Abstract

Background:

Protective ventilation may improve outcomes following major surgery. However, in the context of one lung ventilation the definition of such a strategy is incompletely defined. We hypothesized that a putative one lung protective ventilation regimen would be independently associated with decreased odds of pulmonary complications following thoracic surgery.

Methods:

We merged Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database and Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group intraoperative data for lung resection procedures using one lung ventilation across five institutions from 2012 to 2016. We defined one lung protective ventilation as the combination of both median tidal volume ≤5 ml/kg predicted body weight and positive end expiratory pressure ≥5 cm H2O. The primary outcome was a composite of 30-day major postoperative pulmonary complications.

Results:

3,232 cases were available for analysis. Tidal volumes decreased modestly during the study period (6.7 ml/kg to 6.0 ml/kg, p < 0.001) and positive end expiratory pressure increased from 4 to 5 cm H2O (p < 0.001). Despite increasing adoption of a “protective ventilation” strategy (5.7% in 2012 versus 17.9% in 2016), the prevalence of pulmonary complications did not change significantly (11.4% to 15.7%, p = 0.147). In a propensity score matched cohort (381 matched pairs), protective ventilation (mean tidal volume 6.4 vs 4.4 mL/kg) was not associated with a reduction in pulmonary complications (adjusted odds ratio 0.86, 95% confidence interval 0.56, 1.32). In an unmatched cohort, we were unable to define a specific alternative combination of positive end expiratory pressure and tidal volume that was associated with decreased risk of pulmonary complications.

Conclusions:

In this multicenter retrospective observational analysis of patients undergoing one lung ventilation during thoracic surgery we did not detect an independent association between a low tidal volume lung protective ventilation regimen and a composite of postoperative pulmonary complications.

Introduction

Postoperative pulmonary complications are common and highly morbid, particularly in thoracic surgery patients.1 Previous reports have demonstrated that protective ventilation can improve postoperative pulmonary function and reduce the incidence of complications, but the precise definition of protective ventilation remains elusive. Prospective studies of protective ventilation in surgical patients have often compared groups which differ on the basis of multiple ventilatory variables. These fixed ventilation “bundles” are typically comprised of tidal volume (VT) and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), with or without alveolar recruitment maneuvers.2-7 The optimal combination of tidal volume and PEEP to minimize postoperative pulmonary complications has not yet been defined.

Definitions of protective one lung ventilation emerge from expert opinion, translation of evidence from two lung ventilation in general surgical patients, and a small number of clinical trials.2,6-10 Perioperative studies of protective ventilation typically compare lower tidal volumes and moderate PEEP against higher tidal volumes and minimal PEEP.5-7 Recent work has demonstrated that lower VT in the absence of adequate PEEP may be detrimental to patient outcomes.11,12 While the specific impact of tidal volume is unclear, emerging evidence appears to implicate airway driving pressure, rather than VT or PEEP, as a potential determinant of postoperative pulmonary complication risk.13,14

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database is a well-established, validated national clinical outcomes registry used for peer-reviewed publications and quality improvement.15,16 We sought to leverage this database in combination with the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group (MPOG) database – a repository of machine-captured intraoperative physiologic data including ventilator parameters – to evaluate the association between intraoperative ventilation practices during one lung ventilation and patient outcomes.

The primary aim of this study was to examine the relationship between tidal volume, PEEP and use of a recommended protective ventilation strategy during one lung ventilation with the subsequent development of pulmonary complications in patients undergoing thoracic surgery. The secondary aims were 1) to identify an optimal combination of VT and PEEP which minimized postoperative pulmonary complications when adjusted for known risk factors and 2) to determine whether increased airway pressures during ventilation were associated with adverse outcomes. This study expands upon previous work we and others have reported examining the association between ventilation exposures and postoperative clinical outcomes.5-7,12 Advances in the field attributable to this study derive from several factors including the integration of MPOG and STS Thoracic Surgical databases to produce a large relatively homogeneous multicenter cohort of lung resection patients and the subsequent detailed study of the individual and combinatorial associations between ventilation variables and clinically relevant outcome measures.

Methods

Approvals

We obtained coordinating center institutional review board (IRB) approval for this observational cohort study (University of Michigan, IRB MED HUM00024166, HUM00033894). Each participating site additionally obtained IRB approval for submission of a limited data set to the MPOG database. The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the IRB at participating centers. This site IRB approval includes provision for submission of Society of Thoracic Surgeons registry data to MPOG from each center. In keeping with the MPOG bylaws, this study protocol was presented to the MPOG Perioperative Clinical Research Committee and was approved on March 28th, 2017. Following data acquisition an unanticipated imbalance between the protective vs non-protective cohorts was discovered. We revised the protocol twice to address this as well as unmeasured confounding caused by excess population heterogeneity. The plan for statistical analysis was revised, circulated, and approved by Perioperative Clinical Research Committee on July 11th, 2018 and January 29th, 2020. After approval, a data analysis and statistical plan was written and filed with a private entity (MPOG Perioperative Research Committee) before data were accessed or revised analysis conducted. (Supplemental Digital Content 1). During the peer-review process, additional changes as requested by editors were incorporated. Final methods are presented below. We followed the STROBE checklist in developing this manuscript.

Data source, Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The MPOG database, as well as methods for data entry, validation and quality assurance have been previously described17 and have been used for multiple published observational studies.18,19 MPOG data is drawn from cases documented in the Electronic Health Record at participating sites. These data are extracted, standardized, joined to additional laboratory, billing and diagnosis coding data, and de-identified with the exception of date of service, producing a limited dataset.

Five large academic medical centers which submit Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database and MPOG data were included in this study. The Thoracic Surgery Database is managed by each site and uses standard definitions and data elements captured by the data collection form (https://www.sts.org/registries-research-center/sts-national-database/general-thoracic-surgery-database/data-collection).

Data are gathered and aggregated by trained data managers who review medical records of patients undergoing surgical procedures by participating thoracic surgeons at each institution to capture demographics, comorbidities, details of preoperative evaluation, intraoperative course, and postoperative outcomes. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons training manual is the common reference for all data managers who receive annual training at the Advances in Quality Outcomes Seminar hosted by the Society (https://www.sts.org/meetings/calendar-of-events/advances-quality-outcomes-data-managers-meeting). These data are externally and independently audited and is known to be greater than 95% accurate.20

Thoracic Surgery Database records were linked to MPOG records using patient level identifiers at each participating site. These identifiers were removed prior to data upload to the MPOG Coordinating Center (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). At the Coordinating Center, the patient-matched records from both databases were linked using case start date and time.

Patients undergoing one lung ventilation between 01/01/2012 and 12/31/2016 for pneumonectomy, bilobectomy, lobectomy, segmentectomy, or wedge resection/metastasectomy with available General Thoracic Surgery Database and MPOG records were included. We had originally intended to include procedures through 5/31/2017, but data was not available across all sites for this time period and thus the study period was restricted to 12/31/2016. Time of one lung ventilation initiation and termination (where available) was defined based on use of a structured data element in the anesthesia record. Cases were excluded if one lung ventilation was used for less than 15 minutes, if either height or weight data were unavailable, if lung transplantation was performed, or if surgery represented a reoperation within 30 days of a prior included surgery.

Protective Ventilation and other Respiratory Parameter Exposure Variables

Values of tidal volume (VT), PEEP, airway pressures (mean, peak (PMAX) and plateau pressures), end tidal carbon dioxide concentration (ETCO2), fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2), respiratory rate and calculated modified driving pressure (PMAX –PEEP) were derived for use in this study. These variables are stored in the MPOG database at 1-minute intervals. Consistent with our prior work we used a sampling methodology for evaluation of ventilation parameters.18,19 We calculated the median value for the time period 5-15 minutes after the time-stamped documentation of initiation of one lung ventilation for each case.

Criteria for protective ventilation were based upon expert opinion and guidelines for optimal practice during one lung ventilation.8-10 Cases were considered to have been conducted with protective ventilation only if both of the following criteria were met: median tidal volume was ≤ 5 ml/kg predicted body weight and median PEEP ≥ 5 cm H2O. Ventilation variables were subsequently expressed and analyzed as means of the individual case median values.

Modified driving pressure was used as a surrogate of driving pressure in this investigation, since plateau airway pressure data, required for the calculation of driving pressure, was not available from all participating institutions. This modification of driving pressure has been previously reported.21

Patient and procedure variables

In construction of the statistical models used in this manuscript we included data from the MPOG and Thoracic Surgery databases (Appendix 1).

From the MPOG Database: institution, presence of blood product transfusion (as a binary variable), fluid balance (volume of input [crystalloids + colloids + blood products] - volume of fluid output [urine + gastric tube output + estimated blood loss + chest tube] as documented on the anesthetic record) and ASA Physical Status.

From the General Thoracic Surgery Database: forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), presence of missing FEV data, preoperative renal dysfunction, preoperative steroid therapy, Zubrod Performance Classification score, current smoking status, preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiation, major preoperative comorbidity (defined as coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, or diabetes). Procedure type was categorized as: pneumonectomy, bilobectomy, lobectomy, segmentectomy, or wedge resection/metastasectomy (which acted as the reference value in our models). Additionally, we classified surgical approach: thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (which acted as the reference value in our models).

Demographic variables for age, sex, and body mass index were preferentially extracted from the General Thoracic Surgery Database; however if not available or invalid they were derived from the MPOG database.

Outcomes of Interest

The primary outcome was a composite of major postoperative pulmonary complications drawn from the General Thoracic Surgery Database. Pulmonary complications were defined as one or more of the following: initial ventilator support greater than 48 hours, reintubation, pneumonia, atelectasis requiring bronchoscopy, ARDS, air leak greater than 5 days, bronchopleural fistula, respiratory failure, tracheostomy, pulmonary embolism or empyema requiring treatment. Two progressively more comprehensive secondary outcomes were 1) major morbidity - pulmonary complications (as defined above) OR one or more of: unexpected return to the operating room (during same hospital stay), atrial or ventricular dysrhythmias requiring treatment, myocardial infarction, sepsis, renal failure, central neurologic event, unexpected ICU admission, or anastomotic leak and 2) major morbidity (defined above) and/or mortality. All outcomes were drawn from the General Thoracic Surgery Database record and followed the definitions at time of data entry (https://www.sts.org/registries-research-center/sts-national-database/general-thoracic-surgery-database/data-collection).

Statistical Analysis

A complete case analysis was conducted. Data were presented as means with standard deviations or frequencies with percentages. Univariate comparisons between groups were assessed using Pearson Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data and Student’s t or Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous variables, as appropriate. Absolute standardized difference percentages are reported.

The final statistical analysis plan included the use of propensity score matching to adjust for differences between the protective and non-protective ventilation groups. A non-parsimonious regression model was used to estimate each participant’s propensity to receive the protective ventilation exposure. The propensity score model contained: age, sex, body mass index, FEV1, presence of missing FEV data, ASA status, preoperative renal dysfunction, preoperative steroid therapy, Zubrod score, current smoking status, preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiation, institution, and major preoperative comorbidity. Protective ventilation patients were propensity-score matched 1:1 to those not receiving protective ventilation using the “onetomanymtch” greedy matching algorithm.22 Residual covariate imbalance after the match was assessed by computing standardized differences. Variables with an absolute standardized difference <10% were considered a strong match. Within the matched cohort, univariate differences between those with and without protective ventilation were assessed using McNemar’s test for categorical variables and paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for continuous variables, as appropriate.

Before regression models were constructed, all variables under consideration for model inclusion were assessed for collinearity using the condition index. If the condition index was > 30, a Pearson’s correlation matrix was developed. Those variable pairs with a correlation of >= 0.70 were combined into a single concept, or the variable with the larger univariate effect size was selected for inclusion. All other variables were considered fit for model entry.

To evaluate the primary aim in the matched cohort, a conditional logistic regression model was used to assess the relationship between protective ventilation status and outcome with the covariates of blood product transfusion, fluid balance, surgical procedure (wedge resection, segmentectomy, lobectomy, bilobectomy, pneumonectomy) and surgical approach (VATS vs Open). Measures of effect for model covariates were reported as conditional adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The model predictive capability was reported using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve c-statistic. Any covariate found to be statistically significant was considered an independent predictor of the outcome of interest. These models were also constructed for the secondary outcomes (morbidity; morbidity and mortality).

The full study cohort was used for analysis of optimal VT and PEEP combinations and examination for any relationship between airway pressures and outcome. Traditional logistic regression models were used for these analyses. Measures of effect for model covariates were reported for logistic regression as adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Any covariate found to be statistically significant after adjustment was considered an independent predictor of the outcome of interest.

To assess if an alternative combination of VT and PEEP was associated with a lower risk of pulmonary complications, a matrix of adjusted odds ratios was constructed with the reference category of VT between 4 and 6 ml/kg predicted body weight and PEEP between 4 and 6 cm H2O.

To assess if modified driving pressure was associated with primary or secondary outcomes 3 multivariable logistic regression models were constructed, adjusted for the covariates specified above. A similar analysis was conducted for PMAX.

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SPSS 24 (IBM Corp.). Two-tailed hypothesis testing was conducted and a p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. Additional information regarding aim-specific analyses can be found in Appendix 2.

Power Analysis

An a priori sample size calculation was performed using a two-sided Z test with un-pooled variance. A sample size of 1315 unmatched cases in each group (total study N = 2630) provided 90% power at an alpha = 0.05 to detect a 5% difference (deemed to represent a clinically significant difference) in the rate of pulmonary complications, assuming a 22% rate of events in the non-protective ventilation group.

Results

Study Populations and Outcomes Experienced

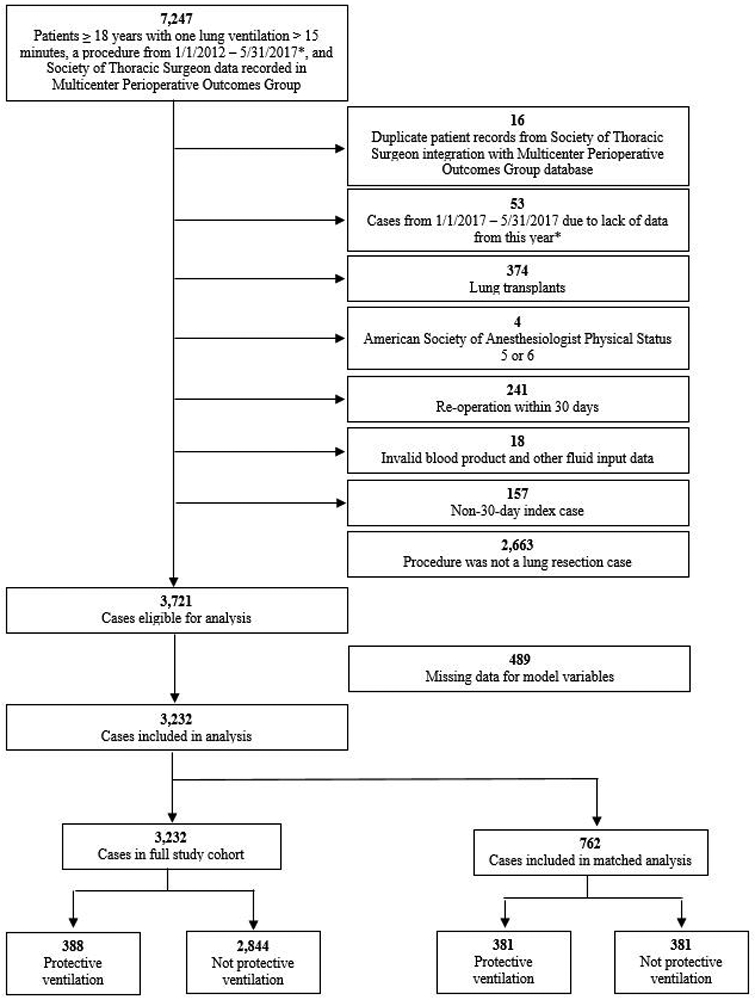

Of 3721 cases which were eligible for analysis, 489 were excluded for missing data required for model construction. A total of 3,232 cases from 5 institutions were available for the final analysis (Figure 1). Baseline cohort characteristics are shown in Table 1. It should be noted that some cases from one institution have been previously reported (693 cases from 2012-2014; 194 cases which are included in the current matched cohort).12

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through study.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and demographics for the full study cohort population and the matched study population

| Full Study Cohort Population | Matched Population | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Protective Ventilation (N = 2,844) |

Protective Ventilation (N = 388) |

Absolute Standardized Difference (%) |

P- Value |

No Protective Ventilation (N = 381) |

Protective Ventilation (N = 381) |

Absolute Standardized Difference (%) |

P- Value |

|

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age | 62.6(12.4) | 62(13.6) | 5.2 | 0.351 | 61.6(13.8) | 62.3(13.3) | 5 | 0.491 |

| Female Sex | 1,577 (55.5) | 138 (35.6) | 40.7 | <0.001 | 140 (36.8) | 136 (35.7) | 2.2 | 0.763 |

| Body Mass Index | 28.5(6.5) | 27.6(6.8) | 13.2 | 0.014 | 28(5.7) | 27.6(6.7) | 6.7 | 0.354 |

| ASA Class 3 or higher | 2,217 (78.0) | 308 (79.4) | 3.5 | 0.523 | 307 (80.6) | 301 (79.0) | 3.9 | 0.589 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| COPD | 671 (23.6) | 90 (23.2) | 1 | 0.857 | 90 (23.6) | 88 (23.1) | 1.2 | 0.862 |

| Congestive Heart Failure* | 81 (4.7) | 22 (7.1) | 10.2 | 0.121 | 16 (5.1) | 19 (6.3) | 4.8 | 0.548 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 427 (15.0) | 67 (17.3) | 6.1 | 0.247 | 66 (17.3) | 66 (17.3) | 0 | 0.999 |

| Cerebrovascular History | 5.9 | 0.304 | 5.8 | 0.421 | ||||

| Transient ischemic attack | 74 (2.6) | 12 (3.1) | 12 (3.2) | 12 (3.2) | ||||

| Cerebrovascular accident | 65 (2.3) | 12 (3.1) | 8 (2.1) | 12 (3.2) | ||||

| Diabetes | 449 (15.8) | 60 (15.5) | 0.9 | 0.870 | 57 (15.0) | 60 (15.8) | 2.2 | 0.763 |

| Dialysis | 14 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 3.5 | 0.545 | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 0 | 0.999 |

| Hypertension | 1,547 (54.4) | 193 (49.7) | 9.3 | 0.085 | 213 (55.9) | 191 (50.1) | 11.6 | 0.111 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease* | 101 (5.8) | 14 (4.5) | 6 | 0.309 | 19 (6.1) | 14 (4.6) | 6.6 | 0.413 |

| Prior Cardiothoracic Surgery | 420 (14.8) | 66 (17.0) | 6.1 | 0.247 | 61 (16.0) | 64 (16.8) | 2.1 | 0.770 |

| Pulmonary Hypertension | 24 (0.8) | 5 (1.3) | 22.2 | <0.001 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.1) | 2.6 | N/A |

| Smoking | 8.9 | 0.100 | 4.8 | 0.506 | ||||

| Never Smoked | 757 (26.6) | 115 (29.6) | 118 (31.0) | 111 (29.1) | ||||

| Past Smoker (>1 month) | 1,565 (55.0) | 213 (54.9) | 209 (54.9) | 211 (55.4) | ||||

| Current Smoker | 522 (18.4) | 60 (15.5) | 54 (14.2) | 59 (15.5) | ||||

| Major Preoperative Comorbidity | 817 (28.7) | 109 (28.1) | 1.4 | 0.795 | 113 (29.7) | 108 (28.4) | 2.9 | 0.690 |

| Chemotherapy and/or Radiation within 6 months | 131 (4.6) | 20 (5.2) | 2.5 | 0.631 | 22 (5.8) | 20 (5.3) | 2.3 | 0.751 |

| Renal Dysfunction | 100 (3.5) | 13 (3.4) | 0.9 | 0.868 | 7 (1.8) | 13 (3.4) | 9.9 | 0.174 |

| FEV1 (% Predicted) | 77.0(31.7) | 73.7(33.0) | 10.6 | 0.048 | 74.5(32.8) | 74.6(32.1) | 0.1 | 0.986 |

| Missing FEV1 | 268 (9.4) | 45 (11.6) | 7.1 | 0.206 | 40 (10.5) | 40 (10.5) | 0 | 0.999 |

| Zubrod Scale | 6.5 | 0.257 | 2.8 | 0.699 | ||||

| 0 | 1,270 (44.7) | 174 (44.9) | 182 (47.8) | 174 (45.7) | ||||

| 1 | 1,374 (48.3) | 177 (45.6) | 169 (44.4) | 176 (46.2) | ||||

| 2 | 168 (5.9) | 29 (7.5) | 27 (7.1) | 29 (7.6) | ||||

| 3 | 27 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | ||||

| 4 | 5 (0.2) | 6 (1.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Intraoperative Factors | ||||||||

| Blood Product Use (Y/N)* | 55 (1.9) | 4 (1.0) | 7.5 | 0.117 | 7 (1.8) | 4 (1.1) | 6.6 | 0.363 |

| Fluid Balance | 1311(797.5) | 1185.9(816.6) | 15.5 | 0.004 | 1145.1(757.7) | 1197.8(816) | 6.7 | 0.356 |

| Surgical Duration | 162.8(97.5) | 165.3(102.5) | 2.52 | 0.636 | 173.3(106.9) | 165.6(102) | 7.759 | 0.309 |

| Anesthesia Duration | 247.9(106.4) | 252.6(111.1) | 4.3 | 0.420 | 261.4(117.1) | 252.8(110.8) | 7.51 | 0.300 |

| Surgical Type | ||||||||

| Segmentectomy | 135 (4.8) | 21 (5.4) | 3 | 0.566 | 14 (3.7) | 21 (5.5) | 8.8 | 0.226 |

| Lobectomy | 1,405 (49.4) | 167 (43.0) | 12.8 | 0.019 | 188 (49.3) | 167 (43.8) | 11.1 | 0.128 |

| Bilobectomy | 93 (3.3) | 16 (4.1) | 4.5 | 0.423 | 17 (4.5) | 16 (4.2) | 1.3 | 0.859 |

| Pneumonectomy | 84 (3.0) | 7 (1.8) | 7.5 | 0.125 | 10 (2.6) | 6 (1.6) | 7.3 | 0.313 |

| Wedge Resection | 1,127 (39.6) | 177 (45.6) | 12.1 | 0.024 | 152 (39.9) | 171 (44.9) | 10.1 | 0.164 |

| Surgical Approach | 3.4 | 0.537 | 8.1 | 0.243 | ||||

| Thoracotomy | 805 (28.3) | 104 (26.8) | 116 (30.5) | 102 (26.8) | ||||

| Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | 2,039 (71.7) | 284 (73.2) | 268 (70.0) | 279 (73.2) | ||||

| Median Physiologic Factors For First 5 to 15 Minutes Following Start of One Lung Ventilation | ||||||||

| Respiratory Rate | 12 (2.7) | 14 (3.1) | 63.2 | <0.001 | 12 (2.6) | 14 (3.3) | 57.6 | <0.001 |

| FIO2 % | 89 (12.5) | 89 (13.5) | 2.1 | 0.704 | 89 (12.5) | 88 (13.6) | 4 | 0.588 |

| Mean Inspiratory Pressure | 11 (2.4) | 11 (2.2) | 9.2 | 0.103 | 10 (2.3) | 10 (2.2) | 0.9 | 0.914 |

| Peak Inspiratory Pressure | 24 (5.3) | 23 (5.7) | 31.9 | <0.001 | 24 (5.1) | 23 (5.5) | 30.4 | <0.001 |

| Plateau Pressure | 21 (5) | 21 (5.7) | 18.6 | 0.025 | 21 (5) | 21 (5.4) | 22.4 | 0.049 |

| ETCO2 | 35 (5.3) | 39 (5.8) | 61.9 | <0.001 | 37 (5.1) | 39 (5.7) | 46.3 | <0.001 |

| Tidal Volume/Predicted Body Weight (ml/kg) | 6.7 (1.4) | 4.4 (0.5) | 217.4 | <0.001 | 6.4(1.2) | 4.4(0.5) | 208.4 | <0.001 |

| PEEP (cm H2O) | 5 (1.7) | 6 (1.1) | 67.7 | <0.001 | 5 (1.8) | 6 (1.1) | 65.4 | <0.001 |

| Modified Driving Pressure | 17 (12.5) | 15 (5.1) | 42.6 | <0.001 | 17 (12.5) | 15 (5.4) | 47 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as frequency (percentage) or mean and standard deviation, as appropriate. Full study cohort comparisons were calculated using t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous variables and Chi-Square or Fisher’s Exact tests for categorical variables, as appropriate. Matched population comparisons were calculated using paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for continuous variables and McNemar tests for categorical variables, as appropriate. There were no standardized differences > 10% for matched factors.

Data are presented as percentage of non-missing data

Abbreviations: ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FIO2 = inspired oxygen fraction, PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure, ETCO2 = end-tidal carbon dioxide.

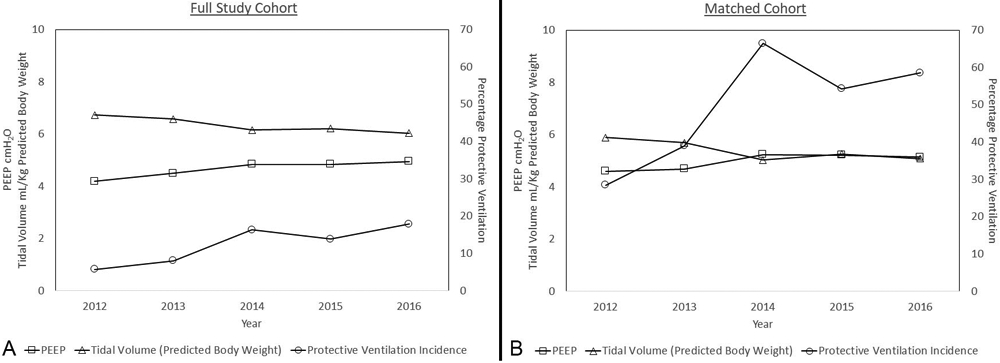

In the unmatched cohort, a primary pulmonary complication outcome occurred in 427 (13.2%) of cases; secondary outcomes - major morbidity and major morbidity and/or mortality - occurred in 659 (20.4%) and 676 (20.9%) cases respectively (Table 2). In 2012 mean VT was 6.7 ml/kg (SD 1.61); in 2016 mean VT was 6.0 (SD 1.25) (p < 0.0001), while mean PEEP was 4 cm H2O (SD 2) in 2012 and 5 cm H2O (SD 2) in 2016 (p < 0.0001) (Table 1; Figure 2). The proportion of cases meeting the definition of lung protective ventilation was 5.7% in 2012 and 17.9% (p < 0.001) in 2016 (Figure 2). The prevalence of the primary outcome and major morbidity did not change significantly during the study period (pulmonary complications - 11.4% to 15.7%, p = 0.147; major morbidity - 18.5% to 22.9%, p = 0.088). However, there was a significant increase in secondary outcome of major morbidity and/or mortality from 2012 to 2016 (18.6% to 23.8%, p = 0.039) (Supplemental Digital Content 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Experienced post-operative outcomes, in the full study cohort and matched cohort

| Full Study Cohort | Matched Cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Protective Ventilation (n = 2,844) |

Protective Ventilation (n = 388) |

P-Value | No Protective Ventilation (n = 381) |

Protective Ventilation (n = 381) |

P-Value | |

| Postoperative Outcomes | ||||||

| 30-Day Pulmonary Complications | 362 (12.7) | 65 (16.8) | 0.028 | 59 (15.5) | 64 (16.8) | 0.615 |

| 30-Day Major Morbidity | 565 (19.9) | 94 (24.2) | 0.046 | 86 (22.6) | 93 (24.4) | 0.544 |

| 30-Day Major Morbidity and/or Mortality | 578 (20.3) | 98 (25.3) | 0.025 | 89 (23.4) | 96 (25.2) | 0.550 |

| Pulmonary Complications | ||||||

| ARDS | 9 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 0.632 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | N/A |

| Air leak > 5 days | 178 (6.3) | 27 (7.0) | 0.596 | 24 (6.3) | 27 (7.1) | 0.662 |

| Atelectasis | 77 (2.7) | 22 (5.7) | 0.002 | 19 (5.0) | 21 (5.5) | 0.739 |

| Bronchopleural Fistula | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Pneumonia | 62 (2.2) | 11 (2.8) | 0.415 | 11 (2.9) | 10 (2.6) | 0.827 |

| Pneumothorax | 60 (2.1) | 10 (2.6) | 0.553 | 18 (4.7) | 10 (2.6) | 0.131 |

| Other pulmonary event | 34 (1.2) | 8 (2.1) | 0.158 | 5 (1.3) | 8 (2.1) | 0.405 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 12 (0.4) | 4 (1.0) | 0.116 | 3 (0.8) | 4 (1.1) | 0.706 |

| Respiratory failure | 40 (1.4) | 9 (2.3) | 0.180 | 4 (1.1) | 8 (2.1) | 0.248 |

| Tracheostomy | 14 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 0.999 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.999 |

| Ventilator support > 48 hours | 7 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.999 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Morbidity Complications | ||||||

| Return to Operating Room | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Atrial Arrhythmia | 241 (8.5) | 39 (10.1) | 0.300 | 31 (8.1) | 39 (10.2) | 0.302 |

| Ventricular Arrhythmia | 9 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.611 | 5 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Myocardial Infarction | 12 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 0.681 | 4 (1.1) | 2 (0.5) | 0.414 |

| Sepsis | 9 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.999 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.999 |

| Renal Failure | 9 (0.3) | 3 (0.8) | 0.167 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 0.564 |

| Central Neurological Event | 8 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.999 | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 0.564 |

| Unexpected ICU Admission | 66 (2.3) | 11 (2.8) | 0.533 | 11 (2.9) | 11 (2.9) | 0.999 |

| Anastomic Leak | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A |

| Any morbidity | 303 (10.7) | 50 (12.9) | 0.186 | 42 (11.0) | 49 (12.9) | 0.425 |

| Mortality Complications | ||||||

| 30-Day Mortality | 27 (1.0) | 6 (1.6) | 0.277 | 3 (0.8) | 5 (1.3) | 0.480 |

Data are presented as frequency (percentage) or median with 25th and 75th percentiles, as appropriate. Pre-match population comparisons calculated using Chi-Square or Fisher’s Exact tests for categorical variables, as appropriate. Matched population comparisons were calculated using McNemar tests for categorical variables.

Abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, ICU = intensive care unit.

Figure 2.

Mean Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) in centimeters of water (cm H2O), Mean Tidal Volume milliliters per kilogram of weight by predicted body weight and Percentage of Cases Meeting Protective Ventilation criteria over time by study year.

Primary Aim: Relationship Between Protective Ventilation and Outcome

Propensity score matching addressed differences between the baseline characteristics of the protective and non-protective ventilation populations (Table 1). Of the 388 cases which met the protective ventilation definition, 381 (98.2%) were propensity score matched to non-protective ventilation cases, resulting in a primary aim study population of 762 patients. In our conditional logistic regression model, protective ventilation was not found to be associated with differential risk of pulmonary complications (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR]: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.56, 1.32; p = 0.480), major morbidity (AOR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.55, 1.19; p = 0.283) or morbidity and mortality (AOR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.55, 1.19; p = 0.281).

Secondary Aim: Exploration of an alternative definition of lung protective ventilation

Given the lack of association between this definition of protective ventilation and outcome we attempted to derive an alternative definition of protective ventilation associated with lower risk for pulmonary complications. We used a matrix of odds ratios to determine if an alternative combination of VT and PEEP were associated with a lower risk of pulmonary complications. We did not find a combination of these parameters that predicted a lower risk of pulmonary complications compared to the reference definition (data not shown). When VT or PEEP were analyzed in isolation as categorical ranges – per 1 ml/kg for VT and 1 cm H2O for PEEP - we found no significant relationship with predicted probability of pulmonary complications (Supplemental Digital Content 4 and 5).

Secondary Aim: Relationship between airway pressures and patient outcome

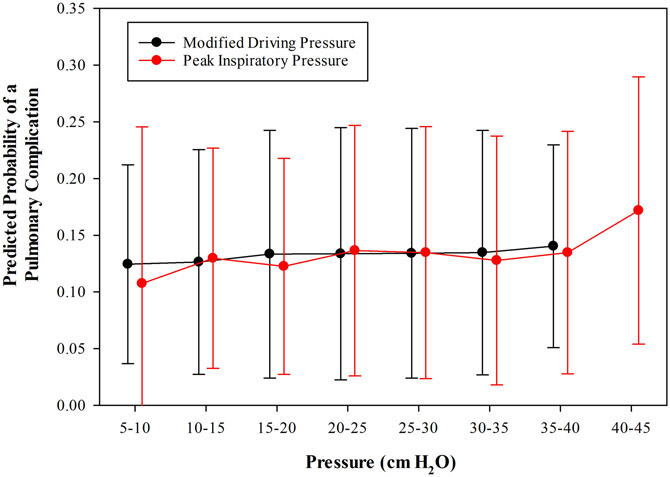

Consistent with prior work, modified airway driving pressure was used as a proxy for airway driving pressure. Using the subjects for which both values were available, we plotted the relationship between them (Supplemental Digital Content 6). The correlation between modified airway driving pressure and airway driving pressure was 0.87 (95% CI: 0.86, 0.88; p < 0.001). In multivariable regression models, neither modified airway driving pressure nor PMAX were associated with a significant increase in the odds of pulmonary complications for each 5 cm H2O increase in pressure (modified airway driving pressure AOR: 0.93, 95% CI 0.84, 1.04, p = 0.145; PMAX AOR: 0.94, 95% CI 0.85, 1.05, p = 0.304 – Supplemental Digital Content 7, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean and 95% confidence interval predictive probability of pulmonary complications by modified driving pressure and peak inspiratory pressure (cm H2O). Pressure was analyzed in five-unit increments.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the relationship between ventilation variables – including VT, PEEP and airway pressures and the subsequent development of postoperative complications in patients undergoing one lung ventilation for thoracic surgery. We draw several conclusions: First, use of recommended ventilation parameters increased during the study period. Second, this definition of protective ventilation was not independently associated with a lower prevalence of pulmonary complications. Third, the development of postoperative complications was not associated with either modified driving pressure or PMAX.

Association of a conventional definition of protective ventilation and outcome

The use of a conventional definition of protective one lung ventilation was not associated with a difference in the prevalence of pulmonary complications (primary outcome), major morbidity or major morbidity and/or mortality (secondary outcomes) between protective and non-protective ventilation subcohorts after propensity score adjustment for population differences. Our study demonstrates a practice trend of increasing use of recommended protective ventilation parameters consistent with that from previous reports.18,19,23 Despite the decrease in VT (6.7 ml/kg predicted body weight to 6.0 ml/kg predicted body weight), and an increase in use of protective ventilation, the prevalence of pulmonary complications and major morbidity did not change significantly during the study period. However, there was a significant increase in the prevalence of major morbidity and/or mortality from 2012 to 2016 (18.6% to 23.8%, p = 0.039) (Supplemental Digital Content 2 and 3).

Our chosen target values for tidal volume (5 ml/kg predicted body weight) and PEEP (5 cm H2O) in the definition of protective one lung ventilation are based on published expert opinion.8-10 Although, these parameters are generally considered to be “protective”, the former reflects a supraphysiologic VT and the latter (PEEP) may be insufficient to maintain an open lung state which prevents atelectasis and atelectrauma during one lung ventilation.24,25 The notion that low VT in the setting of low PEEP is not intrinsically protective is supported by the previously demonstrated inverse relationship 11,12 or lack of relationship26 between VT and the risk of adverse outcomes in both two- and one- lung ventilation surgical settings.

These findings are consistent with results of trials which have evaluated putative protective regimens, combining lower tidal volumes and higher levels of PEEP compared to conventional regimens combining supraphysiologic tidal volumes with minimal PEEP.2,4-7 Such protective regimens may minimize both volutrauma and atelectrauma by limiting distending stress and volume loss/atelectasis respectively, and has been demonstrated to decrease airway driving pressure and mechanical energy delivery.27,28 In a meta-analysis of multiple protective ventilation trials, protective ventilation differed from conventional ventilation most markedly on the basis of PEEP (> 6 fold difference), whereas “protective” VT was only 32% lower than that of the conventional groups.29 Thus the primary difference between protective and conventional ventilation may be the use of an open lung strategy which includes sufficient PEEP to minimize volume loss, atelectasis, and the risk of atelectrauma rather than lower VT per se. This view is further supported by recent trials which demonstrated no outcome improvements in patients randomized to receive lower VT.30,31

In our analysis, the primary outcome is a composite of 11 distinct postoperative pulmonary complications, rather than a single outcome more directly related to lung injury, e.g. ARDS. It should be noted that the individual outcome events contributing to a composite outcome vary greatly on the basis of severity (i.e. ARDS vs atelectasis) and frequency (range: 0.3% to 3.1%). Despite its multicenter design and relatively large sample size, our study did not have sufficient power to determine if specific outcome events were associated with different VT and PEEP combinations.

Relationship of Driving Pressure and Outcome

Prior studies have demonstrated an association between airway driving pressure and complications in patients ventilated for ARDS and surgery, though very little information is available for procedures involving one lung ventilation.13,14 In the present study we found that neither modified driving pressure nor PMAX were associated with significantly increased odds of pulmonary complications when analyzed as continuous variables in fixed effects logistic regression models controlling for other risk predictors. These findings are not consistent with those of prior studies.12,13

The current study differs with regard to the use of a surrogate measure - modified driving pressure (PMAX – PEEP). Despite being shown to predict ARDS in a large cohort of general surgical patients its specific utility as a predictor of pulmonary complications in a thoracic surgical population receiving one lung ventilation is not yet established.21 Despite its very close correlation with driving pressure (0.87 (95% CI: 0.86, 0.88; p < 0.001) it is conceivable that this modification is less useful than driving pressure as a surrogate marker of dynamic strain. It is also conceivable that the dramatic elevation of lung elastance associated with one lung ventilation in the lateral position could confound the relationship between airway driving pressure and dynamic strain.32 Finally, it is also possible that the contribution to the overall postoperative pulmonary complication rate from specific pulmonary complications emerging from elevated dynamic strain (e.g. ARDS) is dwarfed by complications from other injurious processes (e.g. atelectasis).

Park et al. recently reported a randomized trial of thoracic surgical patients who were randomized to receive one lung ventilation (VT 6 ml/kg) with either fixed PEEP 5 cm H2O or an individualized PEEP based on an increment trial to the lowest driving pressure.14 In this study, PEEP titration was associated with a reduction in the incidence of pulmonary complications from 12.2% to 5.5%. However, both the delivered PEEP (5 vs. 3 cm H2O) and resultant driving pressure (10 vs. 9 cm H2O) differences between groups were small. The contribution of driving pressure, if any, to the observed findings remains unclear.

Limitations

Although intraoperative ventilation exposures from the MPOG database are detailed and accurate, available data is limited by relative practice homogeneity in ventilation management during the study period. While tidal volume differences between groups are similar to that seen in modern protective ventilation trials,29 the smaller difference in PEEP between the protective and non-protective groups may be insufficient to elicit detectable differences in outcome.

Although recruitment maneuvers have been advocated by some authors as a component of protective ventilation8,9 they were not included in our definition for two reasons. First, recruitment maneuvers cannot be accurately derived from physiologic data with one-minute temporal resolution. Second, there are no evidence-based standardized criteria for their use. Recruitment maneuvers represent a heterogeneous group of practices. Further, they neither constitute a universal feature of protective ventilation nor are they required for the outcome benefits5-7 or necessarily to maintain an open lung state avoiding atelectasis.25,33 Further, they may have the potential to cause harm34,35 and recent guidelines for protective one lung ventilation do not unambiguously support their use10. While our study did not include them and is unable to account for them, the possibility that recruitment maneuvers contribute to the variance in patient outcome remains and may need to be addressed in future work.

We were not able to assess changes in ventilation management which may have occurred during the course of the anesthetic in response to hypoxemia because our sampling methodology focused on the start of one lung ventilation. We have previously demonstrated that the ventilator data from this early period very closely matches that used for the entire period of one lung ventilation.19 Furthermore, hypoxemia typically occurs early in the one lung ventilation period and is thought to be a very infrequent occurrence in modern thoracic anesthesia practice.36

Finally, included data was derived from five academic medical centers, which exhibited variation in the prevalence of complications. The integration of both MPOG and Thoracic Surgery Databases allowed us to combine the advantages of the automatically gathered, detailed, annotated, dataset from MPOG with the highly accurate and validated outcome data derived from the Thoracic Surgery Database. Limitations of the latter database derive from the fact that participation is voluntary. As participants are typically general thoracic surgeons, results may not be generalizable to that of other surgeons or institutions performing similar procedures. Our approach leverages the advantages and strengths of each data source which improves the validity and generalizability of our findings.

Conclusions

This multicenter study demonstrates an increase in adoption of a ventilation regimen including VT ≤ 5 ml/kg PBW in combination with PEEP > 5 cm H2O during one lung ventilation. However, this lower tidal volume regimen was not associated with reduced odds of major pulmonary complications. Furthermore, in this study cohort, neither increasing PMax or modified airway driving pressure were associated with increased odds of major pulmonary complications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would also like to recognize the following members of the MPOG Perioperative Clinical Research Committee: Robert M. Craft, M.D., Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA and William Hightower, M.D., Department of Anesthesiology, Henry Ford West Bloomfield Hospital, Detroit, MI, USA.

The authors recognize Linda W. Martin M.D., Associate Professor of Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA for her assistance with study design and manuscript review.

The authors recognize Genevieve Bell, B.S., Database Analyst, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA for her help with data acquisition.

The authors recognize the assistance of Graciela Mentz, PhD for her assistance in statistical support during the peer review process.

Funding Statement:

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute for General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32GM103730 (DAC) and by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01HL141701 (MRM).

Additional funding attributed to the participating institutions.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

APPENDIX 1 -. List of Variables Used in the Analysis from MPOG and STS Databases

| MPOG Database | STS Database |

|---|---|

| MPOG_Patient_ID | Race |

| MPOG_Case_ID_String | Smoking status |

| MPOG_Institution_ID | Reoperation |

| Date of surgery | Hypertension |

| Case times | Steroid use |

| Age | Congestive heart failure |

| Sex | Coronary artery disease |

| ASA class | Peripheral vascular disorders |

| Height | Prior cardio-thoracic surgery |

| Weight | Current chemotherapy status |

| BMI | Thoracic radiation therapy and timing |

| WHO BMI Classification | Cerebrovascular history |

| Predicted body weight | Pulmonary hypertension |

| Presence of existing airway | Diabetes and type of control |

| Bronchial blocker used | Dialysis |

| Primary anesthesia CPT code | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Anesthesia and surgical duration | Interstitial fibrosis |

| Fluid totals | Smoking status |

| Total crystalloid equivalents given | FEV1 Percent Predicted |

| Tidal volume | Zubrod scale |

| Respiratory rate | Primary surgical CPT code |

| Positive end expiratory pressure | Intraoperative blood transfusion |

| Peak inspiratory pressure | Postoperative destination |

| Plateau airway pressure | 30-day postoperative status |

| Mean inspiratory pressure | 30-day postoperative morbidity |

| SpO2 | Postop Complication - anastomic leak |

| FiO2 | Postop Complication - unexpected ICU admission |

| EtCO2 | Postop Complication - Central neurological event |

| One-lung and two-lung ventilation start and stop times | Postop Complication - Renal failure |

| Blood product use | Postop Complication - Sepsis |

| Postop Complication - MI | |

| Postop Complication - Atrial arrhythmia | |

| Postop Complication - Ventricular arrhythmia | |

| Postop Complication - Return to OR | |

| Postop Complication - Respiratory failure | |

| Postop Complication - Atelectasis | |

| Postop Complication - Air leak > 5 days | |

| Postop Complication - Pulmonary embolism | |

| Postop Complication - Bronchopleural fistula | |

| Postop Complication - ARDS | |

| Postop Complication - Tracheostomy | |

| Postop Complication - Empyema | |

| Postop Complication - Pneumonia | |

| Postop Complication - DVT | |

| Postop Complication - Pneumothorax | |

| Postop Complication - Ileus | |

| Postop Complication - Surgical site infection | |

| Postop Complication - Sepsis | |

| Postop Complication - Other infection | |

| Postop Complication - Delirium | |

| Postop Complication - Other pulmonary event | |

| Postop Complication - Discharge status | |

| Postop Complication - 30-day readmission | |

| Postop Complication - Ventilator support > 48 hours | |

| Unanticipated surgical conversion | |

| Unanticipated surgical conversion type |

APPENDIX 2. Aim-specific statistical analysis

Aim 1: Assessment of the relationship of ventilator parameters, adherence to suggested lung protective strategy and patient outcome

The matched cohort was used for this analysis. Univariate comparisons between LPV group status and the rate of each outcome was computed using McNemar’s test. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to determine if there was an increase in documented use of LPV over time, where time is defined in quarters.

Aim 2: Derivation of a recommended tidal volume and driving pressure

The full study cohort was used for this analysis. To determine the most beneficial combination of PEEP and tidal volume to reduce pulmonary complications, a matrix of adjusted odds ratios was constructed with the reference category of PEEP between 4 and 6 cmH2O and tidal volume between 4 and 6 ml/kg predicted body weight. The logistic regression model was adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), presence of missing FEV data, ASA status, preoperative renal dysfunction, preoperative steroid therapy, Zubrod score, current smoking status, preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiation, major preoperative comorbidity, institution, presence of blood product transfusion, fluid balance, segmentectomy (vs. wedge resection), lobectomy (vs. wedge resection), bilobectomy (vs. wedge resection) or pneumonectomy (vs. wedge resection), thoracotomy (vs. video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery).

Aim 3: Assessment of the relationship between driving pressure and outcome

The full study cohort was used in this analysis. Two multivariable logistic regression models were constructed as above to evaluate the impact of ventilator parameters on the primary outcome of pulmonary complications. In addition to the previously mentioned covariates, model 1 contained the variable for modified airway driving pressure (per 1 cm H2O). Model 2 contained the variable PMAX. If modified airway driving pressure or PMAX were statistically significant after adjusting for other significant predictors, they were considered independent predictors of pulmonary complications. Similar models were constructed for the secondary outcomes. Non-linear trends were not assessed.

Aim 4: Assessment of Risk Groups for High Driving Pressures

The full study cohort was used in this analysis. To determine whether patients known to be at higher risk for receiving high VT/kg predicted body weight were more likely to be subjected to ventilator regimens associated with higher levels of modified airway driving pressure, three bi-variable linear regression models were constructed for the dependent variable of modified airway driving pressure. The first model contained the fixed effect of body mass index, the second model contained the fixed effect of height (cm), and the third model contained the fixed effect of gender.

Next, three non-parsimonious logistic regression models were constructed to evaluate whether patients known to be at higher risk for receiving high VT were at higher risk of postoperative pulmonary complications. The covariates of body mass index and sex were removed from the model previously specified, to be entered separately. The first model contained the additional fixed effect of body mass index, the second model contained the additional fixed effect of height, and the third model contained the additional fixed effect of gender. A similar set of models was be constructed for all secondary outcomes. If the additional fixed effect for each model was found to be statistically significant, that characteristic was considered an independent predictor of the outcome of interest. If all three were independent predictors, then those at high risk for receiving high VT were said to be at higher risk for postoperative complications.

Appendix 3

Group Collaborators

Patrick J. McCormick, M.D., M. Eng., Assistant Attending, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA

William Peterson, M.D., Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, Sparrow Health System, Lansing, MI, USA

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Colquhoun declares Research Grant Support paid to Institution from Merck & Co. Inc. unrelated to the presented work.

Dr. Kheterpal declares research support paid to institution from Merck & Co., Inc and Apple, Inc both unrelated to the presented work.

Dr. Chang declares travel reimbursement from American Board of Thoracic Surgery, Expert witness fees from defendant attorney and peer review services/reimbursement from Department of Defense, all unrelated to the presented work.

Dr. Schonberger declares research grant support paid to institution from Merck and Co. Incorporated unrelated to the present work.

Dr. Schonberger reports having an equity stake in Johnson and Johnson unrelated to the present work.

Dr. Blank declares research support paid to institution from the Association of University Anesthesiologists unrelated to the presented work.

Prior Presentations: Elements of this work, as preliminary analyses were presented at the IARS Annual Meeting 2018 - Chicago, IL, April 28–May 1, 2018 and Anesthesiology 2018 - San Francisco, CA, Oct 13 - 17, 2018.

Contributor Information

Douglas A. Colquhoun, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Aleda M. Leis, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Amy M. Shanks, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Michael R. Mathis, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Bhiken I. Naik, Departments of Anesthesiology and Neurosurgery, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Marcel E. Durieux, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Sachin Kheterpal, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Nathan L. Pace, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA.

Wanda M. Popescu, Department of Anesthesiology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA.

Robert B. Schonberger, Department of Anesthesiology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA.

Benjamin D. Kozower, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Dustin M. Walters, Department of Surgery, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

Justin D. Blasberg, Section of Thoracic Surgery, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA.

Andrew C. Chang, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Michael F. Aziz, Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Izumi Harukuni, Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Brandon H. Tieu, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Randal S. Blank, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

References

- 1.Serpa Neto A, Hemmes SN, Barbas CS, Beiderlinden M, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Futier E, Hollmann MW, Jaber S, Kozian A, Licker M, Lin WQ, Moine P, Scavonetto F, Schilling T, Selmo G, Severgnini P, Sprung J, Treschan T, Unzueta C, Weingarten TN, Wolthuis EK, Wrigge H, Gama de Abreu M, Pelosi P, Schultz MJ, investigators PN: Incidence of mortality and morbidity related to postoperative lung injury in patients who have undergone abdominal or thoracic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 1007–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Futier E, Constantin JM, Paugam-Burtz C, Pascal J, Eurin M, Neuschwander A, Marret E, Beaussier M, Gutton C, Lefrant JY, Allaouchiche B, Verzilli D, Leone M, De Jong A, Bazin JE, Pereira B, Jaber S, Group IS: A trial of intraoperative low-tidal-volume ventilation in abdominal surgery. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 428–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weingarten TN, Whalen FX, Warner DO, Gajic O, Schears GJ, Snyder MR, Schroeder DR, Sprung J: Comparison of two ventilatory strategies in elderly patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth 2010; 104: 16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Severgnini P, Selmo G, Lanza C, Chiesa A, Frigerio A, Bacuzzi A, Dionigi G, Novario R, Gregoretti C, de Abreu MG, Schultz MJ, Jaber S, Futier E, Chiaranda M, Pelosi P: Protective mechanical ventilation during general anesthesia for open abdominal surgery improves postoperative pulmonary function. Anesthesiology 2013; 118: 1307–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marret E, Cinotti R, Berard L, Piriou V, Jobard J, Barrucand B, Radu D, Jaber S, Bonnet F, and the PPVsg: Protective ventilation during anaesthesia reduces major postoperative complications after lung cancer surgery: A double-blind randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2018; 35: 727–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang M, Ahn HJ, Kim K, Kim JA, Yi CA, Kim MJ, Kim HJ: Does a protective ventilation strategy reduce the risk of pulmonary complications after lung cancer surgery?: a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2011; 139: 530–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen Y, Zhong M, Wu W, Wang H, Feng M, Tan L, Wang Q: The impact of tidal volume on pulmonary complications following minimally invasive esophagectomy: a randomized and controlled study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 146: 1267–73; discussion 1273-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brassard CL, Lohser J, Donati F, Bussieres JS: Step-by-step clinical management of one-lung ventilation: continuing professional development. Can J Anaesth 2014; 61: 1103–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lohser J, Slinger P: Lung Injury After One-Lung Ventilation: A Review of the Pathophysiologic Mechanisms Affecting the Ventilated and the Collapsed Lung. Anesth Analg 2015; 121: 302–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batchelor TJP, Rasburn NJ, Abdelnour-Berchtold E, Brunelli A, Cerfolio RJ, Gonzalez M, Ljungqvist O, Petersen RH, Popescu WM, Slinger PD, Naidu B: Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery: recommendations of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(R)) Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2019; 55: 91–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levin MA, McCormick PJ, Lin HM, Hosseinian L, Fischer GW: Low intraoperative tidal volume ventilation with minimal PEEP is associated with increased mortality. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113: 97–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blank RS, Colquhoun DA, Durieux ME, Kozower BD, McMurry TL, Bender SP, Naik BI: Management of One-lung Ventilation: Impact of Tidal Volume on Complications after Thoracic Surgery. Anesthesiology 2016; 124: 1286–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serpa Neto A, Hemmes SN, Barbas CS, Beiderlinden M, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Futier E, Gajic O, El-Tahan MR, Ghamdi AA, Gunay E, Jaber S, Kokulu S, Kozian A, Licker M, Lin WQ, Maslow AD, Memtsoudis SG, Reis Miranda D, Moine P, Ng T, Paparella D, Ranieri VM, Scavonetto F, Schilling T, Selmo G, Severgnini P, Sprung J, Sundar S, Talmor D, Treschan T, Unzueta C, Weingarten TN, Wolthuis EK, Wrigge H, Amato MB, Costa EL, de Abreu MG, Pelosi P, Schultz MJ, Investigators PN: Association between driving pressure and development of postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation for general anaesthesia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4: 272–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park M, Ahn HJ, Kim JA, Yang M, Heo BY, Choi JW, Kim YR, Lee SH, Jeong H, Choi SJ, Song IS: Driving Pressure during Thoracic Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesthesiology 2019; 130: 385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seder CW, Raymond D, Wright CD, Gaissert HA, Chang AC, Becker S, Puri V, Welsh R, Burfeind W, Fernandez FG, Brown LM, Kozower BD: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database 2018 Update on Outcomes and Quality. Ann Thorac Surg 2018; 105: 1304–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crabtree TD, Gaissert HA, Jacobs JP, Habib RH, Fernandez FG: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database: 2018 Update on Research. Ann Thorac Surg 2018; 106: 1288–1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colquhoun DA, Shanks AM, Kapeles SR, Shah N, Saager L, Vaughn MT, Buehler K, Burns ML, Tremper KK, Freundlich RE, Aziz M, Kheterpal S, Mathis MR: Considerations for Integration of Perioperative Electronic Health Records Across Institutions for Research and Quality Improvement: The Approach Taken by the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group. Anesth Analg 2020; 130: 1133–1146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bender SP, Paganelli WC, Gerety LP, Tharp WG, Shanks AM, Housey M, Blank RS, Colquhoun DA, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Jameson LC, Kheterpal S: Intraoperative Lung-Protective Ventilation Trends and Practice Patterns: A Report from the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group. Anesth Analg 2015; 121: 1231–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colquhoun DA, Naik BI, Durieux ME, Shanks AM, Kheterpal S, Bender SP, Blank RS, Investigators M: Management of 1-Lung Ventilation-Variation and Trends in Clinical Practice: A Report From the Multicenter Perioperative Outcomes Group. Anesth Analg 2018; 126: 495–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magee MJ, Wright CD, McDonald D, Fernandez FG, Kozower BD: External validation of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 96: 1734–9; discussion 1738-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blum JM, Stentz MJ, Dechert R, Jewell E, Engoren M, Rosenberg AL, Park PK: Preoperative and intraoperative predictors of postoperative acute respiratory distress syndrome in a general surgical population. Anesthesiology 2013; 118: 19–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons L: Performing a 1:N Case-Control Match on Propensity Score. , SAS Institute Inc. 2004 Proceedings of the Twenty Nienth Annual SAS® Users Group International Conference. Montréal, Canada, SAS Institute Inc., 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kidane B, Choi S, Fortin D, O'Hare T, Nicolaou G, Badner NH, Inculet RI, Slinger P, Malthaner RA: Use of lung-protective strategies during one-lung ventilation surgery: a multi-institutional survey. Ann Transl Med 2018; 6: 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereira SM, Tucci MR, Morais CCA, Simoes CM, Tonelotto BFF, Pompeo MS, Kay FU, Pelosi P, Vieira JE, Amato MBP: Individual Positive End-expiratory Pressure Settings Optimize Intraoperative Mechanical Ventilation and Reduce Postoperative Atelectasis. Anesthesiology 2018; 129: 1070–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spadaro S, Grasso S, Karbing DS, Fogagnolo A, Contoli M, Bollini G, Ragazzi R, Cinnella G, Verri M, Cavallesco NG, Rees SE, Volta CA: Physiologic Evaluation of Ventilation Perfusion Mismatch and Respiratory Mechanics at Different Positive End-expiratory Pressure in Patients Undergoing Protective One-lung Ventilation. Anesthesiology 2018; 128: 531–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amar D, Zhang H, Pedoto A, Desiderio DP, Shi W, Tan KS: Protective Lung Ventilation and Morbidity After Pulmonary Resection: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Anesth Analg 2017; 125: 190–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collino F, Rapetti F, Vasques F, Maiolo G, Tonetti T, Romitti F, Niewenhuys J, Behnemann T, Camporota L, Hahn G, Reupke V, Holke K, Herrmann P, Duscio E, Cipulli F, Moerer O, Marini JJ, Quintel M, Gattinoni L: Positive End-expiratory Pressure and Mechanical Power. Anesthesiology 2019; 130: 119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrando C, Soro M, Unzueta C, Suarez-Sipmann F, Canet J, Librero J, Pozo N, Peiro S, Llombart A, Leon I, India I, Aldecoa C, Diaz-Cambronero O, Pestana D, Redondo FJ, Garutti I, Balust J, Garcia JI, Ibanez M, Granell M, Rodriguez A, Gallego L, de la Matta M, Gonzalez R, Brunelli A, Garcia J, Rovira L, Barrios F, Torres V, Hernandez S, Gracia E, Gine M, Garcia M, Garcia N, Miguel L, Sanchez S, Pineiro P, Pujol R, Garcia-Del-Valle S, Valdivia J, Hernandez MJ, Padron O, Colas A, Puig J, Azparren G, Tusman G, Villar J, Belda J, Individualized PeRioperative Open-lung VN: Individualised perioperative open-lung approach versus standard protective ventilation in abdominal surgery (iPROVE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6: 193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serpa Neto A, Hemmes SN, Barbas CS, Beiderlinden M, Biehl M, Binnekade JM, Canet J, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Futier E, Gajic O, Hedenstierna G, Hollmann MW, Jaber S, Kozian A, Licker M, Lin WQ, Maslow AD, Memtsoudis SG, Reis Miranda D, Moine P, Ng T, Paparella D, Putensen C, Ranieri M, Scavonetto F, Schilling T, Schmid W, Selmo G, Severgnini P, Sprung J, Sundar S, Talmor D, Treschan T, Unzueta C, Weingarten TN, Wolthuis EK, Wrigge H, Gama de Abreu M, Pelosi P, Schultz MJ, Investigators PN: Protective versus Conventional Ventilation for Surgery: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2015; 123: 66–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karalapillai D, Weinberg L, Peyton P, Ellard L, Hu R, Pearce B, Tan CO, Story D, O'Donnell M, Hamilton P, Oughton C, Galtieri J, Wilson A, Serpa Neto A, Eastwood G, Bellomo R, Jones DA: Effect of Intraoperative Low Tidal Volume vs Conventional Tidal Volume on Postoperative Pulmonary Complications in Patients Undergoing Major Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020; 324: 848–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Writing Group for the PI, Simonis FD, Serpa Neto A, Binnekade JM, Braber A, Bruin KCM, Determann RM, Goekoop GJ, Heidt J, Horn J, Innemee G, de Jonge E, Juffermans NP, Spronk PE, Steuten LM, Tuinman PR, de Wilde RBP, Vriends M, Gama de Abreu M, Pelosi P, Schultz MJ: Effect of a Low vs Intermediate Tidal Volume Strategy on Ventilator-Free Days in Intensive Care Unit Patients Without ARDS: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018; 320: 1872–1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiumello D, Formenti P, Bolgiaghi L, Mistraletti G, Gotti M, Vetrone F, Baisi A, Gattinoni L, Umbrello M: Body Position Alters Mechanical Power and Respiratory Mechanics During Thoracic Surgery. Anesth Analg 2020; 130: 391–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ostberg E, Thorisson A, Enlund M, Zetterstrom H, Hedenstierna G, Edmark L: Positive End-expiratory Pressure Alone Minimizes Atelectasis Formation in Nonabdominal Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 2018; 128: 1117–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Writing Group for the Alveolar Recruitment for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Trial I, Cavalcanti AB, Suzumura EA, Laranjeira LN, Paisani DM, Damiani LP, Guimaraes HP, Romano ER, Regenga MM, Taniguchi LNT, Teixeira C, Pinheiro de Oliveira R, Machado FR, Diaz-Quijano FA, Filho MSA, Maia IS, Caser EB, Filho WO, Borges MC, Martins PA, Matsui M, Ospina-Tascon GA, Giancursi TS, Giraldo-Ramirez ND, Vieira SRR, Assef M, Hasan MS, Szczeklik W, Rios F, Amato MBP, Berwanger O, Ribeiro de Carvalho CR: Effect of Lung Recruitment and Titrated Positive End-Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) vs Low PEEP on Mortality in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017; 318: 1335–1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anaesthesiology PNIftCTNotESo, Hemmes SN, Gama de Abreu M, Pelosi P, Schultz MJ: High versus low positive end-expiratory pressure during general anaesthesia for open abdominal surgery (PROVHILO trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 384: 495–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campos JH, Feider A: Hypoxia During One-Lung Ventilation-A Review and Update. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2018; 32: 2330–2338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.