Abstract.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis, which is the most common form of leishmaniasis, classically presents as small erythematous papules and nodules that develop into ulcers with indurated, raised outer borders. However, lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis can have pleomorphic and atypical presentations. The erysipeloid form is one of the rare, atypical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Reported is a case of a 58-year-old man from the hilly region of Nepal who presented with an atypical erythematous and edematous plaque over the left antecubital fossa. Cutaneous leishmaniasis was not considered as an initial diagnosis because of the atypical appearance of the lesion as well as his residence in the hilly region of Nepal. The diagnosis was made after detection of amastigotes on histopathological examination of a cutaneous biopsy specimen. There was complete regression of the lesion after treatment with oral miltefosine followed by oral fluconazole. Clinicians should be aware of atypical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis and it should be considered in the differential diagnosis, regardless of the presentation or geographic location.

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis is a widespread vector-borne parasitic disease, the severity of which ranges from mild cutaneous lesions to severe visceral disease.1 The disease is caused by protozoan parasites from more than 20 leishmania species. It is transmitted via the bite of infected female sandflies of the genus Phlebotomus in the Old World and Lutzomyia in the New World.2 There are around 70 animal species, including humans, that are reservoirs for leishmania.3 In the Indian subcontinent humans, dogs, rock hyraxes, and rodents are reported to be the major reservoirs.4 Leishmaniasis has been divided into cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral types.2 Clinical manifestations of leishmaniasis depend on various factors, including immune status, age, nutritional status, and genetic background of the host as well as inoculation site, dose, vector, and infecting species.5 Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is the most common and least severe form of the disease, which usually manifests as self-healing ulcers.6 There are many species of the Leishmania genus that cause CL. In Nepal, CL has been reported to be caused by Leishmania major,7 Leishmania donovani complex,8 and Leishmania tropica.9 Humans are the principal reservoir host for L. tropica and L. donovani, whereas rodents are the reservoirs of L. major.4

In 2019, the WHO included 98 countries and territories as endemic areas for leishmaniasis. In 2019, more than 91% of CL cases occurred in 12 countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Colombia, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Morocco, Pakistan, Peru, the Syrian Arab Republic and Tunisia.10 Nepal is one of the 71 countries in the world in which both cutaneous and visceral forms of leishmaniasis are endemic.10,11,12 According to the WHO, 16 cases of CL occurred in Nepal in 2019.13 Despite being an endemic country for leishmaniasis, documented cases of CL from Nepal are limited.7–9,14–20 Only one case report of erysipeloid CL has been published from Nepal.20 This is the second case of erysipeloid CL from Nepal to be documented in the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old man presented with a solitary, large, edematous, erythematous plaque over his left antecubital fossa that extended proximally to the arm and distally to the forearm (Figure 1A). He heralded from the Okhaldhunga District, which is located in the hilly region of eastern Nepal (Figure 2). At the time of evaluation, the lesion measured 10 × 12 cm in diameter. It started as a small erythematous papule that gradually progressed over a 5-month period into the plaque form. The patient complained of mild itching, and a burning and pricking sensation. He was a farmer by occupation. There was no known history of trauma. There was no history of fever, chills, night sweats, or weight loss. He had no travel history in the past 2 years. He had no significant history of any past illness or history of any drug intake. On examination, he had mild unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy. His general physical examination was unremarkable.

Figure 1.

(A) Erythematous, edematous plaque on left antecubital fossa extending to left arm and forearm. (B) Healed lesion with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Figure 2.

Highlight of the Okhaldhunga District (red) in the hilly region of Nepal. In the upper belt of Nepal lies the Himalayan region; middle belt, the hilly region; and the lowermost belt is the plain or terai region. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

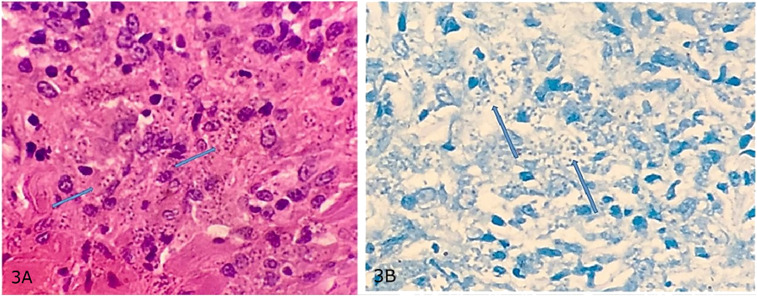

A skin biopsy was done and sent for analysis. Because of the uncommon appearance of the lesion, CL was not considered initially in the differential diagnosis. Considering the granulomatous and edematous nature of the lesion, several possible diagnoses were considered, including cutaneous tuberculosis, leprosy, cutaneous pseudo-lymphoma, and lymphocytoma cutis. Histopathological evaluation of the specimen demonstrated dermis with dense inflammatory and granulomatous infiltration with lymphohistiocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells. There were abundant intracellular amastigotes within macrophages seen on both hematoxylin–eosin and Giemsa staining (Figure 3A and B). Hence, the diagnosis of atypical erysipeloid presentation of CL was made. Because of the patient’s financial limitations, a polymerase chain reaction to identify the species was not done. Routine blood investigations, including liver and renal function tests, urinalysis, and chest X-ray, were normal. ELISA for HIV antibodies was non-reactive.

Figure 3.

(A) Hematoxylin–eosin staining demonstrating numerous amastigotes within macrophages (blue arrows; ×100 magnification). (B) Giemsa staining demonstrating the same (blue arrows; ×40 magnification). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

The patient was started on oral miltefosine 50 mg three times a day for 28 days. The lesion regressed after 28 days of treatment. The patient experienced no side effects to miltefosine. However, he presented again with peripheral expansion of the lesion after 41 days of completion of therapy. He was then prescribed oral fluconazole 200 mg daily for 6 weeks, after which there was complete regression of the lesion, resulting in post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B). No scarring was noted.

DISCUSSION

CL, which is the most common form of leishmaniasis, is classically characterized by the development of small papules and nodules the progress into ulcers with indurated, raised borders over the following few months.6 The incubation period can vary from a few days to 3 years. Lesions are usually located on exposed areas of the body, such as the face and extremities, and evolve over weeks to months.2,5 Various atypical lesions of CL have been described and include erythematous volcanic ulcer, diffuse, eczematous, lupoid, verrucous, dry, zosteriform, nodular, erysipeloid, sporotrichoid, annular, paronychial, palmoplantar and psoriasiform lesions.6

The erysipeloid form of CL has been reported from few countries around the world, and the volume of literature on this form of CL is sparce.6,20–25 The incidence rate of the erysipeloid form of CL has been reported to range between 0.05% and 3.2%.6 The erysipeloid type of lesions have mostly been reported to occur over the face and nose as a butterfly-shaped erythematous plaque.24,25 However, in our patient, it presented on an extremity. Although less common, presentation on extremities has been mentioned in the literature.6,26

The erysipeloid form of CL often presents in elderly patients, as in our case.23–25 Senility-induced skin fragility, altered immune response of the host, as well as a specific strain of leishmania infection could be the reason for the development of the erysipeloid form of CL.21,25 In the erysipeloid form, the spread of the infectious agents in the superficial layer of the papillary dermis could be the result of immune system failure to control parasite replication and local granuloma formation.25 Trauma has also been implicated as one of the factors that facilitates development of the erysipeloid form of CL.21,24 In our case, the patient did not have any history of trauma; however, because the patient is a farmer by occupation, unnoticed micro-trauma cannot be ruled out.

Our patient comes from the Okhaldhunga District, which falls within the hilly region of Nepal, with an altitude of approximately 1,500 m. The habitat of leishmania species is typically seen in areas of lower altitude; however, recent reports describe its presence in higher altitude areas.8,27 In Nepal, 18 districts are considered endemic for visceral leishmaniasis, among which 6 new districts, including this hilly district, were recently added as an endemic region in 2016.28 The reason for the dissemination of leishmaniasis cases to new areas could include climate change, deforestation, urbanization, frequent travel, immigration from endemic areas, and military operations.5

Depending on the size, number, location, and evolution of lesions, and the immunological and general health status of the patient, various topical and oral treatments of CL have been recommended in Nepal.20,28,29 As a result of the large size and evolving nature of the lesion, our patient was started on oral miltefosine. However, because the lesion relapsed after completing the full course of oral miltefosine, the patient was started on oral fluconazole as an alternative treatment as per the treatment protocol.28 Lack of a complete response to miltefosine could be a result of the type of leishmania species responsible for the infection as well as due to development of drug resistance.30–32 Unfortunately, we could not identify the species responsible for the infection in our patient.

In 2019, 16 cases of CL were reported in Nepal.13 Although Nepal is one of the endemic countries for CL, the government of Nepal has not defined districts endemic for CL. Data and literature on CL and its various types from Nepal are limited. Our case report provides insight regarding the clinical presentation of an atypical erysipeloid form of CL, its response to treatment, and its expansion to hilly regions. This insight might prompt further research into these areas.

In summary, because CL can have variable manifestations, any atypical-appearing lesion—especially on exposed areas of the body—be investigated for CL regardless of area of residence, especially on the Indian subcontinent. Disease progression can be controlled with early diagnosis and treatment, which can contribute toward a reduction in the prevalence rate.

Acknowledgment:

The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) assisted with publication expenses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burza S, Croft SL, Boelaert M, 2018. Leishmaniasis. Lancet 392: 951–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Handler MZ, Patel PA, Kapila R, Al-Qubati Y, Schwartz RA, 2015. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol 73: 897–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization , 2020. Leishmaniasis. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis. Accessed April 29, 2021.

- 4.Alemayehu B, Alemayehu M, 2017. Leishmaniasis: a review on parasite, vector and reservoir host. Health Sci J 11: 519. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kevric I, Cappel MA, Keeling JH, 2015. New World and Old World Leishmania infections: a practical review. Dermatol Clin 33: 579–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meireles CB, Maia LC, Soares GC, Teodoro IPP, Gadelha MDSV, da Silva CGL, de Lima MAP, 2017. Atypical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis: a systematic review. Acta Trop 172: 240–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar R, Ansari NA, Avninder S, Ramesh V, Salotra P, 2008. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Nepal: Leishmania major as a cause. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 102: 202–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastola A, et al. 2020. A case of high altitude cutaneous leishmaniasis in a non-endemic region in Nepal. Parasitol Int 74: 101991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parija SC, Jacob M, Karki BM, Sethi M, Karki P, Koirala S, 1998. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Nepal. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 29: 131–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization , 2021. Leishmaniasis. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/leishmaniasis. Accessed April 29, 2021.

- 11.World Health Organization , 2021. Leishmaniasis. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/status-of-endemicity-of-visceral-leishmaniasis. Accessed April 29, 2021.

- 12.World Health Organization , 2021. Leishmaniasis. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/status-of-endemicity-of-cutaneous-leishmaniasis. Accessed April 29, 2021.

- 13.World Health Organization , 2021. Leishmaniasis. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: https://apps.who.int/neglected_diseases/ntddata/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis.html. Accessed April 29, 2021.

- 14.Karki P, Parija SC, George S, Das ML, Koirala S, 1997. Visceral leishmaniasis with cutaneous ulcer or cutaneous leishmaniasis in Nepal. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 28: 836–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandey BD, Babu E, Thapa S, Thapa LB, 2006. First case of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Nepalese patient. Nepal Med Coll J 8: 213–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neupane S, Sharma P, Kumar A, Paudel U, Pokhrel DB, 2008. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: report of rare cases in Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J 10: 64–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paudel U, Parajuli S, Poudel AS, Paudel V, Pokhrel DB, 2019. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in natives of central region of Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J 65: 77–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghimire P, Shrestha R, Pandey S, Pokhrel K, Pande R, 2018. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: a neglected vector borne tropical disease in midwestern region of Nepal. Nepal J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 16: 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paudel V, Parajuli S, Chudal D, 2020. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Nepal: an emerging public health concern. Our Dermatol Online 11: 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parajuli N, Adhikary S, Karki A, Tiwari S, 2021. Case report: erysipeloid cutaneous leishmaniasis treated with oral miltefosine. Am J Trop Med Hyg 104: 643–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozdemir M, Cimen K, Mevlitoglu I, 2007. Post-traumatic erysipeloid cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol 46: 1292–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bongiorno MR, Pistone G, Aricò M, 2009. Unusual clinical variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sicily. Int J Dermatol 48: 286–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karincaoglu Y, Esrefoglu M, Ozcan H, 2004. Atypical clinical form of cutaneous leishmaniasis: erysipeloid form. Int J Dermatol 43: 827–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mnejja M, Hammami B, Chakroun A, Achour I, Charfeddine I, Chakroun A, Turki H, Ghorbel A, 2011. Unusual form of cutaneous leishmaniasis: erysipeloid form. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 128: 95–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akilov OE, Khachemoune A, Hasan T, 2007. Clinical manifestations and classification of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol 46: 132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remadi L, Haouas N, Chaara D, Slama D, Chargui N, Dabghi R, Jbeniani H, Mezhoud H, Babba H, 2016. Clinical presentation of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major. Dermatology 232: 752–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shrestha M, Pandey BD, Maharjan J, Dumre SP, Tiwari PN, Manandhar KD, Pun SB, Pandey K, 2018. Visceral leishmaniasis from a non-endemic Himalayan region of Nepal. Parasitol Res 117: 2323–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Population, Government of Nepal , 2019. National Guideline on Kala-Azar Elimination Program (Updated) 2019. Available at: http://www.edcd.gov.np/resources/download/national-guideline-on-kala-azar-elimination-program-2019. Accessed January 18, 2021.

- 29.World Health Organization , 2014. Manual for Case Management of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. WHO Regional Publications, Eastern Mediterranean Series. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monge-Maillo B, López-Vélez R, 2015. Miltefosine for visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis: drug characteristics and evidence-based treatment recommendations. Clin Infect Dis 60: 1398–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosimann V, Blazek C, Grob H, Chaney M, Neumayr A, Blum J, 2016. Miltefosine for mucosal and complicated cutaneous Old World leishmaniasis: a case series and review of the literature. Open Forum Infect Dis 3: ofw008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorlo TP, van Thiel PP, Huitema AD, Keizer RJ, de Vries HJ, Beijnen JH, de Vries PJ, 2008. Pharmacokinetics of miltefosine in Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52: 2855–2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]