Abstract.

Burkina Faso has high prevalence of anemia in pregnancy (hemoglobin < 11 g/dL), despite the implementation of the WHO recommended guidelines. This study aimed to test the effects of personalized support for pregnant women at home on the trend of anemia prevalence in pregnancy. A cluster randomized trial was conducted from January 2015 to August 2016 at Sindou health district in Burkina Faso. Data were collected from 617 women in their first or second trimester of pregnancy, including 440 and 177 women in the intervention and control groups, respectively. The intervention consisted of a monthly home-based visit to the pregnant woman, focusing on nutritional counseling and pregnancy management, alongside an improvement antenatal visit quality. Compared with the prevalence of anemia in pregnancy in the control group [64.0% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 52.1–74.4%)], that of the intervention group was significantly lower from the fifth home visit onward [36.8% (95% CI: 32.1–41.8%)] (P < 0.001). The adjusted difference-in-differences in anemia prevalence between the two groups was –19.8% (95% CI: –30.2% to –9.4%) for women who received more than four home visits (P < 0.001). The corresponding difference in hemoglobin levels was 0.644 g/dL (95% CI: 0.309–0.167; P < 0.001). Personalized support for pregnant women at home, combined with appropriate antenatal care, can significantly reduce anemia prevalence during pregnancy in rural Burkina Faso.

INTRODUCTION

Anemia in pregnancy is a public health problem, particularly in low-income countries. According to the WHO, anemia is defined as a hemoglobin level of < 11 g/dL.1 The prevalence of anemia in pregnancy exceeds 50% in most sub-Saharan African countries, including Burkina Faso,2 and is associated with increased maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality.3 The main causes of anemia in pregnancy in Africa are nutritional deficiencies (especially iron and folic acid), hemorrhages, hemoglobinopathies, malaria, intestinal helminthiasis, and infections (particularly HIV and Helicobacter pylori).3 To reduce the prevalence and consequences of anemia in pregnancy, the WHO and scholarly societies recommend prevention and treatment strategies including 1) fortification of foods with iron and vitamins (in particular folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin C); 2) screening for anemia in pregnancy during prenatal care by hemoglobin level measurement; 3) oral iron and folic acid supplementation for nonanemic pregnant women (hemoglobin level ≥ 11 g/dL); 4) oral iron therapy at the maximum tolerated dose in pregnant women with hemoglobin levels between 8 and 11 g/dL; parenteral iron therapy in pregnant women with a hemoglobin level between 5 and 8 g/dL in the absence of obstetric or systemic complications; 5) hospitalization in a personalized intensive care unit for any pregnant woman with a hemoglobin level < 7 g/dL; 6) screening of anemic pregnant women for obstetric and systemic diseases; and 7) promotion of primary health care, including deworming and the use of insecticide-treated nets (ITN).4 All of these strategies have been found to be effective, primarily through controlled trials, usually randomized only at the individual level. Trials only randomized at the individual level often overestimate the intervention effect because they do not account for the cluster-related mass effect. There are few randomized community-level trials addressing the effectiveness of these strategies, and these generally target isolated strategies, particularly micronutrient supplementation.5,6 Recently published cluster trials on the specific topic of anemia in pregnancy include that conducted by Bharti et al. in India on the effects of directly observed supervision of iron supplementation and by Ampofo et al. in Ghana on the contribution of pregnant women to anemia control.7,8 In the first case, the intervention reduced the prevalence of anemia by more than half, whereas there was no effect on prevalence in the second trial; however, maternal anemia has often been evaluated through numerous cluster intervention studies of malaria control.9,10 In general, these studies do not sufficiently account for the necessary synergy of strategies to prevent anemia in pregnancy. In Burkina Faso, 58% of pregnant women suffer from anemia, according to the last national survey conducted in 2010, representing a severe level of anemia prevalence in pregnancy, although a significant decline has been observed since 1995.1,11,12 This situation is probably due to insufficient application of the recommended strategies, among which iron supplementation and preventive treatment of malaria are the best applied in Burkina Faso, whereas the other strategies are poorly or not applied because of insufficient strategic options, technical platforms, or resources.13 These observations led us to hypothesize that personalized support for pregnant women at home, focusing on nutritional counseling, iron supplementation, prevention of malaria and intestinal parasites, combined with appropriate antenatal care, would reduce the prevalence of anemia in pregnancy. To this end, we conducted a cluster randomized trial that, in addition to individual characteristics, took into account health areas and geographic zones. This trial was based on a combination of community-based primary health care strategies that have been demonstrated to be effective in promoting maternal and perinatal health in previous studies and projects.14 The study objective was to test the effect of personalized support for pregnant women at home, combined with appropriate antenatal care, on the prevalence of anemia and changes in hemoglobin levels during pregnancy. This study is part of a comprehensive research program on strategies to improve the prevention and management of anemia in pregnancy in Burkina Faso.15

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Trial design and setting.

This community-based cluster randomized trial was conducted in the Sindou health district of the Cascades region of Burkina Faso. This district was chosen because of the contrast between its relatively high economic potential at the regional level and the high prevalence of anemia in pregnancy. In 2015, Sindou district had 28 peripheral public health facilities centered on a district hospital. Each health center had an antenatal care unit, in which prevention of anemia in pregnancy was achieved through iron supplementation and intermittent preventive treatment of malaria with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine during antenatal visits. The drugs provided to women at prenatal visits were sufficient for daily iron/folate and monthly sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine doses.

Study participants.

The participants were pregnant women attending antenatal care; their enrollment took place from August 1 to November 30, 2015, and they were followed up from September 2015 to August 2016. The district’s peripheral health facilities were considered as clusters.

Inclusion criteria for pregnant women.

All consenting women in their first or second trimester of pregnancy who were attending antenatal care in the selected health facilities were included in the study. Gestational age at inclusion was reported from the woman’s antenatal visit booklet. Exclusion criteria were nonresidence in the selected health facilities and the lack of consent for home follow-up.

Inclusion criteria for health facilities.

All peripheral health facilities in the district were eligible.

Variables.

The independent variable was hemoglobin level; anemia was defined as a hemoglobin level < 11 g/dL at all stages of pregnancy. The explanatory variables were as follows:

-

1.

The group (intervention or control);

-

2.

the sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant women at the individual level: age, weight, mid–upper arm circumference (MUAC), gestational age, gravidity, marital status, household size, nonhousehold employment, ethnicity, religion, education; and

-

3.

and at the cluster level: population, coverage of schools, and water infrastructure.

Quantitative variables were age (years), MUAC (centimeters), weight (kilograms), gestational age (months), gravidity (number of pregnancies), and household size (number of persons). Gestational age was that at inclusion in the study, classified as first or second trimester. Nonhousehold employment had two modalities: “yes” for women who had an income-generating activity and “no” for those who did not. Education level included the categories “not in school” for women who had not received formal school education, “primary” for those who had received only elementary education, and “secondary and higher” for women who had attended junior high school, high school, or university. Ethnicity had two categories: “indigenous” for women of common descent with the original occupants of the locality (Senoufo, Goin, Karaboro, Dioula, Turka, and affiliates) and “allogenic” for those of different origins (Mossi, Lobi-Dagara, Daffin, Samogho, Fulani, Bobo, etc.). Religion had two categories: “Muslim” and “other,” the latter of which included Catholic, Protestant, and traditional religions. The matrimonial regimen was either “monogamy” for households with one or two parents or “polygamy” for households with co-wives.

Data collection.

Data were collected from pregnant women using a standardized questionnaire, with measurements for hemoglobin, weight, and MUAC, and by interview or documentation for the other variables. Because of the participants’ low educational level, interviews were conducted orally in the local language. Hemoglobin levels were measured using the Hemocue Hb 301 System.16 Weight was determined using a portable medical scale, with an accuracy of 0.1 kg, and MUAC was determined using a brachial tape, graduated to the nearest millimeter (Shakir tape). The questionnaire was validated by specialists in public health, epidemiology, and biostatistics from the Université libre de Bruxelles in Belgium and the Université Nazi Boni of Bobo-Dioulasso in Burkina Faso. Six female community health workers (CHWs), trained for 1 month, conducted recruitment and follow-up at home interactions, during which the data were collected. Accounting for differences in workload, four CHWs were assigned to the intervention zone and two CHWs to the control zone. Each CHW received data collection tools, measurement equipment, and an interview guide. The CHWs were supervised once a week by the field supervisor and once a month by the research team.

Bias management.

To reduce bias due to language barriers, the questionnaire was translated into Dioula, the main local language in the Sindou district. A pretest of the questionnaire was carried out in the neighboring Hauts-Bassins region before the survey began. Questions were clarified with the CHWs to harmonize their understanding. A meeting was held with the CHWs at the end of the first week of data collection, then once a month to assess and correct the completion of the tools. Hemoglobinometers and scales were checked once a week. Groups, clusters, CHWs, and enrolled pregnant women were coded to avoid misclassification. The age of women was reported from their ID cards and the stage of pregnancy from the health booklet. Gestational age was estimated by antenatal care providers from the first date of the last menstrual period, compared with fundal height measurement. Collected data were subject to weekly quality control, carried out visually by the field supervisor. To minimize selection bias, additional visits were made to nonconsenting women to obtain their consent. The separation of the intervention and control groups into distinct geographic areas and clusters made it possible to avoid contamination between groups and to capture the mass effects of the clusters (health facilities) on the trend of hemoglobin levels. The two zones (intervention and control) were at least 50 km apart, and there was limited contact between participants in the two groups. Data were entered in duplicate to reduce errors.

Sample size.

Sample size determination accounted for the expected difference in prevalence between the two groups over the entire follow-up period. The prevalence of anemia of 58%, observed during the 2010 DHS-MICS IV study in Burkina Faso among pregnant women, was chosen as the assumed prevalence in the control group. On the basis of a study by Bharti et al., a 50% reduction in this prevalence was chosen for detection, with a significance threshold of 5% and a power of 80% (bilateral test).7,11 The intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) in the Bharti study was 0.0274 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.00–0.056); hence, a conservative measure of 0.05 was selected that, according to some authors, represents a high ICC value for cluster randomized trials.17

The number of clusters (C) required in each group, with an estimated average number of women per cluster of m = 40 subjects, was thus calculated using the following formula18:

This sample of four clusters of 40 women in each group would allow detection of a difference in mean hemoglobin levels between the two groups of 0.81 g/dL, with a threshold of 5% and a power of 80% (bilateral test), based on a standard deviation of hemoglobin of 1.5 g/dL, as observed in the Sindou study conducted in Burkina Faso in 2012 (unpublished data). This difference is similar to that observed by Bharti et al.7

Randomization of clusters and allocation concealment.

On the basis of the health map, the Sindou district was divided into two distinct geographic zones, East and West, each comprising half of the 28 peripheral health facilities. Using a random number table generated in Excel software, a data manager, who was not member of the research team, randomly allocated one zone for the intervention arm and the other for the control arm, and then randomly selected four health facilities per zone as clusters for the study. At the end of the 3-month enrollment period, the sample size was reached in the intervention group but not in the control group. A 1-month extension was then made to complete enrolment. To harmonize the enrollment period in the two groups, two additional clusters were randomly selected and included in the intervention group. This modification of the sampling allowed the sample size to be achieved but with a higher number of participants in the intervention group than in the control group. Enrollment in the study was proposed to all eligible pregnant women attending antenatal visits during the recruitment period in the selected health facilities. The intervention was concealed to health workers, pregnant women, CHWs, and field supervisors but not to researchers.

Implementation.

Inclusion.

The authorities provided written consent for the inclusion of all health facilities in Sindou district in the study. The inclusion of pregnant women was preceded by written consent and evidenced by fingerprinting of the women and their spouses (for married women). During the inclusion visit, the woman/couple received the necessary information related to the study; she also received an information sheet detailing the conditions of the study and the addresses of the research team. The community health workers mobilized for home follow-up were sensitive to good attitudes, respect for privacy, rights, and local customs. Inclusion visits were made to the women’s homes.

Intervention group.

At the cluster level, the health team received 2 days of training on nutrition and counseling for pregnant women, focusing on vitamins and iron-rich foods, as well as the prevention and management of anemia in pregnancy. The application of these was evaluated and corrected as necessary during monthly supervision visits by the research team. Each health facility in the intervention group received support from the research project to secure stocks of iron and folic acid for supplementation, albendazole for routine deworming, and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy.

At the individual level, the pregnant woman received a monthly home visit by the CHWs; the intervention package offered by the CHW during the home visit consisted of personalized support, focusing on nutrition (intake of vitamins and iron-rich food, food diversification, and hygiene), iron and folic acid supplementation, use of an ITN, preventive treatment of malaria, deworming, and pregnancy hygiene. Monitoring and correction of adherence to preventive treatment and iron/folic acid supplementation was integrated to this home visit package. In each household, the spouse and other persons who could support the pregnant woman, particularly for treatment adherence and nutrition, were involved in the counseling session. An improvement plan that took into account the level of knowledge and feeding practices was agreed between the woman, her husband, and the community health worker. This level of knowledge was assessed based on 24-h diet recall, frequency of food consumption, and the woman’s knowledge of the definition, causes, consequences, and prevention measures for anemia. The plan also took into account the availability of local food. At the first visit, the CHW provided essential information on anemia, diet in pregnancy, and the needs of the woman for support from her spouse during pregnancy. At the end of each visit, actions to improve nutrition, prevent disease, and pregnancy follow-up measures were agreed upon by the woman, the spouse, and the CHW. From the second visit onward, each visit began with an assessment of previously agreed actions, achievements, nutrition challenges, morbidity, and pregnancy follow-up. Any case of severe anemia detected during the home visit by hemoglobin testing was referred or accompanied to the health facility to which the village was assigned.

During prenatal visits, each woman received individual counseling, iron and folic acid supplementation, preventive treatment of malaria, deworming, nutrition education, and an ITN for those who did not have one.

Control group.

At the cluster level, the health team did not benefit from the training carried out in the intervention group. There was no support to secure stocks of drugs for supplementation and preventive treatments. The health team continued to provide antenatal care, according to the national program without supervision by the research team.

At the individual level, unlike women in the intervention group, women in the control group did not benefit from the home intervention package offered in the intervention group. Monthly data were collected, preferably in the health facilities, just after the antenatal visit and, failing that, at home for the months when the woman did not attend the health facility. The results of hemoglobin tests were transmitted to the health workers. Any case of severe anemia detected at home through hemoglobin testing was referred or accompanied to the health facility.

The training of the control group CHWs, unlike that of the intervention group, was limited to the use of data collection tools and instruments for the control group. It did not include skills for the personalized accompaniment of the pregnant woman.

In both groups.

Follow-up ended at the immediate postpartum visit (within the 6 days after delivery) or in cases of abortion, death, or permanent absence of the woman, and in cases of voluntary withdrawal. For specific reasons (e.g., the woman’s health status, need for additional information or action) that required more than one visit in a month, visits were labeled “additional.” For the months when, because of a woman’s absence or the inability of the CHWs, the home visit did not take place, it was qualified as a “missed visit.”

Household financial participation.

All expenses related to the study (hemoglobin tests, drugs, and other) were covered by the research team. No additional prenatal visits were requested from the women. In the health facilities, they continued to receive the usual benefits and subsidies, in addition to those provided by the study (hemoglobin testing and medication).

Statistical analysis.

After data cleaning, a flow chart of participants was constructed, including the numbers of geographic areas, clusters, and participants at the randomization; inclusion; and follow-up stages.

Check on the validity of randomization.

Validity of randomization was checked by comparing the characteristics of pregnant women and health areas between the two groups before the intervention began. Frequencies (n and %) for categorical variables, means with SD or medians with percentiles 25 and 75 (P25–P75) for quantitative variables are used to describe the two groups. Quantitative variables were compared using the t test and categorical variables using the χ2 test. The P values of the tests were corrected for clusters.19 Clusters characteristics are presented as means with the minimum and maximum (min–max).

Analysis of the fidelity of the implementation and adherence to the intervention.

Analysis of the fidelity of the implementation and adherence to the intervention was performed to assess the performance of CHWs and the adherence of couples to the intervention, based on a sample of women whose follow-up was not interrupted before delivery; follow-up was considered “interrupted” in cases of abortion or loss to follow-up. Fidelity was assessed according to the ratio of the number of planned and achieved home visits, and the number of home visits expected in both groups. The number of expected visits, at the rate of one visit per month, was estimated in number of months, from the theoretical difference between the expected period of delivery and the gestational age at inclusion. Adherence was assessed based on the application of the preventive measures recommended during prenatal visits by pregnant women, as well as the commitments (support promised by the spouse, avoidance of chores, dietary diversification, environmental hygiene, etc.) made at the end of each home visit in the intervention group. For each member of a couple, each commitment made during a visit was recorded and evaluated at the next visit. Adherence to iron and folic acid supplementation and use of the ITN were confirmed by iron/folic acid pill counts and self-reports by women, and their numbers related to the number of visits received, without additional visits. The commitments of the woman and her spouse were related to the total number of visits received.

Evaluation of the effect of the intervention.

Changes in the prevalence of anemia and mean hemoglobin level are presented for each group with 95% CI, based on the number of home visits. To quantify the change in mean hemoglobin level and anemia prevalence during pregnancy over time, a difference-in-differences analysis was performed per follow-up visit, using the inclusion values as references [per group, for each visit: difference-visit = (value-visit – value-inclusion) and then for each visit, difference-in-differences = (difference-visit-intervention – difference-visit-control)]. The analysis of differences was performed using mixed models, with three levels (cluster, female, and measure). Analyses were repeated in the group of women included in the first trimester and in the group of women included in the second trimester. To better highlight the effect of the intervention, number of visits was dichotomized into < 4 versus ≥ 4; interactions between this dichotomous variable and the treatment group were tested in mixed models of anemia and hemoglobin. In these same models and in each group, interactions between the number of dichotomized visits and gestational age at inclusion were also tested to highlight possible differences in the evolution of anemia prevalence and mean hemoglobin levels between the two gestational age groups. ICCs for anemia and hemoglobin were determined from mixed models, accounting for all visits. Analyses were performed using IBM-SPSS Statistics 24 and STATA SE 16.1 software.

Ethics.

The study was conducted in accordance with the terms of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving the participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Center Muraz (Ref. 022-2014/CE-CM, 22-10-2014) in Bobo-Dioulasso,20 Burkina Faso. The study has also been approved by the health authorities. Informed and written consent was obtained from all participants. Pregnant women suffering from anemia (hemoglobin level < 11 g/dL) were referred and/or accompanied to their referring health facility. The study did not involve any major risks to the integrity and rights of the participants.

RESULTS

Participants.

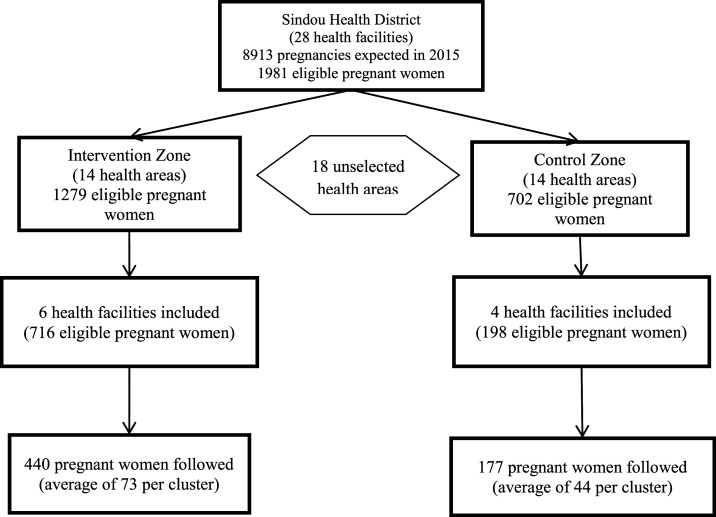

Ten health areas (clusters) were included in the study, including six areas in the intervention zone and four in the control zone. Of an estimated total of 914 eligible pregnant women, 617 were enrolled and included in the analysis, including 440 in the intervention group and 177 in the control group; the average number of women was 62 per cluster. Two women in the intervention group and four in the control group were lost to follow-up but were included in the analysis because they all received at least one follow-up home visit; this represents 0.97% of the sample (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study participants.

Baseline characteristics of pregnant women and clusters in the two groups.

As shown in Table 1, women in the two groups differed significantly only in their distribution by religion. The intervention group had more Muslim women than the control group. There was a trend (P = 0.06) to larger household size in the control group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of pregnant women in the intervention and control groups

| Characteristic | Intervention, n (%) | Control, n (%) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of pregnant women | 440 | 177 | – |

| Age (years)† | 25.2 (6.4) | 25.6 (6.4) | 0.25 |

| Mid–upper arm circumference (cm)† | 26.0 (2.3) | 25.6 (2.0) | 0.10 |

| Weight (kg)† | 56.7 (7.7) | 56.0 (6.8) | 0.66 |

| Gestational age | 0.10 | ||

| First trimester | 272 (61.8) | 74 (41.8) | |

| Second trimester | 168 (38.2) | 103 (58.2) | |

| Gravidity‡ | 4 (2–5) | 4 (2–6) | 0.30 |

| Nonhousehold employment | 0.57 | ||

| Yes | 240 (55.6) | 74 (41.8) | |

| No | 200 (45.4) | 103 (58.2) | |

| Education | 0.09 | ||

| Out of school | 331 (75.6) | 147 (83.1) | |

| Primary | 81 (18.5) | 15 (8.5) | |

| Secondary and higher | 26 (5.9) | 15 (8.5) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.54 | ||

| Aboriginal | 389 (88.4) | 142 (80.2) | |

| Allogenic | 51 (11.6) | 35 (19.8) | |

| Religion | 0.026 | ||

| Muslim | 428 (97.3) | 120 (67.8) | |

| Other | 12 (2.7) | 57 (32.2) | |

| Matrimonial regimen | 0.55 | ||

| Monogamy | 239 (54.4) | 101 (57.1) | |

| Polygamy | 200 (45.6) | 76 (42.9) | |

| Household size (no. of persons)† | 5 (3–8) | 8 (6–13) | 0.06 |

P values corrected for clusters.

Mean (SD).

Median (P25–P75).

Clusters in the control area were less populated and less covered by high schools (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of clusters (health areas) in both groups

| Feature | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|

| No. of clusters, n | 6 | 4 |

| No. of women per cluster | 73.3 (16–154) | 44.3 (21–95) |

| No. of villages and farming hamlets, n | 101 | 26 |

| No. of villages and hamlets per cluster | 16.8 (5–36) | 6.5 (5–10) |

| No. of administrative villages per cluster | 3.3 (1–5) | 3.0 (2–4) |

| Population covered by cluster | 9024 (4389–16896) | 3132 (2160–4141) |

| No. of primary schools per cluster | 7.3 (2–18) | 3.5 (2–6) |

| No. of primary schools per cluster per 10,000 inhabitants | 8.1 (3.5–10.7) | 11.2 (5.5–18.5) |

| No. of secondary schools per cluster | 2.5 (0–9) | 0.8 (0–1) |

| No. of secondary schools per cluster per 10,000 inhabitants | 2.8 (0–5.3) | 2.4 (0–4.6) |

Data are mean (min–max) unless otherwise noted.

Fidelity and adherence to implementation.

Follow-up was continuous for 94.2% of pregnant women and interrupted before delivery in 36 women, 30 of whom had abortions and six who were lost to follow-up. The completion rate for home visits, used to assess CHW fidelity to the intervention protocol, exceeded 90% in both groups. The median number of home visits was five per pregnant woman, with slightly more visits in the intervention group. Almost all women in the intervention group adhered to the protocol, as shown by the rates of adherence to iron and folic acid supplementation, use of ITN, and the proportion of women who made commitments about measures to prevent anemia in pregnancy. The level spouse participation and commitment, although lower, exceeded 70% for each indicator (Table 3).

Table 3.

Fidelity of implementation and adherence to the intervention (for women undergoing continuous follow-up)*

| Component | Intervention (n = 421) | Control (n = 162) |

|---|---|---|

| Fidelity | ||

| No. of home visits | 2397/2427 (98.8) | 799/849 (94.1) |

| Median (min–max) no. of visits per woman | 6 (1–9) | 5 (1–8) |

| No. of missed visits | 182/2427 (7.5) | 85/849 (10.0) |

| No. of additional visits | 152/2397 (6.3) | 35/799 (4.4) |

| Adherence | ||

| Continuous supplementation in IFA | 2171/2245 (96.7) | 717/764 (93.8) |

| Continued use of ITN | 2185/2245 (97.3) | 680/764 (78.9) |

| Visit in the presence of the spouse | 1934/2397 (80.7) | – |

| Commitment made by the woman | 2296/2397 (96.8) | – |

| Spouse commitment | 1357/1934 (70.2) | – |

ITN = insecticide-treated nets.

Observed number on expected or total number of visits and % for each variable, unless otherwise stated.

Iron and folic acid.

Changes in the prevalence of anemia and hemoglobin levels in both groups.

The prevalence of anemia was higher in the control group than in the intervention group from inclusion to the end of follow-up. The difference in the prevalence of anemia between the two groups, increased from 5% at baseline, with increasing number of visits, and became greater from the fourth visit, when there was an 18% difference in prevalence between the two groups. In the intervention group, mean hemoglobin level increased from admission, more significantly from the fourth visit onward, reaching 11.63 g/dL at the seventh visit. In the control group, mean hemoglobin mean level increased slightly to 10.60 g/dL at the seventh visit, and therefore did not reach the normality threshold of 11 g/dL in this group (Table 4). The ICCs for anemia and hemoglobin estimated from the values of all visits were 0.028 (0.010–0.074) and 0.030 (0.011–0.082), respectively.

Table 4.

Prevalence (95% CI) of anemia and mean hemoglobin level (95% CI) at each visit in each group

| Visit | Anemia % (95% CI) | Hemoglobin (g/dL) Mean (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (inclusion) | ||

| Intervention (n = 440) | 64.8 (55.8–72.8) | 10.41 (10.13–10.68) |

| Control (n = 177) | 69.5 (64.3–74.2) | 10.16 (10.00–10.31) |

| 2 | ||

| Intervention (n = 435) | 61.4 (49.3–72.2) | 10.57 (10.28–10.85) |

| Control (n = 172) | 72.1 (69.8–74.2) | 10.20 (10.06–10.35) |

| 3 | ||

| Intervention (n = 428) | 58.2 (50.0–65.9) | 10.56 (10.26–10.85) |

| Control (n = 166) | 68.1 (63.7–72.1) | 10.41 (10.26–10.56) |

| 4 | ||

| Intervention (n = 405) | 52.8 (41.1–64.3) | 10.84 (10.57–11.11) |

| Control (n = 148) | 70.9 (62.7–78.0) | 10.28 (10.13–10.43) |

| 5 | ||

| Intervention (n = 372) | 36.8 (32.1–41.8) | 11.32 (11.14–11.50) |

| Control (n = 114) | 64.0 (52.1–74.4) | 10.38 (10.22–10.54) |

| 6 | ||

| Intervention (n = 246) | 31.7 (19.4–47.3) | 11.40 (11.11–11.69) |

| Control (n = 57) | 61.4 (56.9–65.7) | 10.52 (10.39–10.65) |

| 7 | ||

| Intervention (104) | 24.0 (13.2–39.7) | 11.63 (11.25–12.01) |

| Control (13) | 53.8 (43.0–64.3) | 10.60 (10.37–10.83) |

| 8 | ||

| Intervention (21) | 9.5 (2.0–35.4) | 12.29 (12.04–12.54) |

| Control (5) | 80.0 (61.1–91.1) | 10.58 (9.92–11.24) |

| 9 | ||

| Intervention (3) | 0.0 | 11.77 (10.64–12.90) |

| Control (0) | – | – |

95% CI = 95% confidence interval, corrected for clusters.

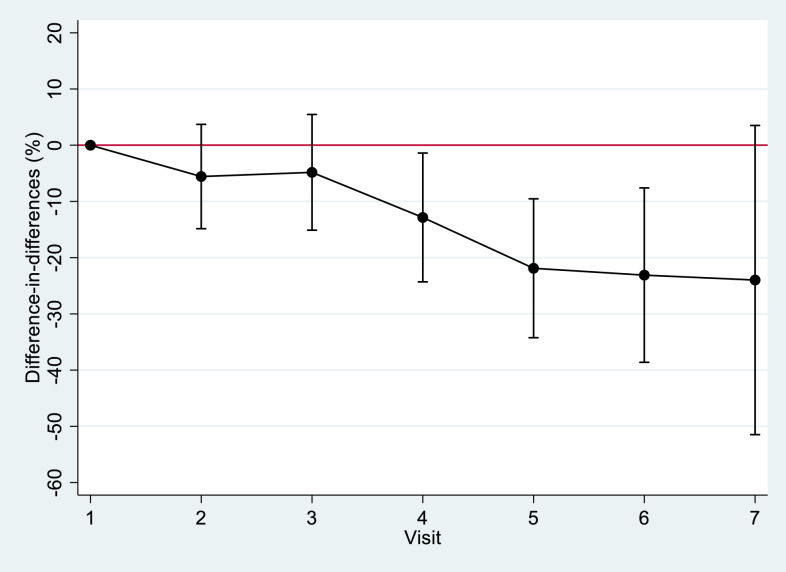

The difference in anemia prevalence between each visit and inclusion became significantly greater between the two groups from the fourth visit onward. At this visit, a decrease in the prevalence of anemia observed in the intervention group was almost 13% greater than that observed in the control group (Figure 2). The same trend was observed for hemoglobin levels, with an increase in mean hemoglobin level from the fourth visit onward in the intervention group, at 0.294 g/dL higher than that observed in the control group. These results were confirmed by the detection of significant interactions (P < 0.001) between the number of visits categorized as < 4 versus ≥ 4 and the treatment group, in mixed models of anemia and hemoglobin. For anemia, the mean differences (95% CI) between the intervention and control groups were –4.5% (–14.4 to 5.4%) and –19.8% (–30.2 to –9.4%) when the number of visits was < 4 and ≥ 4, respectively. For the hemoglobin mean level, the corresponding differences were +0.155 g/dL (–0.127 to 0.437 g/dL) and 0.644 g/dL (0.349 to 0.940 g/dL).

Figure 2.

Evolution of the difference-in-differences in prevalence of anemia in pregnancy between visits and inclusion (in the same group) and between the intervention and control groups. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

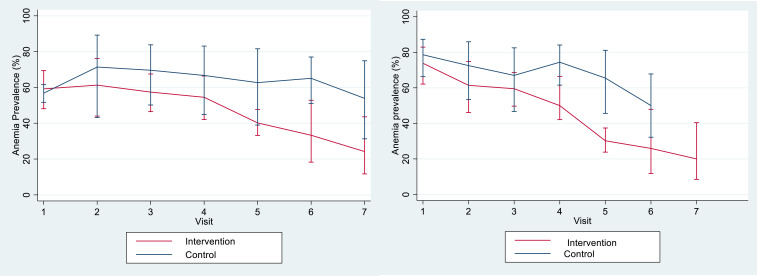

The change in prevalence of anemia in both groups, relative to gestational age at inclusion, is shown in Figure 3. The prevalence of anemia was higher in women included during their second trimester of pregnancy. In these women, in the intervention group, the decrease in prevalence for women with four or more visits was greater than the corresponding decrease observed in women included at their first trimester of pregnancy; the difference in prevalence (95% CI) for women with four or more visits versus fewer than four visits was –25.0% (–31.1 to –19.0%) for women included during their second trimester of pregnancy and –17.2% (–21.4 to –12.9%) for women included during their first trimester (P = 0.036). The change in mean hemoglobin level according to gestational age at inclusion was similar to the change in the prevalence of anemia. Women included during their second trimester of pregnancy had lower mean hemoglobin at inclusion than those included in their first trimester. In the intervention group, there was also a (nonsignificant) greater increase in hemoglobin from the fourth visit onward in women included during their second trimester of pregnancy; the difference in mean hemoglobin level (95% CI) for women with four or more visits versus fewer than four visits was 0.751 (0.591–0.910) for women included during the second trimester and 0.575 (0.463–0.687) for women included in their first trimester (P = 0.077).

Figure 3.

Change in prevalence of anemia (95% confidence interval) relative to gestational age at inclusion (left, first trimester; right, second trimester). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

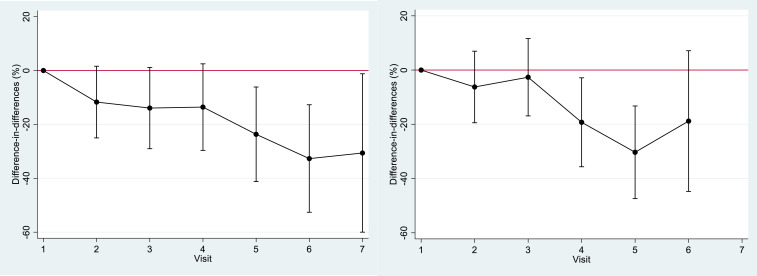

Figure 4 shows differences in anemia prevalence according to gestational age, which indicate the same trends. There was a much greater decrease in the prevalence of anemia in the intervention group than in the control group (23% more decrease in the intervention group) from the fifth visit in women included during their first trimester of pregnancy and from the fourth visit (19% more decrease in the intervention group) in those included in the second trimester. Follow-up ended at delivery and was therefore shorter in women included during their second trimester of pregnancy, among which only five women in the intervention group had seven visits (not shown in the graphs).

Figure 4.

Evolution of the difference-in-differences in anemia prevalence between the two groups according to gestational age at inclusion and visits (in the same group) and between the intervention and control groups (left, first trimester; right, second trimester). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

The evolution of the difference-in-differences in mean hemoglobin levels between the two groups according to gestational age at inclusion and visits also showed a greater improvement in hemoglobin levels in the intervention group by the fourth visit.

DISCUSSION

This study confirmed that personalized support for pregnant women at home, focusing on nutritional counseling, iron supplementation, and prevention of malaria and intestinal parasites, combined with appropriate antenatal care, significantly reduced the prevalence of anemia in pregnancy.

The main limitation of the study was the recruitment of pregnant women by opportunity in health facilities. Consequently, randomization was limited to geographic areas and health facilities but could not be applied to pregnant women. Nevertheless, the results obtained made it possible to verify the initial hypothesis.

Compared with the current threshold hemoglobin level (< 10.5 g/dL) used to define anemia in the second trimester of pregnancy, a threshold of 11 g/dL, that was in use before 2016, led to an overestimation of anemia prevalence in pregnancy.3 This was the main rationale for the apparently smaller reduction in the prevalence of anemia in women included in their first trimester of pregnancy, compared with those recruited during their second trimester in our study.

The satisfactory quality of the data was the result of an effort to control for bias. The implementation of the intervention was also satisfactory, as evidenced by the indicators of CHW compliance and adherence of pregnant women to the study protocol. The extension of the enrollment period to reach the required sample size in the control group was certainly a challenge; however, it was also an advantage in that it resulted in a larger than expected sample size gain in the intervention group. Further, the study had the strength of a negligible proportion of subjects lost to follow-up (< 1%). The use of multilevel mixed models, taking into account adjustments for clustering, repeated measures, and individual characteristics, provided a more realistic estimate of the effect of the intervention. In addition, the separate geographic locations of the two areas of the study reduced the risk of contamination of the control group.

By repeating the hemoglobin test, it was possible to determine the necessary number of home visits at which the reduction in the prevalence of anemia was significant. By the fourth visit to the intervention group, the prevalence of anemia fell below the WHO-estimated 40% severity threshold,1 and the objective of halving the initial prevalence was achieved by the sixth visit. In contrast, the prevalence of anemia remained above 50% until the end of the follow-up in the control group. Evidently, the effect of the intervention increased with the number of home visits, and thus with repetition of the intervention package.

Because of its high prevalence, anemia in pregnancy is a common theme that is regularly addressed by many authors in Africa and elsewhere; however, few results of community-based trials have been published on the specific topic of anemia in pregnancy, and those studies often conclude that there is no effect on the prevalence of anemia.6,8,9 For example, in a study carried out by Ampofo et al. in Ghana in 2018 on the contribution of pregnant women to anemia control, no difference in prevalence was observed at term between the intervention and control groups, due (according to the authors) to the low fidelity of the actors to the implementation of the study protocol. In this study, the intervention occurred only in health facilities, where the counseling that was designed to produce results was offered to pregnant women during a prenatal visit. This did not allow the spouse or other family members to participate in the education sessions8; however, as our results show, support of the pregnant woman by the other members of the family, and especially by the spouse, appears to be essential for adoption of the strategy. In this regard, Nguyen et al. concluded from a cluster trial conducted in 2018 in Bangladesh that spousal support for wives accounted for nearly half of the positive impact of the supplementation and dietary diversification program among pregnant women.21

In a multicenter community-based trial conducted by the Cosmic Consortium in Burkina Faso, the Gambia, and Benin and published in 2019, screening for and treatment of malaria in pregnant women by community health workers had no effect on the course of anemia in pregnancy.9 This intervention included only the community-based malaria screening and treatment strategy, without the other interventions developed in our study.

Trials that resulted in a reduction of the prevalence of anemia in pregnancy have most often focused on supervised iron and folic acid supplementation. A typical example is the study by Bharti et al. in India, published in 2013, where the researchers observed reduction of more than half in the prevalence of anemia at the end of follow-up, which is close to the level of reduction detected in our study.7

Elsewhere, numerous randomized clinical trials on supplementation with iron or other micronutrients have found a reduction in the prevalence of anemia in pregnancy.22–25 In all of these trials, the effect of the intervention was clearly related to direct supervision of treatment. This reinforces the arguments of many authors who recognize that both micronutrient supplementation and food fortification are only short- and medium-term interim solutions to the control of anemia in pregnancy. A comprehensive approach to the control of anemia in pregnancy should, in addition to transitional strategies, move toward sustainable local development strategies26; our trial contributed to this dynamic by opting for building the capacity for the prevention of anemia in pregnancy by the pregnant woman, with the support of her family. The rate of reduction in the prevalence of anemia in the intervention group in the absence of direct supervision was satisfactory and consistent and indicated that the number of home visits could be reduced while maintaining the effectiveness of the intervention; however, as the majority of first antenatal visits in Africa occur beyond the first trimester, the intervention would have been more effective if it had started in the preconception period.27,28

The greatest benefit of our trial is that we tested an entire package of activities for the prevention and management of anemia at all gestational ages at the community level. The home visits and counseling sessions allowed us to adapt the intervention to the local context, particularly in terms of nutrition education based on local foods and mobilizing family support for the pregnant woman. The satisfactory rates of participation and commitment by women, their husbands, and CHWs are evidence of the acceptability of the intervention. The reduction in anemia prevalence in the intervention group reflected an improvement in the knowledge of women related to anemia and nutrition during pregnancy. The training of health workers in the intervention zone on the prevention and management of anemia in pregnancy was beneficial to the adherence of pregnant women to the strategy.

Our results showed a good compliance with anemia prevention measures in both groups (e.g., iron/folate intake, use of mosquito nets), although compliance was not assessed through observable criteria in the control group as it was in the intervention group. This allows us to assume that the effect of the intervention would be, to a large extent, linked to better nutrition for pregnant women. The improvement in the diet of pregnant women was evidenced by the good rates of compliance with the commitments made by women and/or their husbands in relation to food intake. The difference in the prevalence of anemia between the two groups was significant only after four home visits, corresponding to approximately 4 months of follow-up; if a shorter follow-up period had been used, it would not have been possible to objectively establish this difference.

CONCLUSION

Our data demonstrate that the prevalence of anemia in pregnancy remains high in Burkina Faso and that personalized support for pregnant women at home, focusing on nutritional counseling, iron and folic acid supplementation, and prevention of malaria and intestinal parasites, combined with appropriate antenatal care, greatly reduces the prevalence of anemia in pregnancy.

Acknowledgments:

We thank the health care providers and participants from the Sindou district for their full availability throughout the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization , 2015. The Global Prevalence of Anaemia in 2011. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahman MM, Abe SK, Rahman MS, Kanda M, Narita S, Bilano V, Ota E, Gilmour S, Shibuya K, 2016. Maternal anemia and risk of adverse birth and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 103: 495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young MF, Oaks BM, Tandon S, Martorell R, Dewey KG, Wendt AS, 2019. Maternal hemoglobin concentrations across pregnancy and maternal and child health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1450: 47–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muñoz M, et al. 2018. Patient blood management in obstetrics: management of anaemia and haematinic deficiencies in pregnancy and in the post-partum period: NATA consensus statement. Transfus Med 28: 22–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keats EC, Haider BA, Tam E, Bhutta ZA, 2019. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD004905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh JK, Acharya D, Paudel R, Gautam S, Adhikari M, Kushwaha SP, Park JH, Yoo SJ, Lee K, 2020. Effects of female community health volunteer capacity building and text messaging intervention on gestational weight gain and hemoglobin change among pregnant women in southern Nepal: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Front Public Health 8: 312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bharti S, Bharti B, Naseem S, Attri SV, 2015. A community-based cluster randomized controlled trial of “directly observed home-based daily iron therapy” in lowering prevalence of anemia in rural women and adolescent girls. Asia Pac J Public Health 27: NP1333–NP1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ampofo GD, Tagbor H, Bates I, 2018. Effectiveness of pregnant women’s active participation in their antenatal care for the control of malaria and anaemia in pregnancy in Ghana: a cluster randomized controlled trial ISRTCTN88917252 ISRTCTN. Malar J 17: 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott S, et al. 2019. Community-based malaria screening and treatment for pregnant women receiving standard intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine: a multicenter (The Gambia, Burkina Faso, and Benin) cluster-randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 68: 586–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kesteman T, Randrianarivelojosia M, Rogier C, 2017. The protective effectiveness of control interventions for malaria prevention: a systematic review of the literature. F1000 Res 6: 1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (INSD) Burkina Faso, 2010. Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples (EDS MICS IV). Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso: INSD.

- 12.Meda N, Dao Y, Touré B, Yameogo B, Cousens S, Graham W, 1999. Évaluer l’anémie maternelle sévère et ses conséquences: la valeur d’un simple examen de la coloration des conjonctives palpébrales. Cah d’études Rech Francoph 9: 12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meda N, Coulibaly M, Nebie Y, Diallo I, Traore Y, Ouedraogo LT, 2016. Magnitude of maternal anaemia in rural Burkina Faso: contribution of nutritional factors and infectious diseases. Adv Public Health 2016: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black RE, et al. 2017. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 8. summary and recommendations of the expert panel. J Glob Health 7: 010908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ARES , 2016. Programme Interuniversitaire Ciblé. Available at: https://www.ares-ac.be/images/prd-pfs/rapports/ARES-PRD_Rapport-de-resultats-des-programmes-2008-2009.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2016.

- 16.Sanchis-Gomar F, Cortell-Ballester J, Pareja-Galeano H, Banfi G, Lippi G, 2013. Hemoglobin point-of-care testing. J Lab Autom 18: 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown AW, Li P, Brown MMB, Kaiser KA, Keith SW, Oakes JM, Allison DB, 2015. Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: designing, analyzing, and reporting cluster randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr 102: 241–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donner A, Birkett N, Buck C, 1981. Randomization by cluster: sample size requirements and analysis. Am J Epidemiol 114: 906–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donner A, Klar N, 2000. Design and Analysis of Cluster Randomization Trials in Health Research. London, UK: Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Medical Association , 2018. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available at: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/. Accessed December 19, 2018.

- 21.Nguyen PH, et al. 2018. Engagement of husbands in a maternal nutrition program substantially contributed to greater intake of micronutrient supplements and dietary diversity during pregnancy: results of a cluster-randomized program evaluation in Bangladesh. J Nutr 148: 1352–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Etheredge AJ, et al. 2016. Iron supplementation among iron-replete and non-anemic pregnant women: a randomized placebo-controlled trial in Tanzania Analee. JAMA Pediatr 169: 947–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daru J, Cooper NAM, Khan KS, 2016. Systematic review of randomized trials of the effect of iron supplementation on iron stores and oxygen carrying capacity in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 95: 270–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahamed F, Yadav K, Kant S, Saxena R, Bairwa M, Pandav CS, 2018. Effect of directly observed oral iron supplementation during pregnancy on iron status in a rural population in Haryana: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J Public Health 62: 287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keats EC, Haider BA, Tam E, Bhutta ZA, 2019. Multiple-micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasricha SR, Drakesmith H, Black J, Hipgrave D, Biggs B-AA, 2013. Control of iron deficiency anemia in low- and middle-income countries. Blood 121: 2607–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nsibu CN, Manianga C, Kapanga S, Mona E, Pululu P, Aloni MN, 2016. Determinants of antenatal care attendance among pregnant women living in endemic malaria settings: experience from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Obstet Gynecol Int 2016: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ministère de la Santé_Burkina Faso, 2019. Annuaire Statistique 2018. Ouagadougou.