Abstract

The rapid increase in obesity, diabetes and fatty liver disease in children over the past 20 years has been linked to increased consumption of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), making it essential to determine the short- and long-term effects of HFCS during this vulnerable developmental window. We hypothesized that HFCS exposure during adolescence significantly impairs hepatic metabolic signalling pathways and alters gut microbial composition, contributing to changes in energy metabolism with sex-specific effects. C57bl/6J mice with free access to HFCS during adolescence (3–6 weeks of age) underwent glucose tolerance and body composition testing and hepatic metabolomics, gene expression and triglyceride content analysis at 6 and 30 weeks of age (n = 6–8 per sex). At 6 weeks HFCS-exposed mice had significant increases in fat mass, glucose intolerance, hepatic triglycerides (females) and de novo lipogenesis gene expression (ACC, DGAT, FAS, ChREBP, SCD, SREBP, CPT and PPARα) with sex-specific effects. At 30 weeks, HFCS-exposed mice also had abnormalities in glucose tolerance (males) and fat mass (females). HFCS exposure enriched carbohydrate, amino acid, long chain fatty acid and secondary bile acid metabolism at 6 weeks with changes in secondary bile metabolism at 6 and 30 weeks. Microbiome studies performed immediately before and after HFCS exposure identified profound shifts of microbial species in male mice only. In summary, short-term HFCS exposure during adolescence induces fatty liver, alters important metabolic pathways, some of which continue to be altered in adulthood, and changes the microbiome in a sex-specific manner.

Keywords: adolescence, high fructose corn syrup, metabolomics, microbiome

Introduction

Since 1970 the prevalence of obesity and its associated health problems, such as metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus, has risen at an alarming rate in children and adolescents (CDC, 2004) and as of 2015–2016, 18.5% of US children and adolescents were categorized as obese, reaching the highest prevalence in the past 16 years (Hales et al. 2017). This increase has been attributed to many causes, including diets with high fat and/or high sugar content. High sugar intake is a compelling potential aetiology, especially given that the rise in obesity over the past 30 years parallels an increase in the consumption of sweetened caloric beverages and processed foods with high sugar content (Periera, 2006; Harrington, 2008; Wang et al. 2008). According to data from the National Centre for Health Statistics in the CDC, Americans consumed 72 pounds of sugar per capita in 2016, a substantial increase fromthemid-1960s (Faruque et al. 2019). Recent estimates of fructose intake are 24 g each day and 40.5 g of refined sugar per day, which is 300% of the quantity of added sugar recommended by the CDC (Faruque et al. 2019). Adolescence is a particularly vulnerable period as children and young adults in this age group often consume high quantities of sugary drinks and processed food.

The composition of sweeteners consumed has also changed as sucrose (a glucose–fructose disaccharide) has been replaced by cheaper, ‘sweeter’ alternatives such as high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in a large percentage of food products (White, 2008; McConnell, 2017). HFCS use is pervasive; it sweetens caloric beverages, and is present in baked goods and many processed foods, yogurt and fruit juices (Bocarsly et al. 2010). HFCS exists in two forms, both of which are composed of free fructose and glucose molecules: HFCS-55 (55% fructose, 42% glucose, 3% higher saccharides), which comprises 60% of HFCS in the US food supply (Havel, 2005), and HFCS-42 (42% fructose, 53% glucose, 5% higher saccharides).

Fructose is metabolized in the liver and small intestine (Jang et al. 2018) and may be more lipogenic than glucose as fructolysis upregulates generation of acetyl CoA, which acts as a substrate for fatty acid synthesis when the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle is saturated, such as in an energy-replete state (Samuel, 2011). A growing body of evidence in rodent models raises the concern that free fructose is metabolized differently than fructose derived from sucrose (Ackerman et al. 2005; Armutcu et al. 2005; Jurgens et al. 2005; Bergheim et al. 2008; Howie et al. 2009; Light et al. 2009; Volynets et al. 2010; Vickers et al. 2011; Levy et al. 2015; Andres-Hernando et al. 2020; Tecz & Bence, 2020). In rodent models, excess fructose intake has been shown to promote weight gain (Havel, 2003; Jurgens et al. 2005; Light et al. 2009; Lustig, 2010), increased adiposity (Jurgens et al. 2005; Light et al. 2009), hepatic steatosis (Carmona & Freedland, 1989), and insulin resistance compared to sucrose (Light et al. 2009; Bocarsly et al. 2010). Human studies have also linked the metabolic effects of fructose to hypertriglyceridaemia (Havel, 2003; Teff et al. 2004; Chan et al. 2014) and increased visceral adiposity (Stanhope et al. 2009) with some sex-specific effects reported (Couchepin et al. 2008; Tran et al. 2010: Low et al. 2018). It has been suggested that HFCS ingestion increases hepatic de novo lipogenesis, resulting in increased triglyceride deposition in the liver, increased very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion and impaired insulin signalling (Stanhope & Havel, 2008).

Although the exact signalling pathways underlying these effects of HFCS consumption have not been clearly delineated, it is likely that HFCS-induced fatty liver disease and obesity result from abnormalities in multiple metabolic pathways. The gut microbiota play a role in the development of obesity (Ley et al. 2006), and recent work by Zhao et al. (2020) found that production of acetate by microbial metabolism of fructose contributes to hepatic lipogenesis. Thus, given the association between the gut microbiome and metabolic dysfunction, it is likely that host–microbe interactions contribute to HFCS-induced changes in lipogenesis and metabolic impairments through the production of bacterial metabolites (Jensen et al. 2018).

Based on the link between high consumption of HFCS by children and adolescents and the emerging epidemics of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity in adolescents and young adults, it is essential to evaluate the effects of HFCS consumption during this vulnerable developmental window. Therefore, we used a rodent model to determine the effects of HFCS during adolescence and whether HFCS-induced metabolic effects identified at 6 weeks were also present in adulthood well after the cessation of HFCS. Animal models are essential to understand the fundamental mechanisms of a disease process and provide a controlled experimental model to test a hypothesis. We hypothesized that HFCS would significantly impair metabolic signalling pathways in adolescent rodents with sex-specific effects on hepatic metabolism and that these impairments would be associated with shifts in the gut microbial composition, as well as in downstream metabolites.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Protocol no. 19–000773) and follow the guidelines from the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International.

All experiments conformed to the principals and regulations described by guidelines published in the Journal of Physiology (Grundy, 2015).

Animal care and experimental design

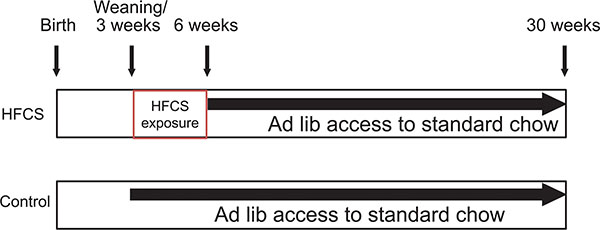

Female and male adult C57Bl/6J mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and maintained under controlled temperature (25°C) and light conditions (12 h light, 12 h dark cycles). After a week of acclimatization, mice were bred and pregnant females (n = 34) were allowed to spontaneously deliver. At 3 weeks of age offspring were weaned and randomly divided into experimental groups (HFCS and Control) and each litter was considered an n of 1 (Fig. 1). At weaning, all mice had ad libitum access to standard mouse chow (Mouse Diet 5015, PMI Nutrition International, St. Louis, MO, USA; 3.8% sugar, 18.9% protein, 11.2% fat, 3.8 kcal g−1) and water. A bottle containing a solution of HFCS (Nature’s Flavors High Fructose Corn Syrup Type 55, 50% solution in tap water, 1.5 kcal ml−1) was placed in each cage randomized to HFCS treatment. Mice were exposed to HFCS only during adolescence (from 3 to 6 weeks of life) while they were provided standard mouse chow diet (Mouse Diet 5015). Fresh HFCS-containing water was provided twice weekly and fresh food was provided once weekly. From 6 to 30 weeks of age, control and HFCS mice were fed standard mouse chow and had free access to water. The mice were weighed weekly. At 6 or 30 weeks of age animals were fasted for 6–8 h and then killed via CO2 inhalation, and liver and serum samples were obtained at that time. Animals that were sequentially studied throughout the study period were randomly selected at 3 weeks of age. After weaning, animals were housed singly in a cage and all cages were kept in the same animal care room on the same rack in the same position throughout the study period. Cages were changed by the animal care staff two or three times per week.

Figure 1.

Experimental design scheme

To determine if any of the phenotypic and metabolic effects of HFCS consumption were due to decreased food (chow) intake, a separate cohort of animals were pair-fed the same amount of chow. Controls had free access to water (n = 8 females and 10 males) and the HFCS group (n = 8 females and 10 males) had free access to the bottle of HFCS placed in each cage.

Solid food/HFCS consumption and caloric intake measurements

Solid food (chow) consumption was recorded once weekly and caloric intake from chow was calculated based on 3.8 kcal g−1 of chow. HFCS consumption was measured by subtracting the amount of solution remaining in the bottle from the volume initially given. Measurements of HFCS intake occurred twice weekly during the exposure period. Caloric intake from added HFCS was calculated as 1.5 kcal ml−1 for HFCS. Caloric intake is expressed as average kilocalories consumed per gram body weight per day and was measured until the end of the study period at 30 weeks of age.

Metabolic analyses

Glucose tolerance tests (GTTs) and body composition (NMR-LF50, Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA) were performed at 6 and 30 weeks of age (n = 6–7). Animals were fasted for 6–8 h, then 2 g kg−1 of glucose was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) and blood glucose was sequentially (0, 30, 60, 90, 120 min) measured in tail vein blood via clipping of the distal tail (Freestyle Glucometer, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA). Fasting serum leptin (ELISA, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and insulin levels (RIA, Millipore) were also measured in samples obtained from the tail vein. Liver was harvested at 6 and 30 weeks of age and snap frozen and stored at −80°C for measures of triglyceride content (Triglyceride Quantification Kit, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and metabolomic assays (see below).

Hepatic metabolomic profiling

At 6 weeks of age, male and female mice were fasted for 6–8 h, then killed, and liver samples were harvested for metabolomic profiling performed at Metabolon according to their standard sample preparation protocol (Metabolon Inc., Morrisville, NC, USA) (DeHaven et al. 2012; Evans et al. 2014; Goedeke et al. 2018; O’Neill et al. 2018). Samples were flash frozen and stored at −80°C prior to extraction (n = 8 per group). Sample preparation was carried out using the automated MicroLab STAR system (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA). The resulting extract was divided into two fractions, one for analysis by LC/MS/MS and one for analysis by GC/MS. Samples were placed briefly on a TurboVap (Zymark) to remove the organic solvent. Each sample was then frozen and dried under vacuum.

The LC/MS portion of the analysis was based on a Waters ACQUITY UPLC and a Thermo-Finnigan LTQ mass spectrometer, which consisted of an electrospray ionization (ESI) source and linear ion-trap (LIT) mass analyser. The sample extract was split into two aliquots, dried, and then reconstituted in acidic or basic LC-compatible solvents, each of which contained 11 or more injection standards at fixed concentrations. One aliquot was analysed using acidic positive ion optimized conditions and the other using basic negative ion optimized conditions in two independent injections using separate dedicated columns. Extracts reconstituted in acidic conditions were gradient eluted using water and methanol both containing 0.1% formic acid, while the basic extracts, which also used water/methanol, contained 6.5 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The MS analysis alternated between MS and data-dependent MS2 scans using dynamic exclusion.

The LC/MS portion of the platform was based on a Waters ACQUITY UPLC and a Thermo-Finnigan LTQ-FT mass spectrometer, which had an LIT front end and a Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) mass spectrometer backend. For ions with counts greater than 2 million, an accurate mass measurement could be performed. Accurate mass measurements could be made on the parent ion as well as fragments. The typical mass error was less than 5 ppm. Ions with less than 2 million counts require a greater amount of effort to characterize. Fragmentation spectra (MS/MS) were typically generated in a data-dependent manner, but if necessary, targeted MS/MS could be employed, such as in the case of lower level signals.

The samples destined for GC/MS analysis were re-dried under vacuum desiccation for a minimum of 24 h prior to being derivatized under dried nitrogen using bistrimethyl-silyl-triflouroacetamide (BSTFA). The GC column was 5% phenyl and the temperature ramp was from 40 to 300°C over a 16 min period. Samples were analysed on a Thermo-Finnigan Trace DSQ fast-scanning single-quadrupole mass spectrometer using electron impact ionization.

Compounds were identified by comparison to library entries of purified standards or recurrent unknown entities. Identification of known chemical entities was based on comparison to metabolomic library entries of purified standards.

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) were measured in liver homogenates from male and female offspring using the Parameter TBARS kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and normalized to total hepatic protein content.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

Total RNA was isolated from frozen liver (n = 8 each group) using RNeasy (Qiagen, Caldwell, NJ, USA) and only RNA with an integrity number >8 was used for gene expression analysis using the Agilent Bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA, USA). cDNA was generated using the Biorad iSCRIPT kit. Real-time PCR was performed using a TaqMan Gene expression assay in an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System. Expression relative to control was calculated using the comparative CT method. Data were normalized to Rpl19 and Beta actin, standard housekeeping genes whose expression was not altered by age or experimental condition. Gene transcripts in each sample were determined by the ΔΔCT method. For each sample, the threshold cycle (CT) was measured and normalized to the average of the housekeeping gene (ΔCT). The fold change of mRNA in the unknown sample relative to the control group was determined by 2-ΔΔCT. TaqMan (Applied Biosystems, Wilmington, DE, USA) primers were used for the following genes: ACC, DGAT, FAS, ChREBP, SCD, SREBP1, PPARα, CPT, Rpl19 and Beta actin.

Microbiome analyses

16srRNA gene sequencing.

At 3 weeks of age, the animals were weaned and placed in separate cages (one animal per cage). Twenty-four hours later, HFCS was started and faecal pellets were collected 12 h after HFCS exposure was started and again at 6 weeks of age (after 3 weeks of exposure, n = 6–8). Genomic DNA was extracted and amplification of the V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene was performed as previously described (Bartram et al. 2011; Whelan et al. 2014). Briefly, each faecal pellet was mechanically homogenized and enzymatically lysed before phenol–chloroform–isoamyl DNA extraction. Amplification of the V3 region (341F/518R) was performed using barcode-adapted reverse primers. Each reaction contained 5 pmol of primer, 200 mm of dNTPs, 1.5 μl 50 mm MgCl2, 2 μl of 10 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin (irradiated with a transilluminator to eliminate contaminating DNA) and 0.25 μl Taq polymerase (Life Technologies, Canada) for a total reaction volume of 50 μl. PCR products were purified by gel electrophoresis and subsequently sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 150 bp) at the Farncombe Genomics Facility (McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada).

Processing and analysis of sequencing data.

Resultant FASTQ files were processed using a custom in-house pipeline (Whelan et al., 2014). Reads exceeding the length of the 16S rRNA V3 region were trimmed using Cutadapt (Martin, 2011), and paired-end reads were aligned using PANDASeq (Masella et al. 2012). Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were generated using DADA2 (Callahan et al. 2016) and taxonomy was assigned using the RDP Classifier (Ribosomal Database Project, RRID:SCR_006633) against the Silva 132 reference database. Non-bacterial ASVs were removed by pruning taxa belonging to the kingdom Eukaryota, an unknown phylum, the family Mitochondria, or the order Chloroplast.

Statistical analysis

Metabolomic data were analysed using two-way ANOVA, where sex and treatment were factors and corrected for multiple testing using the false discovery rate (FDR; significance threshold set at a q-value < 0.05). The statistical analysis was performed using the program ‘R’ (http://cran.r-project.org/).The sample size represents the number of litters analysed where a randomly chosen male and female were analysed from each litter. Power analysis was used to calculate sample size and we approximated a 25% change with a standard deviation of 20%, 80% power and a significance level α of 0.05. All other data were analysed using unpaired two-tailed Student t tests or Mann–Whitney testing for non-parametric data for two comparisons. Multiple group comparisons were done using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison testing or Kruskal–Wallis tests followed by Dunn’s testing for non-parametric data. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Sequencing analysis.

Analysis of sequencing data was performed in R (R Project for Statistical Computing, RRID:SCR_001905). ASVs were generated using DADA2 (Callahan et al. 2016) and taxonomy was assigned using the RDP Classifier (Ribosomal Database Project, RRID:SCR_006633) against the Silva 132 reference database. Alpha diversity measures of rarified ASV data were calculated using the Shannon diversity index (phyloseq, RRID:SCR_013080) and analysed by linear mixed model with treatment (HFCS vs. control) and day (3 weeks vs. 6 weeks) as fixed effects and mouse ID as a random effect. Beta diversity of normalized (total sum scaled) ASV counts was calculated using the Bray Curtis dissimilarity metric and visualized via principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) ordination (ggplot2, RRID:SCR_014601). Whole community differences across groups were analysed using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) in the adonis command (vegan; RRID:SCR_011950). DESeq2 (RRID:SCR_015687) was used to identify genera which differed significantly between groups (significance threshold set P < 0.01 after adjustment for multiple testing via DESeq2’s implementation of the Benjamini–Hochberg multiple testing adjustment procedure) and visualized using ggplot2.

Results

Weight gain and body fat content

Total caloric intake, per gram of body weight, was similar between groups in both males and females during the exposure period, as we have previously reported (Clayton et al. 2015). In addition, intake of HFCS, per gram of body weight, did not differ between males and females. Total caloric intake for males averaged 0.59 ± 0.01 vs. 0.55 ± 0.01 kcal g−1 body weight/day and in females was 0.61 ± 0.02 vs. 0.67 ± 0.02 kcal g−1 body weight/day (HFCS vs. Controls respectively). Approximately 40% of the total caloric intake in the HFCS-exposed animals was from HFCS during the exposure period (0.245 ± 0.005 kcal g−1 body weight/day, and in females was 0.231 ± 0.004 kcal g−1 body weight/day). Throughout the remainder of the study period (after exposure ended) caloric consumption averaged 0.39 ± 0.01 kcal g−1 for females and 0.46 ± 0.01 kcal g−1 body weight/day for males in both study groups.

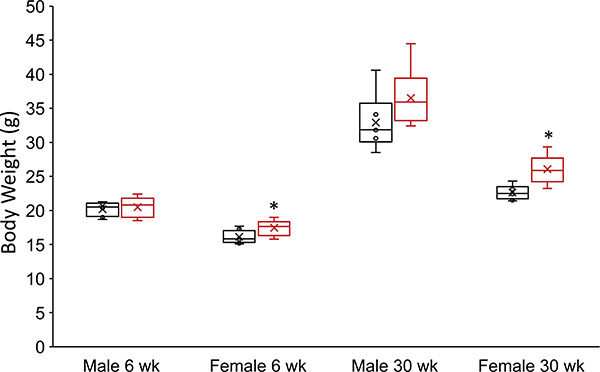

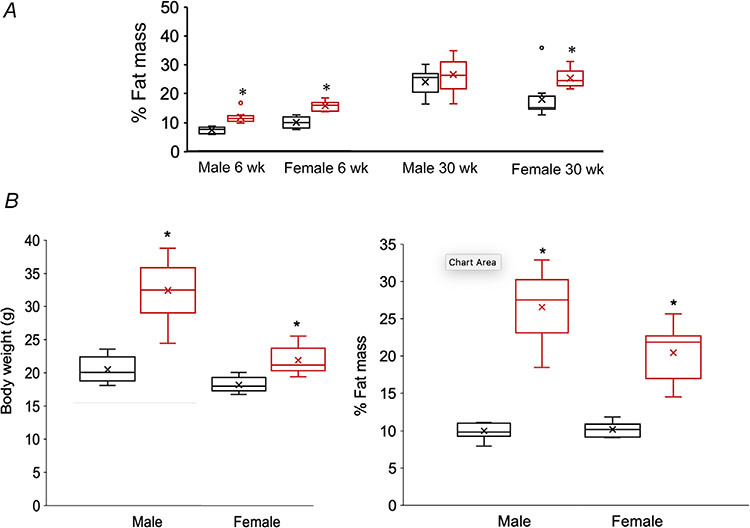

At 6 weeks of age both male and female HFCS mice had significantly increased percentage fat mass, but only females weighed more than their control counterparts (Figs 2 and 3A). This increase in percentage fat mass was associated with significantly elevated levels of serum insulin, leptin and adiponectin in males and only leptin in females (Table 1). At 30 weeks of age, weight and percentage fat mass remained significantly elevated in females, but not in males (Figs 2 and 3A). Insulin and adiponectin remained high in males and leptin was elevated in females (Table 1).

Figure 2. Weight at 6 and 30 weeks of age.

Males 6 weeks: control n = 14, HFCS n = 14 (P = 0.647) and females 6 weeks: control n = 13, HFCS n = 13 weeks (P = 0.022); males 30 weeks: control n = 8, HFCS n = 8 (P = 0.153) and females 30 weeks: control n = 8, HFCS n = 8 (P = 0.0017). Data analysed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. *Statistically significant difference HFCS vs. control.

Figure 3. Percent fat mass at 6 and 30 weeks of age in Control and HFCS mice.

A, box plots of percentage body fat measurements at 6 and 30 weeks of age in Control (black boxes) and HFCS (red boxes). At 6 weeks: males: control n = 8, HFCS n = 8, P = 0.0001; and females: control n = 8, HFCS n = 8, P = 2.301E-05. At 30 weeks: males: control n = 7, HFCS n = 7, P = 0.394; and females: control n = 8, HFCS n = 8, P = 0.0234. B, box plots of body weight and body fat measurements in pair fed animals at 14 weeks of age in control (black boxes) and HFCS (red boxes) in males: control n = 9, HFCS n = 10, P = 2.313E-07 for weight and P = 4.333E-09 for body fat; females: control n = 6, HFCS n = 5, P = 0.000327 for weight and P = 3.741E-07. Data were analysed by an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. An ‘x’ within a box represents the mean. *Statistically significant difference between groups.

Table 1.

Fasting insulin, leptin, adiponectin levels in HFCS exposed animals

| 6 weeks |

30 weeks |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFCS |

Control |

HFCS |

Control |

|||||

| Male N = 12 |

Female N = 12 |

Male N = 10 |

Female N = 12 |

Male N = 10 |

Female N = 12 |

Male N = 11 |

Female N = 12 |

|

| Insulin (ng ml−1) | 1.4 ± 1.0 P = 0.0383 |

0.3 ± 0.2 P = 0.1212 |

0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.6 P = 0.0008 |

0.5 ± 0.2 P = 0.2687 |

1.1 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.2 |

| Leptin (ng ml−1) | 22.0 ± 10.6 P = 8.59E-05 |

2.9 ± 0.9 P = 0.0043 |

3.7 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 7.3 ± 1.9 P = 0.1081 |

7.1 ± 0.61 P=2.44E-08 |

5.9 ± 1.9 | 4.4 ± 0.7 |

| Adiponectin (μg ml−1) | 27.0 ± 4.7 P = 7.82E-06 |

32.1 ± 3.4 P = 0.5120 |

17.5 ± 2.4 | 39.3 ± 10.9 | 35.6 ± 6.4 P = 0.0002 |

51.6 ± 5.1 P = 0.4065 |

23.3 ± 5.5 | 50.1 ± 3.9 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Data were analysed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test.

To determine if any of the phenotypic and metabolic effects of HFCS consumption were due to decreased food (chow) intake, a separate cohort of animals (n = 8 males; n = 10 females) were pair-fed the same amount of chow. When calories from chow were kept the same in the groups, the HFCS animals consumed significantly more calories and averaged 0.6 kcal g−1 of body weight/day in males and females vs. 0.42 kcal g−1 body weight/day in male and female control mice (two-way ANOVA, P = 0.0003). Similar to the first study, HFCS consumption in the pair-fed animals resulted in increased weight and body fat content (Fig. 3B), and glucose intolerance at 14 weeks of age (Fig. 4C).

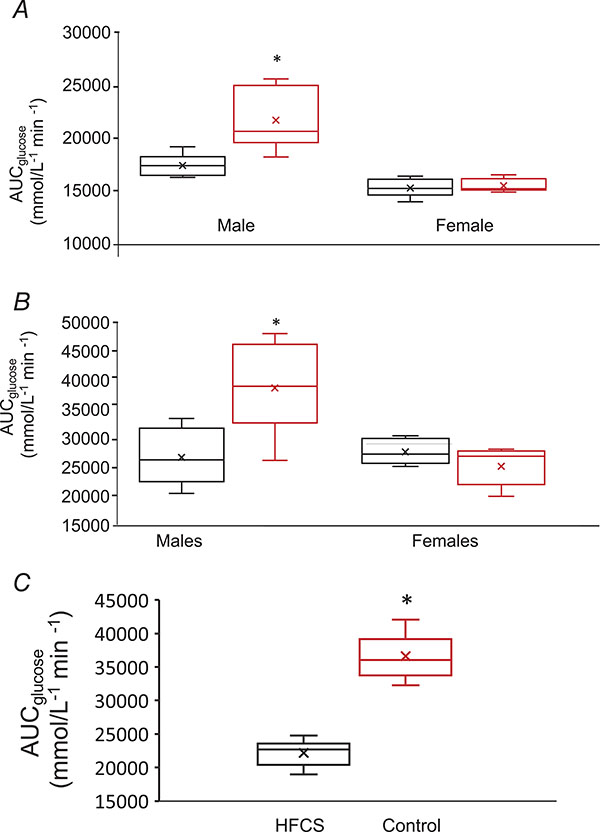

Figure 4. Glucose tolerance at 6 weeks (A) and 30 weeks (B) in Control and HFCS.

Box plots of AUCglucose in males, control n = 7 male HFCS n = 6, P = 0.0027 at 6 weeks and P = 0.000104 at 30 weeks; females control n = 7, HFCS n = 7, P = 0.594 at 6 weeks and P = 0.0962 at 30 weeks. C, glucose tolerance in pair-fed animals at 14 weeks in control and HFCS. Box plots of AUCglucose in males, control n = 9 male HFCS n = 12, P = 4.2040E-10. Data are expressed as means ± SD. Data were analysed by an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. An ‘x’ within a box represents the mean. *Statistically significant difference HFCS vs. control.

Glucose tolerance

HFCS-exposed males showed significantly impaired glucose tolerance compared to controls at 6 and 30 weeks of age (Fig. 4A and B). Despite higher body weight and fat mass, HFCS females did not show signs of abnormal glucose homeostasis compared to controls at 6 or 30 weeks (Fig. 4A and B). HFCS intake resulted in higher serum insulin levels in males at 6 and 30 weeks of age, but not in females at any age, suggesting that fasting hyperinsulinaemia is sex-specific and not correlated with increased body fat content (Table 1). Similarly, glucose tolerance was significantly impaired in male pair-fed animals at 14–16 weeks of age; females were unable to be assessed due to unexpected death unrelated to experimental conditions (Fig. 4C).

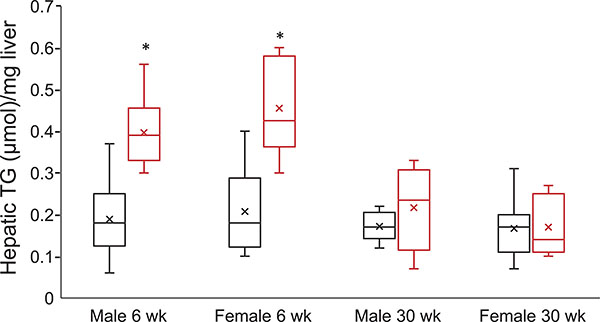

Hepatic lipid content

At 6 weeks of age, hepatic triglyceride content was significantly increased in both male and female HFCS-fed animals compared to controls, with a greater degree of increase observed in the HFCS females compared to the males (Fig. 5). However, by 30 weeks of age, triglyceride content was similar in all groups (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Box plots of hepatic triglyceride (TG) content in Control (black boxes) and HFCS (red boxes).

Males (control n = 8, HFCS n = 7) P = 0.000135 and females at 6 weeks (control n = 8, HFCS n = 8) P = 0.000429. Males (control n = 6, HFCS n = 7) P = 0.324 and females at 30 weeks (control n = 8, HFCS n = 8) P = 0.944. Data were analysed by an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. An ‘x’ within a box represents the mean. *Statistically significant difference HFCS vs. control.

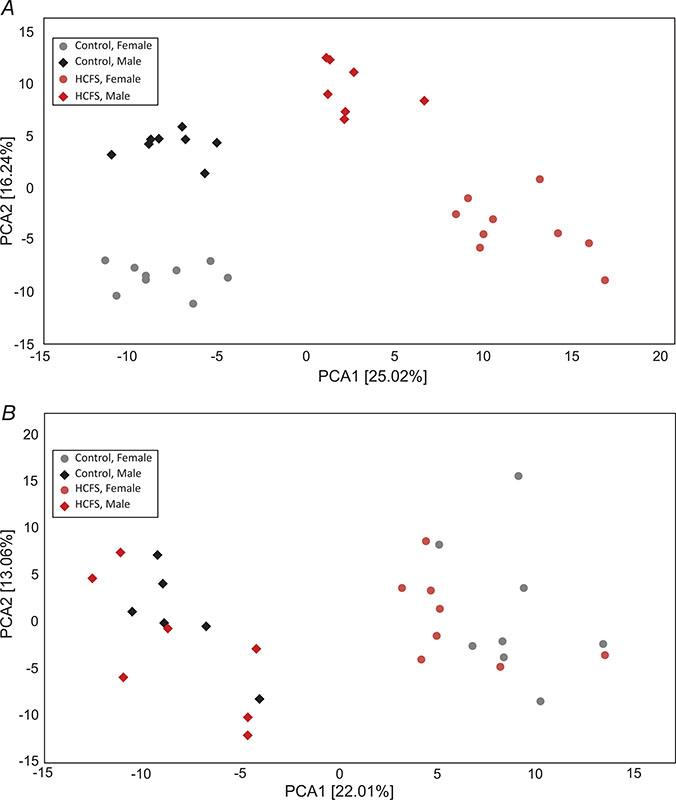

Hepatic analysis and global metabolomic profiling

As hepatic triglyceride levels were elevated in HFCS animals and fructose is known to alter hepatic metabolism (Herman & Samuel, 2016), we performed metabolomic analyses in liver at 6 and 30 weeks of age, to gain insight into potential mechanisms and identify additional metabolic pathways that might be altered. Global metabolomic profiles of liver in 6-week-old mice identified 202 metabolites that differed (q < 0.05 vs. control) between the treatment groups from a total of 325 metabolites contained within the Metabolon library (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1 for review only). These results demonstrate that a diet supplemented with HFCS had a profound effect on the global liver biochemical profiles with approximately 75% of the total metabolites measured demonstrating a significant difference between HFCS and controls in males and females at 6 weeks of age. Although many of these metabolites were altered in both sexes, the changes observed in female mice were often larger, and differential changes between males and females were observed for a number of metabolites (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1 for review only). By 30 weeks of age, there were far fewer differences between groups and only 52 metabolites significantly differed (q < 0.05) between HFCS and controls (Table 2, Supplemental Table 2 for review only). Again, there was a marked sex difference and, at this age, more metabolites differed between the sexes than between the experimental groups. Principal component analysis (PCA) showed a clear segregation according to treatment and sex at 6 weeks of age (Fig. 6A), but only for sex (not treatment) at 30 weeks of age (Fig. 6B).

Table 2.

Metabolites showing a significant treatment and or a sex effect in HFCS exposed animals

| 6 weeks |

30 weeks |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of biochemicals | Biochemicals | Total no. of biochemicals | Biochemicals | |

| Female | 187 | 59↑ 128↓ | 23 | 9↑ 14↓ |

| Male | 140 | 71↑ 69↓ | 30 | 26↑ 4↓ |

| Number of biochemicals | ||||

| Sugar effect | 202 | 52 | ||

| Sex effect | 159 | 145 | ||

| Sugar × Sex interaction | 87 | 27 | ||

Significance determined by two-way ANOVA, where sex and treatment were factors and corrected for multiple testing using the FDR. N = 8 per group.

Figure 6. Principal component analysis of metabolites.

A, 6 weeks of age in liver from control chow and HFCS-fed male and female mice; B, 30 weeks of age. N = 8 each group at each age.

We used Random Forest classification to identify metabolites which were predicted to have the greatest influence on distinguishing between the experimental groups (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 for review only). The metabolic pathways that were most affected at 6 weeks of age included those associated with fatty acid synthesis, bile acids, glucose metabolism, amino acid metabolism and antioxidant biosynthesis. At 30 weeks of age, the most affected pathways were primarily those involved with bile acid metabolism, fatty acid synthesis and amino acid metabolism (Supplementary Figures 3 and 4 for review only).

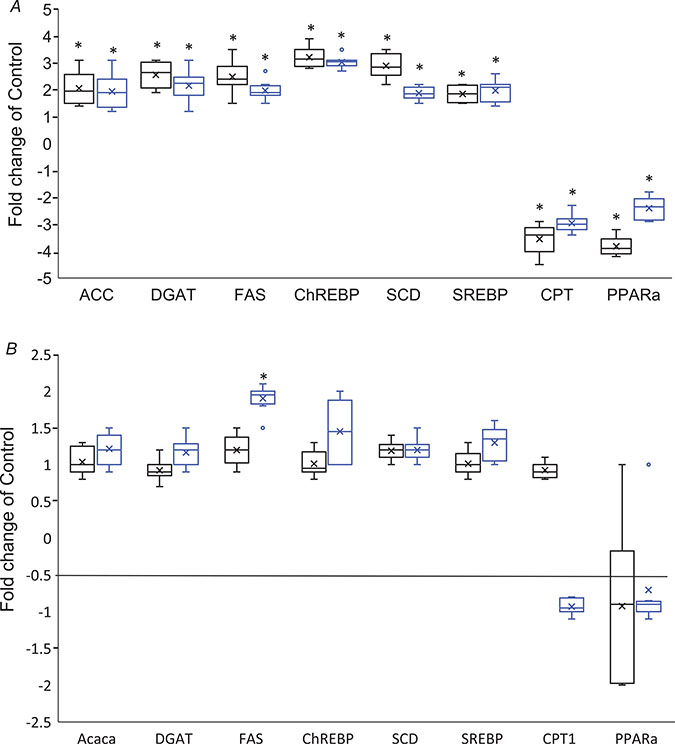

Lipids.

Fructose can contribute to hepatic de novo lipogenesis and steatosis via production of glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P), acetyl-CoA, and NADPH by glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway (Lim et al. 2010). Indeed, levels of G3P and multiple free fatty acids were significantly increased with HFCS ingestion in 6-week-old males and females, as was citrate, which is involved in export of acetyl-CoA from the mitochondria for fatty acid synthesis (Table 3). Further evidence that hepatic de novo lipogenesis was enhanced by HFCS exposure was our finding that mRNA levels of key enzymes mediating lipogenesis (ACC, DGAT, FAS, ChREBP, SCD and Srebp1) and fatty acid oxidation (PPARα and Cpt1) were significantly altered in HFCS male (P = 0.024, 0.003, 0.012, 0.0009, 0.001, 0.023, 0.0016 and 0.0008 respectively) and female liver at 6 weeks of age (P = 0.012. 0.028, 0.0001, 8.12E-05, 0.0001, 0.025, 0.0002 and 0.001 respectively) (Fig. 7A). In addition, a number of carnitine metabolites were significantly decreased in HFCS females and males, consistent with depressed fatty acid oxidation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Fold change in lipid metabolites in HFCS-exposed 6-week-old animals

| Female | q value | Male | q value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential fatty acid | Linoleate (18:2n6) | 1.13 | 0.0557 | 0.92 | 0.1779 |

| Linolenate [alpha or gamma; (18:3n3 or 6)] | 0.84 | 0.108 | 0.68 | 0.0199 | |

| Dihomo-linolenate (20:3n3 or n6) | 1.11 | 0.04 | 1.47 | 2.46E-05 | |

| Eicosapentaenoate (EPA; 20:5n3) | 0.75 | 0.0736 | 0.71 | 0.0262 | |

| Docosapentaenoate (n3 DPA; 22:5n3) | 0.36 | 1.06E-06 | 0.47 | 0.0001 | |

| Docosapentaenoate (n6 DPA; 22:5n6) | 0.36 | 6.78E-08 | 1.14 | 0.2672 | |

| Eicosanoids | 0.74 | 0.0012 | 0.86 | 0.0531 | |

| Medium chain fatty acid | Caproate (6:0) | 0.89 | 0.0658 | 1.17 | 0.0685 |

| Heptanoate (7:0) | 0.74 | 0.0212 | 0.66 | 0.0161 | |

| Caprylate (8:0) | 1.04 | 0.2307 | 0.96 | 0.3424 | |

| Pelargonate (9:0) | 1.04 | 0.1564 | 1.12 | 0.0995 | |

| Caprate (10:0) | 0.87 | 0.017 | 0.93 | 0.1224 | |

| Laurate (12:0) | 0.91 | 0.093 | 0.93 | 0.1529 | |

| Long chain fatty acid | Myristate (14:0) | 2.19 | 1.90E-07 | 1.37 | 0.0125 |

| Myristoleate (14:1n5) | 2.14 | 1.66E-06 | 1.52 | 0.0033 | |

| Palmitate (16:0) | 1.46 | 0.0002 | 1.14 | 0.1154 | |

| Palmitoleate (16:1n7) | 4.21 | 1.74E-09 | 2.31 | 0.0001 | |

| Margarate (17:0) | 0.82 | 0.0018 | 0.84 | 0.0092 | |

| 10-Heptadecenoate (17:1n7) | 2.6 | 2.89E-08 | 1.68 | 0.0006 | |

| Stearate (18:0) | 1.28 | 0.0099 | 1.16 | 0.1149 | |

| Oleate (18:1n9) | 3.24 | 2.37E-12 | 1.87 | 1.42E-06 | |

| cis-Vaccenate (18:1n7) | 3.25 | 1.33E-08 | 2.36 | 2.20E-05 | |

| stearidonate (18:4n3) | 0.55 | 0.0056 | 0.51 | 0.0044 | |

| Nonadecanoate (19:0) | 0.69 | 1.53E-05 | 0.63 | 6.44E-06 | |

| 10-Nonadecenoate (19:1n9) | 2.63 | 3.23E-09 | 1.86 | 2.59E-05 | |

| Eicosenoate (20:1n9 or 11) | 5.54 | 1.00E-15 | 2.24 | 5.29E-08 | |

| Dihomo-linoleate (20:2n6) | 1.35 | 0.0008 | 1.32 | 0.0069 | |

| Arachidonate (20:4n6) | 0.81 | 0.0011 | 0.98 | 0.2902 | |

| Erucate (22:1n9) | 1.74 | 0.0002 | 1.36 | 0.0593 | |

| Docosadienoate (22:2n6) | 1.06 | 0.1262 | 0.89 | 0.0409 | |

| Docosatrienoate (22:3n3) | 2.07 | 3.70E-05 | 4.31 | 2.71E-08 | |

| Adrenate (22:4n6) | 0.55 | 5.35E-07 | 0.69 | 0.0006 | |

| Fatty acid, monohydroxy | 3-Hydroxydecanoate | 0.93 | 0.1841 | 1.01 | 0.3337 |

| 16-Hydroxypalmitate | 0.75 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.3863 | |

| 2-Hydroxystearate | 0.58 | 0.0009 | 0.9 | 0.1836 | |

| 13-HODE + 9-HODE | 1.12 | 0.243 | 1.1 | 0.2682 | |

| Fatty acid, dicarboxylate | 2-Hydroxyglutarate | 1 | 0.2491 | 1.27 | 0.0033 |

| Hexadecanedioate | 1.14 | 0.0543 | 1.12 | 0.1015 | |

| Fatty acid, branched | 17-Methylstearate | 1.33 | 0.0014 | 0.89 | 0.0929 |

| Eicosanoid | 6-Keto prostaglandin F1alpha | 0.8 | 0.0693 | 1.47 | 0.085 |

| Endocannabinoid | Palmitoyl ethanolamide | 1.05 | 0.1627 | 1.26 | 0.0142 |

| Fatty acid metabolism (also BCAA metabolism) | Propionylcarnitine | 0.26 | 1.21E-05 | 0.81 | 0.1997 |

| Butyrylglycine | 1.59 | 0.0617 | 0.92 | 0.2977 | |

| Fatty acid metabolism | Hexanoylglycine | 1.06 | 0.1793 | 0.86 | 0.1801 |

| Carnitine metabolism | Deoxycarnitine | 0.7 | 0.0006 | 0.62 | 0.0002 |

| Carnitine | 0.85 | 0.0105 | 1.03 | 0.3307 | |

| 3-Dehydrocarnitine | 0.49 | 9.90E-08 | 0.72 | 0.0019 | |

| Acetylcarnitine | 0.66 | 0.001 | 0.99 | 0.3433 |

Significance determined by two-way ANOVA, where sex and treatment were factors and corrected for multiple testing using the FDR. N = 8 per group.

Figure 7. Box plot changes in expression of genes regulating lipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation at (A) 6 weeks and (B) 30 weeks in control and HFCS males (black boxes) and females (blue boxes).

N = 8 per sex, per age, per group. Data are expressed as fold-change. Data were analysed by an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. An ‘x’ within a box represents the mean. *Statistically significant difference HFCS vs. control.

The majority of the free fatty acids altered by HFCS exposure were monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) that are generated from dietary and endogenous saturated fatty acids (SFAs) by the enzyme stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) and mRNA levels of SCD were significantly increased in 6-week-old male and female HFCS groups (Fig. 7A).However, only FAS mRNA levels were increased in females at 30 weeks of age (ACC: 0.21, 0.79; DGAT: 0.40, 0.46, FAS 0.11, 1.55 E-05; ChREBP: 0.58, 0.81; SCD: 0.61, 0.38; Srebp1: 0.61, 0.38; CPT: 0.37, 0.59; PPARα: 0.80, 0.66) (Fig. 7B). Notably, levels of the SFAs palmitate and stearate were significantly elevated in 6-week-old females but not males with HFCS ingestion, and the increases in MUFA levels were greater in HFCS females than in HFCS males as compared to controls (Table 3). In contrast to MUFAs, several ω−6 and ω−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) that are synthesized from the diet-derived fatty acids linoleate and α-linolenate were significantly reduced with HFCS intake (Table 3). These changes include significantly decreased levels of steridonate, eicosapentaenoate (EPA), docosapentaenoate (DPA) and adrenate in male and female HFCS-exposed mice. These changes may reflect increased oxidation and subsequent conjugation of PUFAs as the result of increased oxidative species in association with HFCS (see below). Interestingly, arachidonate, from which pro-inflammatory eicosanoids are synthesized, was reduced in females, but not males in the HFCS group. These sex-specific differences in metabolism and gene expression may play an important role in the sex-specific disease manifestations resulting from dietary intake of HFCS.

Despite similar levels of hepatic triglyceride content at 30 weeks of age in HFCS and control animals (Fig. 5), several long-chain free fatty acids, including palmitate, oleate and stearidonate, were elevated in females, but not males, exposed to HFCS (Table 4). Glycerol and glycerol-3-phosphate levels were also elevated (1.31- and 1.39-fold increase, respectively), but the changes did not quite reach statistical significance (Table 4) in HFCS females, suggesting that increases in de novo lipogenesis that were present at 6 weeks remained elevated at 30 weeks. However, as increased lipogenesis was not associated with triglyceride deposition in the liver, fatty acid trafficking out of the liver may be increased.

Table 4.

Fold change in lipid metabolites in HFCS-exposed 30-week-old animals

| Female | q value | Male | q value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential fatty acid | Linoleate (18:2n6) | 1.37 | 0.0453 | 1.08 | 0.8896 |

| Linolenate [alpha or gamma; (18:3n3 or 6)] | 1.64 | 0.0562 | 0.93 | 0.8794 | |

| Dihomo-linolenate (20:3n3 or n6) | 1.22 | 0.1051 | 1.01 | 0.9107 | |

| Eicosapentaenoate (EPA; 20:5n3) | 1.49 | 0.0583 | 0.88 | 0.8144 | |

| Docosapentaenoate (n3 DPA; 22:5n3) | 1.47 | 0.0931 | 0.89 | 0.8144 | |

| Docosapentaenoate (n6 DPA; 22:5n6) | 0.9 | 0.3702 | 0.94 | 0.8098 | |

| Docosahexaenoate (DHA; 22:6n3) | 1.1 | 0.1744 | 1.01 | 0.9043 | |

| Medium chain fatty acid | Caproate (6:0) | 1.02 | 0.8949 | 0.79 | 0.7536 |

| Long chain fatty acid | Myristate (14:0) | 1.39 | 0.0927 | 1.2 | 0.8713 |

| Myristoleate (14:1n5) | 1.33 | 0.3186 | 1.39 | 0.6653 | |

| Pentadecanoate (15:0) | 1.21 | 0.4386 | 1.13 | 0.8144 | |

| Palmitate (16:0) | 1.27 | 0.05 | 1.09 | 0.8519 | |

| Palmitoleate (16:1n7) | 1.51 | 0.0478 | 1.25 | 0.8519 | |

| Margarate (17:0) | 1.38 | 0.0405 | 0.92 | 0.8144 | |

| 10-Heptadecenoate (17:1n7) | 1.58 | 0.0397 | 1.1 | 0.9043 | |

| Stearate (18:0) | 1.15 | 0.0628 | 0.97 | 0.8713 | |

| Oleate (18:1n9) | 1.5 | 0.077 | 1.34 | 0.7391 | |

| cis-Vaccenate (18:1n7) | 1.01 | 0.8225 | 1.59 | 0.4047 | |

| Stearidonate (18:4n3) | 1.88 | 0.115 | 0.72 | 0.6859 | |

| Nonadecanoate (19:0) | 1.06 | 0.5027 | 0.9 | 0.6091 | |

| 10-Nonadecenoate (19:1n9) | 1.38 | 0.081 | 1.16 | 0.8794 | |

| Eicosenoate (20:1n9 or 11) | 1.55 | 0.0531 | 1.13 | 0.9043 | |

| Dihomo-linoleate (20:2n6) | 1.36 | 0.0959 | 1.06 | 0.931 | |

| Mead acid (20:3n9) | 1.24 | 0.1171 | 1.06 | 0.9043 | |

| Arachidonate (20:4n6) | 1.07 | 0.2503 | 1.09 | 0.6653 | |

| Erucate (22:1n9) | 0.97 | 0.7327 | 0.89 | 0.6886 | |

| Docosadienoate (22:2n6) | 0.93 | 0.6197 | 0.95 | 0.888 | |

| Adrenate (22:4n6) | 1.13 | 0.5555 | 0.84 | 0.6653 | |

| Fatty acid, monohydroxy | 16-Hydroxypalmitate | 0.89 | 0.3447 | 0.99 | 0.9043 |

| 2-Hydroxystearate | 1.14 | 0.2191 | 0.99 | 0.9043 | |

| 13-HODE + 9-HODE | 1.4 | 0.0737 | 0.81 | 0.6653 | |

| Fatty acid, dicarboxylate | 2-Hydroxyglutarate | 0.89 | 0.6562 | 0.97 | 0.8794 |

| Hexadecanedioate | 0.9 | 0.5997 | 1.08 | 0.9115 | |

| Fatty acid, branched | 15-Methylpalmitate (isobar with 2-methylpalmitate) | 1.13 | 0.3325 | 1 | 0.9043 |

| 17-Methylstearate | 1.33 | 0.0029 | 0.89 | 0.6653 | |

| Eicosanoid | 12-HETE | 1.05 | 0.5579 | 1.15 | 0.6653 |

| Endocannabinoid | Palmitoyl ethanolamide | 1.16 | 0.2486 | 0.83 | 0.6653 |

| N-Palmitoyl taurine | 1.09 | 0.5931 | 1.62 | 0.4646 | |

| Fatty acid metabolism (also BCAA metabolism) | Propionylcarnitine | 0.83 | 0.2304 | 0.95 | 0.8896 |

| Hydroxybutyrylcarnitin | 1.46 | 0.0505 | 1.15 | 0.8506 | |

| Butyrylglycine | 0.5 | 0.018 | 0.96 | 0.9043 | |

| Fatty acid synthesis | Malonylcarnitine | 0.96 | 0.8363 | 1.03 | 0.9043 |

| Carnitine metabolism | Deoxycarnitine | 0.77 | 0.0422 | 0.77 | 0.4402 |

| Carnitine | 1.15 | 0.039 | 1.11 | 0.6091 | |

| 3-Dehydrocarnitine | 1.11 | 0.3026 | 1.32 | 0.1607 | |

| Acetylcarnitine | 1.02 | 0.8488 | 0.89 | 0.8029 | |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | Choline phosphate | 0.95 | 0.59 | 1.22 | 0.6653 |

| Ethanolamine | 0.94 | 0.8288 | 1.07 | 0.8794 | |

| Phosphoethanolamine | 0.57 | 0.0207 | 1.44 | 0.5858 | |

| Glycerol | 1.31 | 0.0722 | 1.19 | 0.7014 | |

| Choline | 0.97 | 0.5877 | 1.01 | 0.9043 | |

| Glycerol 3-phosphate (G3P) | 1.39 | 0.0571 | 0.86 | 0.8144 | |

| Glycerophosphorylcholine (GPC) | 0.97 | 0.8181 | 0.75 | 0.6091 | |

| Cytidine 5′-diphosphocholine | 1.06 | 0.5071 | 1.05 | 0.8879 |

Significance determined by two-way ANOVA, where sex and treatment were factors and corrected for multiple testing using the FDR. N = 8 per group.

Bile acids.

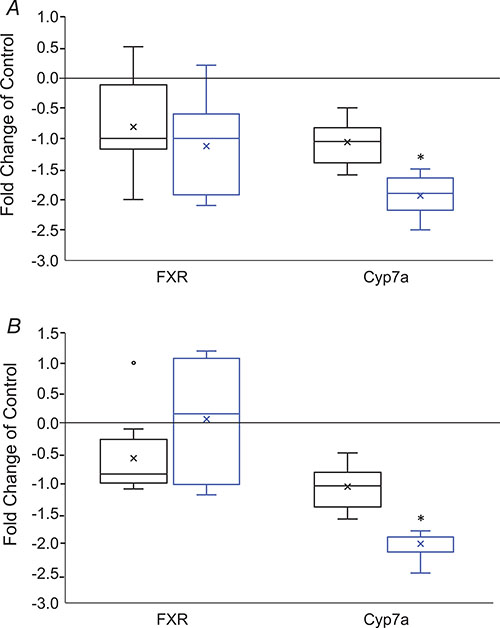

Bile acids, which play a central role in hepatic lipid metabolism as well as obesity, were markedly altered in HFCS females, but not males at 6 weeks of age. Both primary (cholate, chenodeoxycholate) and secondary bile acids (6-beta-hydroxylithocholate, beta-muricholate and alpha-muricholate) were reduced (Table 5). The decrease in secondary bile acids was more pronounced than primary bile acids, consistent with the notion that gut microbial-mediated deconjugation and dehydroxylation processes may be altered by consumption of HFCS in females (see below). In HFCS females, but not males, we observed significantly reduced mRNA levels of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (Cyp7a1) (females, P = 0.00747; males, P = 0.0555) (Fig. 8A), the rate-limiting enzyme for bile acid production. In contrast, expression of FXR, a key nuclear receptor that plays an important role in lipoprotein metabolism (Kliewer & Mangelsdorf, 2015), was unaltered in HFCS females (P = 0.247) and HFCS males (P = 0.438) (Fig. 8A).

Table 5.

Fold change in bile acids in HFCS-exposed 6-week-old animals

| Female | q value | Male | q value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholate | 0.57 | 0.0636 | 0.87 | 0.3307 |

| Taurocholate | 1.18 | 0.2496 | 0.92 | 0.3505 |

| Taurohyocholate | 0.97 | 0.2138 | 1.17 | 0.3362 |

| Chenodeoxycholate | 0.47 | 0.0058 | 0.8 | 0.2779 |

| Taurolithocholate | 0.78 | 0.0971 | 1.09 | 0.2844 |

| 6-Beta-hydroxylithocholate | 0.48 | 0.006 | 0.8 | 0.2127 |

| Beta-muricholate | 0.53 | 0.0084 | 0.56 | 0.058 |

| Alpha-muricholate | 0.42 | 0.0097 | 0.61 | 0.1405 |

| Tauroursodeoxycholate | 2.24 | 0.019 | 1.3 | 0.2304 |

| Tauro(alpha + beta)muricholate | 1.62 | 0.1123 | 1.15 | 0.3576 |

Significance determined by two-way ANOVA, where sex and treatment were factors and corrected for multiple testing using the FDR. N = 8 per group.

Figure 8. Box plot changes in expression of genes regulating bile acid metabolism at (A) 6 weeks and (B) 30 weeks in control and HFCS males (black boxes) and females (blue boxes).

N = 8 per sex, per age, per group. Data are expressed as fold-change over control. Data were log transformed and analysed by Mann-Whitney testing for non-parametric data for two comparisons. An ‘x’ within a box represents the mean. *Statistically significant difference HFCS vs. control.

Surprisingly, at 30 weeks of age, hepatic bile acid levels were further reduced in HFCS females compared to controls and both primary and secondary bile acids were decreased. In addition, in contrast to 6-week-old HFCS females, tauro-conjugated bile acids were markedly decreased in HFCS females at 30 weeks of age (Table 6). There were no changes in bile acids in HFCS males, consistent with our observations at 6 weeks of age. Interestingly, expression of Cyp7a remained reduced in HFCS females (P = 0.009), but expression of FXR was unchanged (P = 0.68) (Fig. 8B).

Table 6.

Fold change in bile acids in HFCS-exposed 30-week-old animals

| Female | q value | Male | q value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholate | 0.43 | 0.0175 | 1.09 | 0.7572 |

| Taurocholate | 0.53 | 0.0291 | 1.15 | 0.6875 |

| Taurochenodeoxycholate | 0.59 | 0.015 | 1.19 | 0.7268 |

| Ursodeoxycholate | 0.62 | 0.0685 | 1.14 | 0.7391 |

| Taurodeoxycholate | 0.68 | 0.1915 | 1.63 | 0.7391 |

| 6-Beta-hydroxylithocholate | 0.65 | 0.151 | 1.31 | 0.6653 |

| Beta-muricholate | 0.59 | 0.0434 | 0.78 | 0.8506 |

| Alpha-muricholate | 0.59 | 0.0495 | 1.29 | 0.6653 |

| Tauroursodeoxycholate | 0.42 | 0.0126 | 0.84 | 0.9249 |

| Tauro(alpha + beta) muricholate | 0.43 | 0.0101 | 0.65 | 0.6653 |

Significance determined by two-way ANOVA, where sex and treatment were factors and corrected for multiple testing using the FDR. N = 8 per group.

Carbohydrate metabolism.

At 6 weeks of age, alterations in intermediates associated with glucose and fructose metabolism were seen in both male and female HFCS animals compared to controls (Table 7). Hepatic glucose and fructose levels were elevated in both male and female HFCS animals compared to controls, with compensatory decreases in intermediates of glucose and fructose metabolism such as phosphoenolpyruvate, glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-1-phosphate in HFCS males and females (Table 7). Likewise, levels of glycogen metabolites were significantly increased in male and female HFCS mice compared to controls; however, there was a sex effect with the magnitude of change being much higher in HFCS females compared to HFCS males (Table 7).

Table 7.

Fold change in carbohydrates in HFCS-exposed 6-week-old animals

| Female | q value | Male | q value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fructose | 1.46 | 8.36E-05 | 1.36 | 0.0021 |

| Glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) | 0.68 | 0.0037 | 0.74 | 0.0355 |

| Glucose | 1.09 | 0.0195 | 1.09 | 0.0355 |

| Fructose 1-phosphate | 0.46 | 0.0054 | 0.49 | 0.0044 |

| 2-Phosphoglycerate | 0.65 | 0.0016 | 0.76 | 0.0331 |

| 3-Phosphoglycerate | 0.7 | 0.0001 | 0.76 | 0.0025 |

| 1,3-Dihydroxyacetone | 1.2 | 0.0249 | 1.21 | 0.068 |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) | 0.57 | 0.0118 | 0.5 | 0.002 |

| Lactate | 0.68 | 0.1007 | 0.81 | 0.0331 |

| Maltose | 0.96 | 0.1332 | 1.03 | 0.2485 |

| Mannitol | 0.93 | 0.2239 | 2.39 | 0.0006 |

| Mannose | 1.04 | 0.1733 | 1.15 | 0.0243 |

| Sorbitol | 0.77 | 0.0114 | 0.95 | 0.2158 |

| Tagatose | 2.27 | 1.76E-07 | 1.44 | 0.0044 |

| Maltotriose | 1.13 | 0.0163 | 1.08 | 0.142 |

| Maltopentaose | 2.12 | 1.73E-05 | 1.4 | 0.028 |

| Maltohexaose | 3.44 | 1.33E-05 | 1.75 | 0.2485 |

Significance determined by two-way ANOVA, where sex and treatment were factors and corrected for multiple testing using the FDR. N = 8 per group.

At 30 weeks of age, glucose, glycogen and fructose pathways normalized to control values in both HFCS males and females with the exception of the isobar: fructose 1,6-diphosphate, glucose 1,6-diphosphate, which remained greater than 3-fold elevated in HFCS males (Supplementary Table 2 for review only).

Amino acids.

Multiple hepatic amino acids were significantly decreased in 6-week-old female HFCS mice (Supplementary Table 1 for review only). In contrast, levels of hepatic amino acids were either increased or not changed by HFCS consumption in male mice (Supplementary Table 1 for review only). Tryptophan metabolism plays an important role in hepatic lipid metabolism and morbidly obese individuals have been found to have low tryptophan levels (Brandacher et al. 2006). Similarly, HFCS female mice with increased fat mass had significantly reduced hepatic concentrations of tryptophan, its precursor anthranilate and its metabolite kynurenine at 6 weeks of age (Table 8). Hepatic levels of branched chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine and valine) were also significantly decreased in 6-week old female HFCS mice (Table 8). In contrast, there were no significant changes in these amino acids in male HFCS mice (Table 8). These changes more or less completely normalized at 30 weeks of age (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for review only).

Table 8.

Fold change in amino acids in HFCS-exposed 6-week-old animals

| Female | q value | Male | q value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kynurenine | 0.53 | 0.0002 | 1.07 | 0.3281 |

| Tryptophan | 0.9 | 0.0121 | 1 | 0.3504 |

| Anthranilate | 0.53 | 0.0078 | 0.86 | 0.2815 |

| C-glycosyltryptophan | 0.72 | 5.48E-05 | 0.86 | 0.0336 |

| Isoleucine | 0.81 | 0.0003 | 0.86 | 0.104 |

| Leucine | 0.83 | 0.0003 | 0.91 | 0.3141 |

| Valine | 0.74 | 4.25E-06 | 0.84 | 0.1483 |

Significance determined by two-way ANOVA, where sex and treatment were factors and corrected for multiple testing using the FDR. N = 8 per group.

Oxidative stress.

Despite higher triglyceride content in 6-week-old HFCS female mice compared to HFCS males, oxidative stress was more pronounced in males compared to females (Table 9). Levels of the cellular antioxidant peptide glutathione (in its reduced form) increased with administration of HFCS in both sexes, with a dramatically higher increase for females than males. In contrast, oxidized glutathione levels decreased in both HFCS groups, with males demonstrating a significant reduction. These changes indicate an increased capacity to maintain redox homeostasis in the female HFCS group. Several additional observations suggest that glutathione synthesis is increased in both sexes perhaps as a response to increased metabolic stress induced by HFCS ingestion. For example, methionine levels were reduced while homocysteine levels were increased with HFCS, indicating increased synthesis of cysteine, a component of glutathione. Also supporting an increase in cysteine biosynthesis were the significantly increased levels of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, which participates in the conversion of homocysteine to methionine, and 2-aminobutyrate, which is synthesized from a side-product of cysteine synthesis, in both males and females on HFCS. Other metabolic markers of oxidative stress include markedly elevated gamma-glutamylated amino acids (Supplementary Table 1 for review only) which are established markers of oxidative stress and reflect glutathione turnover. Lastly, ophthalmate, which is synthesized from 2-aminobutryate by the same enzymes involved in glutathione biosynthesis, was significantly elevated and the synthesis of taurine from cysteine appeared reduced as both hypotaurine and taurine levels were significantly decreased in HFCS animals. Ascorbate (vitamin C), another key antioxidant, was significantly elevated in HFCS animals. As further validation of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, we measured levels of hepatic TBARS in 6-week-old animals and found a marked increase in male but not female animals exposed to HFCS (fold change of control ± SD: 4.2±0.08 male, P = 2.87E-07; 1.1 ± 0.02 female, P = 0.7771; n = 8 each group, each sex). Overall, these changes in metabolite and TBARS in response to HFCS ingestion support a broad influence of HFCS on key pathways in redox homeostasis. By 30 weeks of age, there was no evidence of oxidative stress in liver of HFCS animals and all levels of the metabolites noted above returned to normal (Supplementary Table 2 for review only).

Table 9.

Fold change in oxidative stress metabolites in HFCS-exposed 6-week-old animals

| Female | q value | Male | q value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutathione (reduced) | 13.54 | 0.0004 | 1.57 | 0.154 |

| Glutathione (oxidized) | 0.91 | 0.091 | 0.62 | 6.02 E-05 |

| Methionine | 0.82 | 7.09 E-05 | 0.91 | 0.031 |

| Homocysteine | 1.39 | 0.12 | 1.67 | 0.018 |

| 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate | 4.10 | 2.47 E-07 | 1.85 | 0.005 |

| 2-Aminobutyrate | 2.86 | 1.74 E-09 | 3.69 | 2.10 E-10 |

| Ophthalmate | 5.32 | 5.35 E-07 | 5.82 | 1.42 E-06 |

| Hypotaurine | 0.48 | 2.79 E-05 | 0.38 | 3.30 E-06 |

| Taurine | 0.77 | 0.008 | 0.82 | 0.07 |

| Ascorbate | 1.84 | 2.95 E-05 | 1.29 | 0.03 |

Significance determined by two-way ANOVA, where sex and treatment were factors and corrected for multiple testing using the FDR. N = 8 per group.

HFCS induced gut microbiome changes

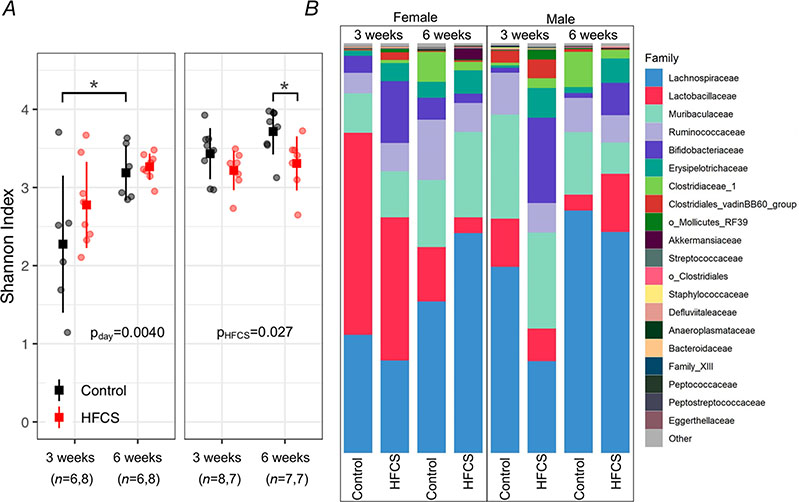

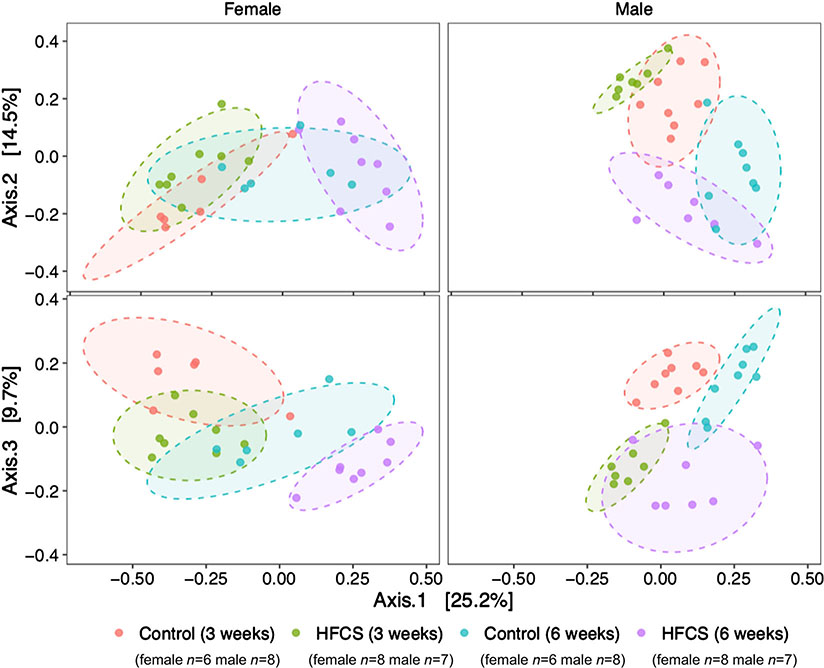

We collected faecal samples to assess the gut microbiota at the start and end of the study period (3 and 6 weeks of age). Read counts varied from 6919 to 49 914 with a median of 32 587. Alpha-diversity (Shannon index) was decreased with exposure to HFCS in males (main effect P = 0.027), particularly after 21 days of exposure (P = 0.028), but not in females (main effect P = 0.46; Fig. 9A and B). In females, alpha-diversity increased over time (P = 0.0040), particularly in controls (P = 0.0081), but this was not found in males (P = 0.084; Fig. 9A and B). Community composition visualized by PCoA using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity metric shows clustering by HFCS treatment and sample collection-day (Fig. 10). HFCS exposure significantly shifted the overall composition of the gut microbiota in both males (PERMANOVA; R2 = 0.15, P = 0.001) and females (R2 = 0.09, P = 0.001). Beta-dispersion did not differ by HFCS exposure. Overall community composition also shifted over time in both males (R2 = 0.23, P = 0.001) and females (R2 = 0.29, P = 0.001). Beta-dispersion also differed over time in both males (F = 9.9, P = 0.005) and females (F = 6.7, P = 0.02).

Figure 9. HFCS intake is associated with altered diversity and composition of gut microbiota.

A, in female offspring, alpha diversity (Shannon index) increased over time (main effect of day; P = 0.0040). Alpha diversity was decreased in HFCS males compared to control males (main effect of HFCS; P = 0.027). Individual data points are shown (circles) as well as mean (square) and standard deviation. Data were analysed by linear mixed model with treatment (HFCS vs. control) and day (3 weeks vs. 6 weeks) as fixed effects and mouse ID as a random effect. Pairwise comparisons were performed for significant main effects, with P < 0.05 indicated by asterisks. B, mean relative abundance of bacterial families in male and female control and HFCS mice after 3 weeks of HFCS exposure. N values are shown in the figure.

Figure 10. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) using the Bray Curtis dissimilarity metric shows distinct separation of gut microbial communities due to sex (PERMANOVA R2 = 6.9%, P = 0.005) and HFCS (PERMANOVA R2 = 16.0%, P = 0.001).

The effect of the interaction between HFCS and sex was also significant (PERMANOVA R2 = 11.1%, P = 0.001; n values are shown in the figure).

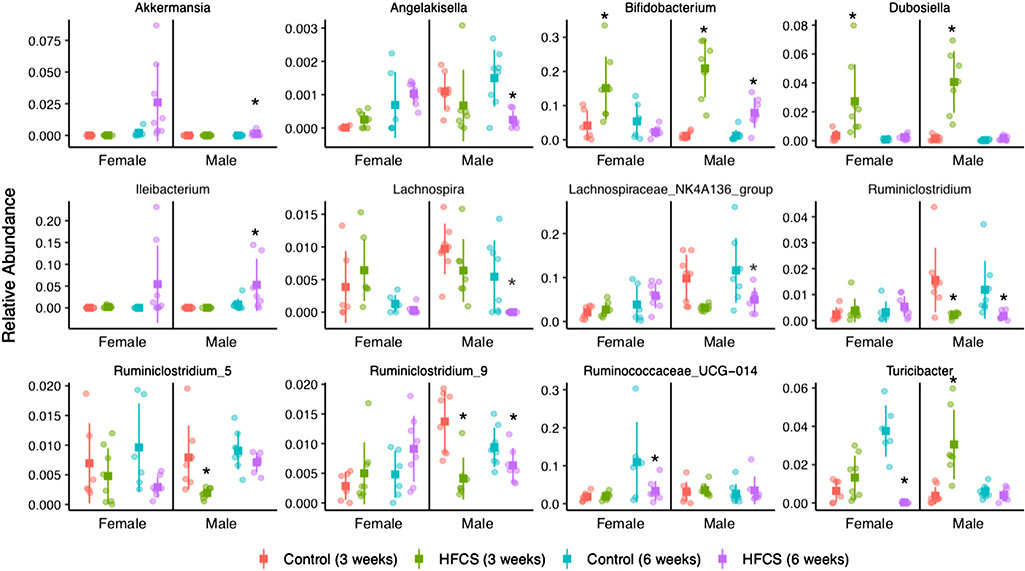

Interestingly, taxonomic summaries show significant shifts in the mean relative abundance of Bifidobacteriaceae and Erysipelotrichaeceae bacterial families at 3 weeks of age after only 1 day of HFCS exposure (Fig. 9B). Differential abundance analysis of genera-level count data confirmed these shifts (Fig. 11, Supplementary Table 3 for review only). Fewer genera were altered by HFCS in females than males after 1 day (5 and 11 genera, respectively) and 21 days of exposure (5 and 22 genera, respectively). HFCS increased Bifidobacterium and genera of the family Erysipelotrichaceae (including Dubosiella and Turicibacter) at 3 weeks of age after only 1 day of exposure in males and females, and these increases persisted in males at 6 weeks of age after 21 days of exposure. After 21 days of HFCS exposure (6 weeks of age), genera of the family Ruminococcaceae were decreased in males (including Angelakisella and Ruminiclostridium) and females (Ruminococcaceae_UCG-014), while genera of the family Lachnospiraceae were decreased only in males (including Lachnospira and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group). In males, HFCS increased the abundance of Akkermansia after 21 days of exposure, while in females Akkermansia increased over time in both HFCS-exposed and control mice.

Figure 11. Genera which differ significantly in abundance with HFCS exposure.

Relative abundance of genera at 3 and 6 weeks of age is shown for control and HFCS-exposed females and males. Significant effects of diet were assessed by DESeq2 for each time point and within each sex. *An adjusted P-value < 0.05 relative to sex and age-matched controls.

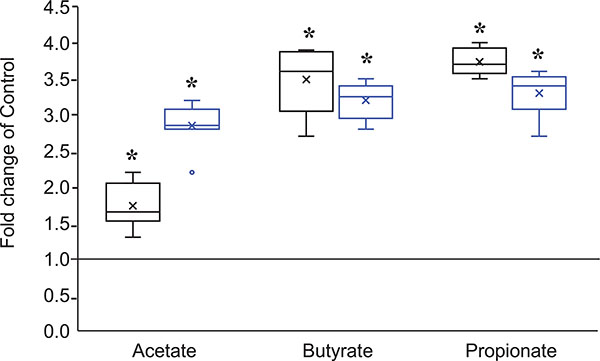

Microbial-associated metabolomics

Hepatic metabolomic analysis revealed altered levels of multiple metabolites that have been associated with an ‘obesogenic’ gut microbiome (Federici, 2019) in male and female HFCS animals at 6 weeks of age. Levels of butyrate, propionate and acetate were significantly elevated in HFCS males and females (Fig. 12). 2-Hydroxyisobutyrate, a gut microbial co-metabolite associated with obesity in humans (Calvani et al. 2010; Elliott et al. 2015), was also significantly increased in male HFCS animals (1.2-fold, q = 0.049). Trigonelline is a pyridine alkaloid that is involved in niacin metabolism by the liver and the gut microbiota (Sun et al. 2009; Calvani et al. 2010). Trigonelline levels were significantly reduced in HFCS compared to controls (0.86-fold, q = 0.043), similar to what has been observed in obese humans (Sun et al. 2009; Calvani et al. 2010). Levels of xanthine, a purine base, were also modestly reduced in HFCS animals (female: 0.91-fold, q = 0.003; male: 0.92, q = 0.013, consistent with the reduction in xanthine levels observed in obese humans (Sun et al. 2009; Calvani et al. 2010; Elliott et al. 2015). By 30 weeks of age, there were no differences between groups in these metabolites.

Figure 12. Box plots of microbiome metabolites altered in liver of HFCS male and female mice at 6 weeks of age.

Males represented by black boxes represent male and females represented by blue boxes. N = 8 mice per sex, per group. Data are expressed as fold change of control. Data were analysed by one-way ANOVA with Benjamini–Kieger–Yekutieli false discovery rate. *Statistically significant difference HFCS vs. control.

Discussion

Our study shows that after only 3 weeks of HFCS exposure during the peripubertal developmental period, significant sex-specific alterations in body composition, glucose tolerance, hepatic metabolism, oxidative stress and the gut microbiome can be seen. Furthermore, impaired glucose tolerance and fasting hyperinsulinaemia suggest that animals exposed to HFCS during adolescence develop insulin resistance, although this was not specifically measured. We have previously shown that in utero fructose exposure has sex-specific impacts, changes that can be seen as early as 10 days of postnatal life (Clayton et al. 2015). Similarly, the peri-pubertal developmental period is vulnerable to perturbations – and indeed pubertal timing itself is vulnerable to environmental influence (Connor et al. 2012; Chan et al. 2015). Although pubertal onset was not measured in this study it is likely that HFCS during the peripubertal period manifests as sex-specific outcomes (Widen et al. 2012).

Not surprisingly, the top metabolic pathway in the liver that was altered by sugar consumption was lipid metabolism (Tables 3 and 4). These deficits associated with adolescent sugar consumption are not secondary to increased overall kcal consumption or changes in chow intake, as the total kcal intake matched the control group and the pair feeding experiments show identical metabolic changes. Surprisingly, long after the HFCS exposure ceases, HFCS-exposed males had glucose intolerance at 30 weeks despite no significant change in fat mass, whereas HFCS-exposed females continued to have increased fat mass at 30 weeks, but have normal glucose homeostasis (Figs 3 and 4). Although the mechanisms responsible for these sex-specific metabolic observations need additional investigation, the data suggest that hepatic metabolic processes such as de novo lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, glycogenolysis and bile acid processing are all key pathways altered by HFCS in a sex-specific manner (Tables 3–7).

Fructose feeding, both acute and chronic, has been shown to stimulate hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL) in rats and in humans (Carmona & Freedland, 1989; Faeh et al. 2005; Kelley & Azhar, 2005; Lim et al. 2010; Basaranoglu et al. 2013; Crescenzo et al. 2013). DNL is accentuated more by excess dietary carbohydrate than by excess dietary fat (Schwarz et al. 1995). Our study shows that multiple pathways are involved in this process in response to short-term HFCS consumption during adolescence. Both males and females exposed to HFCS show decreases in intermediates of glycolysis (Table 7). Interestingly, decreases were also seen in intermediates of fructose metabolism, specifically fructose-1-phosphate and 3-phosphoglycerate (Table 7). These findings are similar to an in vitro study of isolated rat hepatocytes (Meissen et al. 2015) and suggest that there is increased consumption of glycolytic substrates due to HFCS ingestion into fatty acid biosynthesis. Our observation that hepatic expression of carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP), which increases conversion of carbohydrates into triglycerides, is markedly elevated in HFCS adolescent mice is consistent with this notion (Fig. 7). Furthermore, although upstream intermediates in fructose metabolism are decreased, downstream intermediates such as 1,3 dihydroxyacetone are increased in both males and females; this is significant because dihydroxyacetone can be converted to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, one of the substrates for de novo fatty acid synthesis (Table 4). Indeed, unsaturated and mono-unsaturated fatty acid moieties, particularly the SFAs palmitate, stearate and myristate, and mono-unsaturated fatty acids palmitoleate, eicosenoate and oleate were elevated in HFCS animals (Tables 3 and 4).

Additional mechanisms by which fructose stimulates hepatic lipid deposition include a reduction in hepatic fatty acid oxidation (Topping & Mayes, 1972) through the accumulation of the carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT-1) inhibitor malonyl-CoA (Roglans et al. 2002; Vilà et al. 2011). While we did not measure malonyl-CoA, our finding that HFCS ingestion markedly increases CoA levels (fatty acids are esterified to CoA before beta-oxidation in the mitochondria) and decreases expression of CPT-1 in females (but not males) suggests that hepatic fatty acid oxidation is depressed in HFCS adolescent females but not males. Furthermore, carnitine levels are significantly reduced in adolescent HFCS females, which also results in inhibition of free fatty acid oxidation. Finally, very long chain fatty acids which are principally metabolized by β-oxidation, are markedly elevated in HFCS females and modestly elevated in HFCS males. Together, these data demonstrate that impaired β-oxidation of fatty acids and enhanced de novo lipogenesis contribute to hepatic steatosis in HFCS animals. The sex difference in beta-oxidation of fatty acids combined with enhanced de novo lipogenesis are the likely mechanisms underlying increased triglyceride storage in livers of adolescent HFCS females compared to HFCS males.

Another product of fructose metabolism is liver glycogen which also may contribute to de novo fatty acid synthesis. Trioses [e.g. dihydroxyacetone (DHAP) and glycerols] were elevated in male and female HFCS animals. The subsequent metabolism of these trioses in the fructolytic pathway to pyruvate, which enters the Krebs cycle, is converted to citrate (which is increased at 6 weeks of age in HFCS animals) and subsequently directed toward de novo synthesis of the free fatty acid palmitate. The DHAP formed during fructolysis can also be converted to glycerol and then glycerol 3-phosphate for triglyceride (TG) synthesis. Thus, fructose can provide trioses for both the glycerol 3-phosphate backbone, as well as the free fatty acids in triglyceride synthesis. Incidentally, the short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) acetate and buytyrate may also directly increase fatty acid oxidation and glycogen storage (Canfora et al. 2015). Whether our observed increase in hepatic SCFA was the result of increase microbial production of these substrates is difficult to say, and future studies need to include caecal measures of SCFAs.

While hepatic fatty acid and triglyceride levels were elevated in female compared to male HFCS adolescent animals, females were protected from the deleterious effects of HFCS-induced oxidative stress. A number of mechanisms contribute to the ability of females to mount a more vigorous antioxidant defence. Levels of the cellular antioxidant peptide glutathione (in its reduced form) increased with administration of HFCS in both sexes, with a dramatically higher increase for females than males. Ascorbate (vitamin C) is another key antioxidant which can be synthesized in mice (but not humans) from glulono-1,4-lactone. In this study, ascorbate was significantly elevated in females and males, but again, levels in females were higher, and both precursor and metabolite, threonate, were significantly decreased in HFCS males. Arachidonate levels were reduced in HFCS females compared to HFCS males and this metabolite is the precursor to leukotrienes, which have been shown to activate NFκB, and enhance the release of inflammatory adipokines MCP-1 and IL-6 from adipose, directly contributing to insulin resistance (Horrillo et al. 2010; Martinez-Clemente et al. 2011). Palmitoleate, a monounsaturated fatty acid, is a bioactive lipid that contributes to hepatic steatosis but suppresses liver inflammatory responses in mice (Guo et al. 2012). Levels of this fatty acid are markedly elevated in HFCS females compared to males. Together, these changes suggest HFCS-exposed females exhibit marked antioxidant synthesis in excess of oxidative demands and an increased capacity to maintain redox homeostasis. Furthermore, levels of glutathione (reduced form) and ascorbate were higher in control females compared to males, suggesting that females have an innate ability to mount a more robust antioxidant defence compared to males.

Another intriguing finding was the marked sex-specific decrease in bile acids in female HFCS mice at 6 weeks which were also identified at 30 weeks of age (Tables 5 and 6). Bile acids are potent regulators of hepatic triglyceride metabolism, affect insulin sensitivity and glucose disposal, and are critical for normal absorption of lipids from the gastrointestinal tract. Low levels may contribute to the increase in fat mass observed at both 6 and 30 weeks of age in HFCS females. HFCS primarily altered levels of unconjugated bile acids in 6-week-old females and, for the most part, conjugated bile acids were unaffected with the exception of the taurine conjugate tauroursodeoxycholate, TUDCA. Levels of this bile acid were significantly higher in HFCS females compared to controls. TUDCA is effective in protection of hepatocytes and restoration of glucose homeostasis by reduction of oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress (Vang et al. 2014). Altered levels in HFCS females may play a role in the partial protection against the oxidative stress that was observed in HFCS males. At 30 weeks of age, both unconjugated and tauro-conjugated bile acids were significantly reduced in HFCS females.

Bile acid synthesis is mainly controlled by negative feedback regulation of cyp7a1. Expression of cyp7a1 is down-regulated in HFCS females which is associated with a marked reduction in the two primary bile acids, cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid in 6- and 30-week-old female mice (Fig. 8). Surprisingly, mRNA levels of FXR were not altered by HFCS exposure. FXR is expressed at high levels in the liver and intestine (Kliewer et al. 2015). Chenodeoxycholic acid and other bile acids are natural ligands for FXR (Kliewer et al. 2015). One of the primary functions of FXR activation is the suppression of Cyp7a1 (Kliewer et al. 2015). Thus, the reduction in expression of Cyp7a1 is probably due to an alternate mechanism.

Exposure to HFCS leads to increased hepatic content of many long-chain PUFAs with greater concentrations measured in females than in males (Tables 3 and 4). In addition to increased hepatic PUFA concentrations in female livers at 6 weeks of age, there was also increased hepatic triglyceride content (Fig. 5). Fatty acids are converted to triglycerides in the liver followed by export into the circulation by VLDL. However, when hepatic fatty acid concentrations are profoundly increased, the triglyceride export pathway via VLDL transport exceeds capacity, which results in a persistent increase in fatty acid concentrations within the liver. These fatty acid species ultimately undergo beta-oxidation resulting in increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which can ultimately contribute to the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). One such ROS that was robustly increased over 5-fold in males and female was ophthalmate (q < 0.05) (Table 9). Previous studies examining the effects of prolonged exposure to HFCS on hepatic metabolism in adult rodents report that HFCS exposure is associated with a reduction the capacity of the liver to metabolize ROS due to reduced glutathione metabolites and reduced concentrations of superoxide dismutase in the setting of increased hepatic lipid beta-oxidation (Lebda et al. 2017). Increased ROS contribute to both the onset and the continuation of insulin resistance (Houstis et al. 2006) and hepatocyte apoptosis, which may further contribute to the development of NAFLD. In contrast, we found that female juvenile rats at 6 weeks of age that were exposed to HFCS were able to mount a robust glutathione antioxidant response, which may explain in part why juvenile female rats do not have evidence of insulin resistance (Tables 1 and 9). In males there was a failure to upregulate the glutathione response resulting in elevated levels of ROS leading to hepatic insulin resistance. In all, these findings suggest that increased concentrations of long-chain PUFAs lead to increased oxidation of lipid species and the generation of ROS while at the same time lead to a reduction in the antioxidant capacity of the liver and the development of hepatic insulin resistance.

While the most profound changes in the metabolome occurred in the fatty acid pathways, multiple other metabolic processes were affected by HFCS ingestion. Amino acid metabolism was moderately disrupted in both 6-week-old female and male HFCS animals (Table 8). Gamma glutamyl amino acids, which are responsible for maintaining appropriate supplies of the antioxidant glutathione, were mildly increased in male liver. Despite reports of increased branched chain amino acids in adults with NAFLD (Kalhan et al. 2011), we found mild decreases in branched chain amino acids in the juvenile rat livers exposed to HFCS and this is consistent with a study in adolescents (mean age 13 years) with NAFLD that found no increases in branched chain amino acid levels (Goffredo et al. 2017). In addition, we found statistically significant decreases in the tryptophan pathway, including its precursor anthranilate and metabolite kynurenine in livers of 6-week female rat exposed to HFCS. Since tryptophan metabolism results in the production of NAD+, these results suggest that exposure to HFCS in female juvenile rats leads to an impairment of NAD+ production, which is an important co-factor in hepatic metabolic reactions. In addition to functioning as an important co-factor in the generation of ATP, NAD+ is a substrate for the sirtuin signalling pathway and is important for mitochondrial biogenesis and function and for insulin sensitivity (Elhassam et al. 2017).

We show that as little as 1 day of exposure to HFCS, at 3 weeks of age, significantly altered the gut microbial profile of male (nine genera were different) and female (nine genera were different) mice (Fig. 9). This effect remained in females after 21 days of exposure (age 6 weeks), maintaining a modest five genera significantly different compared to controls (Fig. 9). Interestingly, in males we observe an amplified impact: after 21 days of exposure, 18 genera were significantly different. This magnification of the impact of HFCS on microbial populations suggests that males may be more vulnerable to HFCS, consistent with many of our other outcome measures. After 21 days of HFCS exposure we show that alpha diversity is significantly lower in HFCS males compared to control males – an effect that was absent in females.

HFCS results in a significant increase in the abundance of Bifidobacterium in both males (at both 3 and 6 weeks) and females (only 3 weeks) (Fig. 11). Although Bifidobacteria are typically associated with intestinal health (Leahy et al. 2005), they may also contribute to hepatic lipogenesis (Zhao et al. 2020) by metabolising fructose to acetate (Falony et al. 2006), which we found to be increased in both male and female livers at 6 weeks (Fig. 12). HFCS males show a significant loss of multiple members of the family Ruminococcaceae (and in females but only Ruminococcaceae UCG-014). This genus is associated with the production of butyrate from the fermentation of indigestible polysaccharides and is associated with intestinal epithelial integrity (Farhadi et al. 2008; Thuy et al. 2008; Harrison et al. 2018). Consistent with a loss of bacteria that produce SCFAs, Clostridiaceae and Lachnospiracae family abundances were also decreased overall (only one genus of Clostridiaceae was decreased in males; Clostridium_sensu stricto_1). Whether these shifts in key SCFA-producing bacteria contribute to the changes that we observed in hepatic lipogenesis and glucose metabolism is unknown but has been previously suggested (Bischoff & Bergheim, 2008). Of note, Akkermansia municiphila species abundance was increased in HFCS-exposed males, which has been observed in at least one other report of fructose intake (Lambertz et al. 2017), despite the fact that this bacterium is associated with intestinal health (Everard et al. 2013; Reunanen et al. 2015; Depommier et al. 2019). Its rise in the context of HFCS exposure may reflect HFCS-induced changes at the level of intestinal epithelial mucosa (since it is a mucin degrader) (Derrien et al. 2004), but these experiments were beyond the scope of this study.

In females we show more modest shifts in the intestinal microbiota. HFCS was associated with a (30-fold) (Fig. 11) increase in the abundance of the gram-positive bacterium Ileibacterium and although the function of this bacteria is currently unknown, its abundance has previously been shown be 10-fold higher on a high-fat, high-sucrose diet compared to controls (Cox et al. 2017). HFCS females showed a modest (2.3-fold) decrease in SCFA-producing Ruminococcaceae UCG-014, but whether this contributes to changes in luminal contents of SCFAs is unknown. Together, our microbial profiling data suggest that sex-specific effects of HFCS exist and that males are much more vulnerable to diet-induced shifts that persist over time, compared to females.

Decreased levels of trigonelline (N-methylnicotinate) indicate a class-specific metabolism of niacin, which is an essential vitamin involved in major physiological functions such as a coenzyme in tissue respiration, and carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Niacin requirements are satisfied by both dietary sources and biosynthesis through a tryptophan-mediated metabolism ensured by the liver and the gut microbiota. Decreased trigonelline has been related to a depletion of S-adenosylmethionine, as it is consumed in the trans-sulfuration pathway in order to regenerate glutathione stores that are depleted by obesity-related metabolic stress (Sun et al. 2009).

While the HFCS feeding protocol used in our study is similar to that described in other reports of rodent models (REFS), there are caveats and limitations in applying the metabolic information gained from our studies to better understand the effects of excessive HFCS intake in human adolescents. One of the largest differences between our animal model and humans is that the caloric contribution of HFCS to total energy intake is greater for the mouse compared to the human. Furthermore, the form of administration of HFCS in water may modify the rate of absorption of monosaccharides, thereby increasing the glycaemic effect. However, consumption of energy drinks by adolescents which contain large amounts of HFCS are likely to have similar effects.

In summary, a short-term exposure to HFCS during the adolescent developmental window induced fatty liver, altered multiple critically important metabolic pathways, many of which were also altered in adulthood, and changed the microbiome. The sex differences in both normal and HFCS animals are intriguing and need further exploration.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

The prevalence of obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children is dramatically increasing at the same time as consumption of foods with a high sugar content. Intake of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is a possible aetiology as it is thought to be more lipogenic than glucose.

In a mouse model, HFCS intake during adolescence increased fat mass and hepatic lipid levels in male and female mice. However, only males showed impaired glucose tolerance.

Multiple metabolites including lipids, bile acids, carbohydrates and amino acids were altered in liver in a sex-specific manner at 6 weeks of age. Some of these changes were also present in adulthood even though HFCS exposure ended at 6 weeks.

HFCS significantly altered the gut microbiome, which was associated with changes in key microbial metabolites.

These results suggest that HFCS intake during adolescence has profound metabolic changes that are linked to changes in the microbiome and these changes are sex-specific.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant no. DK062965 (R.A.S.); Scholarship from the Farncombe Family Digestive Health Research Institute, Canada (K.K.); Canada Research Chairs Program, and Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant no. MWG 146333 (D.S.) and by core services provided by the DERC at the University of Pennsylvania from a grant sponsored by NIH DK19525.

Biography