Abstract

Angiogenesis is a process by which new blood vessels emerge from existing vessels through endothelial cell sprouting, migration, proliferation, and tubule formation. Angiogenesis during skeletal growth, homeostasis and repair is a complex and incompletely understood process. As the skeleton adapts to mechanical loading, we hypothesized that mechanical stimulation regulates the “osteo-angio” crosstalk in the context of angiogenesis. We showed that conditioned media (CM) from osteoblasts exposed to fluid shear stress enhanced endothelial cell proliferation and migration, but not tubule formation, relative to CM from static cultures. Endothelial cell sprouting was studied using a dual-channel collagen gel-based microfluidic device that mimics vessel geometry. Static CM enhanced endothelial cell sprouting frequency, whereas loaded CM significantly enhanced both frequency and length. Both sprouting frequency and length were significantly enhanced in response to factors released from osteoblasts exposed to fluid shear stress in an adjacent channel. Osteoblasts released angiogenic factors, of which osteopontin, PDGF-AA, IGBP-2, MCP-1, and Pentraxin-3 were upregulated in response to mechanical loading. These data suggest that in vivo mechanical forces regulate angiogenesis in bone by modulating “osteo-angio” crosstalk.

Keywords: osteoblast, endothelial cell, angiogenesis, tubule formation, sprouting

Introduction

Bone is a highly vascularized tissue, and the complex vessel network permeating mineralized tissue and bone marrow serves as a conduit through which paracrine and endocrine signals, as well as circulating cells, can access the bone microenvironment.1, 2 Angiogenesis, the process by which new vessels form from existing vessels3, is critical for normal skeletal development, homeostasis, and repair.4 In traumatic fracture5, as well as in the more controlled healing in distraction osteogenesis6, angiogenesis is initiated during the early inflammatory phase and persists well into the early reparative phase during bony callus formation.7

There are four stages of angiogenesis beginning with initiation by vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) signaling. In response to high levels of VEGF, endothelial cells express Ang2, which leads to detachment of mural cells, including pericytes, from the lumen wall. Next, a leading endothelial cell, or “tip cell”, probes the environment and extends filopodia in the direction of proangiogenic factors.8 The production of proteolytic enzymes degrades the basement membrane and extra cellular matrix (ECM)9 allowing migration of the tip cell towards increased concentrations of proangiogenic factors. The third step is differentiation of endothelial cells into “stalk cells”, which undergo proliferation and form the lumen of the nascent vessel. Vessel maturation and stabilization is the final step, and involves recruitment of pericytes via platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and deposition of extracellular matrix.10 Production of Ang1 by pericytes promotes pericyte adhesion, tightens endothelial junctions, and stabilizes the vessel.11, 12

Close contact between cells of the osteogenic lineage and endothelial cells suggests reciprocal regulation via cell-cell contact and/or paracrine signaling.13, 14 We believe this interaction is possible and likely is the marrow cavity and on the periosteal surface where osteoblasts and vessels are closely situated.13 Interactions between cells of the osteo- and endothelial lineage have been shown to be critical in bone formation during development and aging.13, 14 In addition, during fracture repair osteoblast precursors and endothelial cells infiltrate and closely co-localize at the fracture site.15 Progenitor cells differentiating down the osteogenic lineage support endothelial migration, tubule formation and sprouting, potentially through VEGF signaling.16 The CXCL12-CXCR4 pathway in Tie-2 positive endothelial progenitor cells is critical in vessel formation during fracture repair.17 In vivo, osteogenic cells express CXCL1218, a stem cell recruitment factor regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1.19 The temporal and spatial expression profiles of CXCL12 in osteogenic cells are also important in angiogenesis and fracture healing20, suggesting that osteolineage cells can directly regulate endothelial cell behavior.

Other angiogenic factors that could be attributed to osteoblasts are osteopontin, platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1), Pentraxin-3, and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-2 (IGFBP-2). Osteopontin supports endothelial cell migration.21 In a multiple myeloma cell line, osteopontin supported angiogenesis.22 PDGF-B is thought to be the principal signal in bone formation, specifically for inducing angiogenesis.23 PDGF-A is found in normally healing fractures and is expressed by osteogenic cells.24 It is also present in rapidly forming bone.25 In this study, PDGF-A was present in the media; and its concentration was sensitive to mechanical stimulation of MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts. MCP-1 plays a key role in angiogenesis by upregulating HIF-1α and VEGF mRNA in endothelial cells.26 The soluble MCP-1 promoted angiogenesis through VEGF release by endothelial cells.27 MCP-1-induced protein promote Tie-2 expression.28 Pentraxin-3 supports tubule formation in vitro; and pentraxin-3 knockout mice exhibit reduced vascular density.29 IGFBP-2 supported HUVEC proliferation, invasion, and tubule formation in vitro; and knockdown of IGFBP-2 reduced CD31-positive cells in vivo.30

The mechanical environment is an important regulator of bone repair31, and the mechanisms by which biophysical stimuli regulate cell signaling and crosstalk between distinct cell lineages, particularly in the context of repair, are incompletely understood. High deformational strains and fluid flow shear stress, likely to exist in the fracture regenerate32 when compliant fixation is used, would act upon resident cells at the fracture site including endothelial cells. In fact, mechanical loading has been shown to significantly impact angiogenesis during fracture repair.33, 34 Initiation of loading after bony bridging of a segmental defect resulted in fewer and larger vessels in the regenerate, and produced beneficial effects on healing.35 However, these studies were not able to distinguish between purely mechanical effects on existing vessels (i.e., vessel rupture) versus mechanically-driven paracrine signals regulating angiogenesis and vessel pruning. Cells of the osteogenic lineage are mechanically sensitive31, 36–48 and their response includes release of angiogenic factors.49, 50 In vitro, both osteoblasts51 and osteocytes48, 52 respond to fluid shear by secreting VEGF.

Molecular mechanisms regulating osteoblast-endothelial cell interactions are incompletely understood. Previous studies focused on release of angiogenic signals from cells at different stages of osteoblast differentiation16; however, less is known about how mechanically-regulated paracrine signals from osteoblasts affect angiogenesis. In this study, we used in vitro methods, an engineered vessel (eVessel) microdevice, and protein array to assess the effects of osteoblast-derived paracrine signals on angiogenesis. We provide evidence that cells of the osteogenic lineage regulate cellular events associated with angiogenesis in an endothelial cell line. We also show that mechanical stimulation enhances release of angiogenic factors from osteoblasts and further regulates endothelial cell behavior.

Material and Methods

Cell culture

The MC3T3-E1 subclone 4 mouse cell line (ATCC) was used as a model of osteoblasts in our studies. MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured in Alpha Minimum Essential Medium with ribonucleosides, deoxyribonucleosides, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate, but without ascorbic acid (Gibco), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (ATCC) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). The C166-GFP cell line was derived from mouse yolk sac (ATCC), is an adherent cell line, and exhibits normal endothelial characteristics. C166-GFP cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (ATCC) with 10% fetal bovine serum (ATCC) and 0.2 mg/ml Geneticin (Gibco). This transgenic endothelial cell line constitutively expresses GFP and high level of fps/fes.53

Conditioned media from mechanically loaded MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts

In vivo, osteoblasts and vessels are situated closely in the bone marrow space. Due to its mechanical complexity, direct measurement of fluid flow in the marrow has not yet been possible. Computational modeling estimated fluid flow induced shear stress in the marrow to be between 0.25 Pa54 and 5 Pa55 under physiological conditions. The highest shear stress is predicted to be at the bone-marrow interface56. The 5 Pa is likely an overestimation, as that model did not account for vascular porosity, which is theorized to relieve interstitial pressure and consequently fluid flow57. To this end, we used a previously published approach to deliver orbital fluid flow shear stress to MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts58 to induce release of mechanically-sensitive proteins into the culture media. The average shear stress of 0.8 Pa and the durations of 2 hr were shown to be stimulatory to osteogenic cells in vitro previously.37, 38, 59

We used conditioned media (CM) from mechanically loaded MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts to assess effects of load-driven paracrine signaling on endothelial cell behavior. MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates at 50,000 cells per well, and incubated for 24 hours with 2 ml media. Plates were placed on an orbital shaker (Thermo Scientific) to induce concentric fluid flow shear stress on cell monolayers. The orbital shaker has a radius of rotation (R) of 10 mm. The density (ρ) of the media was assumed to be 997.3 kg m3. The fluid viscosity (μ) was assumed to be 0.00101 kg m−1 s. The average shear stress (τω) over the well could be calculated as a function of frequency that was shown by Ley et al.60, as follows:

| (1) |

Computational fluid dynamic simulation has confirmed the shear stress level calculated using parameters identical to this study (6-well plates with 2 ml of media) to be in agreement with the analytical solution.58 The rotational frequency was set to 3 Hz, which produced 0.8 Pa of average shear stress at the well surface. Shear loading was applied for 2 hr per day, over 2 days in an incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2, and CM from the mechanically loaded cells (Loaded CM) was collected and immediately frozen at −20°C. Media was also collected and frozen from cells in identical culture conditions but without loading (static conditions, Static CM).

Endothelial cell proliferation

The proliferation of C166-GFP cells was measured by quantifying the number of cells after 12 hours of incubation. The cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at 2,000 cells per well. After 24 hours of incubation, 0.1 ml of static and loaded CM and control media (fresh MC3T3-E1 media, with and without 10 ng/ml VEGF supplement) were added in 1:1 ratio with reduced serum (2.5% FBS) C166-GFP media. VEGF, a proangiogenic factor, was used as a positive control in all of our assays. After 12 hours of incubation, the wells were imaged under bright-field microscopy to obtain three fields of views (1.49 × 1.12 mm). The cells in each field were counted using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Each experimental condition had a sample size of 6. Data are expressed as mean +/− standard deviation for each experimental group.

Endothelial cell migration

A transwell migration assay was used to assess endothelial cell migration. The C166-GFP cells were seeded onto 24-well cell culture inserts containing membranes with 8 μm pores (Corning) at 50,000 cells/insert. The membrane allows for cell migration from the top to the bottom of the insert. Static and Loaded CM, as well as control media (fresh MC3T3-E1 media, with and without 10 ng/ml VEGF supplement) were added to the bottom of the well. Equal volume of C166-GFP media was added to the top of the inserts. The cells were incubated for 4 hours, and then the cells on the topside of the membranes were removed with a cotton swab. The remaining cells on the underside of the membranes were imaged with a fluorescent microscope (Olympus). For each sample, the number of cells was averaged from three fields of view of size 520 × 390 μm. Each experimental condition had a sample size of 6. Data are expressed as mean +/− standard deviation for each experimental group.

Endothelial cell tubule formation

The capability of C166-GFP cells to form tubules (contiguous longitudinal structures formed by cells in close contact) was investigated as described previously.61 Matrigel, Growth Factor Reduced (Corning), was placed in 96-well plates at 20 μl per well, and allowed to polymerize for 30 min at 37°C. The C166-GFP cells were seeded onto Matrigel coated 96-well plates at 20,000 cells per well. Static and loaded CM (0.5 ml) and control media (fresh MC3T3-E1 media, with and without 10 ng/ml VEGF supplement) were added in 1:1 ratio with C166-GFP media to the wells. The cells were incubated for 4 hours to allow for tubule formation. For each sample, 3 fields of view of 1.5 × 1.2 mm were taken with a phase contrast microscope (Zeiss). The total length and number of junctions of the tubule network was quantified using ImageJ. The tubule length was measured by tracing the tubule network (formed by connected tubules of different orientation) with segmented lines. All tubules were counted within each field of view and tubule density is expressed as number of junctions per mm2. The tubule length was normalized to the negative control. Junctions were defined as the intersection of three or more tubules. They were counted in each field of view and normalized to the level from the Static CM. Each experimental condition had a sample size of 3. Data are reported as mean +/− standard deviation for each experimental group.

Microfluidic device mimicking three-dimensional vessel geometry

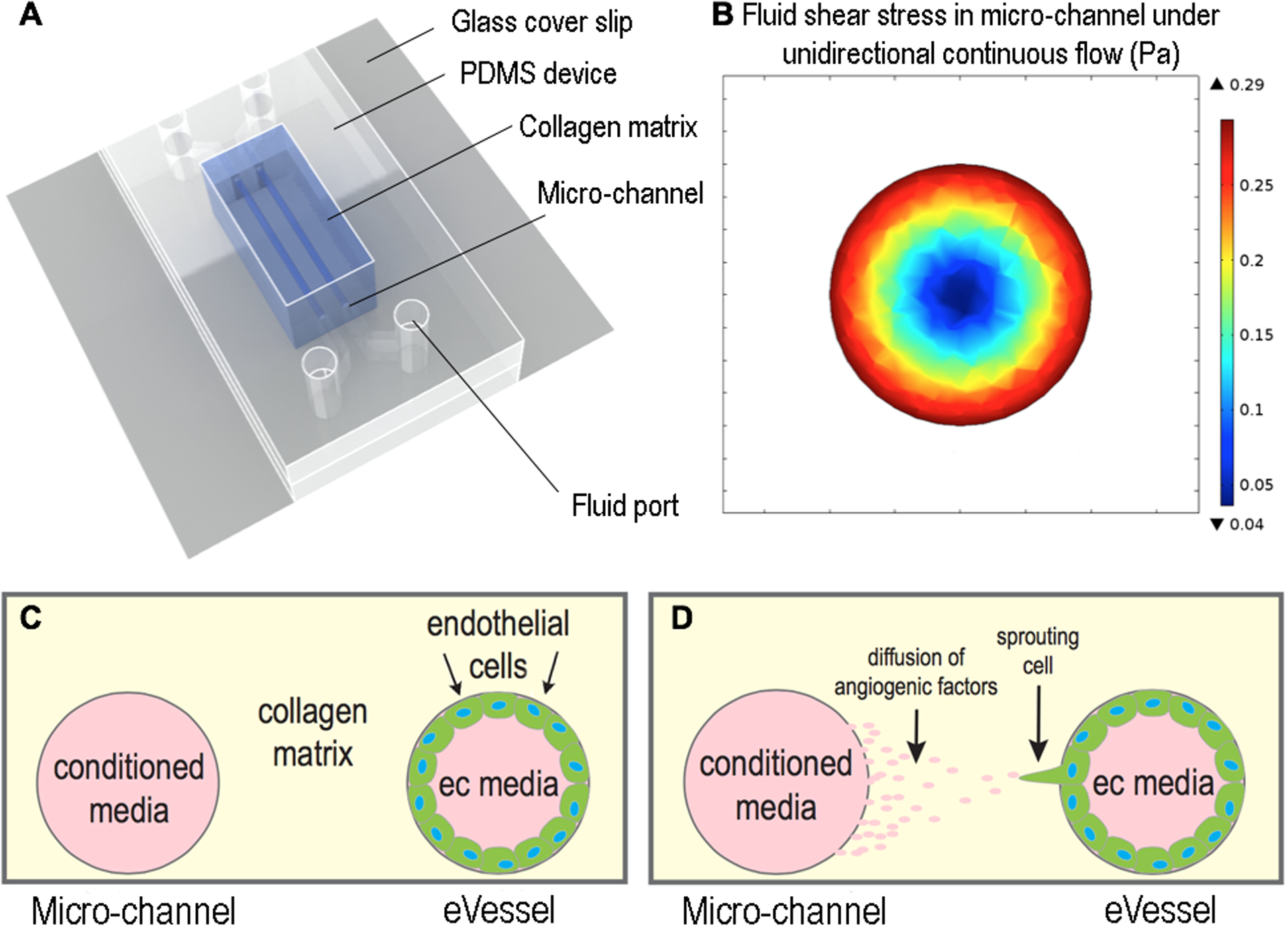

A microfluidic device mimicking vessel geometry (engineered vessel or eVessel) with two parallel cylindrical channels was fabricated as described previously62, 63 and used to assess endothelial cell sprouting. Briefly, a PDMS mold was adhered onto a 25 × 25 mm glass cover slip. Rat-tail type I collagen (Corning) of 3.8 mg/ml was poured into the mold and allowed to polymerize at 37°C for 30 min. Two cylindrical channels were created in the collagen gel with 1 mm separation using acupuncture needles with 400μm diameter (Hwato). The device was covered with C166-GFP media before extracting the needles. (Fig. 1A.) Advantages of this platform are: (1) it mimics the three-dimensional nature of native vessels, (2) three-dimensional cell sprouting can be observed and easily imaged, and (3) the presence of two parallel channels separated by a 1-mm gap of collagen matrix permits diffusion of soluble factors from each channel into the matrix and therefore promotes bidirectional signaling between channels.

Figure 1. Design of a microfluidic engineered vessel (eVEessel) in a collagen matrix that allows diffusion of paracrine signals between two cylindrical channels that support cell culture.

(A) Schematic of the device showing the structures and materials used. (B) Shear stress profile of the fluid in the channel, created using computational fluidic dynamic simulation. Maximum stress of 0.3 Pa occurs at the channel wall, where the cells were attached. (C, D) Schematic showing the hypothesis that soluble angiogenic factors in conditional media would support sprouting of endothelial cells in adjacent channel.

Endothelial cell sprouting regulated by osteoblast-derived conditioned media

To determine the effects of CM on endothelial cell sprouting, C166-GFP endothelial cells were cultured in one channel resulting in a three-dimensional cylindrical vessel (eVessel), and the adjacent channel was filled with CM from MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cells (Static or Loaded), or control media. One channel was filled with C166-GFP cells at a concentration of 107 cells/ml. The device was incubated for 15 min to allow for cell attachment, and then the device was inverted and incubated for an additional 15 min to allow for cell attachment on the opposing channel wall. Non-attached cells were washed away with media. Twenty-four hours later, the adjacent channel was filled with Loaded CM from mechanically loaded MC3T3-E1 cells, as well as control media (fresh MC3T3-E1 media, with and without 10 ng/ml VEGF supplement). The CM in the channel remained static during the experiment. It is expected that the angiogenic factors diffused to the adjacent eVessel channel containing the C166-GFP endothelial cells, and thus regulated endothelial sprouting, as shown previously with supplemented factors.62 The signals would not be replenished by fresh CM during the course of the experiment. The fluid in the eVessel channel containing endothelial cells remained static (no flow). The device was then incubated for 48 hours, and endothelial cell sprouting was quantified in 6–8 regions of 0.5 mm × 0.8 mm along the channel. The experiments had a sample size of 3.

Endothelial cell sprouting regulated directly by osteoblasts

To determine direct effects of osteoblast-derived paracrine signals on endothelial cell sprouting, MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts and C166-GFP endothelial cells were each seeded in separate channels of the microfluidic device as described above. Cells were incubated for 24 hours before the addition of fluid flow through the MC3T3-seeded channel. Devices with MC3T3-E1 cells in static culture were used as controls, and endothelial cell sprouting was measured. Calculated shear stress of 0.3 Pa was applied with 160 μl/min of continuous fluid flow for 15 min per day over 2 days. The shear stress level was calculated by solving the Navier-Stokes equations for the case of a cylindrical pipe in equation (Eqn 2). The resulting wall shear stress (τ = 0.3 Pa) is a function of the fluid viscosity (μ = 0.00101 kg m−1 s), the average fluid velocity (vavg = 15 mm s−1), and the radius of the channel (R = 0.2 mm).

| (2) |

The fluid shear stress at the wall of the channel was further validated using a computational fluid dynamics simulation (Fig. 1B).

For the co-culture experiment in the microfluidic device, a shear stress value of 0.3 Pa was chosen as it is in the range of theoretical values predicted by computational fluid dynamic models54 and have been shown to be stimulatory to osteoblasts .64 We expect osteoblasts to release angiogenic signals throughout the duration of the experiment. The osteoblasts cultured under the same condition, but without flow, were used as controls.

Imaging and quantification of endothelial cell sprouting

Confocal images of the eVessel showing GFP-positive endothelial cells sprouting into the collagen matrix were taken with a Zeiss LSM710 laser scanning confocal microscope at a magnification of 10x. In the z direction, 61 serial images were captured, which covered half of the diameter of the eVessel with a resolution of 11.85 μm per slice. A field of view of 854 × 427 × 723 μm (width × height × depth) was selected for analysis, and the lengths of the sprouts were measured as the distance from the wall of the channel to the end of the tip cell. The sprouting frequency was measured by averaging the number of sprouts per mm of channel length in 8 regions of 0.5 mm × 0.8 mm along the channel. The experiments had a sample size of 3.

Angiogenic signal profile of osteoblast conditioned media

Levels of angiogenic signals in conditioned media from static and loaded MC3T3-E1 cells were measured using the Mouse Angiogenesis Array Kit (R&D Systems) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Conditioned media samples were mixed with biotinylated detection antibodies specific to the signals of interest. Immobilized capture antibodies on a polymer membrane bind to the molecule of interest in conjunction with the detection antibodies. Streptavidin-HRP-conjugated antibodies were then bound to the detection antibodies. Luminol substrate solution was added to produce chemiluminescence that is proportional to the concentration of the bound antibody. The membranes were imaged at 428 nm with chemiluminescence imager (UVP). The luminescence value of each blot was quantified and background subtracted.

Statistics

Data from different experimental groups were compared using unpaired, two-tailed Student t test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. One-way ANOVA and a Tukey post-hoc analysis were used for multiple comparisons for proliferation, migration, and tubule formation experiments. Student T-test was used for eVessel sprouting quantifications.

Results

Enhanced endothelial cell proliferation in response to load-induced signals from osteoblasts

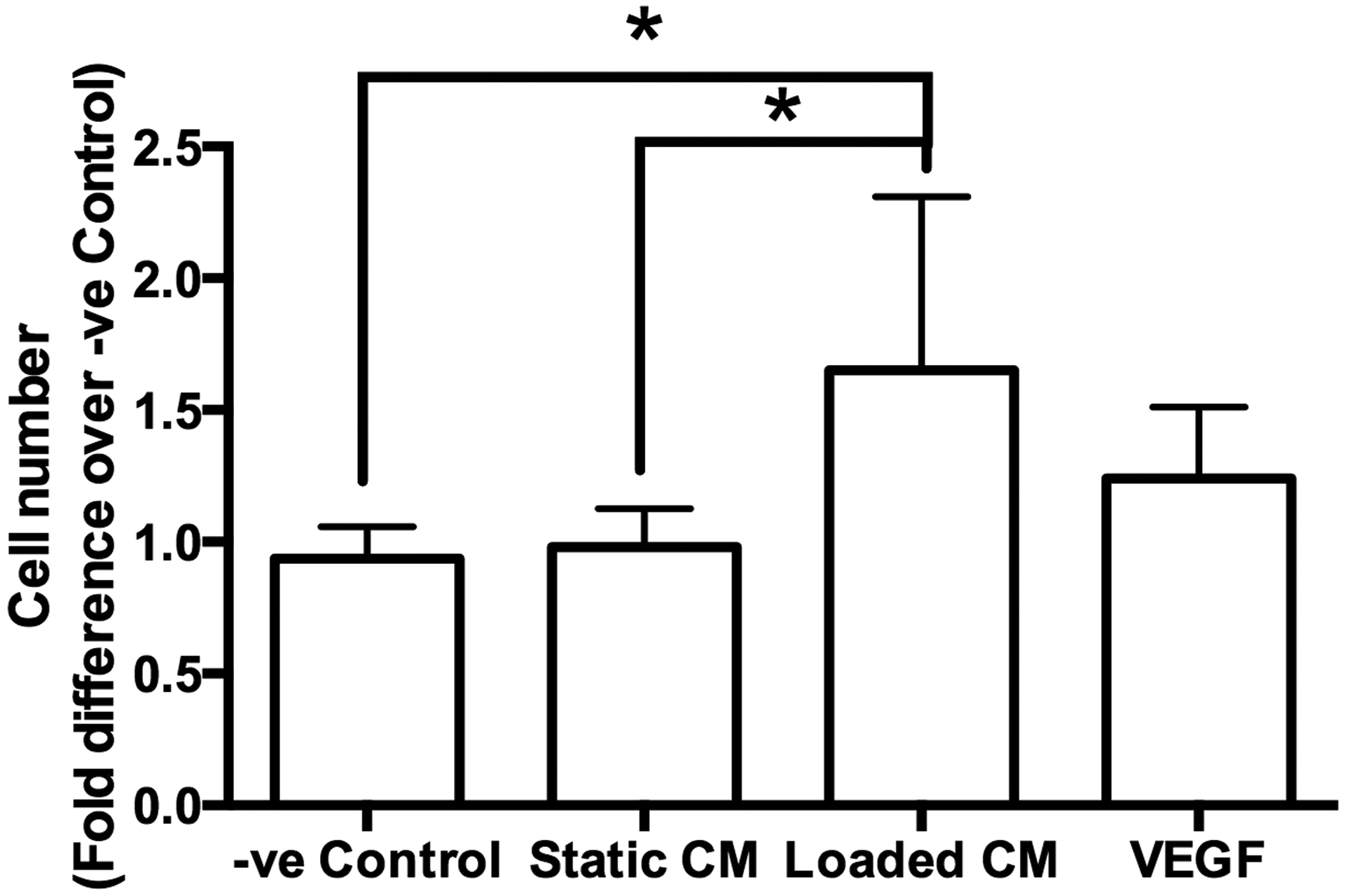

The number of C166-GFP endothelial cells was 1.5-folder greater when cultured with CM from mechanically loaded MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts versus CM from MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts held under static conditions (Fig. 2). Endothelial cell number was not significantly different between the negative control, cells cultured with static CM, and VEGF-treated cells.

Figure 2. Conditioned media from mechanically stimulated osteoblasts induced endothelial cell proliferation.

The cell number of C166-GFP endothelial cells cultured in fresh media (−ve Control), media from statically cultured MC3T3-E1 cells (Static CM), media from mechanically loaded MC3T3-E1 cells (Loaded CM) and VEGF supplemented media. The cell number was normalized to −ve Control. Asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0.05). Data bars indicate mean, n = 6.

Increased endothelial migration in response to load-induced signals from osteoblasts

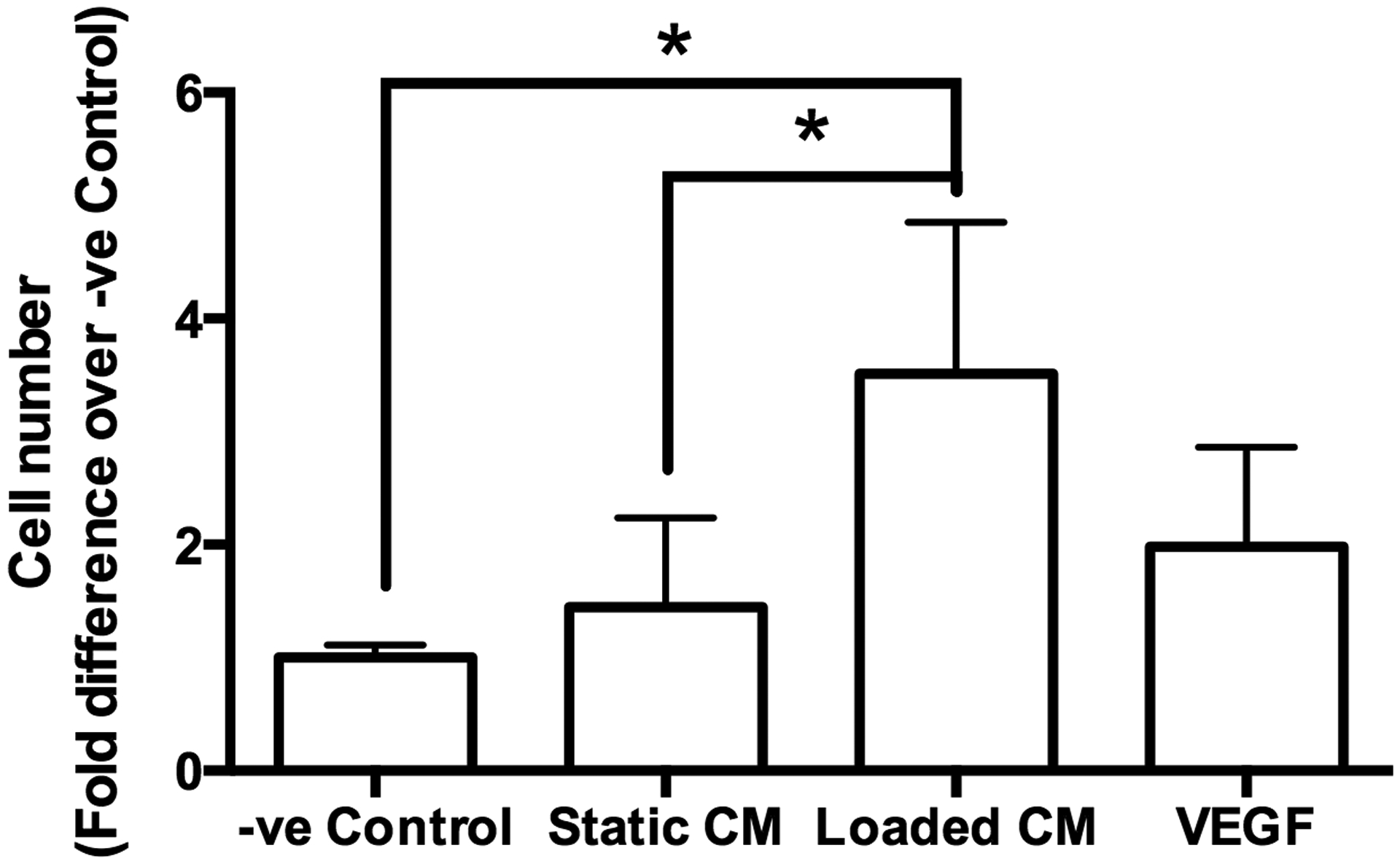

CM from mechanically loaded MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts upregulated endothelial cell migration. CM from mechanically loaded MC3T3-E1 cells induced a significantly higher number of cells to migrate through the insert membrane compared to CM from MC3T3-E1 cells in static culture (Fig. 3). CM from statically cultured MC3T3-E1 cells had no significant effect on the number of migrated cells compared to the fresh media negative control.

Figure 3. Conditioned media from mechanically stimulated osteoblasts induced endothelial cell migration.

Quantification of C166-GFP endothelial cells migrated through a porous (8 μm) membrane in fresh media (−ve Control), media from statically cultured MC3T3-E1 cells (Static CM), and media from mechanically loaded MC3T3-E1 cells (Loaded CM). The number of cells in each group was normalized to −ve Control. Asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0.05). Data bars indicate mean, n = 6.

Tubule formation supported by osteoblast paracrine signaling

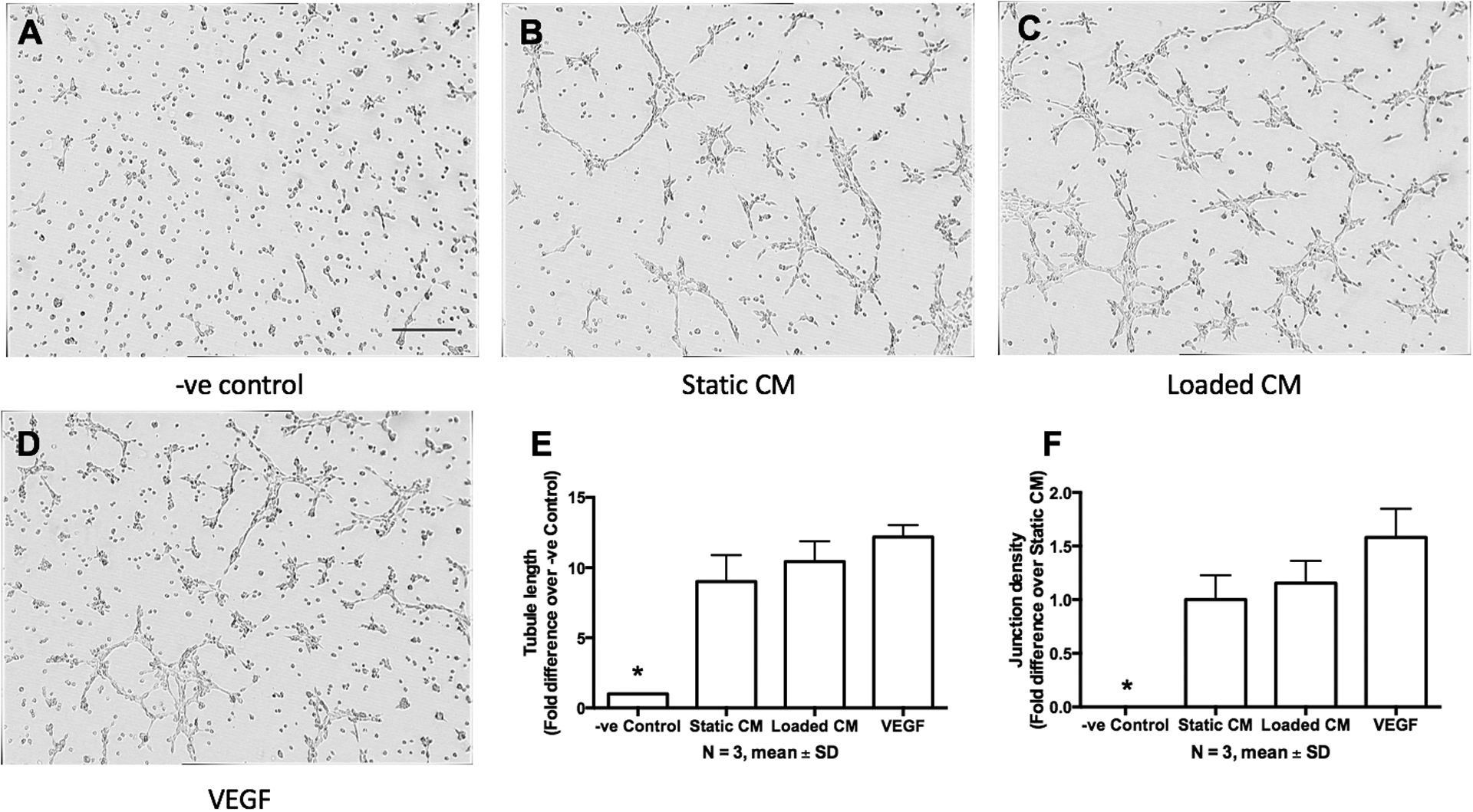

Tubule formation in C166-GFP endothelial cells was significantly increased by static CM, loaded CM, and VEGF treatment, with no difference in tubule length or junction density between these three experimental groups (Fig. 4). Tubule formation was not observed in the negative control.

Figure 4. Conditioned media from osteoblasts induce tubule formation of endothelial cells.

(A) C166-GFP endothelial cells cultured on Matrigel in fresh MC3T3-E1 media, which served as the negative control (−ve control). (B) Tubule formation in conditioned media from statically cultured MC3T3-E1 cells (Static CM). (C) Tubule formation in conditioned media from mechanically loaded MC3T3-E1 cells (Loaded CM). (D) Tubule formation in media supplemented with 10 ng/ml VEGF, which served as positive control. (E) Quantification of cells from A-D. Data bars indicate mean, n = 3. Scale bar = 200 μm.

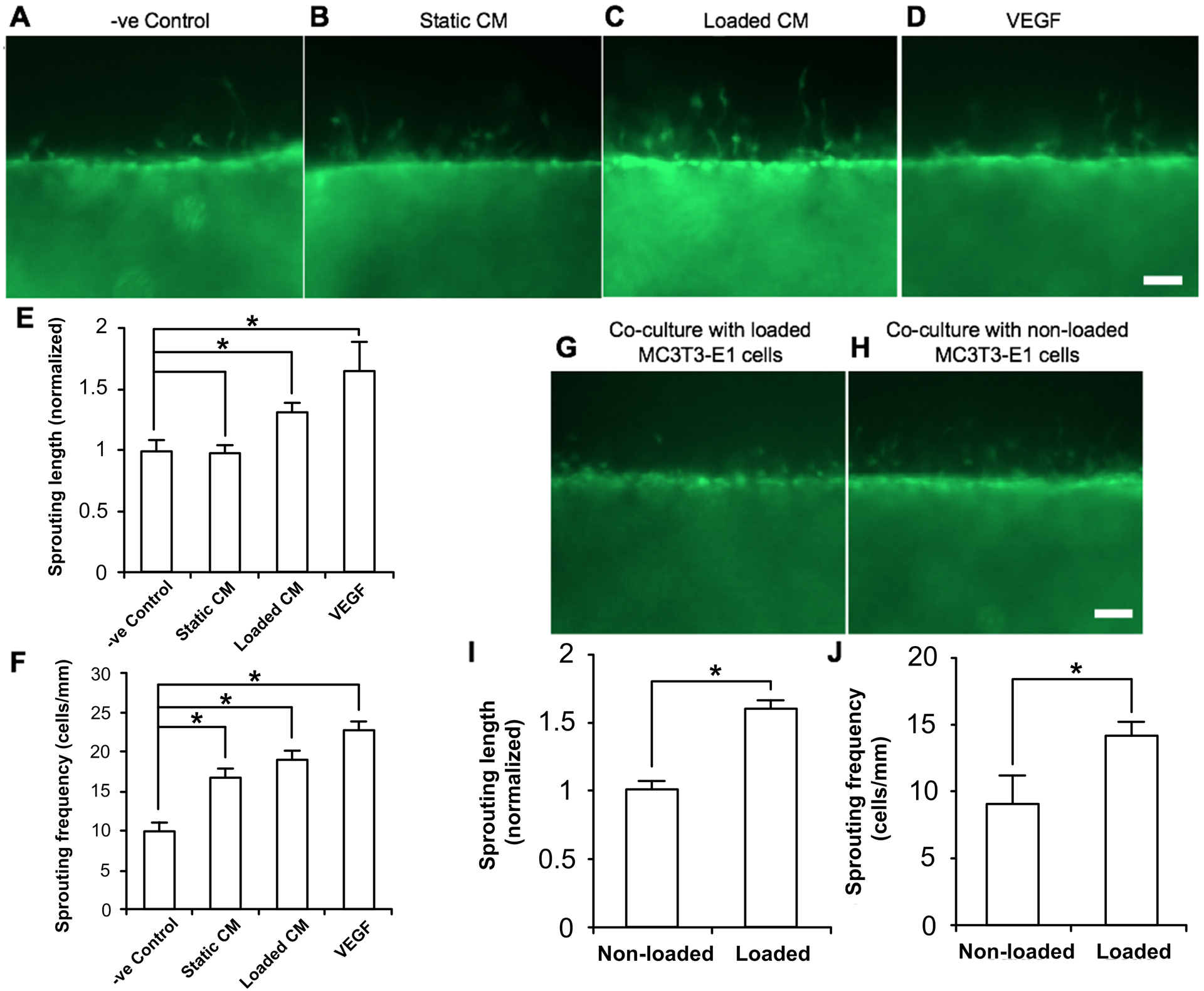

Endothelial cell sprouting enhanced by osteoblast-derived load-induced signals

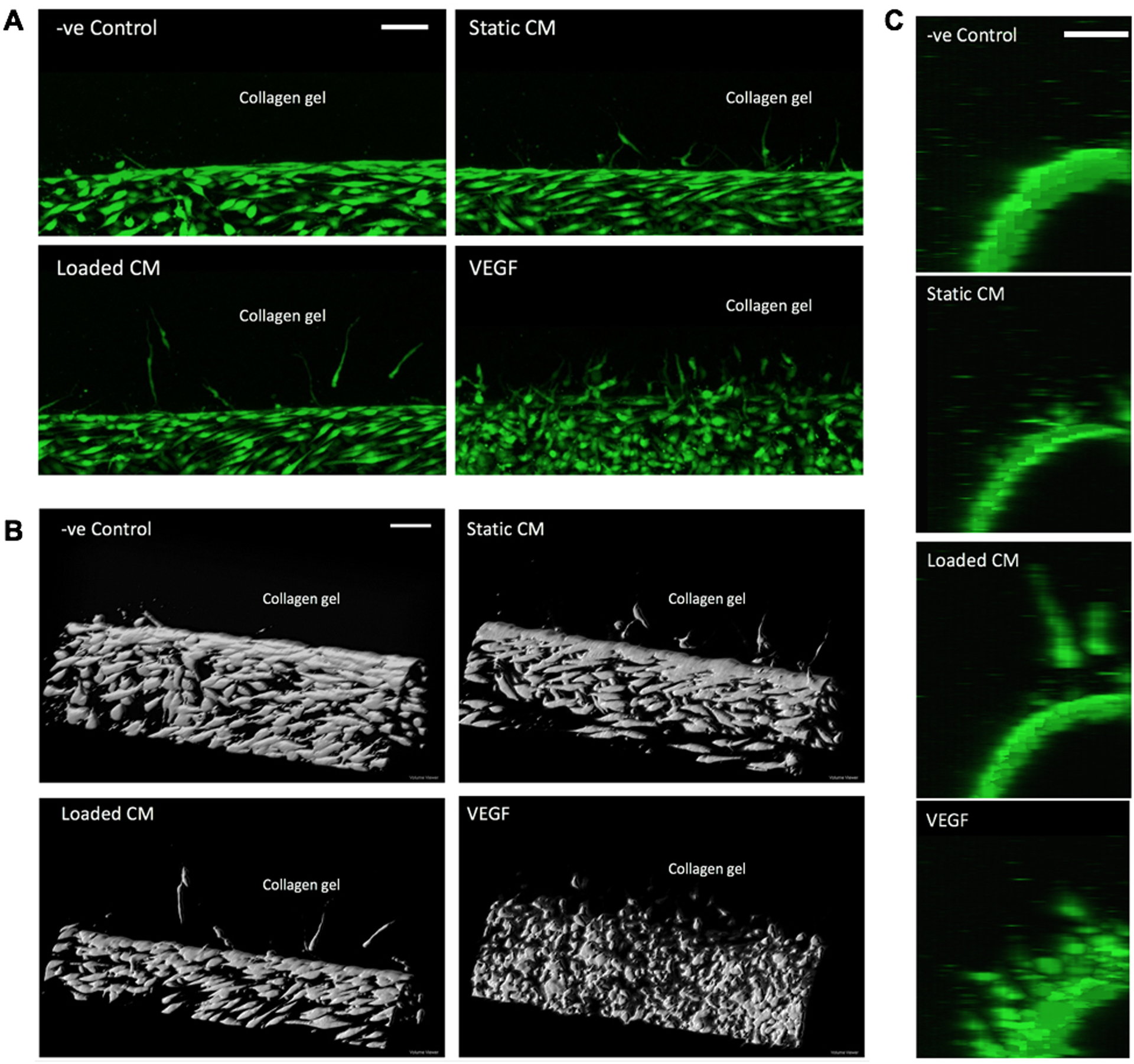

In the eVessel, C166-GFP endothelial cells infiltrated deeper into the collagen gel when cultured with mechanically loaded MC3T3-E1 CM compared with static MC3T3-E1 CM (Fig. 5, Fig. 6A–D). Both types of CM induced a higher number of sprouts compared with fresh MC3T3-E1 media (negative control) (Fig. 6E, F).

Figure 5. Confocal image of the eVessel channel with endothelial cells sprouting in response to soluble factors in adjacent channel.

(A) Project of the confocal image stack. (B) 3D reconstruction of the cell layer inside the channel. The cells penetrated into the collagen gel toward the adjacent channel (above, out of view). VEGF supplementation in adjacent channel induced greatest number of sprouts. CM from loaded osteoblast induced greater depth than static CM and −ve Control. (C) View along the long axis of the channel showing sprouts pointing toward the adjacent channel with conditioned media. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 6. Osteoblast conditioned media-induced sprouting of C166-GFP endothelial cells seeded in the eVessel channel.

(A-D) Sprouting of endothelial cells from the microfluidic channel to the collagen gel in response to osteoblast CM in nearby channel. (E) Quantification of the length of the sprouts, normalized to −ve control group. (F) Quantification of number of sprouts per 1 mm of length along the microfluidic channel. (G-H) Sprouting of endothelial cells in response to mechanically stimulated osteoblasts in nearby channel. (I) Quantification of sprout length, normalized to static group. (J) Quantification of sprouting frequency per 1 mm of channel length. Data bars indicate mean. n > 12. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Endothelial cell sprouting is enhanced by direct osteoblast signaling in response to loading

A constant 0.3 Pa of unidirectional fluid flow shear stress was applied to MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts cultured in one collagen channel. The C166-GFP endothelial cells in the adjacent eVessel showed increased sprouting length and sprouting frequency in response to mechanically stimulated MC3T3-E1 cells compared with MC3T3-E1 cells cultured in static conditions (Fig. 6G–H).

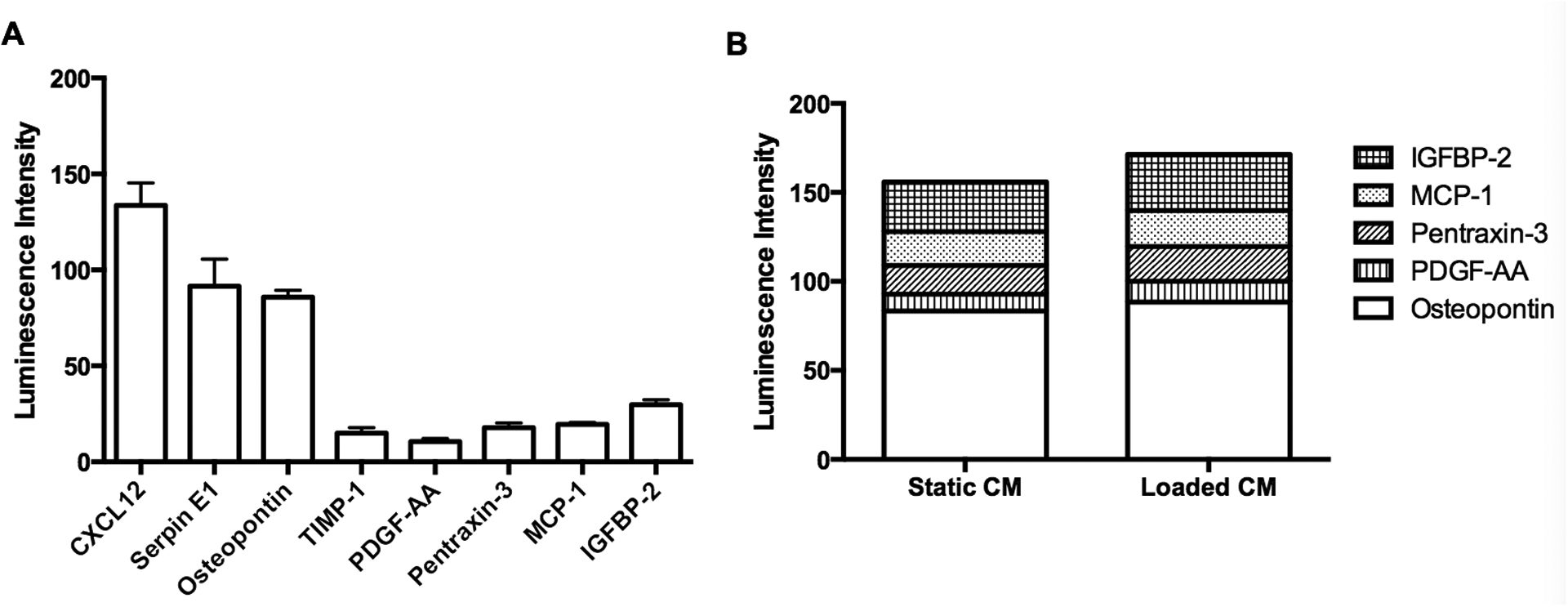

Mechanically-induced release of proangiogenic signals by osteoblasts

Osteoblasts have been shown to release an array of soluble proteins that are known regulators of angiogenesis under normal culture conditions (Fig. 7A). To better understand how mechanical loading affects paracrine signals from osteoblasts to endothelial cells, we used an angiogenic protein array to identify factors released from MC3T3-E1 cells under static and loading conditions. Factors that were highly expressed in MC3T3-E1 cells held under static conditions included CXCL12, serpin E1, and osteopontin. In response to mechanical loading, PDGF-AA concentration was significantly upregulated by 20%, (Fig. 7B) and concentrations of osteopontin, pentraxin-3, MCP-1, and IGFBP-2 exhibited an increasing trend.

Figure 7. Osteoblasts produce angiogenic factors whose expression levels change with mechanical loading.

(A) Soluble proteins that are involved in angiogenesis measured in CM from osteoblasts. (B) Stack column chart of angiogenic factors in CM from osteoblasts cultured in static and loaded conditions.

Discussion

The skeleton is largely a mechanical organ, and mechanical loading is a ubiquitous stimulus to skeletal cells under physiological and pathological conditions. During bone homeostasis and regeneration, the close spatial relationship between endothelial cells and perivascular osteoprogenitors suggests the potential for bidirectional signaling in response to mechanical stimulation. This study demonstrates that osteoblasts release proangiogenic factors that are sufficient to enhance endothelial cell proliferation, migration and sprouting, and that mechanical loading of osteoblasts enhances this endothelial cell response.

Previous studies show that osteogenic cells release proangiogenic factors.13, 16, 49, 65, 66 We confirmed that an array of proangiogenic factors is released from MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts and that mechanical stimulation resulted in elevated concentrations of several of these factors. However, the array of released factors detected in our studies, including osteopontin, PDGF-A, MCP-1, IGFBP-2, differ from previously published work (apart from MCP-1) which reported expression of angiogenin, GRO, IL-6, IL-8, and thrombopoietin in conditioned media from both bone marrow-derived human MSCs and early osteoblasts.16 This discrepancy may be due to differences in both the origin (human versus mouse) and status (primary versus immortalized) of the two cell lines used, and will be explored in future studies.

While many cell types outside of the vascular lineage produce angiogenic factors in vivo, the close spatial approximation between cells of the osteo- and angio-lineages in long bone suggests tight co-regulation in time and space. Indeed, recent evidence shows that a distinct population of endothelial cells support perivascular osteoprogenitors and couples angiogenesis to osteogenesis.13 Perivascular osteoprogenitors are recruited to sites of angiogenesis67, 68,69, where they activate endothelial cells and stabilize the newly forming lumen. A number of signaling molecules have been shown to regulate interactions between osteoprogenitors and endothelial cells, including CXCL12, PDGF, Ang1/2, TGFβ, and Notch. We found that MC3T3-E1 cells released relatively high levels of CXCL12 and PDGF, known cellular recruitment factors, and PDGF release was significantly enhanced in response to mechanical stimulation. Thus, these data support the idea that mechanical information in vivo may be conveyed to newly forming vessels via osteoblast signaling, and while we did not explicitly evaluate endothelial to osteoblast signaling, evidence shows that regulatory signaling between these two cell populations is bidirectional.13

Though CXCL12 was secreted at high levels by MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts, its concentration was not affected by mechanical loading at the time points observed in this study. We previously observed a significant load-induced upregulation of CXCL12 in bone cells in vitro and in vivo18, and a failure to observe a difference in response to flow in the current studies may be due to differences in cell type and the experimental time course.

Approaches that allowed investigation of unidirectional paracrine signaling without direct cell-cell contact between osteoblasts to endothelial cells were employed in these studies. Sprouting was assessed with an eVessel microfluidic device that allowed comparison of the effects of one-sided signaling (endothelial cells in one channel and CM in the adjacent channel) versus bidirectional signaling (endothelial cells in one channel and osteoblasts in the adjacent channel). In both systems, mechanical loading of osteoblasts significantly enhanced sprouting. Microfluidic techniques such, as the eVessel system, hold great promise in exploring the complex crosstalk70 between osteoblasts and endothelial cells under physiologically relevant chemical and physical conditions, and future studies will focus on bidirectional communication.

One of the limitations of our studies was the necessity to restrict the analysis to a 24-hour period after mechanical stimulation. In contrast, the associated physiological processes of load induced remodeling and fracture repair span days or even weeks. A second limitation is that VEGF, one of the most prominent angiogenic factors, was not detected in MC3T3 osteoblast-conditioned media, which may be due to reduced levels of expression observed in osteogenic cells as they become more differentiated.16 It is also possible that the released VEGF was bound to the extracellular matrix instead of released into the media71. Additional cells types must be observed to resolve these discrepancies.

The fluid shear stress was supplied with an orbital shaker system, and the fluid followed a circular path in the well. A bolus of fluid flowed around the center of the well at the same frequency (3 Hz) of applied displacement as the loading platform moved around a vertical axis. With each cycle, the shear stress would be at the maximum under the bolus of fluid, and at the minimum at the opposite side of the well. Therefore, the shear profile on the cells could be considered pulsatile, which is stimulatory to MC3T3-E1 cells.59 A range of shear stress was produced by this system with estimated maximum of 2 Pa, and average shear stress of 0.8 Pa. This range is within the stimulatory range for osteogenic cells.72, 73 In healthy bone, 9.8 m s−2 of loading is estimated to produce 0.5 Pa of shear stress in > 75% of the marrow tissue, with maximum of 5 Pa at the marrow-bone interface.56 Strain at the fracture site is estimated to be larger compared to intact bone32, which may lead to higher fluid shear stress on the cells.

Conclusion

Mechanical force at the cellular level is increasingly recognized as a potent stimulus during homeostasis and healing. This is especially important for cells in structural organs such as bone. Tissue level micro-motion is known to promote fracture healing33, but the cellular level mechanism is still unclear. The bone microenvironment supports complex crosstalk between osteogenic and endothelial cells. This study reveals that mechanical signals enhance the release of “osteokines” that are known to regulate different phases of angiogenesis. We showed that conditioned media from mechanically-loaded osteoblasts induced endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and sprouting. In addition, our protein array showed enhanced release of multiple angiogenic factors by fluid shear stress. These include factors that participate in both direct and indirect signaling to endothelial cells.

Acknowledgements

We thank Claire Shortt for assistance with imaging.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the NYU Center for Skeletal and Craniofacial Biology Pilot Award (ABC), NYU Center for Translational Science Awards 1UL1TR001445, 1KL2 TR001446, and 1TL1 TR001447 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) (ABC), and New York University Research Challenge Fund (WC).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

References

- 1.Lewis O, Bone & Joint Journal, 1956, 38, 928–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson B and Towler DA, Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 2012, 8, 529–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Risau W, Nature, 1997, 386, 671–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stegen S, van Gastel N and Carmeliet G, Bone, 2015, 70, 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuasa M, Mignemi NA, Barnett JV, Cates JM, Nyman JS, Okawa A, Yoshii T, Schwartz HS, Stutz CM and Schoenecker JG, Bone, 2014, 67, 208–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang TD, Salim A, Xia W, Nacamuli RP, Guccione S, Song HM, Carano RA, Filvaroff EH, Bednarski MD and Giaccia AJ, Journal of bone and mineral research, 2005, 20, 1114–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sfeir C, Ho L, Doll BA, Azari K and Hollinger JO, in Bone Regeneration and Repair: Biology and Clinical Applications, eds. Lieberman JRand Friedlaender GE, Humana Press, 2005, pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerhardt H, Golding M, Fruttiger M, Ruhrberg C, Lundkvist A, Abramsson A, Jeltsch M, Mitchell C, Alitalo K and Shima D, The Journal of cell biology, 2003, 161, 1163–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Hinsbergh VW and Koolwijk P, Cardiovascular research, 2008, 78, 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain RK, Nature medicine, 2003, 9, 685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Augustin HG, Koh GY, Thurston G and Alitalo K, Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 2009, 10, 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang F-J, You W-K, Bonaldo P, Seyfried TN, Pasquale EB and Stallcup WB, Developmental biology, 2010, 344, 1035–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kusumbe AP, Ramasamy SKand Adams RH, Nature, 2014, 507, 323–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramasamy SK, Kusumbe AP and Adams RH, Trends in cell biology, 2015, 25, 148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maes C, Kobayashi T, Selig MK, Torrekens S, Roth SI, Mackem S, Carmeliet G and Kronenberg HM, Developmental cell, 2010, 19, 329–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoch AI, Binder BY, Genetos DC and Leach JK, PLoS One, 2012, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawakami Y, Ii M, Matsumoto T, Kuroda R, Kuroda T, Kwon SM, Kawamoto A, Akimaru H, Mifune Y and Shoji T, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 2015, 30, 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leucht P, Temiyasathit S, Russell A, Arguello JF, Jacobs CR, Helms JA and Castillo AB, Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 2013, 31, 1828–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceradini DJ, Kulkarni AR, Callaghan MJ, Tepper OM, Bastidas N, Kleinman ME, Capla JM, Galiano RD, Levine JP and Gurtner GC, Nature medicine, 2004, 10, 858–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myers TJ, Longobardi L, Willcockson H, Temple JD, Tagliafierro L, Ye P, Li T, Esposito A, Moats‐Staats BM and Spagnoli A, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Senger DR, Ledbetter SR, Claffey KP, Papadopoulos-Sergiou A, Peruzzi C and Detmar M, The American journal of pathology, 1996, 149, 293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colla S, Morandi F, Lazzaretti M, Rizzato R, Lunghi P, Bonomini S, Mancini C, Pedrazzoni M, Crugnola M and Rizzoli V, Leukemia, 2005, 19, 2166–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caplan AI and Correa D, Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 2011, 29, 1795–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrew J, Hoyland J, Freemont A and Marsh D, Bone, 1995, 16, 455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horner A, Bord S, Kemp P, Grainger D and Compston JE, Bone, 1996, 19, 353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niu J, Azfer A, Zhelyabovska O, Fatma S and Kolattukudy PE, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2008, 283, 14542–14551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong KH, Ryu J and Han KH, Blood, 2005, 105, 1405–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niu J, Wang K, Zhelyabovska O, Saad Y and Kolattukudy PE, Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 2013, 347, 288–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez-Grande B, Varghese L, Molina-Holgado F, Rajkovic O, Garlanda C, Denes A and Pinteaux E, Journal of Neuroinflammation, 2015, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Das SK, Bhutia SK, Azab B, Kegelman TP, Peachy L, Santhekadur PK, Dasgupta S, Dash R, Dent P and Grant S, Cancer research, 2013, 73, 844–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castillo AB and Leucht P, Current rheumatology reports, 2015, 17, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lacroix D and Prendergast P, Journal of biomechanics, 2002, 35, 1163–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolf S, Janousek A, Pfeil J, Veith W, Haas F, Duda G and Claes L, Clinical Biomechanics, 1998, 13, 359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardner MJ, van der Meulen MC, Demetrakopoulos D, Wright TM, Myers ER and Bostrom MP, Journal of orthopaedic research, 2006, 24, 1679–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boerckel JD, Uhrig BA, Willett NJ, Huebsch N and Guldberg RE, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2011, 108, E674–E680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen J-H, Liu C, You L and Simmons CA, Journal of Biomechanics, 2010, 43, 108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kapur S, Baylink DJ and Lau KHW, Bone, 2003, 32, 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McAllister TN and Frangos JA, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 1999, 14, 930–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy B, Das T, Mishra D, Maiti TK and Chakraborty S, Integrative Biology (United Kingdom), 2014, 6, 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamamura K, Swarnkar G, Tanjung N, Cho E, Li J, Na S and Yokota H, Connective Tissue Research, 2012, 53, 398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castillo AB, Blundo JT, Chen JC, Lee KL, Yereddi NR, Jang E, Kumar S, Tang WJ, Zarrin S, Kim JB and Jacobs CR, PLoS ONE, 2012, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Castillo AB, Triplett JW, Pavalko FM and Turner CH, American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2014, 306, E937–E944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakker A, Klein-Nulend J and Burger E, Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 2004, 320, 1163–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang B, Lai X, Price C, Thompson WR, Li W, Quabili TR, Tseng WJ, Liu XS, Zhang H, Pan J, Kirn-Safran CB, Farach-Carson MC and Wang L, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 2014, 29, 878–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng BX, Zhao SJ, Luo J, Sprague E, Bonewald LF and Jiang JX, Journal of bone and mineral research, 2001, 16, 249–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu C, Zhao Y, Cheung W-Y, Gandhi R, Wang L and You L, Bone, 2010, 46, 1449–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J-N, Zhao Y, Liu C, Han ES, Yu X, Lidington D, Bolz S-S and You L, Bone, 2015, 79, 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu C, Zhang X, Wu M and You L, Journal of biomechanics, 2015, 48, 4221–4228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deckers MM, van Bezooijen RL, van der Horst G, Hoogendam J, van der Bent C, Papapoulos SE and C. W. Löwik, Endocrinology, 2002, 143, 1545–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prasadam I, Zhou Y, Du Z, Chen J, Crawford R and Xiao Y, Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 2014, 386, 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thi MM, Suadicani SO and Spray DC, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2010, 285, 30931–30941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheung WY, Liu C, Tonelli‐Zasarsky RM, Simmons CA and You L, Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 2011, 29, 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang S-J, Greer P and Auerbach R, In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Animal, 1996, 32, 292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Birmingham E, Grogan J, Niebur G, McNamara L and McHugh P, Annals of biomedical engineering, 2013, 41, 814–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Metzger TA, Kreipke TC, Vaughan TJ, McNamara LM and Niebur GL, Journal of biomechanical engineering, 2015, 137, 011006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coughlin TR and Niebur GL, Journal of Biomechanics, 2012, 45, 2222–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cowin SC, Gailani G and Benalla M, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 2009, 367, 3401–3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomas JMD, Chakraborty A, Sharp MK and Berson RE, Biotechnology progress, 2011, 27, 460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGarry JG, Klein-Nulend J and Prendergast PJ, Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 2005, 330, 341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ley K, Lundgren E, Berger E and Arfors K, Blood, 1989, 73, 1324–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arnaoutova I, George J, Kleinman HK and Benton G, Angiogenesis, 2009, 12, 267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nguyen D-HT, Stapleton SC, Yang MT, Cha SS, Choi CK, Galie PA and Chen CS, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2013, 110, 6712–6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chrobak KM, Potter DR and Tien J, Microvascular research, 2006, 71, 185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kou S, Pan L, van Noort D, Meng G, Wu X, Sun H, Xu J and Lee I, Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 2011, 408, 350–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grellier M, Bordenave L and Amedee J, Trends in biotechnology, 2009, 27, 562–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ramasamy SK, Kusumbe AP, Wang L and Adams RH, Nature, 2014, 507, 376–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Collett G, Wood A, Alexander MY, Varnum BC, Boot-Handford RP, Ohanian V, Ohanian J, Fridell Y-W and Canfield AE, Circulation research, 2003, 92, 1123–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Doherty MJ, Ashton BA, Walsh S, Beresford JN, Grant ME and Canfield AE, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 1998, 13, 828–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Armulik A, Genové G and Betsholtz C, Developmental cell, 2011, 21, 193–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu C, Middleton K and You L, in Integrative Mechanobiology: Micro-and Nano-Techniques in Cell Mechanobiology, eds. Sun Y, Kim D-H and Simmons CA, Cambridge University Press, 2015, vol. 14, p. 245. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park JE, Keller G-A and Ferrara N, Molecular biology of the cell, 1993, 4, 1317–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li J, Rose E, Frances D, Sun Y and You L, Journal of Biomechanics, 2012, 45, 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kamioka H, Sugawara Y, Murshid SA, Ishihara Y, Honjo T and Takano-Yamamoto T, Journal of bone and mineral research, 2006, 21, 1012–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]