Abstract

A post-exposure cohort study in Hiroshima and Nagasaki reported that low-dose exposure to radiation heightened the risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), such as stroke and myocardial infarction, by 14–18% per Gy. Moreover, the risk of atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries reportedly increases with radiation therapy of the chest, including breast and lung cancer treatment. Cellular senescence of vascular endothelial cells (ECs) is believed to play an important role in radiation-induced CVDs. The molecular mechanism of age-related cellular senescence is believed to involve genomic instability and DNA damage response (DDR); the chronic inflammation associated with senescence causes cardiovascular damage. Therefore, vascular endothelial cell senescence is believed to induce the pathogenesis of CVDs after radiation exposure. The findings of several prior studies have revealed that ionizing radiation (IR) induces cellular senescence as well as cell death in ECs. We have previously reported that DDR activates endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase, and NO production promotes endothelial senescence. Endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) is a major isoform expressed in ECs that maintains cardiovascular homeostasis. Therefore, radiation-induced NO production, a component of the DDR in ECs, may be involved in CVDs after radiation exposure. In this article, we describe the pathology of radiation-induced CVD and the unique radio-response to radiation exposure in ECs.

Keywords: radiation-induced cardiovascular disease, endothelial cells (ECs), nitric oxide (NO), eNOS, DNA damage response (DDR)

INTRODUCTION

Ionizing radiation (IR) causes acute and chronic injuries in living organisms. Radiation-induced cellular injury is mainly due to DNA damage in the nucleus [1]. To repair DNA lesions by IR, the DNA damage response (DDR) coordinates the activation of cell-cycle checkpoints, appropriate DNA repair pathways and numerous other responses [2–4]. However, interactions between the DDR for recovery and networks of kinase cascades within and across pathways remain largely elusive.

Radiation incidents in Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Marshallese and Chernobyl have shown that the injury pattern in exposed individuals depends on the dose of IR [5–8]. Recently, a significant number of studies have demonstrated that exposure of the cardiovascular system, including the heart and vasculature, to radiation increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [9–12]. These side effects of radiation exposure have been reported in cases of chest irradiation for the treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma [13–15], lung cancer [10, 16] and breast cancer [10, 17–19]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying radiation-induced CVD are not well understood [20, 21].

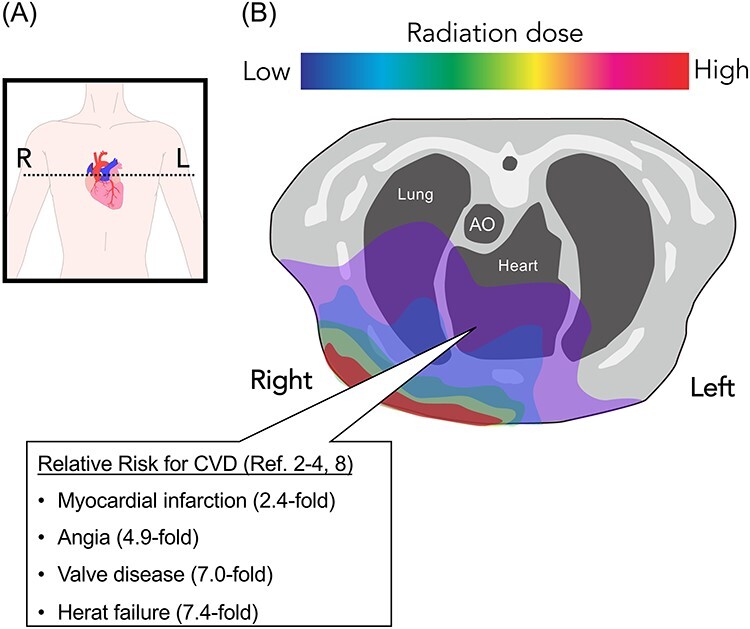

Accumulated epidemiological evidence indicates that several CVDs occur after radiation exposure (Fig. 1). Pericarditis may occur in a significant section of the myocardial tissue at relatively high doses (>50 Gy) of radiation. Nevertheless, radiation-induced CVD can occur at low doses (>0.5 Gy) as well. In fact, myocardial damage can be diagnosed at doses lower than those inducing pericarditis [22]. A cohort study involving Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors showed the potential magnitude of CVD risk [5]. The number of radiation-related deaths due to circulatory diseases was approximately a third as large as that of the deaths due to cancer. Long-term effects at low doses are crucial because these patients may be exposed to radiation by multiple computed tomography scans, other relatively high-dose diagnostic medical procedures, and radiotherapy that impacts the heart. Moreover, a systematic review of CVD with radiation therapy demonstrated that cancer survivors experience approximately 10% relative increase in coronary artery disease per Gy of mean heart dose, which translates into one to two excess deaths per 1,000 patients treated in 10 years [23]. Furthermore, another meta-analysis showed that high dose radiation to the heart may increase the incidence of cardiac event; subsequently, CVD after IR contributes to the worse overall survival [24]. Overall, a significant increase in the risk of CVD has been observed at a dose lower than the accepted tolerance dose for the heart [25]. The DDR of endothelial cells (ECs) is one of the molecular pathologies of radiation-induced CVD. Furthermore, radiation-induced nitric oxide (NO) production generates a unique DDR in ECs and induces senescence after radiation exposure. In this article, we focus on the role of ECs in CVD and the radio-response to IR with respect to the implications of radiation-induced CVD.

Fig. 1.

Radiation exposure in the cardiovascular system. (A) Schematic for horizontal plane of radiation dose painting. The dotted line indicates transverse plane of (B). (B) Schematic for radiation exposure to the cardiovascular system. Look up table indicates radiation dose (e.g. Red = high dose region, Blue = low dose regions); the heart received a low, but significant, dose of irradiation.

Endothelial dysfunction causes CVD

A monolayer of ECs constitutes the vascular endothelium that coats the inner surface of arteries, veins and capillaries [26]. On the innermost side of the vasculature, ECs sense information pertaining to the circulatory system, including hormone secretion/circulation and the intensity of blood flow. In addition, ECs maintain contact with chemical compounds and cells in the blood. Because ECs form a barrier between the blood and the tissues, in addition to performing endocrine functions, they play an important physiological role in vascular homeostasis, including maintenance of blood fluidity, regulation of vascular tone, modulation of pro-inflammatory molecule production, inflammatory immune responses and angiogenesis [27]. Vasoconstriction and vasodilation are key functions required for meeting the cellular requirement of oxygen levels. ECs produce NO to regulate vascular tension. Increases in cGMP and cAMP levels by NO activate cellular kinase cascades, such as protein kinase A (PKA) or protein kinase G (PKG), leading to smooth-muscle relaxation. Furthermore, NO is a major anti-platelet agent that boosts cAMP levels in platelets [26]. NO-dependent dysfunction of ECs is widely recognized as an initial step toward CVD. Thus, the role of NO is not limited to the control of cardiac or vascular contractility but extends to the regulation of cardiovascular tissue [28].

Under inflammatory conditions, vasoconstrictors (angiotensin II, endothelin-1 (ET-1) and prostaglandin H2) and vasodilators (NO and prostaglandin I2) control the permeability of ECs to infiltrating leukocytes and modulate the coagulation process. Mediators of inflammation (Interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor, vascular endothelial growth factor and others) contribute to these phenotypes that manifest characteristic EC behaviors associated with inflammation [29]. To respond to these inflammatory mediators, ECs produce vasodilators and vasoconstrictors that regulate the permeability of blood vessels. Therefore, ECs play an important role in physiology and regulate the pathology of circulatory systems. In addition to the modulation of blood circulation, ECs play a central role in angiogenesis by invading the tissue to form new vessels [30]. Although ECs maintain a quiescent state under physiological conditions, tissue injury or hypoxia augments their proliferation and invasiveness. This process is closely related to several physiological events, such as wound healing, inflammatory disorders, cancer development and diabetes mellitus. Thus, EC dysfunction is an important risk factor for CVD [31, 32].

Aging and oxidative stress induces senescence in ECs

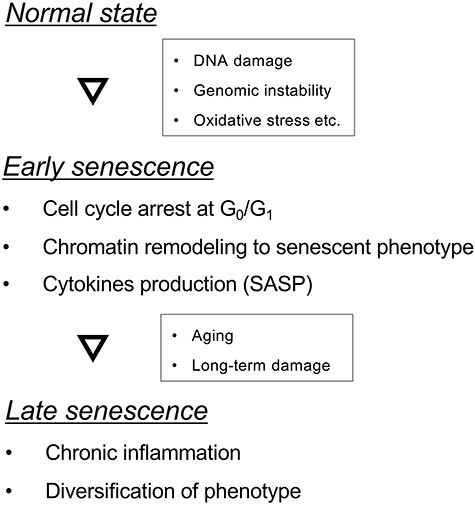

As described in the previous section, endothelial dysfunction leads to CVD and accumulation of senescent ECs has been reported in age-related diseases [33]; additionally, EC senescence contributes to arterial stiffness, atherosclerosis, hypertension, stroke and coronary artery disease [34, 35]. In vitro cellular senescence is attributed to telomere dysfunction at the Hayflick cell division limit (replicative senescence). In addition, stress response to intrinsic and extrinsic insults, including oncogenic activation, oxidative and genotoxic stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, irradiation and chemotherapeutic agents also induces senescence known as stress-induced premature senescence [36, 37]. Cellular senescence in vivo can be categorized as early and late (Fig. 2). Early senescence seems to be a programmed process that is triggered in response to external stressors and contributes to tissue homeostasis. In contrast, late senescence may result from long-term persistent damage and is often associated with detrimental processes such as aging. EC senescence has been found to play a key role in vascular aging, leading to the initiation, progression and advancement of CVD. Senescent ECs become flatter and enlarged, with a polyploid nucleus, indicating the loss of vital functions, such as barrier integrity, angiogenic property and cytokine production. For example, senescent ECs show low NO production, increased ET-1 release and elevated inflammation [34]. Thus, endothelial senescence contributes to the development and progression of CVD. Along with the loss of function due to endothelial senescence, senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) also plays an important role in age-related CVD. Cytokines, proteins and other factors secreted by ECs trigger a chronic inflammatory status mediated by SASP. Normally, it is presumed that SASP activates the immune system to eliminate senescent ECs; however, long-term persistence of senescent ECs and their specific SASP can drive the pathological development of CVD.

Fig. 2.

Process of cellular senescence. Stepwise development of cellular senescence induced by an external stressor. Abbreviation: SASP, senescence-associated secretory phenotype.

Oxidative stress is another risk factor for CVD [38]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxygen-containing highly reactive molecules are by-products of cellular metabolism and play significant roles in cell signaling and homeostasis [39]. Various environmental stresses, such as ultraviolet radiation increase cellular ROS levels. The significant forms of ROS in the cardiovascular system are superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals. ROS react readily with lipids, proteins, carbohydrates and nucleic acids. This may result in significant damage to biomolecules, termed oxidative stress; intensive oxidative stress induces EC senescence and death. Endothelial senescence caused by ROS is believed to initiate various CVD pathologies. Several atherosclerosis risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes and smoking, can cause elevation in the ROS levels in ECs [38]. Oxidative stress induces endothelial dysfunction by upregulating adhesive molecules to recruit inflammatory cells. In addition, ROS can react to low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol particles and impair their function [40]. Hepatocytes synthesize LDL, which is circulated throughout the body to supply cholesterol to the organs. Cholesterol plays a pivotal role in the maintenance of cellular membrane and cellular metabolism; however, ROS can oxidize LDL, resulting in structural complications. As the uptake of oxidized LDL is difficult for cells, LDL accumulates in the blood circulation, and this could possibly be the preliminary stage of atherogenesis. Furthermore, numerous cardiovascular risk factors inhibit the dimerization of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) monomers, leading to improper electronic transmission [35]. Electron leakage from the eNOS monomer in turn induces superoxide production instead of NO production, amplifying oxidative stress. Moreover, increased ROS can intensify genomic instability, driving cellular senescence [41–43]. Thus, aging and oxidative stress potentiate the pathological development of CVD by inducing cellular senescence.

DDR-induced endothelial dysfunction after radiation exposure

In the previous sections, we have discussed cardiovascular disorders caused by endothelial dysfunction. Cellular senescence and oxidative stress are also induced as a consequence of radio-response [44, 45]. Radiation exposure damages all components of the cardiovascular system, including the pericardium, myocardium, valves and coronary arteries. However, relatively few studies have demonstrated the radio-response of ECs. Classically, cardiovascular tissue, mainly the heart tissue, is considered radio-resistant. ECs should possess higher radio-sensitivity because cells with high duplication rate are characterized by higher radiosensitivity. Thus, although muscle and connective tissue are resistant to radiation exposure, ECs could be affected; dysfunction in the endothelium that controls muscles and connective tissues may lead to loss of function in the entire circulation, thereby causing CVD.

Radiation exposure causes significant DNA damage and oxidative stress in ECs, leading to cell senescence and death. DNA damage activates a massive cellular signaling network termed the DDR. The primary transducer of DNA double-strand breaks is the protein kinase ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), which phosphorylates numerous key players in various branches of the DDR. Further, ATM and Rad3-related protein (ATR) kinase are activated primarily by single-strand breaks that are generated following the induction of DNA adducts or during the processing of double-stranded breaks or collapsed replication forks. ATM and ATR have functional redundancy because both can phosphorylate serine/threonine residues, followed by glutamine [46]. More than 700 proteins are phosphorylated by ATM/ATR [47]. Downstream of ATM/ATR, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is involved in directing cellular responses and regulating cell functions, including proliferation, gene expression, differentiation, mitosis, cell survival and apoptosis. Phosphorylation of Ser15 of p53 protein by ATM is a typical cellular reaction, and this post-translational modification enhances the stability of the p53 protein, leading to cell-cycle arrest after IR [48–50]. ATM/ATR phosphorylate the MAPK subfamily: extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 MAPK (p38) [51, 52]. Two upstream MAPK kinases, MAPK kinase (MAPKK) 1 and MAPKK2, are activated by IR. Phosphorylation of these upstream MAPKs induces a radio-response to radiation exposure via activator protein 1 (AP-1) transcription factor. ERK is activated in response to IR in an ATM- and MEK1-dependent manner and is involved in apoptosis [53, 54]. Similarly, JNK is activated by IR in an ATM-dependent manner and may induce pro-apoptotic functions; however, its substrates or its relationship with other kinases recruited at the sites has not been elucidated [55, 56]. Additionally, p38 MAPK enzymatic activity is induced in response to DNA damage. Activated p38 phosphorylates CDC25B, facilitating the initiation of G2/M arrest [57, 58].

It is well known that DDR and genomic instability, due to the accumulation of DNA damage, causes cellular senescence [45, 59–62]. In addition, IR induces early senescence in the exposed ECs [60]. Since endothelial senescence is a pathogenesis of age-related CVD, radiation-induced senescence may be involved in the pathogenesis of CVD post-radiation exposure. Moreover, cellular senescence induces cytokine production by SASP. In age-related CVD, cytokines play an important role in the disease pathology. Cytokines orchestrate complex mesenchymal, epithelial and immune interactions that influence tissue damage as well as restore integrity and homeostasis by promoting angiogenesis and tissue regeneration or replacement by fibrosis. It is well established that radiation induces inflammatory transcription factors such as NF-κB, AP-1, and Signal Transducers and Activator of Transcription (STAT) and various types of cytokines [63]. The main effect of radiation is manifested by increased DNA damage. However, this radiation-induced cytokine production causes additional damage by amplifying the radiation-induced cellular response and immune reaction and by intensifying tissue inflammation. In addition to cytokines, radiation-induced damage causes the secretion or release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [64]. DAMPs are molecules released upon cellular stress or tissue injury and are regarded as endogenous danger signals because they induce potent inflammatory responses by activating the innate immune system during non-infectious inflammation. Recently, emerging evidence has indicated that DAMPs play a key role in the pathogenesis of human diseases (e.g. autoimmune diseases, osteoarthritis, neurodegenerative diseases and CVD) and may be valuable biomarkers for inflammatory diseases, including age-related senescence [65]. The consequences induced by DAMPs include vascular damage after radiation exposure, interstitial fluid accumulation, inflammatory cell infiltration and the formation of a lesion with a pro-oxidant microenvironment that is hostile to pathogens and cells alike, with a spatially and temporally expanded ‘danger’ zone.

Through DAMP and cytokine production, multiple layers of self-amplifying feedback control circuits are created that prolong responses for a long period after the initial radiation-induced ionization events. Endothelial senescence due to radiation exposure impairs the regulation of blood flow and barrier function. Therefore, radiation-induced senescence of ECs is a major risk factor for CVD following radiation exposure. In addition to CVD, EC senescence by DDR is proposed to be involved in the progression of Alzheimer’s neuropathology [66]. Thus, understanding the DDR of ECs is crucial for evaluating radiation-induced side effects in multiple organs with blood vessels.

NO production as a component of DDR in ECs

Unlike most cell types, vascular ECs exert their physiological functions in an NO-dependent manner [67]. NO regulates the functions of ECs via two distinct pathways: an indirect pathway involving the activation of PKA/PKG signaling and a direct pathway involving adduction to other biomolecules [28]. In addition to lipids and DNA, NO can also modify proteins, resulting in post-translational modifications that can alter their function [68–70]. NO, the smallest signaling molecule, is produced by NOS, which has three different isoforms [67]. These enzymes catalyze the conversion of L-arginine and oxygen to NO with the aid of several co-factors. Neuronal NOS (nNOS, NOS1) is constitutively expressed in neurons, and inducible NOS (iNOS, NOS2) is expressed in several cell types in response to inflammation. eNOS (NOS3) is a major isoform expressed in ECs and is involved in cardiovascular modulation.

The activation of eNOS is regulated by several post-translational modifications. In quiescent cells, eNOS is present in lipid rafts that are enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids. Lipid rafts have distinct membrane phases with low membrane fluidity and modulate protein–protein and protein–lipid interactions for cellular signal transduction [71]. Lipid rafts include a significant number of receptors, such as G protein-coupled receptors, growth factor receptors and calcium-regulatory proteins. The localization of eNOS in lipid rafts may facilitate the communication between eNOS and activators. Myristylation and palmitoylation of eNOS enhance its affinity toward the lipid raft, and these acylations decrease NO production [67]. Furthermore, the state of lipid rafts can affect downstream signaling cascades, such as the MAPK pathway [71–76]. Abnormalities in sphingolipid composition in senescent ECs leads to insulin resistance [77]. Because these signaling pathways modulate eNOS function, lipid rafts may be involved in eNOS activation in a multi-step process.

The intracellular Ca++ levels are important for eNOS activation because eNOS requires calmodulin binding to exert maximal enzymatic activity. Calmodulin is a target of intracellular Ca++, which changes its conformation in response to the respective adduct proteins. When eNOS binds to calmodulin, it facilitates the transfer of electrons from NADPH to the oxygenase domain for L-arginine catalyzation [78]. Binding of calmodulin simultaneously inhibits the interaction between lipid rafts and eNOS during the activation process. In addition, phosphorylation and de-phosphorylation of eNOS are critical steps, together with acylation and calmodulin binding. Phosphorylation of Ser 1177 is a key activation locus, which enhances the binding of calmodulin as well as the internal electron flux of eNOS. In contrast, phosphorylation of Thr 495 attenuates the binding of calmodulin, causing eNOS inactivation. Thus, the phosphorylation of Ser 1177 and the dephosphorylation of Thr 495 are eNOS activation-specific markers.

The Akt pathway-dependent eNOS levels were elevated in irradiated ECs in tumors, leading to an acceleration in NO release and associated increase in tumor blood flow demonstrating that radiation induces activation of eNOS [79]. In addition to IR, ultraviolet radiation was shown to augment CHK2 phosphorylation, leading to eNOS activation in bovine aortic ECs (bovine aortic ECs; BAECs) [74, 80] and involvement of PKC-βII [81] and the MAPK pathway in NO production in human vascular ECs and human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs), respectively [82]. These protein kinases, involved in eNOS activation, are important signaling mediators of the DDR, downstream of ATM kinase. We have previously demonstrated the role of ATM, a key regulator of the DDR, in eNOS activation in ECs [56, 83]. Subsequently, we reported the involvement of ATM in eNOS Ser 1177 phosphorylation [83]. We showed that glutamate is present sequentially after Ser 1177 of eNOS (Human: 1171- srirtQSfsl −1180, Cow: 1171- vtsrirtQSf -1180, Mouse: 1171- rirtQSfslq -1180), which is recognized and phosphorylated by ATM. Consistently, an ATM inhibitor markedly decreased the eNOS Ser 1179 phosphorylation [56]. ATM is originally localized in the nucleolus to sense DNA damage; several studies have shown that cytoplasmic-activated ATM translocates to the cytoplasm to upregulate NF-κB [84], mTORC1 [85] and p38 MAPK [86]. Thus, ATM may phosphorylate eNOS both directly and indirectly. Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) is a well-conserved, highly expressed molecular chaperone protein that assists in protein folding and stabilization [87]. The chaperone HSP90 is involved in several steps of DDR and has been shown to stabilize the trimeric MRN protein complex containing Mre11, Rad50 and Nbs1. To process homologous recombination, MRN complex recruits ATM to DNA lesions [88, 89]. We previously found that inhibition of HSP90 disrupted ATM activity and eNOS activation post-IR [83]. As most of the eNOS is expressed in vascular ECs, ATM-dependent eNOS upregulation is likely to be EC-specific, eliciting a unique DDR in ECs after radiation exposure.

Interestingly, several studies have shown that radiation exposure enhances eNOS Ser 1179 phosphorylation as well as eNOS gene/protein expression [56, 79]. It is well known that the DDR activates several transcriptional factors, such as p53, Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), and AP-1/2 [47]. The promoter region of the eNOS gene has been cloned from ECs of several species, and there is a high degree of promoter sequence homology among the different species [67]. Similar to many so-called constitutively expressed proteins, the eNOS promoter lacks a typical TATA box; however, there are multiple potential regulatory DNA sequences, including a CCAT box, Sp1 sites, GATA motifs, CACCC boxes, AP-1 site, a p53-binding region and sterol-regulatory elements. Furthermore, it was reported that inhibition of ATM or JNK decreased the radiation-induced eNOS gene expression and NO production. Stress-activated kinase JNK is a highly conserved serine/threonine kinase involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, motility, apoptosis and survival that co-ordinates with other MAPKs [55]. JNK phosphorylates c-Jun, which binds to c-FOS to form AP-1. The promoter region of eNOS has a transcription binding site for AP-1 as the MAPK-regulating transcription factor. Thus, these studies established that DDR induces the expression and phosphorylation of eNOS to produce NO in ECs after IR.

Radiation-induced eNOS activation induces senescence of vascular ECs

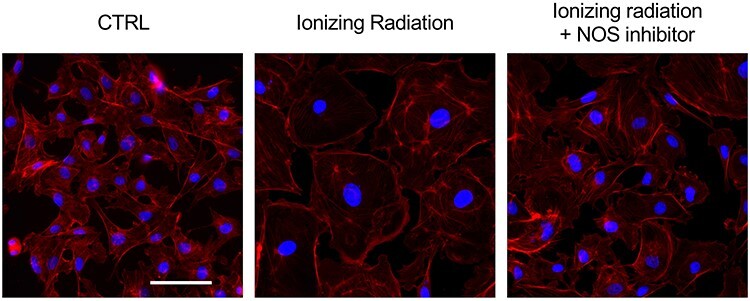

NO release by eNOS in ECs exerts beneficial effects for the most part, but it may also cause adverse effects in the cells, such as DNA damage and subsequent mutagenesis [90]. However, several studies have shown that NO may play a role in preventing cell death [28, 91, 92]. As shown in Fig. 3, X-irradiation induced a senescence-like phenotype in BAECs, which was mitigated by a general NOS inhibitor (N-Nitro-L-arginine methylester; L-NAME). L-NAME modifies the guanidino group of L-arginine and inhibits NO production by blocking the binding of NOS to its substrate, L-arginine. Corroborating these results, IR augmented the senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity, and L-NAME treatment diminished the effect [56]. Cell-cycle arrest is employed by cells to repair DNA damage before cell proliferation. Although cell-cycle analysis showed G0/G1 arrest after irradiation, NOS inhibition attenuated this G0/G1 arrest in BAECs post-IR. Moreover, these data indicated that NO activated by DDR regulates the fate of ECs after radiation exposure.

Fig. 3.

Senescence in bovine aortic ECs by eNOS activation after radiation exposure. BAECs were irradiated at 4 Gy and incubated for 48 h. Cells were stained with phalloidin-A549 and their morphology was visualized. Irradiated cells showed senescent-like phenotype, and NO inhibitor L-NAME prevents senescence after radiation exposure. Blue; DAPI, Red; phalloidin-A594, Black bar = 20 μm. Abbreviations: ECs, endothelial cells; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide.

Cellular senescence plays a distinct role in chronic diseases [65, 93]. EC senescence is involved not only in CVD but also in the progression of Alzheimer’s neuropathology [66]. In the molecular mechanisms of NO-mediated senescence, reactive nitrogen species (RNS) may be involved in the pathology of CVD following IR. RNS are a family of antimicrobial molecules derived from peroxynitrite (ONOO−), NO, and superoxide, which work in conjunction with ROS [90]. RNS can modify proteins by the nitration of cysteine (S-nitrosylation) and tyrosine (3-Nitrotyrosine), and nitrated proteins lose their ability to maintain bio-systems [90, 94]. Although RNS functions in several organs along with ROS, relatively few studies have demonstrated its involvement in NO production and endothelial dysfunction. Further studies are needed to understand the role of radiation-induced NO in the mechanism of senescence to understand its pathological effects on the cardiovascular system.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVES

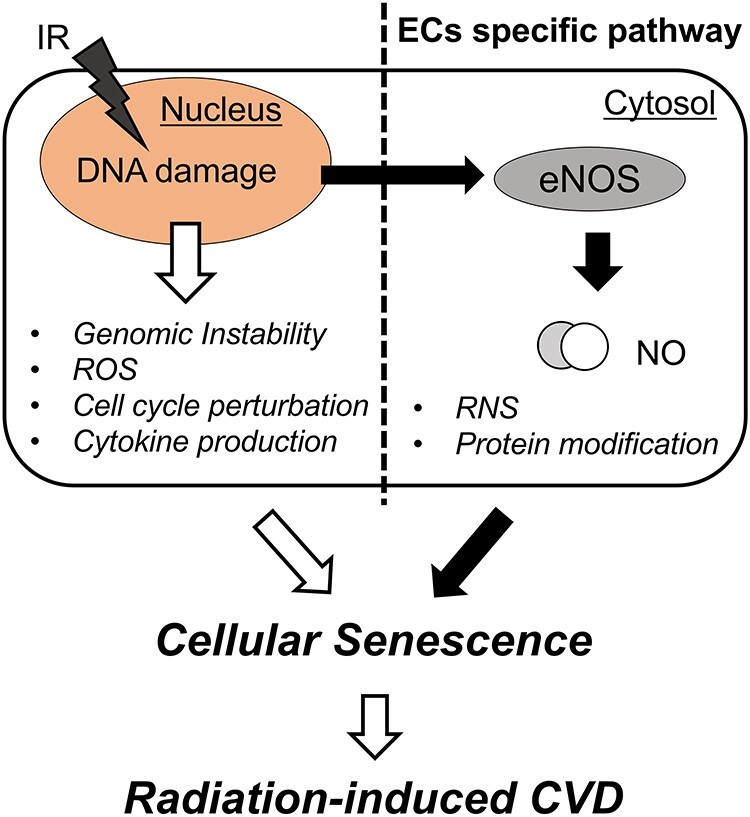

The technological developments in radiation therapy facilitate high-dose radiotherapy. However, some portion of the radiation attacks healthy tissues. Along with its tumoricidal action, avoiding radiation-induced side effects is an important factor in radiation therapy. Since radiation-induced CVD is a lethal side effect, preventing it is crucial for effective radiotherapy. This article provides insights into EC physiology and their role in the pathological development of age- and radiation-related CVD. Because senescent ECs were difficult to remove and release pro-inflammatory cytokines [34], senescent ECs play an important role in inducing CVD after radiation exposure. DDR plays a significant role in the cellular response to IR and is involved in radiation-induced eNOS activation. DDR in irradiated ECs includes the hyper-production of NO, resulting from molecular mechanisms caused by radiation-induced eNOS activation. The phosphorylation of eNOS-Ser1179 and the activation of eNOS post-irradiation are modulated by the master regulators of DDR, ATM and ATR kinases. Considering that eNOS is more likely to be expressed in vascular ECs than in other tissues, NO production induced by the DDR is one of the unique signaling mechanisms in the body (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

DDR in endothelial cells. Conventional DDR (left side) induces various cellular response as listed, and NO production may generate an endothelial-specific response toward ionizing radiation in the cardiovascular system (right side). Abbreviations: NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Although radiation-induced CVD is a fatal side effect of radiation therapy, the radio-response of ECs to IR has not been investigated so far, especially at low doses [20]. This is an important issue in outer space research/development and medical exposure. In space, exposure to cosmic rays during the round trip between Mars and Earth is believed to be equivalent to approximately 0.7 Gy radiation exposure [2]. The risk of carcinogenesis in the same dose range is 5%, while the risk of CVD increases by 10–13% [5]. Therefore, this issue is important not only for radiation treatment but also for space development. Thus, elucidation of the molecular pathology of radiation-induced CVD is essential for medical purposes as well as for mitigating the risk of CVD in outer space activity.

It is well elucidated that DDR plays an important role in the determination of cellular fate after radiation exposure. In this article, we summarize the pathology of age-related and radiation-induced CVD. We also describe the role of eNOS and NO in the senescence of ECs following radiation exposure. Enhanced NO production in patients receiving radiation treatment may heighten the risk of injury to normal tissues in the cardiovascular system. Further study is warranted to elucidate the role of radiation-induced NO in the mechanism of radiation-induced senescence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Chiaki Niwa (Laboratory of Biochemistry, Azabu University) for figure illustration and Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number JP19K20452 and 20KK0250 (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Matsumoto H, Takahashi A, Ohnishi T. Radiation-induced adaptive responses and bystander effects. Biol Sci Space 2004;18:247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell 2010;40:179–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennetzen MV, Larsen DH, Bunkenborg J et al. Site-specific phosphorylation dynamics of the nuclear proteome during the DNA damage response. Mol Cell Proteomics 2010;9:1314–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bensimon A, Schmidt A, Ziv Y et al. ATM-dependent and -independent dynamics of the nuclear phosphoproteome after DNA damage. Sci Signal 2010;3:rs3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shimizu Y, Kodama K, Nishi N et al. Radiation exposure and circulatory disease risk: Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivor data, 1950–2003. BMJ 2010;340:b5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hauptmann M, Mohan AK, Doody MM et al. Mortality from diseases of the circulatory system in radiologic technologists in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:239–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Howe GR, Zablotska LB, Fix JJ et al. Analysis of the mortality experience amongst U.S. nuclear power industry workers after chronic low-dose exposure to ionizing radiation. Radiat Res 2004;162:517–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ivanov VK. Late cancer and noncancer risks among Chernobyl emergency workers of Russia. Health Phys 2007;93:470–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Darby SC, Ewertz M, McGale P et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:987–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Darby SC, McGale P, Taylor CW et al. Long-term mortality from heart disease and lung cancer after radiotherapy for early breast cancer: prospective cohort study of about 300,000 women in US SEER cancer registries. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:557–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ryu WI, Lee H, Bae HC et al. IL-33 down-regulates CLDN1 expression through the ERK/STAT3 pathway in keratinocytes. J Dermatol Sci 2018;90:313–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Szpakowski N, Desai MY. Radiation-associated pericardial disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2019;21:97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adams MJ, Lipsitz SR, Colan SD et al. Cardiovascular status in long-term survivors of Hodgkin's disease treated with chest radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3139–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bowers DC, McNeil DE, Liu Y et al. Stroke as a late treatment effect of Hodgkin's disease: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:6508–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Bruin ML, Dorresteijn LD, van't Veer MB et al. Increased risk of stroke and transient ischemic attack in 5-year survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:928–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xue J, Han C, Jackson A et al. Doses of radiation to the pericardium, instead of heart, are significant for survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol 2019;133:213–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Darby S, McGale P, Peto R et al. Mortality from cardiovascular disease more than 10 years after radiotherapy for breast cancer: nationwide cohort study of 90 000 Swedish women. BMJ 2003;326:256–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McGale P, Darby SC, Hall P et al. Incidence of heart disease in 35,000 women treated with radiotherapy for breast cancer in Denmark and Sweden. Radiother Oncol 2011;100:167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative, G, Darby S, McGale P et al. Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet 2011;378:1707–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stewart FA. Mechanisms and dose-response relationships for radiation-induced cardiovascular disease. Ann ICRP 2012;41:72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stewart FA, Seemann I, Hoving S et al. Understanding radiation-induced cardiovascular damage and strategies for intervention. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2013;25:617–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aleman BM, van den Belt-Dusebout AW, De Bruin ML et al. Late cardiotoxicity after treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2007;109:1878–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Niska JR, Thorpe CS, Allen SM et al. Radiation and the heart: systematic review of dosimetry and cardiac endpoints. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2018;16:931–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pan L, Lei D, Wang W et al. Heart dose linked with cardiac events and overall survival in lung cancer radiotherapy: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e21964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Andratschke N, Maurer J, Molls M et al. Late radiation-induced heart disease after radiotherapy. Clinical importance, radiobiological mechanisms and strategies of prevention. Radiother Oncol 2011;100:160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kruger-Genge A, Blocki A, Franke RP et al. Vascular endothelial cell biology: an update. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:4411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sturtzel C. Endothelial cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017;1003:71–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Farah C, Michel LYM, Balligand JL. Nitric oxide signalling in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2018;15:292–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Donato AJ, Morgan RG, Walker AE et al. Cellular and molecular biology of aging endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015;89:122–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Muz B, de la Puente P, Azab F et al. The role of hypoxia in cancer progression, angiogenesis, metastasis, and resistance to therapy. Hypoxia (Auckl) 2015;3:83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Soufi M, Sattler AM, Herzum M et al. Molecular basis of obesity and the risk for cardiovascular disease. Herz 2006;31:200–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Childs BG, Li H, van Deursen JM. Senescent cells: a therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest 2018;128:1217–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kennedy BK, Berger SL, Brunet A et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell 2014;159:709–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jia G, Aroor AR, Jia C et al. Endothelial cell senescence in aging-related vascular dysfunction. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2019;1865:1802–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Senoner T, Dichtl W. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases: still a therapeutic target? Nutrients 2019;11:2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Herranz N, Gil J. Mechanisms and functions of cellular senescence. J Clin Invest 2018;128:1238–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Suzuki M, Boothman DA. Stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS)—influence of SIPS on radiotherapy. J Radiat Res 2008;49:105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Molavi B, Mehta JL. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular disease: molecular basis of its deleterious effects, its detection, and therapeutic considerations. Curr Opin Cardiol 2004;19:488–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hall EJ, Giaccia AJ. Radiobiology for the Radiologist. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen K, Thomas SR, Keaney JF Jr. Beyond LDL oxidation: ROS in vascular signal transduction. Free Radic Biol Med 2003;35:117–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dasika GK, Lin SC, Zhao S et al. DNA damage-induced cell cycle checkpoints and DNA strand break repair in development and tumorigenesis. Oncogene 1999;18:7883–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tubbs A, Nussenzweig A. Endogenous DNA damage as a source of genomic instability in cancer. Cell 2017;168:644–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sakai Y, Yamamori T, Yoshikawa Y et al. NADPH oxidase 4 mediates ROS production in radiation-induced senescent cells and promotes migration of inflammatory cells. Free Radic Res 2018;52:92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Toussaint O, Medrano EE, von Zglinicki T. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS) of human diploid fibroblasts and melanocytes. Exp Gerontol 2000;35:927–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Oh, Bump EA, Kim JS et al. Induction of a senescence-like phenotype in bovine aortic endothelial cells by ionizing radiation. Radiat Res 2001;156:232–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim ST, Lim DS, Canman CE et al. Substrate specificities and identification of putative substrates of ATM kinase family members. J Biol Chem 1999;274:37538–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bensimon A, Aebersold R, Shiloh Y. Beyond ATM: the protein kinase landscape of the DNA damage response. FEBS Lett 2011;585:1625–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Di Leonardo A, Linke SP, Clarkin K et al. DNA damage triggers a prolonged p53-dependent G1 arrest and long-term induction of Cip1 in normal human fibroblasts. Genes Dev 1994;8:2540–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ho YS, Wang YJ, Lin JK. Induction of p53 and p21/WAF1/CIP1 expression by nitric oxide and their association with apoptosis in human cancer cells. Mol Carcinog 1996;16:20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moiseeva O, Mallette FA, Mukhopadhyay UK et al. DNA damage signaling and p53-dependent senescence after prolonged beta-interferon stimulation. Mol Biol Cell 2006;17:1583–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dent P, Yacoub A, Fisher PB et al. MAPK pathways in radiation responses. Oncogene 2003;22:5885–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wu CE, Koay TS, Esfandiari A et al. ATM dependent DUSP6 modulation of p53 involved in synergistic targeting of MAPK and p53 pathways with Trametinib and MDM2 inhibitors in cutaneous melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2018;11:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pak BJ, Lee J, Thai BL et al. Radiation resistance of human melanoma analysed by retroviral insertional mutagenesis reveals a possible role for dopachrome tautomerase. Oncogene 2004;23:30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Khalil A, Morgan RN, Adams BR et al. ATM-dependent ERK signaling via AKT in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell Cycle 2011;10:481–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang Z, Wang M, Kar S et al. Involvement of ATM-mediated Chk1/2 and JNK kinase signaling activation in HKH40A-induced cell growth inhibition. J Cell Physiol 2009;221:213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nagane M, Kuppusamy ML, An J et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase regulates eNOS expression and modulates Radiosensitivity in endothelial cells exposed to ionizing radiation. Radiat Res 2018;189:519–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kim J, Wong PK. Loss of ATM impairs proliferation of neural stem cells through oxidative stress-mediated p38 MAPK signaling. Stem Cells 2009;27:1987–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Xie H, Li C, Dang Q et al. Infiltrating mast cells increase prostate cancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy resistances via modulation of p38/p53/p21 and ATM signals. Oncotarget 2016;7:1341–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Igarashi K, Sakimoto I, Kataoka K et al. Radiation-induced senescence-like phenotype in proliferating and plateau-phase vascular endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res 2007;313:3326–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Igarashi K, Miura M. Inhibition of a radiation-induced senescence-like phenotype: a possible mechanism for potentially lethal damage repair in vascular endothelial cells. Radiat Res 2008;170:534–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang Y, Boerma M, Zhou D. Ionizing radiation-induced endothelial cell senescence and cardiovascular diseases. Radiat Res 2016;186:153–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Day RM, Snow AL, Panganiban RA. Radiation-induced accelerated senescence: a fate worse than death? Cell Cycle 2014;13:2011–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schaue D, Kachikwu EL, McBride WH. Cytokines in radiobiological responses: a review. Radiat Res 2012;178:505–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Krombach J, Hennel R, Brix N et al. Priming anti-tumor immunity by radiotherapy: dying tumor cell-derived DAMPs trigger endothelial cell activation and recruitment of myeloid cells. Oncoimmunology 2019;8:e1523097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Basisty N, Kale A, Jeon OH et al. A proteomic atlas of senescence-associated secretomes for aging biomarker development. PLoS Biol 2020;18:e3000599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Garwood CJ, Simpson JE, Al Mashhadi S et al. DNA damage response and senescence in endothelial cells of human cerebral cortex and relation to Alzheimer's neuropathology progression: a population-based study in the Medical Research Council cognitive function and ageing study (MRC-CFAS) cohort. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2014;40:802–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Förstermann U, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. Eur Heart J 2012;33:829–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim SO et al. Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005;6:150–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Stomberski CT, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Protein S-Nitrosylation: determinants of specificity and enzymatic regulation of S-Nitrosothiol-based signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 2019;30:1331–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhang Y, Deng Y, Yang X et al. The relationship between protein S-Nitrosylation and human diseases: a review. Neurochem Res 2020;45:2815–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Simons K, Toomre D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2000;1:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yamashita T, Hashiramoto A, Haluzik M et al. Enhanced insulin sensitivity in mice lacking ganglioside GM3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:3445–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Shimizu T, Nagane M, Suzuki M et al. Tumor hypoxia regulates ganglioside GM3 synthase, which contributes to oxidative stress resistance in malignant melanoma. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2020;1864:129723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hakomori S. Glycosphingolipids in cellular interaction, differentiation, and oncogenesis. Annu Rev Biochem 1981;50:733–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kawashima N, Nishimiya Y, Takahata S et al. Induction of glycosphingolipid GM3 expression by valproic acid suppresses cancer cell growth. J Biol Chem 2016;291:21424–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Schnaar RL. The biology of gangliosides. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem 2019;76:113–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sasaki N, Itakura Y, Toyoda M. Ganglioside GM1 contributes to the state of insulin resistance in senescent human arterial endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2015;290:25475–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rafikov R, Fonseca FV, Kumar S et al. eNOS activation and NO function: structural motifs responsible for the posttranslational control of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. J Endocrinol 2011;210:271–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sonveaux P, Brouet A, Havaux X et al. Irradiation-induced angiogenesis through the up-regulation of the nitric oxide pathway: implications for tumor radiotherapy. Cancer Res 2003;63:1012–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Park JH, Kim WS, Kim JY et al. Chk1 and Hsp90 cooperatively regulate phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase at serine 1179. Free Radic Biol Med 2011;51:2217–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Sakata K, Kondo T, Mizuno N et al. Roles of ROS and PKC-betaII in ionizing radiation-induced eNOS activation in human vascular endothelial cells. Vascul Pharmacol 2015;70:55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wang H, Segaran RC, Chan LY et al. Gamma radiation-induced disruption of cellular junctions in HUVECs is mediated through affecting MAPK/NF-kappaB inflammatory pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019;1486232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nagane M, Yasui H, Sakai Y et al. Activation of eNOS in endothelial cells exposed to ionizing radiation involves components of the DNA damage response pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015;456:541–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hinz M, Stilmann M, Arslan S et al. A cytoplasmic ATM-TRAF6-cIAP1 module links nuclear DNA damage signaling to ubiquitin-mediated NF-κB activation. Mol Cell 2010;40:63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Alexander A, Cai SL, Kim J et al. ATM signals to TSC2 in the cytoplasm to regulate mTORC1 in response to ROS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:4153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Yang Y, Xia F, Hermance N et al. A cytosolic ATM/NEMO/RIP1 complex recruits TAK1 to mediate the NF-kappaB and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/MAPK-activated protein 2 responses to DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol 2011;31:2774–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Whitesell L, Lindquist SL. HSP90 and the chaperoning of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5:761–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Uziel T, Lerenthal Y, Moyal L et al. Requirement of the MRN complex for ATM activation by DNA damage. EMBO J 2003;22:5612–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Pennisi R, Ascenzi P, di Masi A. Hsp90: a new player in DNA repair? Biomolecules 2015;5:2589–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Afanas'ev I. ROS and RNS signaling in heart disorders: could antioxidant treatment be successful? Oxid Med Cell Longev 2011;293769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Nitric oxide and apoptosis: another paradigm for the double-edged role of nitric oxide, Nitric. 1997;1:275–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Nicotera P, Brune B, Bagetta G. Nitric oxide: inducer or suppressor of apoptosis? Trends Pharmacol Sci 1997;18:189–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Shimizu I, Minamino T. Cellular senescence in cardiac diseases. J Cardiol 2019;74:313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Tuteja N, Chandra M, Tuteja R et al. Nitric oxide as a unique bioactive signaling messenger in physiology and pathophysiology. J Biomed Biotechnol 2004;227–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]