Abstract.

Scabies, impetigo, and other skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) are highly prevalent in many tropical, low-middle income settings, but information regarding their burden of disease is scarce. We conducted surveillance of presentations of scabies and SSTIs, including impetigo, abscesses, cellulitis, and severe SSTI, to primary health facilities in Fiji. We established a monthly reporting system over the course of 50 weeks (July 2018–June 2019) for scabies and SSTIs at all 42 public primary health facilities in the Northern Division of Fiji (population, ≈131,914). For each case, information was collected regarding demographics, diagnosis, and treatment. There were 13,736 individual primary healthcare presentations with scabies, SSTI, or both (108.3 presentations per 1000 person-years; 95% confidence interval [CI], 106.6–110 presentations). The incidence was higher for males than for females (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.15; 95% CI, 1.11–1.19). Children younger than 5 years had the highest incidence among all age groups (339.1 per 1000 person-years). The incidence was higher among the iTaukei (indigenous) population (159.9 per 1000 person-years) compared with Fijians of Indian descent (30.1 per 1000 person-years; IRR, 5.32; 95% CI, 5.03–5.61). Abscess was the condition with the highest incidence (63.5 per 1,000 person-years), followed by scabies (28.7 per 1,000 person-years) and impetigo (21.6 per 1,000 person-years). Scabies and SSTIs impose a substantial burden in Fiji and represent a high incidence of primary health presentations in this population. The incidence in low-middle income settings is up to 10-times higher than that in high-income settings. New public health strategies and further research are needed to address these conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) are a common reason for healthcare presentations in many countries.1–4 They range from relatively benign conditions, such as impetigo, uncomplicated cellulitis, and small abscesses, to more serious diseases, including pyomyositis and necrotizing fasciitis, which can progress to life-threatening systemic infections.3 Scabies, which is caused by infestation with the mite Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis, is a common predisposing condition to bacterial SSTI in endemic populations.5,6

Secondary bacterial skin infections as a result of scabies (most often in the form of impetigo) occur when breaches of skin caused by scratching allow bacteria, mainly Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus, to penetrate the epidermis.7–9 In addition, S. scabiei secrete serine protease inhibitors that inhibit host innate immunity, thereby promoting bacterial proliferation.10

Scabies and impetigo are highly prevalent in tropical and low-middle income settings, with estimated global prevalence of 204 million and 162 million people, respectively.11,12 The community prevalence of scabies in the Pacific region, which is the setting evaluated in this study, has been reported to be between 32 and 71%.13 Similarly, impetigo has a high prevalence (20–43%) in the Pacific.5,13

Although the community prevalence of scabies and impetigo have been estimated in some tropical and low-middle income settings,5,12,14 there are few data regarding the incidence of other SSTIs, such as abscess and cellulitis, or the primary healthcare utilization for these conditions in these populations.15 Studies performed in high-income countries have shown that the majority of healthcare presentations for SSTIs are to primary healthcare.1 In addition, SSTIs form a large proportion of primary healthcare presentations, for example, impetigo accounted for 12% of clinic presentations by Australian Aboriginal children; impetigo was the third most common infectious disease presentation after upper respiratory tract and ear infections.16 The overall annual incidence of SSTI presentations to primary healthcare in remote Aboriginal communities in Australia in 2014 was as high as 700 presentations per 1,000 population.17

An improved understanding of the burden of scabies and SSTIs in low-middle income populations, including at the primary healthcare level, is needed to inform clinical management and public health control strategies of these diseases and help prioritize further research. This study aimed to describe the incidence, demographic distribution, and management of primary healthcare presentations of scabies and SSTIs in Fiji.

METHODS

Setting.

This study was conducted in the Northern Division of Fiji (population, 131,914 in 2017),18 one of four primary administrative units of the country. Fiji’s Northern Division comprises the country’s second and third largest islands (Vanua Levu and Taveuni). Approximately 55% of the population in the Northern Division are iTaukei (indigenous). The Northern Division is further divided into four administrative subdivisions: Macuata, Cakaudrove, Bua, and Taveuni. Macuata subdivision has the highest urban population (41.2% compared with 29.4% for the division overall)18 and contains the division’s capital, Labasa. A national survey of scabies conducted in 2007 found that the Northern Division had the highest prevalence of scabies (28.5%) and impetigo (23.7%) in Fiji.5 Fiji has a tropical climate, with a warm, wet season from November to April, and a cool, dry season from May to October.19

Primary health structure.

There are 42 public primary healthcare facilities that service the whole Northern Division population (Figure 1); these comprise the divisional hospital, 18 health centers (3 within subdivisional hospitals), and 23 nursing stations. The divisional hospital in Labasa and three subdivisional hospitals provide primary health services via Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) clinics, general outpatient clinics, and emergency departments. IMCI is a World Health Organization (WHO) initiative providing dedicated primary healthcare to children younger than 5 years, including scheduled routine visits for immunizations and growth checks by a trained nurse.20 Health centers are staffed by at least one doctor or nurse practitioner and one or more nurses, and they provide for catchments of 3,500 to 10,000 people. Staffing and capacity vary widely, from two staff members in rural areas to up to 20 staff in towns with larger units, thereby offering allied health services and overnight admissions.21 Health center staff also conduct community outreach throughout the year and annual school visits between January to June to perform evaluations of general health, nutrition, and dental health and administer vaccinations. Nursing stations are staffed by a single registered nurse trained to perform IMCI procedures and able to independently dispense a limited range of medications. They provide health services to catchment populations between 100 and 5000, and they evaluate between 1,500 and 30,000 presentations per year.21,22 There are very few private general practice clinics in the Northern Division (eight practitioners registered in 2011, all confined to urban areas).21 These practices were not included in the surveillance performed during this study.

Figure 1.

Primary healthcare facilities in the Northern Division. The colored lines represent health facilities within the four subdivisions: red = Macuata; blue = Cakaudrove; green = Taveuni; yellow = Bua.

Surveillance.

We established a monthly reporting system at all public healthcare facilities in the Northern Division for presentations of scabies and SSTIs from July 16, 2018 to June 30, 2019. Consultations were performed by clinicians and administrators in the Northern Division public health service. Processes were then piloted in Macuata subdivision during May 2018. Before commencement of the surveillance, standard operating procedures for data collection and reporting flowcharts were distributed to all health facilities. Primary healthcare staff in charge of routine reporting from each facility were trained individually by study personnel regarding the reporting procedures.

Inclusion and classification of diagnoses were adapted from a validated IMCI skin algorithm for common skin conditions in Fiji,20 with diagnostic criteria extended to patients of all ages. Staff at all primary healthcare facilities reported presentations of scabies and the following SSTIs: infected scabies, impetigo, cellulitis, abscess, and severe SSTIs. A severe SSTI was defined according to the IMCI guidelines as an individual presenting with a “general danger sign” (inability to tolerate oral intake, convulsions, or altered levels of consciousness) or with extensive warmth, redness, or swelling of the skin.23 Repeated presentations for the same symptom, follow-up visits, and visits for dressing changes were excluded from the monthly report. Cases diagnosed in general outpatient departments, emergency departments, IMCI clinics, during school visits, and during community outreach were included in our surveillance.

Health facility staff recorded de-identified individual patient data (demographic characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment) on carbon copy forms in a study booklet that was submitted monthly to the study team. Data regarding treatment included prescriptions of antibiotics or permethrin, surgical procedures performed at the health facility, referral to a larger health facility, and admission within the referring health facility. Most facilities transcribed data into the study booklet at the end of the month from their patient registries. However, at larger facilities with greater numbers of presentations, cases were recorded directly in the study booklet daily. At the end of every month, the original reporting sheet was delivered to the study team. Carbon copies were retained at the respective health facilities and at the subdivisional level. Data were entered by the study team into a REDCap database and securely stored in an online server housed at MCRI.24,25

Statistical analysis.

The incidence of new diagnoses was calculated per 1,000 census population per year with 95% binomial exact confidence intervals (CIs). Population subgroups were compared by calculating the incidence rate ratios (IRR) with the 95% CI. Population data including age, sex, and subdivision-specific denominators were obtained from the 2017 Fiji Bureau of Statistics census.18 Because population data by ethnicity were not available from the 2017 census, we applied proportions from the 2007 Northern Division census to the 2017 census population to calculate ethnicity-specific denominators.26 Census population data by health facility catchment area were also not available; therefore, we applied proportions from the health facilities’ own 2019 community profile data to the 2017 census data. Health facilities servicing the same catchment population were grouped into 39 health catchments (Figure 1). Health catchments were classified as urban if at least 50% of their population resided in urban settings. When reporting for the surveillance period was incomplete for a health catchment, we adjusted the annual incidence to account for missed months of reporting. The monthly incidence was calculated per 1,000 population per 30 days. Because school visits only occurred between January to June each year, the monthly incidence was calculated by both including and excluding school visits to more accurately represent seasonality.

During the analysis, presentations recorded as infected scabies were considered presentations with both scabies and impetigo. Patients with a recorded diagnosis of both cellulitis and abscesses were analyzed as abscess only, because we assumed that signs of cellulitis in the presence of abscess were caused by the abscess itself. The maximum mean monthly land surface temperatures for the Northern Division were obtained from the Fiji Meteorological Service through direct correspondence. We used Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for statistical calculations.

Ethical approvals.

The study was performed as part of the Big SHIFT trial investigating the effects of ivermectin-based mass drug administration for the control of scabies and SSTIs (trial ID: ACTRN12618000461291). Ethical approval for Big SHIFT was granted by the Fiji National Health Research Ethics Review Committee (reference number: 2018.38.NOR) and the Royal Children’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee in Melbourne, Australia (reference number: 38020).

RESULTS

Overall incidence.

Of the 39 health catchments, 35 completed reporting for the entire surveillance period, with 41 weeks of missing reporting across the 4 remaining health catchments. Most presentations were to general outpatient clinics (62.5%), followed by IMCI clinics (29.5%). Activities including school visits and community outreach accounted for 4.7% and 2% of cases, respectively (Supplemental Table 1).

During the 50-week surveillance period, a total of 13,736 people presented with scabies and SSTI, equivalent to an all-age incidence of 108.3 presentations per 1,000 person-years (95% CI, 106.58–110). There were 11,312 people who presented with SSTIs only, equivalent to 89.2 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI, 87.6–90.8).

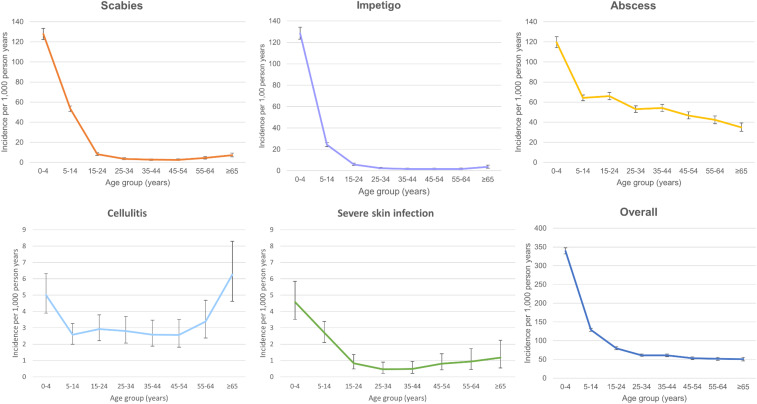

The overall incidence was consistently higher for males (115.1 per 1,000 person-years) than for females (99.9 per 1,000 person-years; IRR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.11–1.19) for all conditions in all age groups (Table 1). The age-specific incidence for all conditions combined was highest among children younger than 5 years (339.1 per 1,000 person-years) and lowest among those older than 64 years (51.0 per 1,000 person-years; IRR, 6.65; 95% CI, 6.00–7.39) (Figure 2, Table 1). Of the 5,191 children younger than 5 years, 1,534 (29.6%) were younger than 1 year and 1,290 (24.9%) were between 1 and 2 years of age. The iTaukei population (159.9 per 1,000 person-years) had a markedly higher incidence than Fijians of Indian descent (30.1 per 1,000 person-years; IRR, 5.32; 95% CI, 5.03–5.61).

Table 1.

Incidence of primary health presentations by sex, ethnicity, and age

| Scabies | Impetigo | Abscess | Cellulitis | Severe SSTI | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | Incidence (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | Incidence (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | Incidence (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | Incidence (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | Incidence (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 29.5 (28.2–30.8) | 1.07 (1–1.14) | 22 (20.9–23.2) | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) | 68.7 (66.7–70.6) | 1.2 (1.14–1.25) | 3.7 (3.2–4.2) | 1.3 (1.06–1.59) | 1.6 (1.3–1.9) | 1.13 (0.84–1.53) | 115.1 (112.7–117.6) | 1.15 (1.11–1.19) |

| Female | 27.6 (26.3–28.9) | ref | 20.9 (19.7–22) | ref | 57.4 (55.6–59.3) | ref | 2.8 (2.4–3.3) | ref | 1.3 (1.1–1.7) | ref | 99.9 (97.6–102.3) | ref |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| iTaukei | 43.8 (42.3–45.4) | 7.55 (6.69–8.55) | 31.6 (30.3–32.9) | 5.41 (4.78–6.13) | 93.5 (91.4–95.7) | 5 (4.69–5.39) | 4.7 (4.2–5.2) | 3.92 (2.97–-5.27) | 2.2 (1.9–2.6) | 6.35 (3.84–11.19) | 159.9 (157.2–162.6) | 5.32 (5–5.61) |

| Other ethnicity | 27.1 (23.5–31.1) | 4.67 (3.87–5.62) | 23.2 (19.9–27.0) | 4 (3.27–4.82) | 62.3 (56.9–68.2) | 3.35 (2.99–3.75) | 2.9 (1.8–4.4) | 2.42 (1.4–4.05) | 1.1 (0.5–2.2) | 3.21 (1.2–7.84) | 107.9 (100.9–115.3) | 3.59 (3.3–3.92) |

| Fijian of Indian descent | 5.80 (5.15–6.51) | ref | 5.8 (5.2–6.6) | ref | 18.6 (17.4–19.8) | ref | 1.2 (0.91–1.54) | ref | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | ref | 30.1 (28.6–31.6) | ref |

| Age, years) | ||||||||||||

| 0–4 | 127.7 (122.2-133.3) | 16.88 (13–22.32) | 128.4 (122.9–134) | 33.95 (23.56–50.84) | 119.5 (114.2–125) | 3.42 (3–3.91) | 5 (3.9–6.3) | 0.82 (0.56–1.21) | 4.5 (3.5–5.8) | 4.32 (2.06–10.43) | 339.1 (331.2–347.1) | 6.65 (6–7.39) |

| 5–14 | 53.8 (51.1–56.6) | 7.11 (5.47–9.41) | 24.5 (22.7–26.4) | 6.48 (4.47–9.75) | 64 (61.1–67) | 1.83 (1.61–2.09) | 2.6 (2–3.3) | 0.42 (0.59–0.62) | 2.4 (1.9–3.1) | 2.33 (1.11–5.62) | 128.8 (124.7–132.9) | 2.53 (2.27–2.81) |

| 15–24 | 8.2 (7.0–9.6) | 1.04 (0.77–1.43) | 6.1 (5–7.3) | 1.54 (1.02–2.4) | 66.2 (62.7–69.8) | 1.82 (1.6–2.09) | 2.9 (2.2–3.8) | 0.46 (0.31–0.69) | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) | 0.72 (0.29–1.97) | 80.0 (76.2–84.0) | 1.51 (1. 35–1.69) |

| 25–34 | 3.7 (2.8–4.7) | 0.47 (0.32–0.68) | 2.5 (1.8–3.3) | 0.63 (0.38–1.04) | 53.2 (49.9–56.7) | 1.47 (1.28–1.69) | 2.7 (2–3.6) | 0.43 (0.28–0.66) | 0.3 (0.1–0.8) | 0.32 (0.09–1.04) | 61.3 (57.8–64.9) | 1.15 (1.03–1.3) |

| 35–44 | 2.8 (2–3.7) | 0.35 (0.22–0.53) | 1.7 (1.1–2.4) | 0.43 (0.25–0.74) | 55 (51.5–58.5) | 1.51 (1.32–1.74) | 2.5 (1.8–3.4) | 0.4 (0.25–0.61) | 0.5 (0.2–1) | 0.44 (0.14–1.35) | 61.7 (58.1–65.4) | 1.16 (1.04–1.31) |

| 45–54 | 2.8 (2–3.8) | 0.36 (0.24–0.55) | 1.7 (1.1–2.5) | 0.43 (0.24–0.79) | 47.8 (44.4–51.4) | 1.32 (1.14–1.52) | 2.5 (1.8–3.4) | 0.39 (0.25–0.62) | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.75 (0.28–2.11) | 54.3 (50.7–58.1) | 1.03 (0.91–1.16) |

| 55–64 | 4.7 (3.5–6.2) | 0.6 (0.4–0.89) | 1.8 (1.1–2.8) | 0.45 (0.24–0.84) | 42.7 (39–46.7) | 1.18 (1–1.37) | 3.3 (2.3–4.6) | 0.52 (0.32–0.82) | 0.8 (0.3–1.5) | 0.69 (0.23–2.12) | 52 (47.9–56.4) | 0.98 (0.86–1.12) |

| ≥ 65 | 7.6 (5.8–9.8) | ref | 3.8 (2.5–5.4) | ref | 34.9 (30.9–39.3) | ref | 6.1 (4.5–8.1) | ref | 1 (0.5–2.1) | ref | 53 (47.95–58.31) | ref |

| Total | 28.7 (27.8–29.7) | 21.6 (20.8–22.4) | 63.5 (62.1–64.8) | 3.3 (3–3.6) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 108.3 (106.6–110.2) | ||||||

Incidence is expressed per 1,000 population per year. IRR = incidence rate ratio; CI = confidence interval. Females, Fijians of Indian descent, and the population 65 years or older were used as reference groups to calculate the IRR. There were 75 entries missing data for sex, 232 entries missing data for ethnicity, and 215 entries missing data for age; these entries were not included in these incidence calculations.

Figure 2.

Age-specific incidence of each condition. Note the different scales on the y-axis between conditions.

Scabies and impetigo.

There were 3,643 presentations of scabies (28.7 per 1,000 person-years) and 2,724 presentations of impetigo (21.6 per 1,000 person-years). Presentations were most common for young children (incidence rates of scabies and impetigo presentations among those younger than 5 years were 127.7 and 128.4 per 1,000 person-years, respectively) (Figure 2, Table 1). Presentations of scabies and impetigo were at least four-times as frequent among the iTaukei population than among Fijians of Indian descent (Table 1). Impetigo was reported in 1,133 of scabies cases, accounting for 31.1% of scabies presentations. There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with scabies with secondary impetigo across age groups (Supplemental Table 2).

Abscess, cellulitis, and severe infection.

There were 8,052 presentations of abscess (63.5 per 1,000 person-years) and 416 presentations of cellulitis (3.0 per 1,000 person-years). The rates of abscess and cellulitis were more evenly distributed across age groups compared with the rates of scabies and impetigo (Figure 2, Table 1). The peak incidence for presentations of abscess was observed in children younger than 5 years (119.5 per 1,000 person-years), and peak incidence for presentations of cellulitis was observed for those older than 64 years (6.1 per 1,000 person-years) (Table 1). Like scabies and impetigo, presentations of abscess and cellulitis were more common among the iTaukei population and people belonging to other ethnicities compared with Fijians of Indian descent (Table 1).

There were 186 presentations classified as severe SSTI, equivalent to an incidence of 1.5 per 1,000 person years. The highest age-specific incidence was observed among children younger than 5 years (39.7 per 1,000 person years; 95% CI, 36.5–43). Eight patients (4.3%) with a severe skin condition also had scabies.

Geographic and seasonal variations.

There was variation in incidence across the four subdivisions and among primary healthcare facilities. Bua subdivision had the highest incidence (155.0 per 1,000 person-years). Macuata subdivision had the lowest incidence (82.9 per 1,000 person-years, Supplemental Table 3). We observed the highest local incidence in remote areas and small islands off the main island of Vanua Levu, including Yadua (639.0 per 1,000 person-years), Kia (426.8 per 1,000 person-years), and Cikobia (291.7 per 1,000 person-years, Supplemental Figure 1). The incidence of primary health presentations was higher for rural populations (123 per 1,000 person-years) than for urban populations (84.3 per 1,000 person-years; IRR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.41–1.51).

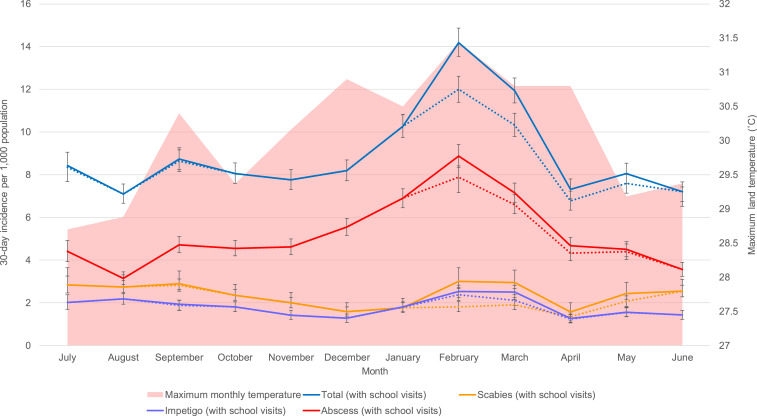

We observed a higher incidence of presentations during the warmer months of November to April (120.6 per 1,000 person-years) compared with the cooler months of May to October (95.9 per 1,000 person-years; IRR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.21–1.3). This observation was attributable to the higher number of presentations of abscess during the warmer period. This increase was still evident after excluding data from school visits (Figure 3). In contrast, the incidence of presentations of scabies was higher between May and October (30.9 per 1,000 person-years) compared with November to April (21.1 per 1,000 person-years; IRR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.36–1.57) when cases detected through school visits were excluded. When we included cases of scabies detected through school visits, there was a second peak in February and March (36.3 per 1,000 person-years). There was no notable pattern in the impetigo incidence throughout the year (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Monthly incidence rates of scabies, impetigo, and abscesses. The area plot illustrates the peak land temperatures for each month. The dotted lines represent the monthly incidence of each condition excluding cases detected from school visits.

Clinical management.

Data regarding management were available for 13,576 of 13,736 presentations. There were 10,020 courses of oral antibiotics, 6,104 intramuscular benzathine penicillin injections, and 3,643 courses of topical permethrin administered. Of 52 patients (0.4%) requiring a surgical procedure at the reporting facility, most (46) were required for treatment of abscesses. A total of 108 patients (0.8%) were admitted to hospital, and 151 (1.1%) were referred to either a health center or hospital for further care.

DISCUSSION

We observed a very high incidence of primary health presentations of scabies and SSTIs in Fiji; the incidence was up to 10-times higher than that observed in high-income countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, and the Netherlands.27–30 Our results suggest that approximately 10% of the population presented over the course of the year of observation with one or more of these conditions. There were especially high rates among children younger than 5 years, the iTaukei population, and remote island communities. Our study highlights the utility of primary healthcare surveillance for scabies and SSTIs in low-middle-income countries and provides a framework for future epidemiological studies and evaluations of control interventions.

Scabies and SSTIs emerged as important pediatric clinical and public health issues during our study, with very high incidence rates observed among young children. Although it is possible that the observed high rates were attributable to the provision of dedicated IMCI services, and therefore higher ascertainment in this group,17 we believe that the high community prevalence of scabies serves as a major precipitant driving the disease burden of SSTIs in children.13 This hypothesis is supported by our findings that scabies and impetigo had highly similar age-specific incidence rates, and that more than 40% of patients with impetigo had concurrent scabies. Similar findings have been observed during previous prevalence studies.5,13,14 Because signs of scabies are similar for children and adults, extending the IMCI diagnostic algorithm to all ages was unlikely to have affected the identification of cases in older age groups.31

Presentations of scabies and SSTIs were markedly higher in the iTaukei population compared with those of Fijians of Indian descent, which was consistent with the epidemiology of scabies and impetigo described by reports of previous community prevalence studies in Fiji.5,8 Higher incidence rates of other infectious diseases and their sequelae, such as pneumonia, invasive infections with Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus, rheumatic fever, and rheumatic heart disease, have also been observed in the iTaukei population.32–35 We found a particularly high incidence among remote island populations compared with more urbanized areas. Many of these remote communities are predominantly iTaukei populations and lack fresh water sources. A trend toward a higher community prevalence of impetigo in rural communities was described by a global systematic review in 2015.12 The higher incidence in remote island populations during our study may have been caused by a higher burden of disease in the community or closer proximity to facilities enabling primary healthcare access, or both. These results identify remote island communities as sites that could be prioritized for public health interventions to address scabies and SSTIs, including ivermectin-based mass drug administration, and possibly measures to improve water, sanitation, and hygiene.36

There were limitations to our study. First, we could not be completely certain about the accuracy of the diagnoses because reports were submitted on a monthly basis by the health facilities; therefore, cases could not be verified by the study team. In addition, healthcare workers may not identify scabies and impetigo in patients presenting with other symptoms because these conditions are frequently normalized in endemic settings.37 Second, our results reflect the minimum burden of scabies and SSTIs in the population because our surveillance included individuals who presented for primary healthcare reasons rather than the disease burden at the community level; although, there was a possibility of duplicate entries of cases for the small proportion of patients referred to other facilities for further care. In addition, we did not collect information regarding presentations to private general practitioners. It is also possible that traditional medicines, which are widely used in Fiji, may be sought by a proportion of patients with scabies and SSTIs; therefore, these individuals may not present to healthcare facilities.38

The major strength of this study was that all 42 public primary healthcare facilities participated in the reporting process and the high rates of compliance over the course of 50 weeks of surveillance. The results we present are a robust representation of presentations at these facilities over this period and a novel insight into the burden of scabies and SSTI in a middle-income setting. General outpatient clinics and IMCI were the predominant reporting sources for all conditions, suggesting that monitoring for the clinical and public health impact of scabies and SSTIs could focus on these two primary healthcare services. School visits detected a substantial (10%) proportion of cases of scabies cases in the population, suggesting that school surveillance could be an additional important method of determining scabies burden. Integration of a surveillance method like ours in routine public health reporting in Fiji, and in other countries where scabies and SSTIs are prevalent, could provide a feasible approach to monitoring the health burden of these conditions, guide research priorities, and evaluate the efficacy of public health interventions, although streamlining of data fields may be warranted to facilitate easier data collection and entry. Additional costs required to implement this surveillance included the time for primary healthcare clinicians to transcribe case data from their registries to the reporting form and the cost of a central coordinator. Fiji has an existing primary health reporting system, and reporting data for scabies and SSTI presentations could be integrated into this existing system, which would minimize any additional costs. Similar primary healthcare surveillance has been successfully implemented for other infectious diseases in both low-middle-income and high-income settings, thereby providing further support for our surveillance approach.39,40

We have shown that presentations at primary health facilities for scabies and SSTIs are a viable and valuable measure of the direct morbidity and health system impact caused by these conditions. Further research is warranted to fully understand the impact of scabies and SSTIs on individuals and communities in endemic areas. Our approach to primary healthcare surveillance provides a model for future epidemiological studies of scabies and SSTIs, and a mechanism to assess the effects of targeted treatment and prevention strategies, including community-level interventions for scabies control.41,42

Supplemental tables

Acknowledgments:

We sincerely acknowledge the contributions of the primary health nurses and physicians of the Northern Division who engaged in the reporting process. We also thank the Subdivisional Nursing Managers, Elenoa Vakatelebole, Ana Tovehi, Vilisi Tuisago Katuba, Mere Tikoibua, and Pulotu Lebaivalu, as well as the Divisional Director or Nursing, Mereseini Kamunaga, for collation of the monthly reports. We sincerely acknowledge the contributions of Avinesh Prasad at the Fiji Bureau of Statistics and Suzanna Vidmar at Murdoch Children’s Research Institute. We acknowledge Ilaitia Nalele and the Fiji Meteorological for supplying the meteorological data used in this study. We also acknowledge the contributions of Prof. Ross Andrews from the Menzies School of Public Health.

Note: Supplemental materials appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller L, Eisenberg D, Liu H, Chang C, Wang Y, Luthra R, Wallace A, Fang C, Singer J, Suaya J, 2015. Incidence of skin and soft tissue infections in ambulatory and inpatient settings, 2005–2010. BMC Infect Dis 15: 362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma JK, Miller R, Murray S, 2000. Chronic urticaria: a Canadian perspective on patterns and practical management strategies. J Cutan Med Surg 4: 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaye KS, Petty LA, Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, 2019. Current epidemiology, etiology, and burden of acute skin infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 68: S193–S199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schofield J, Sherlock J, Lusignan S, 2020. Trends in attendance of patients with skin conditions in English general practice 2006 to 2016: Sentinel Network Database study. Dermatol Nurs (Lond) 19: 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romani L, Koroivueta J, Steer AC, Kama M, Kaldor JM, Wand H, Hamid M, Whitfeld MJ, 2015. Scabies and impetigo prevalence and risk factors in Fiji: a national survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9: e0003452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carapetis JR, Connors C, Yarmirr D, Krause V, Currie BJ, 1997. Success of a scabies control program in an Australian aboriginal community. Pediatr Infect Dis J 16: 494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M, 2005. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis 5: 685–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steer AC, Jenney AW, Kado J, Batzloff MR, La Vincente S, Waqatakirewa L, Mulholland EK, Carapetis JR, 2009. High burden of impetigo and scabies in a tropical country. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3: e467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong SYC, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG, 2015. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 28: 603–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swe PM, Fischer K, 2014. A scabies mite serpin interferes with complement-mediated neutrophil functions and promotes staphylococcal growth. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8: e2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karimkhani C, et al. 2017. Global skin disease morbidity and mortality: an update from the global burden of disease study 2013. JAMA Dermatol 153: 406–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowen AC, Mahé A, Hay RJ, Andrews RM, Steer AC, Tong SYC, Carapetis JR, 2015. The global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PLoS One 10: e0136789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romani L, Steer AC, Whitfeld MJ, Kaldor JM, 2015. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 15: 960–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mason DS, Marks M, Sokana O, Solomon AW, Mabey DC, Romani L, Kaldor J, Steer AC, Engelman D, 2016. The prevalence of scabies and impetigo in the Solomon Islands: a population-based survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10: e0004803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finley CR, Chan DS, Garrison S, Korownyk C, Kolber MR, Campbell S, Eurich DT, Lindblad AJ, Vandermeer B, Allan GM, 2018. What are the most common conditions in primary care? Systematic review. Can Fam Physician 64: 832–840. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendrickx D, Bowen AC, Marsh JA, Carapetis JR, Walker R, 2018. Ascertaining infectious disease burden through primary care clinic attendance among young Aboriginal children living in four remote communities in Western Australia. PLoS One 13: e0203684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas L, Bowen AC, Ly M, Connors C, Andrews R, Tong SYC, 2019. Burden of skin disease in two remote primary healthcare centres in northern and central Australia. Intern Med J 49: 396–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiji Islands Bureau of Statistics , 2018. 2017 Population and Housing Census Release 1. Fiji Bureau of Statistics. Available at: www.statsfiji.gov.fj.

- 19.Fiji Meteorological Service , Australian Bureau of Meteorology, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, 2011. Current and Future Climate of the Fiji Islands. Pacific Climate Change Science Program Partners, Australian Government. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steer AC, Tikoduadua LV, Manalac EM, Colquhoun S, Carapetis JR, Maclennan C, 2009. Validation of an integrated management of childhood illness algorithm for managing common skin conditions in Fiji. Bull World Health Organ 87: 173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization , Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2011. The Fiji Islands Health System Review. Manila, Philippines: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Drug and Therapeutic Committee , 2006. Fiji Essential Medicines Formulary.

- 23.World Health Organization , 2014. IMCI Module 1, General Danger Sings for the Sick Child. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, et al. 2019. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 95: 103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG, 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiji Islands Bureau of Statistics , 2007. 03_Relationship-Ethnicity-and-Religion-by_Province-of-Enumeration_Fiji-2007. Census 2007 General Tables.

- 27.Tun K, Shurko JF, Ryan L, Lee GC, 2018. Age-based health and economic burden of skin and soft tissue infections in the United States, 2000 and 2012. PLoS One 13: e0206893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fritz SA, Shapiro DJ, Hersh AL, 2020. National trends in incidence of purulent skin and soft tissue infections in patients presenting to ambulatory and emergency department settings, 2000–2015. Clin Infect Dis 70: 2715–2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loadsman MEN, Verheij TJM, van der Velden AW, 2019. Impetigo incidence and treatment: a retrospective study of Dutch routine primary care data. Fam Pract 36: 410–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shallcross LJ, Hayward AC, Johnson AM, Petersen I, 2015. Incidence and recurrence of boils and abscesses within the first year: a cohort study in UK primary care. Br J Gen Pract 65: e668–e676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engelman D, et al. 2020. The 2020 international alliance for the control of scabies consensus criteria for the diagnosis of scabies. Br J Dermatol 183: 808–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magree HC, Russell FM, Sa’aga R, Greenwood P, Tikoduadua L, Pryor J, Waqatakirewa L, Carapetis JR, Mulholland EK, 2005. Chest X-ray-confirmed pneumonia in children in Fiji. Bull World Health Organ 83: 427–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jenney A, Holt D, Ritika R, Southwell P, Pravin S, Buadromo E, Carapetis J, Tong S, Steer A, 2014. The clinical and molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus infections in Fiji. BMC Infect Dis 14: 160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steer AC, Jenney A, Kado J, Good MF, Batzloff M, Waqatakirewa L, Mullholland EK, Carapetis JR, 2009. Prospective surveillance of invasive group a streptococcal disease, Fiji, 2005–2007. Emerg Infect Dis 15: 216–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steer AC, Kado J, Jenney AW, Batzloff M, Waqatakirewa L, Mulholland EK, Carapetis JR, 2009. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Fiji: prospective surveillance, 2005–2007. Med J Aust 190: 133–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.May PJ, Tong SYC, Steer AC, Currie BJ, Andrews RM, Carapetis JR, Bowen AC, 2019. Treatment, prevention and public health management of impetigo, scabies, crusted scabies and fungal skin infections in endemic populations: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 24: 280–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeoh DK, Anderson A, Cleland G, Bowen AC, 2017. Are scabies and impetigo “normalised”? A cross-sectional comparative study of hospitalised children in northern Australia assessing clinical recognition and treatment of skin infections. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11: e0005726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization , 2001. Traditional Medicine. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Brunei, Darulssalam: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagenaar BH, Augusto O, Beste J, Toomay SJ, Wickett E, Dunbar N, Bawo L, Wesseh CS, 2018. The 2014–2015 Ebola virus disease outbreak and primary healthcare delivery in Liberia: Time-series analyses for 2010–2016. PLoS Med 15: e1002508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pont SJ, Grijalva CG, Griffin MR, Scott TA, Cooper WO, 2009. National rates of diarrhea-associated ambulatory visits in children. J Pediatr 155: 56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romani L, et al. 2019. Efficacy of mass drug administration with ivermectin for control of scabies and impetigo, with coadministration of azithromycin: a single-arm community intervention trial. Lancet Infect Dis 19: 510–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romani L, et al. 2015. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. N Engl J Med 373: 2305–2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.