Abstract

Objectives:

Home-based mindfulness practice is a common component of formal mindfulness training (MT) protocols. Obtaining objective data from home-based mindfulness practice is challenging. Interpreting associations between home-based mindfulness practice and clinically impactful outcomes is complicated given the variability in recommendations in length, frequency, and type of practice. In this exploratory study, adherence to home-based practices of Mindfulness-Based Resilience Training (MBRT) was studied in order to evaluate associations with clinical outcomes.

Methods:

Home practices from 24 (92% male, non-Hispanic white, aged M = 43.20 years) law enforcement officers (LEOs) from the urban Pacific Northwest enrolled in a feasibility and efficacy trial of MBRT were studied using an objective tracking device and self-report data. Outcomes included adherence to home-based mindfulness practices and self-reported aggression.

Results:

Participants completed 59.12% of the frequency amount of practice assigned in the MBRT curriculum. Frequency of practice was associated with decreased aggression, adjusted R2 = .41, F(3,23) = 6.14, p = .004. Duration of practice also predicted decreased aggression, adjusted R2 = .33, F(3,23) = 4.76, p = .011.

Conclusions:

Home-based MBRT practices for LEOs, even at low rates of adherence, may reduce aggression. MTs may show beneficial effects for other populations presented with challenges to engage in regular MT practices.

Mindfulness is conceptualized as an interactive and multifaceted process involving the dynamic interplay of several cognitive, mutually reinforcing, processes (Christopher, Christopher, & Charoensuk 2009). First and foremost of these cognitive processes is the deliberate focus of attention and a clear awareness of one’s inner and outer worlds, including thoughts, emotions, sensations, behaviors, or surroundings as they exist at any given moment. A second important process of mindfulness includes a receptive, nonreactive stance that allows for the de-automatization of habitual reactions to the present moment and the associated secondary appraisals, predictions, analyses, critics, or judgements about what has or is taking place. This watchful, nonreactive awareness neither suppresses the content of the present moment experience, nor habitually reacts. Instead, through practice, a person develops a basic knowing of what is happening in the present moment, which subsequently, may lead to a discriminative ability to discern skillful from unskillful thoughts and behaviors (Anālayo 2011). Mindfulness is conceptualized as a dispositional trait in which a person is able to pay attention to the present moment, on purpose, and with a nonjudgmental and nonreactive attitude (Kabat-Zinn 1990). Mindfulness is also conceptualized as a mental training in which a person engages in exercises to increase dispositional mindfulness. Recent studies suggest that mindfulness training (MT) results in cognitive (Chiesa, Calati, & Serreti 2011), affective (Gu, Strauss, Bond, & Cavanagh 2015), behavioral (De Vibe, Bjørndal, Fattah, Dyrdal, Halland, & Tanner-Smith 2017; Ruffault et al. 2017), and neural changes (Hölzel, Carmody, Vangel, Congleton, Yerramsetti, Gard, & Lazar 2011; Hölzel, Lazar, Gard, Schuman-Olivier, Vago, & Ott 2011; Jha, Krompinger, & Baime 2007; Lutz, Jha, Dunne, & Saron 2015), and has evidenced lasting effects (Carlson, Tamagawa, Stephen, Drysdale, Zhong, & Speca 2016; Hansen, Kesmodel, Kold, & Forman 2017).

Regular mindfulness practice may be key to building a skilled, mindful mind (Gu et al. 2015; Visted, Vøllestad, Nielsen, & Nielsen 2015) and is considered a core element of most MTs. Many mindfulness-based programs (MBPs) include regular assigned home mindfulness practice as part of the training (e.g., Kabat Zinn 1990; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale 2002); however, less is known about the potential differential effects of frequency, length, and type of mindfulness practices on specific outcomes and differing populations. Frequency and consistency of mindfulness home practice has been positively related to levels of mindfulness (Baer et al., 2008), resilience (Jha, Morrison, Parker, & Stanley 2017) and well-being (Parsons, Crane, Parsons, Fjorback, & Kuyken 2017), and negatively related to levels of anxiety, stress, and poor mental health outcomes (Hoge et al. 2017). Other studies, however, have not found a statistically significant relationship between frequency, duration, or type of home practice and clinical outcomes (Quach, Gibler, & Mano 2017; Lloyd, White, Eames, & Crane 2017; Ribeiro, Atchley & Oken, 2018; Vettese, Toneatto, Stea, Nguyen, & Wang 2009). These mixed results highlight the need to explore dose effects, as well as potential differential effects of specific types of mindfulness practice needed to achieve and maintain clinical benefits following MT interventions.

Methods used to measure aspects of home mindfulness practice vary in accuracy, which may partially account for differences between studies. In a recent systematic review, Lloyd et al. (2017) found various methods including electronic loggers (Gross et al. 2011) and home-practice logs/diaries (Cash et al. 2014). Inherent in retrospective self-reports is the potential inaccuracy of memory or documentation of experience over the past day, week, or month (Dobkin & Zhao 2011; Moore, Depp, Wetherell, & Lenze 2016). Wahbeh, Zwickey, and Oken (2011) had MT participants subjectively and objectively track mindfulness practice using daily logs and an objective meditation practice app (iMINDr) installed on an iPod touch, respectively. Participants endorsed more retrospective mindfulness practice using daily logs than they actually practiced based on objective tracking data, illustrating the potential limited reliability and validity of self-reporting mindfulness practice.

Guidance on amount of home practice and resources provided to support home practice are also highly variable, further limiting our understanding of the dose-response curve (Lloyd et al. 2017; Ribeiro, Atchley, & Oken 2018). Mirroring pioneer MBPs such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, Lipworth, & Burney 1985) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT; Segal, Williams, Teasdale, & Gemar 1996), many MT protocols recommend participants engage in 45–60 minutes of daily home mindfulness practice during the course of the training, with specific suggestions of which practices to complete. Other MT protocols, however, suggest 20 minutes of daily practice, 5 days a week, with no specific recommendations for types of practice (King et al. 2013). In a recent meta-analysis, Parsons et al. (2017) found that across 43 MBSR and MBCT studies, participants reported completing only 60% of assigned formal mindfulness home-practice during the intervention period. Results suggest the minimum practice required to achieve clinical benefits may be significantly lower than currently hypothesized. Given that the time commitment required to engage in home practice is a common barrier for new practitioners (Dutton, Bermudez, Matas, Majid, & Myers 2013), identifying evidence-based dose-response curves and differential effects of practice type may be crucial to support long-term treatment adherence and enactment.

A dearth of published studies reporting specific types of mindfulness practiced, and adherence rates to these practices, may also account for variability in outcomes. Different mindfulness practices have been found to have differential effects (Baer, 2009; Colgan Christopher, Michael, & Wahbeh 2016; Colgan, Wahbeh, Pleet, Besler, & Christopher 2017; Davidson & Kaszniak 2015). For example, in a randomized control trial (RCT), 100 veterans were assigned to one of four arms: body scan, mindful breathing, slow breathing, or sitting quietly control group. Veterans who attended the six-week slow breathing course were significantly more likely to report enhanced quality of sleep, when compared to veterans who were assigned to the body scan or sitting quietly arm. Veterans who attended a six-week body scan course were significantly more likely to report reductions in anger when compared to participants assigned to a mindful breathing, slow breathing, or sitting quietly group (Colgan et al. 2017). In another RCT, mindful yoga was associated with greater increases in psychological well-being than a formal sitting meditation or body scan practice. Sitting meditation and mindful yoga were both associated with greater improvement in emotion regulation than body scan, and sitting meditation was associated with greater increases in the tendency to take a non-evaluative stance toward observed stimuli than the body scan (Feldman, Greeson, & Senville, et al. 2010). Collectively, these results point to the relevance of exploration of how specific outcomes are related to particular practices and populations.

Research suggests that due to poor physical and mental health, high-stress cohorts have to potential to greatly benefit from MT (Creswell & Lindsay 2014; Lindsay & Creswell 2017); however, rates disengagement and attrition are high (Khoury, Sharma, Rush, & Fournier 2015). Qualitative studies have identified key hindrances in engaging with mindfulness practices: 1) difficulty understanding the purpose of the mindfulness practice; 2) lack of time for long practices; 3) emerging negative thoughts; and 4) becoming self-critical. Identified key facilitators of a mindfulness practice included: 1) the need for stress reduction techniques; 2) shorter practices; and 3) increased sense of agency over thoughts (Banerjee, Cavanagh & Strauss 2017; Martinez et. al. 2015). Taken together, high stress cohorts are an important population in which to study the differential impact of frequency, duration, and specific types of MT on health-related outcomes.

Policing is one of the most highly stressful occupations (Violanti, Andrew, Burchfiel, Dorn, Hartley, & Miller 2006; Violanti, Slaven, Charles, Burchfiel, Andrew, & Homish 2011). Unpredictable exposures to critical incidents, violence, chronic stress, job dissatisfaction, and societal expectations for optimal performance can create a toxic work environment and lead to significant negative mental health and behavioral outcomes for law enforcement officers (LEOs; Avdija 2014; McCrathy & Atkinson 2012; O’Hara, Violanti, Levenson, & Clark 2013). These negative outcomes also impact the communities officers serve; psychologically impaired LEOs are more likely to use excessive force (Kop, Euwema, & Schaufeli 1999; Kurtz, Zavala, & Melander 2015; Nieuwenhuys, Savelsbergh, & Oudejans, 2012) and be aggressive toward suspects (Can & Hendy 2014; Gershon, Barocas, Canton, Li, & Vlahov 2009; Griffin & Bernard 2003; Kurtz et al.2015; Rajaratnam et al.2011).

Mindfulness-Based Resilience Training (MBRT) is an eight-week MT tailored to first responders and other high-stress cohorts (Christopher et al., 2016). MBRT was designed to enhance resilience for LEOs in the context of acute and chronic stressors inherent to policing. Based on a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (Kabat-Zinn, 1990) framework, MBRT was delivered in eight weekly 2-hour sessions with an extended 6-hour class in the seventh week. Content and language were adapted for a LEO population. The primary focus of the curriculum was learning strategies to manage stressors inherent to police work, including critical incidents, job dissatisfaction, and public scrutiny, as well as interpersonal, affective and behavioral challenges common to LEOs’ lives (Christopher et al., 2016). In a recent RCT, MBRT participants experienced improvement in physiological and psychological outcomes, including reduced aggression, when compared to no intervention control participants (Christopher et al., 2018). Although some literature suggests MT can reduce aggression (Fix & Fix 2013), little is known about which specific practices may differentially impact aggression, particularly among a high-stress cohort such as LEOs. Therefore, the primary aim of this exploratory study was to assess the differential impact of a variety of mindfulness practices on aggression among LEOs using an objective tracking device.

Method

Participants

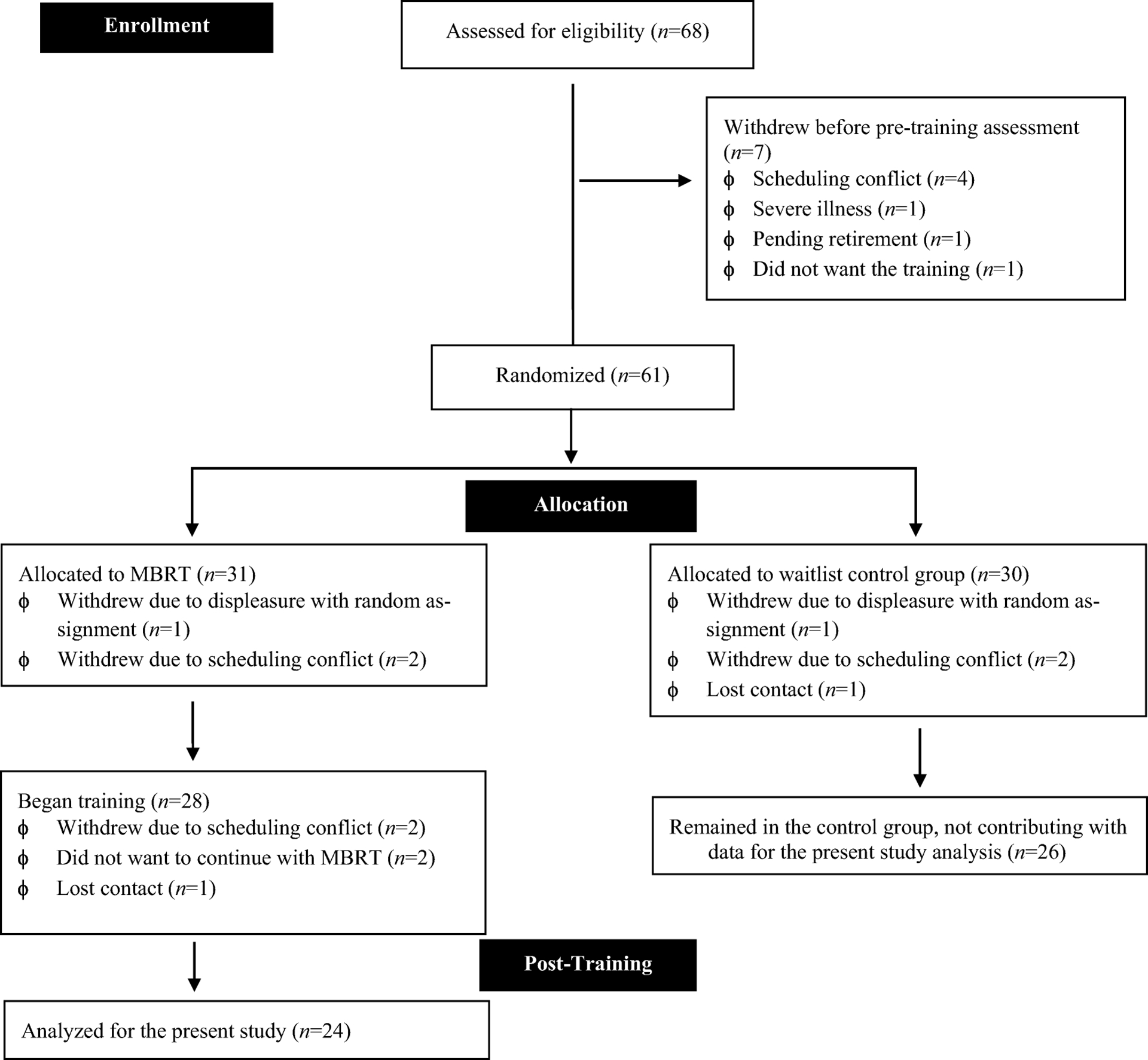

Data in the present study were collected from an RCT investigating the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of MBRT (Christopher et al., 2018). A total of 61 participants were recruited from law enforcement agencies across a metropolitan area in the Pacific Northwest US through emails, fliers, and presentations. To be eligible for study participation, interested individuals had to be a full-time sworn LEO with no previous exposure to MBRT or a similar mindfulness course (for more information see Christopher et al.,2018). Of the 31 participants assigned to the MBRT group, 24 completed the study. One participant withdrew due to displeasure with random assignment, four withdrew due to scheduling conflict, and 2 chose not to continue with MBRT (for the Participant flow chart see Figure 1). The 24 participants who completed the study constituted a predominantly male (92%), non-Hispanic white (83%) and relatively young adult sample (M = 43.20 years; SD = 5.26). These characteristics reflect the expected demographics of the target population. Table 1 shows the full sample characterization, including average years on the force and rank.

Fig 1.

Participant Flow Chart

Table 1.

Demographics

| N | 24 | Race | |

| Age (SD) | 43.20 (5.26) | White | 20 (83%) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 2 (8%) | Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander | 1 (3%) |

| Male | 23 (92%) | Native American / Alaskan | 0 (0%) |

| Rank | Asian | 1 (3%) | |

| Officer | 9 (29%) | Multi-racial | 1 (3%) |

| Deputy | 3 (10%) | Other | 0 (0%) |

| Criminalist | 0 (0%) | ||

| Detective | 3 (10%) | Ethnicity | |

| Sergeant | 6 (19%) | Non-Hispanic / Non-Latino | 30 (97%) |

| Lieutenant | 3 (10%) | Hispanic / Latino | 1 (3%) |

| Commander | 1 (3%) | ||

| Captain | 4 (13%) | ||

| Other | 2 (6%) | ||

| Years on the Job (SD) | 18.5 (6.98) |

Procedures

The Pacific University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. Participants meeting study criteria were scheduled for an initial pre-training assessment between January and March 2016, during which they provided written informed consent and completed all baseline measures via computer. Participants were subsequently randomly assigned using permuted-block randomization (1:1 ratio) with stratification (sex and age) to MBRT or the no intervention control group. As our focus in this study was to explore adherence to practice, we only analyzed the outcomes of the MBRT group. All 24 participants in the present study completed baseline and post-MBRT assessments and were study completers (i.e., attended a minimum of 5 out of 8 MBRT classes). All lab visits were identical; participants completed a computer-administered battery of computerized tasks and self-report measures. To minimize the effects of demand characteristics in this sample, participants were not informed about the objective of the study. Additionally, to help facilitate honest responding to self-report measures, participants were informed that the research team obtained a certificate of confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health to further ensure their privacy.

Mindfulness Training.

MBRT was designed to enhance resilience for LEOs in the context of acute and chronic stressors inherent to policing. MBRT was delivered in eight weekly 2-hour sessions with an extended 6-hour class in the seventh week. Sessions contained experiential and didactic exercises, including body scan, sitting and walking meditations, mindful movement, and group discussion. Content and language were adapted for a LEO population. The primary focus of the curriculum was learning strategies to manage stressors inherent to police work, including critical incidents, job dissatisfaction, and public scrutiny, as well as interpersonal, affective and behavioral challenges common to LEOs’ lives (Christopher et al., 2016).

Measures

The parent RCT included self-report, computerized, and physiological measures (Christopher et al.,2018). The computerized and physiological data are not within the scope of our current analyses, and methodology and results concerning the collection of these data are not presented in this paper. The present study is focused on the relationship between duration, frequency, and type of mindfulness practice, and changes in aggression levels among LEOs; therefore, only measures regarding this outcome were included in analyses.

Aggression.

The Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire-Short Form (BPAQ-SF; Bryant & Smith 2001) is a 12-item, Likert-type scale of aggression derived from the 29-item BPAQ (Buss & Perry 1992). The BPAQ-SF is the most widely used measures of aggression and was developed to assess four dispositional subtraits of aggression: physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility. The BPAQ-SF ranges from 1–5, with higher scores indicating greater aggression. In the full LEO sample gathered for the parent study (Christopher et al., 2018), the BPAQ-SF demonstrated good internal inconsistency at both pre- (α= 0.83) and post- (α= 0.83) MBRT.

Adherence to meditation practice.

Participants in the MBRT group received an iPod Touch (Apple, Inc.) for the study period. Each iPod contained guided formal and informal mindfulness practices (see Table 2). Together with the mindfulness tracks, each iPod was installed with iMINDr, a software application developed to track participants’ frequency, duration and selection of practice (Wahbeh et al. 2011; Wahbeh, Lane, Goodrich, Miller, & Oken 2014). The iMINDr app thus tracked time, length, track, and date of listening each guided meditation.

Table 2.

Type, Frequency, and Duration of Weekly Assigned Mindfulness Practice in a Mindfulness-Based Resilience Training

| Formal Sitting Meditation Cluster | Frequency | Duration | Bodily Awareness Cluster | Frequency | Duration | Present Moment Awareness Cluster | Frequency | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week one | Sitting Practice | 3 | 10 min. | Body Scan | 3 | 20 min. | Mindful Pause | 7 | 3 min. |

| Week two | Sitting Practice | 2 | 10 min. | Body Scan | 2 | 20 mm. | Mindful Pause | 7 | 3 min. |

| Mindful Movements | 2 | 18 min. | |||||||

| Week three | Sitting Practice | 3 | 10 min. | Body Scan | 1 | 20 min. | Mindful Pause | 7 | 3 min. |

| Mindful Movements | 3 | 18 min. | |||||||

| Week four | Sitting Practice | 3 | 10 min. | Mindful Movements | 3 | 18 min. | Mindful Pause | 14 | 3 min. |

| Mindful Encounters | 2 | 26 min. | |||||||

| Week five | Sitting Practice | 3 | 10 min. | Mindful Movements | 2 | 18 min. | Mindful Pause | 14 | 3 min. |

| Mindful Encounters | 2 | 26 min. | |||||||

| Attention and Recovery | 2 | 15 min. | |||||||

| Week six | Sitting Practice | 2 | 10 min. | Mindful Movements | 2 | 18 min. | Mindful Pause | 14 | 3 min. |

| Mindful Encounters | 2 | 26 min. | |||||||

| Attention and Recovery | 2 | 15 min. | |||||||

| Week Seven | 20 minutes a day of your choice |

Data Analyses

Paired t-tests were used to assess pre- to post-MBRT change on the BPAQ-SF. To analyze home practice data, raw duration and frequency of each mindfulness practice was downloaded from the iMINDr software and analyzed by visual inspection. Meditations that were listened to for less than 10 seconds were labeled as “sorting” and excluded from analyses. We created five variables using iMINDr data: 1) duration is the number of seconds practiced for each guided meditation, 2) total duration is the number of seconds practiced across all guided meditations, 3) frequency is the number of times practiced for each guided meditation, 4) total frequency is the number of times practiced across all guided meditations, and 5) total days is the sum of days dedicated to practice. Adherence data were collected only during the 8-week MBRT intervention. Each adherence variable was square root transformed due to non-normality (i.e., positive skewness).

To create measures of change across the training, we calculated a residualized change score by regressing the posttreatment outcome variable (i.e., aggression) on the same variable at baseline and saved the standardized residuals. Pearson’s zero-order correlations using the residualized change scores were used to investigate which guided mindfulness practices were associated with changes in aggression from pre- to post-MBRT. To determine which practices were predictive of improvements in aggression relative to similarly themed practices, three guided mindfulness practice clusters were created (i.e., bodily awareness, present moment awareness, and formal sitting meditation). The frequency and duration of each cluster were used to predict residualized change in aggression for a total of six multiple linear regression analyses. In each regression, the three practices within a meditation practice cluster were entered simultaneously as predictors of residualized change in aggression. Additionally, to further assess the impact of different levels of meditation practice on aggression, we divided each of the clusters for both frequency and duration into tertiles: low, medium, and high. We then conducted ANOVAs with aggression as the dependent variable and the tertile adherence groups as the independent variables.

Results

Mindfulness Practice Adherence Characteristics Among LEOs

Participants were introduced to a variety of guided meditation practices during the 8-week MBRT intervention and instructed to complete a minimum of 30 minutes of daily practice (see Table 2 for guided meditation practices assigned weekly). Out of 56 days of potential practice (i.e., 8-week intervention), on average, participants engaged in 14.44 days of practice (SD = 11.24). Each of the 24 participants practiced at least some of the 10 practices, with a total frequency of 473 and a mean of 19.7 practices per participant (SD = 19.36). Overall, they practiced 59.12% of the assigned frequency of practice in the MBRT curriculum. Altogether, participants listened to 36.17 (SD = 4.59) minutes of audio guided practices on average per week. The relative percent of the sum of time participants listened to each of the audio-guided practices is displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Frequency of Time Listened to Each Audio-guided Practice

| Practice | Number of times listened each practice | Relative percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Mindful Movement | 61 | 13 |

| Mindful Pause | 96 | 20 |

| Mountain Meditation | 7 | 1 |

| Body Scan | 136 | 29 |

| Sitting Meditation | 66 | 14 |

| Mindful Exercise | 10 | 2 |

| Silence Track | 26 | 5 |

| Attention and Recovery | 18 | 4 |

| Lake Meditation | 17 | 4 |

| Mindful Encounter | 36 | 8 |

Consistent with MBRT instructions for home practice, body scan (29%), mindful pause (20%), and sitting meditation (14%) were the most frequently practiced throughout the training when compared to other options. To explore potential covariates using zero-order Pearson correlation coefficients, we examined whether LEO job rank, number of years on the job, and age were correlated with the frequency and duration of guided meditation practices. All correlations were non-significant (p’s > .05).

Correlations Between Aggression and Mindfulness Practice

Results from the parent RCT can be obtained in a previous publication (Christopher et al., 2018). As expected, the mean BPAQ-SF scores were significantly reduced from pre- (M = 1.87, SD = .59) to post- (M = 1.47, SD = .43) MBRT, t(23) = 3.94, p = .004.

Frequency.

Reduced aggression (i.e., residualized change scores) was significantly correlated with the total frequency of guided meditation practice r(22) = −.49, p = .017 and the total number of days practicing throughout the training, r(22)= −.52, p = .009, suggesting both frequency and amount of days dedicated to practice were related to reduced aggression. When clustered in themed groups, reduced aggression was significantly correlated with frequency of bodily awareness r(22) = −.68, p <.001, formal sitting r(22) = −.44, p < .032. When considering specific practices, reduced aggression was significantly correlated with frequency of body scan r(22) = − .69, p < .001, sitting meditation r(22) = −.52, p = .011, mindful exercise r(22) = −.42, p <.042, lake meditation r(22)= −.51, p = .012, and mindful encounter r(22) = −.42, p =.042.

Duration.

Reduced aggression was significantly correlated with total duration of guided meditation practice r(22) = −.51, p = .02. At the cluster level, reduced aggression was correlated with duration of bodily awareness r(22) = −.60, p = .002 and formal sitting r(22) = −.53, p = .008. When considering specific practices, reduced aggression was correlated with duration of body scan, r(22) = −.67, p < .001, sitting meditation, r(22) = −.44, p = .032, and lake meditation, r(22) = −.48, p < .05 (see Table 4 for all correlations).

Table 4.

Correlations Between Mindfulness Practices and Residualized Change in Aggression

| Frequency | Duration | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| r | r | ||

| Total number of days | −.52** | ------ | |

| Total frequency | −.49* | ------ | |

| Total duration | ------ | −.51* | |

| Bodily awareness | −.68*** | −.65** | |

| Body scan | −.69*** | −.67*** | |

| Mindful movement | −.20 | −.21 | |

| Mindful Exercise | −.42* | −.40 | |

| Formal sitting | −.44* | −.53** | |

| Sitting meditation | −.52* | −.44* | |

| Lake meditation | −.51* | −.48* | |

| Mountain meditation | −.20 | −.18 | |

| Present moment awareness | −.40 | −.35 | |

| Mindful pause | −.39 | −.34 | |

| Mindful encounters | −.42* | −.30 | |

| Attention and Recovery | −.37 | −.32 |

Note. All meditation practice variables were square root transformed.

p < .05;

p <. 01;

p < .001.

Frequency and Duration of Mindfulness Practice Predicting Aggression

Frequency.

Frequency of bodily awareness cluster practices (i.e., body scan, mindful movement, and mindful exercise) predicted reduced aggression, adjusted R2 = .41, F(3,23) = 6.14, p =.004. At the individual practice level, only the body scan significantly predicted reduced aggression, β = −.63, SE = .111, p = .003 when controlling for mindful movement and exercise. In the second regression, frequency of formal sitting meditation cluster practices (i.e., sitting meditation, lake meditation, and mountain meditation) also predicted reduced aggression, adjusted R2 = .32, F(3,23) = 4.48, p =. 015, with sitting meditation being the only statistically significant individual practice predictor, β = −.53, SE = .195, p = .041 when controlling for lake and mountain meditation. The frequency of present moment awareness cluster practices did not predict reduced aggression.

Duration.

The total duration of bodily awareness cluster practices significantly predicted reduced aggression, adjusted R2 = .33, F(3,23) = 4.76, p = .011. At the individual practice level, only body scan significantly predicted reduced aggression, β = −.56, SE = .003, p < .05 when controlling for mindful movement and exercise. In the second regression, duration of formal sitting meditation cluster practices predicted reduced aggression, adjusted R2 = .23, F(3,23) = 3.26, p = .043; however, no individual practices were statistically significant predictors, ps > .05. Lastly, duration of present moment awareness cluster practices did not predict reduced aggression, p > .05 (see Table 5 for all regressions).

Table 5.

Frequency and Duration of Mindfulness Practices Predicting Residualized Change in Aggression

| Frequency | Duration | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔR2 | F | df | β | beta | t | ΔR2 | F | df | β | beta | t | ||

| Bodily awareness | .412 | 6.145** | 3 | .33 | 4.768* | 3 | |||||||

| Body scan | −.378 | −.636 | −3.403** | −.10 | −.564 | −2.885** | |||||||

| Mindful movement | .056 | .069 | .369 | .001 | .036 | .199 | |||||||

| Mindful exercise | −.138 | −.159 | −.791 | −.021 | −.177 | −.933 | |||||||

| Formal sitting meditation | .32 | 4.485* | 3 | .32 | 3.261* | 3 | |||||||

| Sitting meditation | −.428 | −.536 | −2.191* | −.010 | −.292 | −1.431 | |||||||

| Lake meditation | −.517 | −.362 | −1.872 | −.029 | −.516 | −1.883 | |||||||

| Mountain meditation | .208 | .255 | 1.100 | .016 | .019 | .879 | |||||||

| Present moment awareness | .097 | 1.784 | 3 | 0.29 | 1.232 | 3 | |||||||

| Mindful pause | −.125 | −.164 | −.579 | −.008 | −.015 | −.518 | |||||||

| Mindful encounters | −.226 | −.260 | −.965 | −.005 | −.193 | −.727 | |||||||

| Attention and recovery | −.146 | −.115 | −.406 | −.005 | −.114 | −.379 | |||||||

Note. All variables were square root transformed,

p < .05;

p <. 01;

p < .001.

We also conducted ANOVAs to assess the differences between low, medium, and high tertile rates of meditation practice frequency and duration on levels of aggression. Results revealed no significant main effect (all p > .10).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated frequency, duration, and type of home mindfulness practice among LEOs, a highly stressed and vulnerable population. This was an exploratory study, in which the primary goals were to further our understanding of 1) which practices are most utilized among this population, and 2) the differential impact of frequency and duration of practice on aggression. Overall, our findings demonstrated the differential impact of specific practices among LEOs.

Despite inconsistent and sporadic adherence, frequency of practices was relatively high. Our sample reported engaging in 59.12% of assigned practices, an amount that was significantly correlated to reductions in aggression. This result is consistent with a recent meta-analysis of MBP home practice, in which participants engaged, on average, in 60% of the assigned homework (Lloyd et al. 2017). In this sense, LEO adherence rates were similar to the general population. Considering our participants practiced inconsistently throughout the training, results suggest this population may have a potential preference for an irregular style of practice over a stable one. This may be related to the inconsistent job-related stress of an LEO or the irregular work schedules. Regular, versus sporadic, meditation practice has been predictive of higher levels of mindfulness, indicating that regularity may be the most effective way to enhance mindfulness levels (Bergomi, Tschacher, & Kupper 2015); However, our positive results suggest that even sporadic practice may lead to beneficial outcomes. Factors such as awareness of highly stressful future events (e.g., an extended shift or the probability of riots) and high levels of burnout may suggest that sporadic, but concentrated, practice may be more feasible, and potentially more effective, for this population. Future studies are needed to explore the differences in the effects of regular, verses concentrated sporadic, practice among LEOs.

Total duration of weekly meditation practice was considerably below expectations in this sample. Although participants were instructed to meditate for 30 minutes a day, they practiced an average of 36.17 (SD = 4.59) minutes per week. Because there was a large range in amount of practice between participants, we wondered if higher levels of practice would differential impact results. Our attempt to compare aggression outcomes among participants with low, medium and high levels of adherence (frequency and duration) did not lead to significant results. It is likely that partitioning our small sample underpowered our analysis, restricting further considerations. Despite that, total listening time to guided practices across the sample was significantly correlated to reduced aggression. This result reinforces the idea of behavioral benefits, even with limited adherence to practices.

Types of Practices and Their Relationship to Aggression

Body scan, sitting meditation, mindful pause, and mindful movement were the most frequently practiced, accounting for 76% of the total frequency of practices. This result was expected since these four practices are most frequently recommended in the MBRT protocol (see Table 2). Frequency with which participants engaged in these practices is possibly reflective of the population’s preferences. For example, the practice of the mindful pause was assigned to participants 58 times throughout the training (about 7 to 14 times/week), but participants endorsed practicing only 6% of the assigned frequency (about 4 times/week). The body scan, on the other hand, was practiced 94% of the assigned frequency. These results may indicate a preference for some practices over others, due to either practical reasons (e.g., lack of time, forgetfulness) or perceived effectiveness. Participants endorsed the body scan and other bodily-related practices as most helpful (Bergman et al. 2018, not published), suggesting this as a particularly feasible and relevant practice for highly stressed cohorts.

Frequency and Duration of Specific Practices

Frequency and duration of the bodily awareness cluster (body scan, mindful movement, and mindful exercise) predicted 41% and 33% of variance in reduced aggression respectively, but only body scan predicted changes at the individual level for both frequency and duration. These results suggest the relevance of somatic-oriented practices when targeting aggression. The body scan is an attention-focusing practice designed to increase interoceptive awareness and acceptance (Dreeben, Mamberg, & Salmon 2013). As a somatic-based exercise, it provides the focus on the body as the most concrete aspect of present moment experience. It is one of the first practices taught in most MBPs and has been reported to be perceived as helpful and enjoyable by stressed samples (Ribeiro, et al. 2018). In a four-arm six-week MT RCT with PTSD veterans, participants in the body scan arm reported significantly greater reductions in anger when compared to participants assigned to a mindful breathing, slow breathing, or sitting quietly group (Colgan et al. 2017). Current results provide additional support for the suggested relationship between the body scan practice and reductions in anger and related behaviors such as aggression. Increased awareness of bodily sensations may enhance the ability to manage physiological responses to intense arousal, thereby, diminishing negative outcomes.

In the curent study, both frequency and duration of formal sitting meditation cluster (i.e., sitting meditation, lake meditation, and mountain meditation) was associated with reduced aggression, accounting for 32% and 23%, respectively, of the variance. Despite the significant negative correlation between both the frequency and duration of the lake meditation practice and aggression, only frequency of sitting meditation emerged as a significant predictor of the change in outcome. Sitting meditation is one of the most popular forms of formal mindfulness, requiring higher ability to focus and redirect the mind, and is usually perceived as a more complex practice than the body scan and present moment awareness practices (Anālayo 2011). Previous studies exploring differential effects of sitting meditation have found that these types of practices are associated with greater improvements in emotion regulation and non-judgment, when compared to the body scan practice (Feldman et al. 2010).

Finally, despite the mindful pause being the second most frequent practice, the present moment awareness cluster (i.e., mindful pause, mindful encounters, and attention and recovery practice) did not predict reduced aggression. As an individual practice, the frequency of mindful encounters was significantly correlated with reduced aggression but did not emerge as a significant predictor. Although these practices are devoted to the cultivation of awareness of present moment emotions, thoughts, and other physiological experiences throughout the day, they demonstrated little impact on aggression. It is possible that a higher frequency and duration of this type of practice is needed to impact aggression, or the intensity of these feelings needed longer and more structured practices, such as body scan and sitting meditations, to be managed.

Aggressive behavior can be challenging in any population, but especially problematic within LEOs. Excessive use of force by police officers has repeatedly been in the national spotlight, requiring immediate and effective solutions (Dewan & Oppell 2015; Rajaratnam et al. 2011; Violanti et al. 2014). MT is postulated to reduce aggression through mechanisms such as exposure to unpleasant experiences, cognitive change, and enhanced self-control, leading to effective and long-term behavioral change (Baer 2003; Fix & Fix 2013). Consistent with recent findings (Fix & Fix 2013; Christopher et al., 2018), our participants demonstrated significant reductions in self-reported aggression levels post-MT, reinforcing the potential of MT as an effective intervention to target aggression. Literature exploring the amount of and specific meditation practices to achieve benefits regarding aggression reduction, however, remains limited.

In one of the few studies reporting adherence levels in number of days of practice, a clinical sample of individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder reported mental health benefits after receiving MBCT, and reported engagement in practice of 47% of the possible days (Perich, Manicavasagar, Mitchell, Ball, & Hadzi-Pavlovic 2013). Our results, on the other hand, showed that participants’ engagement reflected an average of about 25% (14.44 out of 56) of the possible days. In comparison, adherence levels in our study would be considered low, but the totality of days engaged in practice was significantly correlated to reductions in aggression, suggesting that even limited and non-regular practice may impact aggression among LEOs. Age, job rank and years in the force were not correlated to overall days engaged in practice, indicating that these factors were not likely facilitators or were barriers to practice.

Overall, our findings demonstrated the differential impact of specific practices among LEOs. These results reinforce the idea that particular practices may be more effective among specific populations. Our findings also demonstrated that the collective amount of specific practices, and not the regularity of practice, had a greater impact on aggression. This particular result suggests that the cumulative effect of mild to high amounts of mindfulness practices in a short period of time may be more relevant than the steady frequency of low amounts per week. Such findings can have great implications towards the current MBP formats with respect to duration of protocols and amount of home practice suggested. Our findings support a lower adherence requirement and a shorter protocols, like the MBP immersion models, for example, in contrast to the standard 8-week programs. More studies, however, are needed to further explore adherence levels using objective measures, so that more in-depth considerations are made regarding the potential differences between frequency and duration of practices in relation to outcomes.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study aimed to contribute to the “what works for whom” discussion in the mindfulness literature, exploring the impact of frequency and duration of specific types of practice on aggression among LEOs. We acknowledge that due to its exploratory nature, results should be interpreted with caution. The scarcity of published materials targeting the specifics of adherence to practice provided limited support for the development of a more objective design for tracking adherence in this study. Although we used an objective tracking device, the iMINDr is only able to record the frequency and duration of played meditations tracks. The sustained engagement or the quality of practice, however, is not measurable without complex physiological devices. Therefore, it is possible that our findings are not fully reflective of quality of practice (e.g., daydreaming, dozing), potentially offering misleading results. The quality of practice may impact outcomes more than simple frequency or duration. Also, baseline mental health status (e.g. previous traumatic experiences, personality traits) may have influenced adherence levels and quality engagement to practice, potentially affecting results. More studies using an active control sample my reveal impacting co-variates (Oken 2008). Additional limitations, such as the small sample size and the ethnically and geographically homogenous sample, also need to be considered when interpreting results. Further studies, with larger and more diverse samples, and with measures assessing quality of practice, should continue to explore the relationship between mindfulness practice and outcomes in high-stress groups, including LEOs.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thanks to all the participants who dedicated their time and energy to participating in the study.

Funding and conflict of interest.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Complementary & Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R21AT008854. Leticia Ribeiro, M.S. has a PhD grant funded by the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq/SWB) award number 210325/2014-3. She also received funding from the Mind & Life Institute to attend and speak at the International Symposium for Contemplative Research 2018. Dana Colgan, PhD has her post-doc position and research supported by the NIH (T32 AT002688 and K24 AT005121). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development. All other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Ethical approval. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Pacific University Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Anālayo B (2011). Right View and the Scheme of the Four Truths in Early Buddhism– The Samyukta-āgama Parallel to the Sammāditthi-sutta and the Simile of the Four Skills of a Physician. Canadian Journal of Buddhist Studies, 7, 11–44. Retrieved from https://www.buddhismuskunde.uni-hamburg.de/pdf/5-personen/analayo/right-view.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Avdija AS (2014). Stress and law enforcers: Testing the relationship between law enforcement work stressors and health-related issues. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 100–110. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2013.878657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA (2009). Self-focused attention and mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based treatment. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38(S1), 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, … & Williams JMG (2008). Construct validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee M, Cavanagh K, & Strauss C (2017). A qualitative study with healthcare staff exploring the facilitators and barriers to engaging in a self-help mindfulness-based intervention. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1653–1664.doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0740-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergomi C, Tschacher W, & Kupper Z (2015). Meditation practice and self-reported mindfulness: a cross-sectional investigation of meditators and non-meditators using the Comprehensive Inventory of Mindfulness Experiences (CHIME). Mindfulness, 6(6), 1411–1421. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0415-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB, & Smith BD (2001). Refining the architecture of aggression: A measurement model for the Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 35(2), 138–167.doi: 10.1006/jrpe.2000.2302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, & Perry M (1992). The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 452.doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can SH, & Hendy HM (2014). Police stressors, negative outcomes associated with them and coping mechanisms that may reduce these associations. The Police Journal, 87(3), 167–177. doi: 10.1350/pojo.2014.87.3.676 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Tamagawa R, Stephen J, Drysdale E, Zhong L, & Speca M (2016). Randomized-controlled trial of mindfulness-based cancer recovery versus supportive expressive group therapy among distressed breast cancer survivors (MINDSET): Long-term follow-up results. Psycho-Oncology, 25(7), 750–759. doi: 10.1002/pon.4150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash E, Salmon P, Weissbecker I, Rebholz WN, Bayley-Veloso R, Zimmaro LA, … & Sephton SE (2014). Mindfulness meditation alleviates fibromyalgia symptoms in women: results of a randomized clinical trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49(3), 319–330. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9665-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, Calati R, & Serretti A (2011). Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities?: A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 449–464. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher MS, Christopher V, & Charoensuk S (2009). Assessing “western” mindfulness among Thai Theravāda Buddhist monks. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 12(3), 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher MS, Goerling RJ, Rogers BS, Hunsinger M, Baron G, Bergman AL, & Zava DT (2016). A pilot study evaluating the effectiveness of a mindfulness-based intervention on cortisol awakening response and health outcomes among law enforcement officers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 31(1), 15–28. doi: 10.1007/s11896-015-9161-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher MS, Hunsinger M, Goerling LRJ, Bowen S, Rogers BS, Gross CR, … & Pruessner JC (2018). Mindfulness-based resilience training to reduce health risk, stress reactivity, and aggression among law enforcement officers: A feasibility and preliminary efficacy trial. Psychiatry Research, 264, 104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan DD, Christopher M, Michael P, & Wahbeh H (2016). The Body Scan and Mindful Breathing among veterans with PTSD: Type of intervention moderates the relationship between changes in mindfulness and post-treatment depression. Mindfulness, 7(2), 372–383. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan DD, Wahbeh H, Pleet M, Besler K, & Christopher M (2017). A qualitative study of mindfulness among veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Practices differentially affect symptoms, aspects of well-being, and potential mechanisms of action. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 22(3), 482–493. doi: 10.1177/2156587216684999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JD, & Lindsay EK (2014). How does mindfulness training affect health?:A mindfulness stress buffering account. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(6), 401–407. doi:1177/0963721414547415 [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, & Kaszniak AW (2015). Conceptual and methodological issues in research on mindfulness and meditation. American Psychologist, 70(7), 581.doi: 10.1037/a0039512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewan S, & Oppel RA Jr. (2015). In Tamir Rice case, many errors by Cleveland police, then a fatal one. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/23/us/in-tamir-rice-shooting-in-cleveland-many-errors-by-police-then-a-fatal-one.html [Google Scholar]

- De Vibe M, Bjørndal A, Tipton E, Hammerstrøm K, & Kowalski K (2012). Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) for improving health, quality of life, and social functioning in adults. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 8(1), 1–127. doi: 10.4073/csr.2012.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dreeben SJ, Mamberg MH, & Salmon P (2013). The MBSR body scan in clinical practice. Mindfulness, 4(4), 394–401. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0212-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin PL, & Zhao Q (2011). Increased mindfulness -The active component of the mindfulness-based stress reduction program? Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 17(1), 22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Bermudez D, Matas A, Majid H, & Myers NL (2013). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for low-income, predominantly African American women with PTSD and a history of intimate partner violence. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(1), 23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman G, Greeson J, & Senville J (2010). Differential effects of mindful breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and loving-kindness meditation on decentering and negative reactions to repetitive thoughts. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(10), 1002–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fix RL, & Fix ST (2013). The effects of mindfulness-based treatments for aggression: A critical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(2), 219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.11.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon RR, Barocas B, Canton AN, Li X, & Vlahov D (2009). Mental, physical, and behavioral outcomes associated with perceived work stress in police officers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(3), 275–289. doi: 10.1177/0093854808330015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin SP, & Bernard TJ (2003). Angry aggression among police officers. Police Quarterly, 6(1), 3–21.doi: 10.1177/1098611102250365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross CR, Kreitzer MJ, Reilly-Spong M, Wall M, Winbush NY, Patterson R, … & Cramer-Bornemann M (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction versus pharmacotherapy for chronic primary insomnia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing, 7(2), 76–87. 10.1016/j.explore.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, & Cavanagh K (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KE, Kesmodel US, Kold M, & Forman A (2017). Long-term effects of mindfulness-based psychological intervention for coping with pain in endometriosis: a six-year follow-up on a pilot study. Nordic Psychology, 69(2), 100–109. doi: 10.1080/19012276.2016.1181562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge EA, Guidos BM, Mete M, Bui E, Pollack MH, Simon NM, & Dutton MA (2017). Effects of mindfulness meditation on occupational functioning and health care utilization in individuals with anxiety. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 95, 7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Vangel M, Congleton C, Yerramsetti SM, Gard T, & Lazar SW (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 191(1), 36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, & Ott U (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AP, Krompinger J, & Baime MJ (2007). Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(2), 109–119. doi: 10.3758/cabn.7.2.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AP, Morrison AB, Parker SC, & Stanley EA (2017). Practice is protective: Mindfulness training promotes cognitive resilience in high-stress cohorts. Mindfulness, 8(1), 46–58. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0465-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (1990). Full catastrophe living: The program of the stress reduction clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. New York, NY: Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, & Burney R (1985). The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 8(2), 163–190. doi: 10.1007/bf00845519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AP, Erickson TM, Giardino ND, Favorite T, Rauch SA, Robinson E, … & Liberzon I (2013). A pilot study of group mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Depression and Anxiety, 30(7), 638–645. 10.1002/da.22104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury B, Sharma M, Rush SE, & Fournier C (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kop N, Euwema M, & Schaufeli W (1999). Burnout, job stress and violent behaviour among Dutch police officers. Work & Stress, 13(4), 326–340. doi: 10.1080/02678379950019789 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz DL, Zavala E, & Melander LA (2015). The influence of early strain on later strain, stress responses, and aggression by police officers. Criminal Justice Review, 40(2), 190–208. doi: 10.1177/0734016814564696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay EK, & Creswell JD (2017). Mechanisms of mindfulness training: Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd A, White R, Eames C, & Crane R (2017). The utility of home-practice in mindfulness-based group interventions: a systematic review. Mindfulness, 9(3), 673–692. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0813-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz A, Jha AP, Dunne JD, & Saron CD (2015). Investigating the phenomenological matrix of mindfulness-related practices from a neurocognitive perspective. American Psychologist, 70(7), 632. doi: 10.1037/a0039585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez ME, Kearney DJ, Simpson T, Felleman BI, Bernardi N, & Sayre G (2015). Challenges to enrollment and participation in mindfulness-based stress reduction among veterans: A qualitative study. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(7), 409–421. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Depp CA, Wetherell JL, & Lenze EJ (2016). Ecological momentary assessment versus standard assessment instruments for measuring mindfulness, depressed mood, and anxiety among older adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 75, 116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys A, Savelsbergh GJ, & Oudejans RR (2012). Shoot or don’t shoot? Why police officers are more inclined to shoot when they are anxious. Emotion, 12(4), 827. doi: 10.1037/a0025699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara AF, Violanti JM, Levenson RL Jr, & Clark RG Sr (2013). National police suicide estimates: Web surveillance study III. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience Retrieved from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-42910-004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oken BS (2008). Placebo effects: clinical aspects and neurobiology. Brain, 131(11), 2812–2823. 10.1093/brain/awn116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons CE, Crane C, Parsons LJ, Fjorback LO, & Kuyken W (2017). Home practice in Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of participants’ mindfulness practice and its association with outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 95, 29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perich T, Manicavasagar V, Mitchell PB, Ball JR, & Hadzi-Pavlovic D (2013). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 127(5), 333–343.doi: 10.1111/acps.12033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quach D, Gibler RC, & Mano KEJ (2017). Does home practice compliance make a difference in the effectiveness of mindfulness interventions for adolescents?. Mindfulness, 8(2), 495–504.doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0624-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaratnam SM, Barger LK, Lockley SW, Shea SA, Wang W, Landrigan CP, … & Epstein LJ (2011). Sleep disorders, health, and safety in police officers. Jama, 306(23), 2567–2578. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro L, Atchley RM, & Oken BS (2018). Adherence to practice of mindfulness in novice meditators: practices chosen, amount of time practiced, and long-term effects following a mindfulness-based intervention. Mindfulness, 9(2), 401–411.doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0781-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffault A, Czernichow S, Hagger MS, Ferrand M, Erichot N, Carette C, … & Flahault C (2017). The effects of mindfulness training on weight-loss and health-related behaviours in adults with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 11(5), 90–111. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JM, Teasdale JD, & Gemar M (1996). A cognitive science perspective on kindling and episode sensitization in recurrent affective disorder. Psychological Medicine, 26(2), 371–380.doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams M, & Teasdale J (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York, NY:Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vettese L;Toneatto T, Stea JN, Nguyen L, & Wang JJ Do mindfulness meditation participants do their homework? And does it make a difference?: A review of the empirical evidence. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(3), 198–225. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.23.3.198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Violanti JM, Andrew ME, Burchfiel CM, Dorn J, Hartley T, & Miller DB (2006). Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease in police officers. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(4), 541. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Violanti JM, Slaven JE, Charles LE, Burchfiel CM, Andrew ME, & Homish GG (2011). Police and alcohol use: A descriptive analysis and associations with stress outcomes. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 36(4), 344–356. doi: 10.1007/s12103-011-9121-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Violanti J, Mnatskanova A, Michael A, Tara H, Desta F, Penelope B, & Cecil B (2014). 0037 Associations of stress, anxiety, and resiliency in police work. Occupational Environmental Medicine, 71(Suppl 1), A3–A3. Retrieved from: https://oem.bmj.com/content/71/Suppl_1/A3.2 [Google Scholar]

- Visted E, Vøllestad J, Nielsen MB, & Nielsen GH (2015). The impact of group-based mindfulness training on self-reported mindfulness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 6(3), 501–522. doi: 10.1007/s12671-014-0283-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wahbeh H, Zwickey H, & Oken B (2011). One method for objective adherence measurement in mind–body medicine. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 17(2), 175–177. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]