Abstract

Background:

Various factors, such as age, cardiovascular concerns, and lifestyle patterns, are associated with risk for cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Risk scores model predictive risk of developing a disease (e.g., dementia, stroke). Many of these scores have been primarily developed in largely non-Hispanic/Latino (non-H/L) White samples and little is known about their applicability in ethno-racially diverse populations.

Objective:

The primary aim was to examine the relationship between three established risk scores and cognitive performance. These relationships were compared across ethnic groups.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study with a multi-ethnic, rural-dwelling group of participants (Mage = 61.6 ± 12.6 years, range: 40–96 years; 373F:168M; 39.7% H/L). The Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging and Dementia (CAIDE), Framingham Risk Score (FRS), and Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP) score were calculated for each participant.

Results:

All three scores were significantly associated with cognition in both H/L and non-H/L groups. In H/Ls, cognition was predicted by FRS: β = −0.08, p = 0.022; CAIDE: β = −0.08, p < 0.001; and WHICAP: β = −0.04, p < 0.001. In non-H/Ls, cognition was predicted by FRS: β = −0.11, p < 0.001; CAIDE: β = −0.14, p < 0.001; and WHICAP: β = −0.08, p < 0.001. The strength of this relationship differed between groups for FRS [t(246) = −4.61, p < 0.001] and CAIDE [t(420) = −3.20, p = 0.001], but not for WHICAP [t(384) = −1.03, p = 0.30], which already includes ethnicity in its calculation.

Conclusion:

These findings support the utility of these three risk scores in predicting cognition while underscoring the need to account for ethnicity. Moreover, our results highlight the importance of cardiovascular and other demographic factors in predicting cognitive outcomes.

Keywords: Aging, cognition, dementia, Hispanic Americans, minority health

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause for dementia and the number of people affected with this disease is rapidly rising [1]. AD is clinically expressed by cognitive and functional impairment and biologically characterized by an increase in amyloid-β plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, which are associated with evidence of neurodegeneration [2]. While these biomarkers are commonly seen in asymptomatic aging brains, people with AD tend to have greater accumulation of these plaques and tangles [3, 4]. Signs and symptoms of this disease can include subtle personality changes in the early stages of the disease, memory loss, language impairment, deficits in logical reasoning and problem-solving, and an inability to carry out daily routines [3]. Significant progress has been made in understanding the neurobiological underpinnings of dementia and AD, but little progress has been made in generating clear causal models that explain risks for cognitive decline and dementia [5].

In terms of risk, age is the largest biological risk factor for developing AD [6]. However, other risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing AD have been identified and include: deteriorating brain health (e.g., history of strokes), cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., high blood pressure), diabetes, illiteracy, low educational attainment and/or lower cognitive reserve, and ethno-racial background [7–9]. Additionally, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele is considered a genetic risk factor for the disease, though it has been found that risk conveyed by the APOE ε4 allele is lower in H/Ls than in White non-H/Ls; this suggests that APOE genetic risk variants may not carry the same degree of risk in H/Ls and instead other risk factors may contribute to the added risk of AD in diverse individuals [10–12].

Compared to older Whites/European Americans, Hispanics/Latinos (H/L) are at about 50% greater risk of developing AD and have a higher prevalence of cognitive impairment, though not all studies find this to be true [13, 14]. One possible explanation for this potential greater risk may be a higher prevalence of health conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) in H/Ls. Across numerous studies, it has been demonstrated that H/Ls have lower mortality rates across multiple disease domains and live longer than Whites/European Americans, which may contribute to a greater lifetime risk for AD [15]. Despite the increased risk, there is evidence that older H/Ls have a higher rate of undiagnosed AD than non-Hispanic White/European American adults [16]. It has been noted that limitations in access to healthcare, cultural perspectives and misconceptions about “normal” aging, AD, and its course could be contributing to the underdiagnosis of AD in L/Hs [13]. In light of these health disparities and the implications of early diagnosis on early intervention, it is critical to develop methods for identifying high-risk populations.

Risk scores (RSs) are one method for predicting an individual’s chances of developing a disease in the future, such as stroke or dementia. These scores can be calculated using risk factors based on the person’s history of illnesses and lifestyle patterns. One possible benefit of RSs is that they can be used in the context of prevention, particularly in diseases that have cures or treatments [17]. While AD does not currently have a cure, this method of prediction may help reduce risk or delay onset of symptoms by addressing modifiable risk factors (e.g., hypertension) that could possibly help prevent further complications. It is important to consider that RSs are a means of estimateing risk and must not be viewed as a definite diagnosis [17]. In terms of AD, RSs can be used to account for various factors known to be associated with an increased risk for dementia; these include, but are not limited to, a combination of demographic, health, and lifestyle-related components: age, gender, heart disease, history of stroke, diabetes, smoking, race, and socioeconomic status. While RSs have been primarily studied in non-Hispanic White/European American populations, limited research has suggested possible use in other ethno-racial groups; however, evidence suggests they may tend to under/overestimate risk in minority groups, such as H/Ls or Blacks/African Americans [18].

Here we examine the following risk scores: The Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Dementia (CAIDE) risk score, the Framingham Risk Score (FRS), and the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP) score. The CAIDE risk score was developed to predict one’s likelihood of developing dementia based on vascular risk factors present at midlife in a sample of participants from eastern Finland [19]. The developers of CAIDE selected scores of ≥ 10 as the cutoff, which had a sensitivity of 0.81 and a specificity of 0.61. A score of ≥9 was used as the cut-off for CAIDE-without APOE and had a sensitivity of 0.77 and a specificity of 0.63.

FRS was developed to predict one’s likelihood of having a cardiovascular event using sex-specific multivariable functions that included several vascular risk factors (e.g., age, treatment for hypertension). This risk score was developed using data from the original Framingham Heart Study and the Framingham Offspring Study, which consisted of 100% European-American participants [20]. FRS’ sensitivity of the top sex-specific quintiles of predicted risk in men was 47% in men and 56% in women, while specificity was 85% in men and 83% in women [21].

Lastly, the WHICAP summary risk score was created to predict AD in older adults based on their vascular profiles [10]. In contrast to both CAIDE and FRS, the study population used for the development of the WHICAP risk score was diverse and roughly equally proportioned in the number of White (34.2%), Black (30.6%), and Hispanic/Latino (33.3%) participants. The developers of the WHICAP risk score reported hazard ratios for each of the risk factors used to calculate the risk score, which ranged from 1.15–18.023. Information on the sensitivity and specificity of the WHICAP risk score have not been reported elsewhere. While RSs have been primarily studied in non-Hispanic White/European-American populations, limited research has suggested possible use in other ethno-racial groups; however, evidence suggests they may tend to under/overestimate risk in minority groups, such as H/Ls or Blacks/African Americans [18].

As noted earlier, compared to non-Hispanic Whites where genetic risk factors may play a significant role, AD risk in H/Ls may be attributed more to lifestyle factors and health issues, such as cardiovascular disease [22], many of which are modifiable [23]. Therefore, RSs may hold promise in predicting these modifiable risk factors early in life in H/Ls, which may then help delay one’s progression to AD-related dementia. Cognitive impairment is a hallmark sign in the development of AD-related dementia and assessing the relationship between cognition and RSs may help further validate the use of RSs in AD. In a previous study comparing cognitive decline and RSs in a British population, researchers found that the RSs of interest (i.e., CAIDE and FRS) predicted cognitive decline in late middle age [24]. Although these risk scores were originally designed to longitudinally predict future health outcomes, several attempts to further validate these scores have been carried out in cross-sectional samples [25–27]. However, these were largely limited in the diversity of their samples. In the current study, we sought to broaden current knowledge of the relationship between RSs and cognition in an ethnically diverse sample.

The primary aim of this study was to examine the relationship between three established RSs (i.e., CAIDE, FRS, and the WHICAP score) and cognition in a diverse sample. The second aim was to compare the relationship between RSs and cognition between H/Ls and non-H/Ls. Our last aim was exploratory in nature and was to examine the relationship between RSs and the five cognitive sub-domains that comprised our cognitive composite from the first two aims: executive functioning, language, attention, visuospatial abilities, and memory. We hypothesized that the three RSs used in this study would not be equally predictive of cognition given the variety in factors included in each RS calculation and the sample of participants used to develop the scores.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

This study utilized a cross-sectional analysis of data collected from Project FRONTIER (Facing Rural Obstacles to Healthcare Now Through Intervention, Education & Research), an epidemiological study of cognitive aging [28]. Study participants were rural-dwelling individuals recruited using a community-based participatory research approach through collaborations with local clinics and hospitals. Participants were also recruited from senior citizen’s organizations. The protocol included a standardized medical examination, clinical labs, neuropsychological testing, and brief individual interviews with the participant and an informant. Inclusion criteria for the larger study required that participants be 40 years of age or older and live in one of the participating counties (i.e., Cochran and Parmer Counties, located west of Lubbock, Texas). Cognitive data were available for a total of 541 participants (68.9% women, Mage = 61.6 years ± 12.6, age range: 40–96 years; 39.7% Hispanic/Latino). The majority (71.9%) of the sample was cognitively normal as determined by the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR) [29] and were of lower SES background. Distributions for age, gender, education, race/ethnicity and other demographics are reported in Table 1; clinical data are reported in Table 2. Project FRONTIER was approved by the University of Northern Texas IRB and all participants signed written informed consent.

Table 1.

Demographics of full sample

| N | 541 | |

| Mean Age in Years (Range) | 61.6 ± 12.6(40–96) | |

| Sex | N | % |

| Female | 373 | 68.9 |

| Male | 168 | 31.1 |

| Mean Education in Years (Range) | 10.9 ± 4.3 (0–20) | |

| Current Household Income | N | % |

| <$10,000 | 85 | 15.7 |

| $10,001 to $20,000 | 146 | 27.0 |

| $20,001 to $30,000 | 82 | 15.2 |

| $30,001 to $40,000 | 50 | 9.2 |

| $40,001 to $50,000 | 50 | 9.2 |

| $50,001 to $60,000 | 22 | 4.1 |

| $60,001 to $70,000 | 27 | 5.0 |

| $70,001 or Higher | 66 | 12.2 |

| Refused to Answer/Don’t Know | 13 | 2.4 |

| Ethnicity/Race | ||

| Hispanic (all races) | 215 | 39.7 |

| Not Hispanic | 285 | 52.7 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 17 | 3.1 |

| Asian | 0 | 0.0 |

| Black/African-American | 23 | 4.3 |

| White or Caucasian | 459 | 84.8 |

| Other | 10 | 1.8 |

| Unknown | 32 | 6.0 |

| Primary Language | ||

| English | 358 | 66.2 |

| Spanish | 182 | 33.6 |

| Bilingual | 214 | 39.6 |

Table 2.

Clinical data of full sample

| N | 541 | |

| Mean Body Mass Index (Range) | 29.6 ± 6.2 (11.8–65.6) | |

| Hypertension | N | % |

| Systolic Blood Pressure ≤ 140 mmHg | 390 | 72.1 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure> 140 mmHg | 130 | 24.0 |

| Cholesterol | ||

| ≤250 mg/dL | 491 | 90.8 |

| >250 mg/dL | 48 | 8.9 |

| Diabetes | ||

| No | 387 | 71.5 |

| Yes | 154 | 28.5 |

| Smoking | ||

| Non-smoker | 261 | 48.2 |

| Past Smoker | 179 | 33.1 |

| Current Smoker | 95 | 17.6 |

| Clinical Dementia Rating Global Score | ||

| Normal (0) | 389 | 71.9 |

| Questionable (0.5) | 149 | 27.5 |

| Mild (1) | 2 | 0.4 |

| Moderate (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Severe (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Cognitive Composite Score (range) | 0.3 ± 0.9 (−3.2 – 2.3) | |

| Risk Scores | ||

| Mean CAIDE (Range) | 7.4 ± 3.1 (0–16) | |

| Mean FRS (Range) | 14.0 ± 4.2 (2–23) | |

| Mean WHICAP (Range) | 18.9 ± 8.7 (1–43) | |

CAIDE, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Incidence of Dementia Risk Score; FRS, Framingham Risk Score; WHICAP, Washington Heights-Inwood Community Aging Project Risk Score.

Procedures

Three different RSs were calculated for the participants and then compared to their cognitive performance on a comprehensive neuropsychological battery.

Cognitive measures

A composite score was calculated using principal components analysis from the raw total scores of the following cognitive measures: an executive clock drawing task (CLOX) [30], the Executive Interview (EXIT) [31], verbal fluency (phonemic with FAS, category with Animals) [32], Trail Making Test – Parts A & B (TMT-A and TMT-B) [33], and the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) [34], which includes sub-tests related to digit span, line orientation, story memory and recall, list learning and recall, picture naming, figure copy, and figure recall. These measures were used to create a composite score that summarized the sample’s cognitive functioning. In our exploratory aim, scores for cognitive sub-domains scores were calculated using principal components analysis from total raw scores. The following cognitive domain scores were calculated: language (RBANS Picture Naming, RBANS Semantic Fluency, and category verbal fluency with Animals), executive functioning (TMT-Part B, EXIT, and phonemic verbal fluency with FAS), visuospatial (RBANS Figure Copy, RBANS Line Orientation, CLOX), attention (RBANS Digit Span, TMT-Part A, and RBANS Coding), and memory (RBANS Figure Recall, RBANS List Recall, and RBANS Story Recall).

Risk scores

For assessment of health risk, the following scores were used: CAIDE [35], FRS [36], and WHICAP [10]. Additional information on the calculation of each of the risk scores can be found in the Supplementary Material.

CAIDE calculation.

The CAIDE risk score was developed as a predictor of one’s risk of having dementia within the next 20 years and accounts for the following risk factors: age, gender, education, systolic blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), total cholesterol, physical activity, and presence of APOE ε4 allele [19, 35]. The CAIDE score has two different versions available, one with APOE included (CAIDE) and the other without (CAIDE without APOE). Given the data available, we examined participants using both versions. The final CAIDE risk score (with APOE) is calculated as a sum of the points received from the eight risk factors [19]. Of the full sample, the variables necessary to calculate CAIDE were available for 476 participants.

FRS calculation.

The FRS was created using data from the Framingham Heart Study [37] and can be used to estimate one’s risk of developing cardiovascular disease (e.g., coronary heart disease) in the next 10 years. The aim of the FRS is to assess cumulative risk and estimate the likelihood one would develop coronary heart disease by assigning different weights to known cardiovascular risk factors [36]. Low risk is defined as <10% CVD risk, intermediate risk is 10–20%, and high risk is >20% CVD risk within the next decade [38]. Calculation of the FRS considers the following risk factors: age, gender, current smoking status, total cholesterol (mg/dL), high-density lipoproteins (HDL) (mg/dL), systolic blood pressure, and use of blood pressure medications. Each participant is assigned a score based on each categorical risk factor and its level of risk by gender [36]. The total score is calculated as a sum of the points from the five risk factors. Of the full sample, the variables necessary to calculate FRS were available for 283 participants.

WHICAP calculation.

The WHICAP score is a formula to estimate one’s late-life risk of developing dementia based on vascular risk factors associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). Like CAIDE, the WHICAP score has two different versions available (i.e., “Probable and Possible LOAD” and the “Probable LOAD”). We examined participants using the Probable and Possible LOAD scores, which range from 0 to 60 possible points. The risk factors considered include sex, age, presence of diabetes and/or hypertension, current smoking status, low HDL, waist-to-hip ratio, education, ethnicity, and APOE ε4 allele status. The risk score is calculated as a sum of the points from each risk factor [10]. In the current study, waist-to-hip ratio was not available; therefore, a similar variable, BMI, was used instead such that individuals with a BMI greater than 25 were considered “high BMI.” All other variables were the same as originally used in the WHICAP score. Of the full sample, the variables necessary to calculate WHICAP were available for 437 participants.

Analyses

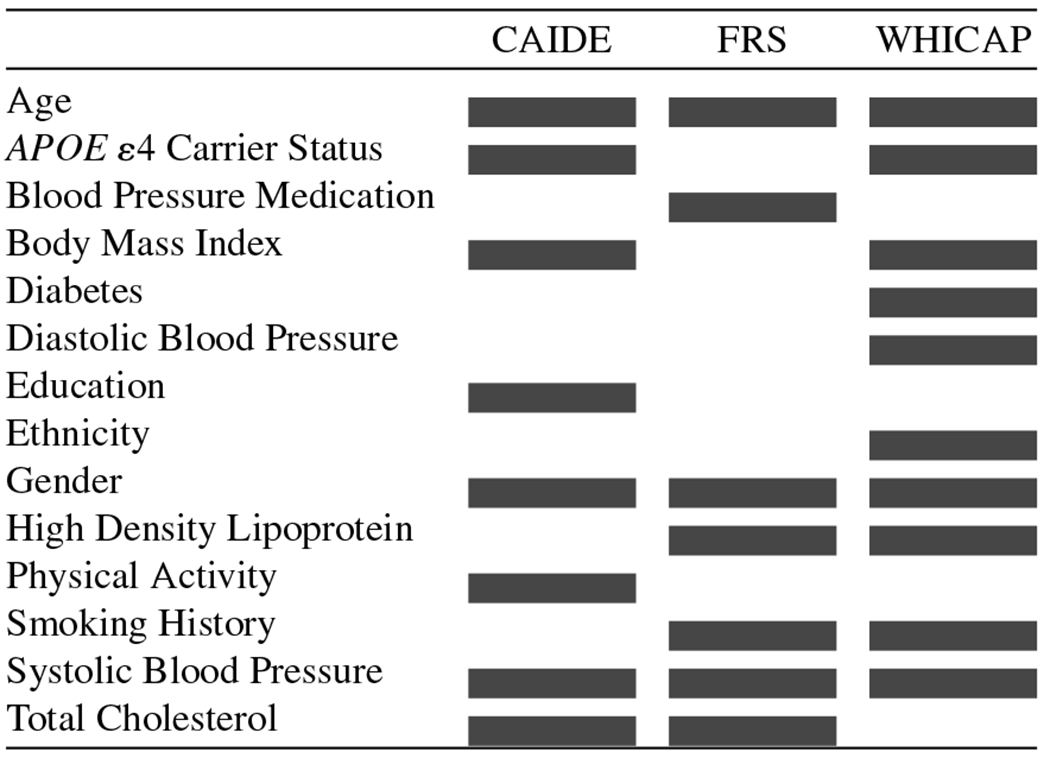

All RSs were calculated and their relationships with cognition analyzed using general linear modeling in SPSS version 25 [39]. The risk factors used to calculate each score are summarized in Table 3, which also demonstrates notable overlap between CAIDE and WHICAP given their emphasis on vascular risk.

Table 3.

Variables included in each RS Calculation

|

CAIDE, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Incidence of Dementia Risk Score; FRS, Framingham Risk Score; WHICAP, Washington Heights-Inwood Community Aging Project Risk Score.

We first tested the cognitive composite as the outcome of the individual risk scores as predictors using linear regression. We then examined the predictive relationship between individual risk scores and ethnicity as predictors of the cognitive composite score. Lastly, we tested each cognitive domain as the outcome of each individual risk score (e.g., FRS predicting executive functioning).

RESULTS

T-tests revealed statistically significant differences between the ethnic groups across their scores. Compared to non-Hispanics, Hispanics/Latinos had higher mean scores for CAIDE and WHICAP and lower FRS scores and cognitive score than non-H/Ls (all ps < 0.001; Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean, standard deviation (SD), range, significance (p) values between Hispanics and Non-Hispanics in cognition and three risk scores

| Hispanic/Latino | Non-Hispanic/Latino | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | ||

| Cognition (H/L: n = 215; non-H/L: n = 285) | −0.25 (0.86) | −2.56 – 4.12 | 0.24 (0.94) | −3.16 – 2.29 | <0.001 |

| CAIDE (H/L: n = 205; non-H/L: n = 269) | 8.25 (3.67) | 0–16 | 6.76 (2.40) | 0–14 | <0.001 |

| CAIDE without APOE (H/L: n = 205; non-H/L: n = 269) | 7.80 (3.54) | 0–15 | 6.29 (2.31) | 0–14 | <0.001 |

| FRS (H/L: n = 120; non-H/L: n = 160) | 12.73 (4.10) | 2–22 | 14.85 (4.01) | 3–23 | <0.001 |

| WHICAP (H/L: n = 182; non-H/L: 253) | 24.02 (7.56) | 10–43 | 15.13 (7.57) | 1–42 | <0.001 |

| WHICAP without Race/Ethnicity (H/L: n = 182; non-H/L: 253) | 19.98 (7.59) | 6–33 | 14.87 (7.37) | 1–42 | <0.001 |

CAIDE, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Incidence of Dementia Risk Score; FRS, Framingham Risk Score; WHICAP, Washington Heights-Inwood Community Aging Project Risk Score.

For our first aim, we examined the linear relationship between cognition and each risk score. Results indicated that all three RSs significantly predicted cognition, but the strength of these relationships differed (Fig. 1): CAIDE [R2 = 0.17, F(1,474) = 98.92, p < 0.001], FRS [R2 = 0.11, F(1,281) = 35.16, p < 0.001], and WHICAP [R2 = 0.34, F(1,435) = 220.14, p < 0.001]. The CAIDE risk score was re-calculated without APOE in the formula and was noted to still be significantly related to cognition [R2 = 0.19, F(1,474) = 108.98, p < 0.001]. The WHICAP score was re-run without race/ethnicity as a risk factor. Results indicated that without accounting for ethnicity in its calculation the WHICAP risk score continued to significantly predict cognition [R2 = 0.31, F(1,435) = 193.72, p < 0.001]. Notably, the WHICAP score had the largest effect size both with and without accounting for ethno-racial background.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between cognition and each risk score (mean-standardized) for all the participants.

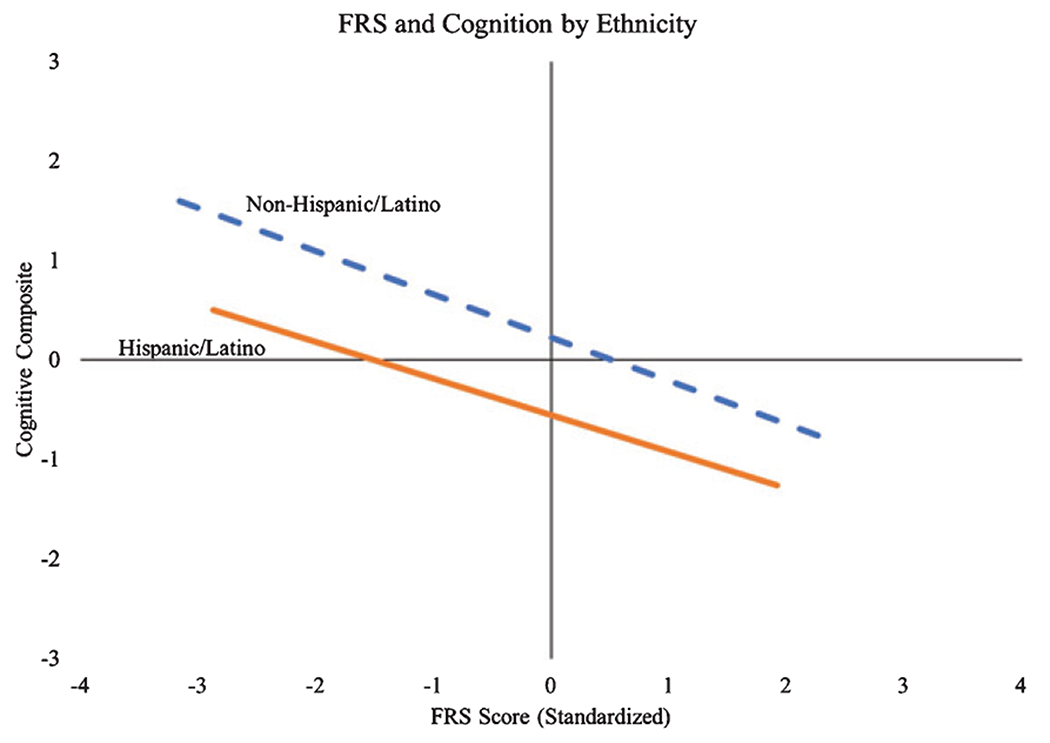

In Aim 2, we examined the role of ethnicity in the relationships between cognition and the three risk scores using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Simple main effects and the interaction were considered. When examining the relationship between ethnicity, CAIDE, and cognition (Fig. 2), there was a main effect of CAIDE on cognition (F1,442 = 3.57, p = 0.008, partial η2 = 0.78) as well as a significant interaction (F1,442 = 2.03, p = 0.014, partial η2 = 0.06), but no significant main effect of ethnicity after accounting for CAIDE and the interaction term (F1,442 = 1.97, p = 0.17, partial η2 = 0.05). When not accounting for APOE risk in its calculation, there was still a significant main effect of CAIDE without APOE (F1,444 = 3.98, p = 0.006, partial η2 = 0.81), a main effect of ethnicity (F1,444 = 5.55, p = 0.024, partial η2 = 0.13), and their interaction was significant (F1,444 = 1.87, p = 0.032, partial η2 = 0.05). For FRS (Fig. 3), there was a significant main effect of FRS (F1,240 = 3.33, p = 0.003, partial η2 = 0.76) and ethnicity (F1,240 = 21.29, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.31), but the FRS × ethnicity interaction was not significant (F1,240 = 0.95, p = 0.52, partial η2 = 0.06). Lastly, for WHICAP (Fig. 4), there was a significant main effect of ethnicity (F1,368 = 1.75, p = 0.19, partial η2 = 0.03) and WHICAP (F1,368 = 6.00, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.91), but the WHICAP × ethnicity interaction was not significant (F1,368 = 0.81, p = 0.73, partial η2 = 0.05). Of note, unlike CAIDE and FRS, the WHICAP score already accounts for ethnicity in its calculation; thus, we examined WHICAP further by re-calculating WHICAP without race/ethnicity. Results revealed a significant main effect for WHICAP without race/ethnicity (F1,369 = 3.34, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.80), but the main effects for ethnicity (F1,369 = 1.71, p = 0.20, partial η2 = 0.03) and the WHICAP × ethnicity interaction (F1,369 = 1.41, p = 0.09, partial η2 = 0.09) were not significant.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between CAIDE and cognition by ethnicity.

Fig. 3.

Relationship between FRS and cognition by ethnicity.

Fig. 4.

Relationship between WHICAP and cognition by ethnicity.

For our third aim, we examined if the relationship between risk scores and cognition was being driven by a specific sub-domain or sub-domains that comprised the cognitive composite. Results of the regression analyses indicated that all three scores and the adjusted risk scores (i.e., CAIDE without APOE, WHICAP without race/ethnicity) significantly predicted performance across the five cognitive sub-domains (all ps < 0.001), but the strength of these relationships differed. As shown in Table 5, the largest effects for all three scores were observed in measures of attention and executive functioning abilities. The WHICAP score additionally demonstrated a large effect size in the relationship between the risk score and performances on measures of language abilities.

Table 5.

Parameter estimates and effect sizes for cognitive domains by risk score

| CAIDE | CAIDE without APOE | FRS | WHICAP | WHICAP without Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | R2 | p | β | R2 | p | β | R2 | p | β | R2 | p | β | R2 | p | |

| Executive | 0.40 | 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.42 | 0.18 | <0.001 | 0.32 | 0.1 | <0.001 | 0.57 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 0.29 | <0.001 |

| Language | −0.30 | 0.09 | <0.001 | −0.33 | 0.11 | <0.001 | −0.22 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.5 | 0.25 | <0.001 | −0.47 | 0.22 | <0.001 |

| Memory | −0.25 | 0.06 | <0.001 | −0.24 | 0.06 | <0.001 | −0.23 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.32 | 0.1 | <0.001 | −0.33 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Visuospatial | −0.27 | 0.07 | <0.001 | −0.29 | 0.08 | <0.001 | −0.28 | 0.08 | <0.001 | −0.4 | 0.16 | <0.001 | −0.38 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Attention | −0.46 | 0.22 | <0.001 | −0.48 | 0.23 | <0.001 | −0.33 | 0.11 | <0.001 | −0.58 | 0.34 | <0.001 | −0.55 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

Note: Higher executive functioning scores indicate worse performance.

Notably, the number of participants with sufficient data for the FRS risk index was much lower than the other two risk indices. Additional group comparisons of the subsamples with and without FRS data demonstrated some key differences. Those without FRS scores were more educated (11.40 versus 10.39 years of educations; p = 0.01) and had lower cognitive composite scores (−0.15 versus 0.27; p < 0.001). No significant differences were noted in terms of socioeconomic status or age. Gender proportions also differed between groups; the group without FRS had fewer men (175 female: 45 male) than the group with FRS (172 female: 111 male; p < 0.001). In response to these observed group differences, we ran a case-matched analysis that included only those individuals with all three scores (CAIDE, FRS, and WHICAP). This sub-sample consisted of only 213 individuals. While the effects were attenuated to some degree, the results of these analyses similarly demonstrated a pattern of different relationships across the three risk scores in the full sample: CAIDE [R2 = 0.18, F(1,212) = 46.00, p < 0.001], FRS [R2 = 0.13, F(1,212) = 32.00, p < 0.001], and WHICAP [R2 = 0.31, F(1,212) = 93.67, p < 0.001]. These results suggest the findings reported in the original full sample are not driven mainly by the demographic differences between those with and without an FRS.

DISCUSSION

Both modifiable (e.g., education) and unmodifiable (e.g., ethnic background) factors have been considered as potential risks for the onset of cognitive decline and AD. Risk scores have been developed as a way to predict one’s likelihood of cardiovascular events, dementia, and other health conditions. Many of the factors included in the calculation of risk scores are modifiable, thus they hold potential to be used in the context of prevention and targeting those modifiable risk factors. In the present study, we sought to examine the relationship between three risk scores—CAIDE, FRS, and WHICAP—and cognition in a diverse sample. The aims of the study were centered around two main objectives: to examine the strengths of the relationship between each RS and cognition and to examine how these relationships differ between ethnic groups (i.e., H/Ls and non-H/Ls). Our results suggest that all three risk scores are associated with cognition, but the strength of these relationships differed across the scores. Nevertheless, higher risk scores were associated with worse cognitive performance. This was despite the fact that not all three scores were developed to predict dementia risk; FRS is a score that attempts to predict risk for a cardiovascular incident (e.g., stroke, cardiovascular disease), though it should be noted that all three scores did assess vascular risk profiles. A substantial amount of literature suggests that cardiovascular risk factors are linked with an increased risk of cognitive decline and AD, which our results support. We believe that the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms associated with cardiovascular risk factors are significantly related to brain health and, therefore, cognitive abilities, which may put one at a higher risk of developing AD [40–43].

The WHICAP score was most strongly predictive of cognition, followed by the CAIDE, and FRS scores. Notably, though, the WHICAP score also had the greatest number of variables (11 variables) accounted for in the equation compared to CAIDE (8 variables) and FRS (7 variables; see Table 3). Initially, we believed the strength of the relationship between the WHICAP score and cognition could possibly be attributed, in part, to the inclusion of ethnicity as a risk factor when calculating the score, which was not considered in the calculation of FRS and CAIDE. Post-hoc analyses using WHICAP without race/ethnicity demonstrated that the model’s parameter estimates remained largely unchanged. These findings could be due to the context in which the WHICAP score was developed. As mentioned previously, WHICAP was developed using a large multiethnic urban sample, while both the CAIDE and FRS risk scores were created in highly homogeneous samples, thus, making WHICAP more generalizable and appropriate to use in diverse samples. These findings nonetheless support the importance of considering ethnic background in research and its associated increased risk for AD [44–46]. Indeed, subgroup analyses by ethnic background showed that the relationship between RSs and cognitive composite score was weaker in H/Ls than non-H/Ls across all three scores.

There is a lack of research in predicting risk for cognitive decline using RSs in H/L populations, although there are efforts towards developing risk indices for older H/L groups, such as the Mexican American Dementia Nomogram (MADeN), which is reportedly able to predict dementia with moderate accuracy [47]. Notably, our data did not include all the variables necessary to calculate the MADeN score, which includes such factors as walking ability and pain in addition to several of the variables that comprise the CAIDE, FRS, and WHICAP; therefore, we are unable to compare the MADeN to the three scores included here. The FRONTIER data included representation of both H/L and non-H/L individuals, allowing for comparisons between ethnic groups. Our findings provide support for the utility of RSs in H/L groups and help identify which of the risk scores may be more appropriate to use in this population.

This study has important limitations that warrant further discussion. First, one limitation is the use of a cross-sectional design that examined data from only one time point. Although this design provides valuable insight on how risk scores relate to current cognitive functioning, it would be beneficial to analyze the trends or changes in relationships longitudinally between RSs and cognition that may result as a change of lifestyle factors. Another factor that could contribute to slight discrepancies in the scoring was the modification done to the WHICAP score; BMI was substituted as a risk factor in place of waist-to-hip ratio. This modification can be justified by the fact that BMI and WHR are strongly correlated with each other; using the original variable would most likely only strengthen the observed relationships. In addition, research has shown that both BMI and waist-to-hip ratio have a combined effect on cognitive impairment [48], further justifying this modification. An additional factor that may have contributed to the difference in the strength of FRSs’ relationship with cognition is that the subsample of individuals that had a score available were different to those that did not in terms of gender, education, and current cognitive functioning. These are worth noting given that women are at a disproportionately higher risk of developing AD and related dementias and higher educational attainment is a notable protective factor against cognitive decline. However, when analyzing data from only individuals with all three risk scores, the same proportional differences remained between the risk scores. These findings suggest that differences between those with and without FRS data do not fully explain the findings in the full sample. Additionally, it should be noted that the H/L participants in Project FRONTIER were of lower SES and predominantly of Mexican descent (94% of those who identified as H/L). This is of importance given that previous research has found that prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors varies by H/L background and other demographic factors (e.g., U.S.-born) [49]. In the future, it would be beneficial to determine the predictive quality of RSs in terms of cognitive decline as it can reveal if these RSs can be reliably used as a predictor of AD in H/Ls, in addition to their utility in diverse H/L groups (e.g., Puerto Ricans versus Mexicans). As mentioned previously, the development of risk index scores specific to H/Ls is in its infancy and combined efforts to examine risk factors that are unique to H/Ls are needed in order to develop a tool that can predict risk of developing dementia in late adulthood.

Overall, the findings from this study suggest that all three risk scores (CAIDE, FRS, and WHICAP) can predict current cognitive ability, albeit at varying strengths. This is important to consider given that not all three risk scores were developed to predict dementia, as cardiovascular health plays a significant role in AD risk in ethno-racially diverse populations. This information will be useful as early preventative measures can be taken to avoid deterioration of brain health and possible progression to AD when an individual is at a high risk for cognitive decline.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG054073 and by a Summer Undergraduate Psychology Research Experience Grant (G0502934) from the American Psychological Association. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the American Psychological Association.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/19-1284r2).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-191284.

REFERENCES

- [1].Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, Holt JB, Croft JB, Mack D, McGuire LC (2019) Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015-2060) in adults aged>/=65 years. Alzheimers Dement 15, 17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jack CR Jr., Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, Liu E, Molinuevo JL, Montine T, Phelps C, Rankin KP, Rowe CC, Scheltens P, Siemers E, Snyder HM, Sperling R, Contributors (2018) NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 14, 535–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schoenberg MR, Duff K (2011) Dementias and mild cognitive impairment in adults. In The Little Black Book of Neuropsychology: A Syndrome-Based Approach, Schoenberg MR, Scott JG, eds. Springer, New York, pp. 357–404. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Garrett M (2018) A critique of the 2018 National Institute on Aging’s Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Neurobiol 9, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Whalley LJ, Dick FD, McNeill G (2006) A life-course approach to the aetiology of late-onset dementias. Lancet Neurol 5, 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cacace R, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C (2016) Molecular genetics of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease revisited. Alzheimers Dement 12, 733–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kuźma E, Lourida I, Moore SF, Levine DA, Ukoumunne OC, Llewellyn DJ (2018) Stroke and dementia risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement 14, 1416–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Xu W, Tan L, Wang HF, Jiang T, Tan MS, Tan L, Zhao QF, Li JQ, Wang J, Yu JT (2015) Meta-analysis of modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 86, 1299–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Arce Rentería M, Vonk JMJ, Felix G, Avila JF, Zahodne LB, Dalchand E, Frazer KM, Martinez MN, Shouel HL, Manly JJ (2019) Illiteracy, dementia risk, and cognitive trajectories among older adults with low education. Neurology 93, e2247–e2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Reitz C, Tang M-X, Schupf N, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA (2010) A summary risk score for the predicttion of Alzheimer disease in elderly persons. JAMA Neurol 67, 835–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, Myers RH, Pericak-Vance MA, Risch N, van Duijn CM (1997) Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between Apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis. JAMA 278, 1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Blue EE, Horimoto ARVR, Mukherjee S, Wijsman EM, Thornton TA (2019) Local ancestry at APOE modifies Alzheimer’s disease risk in Caribbean Hispanics. Alzheimers Dement 15, 1524–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Vega IE, Cabrera LY, Wygant CM, Velez-Ortiz D, Counts SE (2017) Alzheimer’s disease in the Latino community: Intersection of genetics and social determinants of health. J Alzheimers Dis 58, 979–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mayeda ER, Karter AJ, Huang ES, Moffet HH, Haan MN, Whitmer RA (2014) Racial/ethnic differences in dementia risk among older type 2 diabetic patients: The diabetes and aging study. Diabetes Care 37, 1009–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stickel A, McKinnon A, Ruiz J, Grilli MD, Ryan L, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2019) The impact of cardiovascular risk factors on cognition in Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. Learn Mem 26, 235–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dilworth-Anderson P, Hendrie HC, Manly JJ, Khachaturian AS, Fazio S (2008) Diagnosis and assessment of Alzheimer’s disease in diverse populations. Alzheimers Dement 4, 305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hall LML, Jung RT, Leese GP (2003) Controlled trial of effect of documented cardiovascular risk scores on prescribing. BMJ 326, 251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sacco RL, Khatri M, Rundek T, Xu Q, Gardener H, Boden-Albala B, Di Tullio MR, Homma S, Elkind MS, Paik MC (2009) Improving global vascular risk prediction with behavioral and anthropometric factors. The multiethnic NOMAS (Northern Manhattan Cohort Study). J Am Coll Cardiol 54, 2303–2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Laatikainen T, Winblad B, Soininen H, Tuomilehto J (2006) Risk score for the prediction of dementia risk in 20 years among middle aged people: A longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Neurol 5, 735–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tsao CW, Vasan RS (2015) Cohort Profile: The Framingham Heart Study (FHS): Overview of milestones in cardiovascular epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 44, 1800–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].D’Agostino RB Sr., Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB (2008) General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 117, 743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Filshtein TJ, Dugger BN, Jin LW, Olichney JM, Farias ST, Carvajal-Carmona L, Lott P, Mungas D, Reed B, Beckett LA, DeCarli C (2019) Neuropathological diagnoses of demented Hispanic, Black, and Non-Hispanic White decedents seen at an Alzheimer’s disease center. J Alzheimers Dis 68, 145–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Anstey KJ, Cherbuin N, Herath PM (2013) Development of a new method for assessing global risk of Alzheimer’s disease for use in population health approaches to prevention. Prev Sci 14,411–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kaffashian S, Dugravot A, Elbaz A, Shipley MJ, Sabia S, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A (2013) Predicting cognitive decline: A dementia risk score vs. the Framingham vascular risk scores. Neurology 80, 1300–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ecay-Torres M, Estanga A, Tainta M, Izagirre A, Garcia-Sebastian M, Villanua J, Clerigue M, Iriondo A, Urreta I, Arrospide A, Diaz-Mardomingo C, Kivipelto M, Martinez-Lage P (2018) Increased CAIDE dementia risk, cognition, CSF biomarkers, and vascular burden in healthy adults. Neurology 91, e217–e226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kivimäki M, Shipley MJ, Allan CL, Sexton CE, Jokela M, Virtanen M, Tiemeier H, Ebmeier KP, Singh-Manoux A (2012) Vascular risk status as a predictor of later-life depressive symptoms: A cohort study. Biol Psychiatry 72, 324–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tosto G, Bird TD, Bennett DA, Boeve BF, Brickman AM, Cruchaga C, Faber K, Foroud TM, Farlow M, Goate AM, Graff-Radford NR, Lantigua R, Manly J, Ottman R, Rosenberg R, Schaid DJ, Schupf N, Stern Y, Sweet RA, Mayeux R, National Institute on Aging Late-Onset Alzheimer Disease/National Cell Repository for Alzheimer Disease (NIA-LOAD/NCRAD) Family Study Group (2016) The role of cardiovascular risk factors and stroke in familial Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 73, 1231–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].O’Bryant SE, Edwards M, Menon CV, Gong G, Barber R (2011) Long-term low-level arsenic exposure is associated with poorer neuropsychological functioning: A Project FRONTIER study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8, 861–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Morris JC (1993) The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43, 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Royall DR, Cordes JA, Polk M (1998) CLOX: An executive clock drawing task. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 64, 588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Royall DR, Mahurin RK, Gray KF (1992) Bedside assessment of executive cognitive impairment: The executive interview. J Am Geriatr Soc 40, 1221–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tombaugh TN, Kozak J, Rees L (1999) Normative data stratified by age and education for two measures of verbal fluency: FAS and animal naming. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 14, 167–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Army Individual Test Battery (1944) Manual of directions and scoring. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN (1998) The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): Preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 20, 310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hooshmand B, Polvikoski T, Kivipelto M, Tanskanen M, Myllykangas L, Makela M, Oinas M, Paetau A, Solomon A (2018) CAIDE Dementia Risk Score, Alzheimer and cerebrovascular pathology: A population-based autopsy study. J Intern Med 283, 597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lloyd-Jones DM, Wilson PW, Larson MG, Beiser A, Leip EP, D’Agostino RB, Levy D (2004) Framingham risk score and prediction of lifetime risk for coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 94, 20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB (1998) Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 97, 1837–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Jahangiry L, Farhangi MA, Rezaei F (2017) Framingham risk score for estimation of 10-years of cardiovascular diseases risk in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Health Popul Nutr 36, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].IBM Corp. (2017) IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh. Armonk, NY. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Leritz EC, McGlinchey RE, Kellison I, Rudolph JL, Milberg WP (2011) Cardiovascular disease risk factors and cognition in the elderly. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 5, 407–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kumral D, Schaare HL, Beyer F, Reinelt J, Uhlig M, Liem F, Lampe L, Babayan A, Reiter A, Erbey M, Roebbig J, Loeffler M, Schroeter ML, Husser D, Witte AV, Villringer A, Gaebler M (2019) The age-dependent relationship between resting heart rate variability and functional brain connectivity. Neuroimage 185, 521–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Stampfer MJ (2006) Cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease: Common links. J Intern Med 260, 211–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Silvestrini M, Gobbi B, Pasqualetti P, Bartolini M, Baruffaldi R, Lanciotti C, Cerqua R, Altamura C, Provinciali L, Vernieri F (2009) Carotid atherosclerosis and cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 30, 1177–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Maestre G, Ottman R, Stern Y, Gurland B, Chun M, Tang M-X, Shelanski M, Tycko B, Mayeux R (1995) Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer’s disease: Ethnic variation in genotypic risks. Ann Neurol 37, 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rajan KB, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Weuve J, McAninch EA, Evans DA (2019) Apolipoprotein E genotypes, age, race, and cognitive decline in a population sample. J Am Geriatr Soc 67, 734–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Morris JC, Schindler SE, McCue LM, Moulder KL, Benzinger TLS, Cruchaga C, Fagan AM, Grant E, Gordon BA, Holtzman DM, Xiong C (2019) Assessment of racial disparities in biomarkers for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 76, 264–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Downer B, Kumar A, Veeranki SP, Mehta HB, Raji M, Markides KS (2016) Mexican-American dementia nomogram: Development of a dementia risk index for Mexican-American older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 64, e265–e269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Liu Z, Yang H, Chen S, Cai J, Huang Z (2018) The association between body mass index, waist circumference, waist—hip ratio and cognitive disorder in older adults. J Public Health 41, 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Aviles-Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, Gellman M, Giachello AL, Gouskova N, Kaplan RC, LaVange L, Penedo F, Perreira K, Pirzada A, Schneiderman N, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Sorlie PD, Stamler J (2012) Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA 308, 1775–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.