Abstract

The water and glycerol channel, aquaporin-3 (AQP3), plays an important role in the skin epidermis, with effects on hydration, permeability barrier repair and wound healing; therefore, information about the mechanisms regulating its expression is important for a complete understanding of skin function physiologically and in disease conditions. We previously demonstrated that histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) induce the mRNA and protein expression of AQP3, in part through the p53 family, transcription factors for which acetylation is known to affect their regulatory activity. Another set of transcription factors previously shown to induce AQP3 expression and/or regulate skin function are the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). Since there are reports that PPARs are also acetylated, we examined the involvement of these nuclear hormone receptors in HDACi-induced AQP3 expression. We first verified that a PPARγ agonist upregulated AQP3 mRNA and protein levels and that this increase was blocked by a PPARγ antagonist. We then showed that the PPARγ antagonist also inhibited AQP3 expression induced both by a broad spectrum HDACi and an HDAC3-selective inhibitor. Interestingly, a PPARα antagonist also inhibited HDACi-induced AQP3 expression. These antagonist effects were observed in both primary mouse and normal human keratinocytes. Furthermore, PPARγ overexpression enhanced HDACi-stimulated AQP3 mRNA levels. Thus, our results suggest that PPARγ and/or PPARα may play a role in regulating AQP3 levels in the skin; based on the ability of PPAR agonists to promote epidermal differentiation and/or inhibit proliferation, topical PPAR agonists might be considered as a therapy for hyperproliferative skin disorders, such as psoriasis.

Keywords: acetylation, aquaporin-3 (AQP3), epidermis, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), skin

Introduction

The aquaglyceroporin aquaporin-3 (AQP3) is the predominant member of the aquaporin family expressed in the epidermis of the skin (reviewed in [1]). Capable of transporting water and other small molecules, such as glycerol and hydrogen peroxide [2–4], this channel is thought to play an important role in multiple epidermal functions, including hydration, barrier function/repair and wound healing (reviewed in [1, 5]). Thus, AQP3 knockout mice exhibit an epidermal phenotype with decreased capacitance, reduced skin elasticity, impaired barrier repair after disruption and delayed wound healing [2, 6]. These abnormalities are related to the ability of AQP3 to transport glycerol as these mice display reduced epidermal glycerol content [6], and the epidermal phenotype can be rescued by oral, topical or intraperitoneal administration of pharmacological amounts of glycerol [7]. Fluhr et al. [8] also described a key role for glycerol in regulating epidermal keratinocyte proliferation: in an asebia mouse model that fails to produce sebum, epidermal glycerol content is reduced and the epidermis is hyperplastic. This phenotype can be rescued by topical application of glycerol but not another humectant (urea), again supporting an important role for AQP3-transported glycerol in skin function [8]. Additional studies in humans also are consistent with the importance of glycerol in healthy and diseased skin [9–13].

Given the critical role of AQP3 in skin, it is important to identify the factors regulating AQP3 expression as well as the mechanisms underlying its effects in the epidermis. The role of epigenetics in regulating AQP3 remains largely unexplored. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, a relatively new group of epigenetic agents, are being investigated as possible therapies to treat a variety of human diseases, because of their powerful anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, pro-differentiative and pro-apoptotic effects (reviewed in [14–16]). HDACs remove acetyl groups from histones and other proteins, including transcription factors, thereby modulating gene expression (discussed in [17]). HDACs are known to be very important in the epidermis as, for example, keratinocyte-specific ablation of HDAC1 and 2 results in abnormal epidermal proliferation and stratification [18]. Our laboratory recently found that a broad-spectrum HDAC inhibitor, suberolyanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), as well as an HDAC3-selective inhibitor (RGFP966), increases AQP3 expression in keratinocytes [17]. Furthermore, overexpression of HDAC3 reduces, and knockdown of HDAC3 increases, AQP3 mRNA and protein levels [17]. These results indicate an important role of this HDAC in regulating AQP3 expression in skin.

Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) activators are also known to regulate AQP3 expression, increasing APQ3 mRNA and protein levels and epidermal lipid production [19]. PPAR transcriptional activity has been found to be regulated by various post-translational modifications including acetylation (reviewed in [20]). In a 2014 study in adipocytes, Jiang et al. [21] reported that PPARγ acetylation induced by an HDAC3 inhibitor promoted PPARγ acetylation and adipocyte function. Indeed, HDAC3 and pRb protein have been shown to form a repressor complex to inhibit PPARγ activity and adipogenesis (reviewed in [22]). However, it is unknown whether the effects of HDAC inhibitors on AQP3 expression are related to PPARγ action in epidermal keratinocytes. Here, we demonstrate an involvement of PPARs in the AQP3 expression induced by HDAC inhibition.

Methods

Keratinocyte Isolation and Culture

Keratinocytes were isolated and cultured as previously described [23]. Briefly, after sacrifice, skins were harvested from 1- to 3-day-old neonatal mice according to protocols approved by Augusta University and the Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. After flotation of the skins at 4°C in a trypsin solution overnight, the epidermis was separated from the dermis and gently scraped to release keratinocytes. Keratinocytes were collected by centrifugation, counted and plated in tissue culture plates in plating medium overnight as described in [24]. The medium was then replaced with a keratinocyte serum-free medium (K-SFM; Lonza, Inc., Walkersville, MD) and the cells cultured with replacement of medium every 2 days until experimentation. Normal human keratinocytes were purchased from Lonza and were cultured according to the supplier’s instructions.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

After treatment of the cells with the indicated agents for 18 hours, total RNA was isolated and quantified by quantitative RT-PCR using Taqman primer-probe sets from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA), as described previously [17].

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously [17]. Briefly, treated cells were lysed with an SDS-containing lysis buffer. Proteins (in equal volumes of lysate) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to Immobilon P (Millipore). After blocking, blots were incubated with primary antibodies followed by appropriate IRDye-coupled secondary antibodies, and immunoreactive bands were visualized and quantified using a Licor Odyssey instrument according to the manufacturer’s directions.

Adenovirus-Mediated PPAR Overexpression

Adenoviruses expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP), PPARα or PPARγ (obtained from Vector Biolabs, Malvern, PA) were propagated and isolated as described previously [23]. Keratinocytes were infected with these adenoviruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20 in K-SFM for 24 hours. The adenovirus-containing medium was aspirated and replaced with adenovirus-free medium, and the cells incubated with and without 2.5μM SAHA for an additional 18 hours. The cells were harvested and mRNA and protein levels determined by qRT-PCR and Western analysis, respectively, as described above.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the means ± SEM of at least three separate experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls post-hoc comparison as performed by GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA).

Results

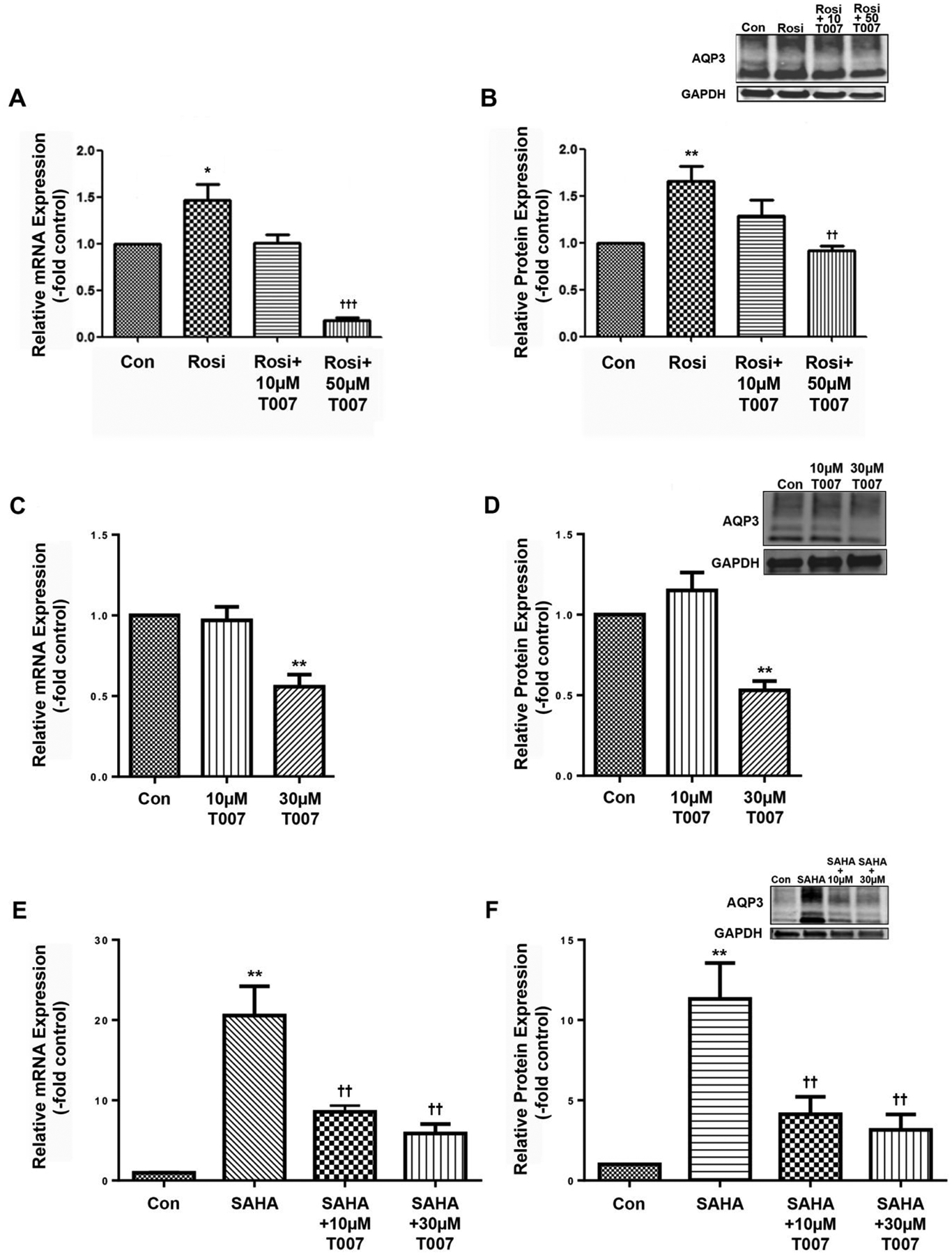

Based on data in adipocytes suggesting an interaction between HDAC3 and PPARγ [21] and our own recent results demonstrating a role for HDAC3 in regulating AQP3 expression [17], we investigated the involvement of PPARs in modulating HDAC inhibitor-induced AQP3 mRNA and protein levels in epidermal keratinocytes. To do so, we first determined the ability of a PPARγ antagonist to inhibit the increased AQP3 expression in response to a PPARγ agonist, Rosiglitazone (Rosi), to verify the efficacy of the antagonist in this system. As shown previously in normal human keratinocytes [19], treatment of primary cultures of mouse epidermal keratinocytes with Rosiglitazone (10 μM) elevated AQP3 mRNA (Figure 1A) and protein levels (Figure 1B). The PPARγ antagonist, T0070907 (T007) inhibited these Rosi-induced increases in AQP3 expression, with the 10 μM concentration returning levels to values not significantly different from the control and the 50 μM dose reducing levels below control (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1. T007 inhibited AQP3 expression induced by the PPARγ agonist Rosiglitazone or the pan-HDAC inhibitor SAHA in primary mouse keratinocytes.

Cells were treated with or without 10μM Rosiglitazone (Rosi) in the presence and absence of the PPARγ antagonist T0070907 (T007) at a concentration of 10 or 50μM. (A) qRT-PCR showing AQP3 expression and (B) a representative Western blot and quantitation of multiple experiments are shown; *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus control; ††p<0.01, †††p<0.001 versus Rosi alone (n=3). (C-F) Cells were treated with or without 2.5μM SAHA in the presence and absence of 10 or 30μM T007. (C) qRT-PCR of AQP3 expression and (D) a representative Western blot and band quantitation are shown in the absence of SAHA; **p<0.01 versus control. (E) qRT-PCR of AQP3 expression and (F) a representative Western blot and band quantitation are shown in the presence of SAHA; **p<0.01 versus control; ††p<0.01 versus SAHA alone.

We were concerned that the 50 μM dose might be excessive, so we determined the effect of PPARγ inhibition on basal AQP3 expression by treating keratinocytes with 10 and 30 μM concentrations and examining AQP3 expression. As shown in Figure 1C and D, T007 at 30 but not 10 μM inhibited basal AQP3 mRNA and protein levels. We then examined the effect of this antagonist on the increase in AQP3 expression elicited by the pan-HDAC inhibitor, SAHA. As shown in Figure 1E and F, SAHA induced a large elevation in APQ3 mRNA and protein levels, as we have previously observed [17]; importantly, T007 significantly inhibited this increase at both the low (10 μM) and the high (30 μM) dose.

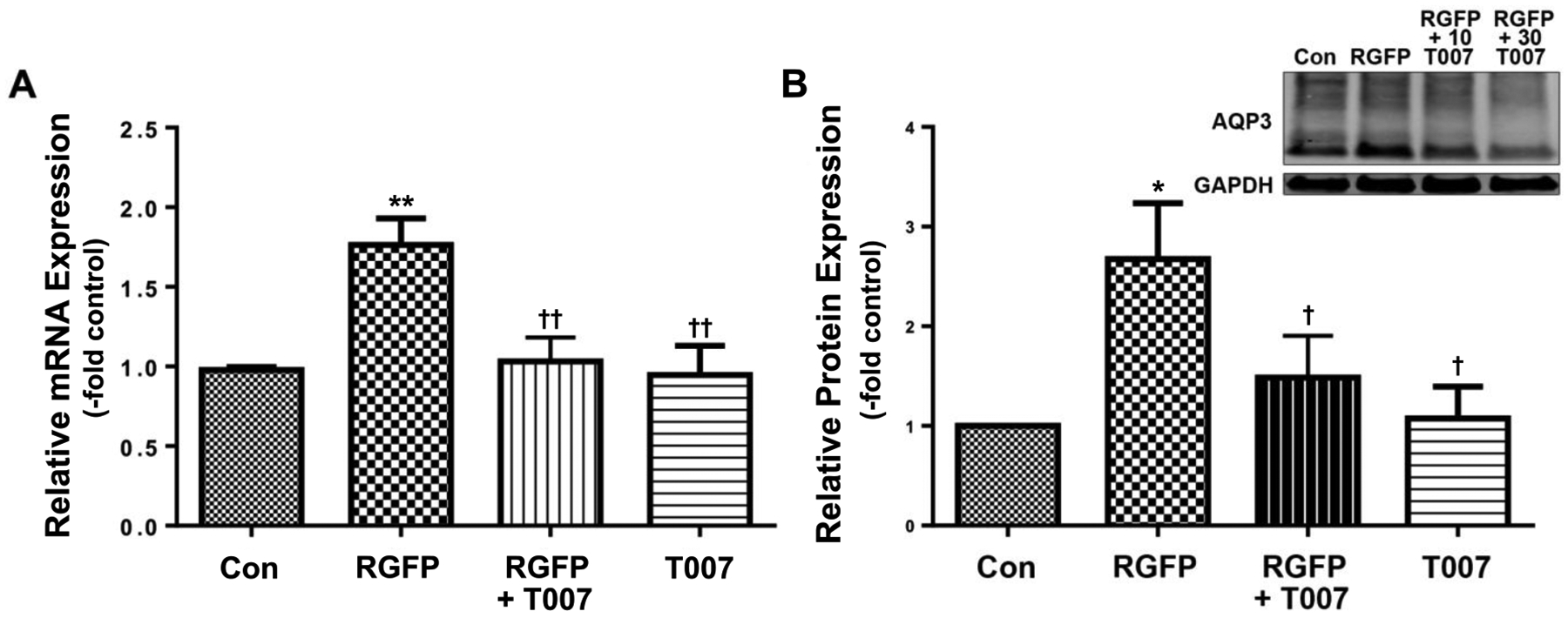

We also examined the ability of this antagonist to inhibit the induction of AQP3 expression in response to the HDAC3-selective inhibitor RGFP966 (RGFP). Again as previously described [17], RGFP enhanced AQP3 mRNA and protein levels (Figure 2A and B), and T007 reduced this effect. These results suggest the possible involvement of PPARγ in the regulation of AQP3 expression as well as its interaction with HDACs, and in particular HDAC3. We also examined the effect of HDAC inhibition on the expression of some known PPAR target genes, including Scd1, perilipin 1, Klf15 and HmgcsS2. The mRNA levels of most of these genes were undetectable (perilipin 1) or at such low abundance the accuracy of the results was called into question (data not shown). Likewise, the expression of PPARγ in keratinocytes was so low as to be only occasionally detectable (data not shown). Only PPARα and Hmgcs2, a gene involved in ketogenesis, were regulated by HDAC inhibition, exhibiting a significant approximately 3-fold and 6–fold increase, respectively, in response to SAHA (Supplemental Figure 1A and B). RGFP966 showed a similar trend to upregulate these two genes but the values did not attain statistical significance (Supplemental Figure 1C and D).

Figure 2. The PPARγ antagonist T007 reduced AQP3 expression induced by RGFP966.

Cells were treated with or without 15μM RGFP (RGFP) in the presence and absence of 10μM T0070907 (T007). (A) qRT-PCR showing AQP3 expression and (B) a representative Western blot and quantitation of multiple experiments are shown; *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus control; †p<0.05, ††p<0.01 versus RGFP966 alone (n=3).

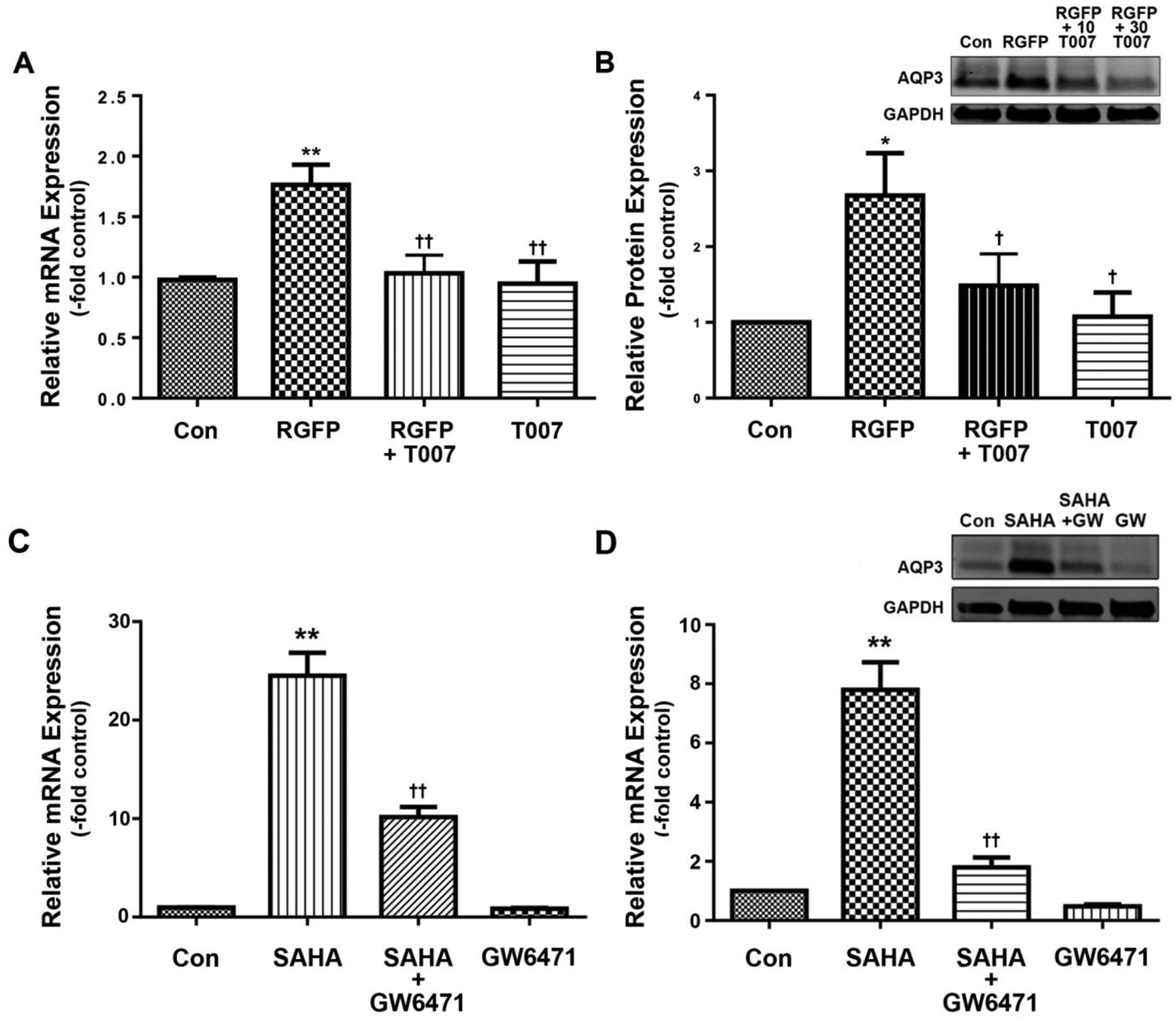

On the other hand, PPARγ is only one member of the PPAR family of nuclear hormone receptors. Indeed, our data suggested a greater expression of PPARα than PPARγ in keratinocytes as well as an upregulation of PPARα expression by HDAC inhibition. Furthermore, PPARα agonists have also been reported to regulate keratinocytes biology and skin function [25–28], and mice lacking PPARα exhibit a skin developmental phenotype [29]. We therefore investigated the role of PPARα in HDAC inhibitor-induced AQP3 expression in mouse keratinocytes. First, we demonstrated that the PPARα agonist CP775146 (CP755) increased AQP3 expression and that this induction was inhibited by the PPARα antagonist GW6471 at a concentration of 10 μM (Figure 3A). We then treated keratinocytes with and without SAHA in the presence and absence of the PPARα antagonist, GW6471. We found that GW6471 inhibited the SAHA-elicited increase in AQP3 mRNA and protein levels without affecting these parameters basally (Figure 3B and C). GW6471 also inhibited the induction of AQP3 expression by RGFP (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. The PPARα antagonist GW6471 reduced AQP3 expression induced by SAHA or RGFP966 in primary mouse keratinocytes.

Cells were treated with or without (A) the PPARα agonist CP755146 (CP755, 10 μM), (B and C) 2.5 μM SAHA or (D) 15μM RGFP (RGFP) in the presence and absence of 10μM GW6471. (A, B and D) qRT-PCR of AQP3 expression and (C) a representative Western blot and band quantitation are shown; *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus control; †p<0.05, ††p<0.01 versus CP755146, RGFP or SAHA alone.

Based on the low expression levels of PPARγ and the possible lack of specificity of PPAR agonists and antagonists, we investigated the ability of the PPARα antagonist GW6471 to inhibit Rosi-induced AQP3 expression as well as the effect of the PPARγ inhibitor T007 on the induction of AQP3 expression by a PPARα agonist, CP775. As shown in Supplemental Figure 2A, GW6471 inhibited AQP3 mRNA levels in the presence and absence of Rosi. Likewise, T007 reduced AQP3 mRNA levels in the presence and absence of CP775 (Supplemental Figure 2B). This result suggests that either the PPAR antagonists or the PPAR agonists, or both, are not entirely selective for their reported targets. Nevertheless, the combination of T007 and GW6471 completely blocked SAHA-induced AQP3 expression (Supplemental Figure 3).

The above results suggested a lack of specificity of either the PPAR agonists and/or the PPAR antagonists. Therefore, we determined the effect of overexpressing PPARα and PPARγ on AQP3 mRNA levels alone and upon stimulation with SAHA. We found that overexpression of either PPARα or PPARγ alone up-regulated AQP3 mRNA and protein expression (for mRNA levels, approximately 2- and 13-fold, respectively), although these increases did not achieve statistical significance (Figure 4). SAHA seemed to have no additional effect on AQP3 mRNA levels in PPARα-overexpressing cells but significantly and markedly enhanced AQP3 expression in PPARγ-overexpressing mouse keratinocytes (Figure 4), suggesting that PPARγ is the receptor primarily affected by HDAC inhibition.

Figure 4. Overexpression of PPARγ enhanced the ability of SAHA to induce AQP3 expression in primary mouse keratinocytes.

Cells were infected with adenoviruses expressing GFP (control), PPARα or PPARγ as indicated for 24 hours before treatment with or without 2.5 μM SAHA for 18 hours. Panel (A) shows a representative Western blot demonstrating PPARα overexpression and Panel (B) PPARγ overexpression. (C) Mean values ± SEM of AQP3 mRNA expression from 3 separate experiments are shown; †††p<0.001 versus all other values. Panel (D) shows a representative Western blot and panel (E) the mean values ± SEM of AQP3 protein levels from 3 separate experiments; **p<0.01 versus the GFP control, fp<0.05 as indicated.

Similarly to mouse keratinocytes, normal human keratinocytes (NHKs) also demonstrated increased AQP3 expression in response to SAHA treatment [17]. We determined whether in NHKs this induction of APQ3 by SAHA involved PPARs. We first confirmed that T007 inhibited AQP3 expression induced by Rosi (data not shown). We then examined the effect of this inhibitor, as well as that of the PPARα inhibitor GW6471, on AQP3 expression and determined that T007 (Supplemental Figure 4A and B) and GW6471 (Supplemental Figure 4C) each inhibited SAHA-elicited AQP3 expression in NHKs, without significantly altering basal levels.

Discussion

Our results suggest that inhibition of HDACs, and in particular HDAC3, promotes AQP3 expression at least in part through activating PPAR-mediated transcription. Thus, both PPARγ and PPARα antagonists were able to reduce the AQP3 expression induced by HDAC inhibition. These effects were observed in mouse and human keratinocytes, suggesting some species conservation of this mechanism. Interestingly, the involvement of the PPARs occurred in the absence of added PPAR agonists. This result suggests that endogenous PPAR agonists are basally produced to a certain extent or that in keratinocytes the PPARs exhibit ligand-independent activation. The latter idea is supported by data demonstrating an ability of PPARγ to repress gene transcription in a ligand-independent manner (reviewed in [21]). In addition, in adipocytes an increase in PPARγ acetylation induced by HDAC3 inhibition was found to result in a ligand-independent activation of PPARγ’s actions both in vitro and in vivo [21]. Indeed, in that study HDAC3 and PPAR formed a co-immunoprecipitable complex [21]. This result suggests that AQP3 induction by HDAC inhibition might be direct through effects on acetylation of transcription factors such as PPAR rather than through an indirect action to increase chromatin accessibility by the transcriptional machinery, although the possibility of this latter effect cannot be excluded.

Also of interest is the fact that antagonists reported to be selective for both PPARα and PPARγ were effective at inhibiting AQP3 expression induced by HDAC inhibition. It should be noted that an interaction between HDAC3 and PPARα was described for the FGF21 promoter in a hepatocyte cell line (HepG2) and liver [30], and, in fact, many of the mechanisms by which the PPARs regulate gene transcription are thought to be identical for PPARα and PPARγ (reviewed in [31]). However, we showed that GW6471, a reported PPARα antagonist, inhibited the ability of the supposed PPARγ agonist Rosi to induce AQP3 expression, and T007, a supposed PPARγ antagonist reduced AQP3 expression induced by a reported PPARα agonist, CP775, suggesting the likelihood that these reagents are not as selective as they are described to be. Based on the very low expression levels of PPARγ in keratinocytes (often undetectable) and the ability of HDAC inhibition to induce PPARα expression, we initially speculated that PPARα was the key receptor interacting with HDAC inhibition to upregulate AQP3 expression. However, our data showing that SAHA significantly enhanced AQP3 levels in cells with adenovirus-mediated overexpression of PPARγ, but not PPARα, suggest instead that PPARγ is the receptor interacting with HDAC inhibition to up-regulate AQP3 expression. Alternatively, it is possible that PPARα is already sufficiently abundant in keratinocytes such that additional (over)expression is not effective in increasing AQP3 levels with SAHA treatment.

Both PPARα and PPARγ have been reported to regulate skin function in a similar manner. Thus, PPARα and PPARγ agonists inhibit skin inflammation and epidermal proliferation and promote keratinocyte differentiation and epidermal permeability barrier function [27, 29, 32]. On the other hand, gene knock out of PPARγ through genetic manipulation has a minimal effect on skin inflammation, epidermal differentiation and skin ontogenesis while enhancing epidermal proliferation (reviewed in [33]); however, loss of PPARα results in increased skin inflammation, slightly reduced epidermal differentiation and impaired skin ontogenesis with no effect on proliferation [33]. Together, the fact that the results observed with PPAR agonists are not necessarily opposite to the effects of PPAR gene loss again supports the idea that the PPAR agonists are perhaps not as selective as reported. Nevertheless, although many of the processes regulated by these two nuclear hormone receptors are similar, PPARα and PPARγ clearly show differences in terms of their function in skin, and further genetic studies to determine their role in regulating AQP3 expression induced by HDAC inhibition, as well as the involvement of this AQP3 upregulation in the effects of PPARs, are obviously necessary.

An HDAC inhibitor is already in use to treat cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, a type of cancer in which malignant T lymphocytes are found in the skin. Although vorinostat (also known as SAHA) is an approved therapy for this disease, the exact mechanism of its anti-neoplastic action has not been fully characterized. The thiazolidinediones (TZDs), known agonists of the PPARs, have also been proposed as potential tools in the armamentarium of therapies for the treatment of hyperproliferative and other skin diseases, such as psoriasis and melanoma (reviewed in [34]). Our studies showing an anti-proliferative and pro-differentiative role for AQP3 in keratinocytes (reviewed in [1, 5]), together with ours and others’ results concerning the ability of PPARs to regulate AQP3 expression, support this idea. Skin has the advantage that drugs can be administered topically with excipients that can be designed to minimize systemic drug delivery. Thus, our results suggest that topical application of TZDs, with or without co-administration of HDAC inhibitors, may be a useful strategy to treat various skin disorders, particularly those characterized by abnormal AQP3 expression (reviewed in [5]).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We express our appreciation for the expert technical assistance of Ms. Purnima Merai. RY was supported by grant #06000031 from Jianghan University. This work was also supported in part by VA Merit #CX001357 to WBB. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Patel R, Kevin Heard L, Chen X, and Bollag WB, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 2017. 969: p. 173–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma T, Hara M, Sougrat R, Verbavatz JM, and Verkman AS, J. Biol. Chem 2002. 277: p. 17147–17153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller EW, Dickinson BC, and Chang CJ, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010. 107(36): p. 15681–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hara-Chikuma M, Satooka H, Watanabe S, Honda T, Miyachi Y, Watanabe T, and Verkman AS, Nat. Commun 2015. 6: p. 7454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin H, Zheng X, Zhong X, Shetty AK, Elias PM, and Bollag WB, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2011. 508: p. 138–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hara M, Ma T, and Verkman AS, J. Biol. Chem 2002. 277: p. 46616–46621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hara M and Verkman AS, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003. 100: p. 7360–7365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fluhr JW, Mao-Qiang M, Brown BE, Wertz PW, Crumrine D, Sundberg JP, Feingold KR, and Elias PM, J. Invest. Dermatol 2003. 120: p. 728–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fluhr JW, Gloor M, Lehmann L, Lazzerinin S, Distante F, and Berardesca E, Acta Derm. Venereol 1999. 79: p. 418–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fluhr JW, Darlenski R, and Surber C, Br. J. Dermatol 2008. 159: p. 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi EH, Man M-Q, Wang F, Zhang X, Brown BE, Feingold KE, and Elias PM, J. Invest. Dermatol 2005. 125: p. 288–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korponyai C, Szel E, Behany Z, Varga E, Mohos G, Dura A, Dikstein S, Kemeny L, and Eros G, Acta Derm. Venereol 2017. 97(2): p. 182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee Y, Je YJ, Lee SS, Li ZJ, Choi DK, Kwon YB, Sohn KC, Im M, Seo YJ, and Lee JH, Ann. Dermatol 2012. 24(2): p. 168–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dinarello CA, Cell 2010. 140(6): p. 935–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLaughlin F and La Thangue NB, Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy 2004. 3(2): p. 213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shuttleworth SJ, Bailey SG, and Townsend PA, Curr. Drug Targets 2010. 11(11): p. 1430–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choudhary V, Olala LO, Kagha K, Pan ZQ, Chen X, Yang R, Cline A, Helwa I, Marshall L, Kaddour-Djebbar I, McGee-Lawrence ME, and Bollag WB, J. Invest. Dermatol 2017. 137: p. 1935–1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeBoeuf M, Terrell A, Trivedi S, Sinha S, Epstein JA, Olson EN, Morrisey EE, and Millar SE, Dev. Cell 2010. 19(6): p. 807–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang YJ, Kim P, Lu YF, and Feingold KR, Exp. Dermatol 2011. 20: p. 595–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunmeir R and Xu F, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2018. 19(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang X, Ye X, Guo W, Lu H, and Gao Z, J. Mol. Endocrinol 2014. 53(2): p. 191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miard S and Fajas L, Int. J. Obes 2005. 29 Suppl 1: p. S10–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choudhary V, Olala LO, Qin H, Helwa I, Pan ZQ, Tsai YY, Frohman MA, Kaddour-Djebbar I, and Bollag WB, J. Invest. Dermatol 2015. 135: p. 499–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung EM, Betancourt-Calle S, Mann-Blakeney R, Griner RD, and Bollag WB, Carcinogenesis 1999. 20: p. 569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komuves LG, Hanley K, Lefebvre AM, Man MQ, Ng DC, Bikle DD, Williams ML, Elias PM, Auwerx J, and Feingold KR, J. Invest. Dermatol 2000. 115(3): p. 353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komuves LG, Hanley K, Man MQ, Elias PM, Williams ML, and Feingold KR, J. Invest. Dermatol 2000. 115(3): p. 361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanley K, Jiang Y, Crumrine D, Bass NM, Appel R, Elias PM, Williams ML, and Feingold KR, J. Clin. Invest 1997. 100(3): p. 705–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanley K, Jiang Y, He SS, Friedman M, Elias PM, Bikle DD, Williams ML, and Feingold KR, J. Invest. Dermatol 1998. 110(4): p. 368–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmuth M, Schoonjans K, Yu QC, Fluhr JW, Crumrine D, Hachem JP, Lau P, Auwerx J, Elias PM, and Feingold KR, J. Invest. Dermatol 2002. 119(6): p. 1298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Gao Z, Zhang J, Ye X, Xu A, Ye J, and Jia W, Diabetes 2012. 61(4): p. 797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kota BP, Huang TH, and Roufogalis BD, Pharmacol. Res 2005. 51(2): p. 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao-Qiang M, Fowler AJ, Schmuth M, Lau P, Chang S, Brown BE, Moser AH, Michalik L, Desvergne B, Wahli W, Li M, Metzger D, Chambon PH, Elias PM, and Feingold KR, J. Invest. Dermatol 2004. 123(2): p. 305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmuth M, Jiang YJ, Dubrac S, Elias PM, and Feingold KR, J. Lipid Res 2008. 49(3): p. 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta M, Mahajan VK, Mehta KS, Chauhan PS, and Rawat R, Arch. Dermatol. Res 2015. 307(9): p. 767–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.