Abstract.

Diarrheal disease is the second most frequent cause of mortality in children younger than 5 years worldwide, causing more than half a million deaths each year. Our knowledge of the epidemiology of potentially pathogenic agents found in children suffering from diarrhea in sub-Saharan African countries is still patchy, and thereby hinders implementation of effective preventative interventions. The lack of cheap, easy-to-use diagnostic tools leads to mostly symptomatic and empirical case management. An observational study with a total of 241 participants was conducted from February 2017 to August 2018 among children younger than 5 years with diarrhea in Lambaréné, Gabon. Clinical and demographic data were recorded, and a stool sample was collected. The samples were examined using a commercial rapid immunoassay to detect Rotavirus/adenovirus, conventional bacterial culture for Salmonella spp., and multiplex real-time PCR for Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia lamblia, Cyclospora cayetanensis, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC)/Shigella. At least one infectious agent was present in 121 of 241 (50%) samples. The most frequently isolated pathogens were EIEC/Shigella and ETEC (54/179; 30.2% and 44/179; 24.6%, respectively), followed by G. lamblia (33/241; 13.7%), Cryptosporidium spp. (31/241; 12.9%), and Rotavirus (23/241; 9.5%). Coinfection with multiple pathogens was observed in 33% (40/121) of the positive cases with EIEC/Shigella, ETEC, and Cryptosporidium spp. most frequently identified. Our results provide new insight into the possible causes of diarrheal disease in the Moyen-Ogooué region of Gabon and motivate further research on possible modes of infection and targeted preventive measures.

INTRODUCTION

More than half a million deaths of children younger than 5 years worldwide are caused by diarrheal disease each year, with countries with a lower sociodemographic index disproportionally affected.1 It is overall the second most frequent cause of death in children aged between 1 and 60 months.2 Both the diagnosis and treatment of diarrheal disease require substantial improvements toward fulfilling the ambitious sustainable development goals, which call for a reduction of under-five mortality worldwide to no more than 25 deaths per 1,000 live births by 2030.3

The management of diarrhea as recommended by the WHO mainly promotes symptomatic case management in children.4 Although very effective, in many cases, further decreases in morbidity and mortality will rely on more targeted, specific therapies and prevention strategies.

The last few years have seen a number of studies that have examined the spectrum of pathogens responsible for diarrhea in children, the most notable of these being the global enteric multicenter study (GEMS),5 which revealed a heretofore unexpected spectrum of pathogens, most notably comprising Cryptosporidium spp.6,7 These findings also highlighted the need to update the regional maps of the epidemiology of diarrheal pathogens.

In Gabon, no comprehensive studies on the etiology of infantile diarrhea have been conducted. There are only isolated studies on the bacterial,8 viral,9 or very specific parasitic causes of diarrhea, namely, Cryptosporidium spp.10,11 Furthermore, there is only a limited number of studies available on diarrhea in children in the whole of Central African region, especially in the recent literature (two reports from the Central African Republic [CAR]12 and Angola13).

Here, we report data from a survey of pathogens found in stool of children younger than 5 years presenting with diarrhea at two hospitals in Lambaréné, a semi-urban town of Gabon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of the Centre de Recherches Médicales de Lambaréné (CERMEL) (CEI-CERMEL: 003/2017). Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians of all including participants.

Study design.

This study was designed as a cross-sectional study and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2018. It is part of a larger cross-sectional study entitled “Genetic determinants for the transmission of Cryptosporidium parvum/hominis among humans and animals in Africa,” which aimed to identify Cryptosporidium transmission networks and reservoirs in Gabon, Ghana, Madagascar, and Tanzania by tracing infected children to their closest human and animal contacts (PMIDs: 32150243 and 32658930).

Study population and site.

Children aged between 0 and 5 years presenting at the outpatient departments of the two main hospitals in Lambaréné, Gabon, the Hôpital Albert Schweitzer, and the Centre Hôspitalier Régional Georges Rawiri de Lambaréné, were screened and included in this study if they presented with diarrhea (defined as the passage of three or more liquid stools within 24 hours during the last 3 days), provided a stool sample, and lived within the study area, which spanned a radius of approximately 20 km around the city of Lambaréné situated in the Moyen-Ogooué region. The region is irrigated by the Ogooué River and its tributaries, with many ponds, lakes, and streams, constituting favorable conditions for waterborne pathogens.

At the time that this study was conducted, the Rotavirus vaccine had not yet been included in the national vaccination programme in Gabon.

Children enrolled in the study.

Children presenting at one of two hospitals with diarrhea between February 2017 and February 2018 were invited to participate in the study. The participants came from Lambaréné, the capital of the province of Moyen Ogooué of Gabon, and the surrounding villages, which constitutes a more rural setting with no running water and electricity, and less access to the healthcare system.

Field and laboratory procedures.

All personnel involved in the project activities were trained on screening procedures, and recording of demographic and clinical data, sample collection, and transportation to the laboratory. To assess the level of dehydration, we used a clinical dehydration score.14 A fresh stool sample was provided by each child in a labeled leak-proof stool container within 48 hours after inclusion.

Detection of pathogens was performed by different standard methods5 and diagnostic kits as described by the manufacturers. In brief, Rotavirus and adenovirus were detected using a rapid diagnostic test (SD Rota/Adeno Rapid; Standard Diagnostics, Hagal-dong, Giheung-gu, Yongin-si, Kyonggi-do, Korea). Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC)/Shigella were identified by performing a real-time PCR using a specific kit (RIDA®GENE ETEC/EIEC multiplex real-time PCR, Darmstadt, Germany). For Salmonella spp., a standard culture was performed.16,17 Another real-time PCR was used to assess the presence of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia lamblia, and Cyclospora cayetanensis using specific primers and probes as described elsewhere.18

Statistical analysis.

Data analysis was performed using R version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). We calculated the point prevalence of enteric pathogens as the ratio of the number of detected cases per number of patients with evaluable test results for a specific pathogen at the time of presentation to the outpatient or inpatient departments. The assessment of association between categorical variables (or comparison of proportions between different groups: mono-infected, coinfected) was performed with chi-squared test or Fisher’s test. For the association between pathogens and age-groups, gender, residence, and odds ratios with 95% CIs were calculated. We calculated binomial 95% CIs for proportions and performed chi-squared tests, and a two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics.

A total of 329 children presenting at one of the two study hospitals were screened; of these, 241 children were then recruited in the study and gave a stool sample (Supplemental Figure S1 and Table S1); 149 (61.8%) were males and 92 females (38.2%). Sixty-four (27.2%) children were younger than 7 months, 69 (39.4%) were aged between 7 and 12 months, and the remaining 102 (43.4%) were aged between 13 and 59 months. The majority (170/205; 82.9%) of the participants lived in an urbanized area (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | n (%) | Binomial 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age-group (months) (N = 235) | ||

| 0–6 | 64 (27.2) | 19.8–31.1 |

| 7–12 | 69 (29.4) | 24.3–36.2 |

| 13–59 | 102 (43.4) | 37.9–50.7 |

| Gender (N = 241) | ||

| Female | 92 (38.2) | 32–44.3 |

| Male | 149 (61.8) | 55.7–68 |

| Residence (N = 205) | ||

| Rural | 35 (17.1) | 11.9–22.2 |

| Urban | 170 (82.9) | 77.8–88.1 |

| Vomiting (N = 215) | ||

| No | 120 (55.8) | 49-2-62.5 |

| Yes | 95 (44.2) | 37.5–50.8 |

| Bloody or mucoid stool (N = 232) | ||

| No | 95 (40.9) | 34.6–47.6 |

| Yes | 137 (59.1) | 52.4–65.4 |

| Dehydration (N = 199) | ||

| None | 63 (31.7) | 25.2–38.1 |

| Mild | 109 (54.8) | 47.9–61.7 |

| Moderate | 26 (13) | 8.4–17.7 |

| Severe | 1 (0.5) | 0–1.5 |

| Fever (N = 233) | ||

| No | 77 (33) | 27–39.1 |

| Yes | 156 (67) | 60.9–73 |

| Anorexia (N = 229) | ||

| No | 88 (38.4) | 32.1–44.7 |

| Yes | 141 (61.6) | 55.3–67.9 |

A total of 199 patients completed the clinical examination. Among those, 63 (31.7%) patients showed no signs of dehydration, whereas 109 (54.8%) were mildly, 26 (13%) moderately, and one (0.5%) child was severely dehydrated. For 137 of 232 participants (59.1%), bloody or mucoid stool was reported, and the most common additional symptoms were, in decreasing order, fever (156/233; 67%), anorexia (141/229; 61.6%), and vomiting (95/215; 44.2%). The number of symptomatic children included in our study varied over time (Supplemental Figure S2).

Detection of enteric pathogens.

Of the 241 samples collected, 179 samples could be tested for EIEC/Shigella and ETEC using Multiplex real-time PCR, because of an insufficient amount of biological material. No pathogen was identified in 58 children of 179 who provided stool samples (Supplemental Table S1). Thirty percent (n = 54) of the samples were positive for EIEC/Shigella and 24.6% (n = 44) for ETEC.

Giardia lamblia was identified in 13.7% (n = 33), Cryptosporidium in 12.9% (n = 31), and Rotavirus in 9.5% (n = 23) of the samples (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of pathogens detected in children with diarrhea

| Pathogen | n (%) | N tested |

|---|---|---|

| Giardia lamblia | ||

| Positive | 33 (13.7) | 241 |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | ||

| Positive | 31 (12.9) | 241 |

| Cyclospora cayetanensis | ||

| Positive | 8 (3.3) | 241 |

| Rotavirus | ||

| Positive | 23 (9.5) | 241 |

| Adenovirus | ||

| Positive | 8 (3.3) | 241 |

| Salmonella spp. | ||

| Positive | 5 (2.1) | 241 |

| Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli | ||

| Positive | 44 (24.6) | 179 |

| Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli/Shigella | ||

| Positive | 54 (30.2) | 179 |

Proportion of coinfections.

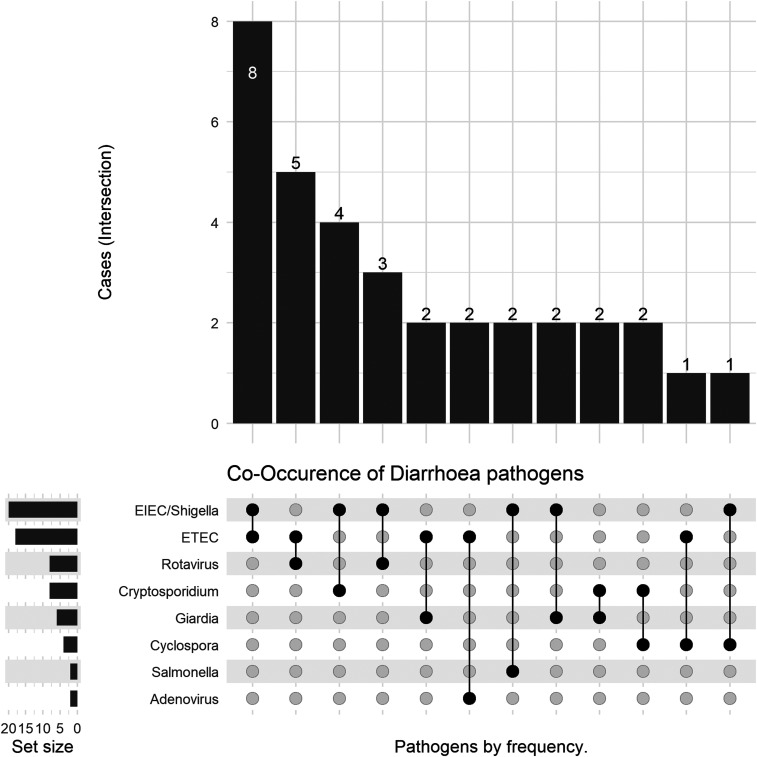

Of the 179 samples that had been screened for all the eight studied pathogens, 121 were infected with at least one pathogen. Among these positive samples, 40 (33%) contained more than one pathogen, with dual, triple, and more infections being recorded. Of these 40 stool samples, dual infection was detected in 34 specimens, three pathogens could be simultaneously identified in five samples, and one sample was positive for four pathogens. The most frequently detected pathogens in combination were the two E. coli pathotypes (EIEC/Shigella [65%] and ETEC [60%]) followed by Cryptosporidium spp. (25%), Rotavirus, and G. lamblia (22%) (Table 3). Among these, the most frequently observed combinations of pathogens were EIEC/Shigella and ETEC, ETEC and Rotavirus, and Cryptosporidium and EIEC/Shigella (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Prevalence of coinfections

| Pathogen | Prevalence among mono-infected subjects (N = 81), n (%) | Prevalence among coinfected subjects (N = 40), n (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus | 3 (3.7) | 3 (7.5) | 0.65 |

| Rotavirus | 11 (13.6) | 9 (22.5) | 0.33 |

| G. lamblia | 10 (12.3) | 9 (22.5) | 0.24 |

| Cryptosporidium spp. | 6 (7.4) | 10 (25) | 0.02 |

| C. cayetanensis | 1 (1.2) | 4 (10) | 0.07 |

| Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli | 20 (24.7) | 24 (60) | < 0.001 |

| Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli/Shigella | 28 (34.6) | 26 (65) | 0.003 |

| Salmonella spp. | 2 (2.4) | 2 (5) | 0.20 |

Only data from n = 179 with full diagnostics are included.

Figure 1.

Dual pathogen combinations among enteropathogens identified in diarrheal disease.

Association between pathogen carrier status and demographic data.

Table 4 summarizes the association between key demographic characteristics (age, gender, and area of residence) of children with diarrhea and potential pathogens causing diarrhea detected in these children. A significant association could be observed for three pathogens and age-group. Giardia lamblia was significantly associated with the age-group of 0–6 months (odds ratio [OR]: 0.29; 95% CI: 0.08–0.8, P = 0.03) and the age-group of 7–12 months (OR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.16–1.0, P = 0.03). Rotavirus and EIEC/Shigella showed, respectively, a significant association with the age-group of 7–12 months (Rotavirus: OR: 0.2; 95% CI: 0.03–0.6, P = 0.001; EIEC/Shigella: OR: 1.5; 95% CI: 0.6–4.0, P = 0.02) and the age-group of 13–59 months (Rotavirus: OR: 0.3; 95% CI: 0.1–0.7, P = 0.001; EIEC/Shigella: OR: 3.0; 95% CI: 1.3–7.7, P = 0.02). The distribution of most pathogens was similar across age-groups and with respect to area of residence, with the exception of Rotavirus, which was more frequently found in infants aged < 6 months and in subjects residing in an urban area. Giardia lamblia and ETEC on the other hand were more frequently identified in children older than 6 months.

Table 4.

Association between enteropathogens and demographic characteristics

| Variable | Rotavirus, n (%) | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Adenovirus, n (%) | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-group (months) | ||||||||

| 0–6 | 13 (22) | 1 | – | 0.001 | 0 (0) | – | – | 0.18 |

| 7–12 | 3 (4) | 0.17 | 0.03–0.56 | 4 (6) | – | – | – | |

| 13–59 | 7 (7) | 0.26 | 0.09–0.69 | 3 (3) | 1 | – | – | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 11 (12) | 1 | – | 0.44 | 1 (1) | 1 | – | 0.16 |

| Male | 12 (8) | 0.65 | 0.27–1.57 | 7 (5) | 3.99 | 0.68–103 | – | |

| Residence | ||||||||

| Rural | 2 (6) | 1 | – | 0.54 | 1 (3) | 1 | – | 1 |

| Urban | 19 (11) | 1.95 | 0.52–13.7 | – | 6 (4) | 1.12 | 0.18–29.6 | – |

| Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, n (%) | OR | 95% CI | P-value | G. lamblia, n (%) | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age-group (months) | ||||||||

| 0–6 | 12 (25) | 1 | – | 0.57 | 4 (7) | 0.29 | 0.08–0.82 | 0.03 |

| 7–12 | 14 (27) | 1.13 | 0.46–2.84 | – | 7 (10) | 0.43 | 0.16–1.05 | – |

| 13–59 | 13 (19) | 0.72 | 0.29–1.80 | – | 21 (21) | 1 | – | – |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 18 (27) | 1 | – | 0.65 | 18 (20) | 1 | – | 0.05 |

| Male | 26 (23) | 0.8 | 0.40–1.62 | – | 15 (10) | 0.46 | 0.21–0.96 | – |

| Residence | ||||||||

| Rural | 8 (25) | 1 | – | 1 | 6 (17) | 1 | – | 0.24 |

| Urban | 36 (25) | 0.97 | 0.41–2.5 | – | 17 (10) | 0.53 | 0.20–1.60 | – |

| Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli-Shigella, n (%) | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Salmonella, n (%) | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age-group (months) | ||||||||

| 0–6 | 9 (19) | 1 | – | 0.02 | 1 (2) | 0.62 | 0.02–5.52 | 0.86 |

| 7–12 | 13 (25) | 1.47 | 0.56–4.00 | – | 1 (1) | 0.52 | 0.02–4.62 | – |

| 13–59 | 28 (42) | 3.05 | 1.31–7.71 | – | 3 (3) | 1 | – | – |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 19 (29) | 1 | – | 0.89 | 0 (0) | 1 | – | 0.16 |

| Male | 35 (31) | 1.11 | 0.57–2.19 | – | 5 (3) | – | ||

| Residence | ||||||||

| Rural | 14 (44) | 1 | – | 0.09 | 1 (3) | 1 | – | 1 |

| Urban | 39 (27) | 0.47 | 0.21–1.05 | – | 4 (2) | 0.75 | 0.10–20.8 | – |

| Cryptosporidium, n (%) | OR | 95% CI | P-value | C. cayetanensis, n (%) | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age-group (months) | ||||||||

| 0–6 | 3 (5) | 1 | – | 0.11 | 1 (2) | 0.47 | 0.02–3.50 | 0.81 |

| 7–12 | 11 (16) | 3.33 | 0.96–16.1 | – | 3 (4) | 1.11 | 0.20–5.49 | – |

| 13–59 | 16 (16) | 3.3 | 1.03–15.3 | – | 4 (4) | 1 | – | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 13 (14) | 1 | – | 0.79 | 6 (7) | 1 | – | 0.06 |

| Male | 18 (12) | 0.83 | 0.39–1.84 | – | 2 (1) | 0.21 | 0.03–0.95 | – |

| Residence | ||||||||

| Rural | 7 (20) | 1 | – | 0.14 | 3 (9) | 1 | – | 0.06 |

| Urban | 17 (10) | 0.44 | 0.17–1.25 | – | 3 (2) | 0.19 | 0.03–1.17 | – |

OR = odds ratio; the reference category is indicated by OR = 1.

DISCUSSION

This study was the first of its kind conducted in Lambaréné, Gabon, and is overall one of very few studies conducted on this topic in the Central African region.8–10,12 The other studies conducted in Gabon, by Koko et al.,8 Lekana-Douki et al.,9 and Duong et al.,10 respectively, focused on specific infectious agents, either bacteria or Cryptosporidium spp., and therefore do not provide an epidemiological overview. Furthermore, these studies were conducted mainly in Libreville, a more urbanized setting than Lambaréné.

The most prevalent pathogens in our study were EIEC/Shigella and ETEC. This ties in well with the findings of the GEMS multicenter study, in which Shigella was identified as the number one pathogen and ETEC ranked fourth.19 Rota- and adenovirus were the second and third most prevalent enteric pathogens in the GEMS study.

A study conducted in Lambaréné, Gabon, in 1997, analyzing 150 participants’ stool for different strains of E. coli, had not found EIEC/Shigella in any of the samples. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli was identified in seven samples (4.7%), and EAEC was found in 57 samples (38%).20 Whether this considerable difference between our respective findings is due to an emergence of new strains of E. coli in this region or a different testing protocol cannot be conclusively answered. Samples collected as part of the said study were analyzed in Austria and only submitted for molecular diagnostic testing when the growth of suspect E. coli had been shown in culture, whereas in this current study, PCR was conducted regardless of results attained by conventional microbiological culture in our study.

Rotavirus was found in 9.5% of our patients, which is a lower prevalence than expected when reviewing the pertinent literature. This may be due to differing diagnostic methods because most of the other studies used molecular diagnostic methods, which are known to be more sensitive. Reported numbers vary between 27.1% in other parts of Gabon,9 25.1% in Angola,13 and 40.4% in the CAR.12 Each of these studies was conducted in the same age-group with similar inclusion criteria. The higher prevalence of Rotavirus in younger children with diarrhea as opposed to other pathogens in our study supports similar findings from the GEMS report, as well as the studies by Breurec et al.12 and Gasparinho et al.13

Adenovirus was only identified in 3.3% of our cases, whereas its prevalence in another study conducted in Gabon was 19.6%.9 Again, this discrepancy may reflect different methods of testing. The original GEMS analysis showed a prevalence of < 5% in diarrheal disease also using a rapid test, whereas a second analysis using molecular techniques showed a higher prevalence between 7% and 22% at different sites.5,19

The relatively recent discovery of Cryptopsoridium spp. as an important pathogen in childhood diarrhea6 can be further confirmed by our findings (12.9%), with the first cases of Cryptosporidium spp. infection recorded in this part of the country.21 There are estimates that up to 15–25% of children with diarrhea are infected with Cryptosporidium spp.22 A study in Angola found Cryptosporidium spp. in 30% of children presenting with diarrhea.13 Older studies conducted in Kenya and Mozambique found much lower numbers (4% and 0.6%, respectively).23,24 An earlier study on Cryptosporidium spp. in Gabon found a prevalence as high as 24% in children aged between 0 and 2 years with diarrhea.10 Many of the previous studies used microscopy, which is known to be less sensitive than molecular diagnostic tools such as PCR, leading to the discrepancies for Cryptosporidium spp. More generally, the often substantial differences in prevalence estimates stemming from different test technologies appear to be an important limitation for the interpretation of individual studies and hinder potential, more powerful meta-analyses.

The overall findings of this study highlight the need for further examination of the causes of childhood diarrhea and the pathogenesis thereof. Clearly, these results pose a significant question to routinely screen for diarrheagenic E. coli such as ETEC and EIEC in this region. Our study showed a high number of coinfections, which is similar to the findings of other studies in this field.5,25–28 The effect of these infections with multiple pathogens on the disease outcome, for example, whether they lead to more severe infection, is as yet not fully understood and calls for more focused research. Furthermore, the fact that some pathogens are more frequently involved in mixed infections could suggest that pathogen combinations can be found in the same contaminated foods or beverages from an area with imperfect sanitation conditions (28). In addition, the high proportion of coinfections could explain the fact that the pathogens detected might act synergistically in pathogenesis and contribute to the burden of diarrheal disease.29

The current WHO guidelines on the treatment of infantile diarrhea postulate mainly symptomatic treatment and antibiotic treatment only in cases where amoebiasis or giardiasis is suspected.4 More easily accessible diagnostic methods and a better knowledge regarding the prevalence of the different pathogens causing diarrhea could help avoid widespread unnecessary prescription of antibiotics.

With regard to the demographic characteristics of the study participants, there were noticeably more male children included (Table 1). Whether this is due to a higher susceptibility to diarrhea, families being more likely to seek professional health care for male children or pure chance cannot be conclusively determined. There was no gender bias in previous hospital-based studies conducted in Lambaréné.21,30 Overall, the spread of different pathogens was quite even in regard to the participants’ demographic characteristics, except for the age of participants. Table 4 shows that most of the pathogens had a higher prevalence in the youngest age-group. This finding is in line with observations made in previous studies reporting that Rotavirus, Cryptosporidium, ETEC, and adenovirus were more frequently detected in children during their first year of life.5,26 Particularly for children younger than 7 months, we observed a low proportion of most of the enteropathogens found in this study. This could be due to the fact that most children younger than 6 months were usually breastfed, which has been shown to have a preventative effect on gastrointestinal illnesses.20

The high number of patients with G. lamblia suggests considerable levels of contamination in the local water supply, because this pathogen has been mainly found to be transmitted by water in this demographic group.31 It is, however, not clear whether this parasite actually always represents a cause of diarrhea or may just be an accompanying colonization as has been suggested by several other authors.5,12,32,33

Limitations.

The main limitation of this study is the lack of a healthy control group. This excludes any firm attribution of pathogens identified to the symptoms witnessed. Many of these pathogens can also be found in healthy individuals, albeit usually in substantially lower quantity than in those presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms.19,34,35

Furthermore, we only tested for certain key pathogens, and thus, alternative pathogenic agents such as Campylobacter spp., Norovirus, or Entamoeba histolytica, to name a few, went undetected. In addition, the methods we used were not necessarily the most sensitive for the identification of the respective pathogens. A study by Li et al. has shown a significantly higher rate of adenovirus identified in samples when using molecular diagnostic methods as opposed to a commercial immunoassay as used in our study.26 Therefore, we consider the spectrum of pathogens identified in this study as preliminary data that can be used as a baseline for further studies.

CONCLUSION

In this first study of diarrheal pathogens in children in one of the peripheral cities in Gabon and surrounding villages, we identified a spectrum of infectious agents that can serve as baseline for public health stakeholders and guide more detailed future studies. These should include healthy control groups, to enable a more definite attribution of pathogenicity to the different infectious agents identified.

A better understanding of the spectrum of pathogens found in children with diarrhea and more readily available diagnostic methods could lead to a better adherence to the current WHO treatment guidelines and a more appropriate usage of antibiotics by the treating physicians.

Finally, the implementation of the Rotavirus vaccine into the national vaccination program could prove beneficial, particularly for the youngest age bracket examined in this study.

Supplemental tables and figure

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Danny Carrel Manfoumbi Mabicka and Jean Mermoz Ndong Essono Ondong for their support during sample pretreatment and storage. We extend our thanks to Adele Bia, our study nurse, and all participants.

Note: Supplemental tables and figures appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Troeger C, et al. 2017. Estimates of global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoeal diseases: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis 17: 909–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Chu Y, Perin J, Zhu J, Lawn JE, Cousens S, Mathers C, Black RE, 2016. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. Lancet 388: 3027–3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations , 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations General Assembly 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization , 2005. The Treatment of Diarrhoea: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotloff KL, et al. 2013. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the global enteric multicenter study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 382: 209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Striepen B, 2013. Parasitic infections: time to tackle cryptosporidiosis. Nature 503: 189–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossle NF, Latif B, 2013. Cryptosporidiosis as threatening health problem: a review. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 3: 916–924. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koko J, Ambara JP, Ategbo S, Gahouma D, 2013. Épidémiologie des diarrhées aiguës bactériennes de l’enfant à Libreville. Gabon Arch Pédiatrie 20: 432–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lekana-Douki SE, Kombila-Koumavor C, Nkoghe D, Drosten C, Drexler JF, Leroy EM, 2015. Molecular epidemiology of enteric viruses and genotyping of rotavirus A, adenovirus and astrovirus among children under 5 years old in Gabon. Int J Infect Dis 34: 90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duong TH, Kombila M, Dufillot D, Richard-Lenoble D, Owono Medang M, Martz M, Gendrel D, Engohan E, Moreno JL, 1991. Role of cryptosporidiosis in infants in Gabon. Results of two prospective studies. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 84: 635–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duong TH, Dufillot D, Koko J, Nze-Eyo’o R, Thuilliez V, Richard-Lenoble D, Kombila M, 1995. Cryptosporidiose digestive chez le jeune enfant en zone urbaine au Gabon. Santé 5: 185–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breurec S, et al. 2016. Etiology and epidemiology of diarrhea in hospitalized children from low income country: a matched case-control study in Central African Republic. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10: e0004283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasparinho C, Mirante MC, Centeno-Lima S, Istrate C, Mayer AC, Tavira L, Nery SV, Brito M, 2016. Etiology of diarrhea in children younger than 5 years attending the bengo general hospital in Angola. Pediatr Infect Dis J 35: e28–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldman RD, Friedman JN, Parkin PC, 2008. Validation of the clinical dehydration scale for children with acute gastroenteritis. Pediatrics 122: 545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savin C, Carniel E, 2009. Diagnostic des infections. Bactériol Méd 2016: 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dekker JP, Frank KM, 2015. Salmonella, Shigella, and yersinia. Clin Lab Med 35: 225–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verweij JJ, Blangé RA, Templeton K, Schinkel J, Brienen EA, van Rooyen MA, van Lieshout L, Polderman AM, 2004. Cryptosporidium parvum in fecal samples by using multiplex real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol 42: 1220–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, et al. 2016. Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to identify causes of diarrhoea in children: a reanalysis of the GEMS case-control study. Lancet 388: 1291–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Presterl E, Zwick RH, Reichmann S, Aichelburg A, Winkler S, Kremsner PG, Graninger W, 2003. Frequency and virulence properties of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in children with diarrhea in Gabon. Am J Trop Med Hyg 69: 406–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manouana GP, et al. 2020. Performance of a rapid diagnostic test for the detection of Cryptosporidium spp. in African children admitted to hospital with diarrhea. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14: e0008448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Checkley W, et al. 2015. A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for Cryptosporidium. Lancet Infect Dis 15: 85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gatei W, Wamae CN, Mbae C, Waruru A, Mulinge E, Waithera T, Gatika SM, Kamwati SK, Revathi G, Hart CA, 2006. Cryptosporidiosis: prevalence, genotype analysis, and symptoms associated with infections in children in Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg 75: 78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandomando IM, et al. 2007. Etiology of diarrhea in children younger than 5 years of age admitted in a rural hospital of Southern Mozambique. Am J Trop Med Hyg 76: 522–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen SY, Tsai CN, Chao HC, Lai MW, Lin TY, Ko TY, Chiu CH, 2009. Acute gastroenteritis caused by multiple enteric pathogens in children. Epidemiol Infect 137: 932–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li LL, Liu N, Humphries EM, Yu JM, Li S, Lindsay BR, Stine OC, Duan ZJ, 2016. Aetiology of diarrhoeal disease and evaluation of viral-bacterial coinfection in children under 5 years old in China: a matched case-control study. Clin Microbiol Infect 22: 381.e9–381.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stockmann C, et al. 2017. Detection of 23 gastrointestinal pathogens among children who present with diarrhea. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc 6: 231–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang SX, et al. 2016. Impact of co-infections with enteric pathogens on children suffering from acute diarrhea in southwest China. Infect Dis Poverty 5: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shrivastava AK, Kumar S, Mohakud NK, Suar M, Sahu PS, 2017. Multiple etiologies of infectious diarrhea and concurrent infections in a pediatric outpatient-based screening study in Odisha, India. Gut Pathog 9: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krumkamp R, et al. 2020. Transmission of Cryptosporidium species among human and animal local contact networks in sub-saharan Africa: a multicountry study. Clin Infect Dis ciaa223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leclerc H, Schwartzbrod L, Dei-Cas E, 2002. Microbial agents associated with waterborne diseases. Crit Rev Microbiol 28: 371–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nhampossa T, et al. 2015. Diarrheal disease in rural Mozambique: burden, risk factors and etiology of diarrheal disease among children aged 0-59 months seeking care at health facilities. PLoS One 10: 12–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muhsen K, Levine MM, 2012. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between Giardia lamblia and endemic pediatric diarrhea in developing countries. Clin Infect Dis 55 (Suppl 4): S271–S293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krumkamp R, Sarpong N, Georg Schwarz N, Adelkofer J, Loag W, Eibach D, Matthias Hagen R, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Tannich E, May J, 2015. Gastrointestinal infections and diarrheal disease in Ghanaian infants and children: an outpatient case-control study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9: e0003728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Platts-Mills JA, et al. 2014. Association between stool enteropathogen quantity and disease in Tanzanian children using TaqMan array cards: a nested case-control study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 90: 133–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.