Abstract

Background

The clinical use of serum creatine (sCr) and cystatin C (CysC) in kidney function evaluation of critically ill patients has been in continuous discussion. The difference between estimated glomerular filtration rate calculated by sCr (eGFRcr) and CysC (eGFRcysc) of critically ill COVID-19 patients were investigated in this study.

Methods

This is a retrospective, single-center study of critically ill patients with COVID-19 admitted in intensive care unit (ICU) at Wuhan, China. Control cases were moderate COVID-19 patients matched in age and sex at a ratio of 1:1. The eGFRcr and eGFRcysc were compared. The association between eGFR and death were analyzed in critically ill cases. The potential factors influencing the divergence between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc were explored.

Results

A total of 76 critically ill COVID-19 patients were concluded. The mean age was 64.5 ± 9.3 years. The eGFRcr (85.45 (IQR 60.58–99.23) ml/min/1.73m2) were much higher than eGFRcysc (60.6 (IQR 34.75–79.06) ml/min/1.73m2) at ICU admission. About 50 % of them showed eGFRcysc < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 while 25% showed eGFRcr < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (χ2 = 10.133, p = 0.001). This divergence was not observed in moderate group. The potential factors influencing the divergence included serum interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) level as well as APACHEII, SOFA scores. Reduced eGFRcr (<60 mL/min/1.73 m2) was associated with death (HR = 1.939, 95%CI 1.078–3.489, p = 0.027).

Conclusions

The eGFRcr was generally higher than eGFRcysc in critically ill COVID-19 cases with severe inflammatory state. The divergence might be affected by inflammatory condition and illness severity. Reduced eGFRcr predicted in-hospital death. In these patients, we advocate for caution when using eGFRcysc.

Keywords: COVID-19, critically ill, eGFR, CysC, SCr

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has become a worldwide pandemic. Over 176 million cases and 3.8 million deaths were reported all over the world [1]. Besides alveolar damage, the involvements of other organs including kidney [2] have also been widely observed, especially in critically ill patients. The incidence of COVID-19 associated acute kidney injury (AKI) was reported as high as 36.6–46% in large cohorts of hospitalized patients [3–5], and this proportion was even higher in patients admitted to ICUs [6,7]. What’s more, the prevalence of kidney disease on admission and the kidney involvement during hospitalization in COVID-19 patients were associated with in-hospital mortality [8,9]. Therefore, correct estimation of kidney damage plays a very important role in improving prognosis by prompt intervention, appropriate dosing of drugs and adjustment of therapeutic strategies. In clinical practice, serum creatine (sCr) and cystatine C (CysC) were common biomarkers used to evaluate the glomerular filtration function. However, their performance in critically ill patients was not universally agreed [10–15]. Some studies [10,16–18] considered sCr highly misleading in ICU patients because of muscle mass loss and volume overload in many critically ill patients. CysC is also influenced by several factors such as age [19,20], corticosteroids administrations [21–23], inflammation [19,24], and diabetes status [25,26]. So far, little is known about the performance of sCr and CysC for glomerular filtration rate (GFR) estimation in critically ill patients with COVID-19. We conducted a retrospective observational study in critically ill patients with COVID-19 to explore the difference of sCr and CysC in GFR estimation and their relevance with prognosis.

Method

Study design and participants

This is a single-center, retrospective study conducted in ICU designated for critically ill patients with COVID-19 at the Sino-French New City Campus of Tongji Hospital in Wuhan, China. All of the patients in the ICU who met the criteria of a critically ill case of COVID-19 and had sCr as well as CysC tested at the same time between January 29 and March 20, 2020 were included. Moderate COVID-19 patients matched in age and sex at a ratio of 1:1 from non-ICU wards on the corresponding period were selected as control cases. The diagnosis and classification standards are as follows.

All confirmed patients were diagnosed according to the Guideline of Chinese National Health Commission (Fifth Trial Edition) [27]. The clinical diagnosis criteria were as follows: (1) fever or respiratory symptoms, (2) leukopenia or lymphopenia, (3) computerized tomography scan showing radiographic abnormalities in lung. Patients with two or more clinical diagnosis criteria and a positive result to high-throughput sequencing or RT-PCR assay of SARS-CoV-2 were defined as confirmed case with COVID-19. Severity of the disease was staged into mild, moderate, severe, and critical types. Critically ill COVID-19 cases were defined as including at least one of the following: septic shock, respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, and a combination of other organ failures and admission to ICU. A severe case was defined as (1) respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min; (2) oxygen saturation ≤93%, or (3) PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤ 300 mm Hg. A moderate case was defined as clinical symptoms of fever and cough, with radiographic evidence of pneumonia but did not meet the criteria of severe cases. A mild case was defined as mild clinical symptoms without radiographic evidence of pneumonia by chest CT scan.

This study was approved by the PUMCH Institutional Review Board (ZS-2328, SK-1197).

Data collection and definitions

Presence of comorbidities, laboratory data, treatment regimens, and clinical outcomes was collected from the electronic medical records, laboratory results, and medical order lists. The sCr was measured by enzyme colorimetry while CysC was measured by particle-enhanced immunonephelometric assay with nephelometer. The eGFR was calculated at ICU admission. Fever was defined as axillary temperature of at least 37.3 °C. Sepsis and septic shock were defined according to the 2016 Third International Consensus Definition for Sepsis and Septic Shock [28]. Hypoalbuminemia was defined as serum albumin < 30 g/L. Leukocytosis was defined as white blood cell (WBC) count >9.5 × 109/L. Lymphocytopenia was defined as lymphocyte <1.1 × 109/L. D-dimer levels were classified into four categories: <0.5 as category 1, 0.5–5.0 as category 2, 5.0–21.0 as category 3, and >21.0 as category 4. Elevated sCr was defined as >104 μmol/L in men and >84 μmol/L in women. Declined sCr was defined as <59 μmol/L in men and <45 μmol/L in women. Elevated CysC was defined as >1.55 mg/L. Declined CysC was defined as <0.6 mg/L. Reduced eGFR was defined as eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The primary outcome was death in hospital before March 20th. Disease course was defined as time from illness onset to death or transference out from ICU.

Evaluation of glomerular filtration rate

The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated according to CKD-EPI equations as follows(Table 1).

The divergence between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc

To explore the factors influencing the divergence between eGFR-cr and eGFRcysc in critically ill group, patients were sub-grouped by the divergence degree between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc. The divergence degree between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc was measured by the difference ratio (△eGFRcr-cysc %)defined as △eGFRcr-cysc divided by mean of eGFRcr and eGFRcysc. That is, △eGFRcr-cysc %= Group 1, group 2 and group 3 represented patients with △eGFRcr-cysc % 0–25 %, 25 %–45 %, and >45 %, respectively [1]. Clinical features among sub-groups were analyzed. The association between eGFR and death were explored.

Statistical analysis

Categoric variables were expressed as frequency and percentage and continuous variables were expressed by mean ± SD (for data that were normally distributed), or median and inter-quartile range (IQR) (for data that were not normally distributed). When the data were normally distributed, independent t tests were used to compare the means of continuous variables. Otherwise, the Mann–Whitney test was used. The χ2 test was used to compare the differences of categoric variables. Cox proportional hazards models were used to analyze the risk factors related to death. Kruskal–Wallis H test and ordinal multi-categorical logistic regression was used to identify the potential factors influencing the divergence. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 software. A p-value of 0.05 is statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of critically ill cases and moderate cases with COVID-19

A total of 76 critically ill patients and 76 moderate cases matched with age and sex were included. The mean age of the critically ill patients was 64.5 ± 9.3 years and the male: female ratio was 49:27 (Table 2). In critically ill patients, the median Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHEII) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores were 13 (IQR, 10–18.75) and 5 (IQR, 4–8), respectively at admission to ICU. Vasopressors were needed in 63.2 %(48/76) of patients, and 78.9% (60/76) of patients received invasive mechanic ventilation. Compared with moderate cases, significant elevation of inflammatory markers such as high-sensitivity C -reactive protein, IL-6, and ferritin were also observed in these patients (Table 2).

Table 1.

Description of the formulas used.

| Female | Male | |

|---|---|---|

| CKD-EPI creatinine equation | sCr ≤ 62: 144*(sCr/62)−0.329* 0.993Age sCr > 62: 144*(sCr/62)−1.209 * 0.993Age |

sCr ≤ 80: 141*(sCr/80)−0.411* 0.993Age sCr > 80: 141*(sCr/80)−1.209 * 0.993Age |

| CKD-EPI cystatin C equation | CysC ≤ 0.8: 133*(CysC/0.8)−0.499*0.996Age * 0.932 CysC > 0.8: 133*(CysC/0.8)−1.328*0.996Age * 0.932 |

CysC ≤ 0.8: 133*(CysC/0.8)−0.499*0.996Age CysC > 0.8: 133*(CysC/0.8)−1.328*0.996Age |

The units of sCr and CysC were umol/L and mg/L, respectively.

Table 2.

Demographic, clinical characteristics, and laboratory findings of critically ill and moderate patients.

| Critically ill | Moderate | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age (years) | 64.5 ± 9.3 | 62.9 ± 9.3 | 0.182 |

| Male | 49 (64.5 %) | 49 (64.5 %) | 1 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Death, n (%) | 56 (73.7 %) | 0 | – |

| Disease course (days) | 29 (21–38) | 41 (32–50) | <0.001 |

| Time of hospitalization (days) | 17 (9–27) | 16 (8.25–22) | 0.269 |

| Time of ICU (days) | 9 (5.25–18) | – | – |

| Time from illness to ICU (days) | 16.5 (11–25) | – | – |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 35 (46.1 %) | 30 (39.5 %) | 0.412 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (23.7 %) | 15 (19.7 %) | 0.555 |

| Coronary heart disease | 16 (21.1 %) | 8 (10.5 %) | 0.075 |

| Current smoker | 11 (15.1 %) | 7 (9.3 %) | 0.286 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 5 (6.6 %) | 2 (2.6 %) | 0.246 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| White blood cell count (×109/L) (3.50–9.50) | 11.57 (8.04–16.46) | 5.35 (4.27–6.46) | <0.001 |

| Leukocytosis | 52 (68.4 %) | 3 (4.0 %) | |

| Neutrophil count (×109/L) (1.80–6.30) | 10.24 (7.37–15.12) | 3.25 (2.54–4.16) | <0.001 |

| Lymphocytes (×109/L) (1.10–3.20) | 0.56(0.40–0.78) | 1.15 (0.95–1.76) | <0.001 |

| Lymphocytopenia | 71 (93.4 %) | 32 (42.7 %) | |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) (115–150) | 108 (123.5–138) | 125 (112–137) | 0.607 |

| Anemia | 36 (47.4 %) | 30 (39.5 %) | 0.361 |

| Platelets (×109/L) (125–350) | 165 (101.25–220.25) | 220 (184–259) | <0.001 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 25 (32.9 %) | 32 (42.7 %) | |

| Serum albumin (g/L) (35–52) | 28.5 (26.28–32.05) | 38.3 (35.6–41.7) | <0.001 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 48 (63.2 %) | 3 (3.9 %) | <0.001 |

| sCr (μmol/L) (45–84) | 76.5 (53.25–104.25) | 72.5 (61.25–82.25) | 0.359 |

| Elevated sCr, n (%) | 19 (25 %) | 5 (6.6 %) | 0.002 |

| Declined sCr, n (%) | 13 (17.1 %) | 3 (3.9 %) | 0.008 |

| eGFR-Cr (ml/min/1.73m2) | 85.45 (60.58–99.23) | 92.04 (80.45–97.81) | 0.119 |

| Reduced eGFR-Cr | 19 (25 %) | 5 (6.6 %) | 0.002 |

| CysC (mg/L) (0.60–1.55) | 1.17 (0.99–1.78) | 0.99 (0.88–1.09) | <0.001 |

| Elevated CysC, n (%) | 24 (31.6 %) | 4 (5.3 %) | <0.001 |

| Declined CysC, n (%) | 0 | 0 | |

| eGFR-CysC (ml/min/1.73m2) | 60.60 (34.75–79.06) | 74.55 (65.58–91.19) | <0.001 |

| Reduced eGFR-CysC | 38 (50 %) | 11 (14.5 %) | <0.001 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) (<7) | 54.88 (29.76–169.35) | 6.81 (3.12–16.31) | <0.001 |

| Ferritin (mg/ml) (15–150) | 1302.9 (730.45–2327.88) | 357.4 (258.0–580.8) | <0.001 |

| D-dimer (μg/ml FEU) (<0.5) | |||

| <0.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.5–5.0 | 0 | 28 (37.3 %) | |

| 5.0–21.0 | 40 (54.8 %) | 15 (20 %) | <0.001 |

| >21.0 | 33 (45.2 %) | 32 (42.7 %) | |

| hsCRP (mg/L) (<1) | 103.05 (59.58–153.8) | 3.50 (0.93–12.65) | <0.001 |

Renal functions in critically ill patients and moderate patients

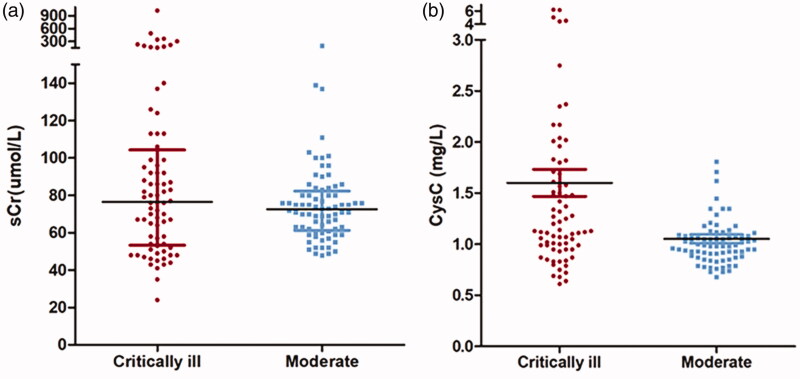

The median sCr and eGFRcr of critically ill patients were 76.5 (IQR 53.25–104.25)μmol/L and 85.45 (IQR 60.58–99.23) ml/min/1.73m2, which was comparable with moderate group (Table 2). The sCr of critically ill patients had a larger extent of dispersion with a coefficient of variation of 1.189 while the distribution was relatively concentrated in moderate cases with a coefficient of variation of 0.304 (Figure 1; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Comparison of sCr and CysC between critically ill patients and moderate patients. (a) The SCr of critically ill patients has an equivalent median with moderate patients but distributed more dispersedly; (b) The median of CysC was significantly higher in critically ill patients than in moderate patients.

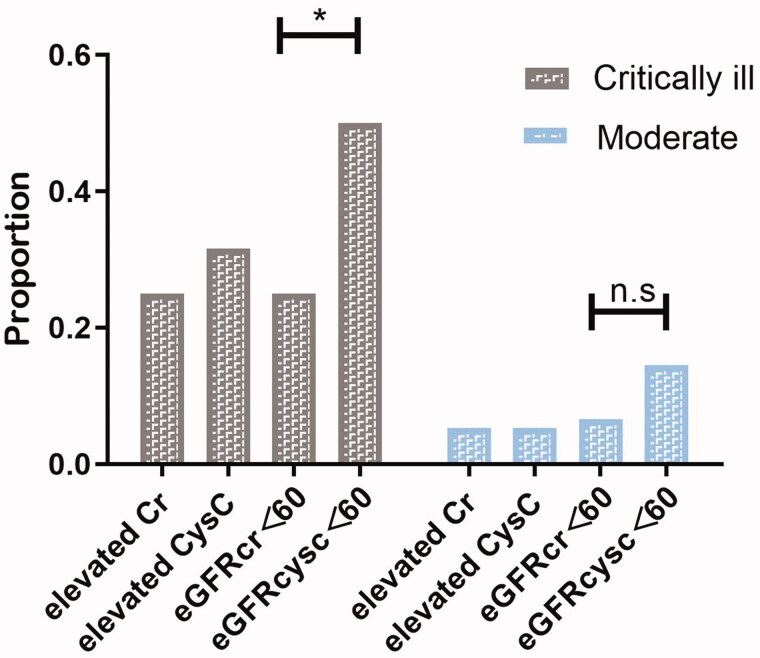

The level of median sCysC of critically ill patients was much higher than that in the moderate group (1.17 (IQR, 0.99–1.78)mg/L vs. 0.99(IQR, 0.88–1.09) mg/L, p<0.001) and the eGFRcysc was significantly lower (60.6 (IQR, 34.75–79.06) ml/min/1.73 m2 vs 74.55 (IQR,65.58-91.19) ml/min/1.73 m2, p<0.001) (Table 2). In critically ill patients, eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 were present in 50 % of the patients when calculated with CysC and this proportion was only 25 % when calculated with sCr (χ2 = 10.133, p = 0.001). This difference was not significant in control group (14.5 % vs 6.6 %, χ2 = 2.515, p = 0.113) (Tables 2 and 4; Figure 2).

Table 3.

Demographic, clinical characteristics, and laboratory findings of nonsurvivors and survivors in critically ill patients.

| Non-survivors n = 56 |

Survivors n = 20 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age (year) | 65.4 ± 7.7 | 62.0 ± 12.7 | 0.274 |

| Male, n (%) | 38 (67.9 %) | 11 (55 %) | 0.302 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| APACHEII | 14 (10–20) | 11 (9.25–13.0) | 0.021 |

| SOFA | 6 (4–8.75) | 4 (3–5) | 0.002 |

| Invasive ventilation | 50 (89.3 %) | 10 (50 %) | 0.002 |

| Glucocorticoids | 48 (85.7 %) | 15 (75 %) | 0.739 |

| Vasopressors | 44 (78.6 %) | 4 (20 %) | <0.001 |

| Death, n (%) | 56 (100 %) | 0 | |

| Disease course | 26 (20–35) | 35.5 (27–49) | 0.016 |

| Time of hospitalization (days) | 13.5 (9–23) | 16 (8.25–22) | 0.007 |

| Time of ICU (days) | 8.5 (5–13) | 14 (7–27) | 0.015 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Hypertension | 19 (33.9 %) | 16 (80 %) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (19.6 %) | 7 (35 %) | 0.280 |

| Coronary heart disease | 11 (19.6 %) | 5 (25 %) | 0.853 |

| Current smoker | 8 (14.3 %) | 3 (15 %) | 0.992 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 (1.8 %) | 4 (20 %) | 0.016 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| White blood cell count (×109/L) | 12.11 (9.23–18.86) | 9.32 (6.25–12.7) | 0.017 |

| Neutrophil count (×109/L) | 10.94 (8.11–17.27) | 8.38 (5.05–11.08) | 0.017 |

| Lymphocytes (×109/L) | 0.53 (0.38–0.73) | 0.65 (0.41–0.83) | 0.243 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 126 (109–140) | 114 (93.75–133.25) | 0.115 |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 157 (77–217) | 181 (134.5–270.8) | 0.075 |

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 27.75 (25.08–31.23) | 30.40 (28.1–33.1) | 0.035 |

| Serum calcium (mmol/L) (2.15–2.50) | 2.21 (.95–2.31) | 2.07 (1.91–2.20) | 0.115 |

| Serum inorganic phosphorus (mmol/L) (0.81–1.45) | 0.99 (0.78–1.15) | 0.98 (0.86–1.37) | 0.591 |

| Serum uric acid (mmol/L) (142.8–339.2) | 214.0 (134.0–302.8) | 214.0 (161.3–334.8) | 0.483 |

| Urea (mmol/L) (2.6–7.5) | 8.25 (5.43–11.0) | 8.80 (6.05–15.15) | 0.286 |

| sCr (umol/L) | 78.5 (54.75–111.25) | 74.0 (45.75–90.75) | 0.190 |

| Elevated sCr, n (%) | 15 (26.8 %) | 4 (20 %) | 0.547 |

| Declined sCr, n (%) | 6 (10.7 %) | 7 (35 %) | 0.033 |

| eGFR-Cr (ml/min/1.73m2) | 85.85 (55.78–98.0) | 84.85(70.85–107.85) | 0.392 |

| eGFR-Cr<60 | 16 (28.6 %) | 5 (15 %) | 0.229 |

| CysC (mg/L) | 1.21 (0.95–1.83) | 1.13 (1.05–1.50) | 0.972 |

| Elevated CysC, n (%) | 20 (35.7 %) | 4 (20 %) | 0.194 |

| Declined CysC, n (%) | 0 | 0 | |

| eGFR-CysC (ml/min/1.73m2) | 57.51 (30.51–81.54) | 60.86 (43.55–67.96) | 0.972 |

| eGFRcr-cysc (ml/min/1.73m2) | 68.69 (41.72–91.23) | 74.70 (57.66–89.63) | 0.663 |

| eGFRcr-cysc<60 | 24 (42.9 %) | 5 (25 %) | 0.158 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 116.5 (37.15–220.4) | 29.76 (19.16–38.38) | <0.001 |

| IL-8 (pg/ml) (<62) | 29.65 (15.30–63.85) | 22.9 (9.55–31.25) | 0.045 |

| IL-10 (pg/ml) (<9.1) | 13.5 (7.9–20.3) | 7.8 (6.05–12.45) | 0.057 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) (<8.1) | 10.55 (7.18–19.35) | 9.8 (6.95–13.8) | 0.459 |

| Ferritin (mg/ml) | 1427.1 (829.15–2483.15) | 867.7 (649.7–1852.5) | 0.057 |

| D-dimer (mg/ml FEU), n (%) | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.5–5.0 | 16 (28.6 %) | 12 (60 %) | |

| 5.0–21.0 | 12 (21.4 %) | 3 (15 %) | 0.048 |

| >21.0 | 27 (48.2 %) | 5 (25 %) | |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 110.20 (64.53–162.55) | 60.25 (31.43–117.35) | 0.009 |

APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Table 4.

Renal function estimation using sCr and CysC showed differences in the same 76 critical ill patients.

| SCr | CysC | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR | 85.45 (60.58–99.23) | 60.6 (34.75–79.06) | <0.001 |

| Reduced eGFR | 19 (25 %) | 38 (50 %) | 0.001 |

| Elevated | 19 (25 %) | 24 (31.6 %) | 0.368 |

| Declined | 13 (17.1 %) | 0 | <0.001 |

Reduced eGFR defined as eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Elevated sCr was defined as >104 μmol/L in men and >84 μmol/L in women. Declined sCr was defined as <59 μmol/L in men and <45 μmol/L in women. Elevated CysC was defined as >1.55 mg/L. Declined CysC was defined as <0.6 mg/L.

Figure 2.

Proportion of different definition of “renal dysfunction” including elevated sCr, elevated CysC, eGFRcr<60, eGFRcysc<60 in critically ill patients and moderate patients. In critically ill group, eGFRcysc less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 presented in 50 % patients and eGFRcr less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 presented in 25 % (p = 0.001). This divergence was not obvious in the moderate group (14.5 % vs 6.6 %, χ2 = 2.515, p = 0.113). The proportion of elevated sCr and elevated CysC was 25 % and 31.6 % (p = 0.368)in critically ill patients. In moderate group, the proportion of elevated sCr was equal to elevated CysC (20 %).

Factors influencing the divergence between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc

In the critically ill patients with COVID-19, higher eGFRcr than eGFRcysc was present in 86.8 % (66/76). No significant difference in age, gender, plasma albumin level, plasma calcium level etc was found among three subgroups graded by the divergence degree between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc(△eGFRcr-eGFRcysc %). Compared with group 1, patients in group 3 had significantly higher inflammation factor levels including IL-6 97.72 (IQR, 38.44–290.65) pg/ml vs. 30.21 (IQR, 12.46–44.92) pg/ml, p = 0.005) and TNF-α13.1 (IQR, 8.6–20.4) pg/ml vs. 7.6 (IQR, 6.3–11.6) pg/ml, p = 0.022) (Table 5, Figure 4). Meanwhile, the APACHEII scores were higher in groups 2 and 3 than in group 1 (17(IQR, 10.5–20) vs. 14(IQR, 12–20) vs. 10(IQR, 8–13), p = 0.001) (Table 5, Figure 4). Ordinal multi-categorical logistic regression indicated a positive correlation between the △eGFRcr-eGFRcysc % and TNF-α level (OR = 9.49, 95%CI 1.45–62.05, χ2 = 5.52, p = 0.019) (grouped by quartile).

Table 5.

Differences of IL-6, TNF-α and APACHEII among three subgroups graded by the gap between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc.

| Median (IQR) | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | p Value (overall) | p Value (1 vs 2)* | p Value (1 vs 3) | p Value (2 vs 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL6 (pg/ml)b | 30.21 (12.46–44.92) | 56.36 (28.43–203.98) | 97.72 (38.44–290.65) | 0.006 | 0.097 | 0.005 | 1.000 |

| TNFα (pg/ml)c | 7.6 (6.3–11.6) | 11.5 (7.3–16.7) | 13.1 (8.6–20.4) | 0.027 | 0.27 | 0.022 | 0.936 |

| APACHEII | 10 (8–13) | 14 (12–20) | 17 (10.5–20) | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 1.000 |

| SOFA | 4 (1–5) | 6 (4–8) | 6.5 (4–8.75) | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 1.000 |

| Death | 11 (57.9 %) | 19 (82.6 %) | 16 (66.7 %) | 0.205 | – | – | – |

| Glucocorticoid | 16 (84.2 %) | 17 (73.9 %) | 20 (83.3 %) | 0.632 | – | – | – |

aAll patients: n = 66, Group 1 = 19, Group 2 = 23, Group 3 = 24.

bAll patients: n = 56, Group 1 = 17, Group 2 = 18, Group 3 = 21.

cAll patients: n = 52, Group 1 = 15, Group 2 = 18, Group 3 = 19.

*Adjusted p-Value.

Groups I, II, and III represented patients with △eGFRcr-cysc %<25 %, 25 %–45 %, and >45 %, respectively.

△eGFRcr-cysc % was defined as △eGFRcr-cysc/mean of eGFRcr and eGFRcysc × 100 %. △eGFRcr-cysc %=

The associations between eGFR and outcome

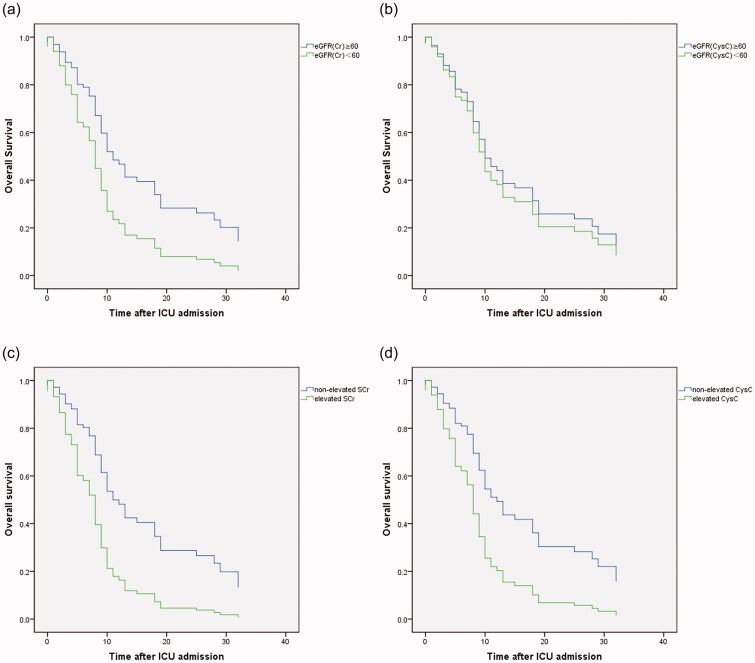

In critically ill group, a total of 56 (73.7 %) patients died in hospital. The median time from illness onset and ICU admission to death was 29 (21–38) days and 9 (5–18) days, respectively (Table 2).Compared with survivors, non-survivors had higher levels of APACHEII, SOFA scores, D-dimer category and inflammatory markers, including WBC, IL-6, IL-8 and hsCRP (Table 3). Univariate and different multivariate Cox proportional hazards models indicated that elevation of D-dimer (HR, 1.145; 95 %CI 1.008–1.987; p = 0.045), IL-6 level (HR, 1.000; 95% CI, 1.000–1.001; p = 0.008), APACHEII score (HR, 1.067; 95% CI, 1.013–1.124; p = 0.014), hypoalbuminemia (HR, 0.944; 95% CI, 0.892–0.998; p = 0.041) as well as reduced eGFRcr (hazard ratio [HR],1.939, 95% confidential intervals (95%CI) 1.078–3.489, p = 0.027) rather than reduced eGFRcysc, were associated with death (Table 6;Table S1,2; Figure 3).

Table 6.

Different multivariate Cox proportional hazards models for risk factors of in-ICU death.

| HR | 95%CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MODEL1a | |||

| Alb | 0.955 | 0.899–1.015 | 0.137 |

| eGFRcr<60 | 2.003 | 1.072–3.742 | 0.029 |

| DD categories | 1.295 | 0.931–1.800 | 0.125 |

| MODEL2a | |||

| Alb | 0.944 | 0.887–1.004 | 0.068 |

| eGFRcysc<60 | 1.173 | 0.684–2.012 | 0.561 |

| DD categories | 1.215 | 0.886–1.664 | 0.227 |

| MODEL3a | |||

| Alb | 0.951 | 0.893–1.013 | 0.120 |

| eGFRcr-cysc<60 | 1.603 | 0.924–2.779 | 0.093 |

| DD categories | 1.236 | 0.899–1.697 | 0.192 |

| MODEL4a | |||

| IL-6 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.001 | 0.356 |

| APACHEII | 1.067 | 1.013–1.124 | 0.014 |

| DD categories | 1.117 | 0.779–1.602 | 0.546 |

| MODEL5a | |||

| IL-6 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.001 | 0.008 |

| DD categories | 1.103 | 0.764–1.592 | 0.601 |

| Vasopressors | 1.772 | 0.887–3.540 | 0.105 |

About 75 patients (55 deaths) were included in this mode.

Figure 3.

The Kaplan–Meier survival curves for critically ill patients divided by reduced eGFRcr (a), reduced eGFRcysc (b), elevated sCr(c) and elevated CysC (d). Reduced eGFRcr (<60 mL/min/1.73 m2) rather than reduced eGFRcysc was associated with death after ICU admission in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Both elevated sCr and elevated CysC were associated with death after ICU admission in critically ill patients with COVID-19.

Figure 4.

Patients with bigger divergence between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc had higher IL6, TNFα levels and APACHEII, SOFA scores. (Critically ill patients were grouped according to the difference ratio (△eGFRcr-cysc%) defined as △eGFRcr-cysc/mean of eGFRcr and eGFRcysc; Groups 1, 2, and 3 represented patients with △eGFRcr-cysc% 0–25%, 25%–45% and >45%, respectively).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to compare the difference between sCr and CysC in the GFR estimation in critically ill patients with COVID-19. We reported a striking divergence between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc which might be affected by the inflammatory condition. In critically ill patients with COVID-19, multiorgan damages were observed including renal involvements [2,5,29]. However, systematic assessment of the kidney function evaluation biomarkers has not been carried out so far.

The ability to accurately quantify GFR in critically ill patients remains challenging [30]. In bedridden critically ill patients who have a continuing loss of muscle mass [31], a parallel decline in sCr may lead to an overestimation of true GFR. In the contrast, Carlier et al. [32] reported that CysC systematically underestimated inulin clearance in critically ill patients. In two independent studies of mixed heterogeneous ICU patients [33] and critically ill children [34], CysC was found to be a poor biomarker for diagnosing AKI. Several studies comparing the performance of sCr and CysC in renal function estimation have gotten conflicting results in ICU patients [15,35,36]. A recent study carried by Sangla et al. [11] compared eGFR using different equations with the measured GFR and found that all equations displayed poor accuracy in the mixed ICU population.

Our data showed a significant divergence up to 24.85 mL/min/1.73 m2 between the median eGFRcr and eGFRcysc in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Twice as many patients had GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 when estimated from CysC compared with GFR estimated from sCr. This finding seemed in line with a previous study carried out in a general ICU which reported this divergence as 44 versus 26 % [36]. They observed that during ICU admission, sCr progressively fell, whereas CysC rose at the same time. Compared with their report, we chose the timepoint of comparison between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc at ICU admission while they made it at ICU discharge. During the initial outbreak of COVID-19, our patients were admitted to ICU at a relatively late phase with critical conditions and rapid progressions because the medical resources as well as the understanding of the newly discovered disease were both in shortage. So it could be explainable why our patients had shown significant divergence between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc at ICU admission.

Inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, TNF-αas well as APACHEII, SOFA scores were potential influencing factors of the divergence between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc in our study. It has been proved serum CysC could act as an inflammation marker in chronic kidney disease [24] and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients [37]. Stevens et al. [19] indicated that higher levels of serum CysC were associated with hsCRP levels and WBC counts. Recently, Chen et al. [38] found the relationship between high CysC levels and severe inflammatory conditions in COVID-19 thus concluded that CysC could act as a potential inflammatory biomarker in COVID-19 patients. Based on these evidences indicating the association between CysC level and inflammation, it is reasonable that inflammatory state increased the divergence between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc. Patients with higher APACHEII scores were suffering more serious conditions and had higher probabilities of inflammatory cytokine storm thus the divergence may be elevated. There were inconsistent results regarding the associations between glucocorticoid and CysC. Risch et al. [39] concluded that glucocorticoid therapy was associated with increased concentration of CysC. Nevertheless, Hüsing et al. [40] observed no difference in CysC concentration among different serum cortisol levels in their ICU patients. In our study, there were no significant difference in glucocorticoid therapy among three groups divided by the divergence degree between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc.

As endogenous biomarkers of renal function, sCr and CysC both indirectly assess GFR. Since the striking difference between eGFRcr and eGFRcysc existed in critically ill patients with COVID-19, it is reasonable to speculate that one or both fail to reflect actual GFR. Evidence suggested that renal impairments were associated with worse prognosis [41–43]. Recently, the relationship between kidney injury and mortality in COVID-19 has also been reported [8,9,44,45]. To a certain extent, the prognosis values of eGFRcr and eGFRcysc could indirectly reflect the ability of renal function assessment. In our study, reduced eGFR-cr other than reduced eGFR-cysc showed significant relativity with death. In contrast to eGFRcysc, CysC itself could serve as a risk factor for mortality. This finding was also consistent with previous studies. In a study of a mixed ICU, Dyanne et al. verified the prognosis value of CysC in the illness severity in critically ill patients [46]. The predictive value of Cys C in the prognosis of COVID-19 patients has also been reported by Yan Li et al. [45] and Dan Chen et al. [38] separately. It seemed interesting that eGFRcysc is a poor predictive factor while CysC itself could be a good predictor of mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Based on the association between inflammatory state and CysC, this result was explainable if we take the severe inflammation state of this special population into account. It is suggested that inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α are positively correlated with disease severity in patients with COVID-19 [47,48]. Lots of patients with severe COVID-19 might suffer a cytokine storm syndrome which is a key factor in developing ARDS and extrapulmonary multiple-organ failure [49–51]. In our study, critically ill patients displayed obvious elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, ferritin, and hsCRP. Given all that, we may reasonably conclude that in critically ill patients with COVID-19 who were suffering a severe inflammation condition, CysC itself showed clinical significance in prognosis as an inflammatory marker but its value in estimating GFR is suspicious with the disturbance of severe inflammation state. For this population, CysC was not recommend to be used in eGFR calculating.

Our study does have several limitations. Being a single center study, the numbers of enrolled patients were limited and our findings would need confirmation in larger groups as well as other age groups. Moreover, we were unable to acquire the measured GFR through iohexol or inulin clearance procedure as a golden standard. On account of the relationship between kidney injury and mortality in COVID-19, we conducted a comparison between the prognostic values of eGFRcr and eGFRcys. In addition, the tests of tubular functions were lacking and we failed to collect enough data from urine protein/creatinine results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we reported a noticeable divergence between the estimated GFR based on sCr and CysC in critically ill patients with COVID-19. The divergence might be affected by the illness severity and inflammatory condition. In critically ill COVID-19 patients with severe inflammatory state, we advocate for caution when using CysC based estimated GFR equations.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all the patients. The authors thank all the medical staff including doctors, nurses, and facilitators who provided care with COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China [81970621 to Yan Qin] and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [3332019029 to Peng Xia].

Author contribution

P. X, Y.L, and Y. Q designed this study. P. X, Y. L drafted this manuscript. P. X and Y.L did all the statistics and draw the figures. P. X, J. M, W.C, Z.L, and Y.Q cared the patients enrolled in this study and provide the original clinical records. P. X and Y.L extracted the clinical data. X. L and Y.Q reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the manuscript in its final form.

Disclosure statement

All authors declared no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 2.Asgharpour M, Zare E, Mubarak M, et al. COVID-19 and kidney disease: update on epidemiology, clinical manifestations, pathophysiology and management. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2020;30(6):19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan L, Chaudhary K, Saha A, et al. AKI in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(1):151–160. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020050615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsch JS, Ng JH, Ross DW, Northwell Nephrology COVID-19 Research Consortium, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;98(1):209–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farouk SS, Fiaccadori E, Cravedi P, et al. COVID-19 and the kidney: what we think we know so far and what we don't. J Nephrol. 2020;33(6):1213–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia P, Wen Y, Duan Y, et al. Clinicopathological features and outcomes of acute kidney injury in critically ill COVID-19 with prolonged disease course: a retrospective cohort. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(9):2205–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Yang X, Yang L, et al. Clinical course and predictors of 60-day mortality in 239 critically ill patients with COVID-19: a multicenter retrospective study from Wuhan, China. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, et al. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97(5):829–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pei G, Zhang Z, Peng J, et al. Renal involvement and early prognosis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(6):1157–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinke T, Moritz S, Beck S, et al. Estimation of creatinine clearance using plasma creatinine or cystatin C: a secondary analysis of two pharmacokinetic studies in surgical ICU patients. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15(1):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sangla F, Marti PE, Verissimo T, et al. Measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate in the ICU: a prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(12):e1232–e1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Kashani K.. Serum creatinine level, a surrogate of muscle mass, predicts mortality in critically ill patients. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(5):E305–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seller-Perez G, Herrera-Gutierrez ME, Maynar-Moliner J, et al. Estimating kidney function in the critically ill patients. Crit Care Res Pract. 2013;2013:721810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baptista JP, Udy AA, Sousa E, et al. A comparison of estimates of glomerular filtration in critically ill patients with augmented renal clearance. Crit Care. 2011;15(3):R139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baptista JP, Neves M, Rodrigues L, et al. Accuracy of the estimation of glomerular filtration rate within a population of critically ill patients. J Nephrol. 2014;27(4):403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel SS, Molnar MZ, Tayek JA, et al. Serum creatinine as a marker of muscle mass in chronic kidney disease: results of a cross-sectional study and review of literature. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2013;4(1):19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Udy AA, Baptista JP, Lim NL, et al. Augmented renal clearance in the ICU: results of a multicenter observational study of renal function in critically ill patients with normal plasma creatinine concentrations. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(3):520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoste EA, Damen J, Vanholder RC, et al. Assessment of renal function in recently admitted critically ill patients with normal serum creatinine. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association. Eur Renal Assoc. 2005;20(4):747–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, et al. Factors other than glomerular filtration rate affect serum cystatin C levels. Kidney Int. 2009;75(6):652–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knight EL, Verhave JC, Spiegelman D, et al. Factors influencing serum cystatin C levels other than renal function and the impact on renal function measurement. Kidney Int. 2004;65(4):1416–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhai JL, Ge N, Zhen Y, et al. Corticosteroids significantly increase serum cystatin C concentration without affecting renal function in symptomatic heart failure. Clin Lab. 2016;62(01 + 02/2016):203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying P, Yang C, Wu X, et al. Effect of hydrocortisone on the 28-day mortality of patients with septic acute kidney injury. Ren Fail. 2019;41(1):794–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsushita H, Tanaka R, Suzuki Y, et al. Effects of dose and type of corticosteroids on the divergence between estimated glomerular filtration rates derived from cystatin C and creatinine. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45(6):1390–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muslimovic A, Tulumovic D, Hasanspahic S, et al. Serum cystatin C - marker of inflammation and cardiovascular morbidity in chronic kidney disease stages 1-4. Mater Sociomed. 2015;27(2):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borges RL, Hirota AH, Quinto BM, et al. Is cystatin C a useful marker in the detection of diabetic kidney disease? Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;114(2):c127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng Y, Wang L, Hou Y, et al. The influence of glycemic status on the performance of cystatin C for acute kidney injury detection in the critically ill. Ren Fail. 2019;41(1):139–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Health Commission of China: Guideline of management of COVID-19 (5th trial edition). Available at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/3b09b894ac9b4204a79db5b8912d4440.shtml

- 28.Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, for the Sepsis Definitions Task Force, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):775–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin S, Orieux A, Prevel R, et al. Characterization of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13(3):354–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bragadottir G, Redfors B, Ricksten SE.. Assessing glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury-true GFR versus urinary creatinine clearance and estimating equations. Crit Care. 2013;17(3):R108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joskova V, Patkova A, Havel E, et al. Critical evaluation of muscle mass loss as a prognostic marker of morbidity in critically ill patients and methods for its determination. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50(8):696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlier M, Dumoulin A, Janssen A, et al. Comparison of different equations to assess glomerular filtration in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(3):427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Royakkers AA, Korevaar JC, van Suijlen JD, et al. Serum and urine cystatin C are poor biomarkers for acute kidney injury and renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(3):493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamed HM, El-Sherbini SA, Barakat NA, et al. Serum cystatin C is a poor biomarker for diagnosing acute kidney injury in critically-ill children. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2013;17(2):92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravn B, Rimes-Stigare C, Bell M, et al. Creatinine versus cystatin C based glomerular filtration rate in critically ill patients. J Crit Care. 2019;52:136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ravn B, Prowle JR, Martensson J, et al. Superiority of serum cystatin C over creatinine in prediction of long-term prognosis at discharge from ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(9):e932–e940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang M, Li Y, Yang X, et al. Serum cystatin C as an inflammatory marker in exacerbated and convalescent COPD patients. Inflammation. 2016;39(2):625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen D, Sun W, Li J, et al. Serum cystatin C and coronavirus disease 2019: a potential inflammatory biomarker in predicting critical illness and mortality for adult patients. Mediat Inflamm. 2020;2020:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Risch L, Herklotz R, Blumberg A, et al. Effects of glucocorticoid immunosuppression on serum cystatin C concentrations in renal transplant patients. Clin Chem. 2001;47(11):2055–2059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herget-Rosenthal S, Marggraf G, Hüsing J, et al. Early detection of acute renal failure by serum cystatin C. Kidney Int. 2004;66(3):1115–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liosis S, Hochadel M, Darius H, et al. Effect of renal insufficiency and diabetes mellitus on in-hospital mortality after acute coronary syndromes treated with primary PCI. Results from the ALKK PCI Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2019;292:43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper WA, O’Brien SM, Thourani VH, et al. Impact of renal dysfunction on outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery: results from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Adult Cardiac Database. Circulation. 2006;113(8):1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hailpern SM, Cohen HW, Alderman MH.. Renal dysfunction and ischemic heart disease mortality in a hypertensive population. J Hypertens. 2005;23(10):1809–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Figliozzi S, Masci PG, Ahmadi N, et al. Predictors of adverse prognosis in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;50(10):e13362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Yang S, Peng D, et al. Predictive value of serum cystatin C for risk of mortality in severe and critically ill patients with COVID-19. WJCC. 2020;8(20):4726–4734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dalcomune DM, Terrao J, Porto ML, et al. Predictive value of cystatin C for the identification of illness severity in adult patients in a mixed intensive care unit. Clin Biochem. 2016;49(10-11):762–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen L, Liu HG, Liu W, et al. Analysis of clinical features of 29 patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Tubercul Respir Dis. 2020;43:E005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. The Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brigham KL. Lower tidal volume ventilation and plasma cytokine markers of inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2005;7(5):327–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Ma S.. The cytokine storm and factors determining the sequence and severity of organ dysfunction in multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(6):711–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]