Abstract

Purpose:

Active surveillance has gained acceptance as an alternative to definitive therapy in many men with prostate cancer. Confirmatory biopsies to assess the appropriateness of active surveillance are routinely performed and negative biopsies are regarded as a favorable prognostic indicator. We sought to determine the prognostic implications of negative multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-transrectal ultrasound guided fusion biopsy consisting of extended sextant, systematic biopsy plus multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging guided targeted biopsy of suspicious lesions on magnetic resonance imaging.

Materials and Methods:

All patients referred with Gleason Grade Group 1 or 2 prostate cancer based on systematic biopsy performed elsewhere underwent confirmatory fusion biopsy. Patients who continued on active surveillance after a positive or a negative fusion biopsy were followed. The baseline characteristics of the biopsy negative and positive cases were compared. Cox regression analysis was used to determine the prognostic significance of a negative fusion biopsy. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to estimate Grade Group progression with time.

Results:

Of the 542 patients referred with Grade Group 1 (466) or Grade Group 2 (76) cancer 111 (20.5%) had a negative fusion biopsy. A total of 60 vs 122 patients with a negative vs a positive fusion biopsy were followed on active surveillance with a median time to Grade Group progression of 74.3 and 44.6 months, respectively (p <0.01). Negative fusion biopsy was associated with a reduced risk of Grade Group progression (HR 0.41, 95% CI 0.22–0.77, p <0.01).

Conclusions:

A negative confirmatory fusion biopsy confers a favorable prognosis for Grade Group progression. These results can be used when counseling patients about the risk of progression and for planning future followup and biopsies in patients on active surveillance.

Keywords: prostatic neoplasms, diagnostic imaging, image-guided biopsy, watchful waiting, prognosis

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed noncutaneous malignancy in American men with more than 160,000 new cases in 2018.1 However, only approximately 30,000 men will die of the disease. Furthermore, low grade cancers have an especially good prognosis.1,2

AS has increasingly served as a primary management strategy for NCCN® (National Comprehensive Cancer Network®) very low risk and many low risk PCa cases due to the often indolent nature of the disease.3,4 However, since GG progression can occur, periodic surveillance biopsies are recommended.5 For instance, many protocols require a confirmatory biopsy within 1 year of entry into AS.5 After this confirmatory biopsy the frequency of additional biopsies is highly variable, ranging from 1 to 4 years.6,7

No matter how stringent the AS protocol, a negative biopsy is regarded as a reassuring factor. A negative biopsy implies that the volume of a tumor is likely small and, thus, it tends to evade detection by needle biopsy. The rate of negative biopsies while on AS varies from 21% to 52% with standard SB but equivalent FB rates have not been reported.5, 8–10 For example, Ganesan et al examined men with GG 1 (Gleason score 3 + 3) and GG 2 (Gleason score 3 + 4) on AS and reported an almost 50% rate of negative confirmatory biopsies at 1 year, which conferred a 50% reduction in the progression rate.8

With advances in mpMRI urologists can rely on imaging to detect lesions which then become targets for mpMRI-TRUS guided FB.11 The main benefit of FB is the ability to detect more clinically significant PCa compared to SB alone.12 Without this information many patients with clinically significant disease may be inappropriately placed on AS. Prior studies of the rate of GG reclassification after FB have shown that almost 30% of cases are upgraded, making them potentially ineligible for AS.13,14

We examined patients referred to our institution with a diagnosis of GG 1 or 2 PCa who were undecided on PCa treatment and underwent FB to confirm eligibility for AS. We sought to determine the implication of a negative FB, consisting of all targeted lesions and SB, for disease progression and the rate of AS discontinuation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

We queried a prospectively maintained database for all patients referred to the NIH (National Institutes of Health) from 2007 through 2017 with a diagnosis of GG 1 or 2 PCa based on 12-core extended sextant SB performed elsewhere. These patients underwent mpMRI and confirmatory FB, consisting of mpMRI-TRUS guided targeted biopsy of suspicious lesions, and SB to determine AS eligibility. Patients who elected definitive therapy or decided not to pursue AS at our institution were then excluded from analysis.

There were no strict criteria based on PSA, PSA density or tumor volume estimated by MRI or biopsy results. Patients with any history of focal treatment, radiation therapy or androgen deprivation therapy were excluded from study. Only patients on AS with at least 2 biopsies were included in study so that a GG change could be documented. Patients with a negative FB and those with a positive FB who were still eligible for AS (GG 1 or 2) were followed with a yearly PSA test, clinical examination and mpMRI. Repeat FB was encouraged at 1 to 2-year intervals if deemed clinically warranted based on changes in mpMRI, PSA or examination.

Baseline demographic and imaging data were obtained, including patient age, race, PSA, MRI calculated prostate volume, a validated in-house MRI scoring system, and lesion number and size. Biopsies were reviewed to determine whether patients had GG progression, defined as GG upgrading, independent of tumor volume. In patients who discontinued AS and elected RP the final pathology results were recorded to determine any adverse pathological features.

Imaging and Biopsy Protocol

Each patient underwent 3 Tesla mpMRI using an Achieva device (Phillips Healthcare, Cambridge, Massachusetts) with a BPX-30 endorectal coil (Medrad, Warrendale, Pennsylvania) and a 16-channel SENSE cardiac surface coil (Phillips Healthcare) as described previously.15 mpMRI sequences consisted of triplanar T2-weighted, diffusion-weighted imaging with b-values of 2,000 seconds per mm2, apparent diffusion coefficient mapping and dynamic contrast enhancement.

Two radiologists experienced with mpMRI identified prostatic lesions assigned PCa suspicion levels based on a previously validated in-house MRI SS. This 5-point tiered system grades each mpMRI as at low, low-moderate, moderate, moderate-high or high suspicion for PCa. The in-house SS correlates with the PI-RADS version 2. The exception is a PI-RADS 4 lesion, which may have a lower cancer detection rate than a lesion with a moderate-high likelihood of PCa due to the incorporation of extraprostatic extension features.16 The PI-RADS was not in use at the beginning of the study and, therefore, it was not used in this analysis.

At the time of study entry and at each subsequent FB all patients underwent 12-core extended sextant SB and targeted biopsy of all lesions seen on repeat mpMRI. Each lesion identified by mpMRI was sampled with at least 2 or more cores based on physician discretion. All biopsies were performed by 1 of 2 physicians with extensive experience using the UroNav fusion biopsy platform (Invivo, Gainesville, Florida).17

Analysis

Univariate analysis was performed to compare the positive and negative FB groups at presentation using the Student t-test and the chi-square test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Kaplan-Meier survival curves representing those remaining on AS were constructed to determine median time to AS discontinuation. Similarly Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to determine GG PFS. Cox proportions hazard regression analysis was then performed on all baseline clinical and MRI data on the entire cohort and then individually analyzed in the positive and negative FB groups. Statistical analyses were completed with STATA®, version 15.0 with p <0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 542 potential AS candidates were referred to our institution with a diagnosis of GG 1 PCa in 466 and GG 2 PCa in 76. These men then underwent mpMRI guided FB (fig. 1). Of these patients 110 of 466 (21.5%) in the GG 1 group and 10 of 76 (13.2%) in the GG 2 group had a negative FB and elected to continue AS. Overall 224 of these 542 cases (41.3%) were upgraded to a higher GG, including 205 of the 466 (44.0%) in the GG 1 group and 19 of the 76 (25.0%) in the GG 2 group which were upgraded after mpMRI guided FB (table 1). After initial confirmatory FB 210 patients sought definitive treatment. The remaining 332 men continued on AS after a negative or a positive confirmatory FB.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients included in study

Table 1.

Fusion biopsy results and outcomes of patients with 12-core systematic biopsy done elsewhere who were referred for treatment

| No. Grade Group (%) |

||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| No. pts | 466 | 76 |

| Confirmatory fusion biopsy: | ||

| No Ca detected | 110 (23.6) | 10 (13.2) |

| GG 1 | 151 (32.4) | 10 (13.2) |

| GG 2 | 139 (29.8) | 37 (48.7) |

| GG 3 or greater | 66 (14.2) | 19 (25.0) |

| Decided on active surveillance: | ||

| No upgrade | 246 (97.2) | 35 (61.4) |

| Upgrade | 50 (24.5) | 0 |

Of the 332 patients who elected to continue AS 182 underwent a subsequent FB and were included in study. Of these men 122 and 60 had a positive and a negative FB, respectively. In the positive and negative FB groups the mean ± SD time from SB done elsewhere to referral plus FB was 16.4 ± 16.6 and 12.2 ± 12.4 months, respectively (p = 0.08). Median followup in the entire cohort was 43.6 months (range 6.7 to 121.9). Patients in the positive and negative FB groups underwent an average of 2.53 ± 0.81 and 2.73 ± 0.75 biopsy sessions, respectively (p = 0.11). Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of these 2 groups. The positive FB group had more cases of highly suspicious lesions based on our in-house MRI scoring system (8.2% vs 0%, p = 0.02).

Table 2.

Baseline demographics of positive and negative fusion biopsy groups placed on active surveillance

| Fusion Biopsy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pos | Neg | p Value | |

| No. pts | 122 | 60 | – |

| Mean ± SD age | 62.6 ± 7.1 | 60.9 ± 6.6 | 0.12 |

| Mean ± SD PSA (ng/ml) | 5.6 ± 3.1 | 5.4 ± 3.9 | 0.71 |

| Mean ± SD MRI prostate vol (ml) | 52.1 ± 22.3 | 53.6 ± 29.8 | 0.70 |

| Mean ± SD PSA density (ng/ml/ml) | 0.12 ± 0.07 | 0.11 ± 0.09 | 0.41 |

| No. African American (%) | 10 (8.2) | 8 (12.9) | 0.31 |

| Mean ± SD mos from pos biopsy elsewhere | 16.4 ± 16.6 | 12.2 ± 12.4 | 0.08 |

| Mean ± SD % biopsy elsewhere total pos cores | 9.5 ± 13.0 | 9.4 ± 9.0 | 0.96 |

| No. GG 2 biopsy elsewhere (%) | 12 (9.8) | 9 (14.5) | 0.36 |

| No. anterior tumor (%) | 42 (34.4) | 19 (30.6) | 0.61 |

| Mean ± SD No. lesions | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 0.05 |

| No. no MRI targets (%) | 4 (3.3) | 1 (1.7) | 0.53 |

| Mean ± SD largest lesion size (cm) | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.00 |

| No. in-house MRI suspicion score greater than moderate (%) | 10 (8.2) | 0 | 0.02* |

| Mean ± SD No. biopsy sessions | 2.53 ± 0.81 | 2.73 ± 0.75 | 0.11 |

Statistically significant (p <0.05).

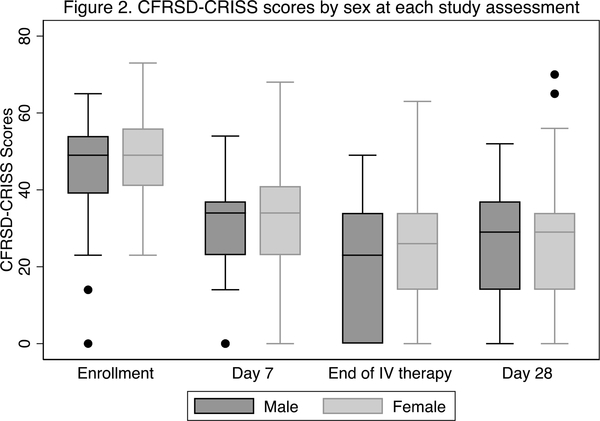

A total of 51 (41.8%) and 17 cases (27.4%) of positive and negative FBs progressed on subsequent FB (p = 0.06). Median PFS was longer in the negative FB group than in the positive FB group (74.3 vs 44.6 months, p <0.01, fig. 2). Of the entire cohort 76 men (62.3%) in the positive FB group and 55 (91.7%) in the negative FB group continued on AS (p <0.01). The positive FB group had a median AS continuance time of 64.4 months while the negative FB group continued on AS for a median of 89.7 months (p <0.01, fig. 2). In the negative FB group 23 patients (38.3%) had no PCa on subsequent FB at a median followup of 38.8 months (range 14.5 to 83.3). The remaining 37 men (61.7%) had a subsequent positive FB at a median of 27.3 months (range 12.4 to 63.5).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of positive and negative FB groups remaining on AS (A) and with GG PFS (B). Median PFS was 44.6 and 74.3 months in positive and negative FB groups, respectively (p <0.01). Time in patients continuing on AS was 64.4 and 89.7 months in positive and negative FB groups, respectively (p <0.01).

At the time of biopsy in the negative FB group with progression 12 men had GG 2, 1 had GG 3 and 2 had GG 4 disease. All 5 men with a negative FB who discontinued AS elected RP after GG progression. Final pathology after RP revealed that all 5 cases were stage pT2cN0 or less, 3 were GG 2 and 2 were GG 4.

Cox regression analysis was then performed in the entire cohort (table 3). Factors significant for GG progression were patient age (HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.01–1.09, p = 0.03), PSA density (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.07, p <0.01) and confirmatory FB status (negative FB HR 0.41, 95% CI 0.22–0.77, p <0.01). When Cox regression analysis was performed in the positive FB group, age (HR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01–1.10, p = 0.02) and PSA density (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.07, p <0.01) retained significance. Additionally, the largest lesion diameter on mpMRI was significant (HR 2.04, 95% CI 1.12–3.72, p = 0.02). After Cox regression analysis of the negative FB group none of these baseline factors were significant for progression.

Table 3.

Cox proportions hazard regression of entire cohort, GG 1 group and GG 2 group predicting GG progression on subsequent biopsy

| Entire Cohort |

Pos Fusion Biopsy |

Neg Fusion Biopsy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age/yr | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) | 0.03* | 1.06 (1.01–1.10) | 0.02* | 1.04 (0.94–1.16) | 0.43 |

| PSA density | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | <0.01* | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | <0.01* | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | 0.39 |

| African American | 1.31 (0.54–3.18) | 0.55 | 2.60 (0.93–7.26) | 0.07 | 0.56 (0.07–4.59) | 0.59 |

| In-house MRI suspicion score greater than moderate | 0.40 (0.10–1.70) | 0.22 | 0.42 (0.10–1.78) | 0.24 | – | – |

| No. MRI visible lesions | 1.05 (0.83–1.34) | 0.67 | 0.97 (0.74–1.26) | 0.81 | 1.54 (0.77–3.06) | 0.22 |

| Largest lesion diameter | 1.29 (0.73–2.28) | 0.38 | 2.04 (1.12–3.72) | 0.02* | 0.27 (0.05–1.45) | 0.13 |

| Neg fusion biopsy | 0.41 (0.22–0.77) | <0.01* | – | – | – | – |

Statistically significant (p <0.05).

DISCUSSION

These results demonstrate that a negative FB in the setting of AS confers a favorable prognosis for remaining on AS. Our study showed an almost 60% decreased chance of progression in patients after a negative FB. This finding is like that in prior studies of the prognostic impact of negative SBs in AS cohorts in the era before mpMRI.5,8,9,18 For instance, Wong et al found that patients with a negative SB at 1 year were 53% less likely to show progression than those with a positive biopsy at 1 year and the PFS rate at 5 years was 85.2%.9 Patients in the PASS (Canary Prostate Active Surveillance Study) were 50% less likely to show progression following the first negative SB and 85% less likely after the second negative SB.18

Notably these studies included only patients with GG 1 PCa5,8,9,18 while our study also included men with GG 2 disease. Also, we applied no PSA or PSA density threshold. Therefore, our findings may be applicable to more men who do not fit more stringent AS criteria. Without the strict use of AS criteria higher grade or clinically significant disease can be ruled out in patients by mpMRI with its high negative predictive value.19

Our overall rate of negative confirmatory biopsies was 22%, similar to previous studies of the rate of AS reclassification after MRI and FB.5,8–10 Our rate of upgrading cases in which PCa was diagnosed only by SB was 44% on confirmatory FB. This finding has implications not only for AS but also for all PCa treatment modalities. However, this rate of upgrading at FB is higher than in prior retrospective and prospective trials comparing SB to mpMRI with targeted biopsy, in which the incidence ranges from 12% to 30%.12,20 This higher than expected rate may have been due to our patient study population, which included only men with a diagnosis of PCa, in contrast to the biopsy naïve men with inherently lower PCa rates in the mentioned studies.

Tumor size predicted progression in positive FB cases on Cox regression analysis of the entire cohort. Tumor volume has been shown to correlate with more aggressive disease.21 With the advances in mpMRI urologists can now reliably estimate tumor volume compared with using systematic biopsy alone, which provided only a surrogate of tumor volume.11,22

One main difference between the positive FB and negative FB groups was the higher incidence of a high MRI SS in the positive FB group. We primarily used the in-house MRI scoring system instead of the PI-RADS since the latter was available only in the last 2 years of this 10-year study. We acknowledge that this in-house MRI scoring system is not universally adopted. However, it has correlated with an increased likelihood of clinically significant PCa and it generally agrees with PI-RADS version 2.23 Mehralivand et al prospectively validated PI-RADS and the highest likelihood lesions (PI-RADS 5) had almost 90% specificity for diagnosing PCa.24 In our study almost all patients followed on AS had targetable lesions which were seen on mpMRI. However, a few cases were graded as at high suspicion for PCa based on the in-house SS. These low to moderate likelihood SS lesions (less than PI-RADS 5) have an overall cancer detection rate of 20.1% to 39.1%.24 Our cancer detection rate in this study was higher likely due to the inclusion of only men with a known diagnosis of PCa.

Reports have described the use of mpMRI to monitor patients on AS for progression and sometimes the only indication of progression on imaging was lesion size.25,26 Frye et al found that stable mpMRI had 81% negative predictive value to detect pathological progression.25 However, a proportion of men have GG progression despite stable MRIs.27 Therefore, the decision to perform followup biopsy should be based on the individual risk factors for progression of each patient as well as time since the last biopsy. As mpMRI is more commonly integrated into AS protocols, standardized reporting of MRI lesions and FB cores will help urologists follow these patients and aid in future AS research.26

Furthermore, mpMRI enables physicians to better detect not only the true grade of PCa but also the true volume of disease and any potential adverse pathological features better than relying solely on PSA and SB.28 When mpMRI scans are combined with FB, urologists can more confidently select patients who will be benefit from AS.14

Lastly, median PFS was more than 6 years in patients with a negative FB. The progression rate was 5% (3 of 60 patients) and 10% (6 of 60) at 2 and 3 years, respectively. Urologists should consider the entirety of the patient, the disease and the risks associated with the procedure when deciding when to rebiopsy. Patients with a negative FB should be considered for a longer duration until followup biopsy at a minimum interval of 2 to 3 years. However, an important caveat to this is the possibility of a false-negative targeted biopsy. When PCa is still suspected after a negative FB due to worrisome mpMRI findings, all possibilities of error should be investigated, including PCa mimics, imaging acquisition errors and fusion biopsy misregistration.29

CONCLUSIONS

A negative FB while on AS was associated with a nearly 60% reduction in the risk of GG progression and a median time to progression of more than 6 years. These patients are more likely to have low volume disease and often a low suspicion score on MRI. With its negative predictive value for ruling out high grade disease mpMRI along with a negative biopsy confirming these findings should be reassuring to patients treated with AS. A negative FB on AS, which is a powerful predictor of favorable outcomes on AS, can be used to counsel patients regarding the risk of progression. This information can help urologists decide how often to plan followup visits as these patients may be offered longer intervals between subsequent followup examinations, imaging and biopsies.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author certifies that, when applicable, a statement(s) has been included in the manuscript documenting institutional review board, ethics committee or ethical review board study approval; principles of Helsinki Declaration were followed in lieu of formal ethics committee approval; institutional animal care and use committee approval; all human subjects provided written informed consent with guarantees of confidentiality; IRB approved protocol number; animal approved project number.

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH (National Institutes of Health), NCI (National Cancer Institute), Center for Cancer Research and Center for Interventional Oncology, and a research grant from the Dr. Mildred Scheel Foundation, Bonn, Germany (SM).

The NIH and Philips have a cooperative research and development agreement, and share intellectual property in the field; the NIH and authors receive licensing royalties for related intellectual property and associated technologies, and the NIH owns intellectual property in the field.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AS

active surveillance

- FB

fusion biopsy

- GG

Gleason Grade Group

- mpMRI

multiparametric MRI

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PCa

prostate cancer

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PI-RADS™

Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- RP

radical prostatectomy

- SB

12-core systematic biopsy

- SS

scoring system

- TRUS

transrectal ultrasound

Footnotes

Financial interest and/or other relationship with Philips Invivo.

No direct or indirect commercial, personal, academic, political, religious or ethical incentive is associated with publishing this article.

Contributor Information

Jonathan B. Bloom, Urologic Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

Graham R. Hale, Urologic Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

Samuel A. Gold, Urologic Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

Kareem N. Rayn, Urologic Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

Clayton Smith, Molecular Imaging Program, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Sherif Mehralivand, Urologic Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; Molecular Imaging Program, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; Department of Urology and Pediatric Urology, University Medical Center Mainz, Mainz, Germany.

Marcin Czarniecki, Molecular Imaging Program, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Vladimir Valera, Urologic Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Bradford J. Wood, Center for Interventional Oncology, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Maria J. Merino, Laboratory of Pathology, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

Peter L. Choyke, Molecular Imaging Program, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Howard L. Parnes, Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

Baris Turkbey, Molecular Imaging Program, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Peter A. Pinto, Urologic Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; Center for Interventional Oncology, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68: 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eggener SE, Scardino PT, Walsh PC et al. : Predicting 15-year prostate cancer specific mortality after radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2011; 185: 869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albertsen PC, Hanley JA and Fine J: 20-Year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 2005; 293: 2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooperberg MR and Carroll PR: Trends in management for patients with localized prostate cancer, 1990–2013. JAMA 2015; 314: 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dall'Era MA, Albertsen PC, Bangma C et al. : Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol 2012; 62: 976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter HB, Kettermann A, Warlick C et al. : Expectant management of prostate cancer with curative intent: an update of the Johns Hopkins experience. J Urol 2007; 178: 2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Bergh RC, Vasarainen H, van der Poel HG et al. : Short-term outcomes of the prospective multicentre 'Prostate Cancer Research International: Active Surveillance' study. BJU Int 2010; 105: 956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganesan V, Dai C, Nyame YA et al. : Prognostic significance of a negative confirmatory biopsy on reclassification among men on active surveillance. Urology 2017; 107: 184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong LM, Alibhai SM, Trottier G et al. : A negative confirmatory biopsy among men on active surveillance for prostate cancer does not protect them from histologic grade progression. Eur Urol 2014; 66: 406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cary KC, Cowan JE, Sanford M et al. : Predictors of pathologic progression on biopsy among men on active surveillance for localized prostate cancer: the value of the pattern of surveillance biopsies. Eur Urol 2014; 66: 337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turkbey B, Mani H, Aras O et al. : Correlation of magnetic resonance imaging tumor volume with histopathology. J Urol 2012; 188: 1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddiqui MM, Rais-Bahrami S, Turkbey B et al. : Comparison of MR/ultrasound fusion-guided biopsy with ultrasound-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. JAMA 2015; 313: 390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai WS, Gordetsky JB, Thomas JV et al. : Factors predicting prostate cancer upgrading on magnetic resonance imaging-targeted biopsy in an active surveillance population. Cancer 2017; 123: 1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamatakis L, Siddiqui MM, Nix JW et al. : Accuracy of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in confirming eligibility for active surveillance for men with prostate cancer. Cancer 2013; 119: 3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turkbey B, Pinto PA, Mani H et al. : Prostate cancer: value of multiparametric MR imaging at 3 T for detection—histopathologic correlation. Radiology 2010; 255: 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaur S, Harmon S, Mehralivand S et al. : Prospective comparison of PI-RADS version 2 and qualitative in-house categorization system in detection of prostate cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018; doi: 10.1002/jmri.26025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Invivo: UroNav Fusion Biopsy System. Gainesville, Florida: Invivo; 2017. Available at http://www.invivocorp.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/UroNav_Brochure.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kearns JT, Faino AV, Newcomb LF et al. : Role of surveillance biopsy with no cancer as a prognostic marker for reclassification: results from the Canary Prostate Active Surveillance Study. Eur Urol 2018; 73: 706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borofsky S, George AK, Gaur S et al. : What are we missing? False-negative cancers at multiparametric MR imaging of the prostate. Radiology 2018; 286: 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasivisvanathan V, Rannikko AS, Borghi M et al. : MRI-targeted or standard biopsy for prostate-cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiffmann J, Connan J, Salomon G et al. : Tumor volume in insignificant prostate cancer: increasing threshold gains increasing risk. Prostate 2015; 75: 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okoro C, George AK, Siddiqui MM et al. : Magnetic resonance imaging/transrectal ultrasonography fusion prostate biopsy significantly outperforms systematic 12-core biopsy for prediction of total magnetic resonance imaging tumor volume in active surveillance patients. J Endourol 2015; 29: 1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turkbey B, Mani H, Aras O et al. : Prostate cancer: can multiparametric MR imaging help identify patients who are candidates for active surveillance? Radiology 2013; 268: 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehralivand S, Bednarova S, Shih JH et al. : Prospective evaluation of PI-RADS version 2 using the International Society of Urological Pathology prostate cancer grade group system. J Urol 2017; 198: 583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frye TP, George AK, Kilchevsky A et al. : Magnetic resonance imaging-transrectal ultrasound guided fusion biopsy to detect progression in patients with existing lesions on active surveillance for low and intermediate risk prostate cancer. J Urol 2017; 197: 640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore CM, Giganti F, Albertsen P et al. : Reporting magnetic resonance imaging in men on active surveillance for prostate cancer: the PRECISE recommendations—a report of a European School of Oncology Task Force. Eur Urol 2017; 71: 648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walton Diaz A, Shakir NA, George AK et al. : Use of serial multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in the management of patients with prostate cancer on active surveillance. Urol Oncol 2015; 33: 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rayn KN, Bloom JB, Gold SA et al. : Added value of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging to clinical nomograms in predicting adverse pathology in prostate cancer. J Urol 2018; 200: 1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gold SA, Hale GR, Bloom JB et al. : Follow-up of negative MRI-targeted prostate biopsies: when are we missing cancer? World J Urol 2018; doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]