Abstract

PURPOSE

To develop guideline recommendations concerning optimal neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer.

METHODS

ASCO convened an Expert Panel to conduct a systematic review of the literature on neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer and provide recommended care options.

RESULTS

A total of 41 articles met eligibility criteria and form the evidentiary basis for the guideline recommendations.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy should be managed by a multidisciplinary care team. Appropriate candidates for neoadjuvant therapy include patients with inflammatory breast cancer and those in whom residual disease may prompt a change in therapy. Neoadjuvant therapy can also be used to reduce the extent of local therapy or reduce delays in initiating therapy. Although tumor histology, grade, stage, and estrogen, progesterone, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression should routinely be used to guide clinical decisions, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of other markers or genomic profiles. Patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who have clinically node-positive and/or at least T1c disease should be offered an anthracycline- and taxane-containing regimen; those with cT1a or cT1bN0 TNBC should not routinely be offered neoadjuvant therapy. Carboplatin may be offered to patients with TNBC to increase pathologic complete response. There is currently insufficient evidence to support adding immune checkpoint inhibitors to standard chemotherapy. In patients with hormone receptor (HR)-positive (HR-positive), HER2-negative tumors, neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be used when a treatment decision can be made without surgical information. Among postmenopausal patients with HR-positive, HER2-negative disease, hormone therapy can be used to downstage disease. Patients with node-positive or high-risk node-negative, HER2-positive disease should be offered neoadjuvant therapy in combination with anti-HER2-positive therapy. Patients with T1aN0 and T1bN0, HER2-positive disease should not be routinely offered neoadjuvant therapy.

Additional information is available at www.asco.org/breast-cancer-guidelines.

INTRODUCTION

Adjuvant or postoperative systemic therapy is the mainstay of treatment for early-stage breast cancer. The term neoadjuvant refers to the use of systemic therapy prior to surgery. Neoadjuvant therapy was initially used in breast cancer for the treatment of inoperable, locally advanced disease.1 Subsequently, the role of neoadjuvant therapy in patients with operable breast cancer has been extensively investigated. Building on the finding that systemic treatment could render some inoperable patients eligible for surgery, there was interest in using preoperative systemic therapy to reduce the extent and morbidity of curative surgery. Multiple studies of both chemotherapy and endocrine therapy have shown that neoadjuvant treatment can increase the likelihood of breast-conserving surgery,2-5 establishing neoadjuvant treatment as a viable option in patients with operable disease.

Additionally, as the goal of adjuvant treatment is to eradicate micrometastatic disease and prevent distant recurrence, there was interest in studying whether delivering systemic treatment earlier could further reduce the likelihood of metastatic disease. Two large studies completed in the 1990s by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP; studies B-18 and B-27) investigated whether administering chemotherapy prior to surgery would improve outcomes compared with adjuvant treatment.2,3 These studies showed no difference in disease-free survival (DFS) or overall survival (OS) based on the timing of systemic therapy. However, they did show that patients who achieved a pathologic complete response (pCR) had a significantly better prognosis than those who had residual disease, and long-term data from these trials and subsequent meta-analyses suggested that there may be subpopulations of patients who experienced benefit from neoadjuvant treatment.6 The CTNeoBC pooled analysis of neoadjuvant breast cancer clinical trials published in 2014 confirmed that achievement of a pCR with neoadjuvant treatment was prognostic, and it also showed that the association between pCR and outcomes was strongest in patients with triple-negative and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive disease.7,8

More recently, interest in neoadjuvant therapy has focused on examining the role of response to neoadjuvant treatment as a predictive marker. The question of whether improvement in pCR from the addition of a particular treatment translates to a benefit in long-term outcome has generated substantial controversy. In the trial-level analysis of CTNeoBC, there was no significant association between an increase in the rate of pCR with specific therapies and event-free survival, and thus a predictive effect could not be confirmed.7 It should be noted that therapeutic neoadjuvant trials that include pCR or change in a biomarker, such as Ki67, as the primary end point are often done to guide drug development, and are not meant to change the standard of care until confirmatory trials evaluating survival outcomes are performed. These proof-of-principle studies will not be discussed in detail in this guideline and are not intended to change routine practice.

As our understanding of the biology of breast cancer has evolved in recent decades, it has become clear that optimal therapy for breast cancer is driven by subtype. Thus, older neoadjuvant trials that used a one-size-fits-all approach to therapy selection are less relevant in the current era of biologically driven treatment selection. As noted, it has long been known that patients with triple-negative and HER2-positive disease are more likely to achieve pCR with neoadjuvant treatment. In this context, a number of recent trials have focused on using a lack of response to neoadjuvant therapy to identify patients who have a worse prognosis and could therefore benefit from additional adjuvant treatment.9,10

The purpose of this guideline is to develop recommendations concerning the optimal use of systemic neoadjuvant therapy, including chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and targeted therapy for patients with invasive breast cancer. The Expert Panel strongly advocates for a multidisciplinary team management approach when considering neoadjuvant therapy for patients with breast cancer. The guideline outlines recommendations based on clinical presentation, patient characteristics, and breast cancer subtype.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy, Endocrine Therapy, and Targeted Therapy for Breast Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline

Guideline Question

What is the optimal use of neoadjuvant therapy for women with invasive, nonmetastatic breast cancer?

Target Population

Patients with nonmetastatic breast cancer.

Target Audience

Medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, oncology nurses, patients or caregivers or advocates, and oncology advanced practice providers.

Methods

An Expert Panel was convened to develop clinical practice guideline recommendations based on a systematic review of the medical literature.

CLINICAL QUESTION 1

Which patients with breast cancer are appropriate candidates for neoadjuvant systemic therapy?

Recommendations

Recommendation 1.1.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the treatment of choice for patients with inflammatory breast cancer or those with unresectable or locally advanced disease at presentation whose disease may be rendered resectable with neoadjuvant treatment (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.2.

Tumor histology, grade, stage and estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 expression should routinely be used to guide clinical decisions as to whether or not to pursue neoadjuvant chemotherapy. There is insufficient evidence to support the use of other immunochemical markers, morphological markers (eg, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes) or genomic profiles to guide a clinical decision as to whether or not to pursue neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: insufficient; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 1.3.

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy should be offered to patients with high-risk HER2-positive or triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) in whom the finding of residual disease would guide recommendations related to adjuvant therapy (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.4.

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy may be offered to reduce the extent of surgery (breast-conserving surgery and axillary lymph node dissection). Chemotherapy with or without targeted therapy, or endocrine therapy (if hormone receptor–positive [HR-positive]) may be offered (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 1.5.

In patients for whom a delay in surgery is preferable (eg, for genetic testing required for surgical treatment decision making, to allow time to consider reconstructive options) or unavoidable, neoadjuvant systemic therapy may be offered (Type: informal consensus; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

CLINICAL QUESTION 2

How should response be measured in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy?

Recommendations

Recommendation 2.1.

Patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy should be monitored for response with clinical examination at regular intervals. Breast imaging may be used to confirm clinical suspicion of progression and for surgical planning. When imaging is used, the modality that was most informative at baseline—mammography, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging—should be used at follow-up (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: insufficient; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 2.2.

Blood- and tissue-based biomarkers should not be used for monitoring patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: insufficient; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 2.3.

Pathologic complete response (pCR), defined as absence of invasive disease in breast and lymph nodes, should be used to measure response to guide clinical decision making (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: insufficient; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

CLINICAL QUESTION 3

What neoadjuvant systemic therapy regimens are recommended for patients with TNBC?

Recommendations

Recommendation 3.1.

Patients with TNBC who have clinically node-positive and/or at least T1c disease should be offered an anthracycline- and taxane-containing regimen in the neoadjuvant setting (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 3.2.

Patients with cT1a or cT1bN0 TNBC should not routinely be offered neoadjuvant therapy outside of a clinical trial (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 3.3.

Carboplatin may be offered as part of a neoadjuvant regimen in patients with TNBC to increase likelihood of pCR. The decision to offer carboplatin should take into account the balance of potential benefits and harms (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 3.4.

There is insufficient evidence to recommend routinely adding the immune checkpoint inhibitors to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early-stage TNBC (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

CLINICAL QUESTION 4

What neoadjuvant treatment is recommended for patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer?

Recommendations

Recommendation 4.1.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be used instead of adjuvant chemotherapy in any patient with HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer in whom the chemotherapy decision can be made without surgical pathology data and/or tumor-specific genomic testing (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 4.2.

For postmenopausal patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative disease, neoadjuvant endocrine therapy with an aromatase inhibitor may be offered to increase locoregional treatment options. If there is no intent for surgery, endocrine therapy may be used for disease control (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 4.3.

For premenopausal patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative early-stage disease, neoadjuvant endocrine therapy should not be routinely offered outside of a clinical trial (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

CLINICAL QUESTION 5

What neoadjuvant treatment is recommended for patients with HER2-positive disease?

Recommendations

Recommendation 5.1.

Patients with node-positive or high-risk node-negative, HER2-positive disease should be offered neoadjuvant therapy with an anthracycline and taxane or non–anthracycline-based regimen in combination with trastuzumab. Pertuzumab may be used with trastuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting (Type: evidence-based, benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 5.2.

Patients with T1a N0 and T1b N0, HER2-positive disease should not be routinely offered neoadjuvant chemotherapy or anti-HER2 agents outside of a clinical trial (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Additional Resources

More information, including a supplement with additional evidence tables, slide sets, and clinical tools and resources, is available at www.asco.org/breast-cancer-guidelines. The Methodology Manual (available at www.asco.org/guideline-methodology) provides additional information about the methods used to develop this guideline. Patient information is available at www.cancer.net.

ASCO believes that cancer clinical trials are vital to inform medical decisions and improve cancer care, and that all patients should have the opportunity to participate.

GUIDELINE QUESTIONS

This clinical practice guideline addresses five overarching clinical questions: (1) Which patients with breast cancer are appropriate candidates for neoadjuvant systemic therapy? (2) How should response be measured in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy? (3) What neoadjuvant systemic therapy regimens are recommended for patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)? (4) What neoadjuvant treatment is recommended for patients with HER2-negative/HR-positive breast cancer? (5) What neoadjuvant treatment is recommended for patients with HER2-positive disease?

METHODS

Guideline Development Process

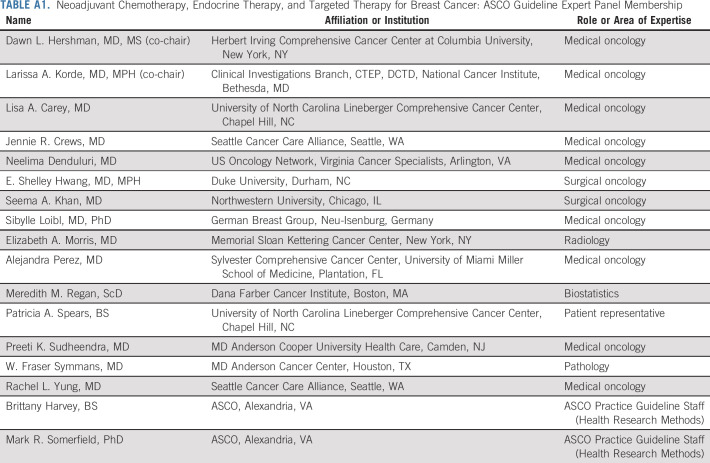

This systematic review-based guideline product was developed by a multidisciplinary Expert Panel, which included a patient representative and ASCO guidelines staff with health research methodology expertise. The Expert Panel met face-to-face and via teleconference and/or webinar and corresponded through e-mail. Based upon the consideration of the evidence, the authors were asked to contribute to the development of the guideline, provide critical review, and finalize the guideline recommendations. The guideline recommendations were sent for an open comment period of 2 weeks (August 28, 2020, through September 8, 2020) allowing the public to review and comment on the recommendations after submitting a confidentiality agreement. These comments were taken into consideration while finalizing the recommendations. Members of the Expert Panel were responsible for reviewing and approving the penultimate version of the guideline, which was then circulated for external review, and submitted to the Journal of Clinical Oncology (JCO) for editorial review and consideration for publication. All ASCO guidelines are ultimately reviewed and approved by the Expert Panel and the ASCO Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee prior to publication. All funding for the administration of the project was provided by ASCO.

The recommendations were developed by using a systematic review (January 1, 2000-August 31, 2020) of randomized phase II and phase III clinical trials (RCTs) in PubMed. The search was restricted to articles published in English, and to systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials that reported on pCR and survival end points. (Broader outcome criteria, including clinical tumor objective response, were used for studies of neoadjuvant endocrine therapy.) The electronic literature searches were supplemented by articles from Panel members' personal files to inform selected clinical questions for which no contemporary or directly relevant RCTs were available. The ASCO Guidelines Methodology Manual (available at www.asco.org/guideline-methodology) provides additional information about the guideline development process.

This is the most recent information as of the publication date. Articles were excluded from the systematic review if they were (1) meeting abstracts not subsequently published in peer-reviewed journals; (2) editorials, commentaries, letters, news articles, case reports, and narrative reviews; (3) published in a non-English language; (4) RCTs with < 100 patients total across treatment arms; (5) trials that evaluated only clinical response, biomarker end points, or breast-conserving surgery (BCS) feasibility or rates; and (6) reports of exploratory or secondary analyses. Based on the implementability review, revisions were made to the draft to clarify recommended actions for clinical practice. Ratings for the type and strength of recommendation, evidence, and potential bias are provided with each recommendation. The ASCO Expert Panel and guidelines staff will work with cochairs to keep abreast of any substantive updates to the guideline. Based on formal review of the emerging literature, ASCO will determine the need for updates.

Guideline Disclaimer

The Clinical Practice Guidelines and other guidance published herein are provided by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Inc (ASCO) to assist providers in clinical decision making. The information herein should not be relied upon as being complete or accurate, nor should it be considered as inclusive of all proper treatments or methods of care or as a statement of the standard of care. With the rapid development of scientific knowledge, new evidence may emerge between the time information is developed and when it is published or read. The information is not continually updated and may not reflect the most recent evidence. The information addresses only the topics specifically identified therein and is not applicable to other interventions, diseases, or stages of diseases. This information does not mandate any particular course of medical care. Further, the information is not intended to substitute for the independent professional judgment of the treating provider, as the information does not account for individual variation among patients. Recommendations reflect high, moderate, or low confidence that the recommendation reflects the net effect of a given course of action. The use of words like “must,” “must not,” “should,” and “should not” indicates that a course of action is recommended or not recommended for either most or many patients, but there is latitude for the treating physician to select other courses of action in individual cases. In all cases, the selected course of action should be considered by the treating provider in the context of treating the individual patient. Use of the information is voluntary. ASCO provides this information on an “as is” basis and makes no warranty, express or implied, regarding the information. ASCO specifically disclaims any warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular use or purpose. ASCO assumes no responsibility for any injury or damage to persons or property arising out of or related to any use of this information, or for any errors or omissions.

Guideline and Conflicts of Interest

The Expert Panel was assembled in accordance with ASCO's Conflict of Interest Policy Implementation for Clinical Practice Guidelines (“Policy,” found at http://www.asco.org/rwc). All members of the Expert Panel completed ASCO's disclosure form, which requires disclosure of financial and other interests, including relationships with commercial entities that are reasonably likely to experience direct regulatory or commercial impact as a result of promulgation of the guideline. Categories for disclosure include employment; leadership; stock or other ownership; honoraria, consulting, or advisory role; speaker's bureau; research funding; patents, royalties, other intellectual property; expert testimony; travel, accommodations, expenses; and other relationships. In accordance with the Policy, the majority of the members of the Expert Panel did not disclose any relationships constituting a conflict under the Policy.

RESULTS

A total of 46 articles representing 36 unique RCTs met eligibility criteria and form the evidentiary basis for the guideline recommendations. The randomized phase II and III trials included in the review are summarized in the Data Supplement Table 1 (online only).9-25,26-55 The included RCTs addressed the use of neoadjuvant systemic therapy in patients with high-risk HER2-positive or TNBC; specific neoadjuvant systemic therapy regimens in patients with TNBC; use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of early-stage TNBC; neoadjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal patients with HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer; preoperative endocrine therapy for premenopausal patients with HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer; neoadjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive or high-risk node-negative, HER2-positive disease; and, more broadly, the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens in nonmetastatic breast cancer. The electronic search identified 20 meta-analyses5,56-68 that provided confirmatory, supplementary evidence (Table 2 in the Data Supplement, online only).

Study quality was formally assessed for the 29 phase III RCTs identified (Table 3 in the Data Supplement, online only). Design aspects related to the individual study quality were assessed by one reviewer, with factors such as blinding, allocation concealment, placebo control, intention to treat, funding sources, etc, generally indicating a low to intermediate potential risk of bias for most of the identified evidence. Follow-up times varied between studies, lowering the comparability of the results. Refer to Methodology Manual for definitions of ratings for overall potential risk of bias.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Clinical Question 1

Which patients with breast cancer are appropriate candidates for neoadjuvant systemic therapy?

Recommendation 1.1.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the treatment of choice for patients with inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) or those with unresectable or locally advanced disease at presentation whose disease may be rendered resectable with neoadjuvant treatment (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.2.

Tumor histology, grade, stage and estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 expression should routinely be used to guide clinical decisions as to whether or not to pursue neoadjuvant chemotherapy. There is insufficient evidence to support the use of other immunochemical markers, morphological markers (eg, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes [TILs]), or genomic profiles to guide a clinical decision as to whether or not to pursue neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: insufficient; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 1.3.

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy should be offered to patients with high-risk HER2-positive or TNBC in whom the finding of residual disease would guide recommendations related to adjuvant therapy (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.4.

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy may be offered to reduce the extent of surgery (BCS and axillary lymph node dissection). Chemotherapy with or without targeted therapy, or endocrine therapy (if HR-positive) may be offered (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 1.5.

In patients for whom a delay in surgery is preferable (eg, for genetic testing required for surgical treatment decision making, to allow time to consider reconstructive options) or unavoidable, neoadjuvant systemic therapy may be offered (Type: informal consensus; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and analysis.

Patients with inoperable locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) or IBC. There are no modern large randomized clinical trials that focus specifically on patients with IBC or LABC, and these patients are often excluded from trials of adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy. The recommendation for neoadjuvant therapy in these patients represents the best clinical opinion of the Expert Panel based on data from phase II trials, older published nonrandomized data, expert consensus opinion, and clinical experience.

Clinical interpretation.

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy offers a range of potential advantages for patients with LABC or IBC, including downstaging of the primary tumor to bring to operability; more prompt treatment of subclinical distant micrometastases; and enhanced ability to evaluate in vivo the response of the tumor to particular systemic agents.69

Literature review and analysis.

Use of immunohistochemical markers or genomic profiles to guide neoadjuvant therapy clinical decisions. There are no randomized trials that directly address the use of genomic profiles to guide neoadjuvant therapy decisions. The Expert Panel's recommendation against the use of nonroutine immunohistochemical markers, morphological markers (eg, TILs), or genomic profiles to guide clinical decision making regarding neoadjuvant chemotherapy represents the best clinical opinion of the Expert Panel based on the currently limited prospective data.

Clinical interpretation.

Both Oncotype DX Recurrence Score and MammaPrint have been shown to predict benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, and retrospective studies reported that high-risk Oncotype DX Recurrence Score may be associated with a higher pCR rate.70 However, no prospective trials have assessed the clinical utility of genomic markers for determining whether patients should receive their systemic chemotherapy prior to surgery or for selecting a chemotherapy regimen. Estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 expression are routinely used in practice to guide use of targeted therapies. Other immunochemical markers, morphological markers, and genomic profile markers have been used in research, but do not have sufficient evidence to support their use for guiding neoadjuvant therapy clinical decision making.

Literature review and analysis.

Use of neoadjuvant systemic therapy in patients with high-risk HER2-positive or TNBC. The systematic review identified two studies that support the use of neoadjuvant systemic therapy in patients with high-risk HER2-positive or TNBC in whom the finding of residual disease would prompt a change in adjuvant therapy. The Capecitabine for Residual Cancer as Adjuvant Therapy (CREATE-X) open-label, phase III trial10 evaluated the safety and efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with HER2-negative primary breast cancer who had residual invasive disease after they had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy that contained taxane, anthracycline, or both. CREATE-X randomly assigned 910 patients to receive standard postoperative adjuvant treatment either with capecitabine or without. Analyses revealed that adjuvant capecitabine prolonged both DFS and OS. In safety analyses, the most frequent adverse event observed in the capecitabine group was hand-foot syndrome; this occurred in 325 of 443 patients (73.4%). In the subset of patients with triple-negative disease—about 30% of patients studied—the DFS rate was 69.8% among patients who received capecitabine versus 56.1% in the control group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; 95% CI, 0.39 to 0.87); the OS rate was 78.8% versus 70.3% (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.30 to 0.90). In the subset of patients with HR-positive breast cancer, there were numerical improvements in DFS and OS that did not meet statistical significance. The DFS rate was 76.4% in the capecitabine group and 73.4% in the control group (HR for recurrence, second, cancer, or death, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.55 to 1.17), and OS rates were 93.4% and 90%, respectively (HR for death, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.38 to 1.40).

The KATHERINE open-label, phase III clinical trial compared adjuvant trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) with trastuzumab in patients with stage I to III, HER2-positive breast cancer who had residual invasive disease in the breast or axilla after completing neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus HER2-targeted therapy.9 Patients were randomly assigned to receive either postoperative T-DM1 (n = 743) at a dose of 3.6 mg per kilogram of body weight, or trastuzumab (n = 743) at a dose of 6 mg per kilogram intravenously every 3 weeks for 14 cycles (42 weeks). A majority of patients (80%) received trastuzumab as their sole HER2-targeted therapy in the neoadjuvant setting; approximately 18% received dual neoadjuvant HER2-targeted therapy with trastuzumab and pertuzumab. Invasive disease or death occurred in 91 (12.2%) of patients who received adjuvant T-DM1 and in 165 (22.2%) patients who received trastuzumab. The estimated invasive DFS at 3 years was significantly higher in the T-DM1 group than in the trastuzumab group (88.3% v 77%; HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.39 to 0.64; P < .001). Similarly, the risk of distant recurrence was lower in patients who received T-DM1 than in patients who received trastuzumab (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.45 to 0.79). Grade 3 or higher adverse events occurred in 190 (25.7%) patients who received T-DM1 and in 111 (15.4%) of patients who received trastuzumab, including thrombocytopenia (5.7% v 0.3%) and peripheral sensory neuropathy (1.4% v 0%). Serious adverse events occurred in 94 patients (12.7%) in the T-DM1 group and in 58 patients (8.1%) in the trastuzumab group. Adverse events leading to discontinuation of T-DM1 included thrombocytopenia, elevated liver function test abnormalities, and peripheral sensory neuropathy. Patients who were unable to complete T-DM1 received trastuzumab to complete a year of HER2-targeted therapy.

Clinical interpretation.

The CREATE-X and KATHERINE trials establish that, in patients with TNBC or HER2-positive disease, the presence or absence of residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy alters treatment recommendations in the adjuvant setting. Thus, neoadjuvant therapy is the treatment of choice in all but small, node-negative, TNBC, or HER2-positive tumors.

Literature review and analysis.

Neoadjuvant therapy to reduce local therapy. A response to neoadjuvant therapy can result in downstaging of a tumor and therefore can improve tumor resectability, enhance cosmesis, and reduce postoperative complications.71 Evidence for the reduction in the extent of local therapy associated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy comes from several large-scale randomized trials that compared neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early-stage breast cancer. The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP B-18),72,73 the European Cooperative Trial in Operable breast cancer trial,74 and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 10902,75 all reported increased rates of BCS with neoadjuvant, compared with adjuvant chemotherapy. A number of Phase III neoadjuvant studies, including CALGB 40601,76 CALGB 40603,77 and BrighTNess,4 included prespecified secondary analyses to assess whether patients deemed not to be candidates for BCS at baseline were able to be converted to BCS. In these trials, the conversion rate from BCS-ineligible to BCS-eligible ranged from 43% to 53%.

There are fewer studies that address the use of neoadjuvant treatment to reduce axillary surgery. Limited data indicate that in patients with nodal metastases, downstaging because of neoadjuvant chemotherapy may allow for less extensive surgery for the axilla and thereby reduce surgical complications such as lymphedema and dysesthesias.78-80 Because the randomized trials that directly address this question are ongoing, the recommendation for neoadjuvant therapy to permit less extensive surgery on the axilla thus represents the best clinical opinion of the Expert Panel based on personal experience in breast cancer management.

Clinical interpretation.

For resectable disease, neoadjuvant systemic therapy with appropriate adjuvant regimens improves breast conservation rates and may reduce the need for axillary lymphadenectomy. In HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer, neoadjuvant endocrine therapy has similar clinical response rates to chemotherapy and is a reasonable option. However, tumor eradication in either the breast or axillary lymph nodes is rare for this tumor subtype.

Literature review and analysis.

Neoadjuvant therapy in cases of surgical delay. There are no randomized trials that directly address the use of neoadjuvant therapy as a bridge to delayed surgery. The recommendation that neoadjuvant therapy can be used when a surgical delay is preferred or necessary represents the best clinical opinion of the Expert Panel based on personal experience in breast cancer management.

Clinical interpretation.

In resource-constrained settings and during public health crises such as the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, there can be limited access to healthcare resources, including surgery. In these situations, neoadjuvant therapy can be used both to control local disease and prevent distant spread of disease until surgery can be performed.81,82

Additionally, there are clinical situations in which a delay of surgery, although not absolutely necessary, may be preferred. For example, if a patient with a clear indication for chemotherapy has a suspected BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and is considering bilateral mastectomy, it may be reasonable to delay surgery until genetic testing results are available or until reconstructive options can be discussed. In this scenario, as neoadjuvant therapy and adjuvant therapy have been shown to be equivalent in terms of long-term outcomes,2 neoadjuvant therapy may be considered.

Clinical Question 2

How should response be measured in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy?

Recommendation 2.1.

Patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy should be monitored for response with clinical examination at regular intervals. Breast imaging may be used to confirm clinical suspicion of progression and for surgical planning. When imaging is used, the modality that was most informative at baseline—mammography, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging—should be used at follow-up (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: insufficient; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 2.2.

Blood- and tissue-based biomarkers should not be used for monitoring patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: insufficient; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 2.3.

pCR, defined as absence of invasive disease in breast and lymph nodes, should be used to measure response to guide clinical decision making (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: insufficient; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and analysis.

There are no data from randomized trials informing the optimal methods for monitoring response during treatment. The recommendations for the frequency and character of monitoring clinical, radiologic, and pathologic response and for management of progressive disease (PD) reflect the best clinical opinion of the Expert Panel based on personal experience in breast cancer management.

Clinical interpretation.

For patients favoring BCS after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, strong consideration should be given to performing imaging, both at baseline and at completion of chemotherapy for optimal surgical planning.83 However, there is no evidence to support the benefit of routine imaging for progression, because of the infrequent nature of PD. If PD is suspected clinically, additional imaging is recommended for confirmation. Imaging should be performed with the same modality that was used for baseline assessment; studies have shown that MRI provides the most accurate objective measure of extent of disease.83,84 If there is evidence of clinical progression, then a multidisciplinary decision should be made regarding switching therapies or proceeding to locoregional intervention.

There are no data regarding the use of blood markers (eg, CA27-29 and CA15-3) for monitoring response to treatment, and these are not recommended for use in the neoadjuvant setting. Several studies have evaluated the association between early reductions in biomarkers (eg, Ki67) and improved breast cancer outcomes; however, these approaches are used for research purposes and to justify the evaluation of new therapeutic approaches, and are not meant to guide routine clinical care.85

Most neoadjuvant studies use pCR as the primary end point. However, there is substantial variation as to whether residual noninvasive disease is included in the definition of pCR. In the KATHERINE and CREATE-X studies, pCR was defined as a lack of residual invasive disease. Studies have also evaluated and validated the use of residual cancer burden and yP American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging prognostic factors associated with long-term breast cancer outcomes.86,87 There is scant evidence from randomized clinical trials to inform the question of how progression on neoadjuvant treatment is defined and managed, as trials have not had a consistent approach. Progression while on neoadjuvant treatment is rare and not well studied; in the largest reported series, only 3% of patients had confirmed PD, with over half of progressing patients demonstrating PD within the first two cycles of neoadjuvant treatment.88 However, progression during neoadjuvant chemotherapy is associated with a significantly worse progression-free survival and OS,88 highlighting the importance of clinical monitoring during treatment.

Although there have been no clinical trials that have compared different methodologies for examining the tumor bed, there is a wealth of data that show that the finding of pCR (whether defined as absence of invasive disease or absence of invasive and noninvasive disease in breast and lymph nodes) is associated with a favorable prognosis. Importantly, pCR is critical for determining the need for additional adjuvant therapy in TNBC and HER2-positive breast cancer. When surgery is performed after neoadjuvant systemic treatment, meticulous clinical, radiologic, and pathologic correlation should be performed to ensure that the tumor bed has been examined thoroughly for residual disease, and extent of disease in the breast and axilla should be indicated in the pathology report using yP AJCC staging. Information from imaging and localization markers inserted is particularly helpful for accurate pathology evaluation of mastectomy specimens, and specimen radiography is an important capability to direct that sampling.

Clinical Question 3

What neoadjuvant systemic therapy regimens are recommended for patients with TNBC?

Recommendation 3.1.

Patients with TNBC who have clinically node-positive and/or at least T1c disease should be offered an anthracycline- and taxane-containing regimen in the neoadjuvant setting (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 3.2.

Patients with cT1a or cT1bN0 TNBC should not routinely be offered neoadjuvant therapy outside of a clinical trial (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 3.3.

Carboplatin may be offered as part of a neoadjuvant regimen in patients with TNBC to increase likelihood of pCR. The decision to offer carboplatin should take into account the balance of potential benefits and harms (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 3.4.

There is insufficient evidence to recommend routinely adding the immune checkpoint inhibitors to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early-stage TNBC (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and analysis.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with TNBC. There is no direct evidence from phase III randomized clinical trials regarding the optimal neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen in patients with TNBC. However, there is broad consensus based on key randomized clinical trials6 and an individual patient data meta-analysis89 that chemotherapy regimens appropriate for adjuvant treatment by stage are also appropriate for neoadjuvant treatment. On this basis, the Expert Panel recommends that patients with clinically node-positive and/or at least T1c TNBC be offered an anthracycline- and taxane-based neoadjuvant regimen.

There is less agreement concerning the addition of carboplatin to the standard anthracycline-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen in patients with TNBC. In high-risk patients, the addition of platinum to the standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen of paclitaxel and AC (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide) or EC (epirubicin and cyclophosphamide) has been shown consistently to improve pCR rates,11-13,56,57,59 by up to 20%.90 The meta-analysis by Poggio et al56 of nine RCTs (2,109 patients) that evaluated the safety and efficacy of platinum-based versus platinum-free neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with TNBC found, for instance, that platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy increased pCR rates significantly from 37.0% to 52.1% (odds ratio [OR], 1.96; 95% CI, 1.46 to 2.62, P < .001). Not surprisingly, there was a significantly greater risk of grade 3 and 4 hematological adverse events observed with platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Petrelli et al59 found a similar increased pCR rate in a meta-analysis of RCTs that investigated platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in TNBC. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy that contained carboplatin or cisplatin significantly increased the pCR rate compared with non–platinum-containing neoadjuvant chemotherapy (relative risk [RR], 1.45; 95% CI, 1.25 to 1.68; P < .0001).

However, the effect of adding platinums on long-term outcomes such as DFS and OS is much less certain.91 None of the relevant trials has been adequately powered to evaluate survival outcomes. In CALGB 40603 (Alliance),12 carboplatin significantly improved pCR breast or axilla (54% v 41%, P = .0029) in patients with stage II-III TNBC when added to weekly paclitaxel for 12 weeks followed by AC once every 2 weeks for four cycles. In patients who received carboplatin, grade ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia and neutropenia occurred more commonly; these patients were also more likely to require dose modification, skipped doses, or early treatment discontinuation because of toxicity. Patients who achieved a pCR had improved event-free survival and OS compared with patients who did not achieve a pCR at a median 3-year follow-up.92 There was no improvement in survival outcome, however, with the addition of carboplatin to the standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen.

The GeparSixto randomized phase II clinical trial included patients with stage II or III HER2-positive (n = 273) or TNBC (n = 315). Patients received 18 weeks of neoadjuvant weekly paclitaxel, weekly nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin, and bevacizumab every 21 days, and were randomly assigned to either concurrent weekly carboplatin or no additional treatment. Those who received carboplatin had an improvement in pCR (pCR 53.2% with carboplatin v 36.9% without carboplatin, P = .005).13 Treatment discontinuation was more frequent in patients who received carboplatin than in those who did not receive carboplatin (48% v 39%).

Loibl et al11 reported the results of a phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (BrighTNess) that evaluated the addition of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, veliparib, and carboplatin or carboplatin alone compared with standard neoadjuvant taxane-based chemotherapy followed by AC in patients with stage II-III TNBC. The study randomly assigned 316 patients to paclitaxel plus carboplatin plus veliparib; 160 patients to paclitaxel plus carboplatin; and 158 patients to paclitaxel alone. The pCR rates were 58% in patients who received paclitaxel and carboplatin; 53% in patients who received paclitaxel, carboplatin, and veliparib; and 31% in patients who received paclitaxel alone. The difference between the latter two groups was statistically significant (P < .0001). Not surprisingly, grade 3 or 4 toxicities (eg, anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia) occurred more frequently among patients who received carboplatin. Event-free survival and OS were secondary end points in this trial and have not been reported yet.

Literature review and analysis.

Use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of early-stage TNBC. There has been increasing interest in studying the efficacy and safety of immunotherapy in many solid tumors, breast cancer among them.93 Pembrolizumab and atezolizumab have both been studied in the metastatic setting, and atezolizumab is FDA-approved for first-line treatment of PD-L1–positive TNBC and several phase II trials have suggested increased pCR rates.94 The systematic literature review conducted for this guideline identified two phase III randomized clinical trials that addressed the role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of nonmetastatic TNBC.14,51 The KEYNOTE-522 randomized, double-blind, phase III trial evaluated the combination of carboplatin or paclitaxel with or without pembrolizumab followed by AC with or without pembrolizumab in patients with stage II or stage III TNBC.14 At the second interim analysis with a median duration of follow-up of 15.5 months, the data showed that adding pembrolizumab to carboplatin or paclitaxel significantly improved pCR rates. The percentage of patients with a pCR in the pembrolizumab plus neoadjuvant chemotherapy group was 64.8% (260 of 401 patients) versus 51.2% in the placebo plus neoadjuvant chemotherapy group (103 of 201 patients; estimated treatment difference, 13.6 percentage points; 95% CI, 5.4 to 21.8; P < .001). The investigators also reported the preliminary event-free survival rate in the two arms with 104 of the 327 expected events needed for the final analysis. The estimated percentage of patients at 18 months who were alive without disease progression that precluded definitive surgery, without local or distant recurrence and without a second primary tumor, was 91.3% (95% CI, 88.8 to 93.3) for patients in the pembrolizumab-chemotherapy group and was 85.3% (95% CI, 80.3 to 89.1) for patients in the placebo-chemotherapy group. Treatment-related adverse events that were grade 3 or higher occurred in 76.8% and 72.2% of the patients in the pembrolizumab-chemotherapy group and the placebo-chemotherapy group, respectively. The most commonly occurring grade 3 or greater adverse events in both treatment groups were anemia, neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, and decreased neutrophil count. Hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency were more commonly noted in patients who received pembrolizumab.

The IMpassion031 randomized, double-blind, phase III neoadjuvant treatment trial evaluated atezolizumab versus placebo combined with nab-paclitaxel followed by AC in patients with early-stage TNBC.51 Analyses revealed that adding atezolizumab to nab-paclitaxel followed by AC improved the pCR rate significantly irrespective of patients' PD-L1 status: pCR was observed in 95 of 165 patients in the atezolizumab plus chemotherapy group (58%; 95% CI, 50 to 65) versus in 69 of 168 patients in the placebo plus chemotherapy group (41%; 34 to 49; rate difference 17%, 95% CI, 6 to 27; one-sided P = .0044). The trial was not powered for long-term survival outcomes (event-free survival and OS). Serious, treatment-related adverse events occurred in 37 (23%) patients in atezolizumab plus chemotherapy group and in 26 (16%) patients in chemotherapy plus placebo group. Commonly reported (≥ 20% incidence) adverse events were similar between the two treatment groups and mostly driven by chemotherapy effects.

Clinical interpretation.

The choice of neoadjuvant regimen should be appropriate to the stage and subtype of disease. Outside of a clinical trial, regimens for neoadjuvant treatment of TNBC mirror the adjuvant regimens, and generally involve polychemotherapy with both an anthracycline and a taxane. The addition of platinum agents during the taxane component augments the pCR rate so may be considered for high clinical risk, for example, node-positive disease; however, it is not known whether the addition of platinum improves invasive DFS or OS. In lower-risk patients or those with cardiac risk factors in whom the risks associated with an anthracycline may be more worrisome, a taxane-based regimen such as docetaxel plus cyclophosphamide or carboplatin given for six cycles may be substituted.95 Immune checkpoint inhibitors added to chemotherapy in TNBC may augment pCR, although long-term outcomes and toxicity in patients receiving these drugs in the neoadjuvant setting are still undergoing evaluation.

Clinical Question 4

What neoadjuvant treatment is recommended for patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer?

Recommendation 4.1.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be used instead of adjuvant chemotherapy in any patient with HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer in whom the chemotherapy decision can be made without surgical pathology data and/or tumor-specific genomic testing (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 4.2.

For postmenopausal patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative disease, neoadjuvant endocrine therapy with an aromatase inhibitor may be offered to increase locoregional treatment options. If there is no intent for surgery, endocrine therapy may be used for disease control (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 4.3.

For premenopausal patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative early-stage disease, neoadjuvant endocrine therapy should not be routinely offered outside of a clinical trial (Type: evidence-based; benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and analysis.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer. There is no direct evidence from randomized phase III clinical trials to inform a recommendation regarding the optimal neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen in patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer. The recommendation that neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be used instead of adjuvant chemotherapy in any patient with HR-positive/HER2-negative disease is based on extrapolation from data from the landmark NSABP B-18 trial,2 which showed no difference between adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment in DFS or OS in patients with stage II or stage III breast cancer who were randomly assigned to AC either before or after surgery. In general, the same patient and disease factors that are used to guide adjuvant systemic therapy decision making (eg, nodal status, tumor grade, and comorbidities) can be used to select patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative disease for whom neoadjuvant chemotherapy is appropriate.96 However, it is recognized that some factors, such as nodal status, may be better assessed following definitive surgery in some patients. Further, as noted in Recommendation 1.2 in the present guideline, the clinical utility of immunohistochemical markers such as Ki67 and genomic predictors such as Oncotype Dx Recurrence Score has not been definitively determined in the neoadjuvant setting, and these markers should not be used routinely to determine the sequence surgery and systemic therapy.

Literature review and analysis.

Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer. The systematic literature review identified two randomized clinical trials15,52 and one meta-analysis5 that inform the question of neoadjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer. The IMPACT (Immediate Preoperative Anastrozole, Tamoxifen, or Combined With Tamoxifen) double-blind clinical trial randomly assigned 330 postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor–positive (ER-positive), nonmetastatic, invasive, operable breast cancer to neoadjuvant anastrozole (n = 113), tamoxifen (n = 108), or a combination of anastrozole and tamoxifen (n = 109).15 There were no statistically significant differences among the three treatment groups in tumor objective response, the primary end point of the trial (anastrozole, 37%; tamoxifen, 36%; and the combination, 39%). Analyses of data on surgical outcomes revealed that among patients initially thought to require mastectomy, a significantly higher proportion of patients were deemed by their surgeon to be eligible for BCS after treatment with anastrozole (46%) versus with tamoxifen (22%, P = .03). Semiglazov et al52 compared randomly assigned patients to either neoadjuvant endocrine therapy (anastrozole or exemestane) or chemotherapy (doxorubicin and taxane) for 3 months and showed equivalent rates of clinical objective response (64% in both arms), pCR (3% v 6%), and a slightly higher rate of breast-conserving surgery in the endocrine therapy arm (33% v 24%, P = .058).

Spring et al5 conducted a literature-based meta-analysis of 20 prospective, randomized clinical trials (3,490 unique patients) to evaluate the effects of neoadjuvant endocrine therapy on clinical response rate and BCS rates in patients with ER-positive breast cancer. Trials in the meta-analysis had to have included at least one neoadjuvant endocrine therapy arm. The primary end point was response rate, although the authors also extracted data on pCR and BCS rates, when reported. Eighteen of the 20 trials included only postmenopausal women; one included premenopausal women and postmenopausal women; and one trial included just premenopausal women. Neoadjuvant aromatase inhibitors were more effective (better clinical response rate and BCS rate) than tamoxifen based on analysis of the results of seven trials. There were no differences observed in clinical response rate between endocrine monotherapy and dual endocrine therapy. The meta-analysis also suggested that response rates and BCS rates with aromatase inhibitor-based neoadjuvant endocrine monotherapy were comparable with those observed with combination neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Toxicity was significantly greater in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy arms of the three studies examined.

Literature review and analysis.

Preoperative endocrine therapy for premenopausal patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer. The systematic review identified two randomized clinical trials that investigated preoperative endocrine therapy among premenopausal women with operable HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer.17,53 The Study of Tamoxifen or Arimidex, combined with Goserelin acetate, to compare Efficacy and safety (STAGE) evaluated neoadjuvant tamoxifen plus goserelin (n = 99) versus neoadjuvant anastrozole plus goserelin (n = 98) in premenopausal women with ER-positive, early-stage breast cancer.17 In the group that received anastrozole plus goserelin, 69 of 98 (70.4%) patients had a complete or partial response compared with 50 of 99 (50.5%) patients in the group that received tamoxifen plus goserelin (estimated difference between groups 19.9%, 95% CI, 6.5 to 33.3; P = .004). No significant differences were observed in the quality-of-life measures, although the study was not powered to detect differences in these outcome measures. Eighty-four percent of patients reported treatment-related adverse versus 77% of patients in the tamoxifen group. However, adjuvant trials report that ovarian function suppression with endocrine therapy is associated with more toxicity with prolonged use than tamoxifen alone.97

In a randomized phase III study, Kim et al53 compared 24 weeks of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with neoadjuvant endocrine therapy using tamoxifen and goserelin. The primary end point of the study was clinical response rate as determined by caliper measurement and MRI. The final analysis included 174 patients. Response rate was significantly higher in patients who received chemotherapy using both caliper measurement (83.9% v 71.3%, P = .046) and MRI (83.7% v 52.9%, P < .001). Grade 3 or worse treatment-related toxicities were reported in 19 patients on the chemotherapy arm and none on the endocrine therapy arm.

Literature review and analysis.

Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy for patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer who are not candidates for chemotherapy or surgery. There is no direct evidence from randomized clinical trials regarding the question of endocrine therapy among patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer who are either not candidates for chemotherapy or surgery or who decline these treatment options. The recommendation that endocrine therapy with or without intent for surgery may be offered to HR-positive/HER2-negative patients who are not candidates for chemotherapy or surgery represents the best clinical opinion of the Expert Panel based on personal experience in breast cancer management.98 Endocrine therapy without intent for surgery has typically been reserved for patients who are poor surgical candidates and medically unfit for chemotherapy.99,100 In this context, ASCO's geriatric assessment (GA) guideline has highlighted the importance of assessment of underlying health status for older patients using formal GA and life expectancy tools to help guide decisions regarding chemotherapy.101

Clinical interpretation.

For HR-positive/HER2-negative patients, neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be given if the tumor stage is such that chemotherapy will be given regardless of surgical timing; in this case, the same regimen should be used as would be considered following surgery.102 If pathologic information from the surgical resection (ie, nodal status) or a genomic profile is needed to determine whether or not chemotherapy is appropriate, neoadjuvant chemotherapy should not be used. The use of genomic assays to determine neoadjuvant chemotherapy vs neoadjuvant endocrine therapy has not been rigorously studied and is not recommended. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy with an aromatase inhibitor in postmenopausal women has similar activity as chemotherapy and can be considered in larger tumors for which tumor downstaging is desired; however, significant pathologic response is rare. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy has been studied less rigorously in premenopausal women, but existing data indicate that neoadjuvant endocrine therapy is likely less effective than chemotherapy if downstaging is desired. The optimal duration of neoadjuvant endocrine therapy is not known and accordingly should be individualized and guided by careful evaluation of the patient's clinical status and the clinical response over time. Most studies that reported downstaging of tumors with neoadjuvant endocrine therapy administered 3-6 months of treatment.

Clinical Question 5

What neoadjuvant treatment is recommended for patients with HER2-positive disease?

Recommendation 5.1.

Patients with node-positive or high-risk node-negative, HER2-positive disease should be offered neoadjuvant therapy with an anthracycline and taxane or non–anthracycline-based regimen in combination with trastuzumab. Pertuzumab may be used with trastuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting (Type: evidence-based, benefits outweigh harms; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 5.2.

Patients with T1a N0 and T1b N0, HER2-positive disease should not be routinely offered neoadjuvant chemotherapy or anti-HER2 agents outside of a clinical trial (Type: informal consensus; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and analysis.

Neoadjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive or high-risk node-negative, HER2-positive disease. Meta-analyses and RCTs of neoadjuvant therapy in patients with node-positive or high-risk node-negative, HER2-positive breast cancer support the use of an anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimen and trastuzumab, with or without pertuzumab for dual anti-HER2 blockade (ACTH ± P); or the use of a nonanthracycline chemotherapy and trastuzumab, again, with or without pertuzumab (TCH ± P).23 Meta-analyses of single-agent trastuzumab studies have consistently demonstrated an advantage of adding this agent to neoadjuvant chemotherapy.58 In a pooled analysis of data from two phase III RCTs, Petrelli et al58 reported that adding trastuzumab to anthracycline-taxane chemotherapy resulted in an increase in pCR rates, ranging from 20% to 43% (RR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.41 to 3.03; P = .0002), and a decrease in relapse rate, ranging from 20% to 12% (RR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.94). von Minckwitz et al,60 in a pooled analysis that included trastuzumab in four arms (total of 614 HER2-positive patients), found that the odds of pCR increased 3.2-fold in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer treated with trastuzumab during neoadjuvant chemotherapy (P < .001). There was no association observed, however, between the number of trastuzumab cycles and pCR rates (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.79 to 1.81; P = .39).

Meta-analyses have also revealed that, compared with single-agent anti-HER2 therapy, dual anti-HER2 inhibition significantly increases pCR rates in combination with neoadjuvant chemotherapy.61-66,103 Nagayama et al,64 for example, conducted a network meta-analysis that combined data from ten studies—a total of 2,247 patients in seven different treatment arms—to evaluate the safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer. The anti-HER2 agents studied were lapatinib, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab. These authors found no statistically significant differences among the various dual targeting therapy arms; but, compared with other treatment arms, patients in dual targeting arms had a statistically significantly higher pCR rate (OR, 2.29; 95% credibility interval = 1.02 to 5.02; P = .02). Nagayama et al64 concluded that, for HER2-positive breast cancer treated in the neoadjuvant setting, dual targeting with anti-HER2 agents plus chemotherapy demonstrated a statistically significantly greater number of patients with pCR than chemotherapy alone, single anti-HER2 targeting with chemotherapy, or dual targeting without chemotherapy. In an updated analysis of this network meta-analysis that combined data from 13 studies (total of 3,160 patients in seven different treatment arms), Nakashoji et al61 confirmed that, in the neoadjuvant setting, the combination of two anti-HER2 agents and chemotherapy is most effective against HER2-positive breast cancer. More recently, Chen et al103 evaluated the efficacy and safety of trastuzumab plus pertuzumab vs. trastuzumab alone added to chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant treatment of operable HER2-positive breast cancer. The authors identified 26 studies (a total of 9,872 patients) published between 2005 to 2018. The combination of trastuzumab and pertuzumab was found to significantly improve pCR (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.63; P = .006).

The individual RCTs identified by the literature search conducted for the guideline were, with a few exceptions, included in one or more of the meta-analyses reviewed and are not further summarized here (see corresponding evidence summary tables in Table 1, Data Supplement). As mentioned previously, considered together, data from these trials support either the use of an anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimen plus trastuzumab, or the use of a nonanthracycline chemotherapy and trastuzumab9,18-21,24,28,32,36 in patients with node-positive or high-risk node-negative, HER2-positive disease. The Expert Panel further recognizes that the addition of pertuzumab to these regimens is an option (ACTH ± P or TCH ± P). This is based on data from NeoSphere, a randomized phase II trial of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab,22,23 and the subsequent accelerated (now full) FDA approval in the neoadjuvant setting. Although the addition of pertuzumab resulted in an increase in pCR, it should be noted that the confirmatory APHINITY trial in adjuvant setting resulted in a small improvement in invasive DFS in the overall study population. The effect was most pronounced in the lymph node-positive population, in whom there was a 4.5% improvement in invasive DFS with the addition of pertuzumab.104

The randomized, open-label phase II NeoSphere trial compared trastuzumab plus docetaxel (group A, n = 107) versus pertuzumab and trastuzumab plus docetaxel (group B, n = 107) versus pertuzumab and trastuzumab (group C, n = 107) versus pertuzumab plus docetaxel (group D, n = 96) administered for 12 weeks followed by an anthracycline plus trastuzumab-based regimen in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer in the neoadjuvant setting.22 pCR in the breast was the primary trial end point. Results indicated that patients who received pertuzumab and trastuzumab plus docetaxel had a significantly improved pCR rate (49 of 107 patients; 45.8% [95% CI, 36.1 to 55.7]) compared with patients who received trastuzumab plus docetaxel (31 of 107; 29.0% [20.6 to 38.5]; P = .0141). Febrile neutropenia and leukopenia were the most common grade 3 or higher adverse events. Groups A, B, and D had about the same proportion of serious adverse events (10%-17% of patients); group C, those who did not initially receive cytotoxic therapy, had the lowest pCR rates and a lower proportion of serious adverse events (4% of patients). In a subsequent publication, Gianni et al23 reported NeoSphere 5-year progression-free survival (PFS), DFS, and safety results. The PFS and DFS findings were presented for descriptive purposes only because the trial was not powered to detect survival outcomes differences. Analyses of PFS and DFS revealed no statically significant differences in these long-term outcomes associated with adding pertuzumab to trastuzumab and docetaxel. The safety profile observed in the 5-year analysis of NeoSphere data was consistent with that of the primary analysis.

The randomized, multicenter, open-label, phase III KRISTINE trial compared the potentially less toxic regimen of T-DM1 plus pertuzumab with docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab plus pertuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting.29 This study found that significantly more patients who received the chemotherapy-containing regimen (TCH-P) achieved a pCR than patients who received T-DM1 plus pertuzumab (55.7% v 44.4%; P = .016). The T-DM1 plus pertuzumab arm was associated with fewer grade 3-4 adverse events and fewer serious adverse events, as well as with longer maintenance of patient-reported health-related quality of life and physical function. Because of the lower pCR rate, the Expert Panel does not recommend the use of the neoadjuvant T-DM1 plus pertuzumab in patients with node-positive or high-risk node-negative, HER2-positive disease.

Literature review and analysis.

Neoadjuvant therapy and patients with T1a N0 and T1b N0, HER2-positive breast cancer. Patients with T1a and T1b tumors have not been included in trials of neoadjuvant therapy, and therefore there are no data on whether these patients benefit from neoadjuvant treatment. The recommendation against the use of neoadjuvant therapy in these patients represents, in part, the best clinical opinion of the Expert Panel based on personal experience in breast cancer management, which indicates little potential for additional clinical benefit from neoadjuvant versus adjuvant treatment in this group, and concern about overtreatment. The concern about overtreatment is based on results from the multicenter phase II Adjuvant Paclitaxel and Trastuzumab (APT) trial that administered weekly paclitaxel and trastuzumab for 12 weeks, followed by 9 months of trastuzumab, to 406 patients with node-negative (98.5%), HER2-positive breast cancer, 49.5% of whom had T1mic (2.2%), T1a (16.7%), or T1b (30.5%) tumors.105 At 3 years, analyses showed a risk of early disease recurrence of < 2%; the survival free from invasive disease was 98.7% (95% CI, 97.6 to 99.8). Longer-term results of the APT trial were published in 2019.106 The 7-year breast cancer-specific survival was 98.6% (95% CI, 97.0 to 100).

There is uncertainty with regard to patients with T1c N0 disease, as these patients were included in both the APT de-escalation trial and the KATHERINE trial.9,105,106 Depending on the clinical circumstances, these patients could be considered for neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The advantage is that there may be additional benefit from T-DM1 if patients do not have a pCR9; however, there is a risk of overtreatment based on the results of APT.105,106

Clinical interpretation.

Independent of the cytotoxic chemotherapy backbone, the addition of trastuzumab alone to neoadjuvant chemotherapy increases pCR rates 2- to 3-fold and is the foundation of HER2-directed therapy. The addition of a second HER2-targeted therapy further increases rates of pCR, but the absolute benefit is varied, with patients who have HR-negative disease and node-positive disease appearing to benefit most. Treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer epitomizes the goal of tailored therapy with escalation and de-escalation strategies. HER2-targeted therapy combined with chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting, followed by adjuvant T-DM1 if residual disease is found, illustrates appropriate escalation for high-risk disease. By contrast, utilization of the APT regimen in the adjuvant setting for stage I disease demonstrates currently implemented de-escalation. Ongoing studies will continue to clarify additional de-escalation approaches in the neoadjuvant setting.

FUTURE RESEARCH

Most neoadjuvant clinical trials use pCR as the primary end point. A plethora of data has shown that patients who have a pCR have an excellent prognosis. However, as several trials have demonstrated, improvements in pCR rate in the neoadjuvant setting do not always translate into large differences in breast cancer outcomes, thus promising therapies need long-term confirmatory data. It is not feasible to test all new treatment strategies in the adjuvant setting, as each trial takes thousands of patients and many years of follow-up. Trials in the neoadjuvant setting, such as the I-SPY2 trial and studies of CDK4/6 inhibitors in combination with endocrine therapy, may serve to identify the most promising treatment approaches to bring forward into adjuvant trials.107-111 Additionally, it is clear that patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy have a worse outcome. This population serves as an ideal group in whom new therapies or treatment escalation strategies should be studied. Numerous trials will inform a more personalized approach to both escalation and de-escalation using neoadjuvant therapy response.

PATIENT AND CLINICIAN COMMUNICATION

For recommendations and strategies to optimize patient-clinician communication, see Patient-Clinician Communication: ASCO Consensus Guideline.112 Communication topics of particular relevance to neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer include the need to (a) clarify the goals of treatment so that the patient understands likely outcomes and can relate the goals of treatment to their goals of care (eg, downstaging to enable BCS and desire for immediate surgery); and (b) ensure the patient's understanding of the potential benefits and burdens of any proposed treatment. Communicating the goals of treatment with patients in the neoadjuvant setting can be challenging. Patients for whom neoadjuvant treatment is proposed begin treatment very quickly after diagnosis, which leaves very little time to ask questions about the therapy they are about to receive. Many patients feel like they do not receive adequate information to make decisions or manage the side effects of neoadjuvant therapy.113

Clinicians should make sure patients understand why neoadjuvant therapy is being offered. The goals of treatment—for example, increasing operability, allowing time for genetic test results, or individualizing adjuvant treatment—should be clearly communicated. Informing patients about the rationale for neoadjuvant therapy and its benefits can help decrease anxiety since patients may perceive receiving neoadjuvant therapy as a delay in necessary surgery.

Many patients and their friends and family may not understand the benefit and necessity for neoadjuvant therapy without an explanation of the difference between local therapy (surgery) and systemic therapy (chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and targeted therapy). For example, it is much easier for patients to understand that removing the cancer from the breast will eliminate the threat of it spreading. Some patients may feel that leaving the cancer in the breast while receiving neoadjuvant therapy is unsettling.113 It is important to explain that systemic therapy not only treats the tumor in the breast but also treats any tumor cells that may have spread out of the breast (subclinical). In addition, it is helpful to inform patients about clinical trials that have shown that it does not matter if chemotherapy is given before or after surgery.

Although one of the benefits of neoadjuvant therapy is seeing one's cancer respond to the therapy, there remains the possibility that the tumor does not shrink during neoadjuvant therapy. Therefore, it is important to inform patients how the tumor is monitored during neoadjuvant therapy and what will happen if the tumor does not respond or grows during therapy. Choosing a method and frequency for monitoring tumor shrinkage or growth should be a decision agreed upon by both clinicians and patients to decrease anxiety for the patients. In addition, clinicians should talk to patients about the side effects that they may experience during neoadjuvant therapy early during treatment and allow time for questions. This is particularly challenging in patients who receive therapy soon after their initial diagnosis, as there is not a lot of time to process information before therapy begins. Many patients can feel unprepared, since they go from being healthy to being very ill from therapy in a short period of time.113 The emotional support and management of treatment follows a different timeline and path during neoadjuvant therapy compared with the much more commonly used adjuvant therapy, which can leave patients feeling unprepared and unsupported.

A recommendation for neoadjuvant therapy ideally involves a multidisciplinary team, including medical oncology, surgery, radiology, and radiation oncology. Unfortunately, not all patients have ready access to a multidisciplinary setting. It is therefore crucial for the clinicians and healthcare system to promote multidisciplinary treatment of patients with breast cancer. As breast cancer treatment becomes more personalized, more patients may be able to benefit from neoadjuvant therapy.

When clinicians are talking with their patients about neoadjuvant therapy, they should use plain language to describe complicated terms; say, for example, “therapy before surgery” instead of “neoadjuvant therapy,” and say “therapy after surgery” instead of “adjuvant therapy.” Also, when talking about the purpose to de-escalate or escalate therapy based upon their tumor's response to neoadjuvant therapy, use the term “optimizing therapy,” to determine whether they will need additional therapy or usual care. Since there is still a lot to learn about how to optimize treatments for patients with breast cancer who receive neoadjuvant therapy, patients should be asked to participate in clinical trials when available.

HEALTH DISPARITIES

Although ASCO clinical practice guidelines represent expert recommendations on the best practices in disease management to provide the highest level of cancer care, it is important to note that many patients continue to have limited access to medical care. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care contribute significantly to this problem in the United States. Patients with cancer who are members of racial or ethnic minorities suffer disproportionately from comorbidities, experience more substantial obstacles to receiving care, are more likely to be uninsured, and are at greater risk of receiving care of poor quality than other Americans. Many other patients lack access to care because of their geographic location and distance from appropriate treatment facilities. Awareness of these disparities in access to care should be considered in the context of this clinical practice guideline, and healthcare providers should strive to deliver the highest level of cancer care to these vulnerable populations.114