Abstract

Law enforcement personnel (LEPs) experience occupational stressors that can result in poor health outcomes and have a negative impact on the communities they serve. Dispositional mindfulness, or receptive awareness and attention to present moment experience, has been shown to negatively predict perceived stress and to moderate the relationship between stressors and negative stress-related outcomes. The current study is an investigation of the moderating role of specific facets of dispositional mindfulness (i.e., nonreactivity, nonjudging, and acting with awareness) in the relationship between occupational stressors and perceived stress in a sample of LEPs. As hypothesized, nonreactivity significantly moderated the relationship between operational stressors and perceived stress, such that LEPs low in nonreactivity exhibited a significant relationship between stressors and perceived stress, whereas those high in nonreactivity did not. Nonjudging also moderated the relationship between organizational stressors and perceived stress; however, unexpectedly, LEPs high in nonjudging evidenced a significant relationship between stressors and perceived stress, whereas those low in nonjudging did not. Potential implications of these findings for LEP stress reduction interventions are discussed.

Keywords: mindfulness, police, perceived stress

Law enforcement personnel (LEPs) are exposed to significant and continuous stressors, and experience higher rates of depression (Wang et al., 2010), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Marmar et al., 2006), alcohol use disorders (Rees & Smith, 2008), and suicide (Clark, White, & Violanti, 2012), relative to the general population. Common categories of LEP-specific stressors are operational and organizational (McCraty & Atkinson, 2012; Tuckey, Winwood, & Dollard, 2012). Operational stressors include high-speed chases, physical threat, shift work, and negative interactions with the public (McCraty & Atkinson, 2012), whereas organizational stressors include internal politics, inequality of opportunity, lack of resources, overtime, and staff shortages (Tuckey et al., 2012). Among LEPs, occupational stressors have been linked to increased aggression (Ma et al., 2015), anger (Rajaratnam et al., 2011), and burnout (Wirth et al., 2013). Effects of stress in LEPs can also lead to public harm; stress-impaired LEPs are at greater risk for poor job-related outcomes, such as administrative and tactical errors (Rajaratnam et al., 2011), and stress-influenced poor decision-making is often implicated as a primary factor in excessive use of force (Nieuwenhuys, Savelsbergh, & Oudejans, 2012).

The relationship between stressors and perceived stress is unclear, which may indicate the presence of moderating factors. For example, while several studies have found that occupational stressors predict perceived stress among LEPs (e.g., Walvekar et al., 2015) and in the general public (e.g., Gartland, O’Connor, Lawton, & Bristow, 2014), other studies have found weak or no relationships between stressors and stress (e.g., Vasunilashorn et al., 2014). Other studies assessing possible moderating factors have found that trait-like characteristics, such as resilience, moderate the relationship between stressors and perceived stress (e.g., Dale et al., 2015). One such trait is dispositional mindfulness, which is an individual’s receptive awareness and attention to present moment experience (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Dispositional mindfulness negatively predicts perceived stress (Zimmaro et al., 2016) and moderates the relationship between stressors and several outcomes, including rumination (Ciesla, Reilly, Dickson, Emanuel, & Updegraff, 2012), depression, anxiety, and stress (Marks, Sobanski, & Hine, 2010).

While research on the relationship between mindfulness and LEP outcomes is limited, mindful acceptance negatively predicts depression among LEPs in training (Williams et al., 2010) and PTSD symptoms among active-duty LEPs (Chopko & Schwartz, 2013), and mindfulness training reduces occupational stressors and anger among LEPs (Bergman, Christopher, & Bowen, 2016). The goal of the current study was to extend this body of literature, and to examine whether facets of dispositional mindfulness (acting with awareness, nonreactivity, and nonjudging) moderate the impact of occupation-specific stressors on perceived stress among LEPs.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from a police department in a medium-sized city in the Pacific Northwestern U.S. from Spring 2013 to Spring 2014. Eligible department personnel were invited to participate in an 8-week Mindfulness-Based Resilience Training course (see Christopher et al., 2016 for details). In this secondary analysis, we used the baseline data of 72 participants: 48 officers, 10 civilian support staff, 9 sergeants, 3 lieutenants, and 2 other. The sample was 57% male, and the average age was 43.53 years (SD = 7.72; range = 24–61). Approximately 81% identified as Euro-American; 13% as Latino/a American; and 6% as Other. The average number of years on duty was 13.28 (SD = 5.94; range 2–25).

Self-Report Measures

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form (FFMQ-SF; Bohlmeijer et al., 2011), a 24-item version of the FFMQ (Baer et al., 2006), was used to assess the dispositional tendency to be mindful in daily life. In the current study, we only included the acting with awareness (AA), nonjudging of inner experience (NJ), and nonreactivity to inner experience (NR) facets. Each of these facets had five items, resulting in a 15-item scale. Internal consistency of each facet in the present sample was good (AA α = 0.79; NJ α = 0.84; NR α = 0.84).

The Police Stress Questionnaire (PSQ; McCreary & Thompson, 2006) is a 40-item questionnaire consisting of two subscales measuring operational stressors (20 items) and organizational stressors (20 items). The subscales have demonstrated excellent factorial validity and expected convergent validity (Shane, 2010). In our sample, both operational (α = .85) and organizational (α = .88) factors demonstrated good internal consistency.

The 4-item Perceived Stress Scale-4 (PSS-4; Cohen & Williamson, 1988) was used to assess the degree to which life situations are perceived as stressful, with items measuring how overwhelming respondents perceive their lives to be. The PSS-4 has demonstrated expected correlations with a variety of constructs (Cohen & Williamson, 1988), and in the present sample demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (α = .69).

Design and Analyses

To test our hypothesized moderations, PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2012) for SPSS-23 (SPSS Inc., 2013) was used. The interaction between each independent variable (operational and organizational stressors) and moderator variable (NR, NJ, and AA) was examined for the dependent variable (perceived stress), for a total of 6 regression analyses. For each model, either organizational (3 models) or operational stressors (3 models) were entered in Step 1; one of the three FFMQ subscales (NR, NJ, and AA) was entered in Step 2; and the interaction between these two variables was entered in Step 3. A p value of .05 was retained for significance, despite multiple analytic tests, due to the small sample size, exploratory nature, and novel population of the study.

Results

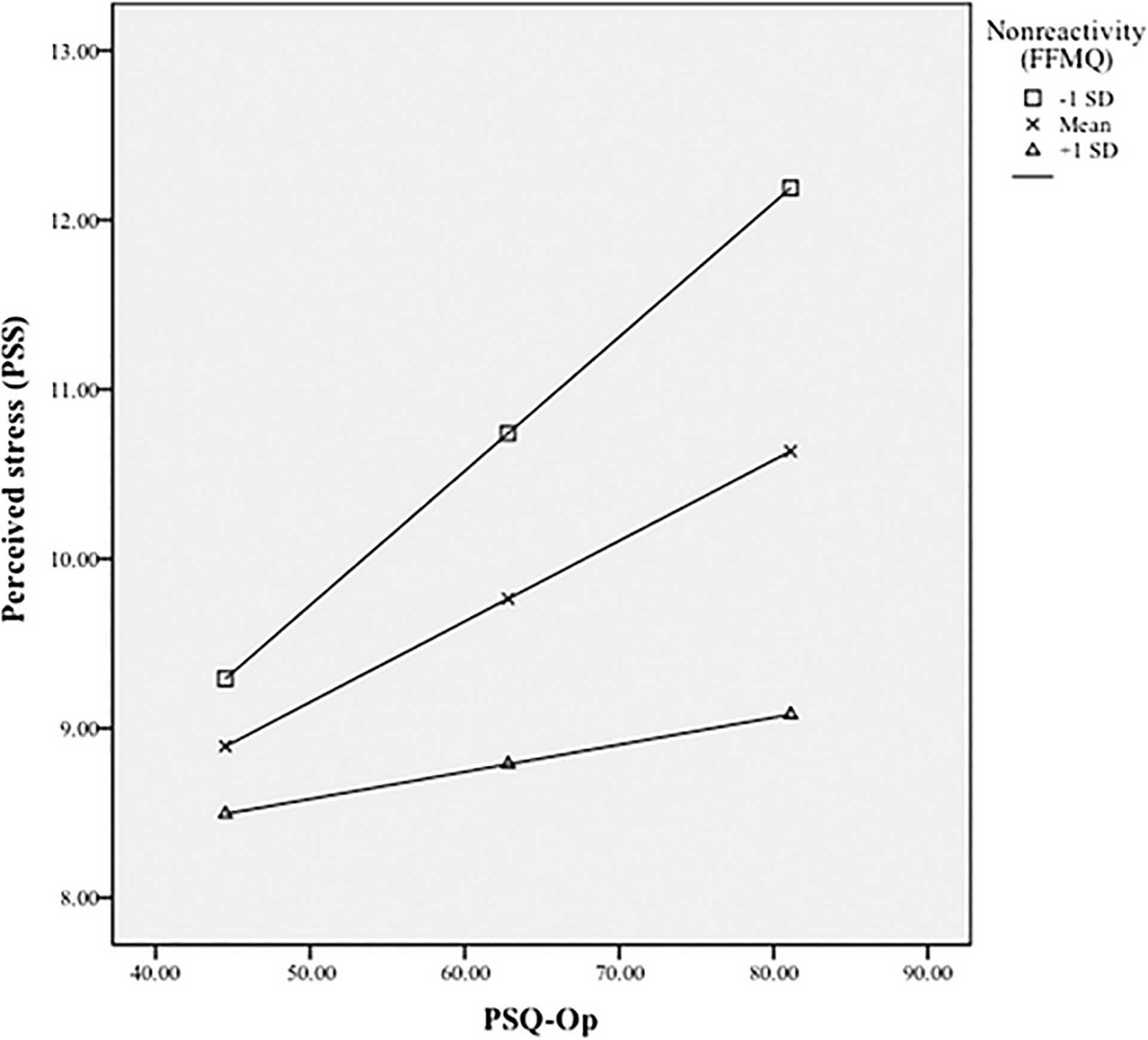

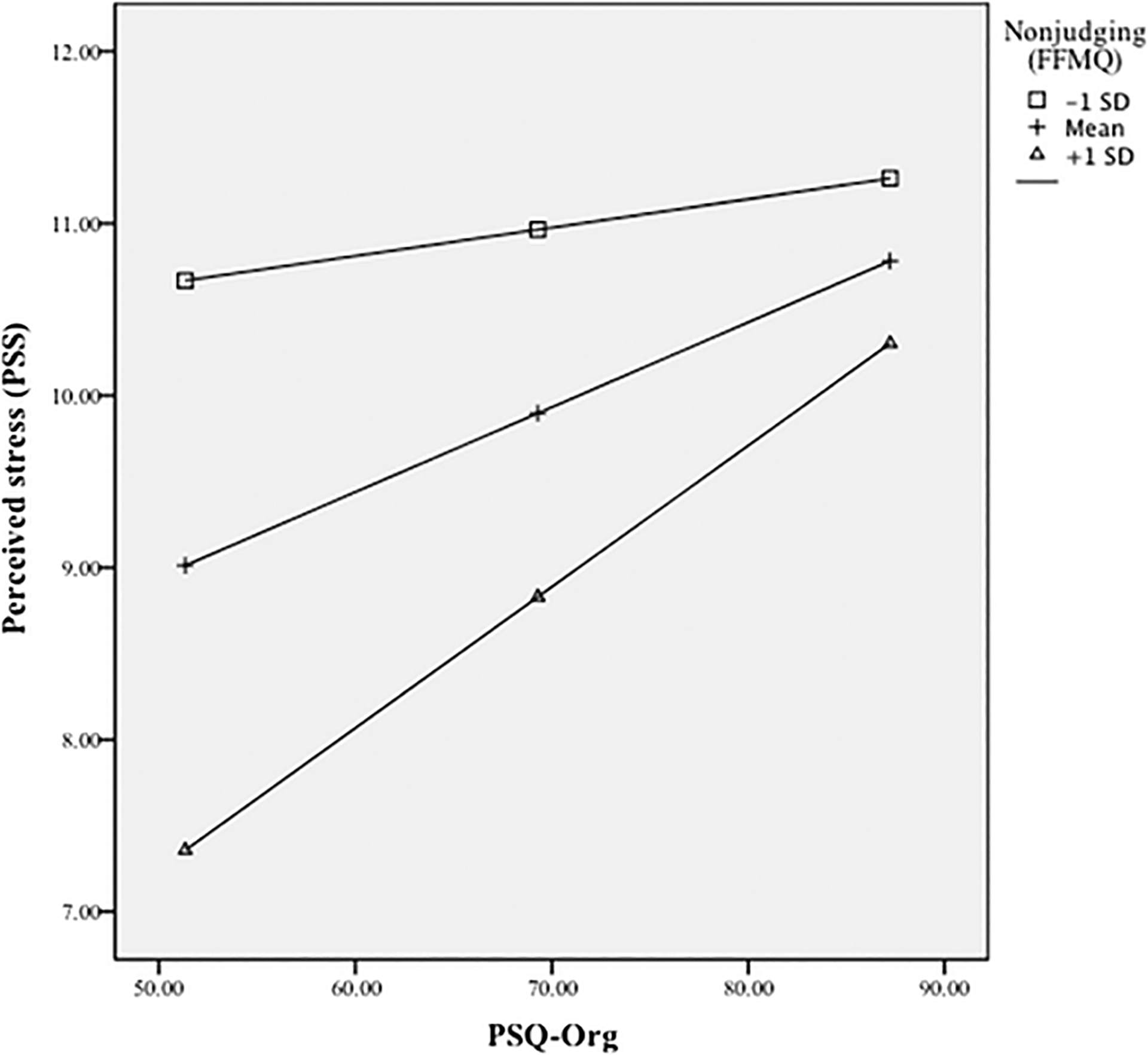

All variables were normally distributed and there were no univariate outliers; however, two multivariate outlier cases were excluded. Correlations between all study variables as well as Means and Standard Deviations may be found in Table 1. Our results included two significant main effects for facets of mindfulness predicting perceived stress in this sample (see Table 2). AA (p = .02) and NJ (p = .004) significantly predicted perceived stress above organizational stressors. Two of the six interactions tested were significant (see Table 2): First, NR moderated the relationship between operational stressors and perceived stress (p = .01). As predicted, simple slope analyses revealed that when NR was high (+1 SD), the relationship between operational stressors and perceived stress was non-significant, whereas this relationship was statistically significant at average (Mean; p = .004) and low (−1 SD; p < .001) levels of NR (see Figure 1). Second, NJ moderated the relationship between organizational stressors and perceived stress (p = .04). Unexpectedly, simple slope analyses revealed that when NJ was low (−1 SD), the relationship between organizational stressors and perceived stress was non-significant, whereas it was significant at average (Mean; p = .003) and high (+1 SD; p < .001) levels of NJ. Although the simple slope analysis revealed that organizational stressors predicted perceived stress at only average and high levels of NJ, those who were low in NJ endorsed higher levels of perceived stress at all levels of organizational stressors (see Figure 2).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for study variables

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Nonreactivity | 14.40 | 2.97 | --- | ||||

| 2. Nonjudging | 16.94 | 3.66 | .41*** | --- | |||

| 3. Act with Awareness | 14.36 | 3.29 | .12 | .26* | --- | ||

| 4. PSQ-Org | 69.29 | 17.94 | −.14 | −.17 | −.22 | --- | |

| 5. PSQ-Op | 62.81 | 18.29 | −.06 | −.17 | −.13 | .50*** | --- |

| 6. PSS | 9.80 | 2.78 | −.31** | −.46*** | −.48*** | .36** | .36** |

Note: Nonreactivity = Nonreactivity facet of Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, Nonjudging = Nonjudging facet of Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, Act with awareness = Act with awareness facet of Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, PSQ Org = Police Stress Questionnaire: Organizational subscale, PSQ Op = Police Stress Questionnaire: Operational subscale, PSS = Perceived Stress Scale

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .01

Table 2.

Results of regression models testing interactions between facets of dispositional mindfulness and police stressors on perceived stress

| Perceived stress | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | β | SE | B | p | ||

| Model 1 | .32 | <.001 | ||||

| PSQ Org | −.26 | .06 | −.04 | .53 | ||

| AWA | −.88 | .30 | −.74 | .02 | ||

| PSQ Org × AWA | .63 | .01 | .01 | .18 | ||

| Model 2 | .34 | <.001 | ||||

| PSQ Org | −.66 | .07 | −.10 | .170 | ||

| NJ | −1.20 | .30 | −.91 | .004 | ||

| PSQ Org × NJ | 1.15 | .01 | .01 | .04 | ||

| Model 3 | .20 | .002 | ||||

| PSQ Org | .25 | .07 | .04 | .60 | ||

| NR | −.33 | .35 | −.31 | .38 | ||

| PSQ Org × NR | .10 | .01 | .001 | .86 | ||

| Model 4 | .32 | <.001 | ||||

| PSQ Op | .43 | .07 | .07 | .33 | ||

| AWA | −.35 | .27 | −.30 | .27 | ||

| PSQ Op × AWA | −.15 | .01 | −.01 | .76 | ||

| Model 5 | .30 | <.001 | ||||

| PSQ Op | .68 | .08 | .10 | .20 | ||

| NJ | −.16 | .27 | −.12 | .66 | ||

| PSQ Op × NJ | −.43 | .01 | −.01 | .45 | ||

| Model 6 | .28 | <.001 | ||||

| PSQ Op | 1.32 | .06 | .20 | .002 | ||

| NR | .36 | .26 | .34 | .20 | ||

| PSQ Op × NR | −1.18 | .01 | −.01 | .01 | ||

Note: All values presented at regression Step 3. PSQ Org = Police Stress Questionnaire: Organizational subscale, PSQ Op = Police Stress Questionnaire: Operational subscale, AWA = Act with awareness facet of Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, NJ = Nonjudging facet of Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, NR = Nonreactivity facet of Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire

Figure 1. Simple Slopes of Operational Stress (PSQ-Op) in the prediction of Perceived Stress (PSS) at low (−1 SD), medium (Mean), and high (+1 SD) values of Nonreactivity.

Note: PSS = Perceived Stress Scale, PSQ-OP = Police Stress Questionnaire: Operational subscale, FFMQ = Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire

Figure 2. Simple Slopes of Organizational Stress (PSQ-Org) in the prediction of Perceived Stress (PSS) at low (−1 SD), medium (Mean), and high (+1 SD) values of Nonjudging.

Note: PSS = Perceived Stress Scale, PSQ-Org = Police Stress Questionnaire: Organizational subscale, FFMQ = Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire

Given that the relationship between police stressors and perceived stress was non-significant when NJ was low (−1 SD) and when NR was high (+1 SD), we tested a post-hoc interaction model between these facets in predicting perceived stress. Both facets negatively predicted perceived stress (NJ [β = −.46, p < .001] and NR [β = −.31, p = .008]), and the interaction between NJ and NR (in step 2) also predicted perceived stress (β = 1.72, p = .013). Simple slopes for each combination of the moderation revealed that when either NR or NJ were low (−1 SD), the relationship between the other facet and perceived stress was significant. However, when either NR or NJ were high (+1 SD), the relationship between the other facet and perceived stress was not significant.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine whether facets of dispositional mindfulness (acting with awareness, nonreactivity, and nonjudging) buffer the impact of police stressors on perceived stress among LEPs. Results revealed that both NJ and NR were significant moderators of this relationship. As expected, at low levels of NR (−1 SD), the relationship between operational stressors and perceived stress was significant, but not at high levels of NR (+1 SD), suggesting that higher nonreactivity in LEPs may buffer effects of stressors on their perceived stress. This is consistent with research that has shown occupational stressors experienced by LEPs are related to perceived stress (Inslicht et al., 2011; Walvekar et al., 2015; Wirth et al., 2013), and that dispositional traits, such as resilience, moderate this relationship (Dale et al., 2015).

In a second model, NJ moderated the relationship between organizational stressors and perceived stress; however, unexpectedly, the relationship was statistically significant at average (Mean) and high levels (+1 SD) of NJ, and not low levels. Closer inspection of the simple slope analysis revealed that those who were low in NJ (i.e., a higher tendency to negatively evaluate or judge inner experience) endorsed higher levels of perceived stress at all levels of organizational stress, whereas those who were high in NJ endorsed much lower levels of perceived stress when organizational stress was low. This finding suggests that NJ may confer protective benefits at lower levels of stressors, while its benefit may not be enough to mitigate the impact of higher levels of stressors. This interaction may also be partially explained by the nature of LEP training and experience, in which rapid decision and judgment is an essential occupational skill (Storey, Gibas, Reeves, & Hart 2011), and perhaps in periods of higher stressors, quick judgment of internal experiences, even when negative, may help buffer against perceived stress.

In a post-hoc analysis, we found that NJ and NR interacted to confer additional protective benefit against stress. Specifically, low levels of both NJ and NR, reflecting tendencies to judge and react to internal experience, were related to higher levels of perceived stress. Baer (2006) suggested that collectively NJ and NR may be represent acceptance, and ease of working with internal experience. Other research has substantiated the importance of this interaction; mindfulness training studies have shown that pre-post training improvements in NR and NJ inversely predict depression symptoms in veterans (Colgan, Christopher, Michael, & Wahbeh, 2016), and aggression and anger among police (Bergman et al., 2016). Relatedly, NJ and AA have demonstrated synergistic effects in predicting impulsivity and anger (Peters, Eisenlohr-Moul, Upton, & Baer, 2013).

This study has several limitations. The small sample size limited power, and thus our ability to detect significant interactions and the generalizability of the findings. Several measures also had acceptable, but not excellent internal consistency. Several covariates that may have influenced the relationship between stressors and stress, such as time of employment, were not included in the regression models. Finally, cross-sectional data also limits the generalizability of the current findings. For these reasons, our findings require replication with a larger sample size and more thorough control of variables in order to maximize generalizability. Additionally, the potential limitations of measurement by self-report include response bias, practice effects, and regression toward the mean. These pitfalls are exacerbated by the challenge of measuring the construct of mindfulness. For example, the FFMQ shows inconsistent psychometric properties among meditations and non-meditators (de Bruin et al., 2012) and has been critiqued for poor cultural validity and insufficient construct content by recognized mindfulness experts (Christopher, Woodrich, & Tiernan, 2014). In order to address these shortcomings, future research should incorporate more objective, physiological measures of mindfulness. Despite these limitations, this study suggests that facets of dispositional mindfulness may confer protective benefits against the impact of occupational stressors among LEPs. While these promising findings need further study, they offer an exciting possibility for improving first responder health, and subsequently improving the well-being of the communities they serve.

Biographical Sketch:

Josh Kaplan received his M.S. in Clinical Psychology from Pacific University. He is currently a student in Pacific University’s Clinical Psychology Ph.D. program. His research interests include resilience and mindfulness in high-risk occupations, as well as the measurement of both psychological and physiological resilience.

Michael S. Christopher received his Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology from The University of South Dakota. He is an associate professor in the Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology Program at Pacific University. His research interests include mindfulness and acceptance-based approaches to enhance resilience in high-risk occupations and mindfulness assessment and practice across cultural contexts.

Sarah Bowen received her Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology from The University of Washington. She is an assistant professor in the Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology Program at Pacific University. Her research interests include treatment of addictive behaviors and prevention of relapse, dual diagnosis populations, incarcerated adults and adolescents, mindfulness-based approaches to treating addiction and impulsive behavior.

References

- Anshel MH, & Brinthaupt TM (2014). An exploratory study on the effect of an approach-avoidance coping program on perceived stress and physical energy among police officers. Psychology 5(7):676–687. doi: 10.4236/psych.2014.57079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan C (2010). An investigation of anger and anger expression in terms of coping with stress and interpersonal problem-solving. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice 10(1):25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, & Toney L (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 13(1):27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj B, & Pande N (2016). Mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 93: 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bao X, Xue S, & Kong F (2015). Dispositional mindfulness and perceived stress: The role of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences 78: 1116–1119 [Google Scholar]

- Bergman AL, Christopher MS, & Bowen S (2016). Changes in facets of mindfulness predict stress and anger outcomes for police officers. Mindfulness. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer E, Peter M, Fledderus M, Veehof M, & Baer R (2011). Psychometric properties of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Assessment: 308–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, & Ryan RM (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84(4):822–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher MS, Goerling RJ, Rogers BS, Hunsinger MH, Baron G, Bergman A, & Zava DT (2016). A pilot study of evaluating the effectiveness of a mindfulness-based intervention on cortisol awakening response and health outcomes among law enforcement officers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 31, 15–28 doi: 10.1007/s11896-015-9161-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher MS, Woodrich LE, & Tiernan KA (2014). Using cognitive interviews to assess the cultural validity of state and trait measures of mindfulness among Zen Buddhists. Mindfulness 5:145–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopko BA, & Schwartz RC (2013). The relation between mindfulness and posttraumatic stress symptoms among police officers. Journal of Loss and Trauma 18(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Reilly LC, Dickson KS, Emanuel AS, & Updegraff JA (2012). Dispositional mindfulness moderates the effects of stress among adolescents: Rumination as a mediator. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 41(6):760–770. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.698724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan D, Christopher M, Michael P, & Wahbeh H (2016). The body scan and mindful breathing among veterans with PTSD: Type of intervention moderates the relationship between changes in mindfulness and post-traumatic depression. Mindfulness 7: 372–383. 10.1007/s12671-015-0453-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin EI, Topper M, Muskens JG, Bögels SM, & Kamphuis JH (2012) Psychometric properties of the Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) in a meditating and a non-meditating sample. Assessment 19(2):187–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, & Kemeny ME, (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol. Bull 130(3):35–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves-Lord K, Ferdinand RF, Oldehinkel AJ, Sondeijker FE, Ormel J, & Verhulst FC (2007). Higher cortisol awakening response in young adolescents with persistent anxiety problems. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 116(2): 137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01001.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

- Hirvikoski T, Lindholm T, Nordenstrom A, Nordstrom A, & Lajic S (2009). High self-perceived stress and many stressors, but normal diurnal cortisol rhythm, in adults with ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder). Hormones and Behavior 55(3):418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Inslicht SS, Otte C, McCaslin SE, Apfel BA, Henn-Haase C, Metzler T, Yehuda R, Neylan TC, & Marmar CR (2011). Cortisol awakening response prospectively predicts peritraumatic and acute stress reactions in police officers. Biological Psychiatry 70(11): 1055–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan J, Bergman A, Hunsinger M, Bowen S, & Christopher M (2016). Resilience mediates the relationship between mindfulness training and burnout among first responders. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Kligyte V, Connelly S, Thiel C, & Devenport L (2013). The influence of anger, fear, and emotion regulation on ethical decision making. Human Performance, 26(4):297–326. doi: 10.1080/08959285.2013.814655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma CC, Andrew ME, Fekedulegn D, Gu JK, Hartley TA, Charles LE, Violanti J,&N, Burchfiel CM (2015). Shift work and occupational stress in police officers. Safety and Health at Work 6(1):25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks AD, Sobanski DJ, & Hine DW (2010). Do dispositional rumination and/or mindfulness moderate the relationship between life hassles and psychological dysfunction in adolescents. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 44(9): 831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmar CR, McCaslin SE, Metzler TJ, Best S, Weiss DS,…& Neylan T (2006). Predictors of posttraumatic stress in police and other first responders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1071(1):1–18. 10.1196/annals.1364.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCraty R, & Atkinson M (2012). Resilience training program reduces physiological and psychological stress in police officers. Global Advances in Health and Medicine 1(5):42–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary DR, & Thompson MM (2006). Development of two reliable and valid measures of stressors in policing: The operational and organizational police stress questionnaires. International Journal of Stress Management 13(4):494. [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, & Chen E (2006). Life stress and diminished expression of genes encoding the glucocorticoid receptor and b2-adrenergic receptor in children with asthma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103(14):5496–5501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitzan-Assayag Y, Aderka IM, & Bernstein A (2015). Dispositional mindfulness in trauma recovery: Prospective relations and mediating mechanisms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 36: 25–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Upton BT, & Baer RA (2013). Nonjudgment as a moderator of the relationship between present-centered awareness and borderline features: Synergistic interactions in mindfulness assessment. Personality and Individual Differences 55: 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaratnam SW, Brager LK, Lockley SW, Shea SA, Wang W, Landrigan CP, & Czeisler CA (2011). Sleep disorders, health and safety in police officers. Journal of the American Medical Association 306(23):2567–2578. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees B, & Smith J (2008). Breaking the silence: The traumatic circle of policing. International Journal of Police Science & Management 10(2):267–279. doi: 10.1350/ijps.2008.10.3.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds K, & Miles HL (2009). The effect of training on the quality of HCR-20 violence risk assessments in forensic secure services. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 20, 473–480. [Google Scholar]

- Seip EC, Van Dijk WW, & Rotteveel M (2014). Anger motivates costly punishment of unfair behavior. Motivation and Emotion 38(4):578–588. doi: 10.1007/s11031-014-9395-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JE, Gibas AL, Reeves KA, & Hart SD (2011). Evaluation of a violence risk (threat) assessment training program for police and other criminal justice professionals. Criminal Justice and Behavior 38(6): 554–564. doi: 10.1177/0093854811403123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker RP, O’Keefe VM, Cole AB, Rhoades-Kerswill S, Hollingsworth DW, Helle AC, DeShong HL, Mullins-Sweatt SN, & Wingate LR (2014). Mindfulness tempers the impact of personality on suicidal ideation. Personality and Individual Differences 68:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckey MR, Winwood PC, & Dollard MF (2012). Psychosocial culture and pathways to psychological injuries within policing. Police Practice and Research 13(3):224–240. 10.1080/15614263.2011.574072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Son J, Nyklíček I, Nefs G, Speight J, Pop VJ, & Pouwer F (2014). The association between mindfulness and emotional distress in adults with diabetes: Could mindfulness serve as a buffer? Results from diabetes MILES: The Netherlands. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 38(2): 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasunilashorn S, Lynch SM, Glei DA, Weinstein M, & Goldman N (2014). Exposure to stressors and trajectories of perceived stress among older adults. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 70(2): 329–337. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Inslicht SS, Metzler TJ, Henn-Haase C, McCaslin SE, … & Marmar CR (2010). A prospective study of predictors of depressive symptoms in police. Psychiatry Research 175(3):211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams V, Ciarrochi J, & Deane FP (2010). On being mindful, emotionally aware, and more resilient: Longitudinal pilot study of police stress. Australian Psychologist 45(4):274–282. doi: 10.1080/00050060903573197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth M, Burch J, Violanti J, Burchfiel C, Fekedulegn D, Andrew M, Zhang H, Miller DB, Hebert JR, & Vena JE (2013). Shiftwork duration and the awakening cortisol response among police officers. Chronobiology International 28(5): 446–457. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.573112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie D (2011). Implementing a Tactical Fitness Program. Police One.Com News [Google Scholar]