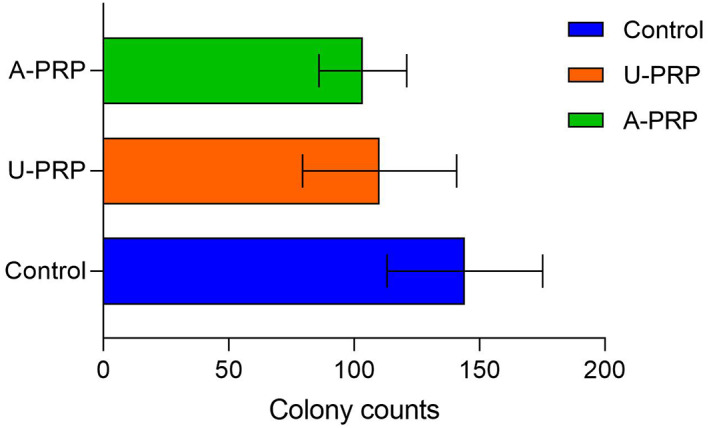

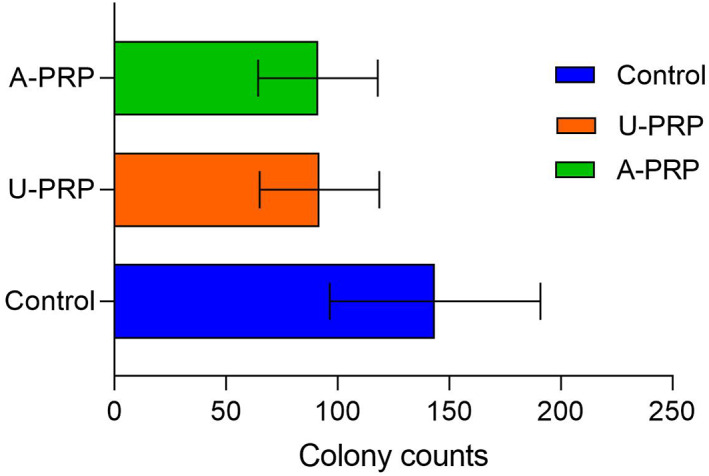

3.2. Plate colony assay (bacterial colony)

The mean numbers of S aureus colonies identified in both activated (103.44 ± 17.47) and inactivated (110.11 ± 30.74) were significantly lower when compared with control (144.11 ± 31.02). However, there was no significant difference between types of PRP Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Mean number of Staphylococcus aureus colonies on plate colony assay

The mean numbers of S epidermidis colonies identified in both activated (91.22 ± 26.82) and inactivated (91.88 ± 26.81) were significantly lower when compared with control (143.66 ± 47.20). However, there was no significant difference between types of PRP Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Mean number of Staphylococcus epidermidis colonies on plate colony assay

When PRP supernatant from both activated and inactivated PRP was tested against control using a plate colony assay, there was no difference between the number of colonies observed between any of the groups.

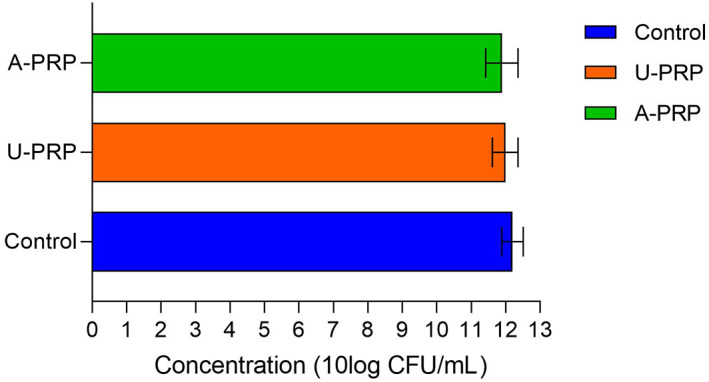

3.3. Colony biofilm assay (biofilm)

For the S aureus colony biofilm assay, there were no significant differences between activated PRP (11.89 ± 0.47 log CFU/mL), inactivated (11.99 ± 0.37 log CFU/mL), and control (12.20 ± 0.31 log CFU/mL. These results also indicate an increase in the number of bacterial colonies from the baseline inoculum concentration of 5 log CFU/mL over 24 hours in all three groups. Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Mean Staphylococcus aureus biofilm concentration

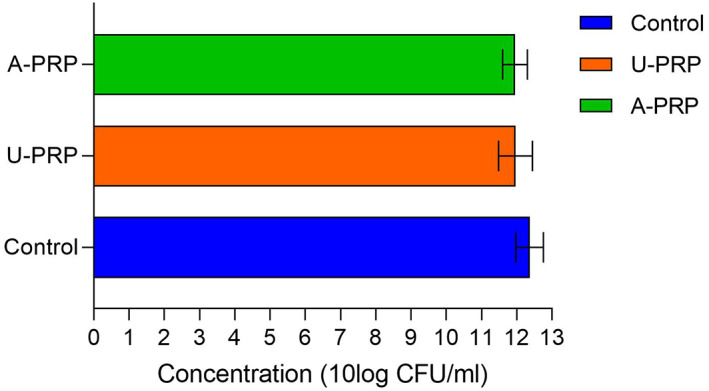

For the S epidermidis assay, there were also no significant differences between activated PRP (11.95 ± 0.35 log CFU/mL), inactivated (11.97 ± 0.48 log CFU/mL) or control (12.37 ± 0.39 log CFU/mL). Again all three groups showed an increase in colony concentration from the inoculum baseline Figure 7.

FIGURE 7.

Mean Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm concentration

4. DISCUSSION

Bacterial colonisation and infection of chronic wounds can have a significant impact on the wound healing process and are likely to contribute to poor healing rates. The use of PRP as a wound healing treatment is becoming more popular, and there is reasonable evidence to show that PRP confers an antimicrobial effect, which in turn may assist in wound healing. Several previous studies have found that PRP can reduce the growth of S aureus and S epidermidis bacteria in vitro. However, no previous studies have investigated whether activation of a PRP preparation can affect its antimicrobial activity against planktonic bacteria, bacterial colonies, or biofilm in a single study.

Our findings suggest that both inactivated and activated PRP are bacteriostatic against both strains of bacteria when tested against simple planktonic bacteria. The maximum effect is seen within 1 hour, which is supported by the findings of a previous study, 25 but the effect is also maintained up to 4 hours. Neither of the preparations showed a strong enough inhibitory effect to be classed as bactericidal with the log CFU/mL remaining similar to the baseline inoculum concentration. However, no study in the literature has previously demonstrated a bactericidal effect against S aureus and S epidermidis, with only one study demonstrating bactericidal activity against Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus agalactiae, and Streptococcus oralis. 34 The bacteriostatic effect of PRP was also demonstrated in this study by the plate colony assay, which illustrated that both preparations of PRP significantly reduced the number of bacterial colonies compared with control.

Our findings also found that activation of PRP with calcium chloride and ethanol significantly improves the bacteriostatic effect on planktonic bacteria. Two previous studies have shown that activation with thrombin (autologous and bovine) shows improved bacteriostatic effect when compared against inactivated PRP 26 and PPP. 36 However, ours is the first study to demonstrate the antimicrobial effect of activation with calcium chloride and ethanol on a preparation of PRP against different strains of bacterial culture. The literature suggests that activation is likely to confer an enhanced antimicrobial effect due to the increased release of alpha granules, which contain PMPs and kinocidins. PMPs enhance the immune response by recruiting immune cells to the site of infection and exaggerate the inflammatory response and are therefore unlikely to have a significant effect in vitro. However, some PMPs such as NAP‐2/CXCL7 and PF‐4/CXCL‐4 have been shown to have a direct bactericidal effect. 19 , 20 Kinocidins also have a direct bactericidal effect and may contribute to the effect in vitro. The finding that PRP supernatant known to be rich in growth factors had no effect on colony growth in this study (even when activated) also supports the theory that it is the platelets and the PMPs that provide the antimicrobial effect. However, our study found that the enhanced effect of activation was not seen in more complex bacterial colonies. This may be due to the more complex structure of these bacteria, which are less vulnerable to direct topical application of PRP without an immune response to provide additional antimicrobial support.

This finding is further demonstrated in the lack of effect of both PRP preparations against biofilms. Ours is the first study to evaluate an activated and inactivated PRP preparation against more complex biofilm cultures. The lack of effect is most likely due to the fact that biofilms are known to be up to ×1000 more resilient to antimicrobial agents than planktonic bacteria and therefore require much higher concentrations to show an effect. 45 , 46 This is because biofilm bacteria are able to protect themselves within the EPS. The antimicrobial agents secreted by alpha granules are less likely to penetrate the biofilm cultures because of the role of diffusion‐limited transport of substances through the biofilm EPS, which dilutes them as they pass through the colony. Our study also used relatively low concentrations of PRP against biofilms, which would have limited the amount of PMPs and kinocidins that could take effect. One previous study has demonstrated that there is a clear “window of opportunity” to take effect against biofilms, between the initial adhesion and irreversible binding of the bacteria, when a treatment has a chance of eradication. 2 During this period, the bacteria remain susceptible; however, once developed they are difficult to penetrate. Therefore, topical PRP treatment seems unlikely to be effective against established biofilms. In clinical practice, PRP may be more effective in more established colonies when used along with antibiotic therapy.

4.1. Limitations

One limitation of the study was the examination of PRP against only two bacterial strains in isolation. S aureus and S epidermidis are commonly involved in chronic wound colonisation, biofilm formation, and antibiotic resistance. 47 , 48 However, chronic wounds are often colonised by a myriad of organisms, which unite in a complex biofilm structure. Therefore, the testing against these bacteria alone is not directly representative of the clinical environment. in vitro models for multi‐species biofilms do exist; however, there is a lack of consensus over the accuracy and clinical applicability of these models. 49 In order to effectively test PRP against established biofilms, in vivo animal models or clinical studies would be required.

Another limitation is the small number of preparations of PRP tested. There have been several different PRP preparations evaluated by previous authors for their antimicrobial effect. There are also a plethora of commercial devices and methods of PRP preparation and activation, 50 meaning the numbers of permutations in preparation are infinite. To our knowledge, no previous study has investigated antimicrobial effect of PRP harvested by the Angel device or activated by the ActiVat device. This study could have varied the platelet concentration, the haemocrit, and the activation method of the PRP; however, only a randomised controlled trial of the many different PRP preparations will provide more conclusive answers.

5. CONCLUSION

This study has demonstrated that PRP has a bacteriostatic effect on S aureus and S epidermidis when tested against planktonic bacteria and bacterial colonies. Activation of the PRP with calcium chloride and ethanol also gives an enhanced effect against planktonic bacteria. However, there was no effect of either PRP preparation against more complex biofilm colonies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No author has any conflict of interest

Supporting information

Supplementary Table 1 Summary of the literature regarding the antimicrobial effect of platelets/PRP. Key: Inhibited the growth of bacteria (+); failed to inhibit (−); not tested (). GAS—Group A Streptococcus; MRSA—Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MRSE—Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis; MSSA—Methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; MSSE—Methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus epidermidis; VRE—Vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The sources of funding are the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Academic Clinical Fellow (ACF) programme; and Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP).

Smith OJ, Wicaksana A, Davidson D, Spratt D, Mosahebi A. An evaluation of the bacteriostatic effect of platelet‐rich plasma. Int Wound J. 2021;18:448–456. 10.1111/iwj.13545

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Percival SL, McCarty SM, Lipsky B. Biofilms and wounds: an overview of the evidence. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015;4(7):373‐381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Attinger C, Wolcott R. Clinically addressing biofilm in chronic wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2012;1(3):127‐132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clinton A, Carter T. Chronic wound biofilms: pathogenesis and potential therapies. Lab Med. 2015;46(4):277‐284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Costerton JW. Introduction to biofilm. Int J Antimicrobial Agents. 1999;11(3):217‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Proctor RA, von Eiff C, Kahl BC, et al. Small colony variants: a pathogenic form of bacteria that facilitates persistent and recurrent infections. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(4):295‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wood TK, Knabel SJ, Kwan BW. Bacterial persister cell formation and dormancy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(23):7116‐7121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bowler PG. Antibiotic resistance and biofilm tolerance: a combined threat in the treatment of chronic infections. J Wound Care. 2018;27(5):273‐277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ciofu O, Rojo‐Molinero E, Macià MD, Oliver A. Antibiotic treatment of biofilm infections. APMIS. 2017;125(4):304‐319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arciola CR, Campoccia D, Montanaro L. Implant infections: adhesion, biofilm formation and immune evasion. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(7):397‐409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jamal M, Tasneem U, Hussain T, Andleeb S. Bacterial biofilm: its composition, formation and role in human infections. RRJMB. 2015;4(3):1‐14. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Flemming HC, Wingender J, Szewzyk U, Steinberg P, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S. Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14(9):563‐575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Laverty G, Gorman SP, Gilmore BF. Biomolecular mechanisms of staphylococcal biofilm formation. Future Microbiol. 2013;8(4):509‐524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McConoughey SJ, Howlin R, Granger JF, et al. Biofilms in periprosthetic orthopedic infections. Future Microbiol. 2014;9(8):987‐1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yeaman MR. Platelets in defense against bacterial pathogens. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(4):525‐544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Różalski M, Bartlomiej M, Sadowska B, Paszkiewicz M, Więckowska‐Szakiel M, Różalska B. Antimicrobial/anti‐biofilm activity of expired blood platelets and their released products. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 2013;67:321‐325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klinger MHF, Jelkmann W. Review: role of blood platelets in infection and inflammation. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22(9):913‐922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li T, Ma Y, Wang M, et al. Platelet‐rich plasma plays an antibacterial, anti‐inflammatory and cell proliferation‐promoting role in an in vitro model for diabetic infected wounds. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:297‐309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tang YQ, Yeaman MR, Selsted ME. Antimicrobial peptides from human platelets. Infect Immun. 2002;70(12):6524‐6533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krijgsveld J, Zaat SA, Meeldijk J, et al. Thrombocidins, microbicidal proteins from human blood platelets, are C‐terminal deletion products of CXC chemokines. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(27):20374‐20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yeaman MR, Yount NY, Waring AJ, et al. Modular determinants of antimicrobial activity in platelet factor‐4 family kinocidins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768(3):609‐619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yeaman MR. Platelets: at the nexus of antimicrobial defence. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12(6):426‐437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cetinkaya RA, Yenilmez E, Petrone P, et al. Platelet‐rich plasma as an additional therapeutic option for infected wounds with multi‐drug resistant bacteria: in vitro antibacterial activity study. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019;45(3):555‐565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aggour R, Gamil L. Antimicrobial effects of platelet‐rich plasma against selected oral and periodontal pathogens. Pol J Microbiol. 2017;66(1):31‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Anitua E, Alonso R, Girbau C, Aguirre JJ, Muruzabal F, Orive G. Antibacterial effect of plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF(R)‐Endoret(R)) against Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis strains. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(6):652‐657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li H, Li B. PRP as a new approach to prevent infection: preparation and in vitro antimicrobial properties of PRP. J Vis Exp. 2013;74:50351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bielecki TM, Gazdzik TS, Arendt J, Szczepanski T, Kròl W, Wielkoszynski T. Antibacterial effect of autologous platelet gel enriched with growth factors and other active substances. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89‐B(3):417‐420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mariani E, Filardo G, Canella V, et al. Platelet‐rich plasma affects bacterial growth in vitro. Cytotherapy. 2014;16(9):1294‐1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen L, Wang C, Liu H, Liu G, Ran X. Antibacterial effect of autologous platelet rich gel derived from subjects with diabetic dermal ulcers in vitro. J Diabetes Res. 2013;2013:269527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Drago L, Bortolin M, Vassena C, Romano CL, Taschieri S, Del Fabbro M. Plasma components and platelet activation are essential for the antimicrobial properties of autologous platelet‐rich plasma: an in vitro study. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burnouf T, Chou ML, Wu YW, Su CY, Lee LW. Antimicrobial activity of platelet (PLT)‐poor plasma, PLT‐rich plasma, PLT gel, and solvent/detergent‐treated PLT lysate biomaterials against wound bacteria. Transfusion. 2013;53(1):138‐146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Singh R, Dhayal RK, Sehgal PK, Rohilla RK. To evaluate antimicrobial properties of platelet rich plasma and source of colonization in pressure ulcers in spinal injury patients. Ulcers. 2015;2015:1‐7. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Badade P, Mahale S, Panjwani A, Vaidya P, Warang A. Antimicrobial effect of platelet‐rich plasma and platelet‐rich fibrin. Indian J Dent Res. 2016;27(3):300‐304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cieslik‐Bielecka A, Bold T, Ziolkowski G, Pierchala M, Krolikowska A, Reichert P. Antibacterial activity of leukocyte‐ and platelet‐rich plasma: an in vitro study. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9471723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Drago L, Bortolin M, Vassena C, Taschieri S, Del Fabbro M. Antimicrobial activity of pure platelet‐rich plasma against microorganisms isolated from oral cavity. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Intravia J, Allen DA, Durant TJ, et al. In vitro evaluation of the anti‐bacterial effect of two preparations of platelet rich plasma compared with cefazolin and whole blood. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4(1):79‐84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moojen DJ, Everts PA, Schure RM, et al. Antimicrobial activity of platelet‐leukocyte gel against Staphylococcus aureus . J Orthop Res. 2008;26(3):404‐410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yang LC, Hu SW, Yan M, Yang JJ, Tsou SH, Lin YY. Antimicrobial activity of platelet‐rich plasma and other plasma preparations against periodontal pathogens. J Periodontol. 2015;86(2):310‐318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li H, Hamza T, Tidwell JE, Clovis N, Li B. Unique antimicrobial effects of platelet rich plasma and its efficacy as a prophylaxis to prevent implant‐associated spinal infection. Adv Healthc Mater. 2013;2(9):1277‐1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O'Neill AJ. Staphylococcus aureus SH1000 and 8325‐4: comparative genome sequences of key laboratory strains in staphylococcal research. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2010;51(3):358‐361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shapiro JA, Nguyen VL, Chamberlain NR. Evidence for persisters in Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62a planktonic cultures and biofilms. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60(Pt 7):950‐960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. EUCAST . Antimicrobial susceptibility testing EUCAST disk diffusion method, Version 8.0. 2020. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Disk_test_documents/2020_manuals/Manual_v_8.0_EUCAST_Disk_Test_2020.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2020.

- 42. Grishagin IV. Automatic cell counting with ImageJ. Anal Biochem. 2015;473:63‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Merritt JH, Kadouri DE, O'Toole GA. Growing and analyzing static biofilms. Current protocols in microbiology, Bridgewater, NJ: Wiley; 2005. Chapter 1: Unit‐1B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang X, Wang G, Hao M. Modeling of the Bacillus subtilis bacterial biofilm growing on an agar substrate. Comput Math Methods Med. 2015;2015:581829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Olson ME, Ceri H, Morck DW, Buret AG, Read RR. Biofilm bacteria: formation and comparative susceptibility to antibiotics. Can J Vet Res. 2002;66(2):86‐92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Keren I, Kaldalu N, Spoering A, Wang Y, Lewis K. Persister cells and tolerance to antimicrobials. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;230(1):13‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Diekema DJ, Pfaller MA, Schmitz FJ, et al. Survey of infections due to staphylococcus species: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the Western Pacific region for the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program, 1997–1999. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(Supplement_2):S114‐S132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Otto M. Staphylococcus epidermidis—the 'accidental' pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(8):555‐567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bahamondez‐Canas TF, Heersema LA, Smyth HDC. Current status of in vitro models and assays for susceptibility testing for wound biofilm infections. Biomedicine. 2019;7(2):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Oudelaar BW, Peerbooms JC, Huis In't Veld R, et al. Concentrations of blood components in commercial platelet‐rich plasma separation systems. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(2):479‐487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1 Summary of the literature regarding the antimicrobial effect of platelets/PRP. Key: Inhibited the growth of bacteria (+); failed to inhibit (−); not tested (). GAS—Group A Streptococcus; MRSA—Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MRSE—Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis; MSSA—Methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; MSSE—Methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus epidermidis; VRE—Vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.