Abstract

Objective

The study aimed to synthesize and characterize pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole hybrids, define their antimicrobial and antifungal activities in vitro, and determine their ability to inhibit the main protease and spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

The ability of the synthesized compounds to inhibit the main protease and spike glycoprotein inhibitory of SARS-CoV-2 was investigated by assessing their mode of binding to the allosteric site of the enzyme using molecular docking. The structures of pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole derivatives synthesized with microwave assistance were confirmed by spectral analysis. Antibacterial and antifungal activities were determined by broth dilution.

Results

Gram-negative bateria (Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) were more sensitive than gram-positive bateria (Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes) to the derivatives. Candida albicans was sensitive to the derivatives at a minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 250 μg/mL. The novel derivatives had better binding affinity (kcal/mol) than nelfinavir, lopinavir, ivermectin, remdesivir, and favipiravir, which are under investigation as treatment for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Compounds 2c, 2e, and 2g formed four hydrogen bonds with the active cavity of the main protease. Many derivatives had good binding affinity for the RBD of the of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein with the formation of up to four hydrogen bonds.

Conclusion

We synthesized novel pyrimidine-linked benzi-midazole derivatives that were potent antimicrobial agents with ability to inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Understanding the pharmacophore features of the main protease and spike glycoprotein offers much scope for the development of more potent agents. We plan to optimize the properties of the derivatives using models in vivo and in vitro so that they will serve as more effective therapeutic options against bacterial and SARS-CoV-2 infections.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor, COVID-19, Molecular docking, Pyrimidine-benzimidazole, Bacteria, Antifungal

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [ 1 ] induced by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has been declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a pandemic [ 2 ]. Coronaviruses have triggered two other epidemics in addition to COVID-19, namely Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS; 2012), and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS; 2002) [ 3 ]. The National Health Commission of China declared in January 20th, 2020 that SARS-CoV-2 infection is transmitted by person-to-person contact [ 4 ]. SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the same family Betacoronaviruses, as those that caused SARS and MERS 5 , 6. The novel coronavirus is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA with a diameter of 80 − 120 nm and 42 large viral RNA genomes [ 7 ]. Coronaviruses are categorized as alpha- (α-COV), beta- (β-COV), gamma- (γ-COV), and delta- (δ-COV) types [ 8 ]. Six of them have infected humans, and SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh after SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV [ 9 ]. Symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection include fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia, fatigue, decreased leukocyte counts, and pneumonia. Although numerous clinical trials have evaluated possible therapies for SARS-CoV-2 infection 10 , 11, treatment is not yet available for COVID-19 [ 12 ].

SARS-CoV-2 invades after binding to host cellular receptors 13 , 14. Host cell receptors and the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 might be viable targets of interest in treating SARS-CoV-2 infection [ 15 ]. Nucleocapsid (N), envelope (E), membrane (M), and spike (S) proteins comprise the structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2 16 , 17. The spike protein consists of an RBD that specifically binds to human angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (hACE-2), which leads to host cell invasion 14 , 17. Much investigative focus is presently directed towards developing specific novel inhibitors of the RBD or hACE-2.

Remdesivir is an approved treatment for COVID-19 [ 18 ]. Lopinavir and nelfinavir might inhibit SARS-CoV-2 viral protease, and a clinical trial of favipiravir is underway for treating pneumonia induced by SARS-CoV-2 [ 17 ]. Favipiravir is a purine nucleoside that disrupts viral RNA synthesis [ 1 ], and ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro [ 19 ]. Therefore, we used remdesivir, nelfinavir, lopinavir, favipiravir, and ivermectin along with the native ligand in the crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease, that is, N3 as reference moieties for molecular docking studies [ 20 ].

Heterocyclic compounds provide scaffolds upon which pharmacophores can assemble to yield potent and selective drugs [ 21 ]. Among these, benzimidazole heterocyclics have attracted attention because they are easy to synthesize and have a wide range of biological activities. The benzimidazole ring is an essential component of vitamin-B12 in the form of 5, 6-dimethyl-l-(alpha-D-ribofuranosyl) benzimidazole [ 22 ]. Various benzimidazole derivatives with human and veterinary anthelmintic [ 23 ], anti-ulcer [ 24 ], cardiotonic [ 25 ], antihypertensive [ 26 ], analgesic[ 27 ], anticonvulsant [ 28 ], anticancer [ 29 ] properties have been developed 30 , 31. Pyrimidines and their derivatives also have anticancer [ 32 ], anxiolytic [ 33 ], antioxidant [ 34 ], antiviral [ 35 ], antifungal [ 36 ], anticonvulsant [ 36 ], antidepressant, and antibacterial properties [ 37 ]. The United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) has approved many purine and pyrimidine derivatives for the management of cancer and viral diseases [ 38 ]. Pyrimidine-fused bicyclic heterocyclic agents have anticancer, antiviral, and many other biological activities.

To date, 147 pyrimidine-fused bicyclic heterocyclic drugs have been approved for clinical application or are currently being clinically administered. The USFDA has authorized 57 of them to treat various diseases, among which, 22 are currently being applied to treat various types of cancer [ 39 ]. The pyrimidine ring system is abundant in nature as substituted and ring-fused compounds and equivalents, such as cytosine, thymine, uracil, thiamine (vitamin B1) and alloxan. It is also found in various synthetic compounds, including barbiturates and the HIV medication, zidovudine. Bacimethrin, a naturally occurring thiamine antimetabolite obtained in 1961 from Bacillus megatherium, is the most basic pyrimidine antibiotic, and it acts against many bacterial infections [ 40 ]. Pyrimidine-fused bicyclic heterocyclic compounds can serve as scaffolds to find new and effective medicines for specific biological targets.

The present study aimed to synthesize and characterize pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole hybrids with antimicrobial and antifungal activity as well as inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 main protease and spike glycoprotein. We screened their antiviral inhibitory action by molecular docking in silico as we were unable to screen them for SARS-CoV-2 activity in vivo due to safety issues. We therefore investigated their antimicrobial and antifungal activities in vitro as preliminary evidence of their biological potential. Molecular docking in silico validates the binding affinity of compounds for target molecules as a docking scores (kcal/mol). This allows the prediction of structural activity relationships between compounds and targets.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Molecular docking

Compounds were screened by molecular docking using the PyRx-Virtual Screening Tool [ 41 ] on a Lenovo ThinkPad with a 64-bit operating system, an Intel(R) CoreTM i5-4300M processor with a base frequency of 2.60 GHz and 4GB RAM.

The structures of approved drugs remdesivir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, invermectin, favipiravir, and native ligand (Spatial Data File [SDF]) were downloaded from the U.S. National Library of Medicine, PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and the structures of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-thiols and novel pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole derivatives were sketched in ChemDraw Ultra 8.0. Energy was minimized using a universal force field (UFF) [ 42 ]. We investigated the binding affinity of the derivatives for the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7) and spike glycoprotein (6VSB). The crystal structures of 6LU7 (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6LU7) and 6VSB (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6VSB) were downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. The native ligand in 6LU7 was N-[(5-methylisoxazol-3-yl) carbonyl] alanyl-L-valyl-N∼1∼-((1R, 2Z)-4-(benzyloxy)-4-oxo-1-{[(3R)-2-oxopyrrolidin-3-yl] methyl} but-2-enyl)-L-leucinamide [ 20 ]. The crystal structure of 6VSB did not indicate a native ligand. Molecular docking proceeded as described [ [43], [44], [45] ]. The interacting amino acid residues in the protein were identified using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer version 19.1.0.18287 (Dassault Systemes, Paris, France) [ 46 ].

2.2. Design of novel pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole hybrids

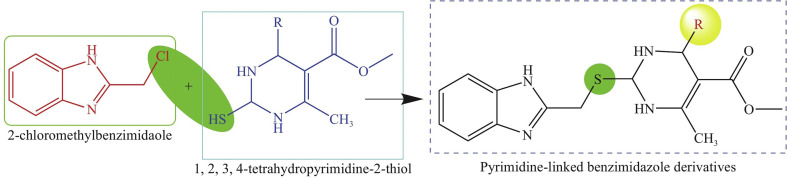

We designed derivatives by merging the 2-(chloromethyl)-1H-benzimidazole moiety with 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-thiol pyrimidine derivatives synthesized via the modified Biginelli reaction. Figure 1 shows the approach used to construct the derivatives. We then compared binding affinities of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-thiols and novel pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole derivatives to determine the significance of merging the two moieties.

Fig. 1.

Synthesis of pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole scaffold

Table 1 shows structures of the pyrimidine derivatives and final novel derivatives obtained by merging benzimidazole with pyrimidine.

Table 1.

Structures of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-thiols and novel pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole derivatives.

2.3. Laboratory procedures

2.3.1. Synthesis of 2-(chloromethyl)-1H-benzimidazole

This procedure is described in the Supplementary material. The yield was 85%. A yellowish-brown product recrystallized from dioxane; m.p., 152 − 154 °C [compared with the literature: 147.8 − 148.2 °C] [ 47 ]. Care was taken while handling 2-(chloromethyl)-1H-benzimidazole because it is a powerful skin and mucous membrane irritant [ 48 ]. Figure 2 shows the reaction scheme for the synthesis of this compound.

Fig. 2.

Synthesis of 2-(chloromethyl)-1H-benzimidazole

2.3.2. Synthesis of pyrimidine derivatives

The modified Biginelli reaction proceeded as described and detailed in the Supplementary material [ 49 ] and generated 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-thiol from ethyl acetoacetate, aldehyde, and thiourea 37 , 50 at 75% − 95% yield (Figure 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Synthesis of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-thiols via modified Biginelli reaction

2.3.3. Merging 2-(chloromethyl)-1H-benzimidazole and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-thiols to synthesize pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole derivatives

We condensed 2-(chloromethyl)-1H-benzimidazole (1.66 g, 0.01 mol and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-thiol (0.01 mol) by heating with potassium hydroxide (KOH) and H2O : acetone (2 : 1) at 50 − 60 °C for 45 min. The reaction mixture was chilled to room temperature, decanted into ice-cold water, filtered, and recrystallized from ethanol (Figure 4 ). The yield was 90% − 95%.

Fig. 4.

Synthesis of novel pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole derivatives

2.4. Calculation of Lipinski rule of five

We applied the Lipinski rule of five that defines the ability of new molecular entities to be useful drugs. In terms of drug development, the rule states that weak absorption or permeation is more likely when the criteria of > 5 H-bond donors, 10 H-bond acceptors, molecular weight > 500, and a measured Log P (MLog P) > 5 are met [ [51], [52], [53], [54] ]. The properties of all derivatives were calculated using the SwissADME online tool (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php).

2.5. Biological activity

Various concentrations of derivatives were prepared in DMSO to assess their antibacterial and antifungal activities against standard strains (Table 2 ) using broth dilution. Bacteria were maintained, and drugs were diluted in nutrient Mueller Hinton broth. The broth was inoculated with 108 colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter of test strains (Institute of Microbial Technology, Chandigarh, India) determined by turbidity. Stock solutions of synthesized derivates (2 mg/mL) were serially diluted for primary and secondary screening. The primary screen included 1000, 500, and 250 μg/mL of synthesized derivatives, then those with activity were further screened at 200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5, and 6.250 μg/mL. A control without antibiotic was subcultured (before inoculation) by spreading one loopful evenly over a quarter of a plate of medium suitable for growing test organisms and incubated at 37 °C overnight. The lowest concentrations of derivatives that inhibited bacterial or fungal growth were taken as minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs). These were compared with the amount of control growth before incubation (original inoculum) to determine MIC accuracy [ [55], [56], [57] ]. The standards for antibacterial activity were gentamycin, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and norfloxacin served, and those for antifungal activity were nystatin and griseofulvin.

Table 2.

Bacterial and fungal strains for activity assay

| Organism | International code |

|---|---|

| Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) | MTCC-443 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gram-negative) | MTCC-1688 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) | MTCC-96 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (Gram-positive) | MTCC-442 |

| Candida albicans | MTCC-227 |

| Aspergillus niger | MTCC-282 |

| Aspergillus clavatus | MTCC-1323 |

3. Results

3.1. Molecular docking

Table 3 shows details of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease and spike glycoprotein according to PDB X-ray structure validation reports.

Table 3.

Crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) and spike glycoprotein used for molecular docking

| Particular | PDB ID |

|

|---|---|---|

| 6LU7 | 6VSB | |

| Title | The crystal structure of COVID-19 main protease in complex with an inhibitor N3 | Prefusion 2019-nCoV spike glycoprotein with one receptor-binding domain up |

| DOI | 10.2210/pdb6LU7/pdb | 10.2210/pdb6VSB/pdb |

| Authors | LIU X, ZHANG B, JIN Z, YANG H, RAO Z | WRAPP D, WANG N, CORBETT KS, GOLDSMITH JA, HSIEH C, ABIONA O, GRAHAM BS, MCLELLAN JS |

| Deposited on | 2020-01-26 | 2020-02-10 |

| Resolution | 2.16 Å (reported) | 3.46 Å (reported) |

| Classification | Viral Protein | Viral Protein |

| Organism(s) | Bat SARS-like coronavirus | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| Expression System | Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) | Homo sapiens |

| Method | X-Ray Diffraction | Electron Microscopy |

Table 4 shows details of the derivatives, their binding affinity (kcal/mol), number of hydrogen bonds formed with targets and active amino acid residues involved in interactions. Data for compounds 1a − 1h (1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-thiols), are provided in Supplementary material.

Table 4.

Details of the synthesized derivatives

| Drug name or derivative code | 6LU7 |

6VSB |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bonds (n) | Active aminoacid residues | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bonds (n) | Active amino acid residues | ||

| Native ligand | − 9 | 7 | Leu141, Phe140, Glu166, Gln192, Pro168, Gln189, Met49, His41, Arg188, Met165, Asp187, His164, Leu27, Thr25, Thr26, Thr24 | − | − | − | |

| Approved drugs for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection | Nelfinavir | − 8 | 3 | Leu27, Cys145, Asn142, Glu166, His164, His41, Tyr54, Asp187, Met165, Gln189, His163, His172, Phe140, Leu141, Ser144, Gly143, Thr26, Thr25 | − 8.7 | 1 | Gly-A:232, Arg-C:355, Phe-C:464 |

| Lopinavir | − 7.3 | 2 | Pro168, Glu166, Asn142, Ser46, Thr25, Thr26, Leu27, Cys145, Met49, His164, Asp187, His41, Arg188, Tyr54, Met165, Gln189 | − 8.5 | 0 | Arg-B:995, Asp-C:994, Thr-B:998, Arg-A:995, Thr-A:998, Tyr-B:756, Thr-C:998 | |

| Ivermectin | − 7.3 | 3 | Asn85, Val186, Arg40, Asn53, Met82 | − 9.1 | 4 | Cys-C:379, Glu-A:988, Val-C:382, Pro-A:987, Val-A:991, Val-B:991, Lys-C:378 | |

| Approved drugs for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection | Remdesivir | − 7 | 8 | Pro168, Leu167, Thr190, His172, Met165,Phe140, His163, Leu141, Ser144, His164, Cys145, Gly143, Met49, Asn142, Glu166, Gln189, Ala191 | − 6.3 | 5 | Asn-B:542, Thr-B:547, Asp-C:745, Leu-C:981, Thr-B:549, Lys-B:386, Leu-C:981 |

| Favipiravir | − 5.7 | 4 | Gln127, Asp295, Phe08, Asn151, Phe112, Phe294, Thr292, Thr111, Gln110, Ile106 | − 5.2 | 4 | Asp-A:994, Phe-C:970, Arg-C:995, Thr-C:998, Gly-C:999 | |

| Novel pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole hybrids | 2a | − 6.6 | 1 | Thr190, Met165, His41, Glu166, His164, Met49, Cys145, Thr26, Gly143, Leu27, Thr25, Ser144, Leu141, Gln189 | − 7.2 | 3 | Thr-B:998, Thr-A:998, Asp-B:994, Tyr-B:756 |

| 2b | − 7.1 | 2 | Pro168, Asn142, His41, Met49, Asp187, Arg188, Tyr54, Met165, Gln189, Cys145, Leu167 | − 7.9 | 2 | Asp-B:994, Thr-B:998 | |

| 2c | − 7.8 | 4 | His163, Asn142, His164, His41, Met165, Asp187, Arg188, Val186, Gln192, Thr190, Pro168, Gln189, Cys145, Met49, Thr25, Thr26, Leu27, Gly143, Leu141, Ser144 | − 8.5 | 3 | Asn-B:978, Leu-B:977, Thr-A:547, Val-B:976, Leu-A:546 | |

| 2d | − 7.6 | 3 | Thr25, Leu27, Thr26, Gly143, Leu141, Gln189, Thr190, Met165, Glu166, His164, Arg188, Asp187, Met49 | − 8.4 | 3 | Thr-C:998, Asp-B:994, Arg-A:995, Thr-B:998, Tyr-C:756 | |

| 2e | − 7.4 | 4 | Tyr54, Asp187, Met49, His164, Asn142, Leu167, Pro168, Thr190, Gln192, Glu166, Gln189, Met165, Arg188, His41 | − 8.8 | 1 | Thr-C:998, Tyr-C:756, Thr-B:998, Arg-A:995, Asp-B:994, Arg-C:995, Arg-B:995 | |

| Novel pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole hybrids | 2f | − 8.1 | 1 | His41, His164, Met165, Met49, Tyr54, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190, Gln192, Leu167, Pro168, Leu141, Asn142, Cys145, Ser144, Gly143, Leu27 | − 8.2 | 3 | Thr-B:415, Gly-B:416, Gln-B:414, Pro-C:384, Glu-A:988, Asp-A:985, Thr-C:385 |

| 2g | − 7.2 | 4 | Cys145, His41, Met165, His164, Met49, Gln189, Glu166, Leu167, Pro168, Asn142, Leu141, Phe140, Arg188, Tyr54, His163, Asp187 | − 8.3 | 4 | Thr-A:998, Arg-A:995, Thr-C:998, Tyr-C:756, Thr-B:998, Thr-C:998 | |

| 2h | − 8.0 | 2 | Met165, Cys145, Ser144, Met49 | − 8.3 | 1 | Tyr-B:756, Thr-C:998, Thr-B:998. Tyr-C:756 | |

Table 5 shows the two- and three-dimensional (2D and 3D) binding positions of the derivatives. These enabled us to predict which atoms and/or groups in a ligand are involved in interactions with amino acid residues in target derivatives. Details of 2D and 3D-docking of compounds 1a − 1h are provided in the Supplementary material.

Table 5.

2D and 3D docking positions of drugs targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease and RBD of spike glycoprotein.

Table 6 shows changes in the number of hydrogen bonds formed and binding affinity before and after merging with benzimidazole.

Table 6.

Affinity and hydrogen bonds formed after pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole hybrids bound to SARS-CoV-2 main protease

| Code | 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-thiols |

Code | Pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole hybrids |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bonds (n) | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bonds (n) | ||

| 1a | − 4.4 | 4 | 2a | − 6.6 | 1 |

| 1b | − 6.1 | 1 | 2b | − 7.1 | 2 |

| 1c | − 5.8 | 2 | 2c | − 7.8 | 4 |

| 1d | − 6.1 | 3 | 2d | − 7.6 | 3 |

| 1e | − 6.1 | 3 | 2e | − 7.4 | 4 |

| 1f | − 5.9 | 1 | 2f | − 8.1 | 1 |

| 1g | − 6.1 | 1 | 2g | − 7.2 | 4 |

| 1h | − 6.3 | 1 | 2h | − 8.0 | 2 |

3.2. Chemistry

Spectral characterization revealed the formation of pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole derivatives. The chemistry, melting points, physical properties, and IR spectra are provided in the Supplementary material.

3.2.1. 2-(chloromethyl)-1H-benzimidazole

Molecular formula, C8H7ClN2; molecular weight, 166.61; appearance, yellowish brown; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; elemental analysis, C, 57.67; H, 4.23; Cl, 21.28; N, 16.81; Log P, 2.11; yield, 90%; m.p., 152 − 154 °C; IR: aromatic, 933 and 842 cm−1; halogen, 642 cm−1; NH bending, 1600 cm−1; NH stretching, 3 300 − 3 400 cm−1; CH bending, 700 and 842 cm−1; CH stretching, 3 084 cm−1; C=C, 1 650 cm−1.

3.2.2. Ethyl 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2-mercapto-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (1a)

Molecular formula, C8H14N2O2,S; molecular weight, 198.24; appearance, light pink powder; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 198.05 (100.0%), 199.05 (9.6%), 200.04 (4.5%); elemental analysis, C, 48.47; H, 5.08; N, 14.13; O, 16.14; S, 16.17; Log P, 1.66; yield, 80%; m.p., 213 − 215 °C; IR: NH bending, 1600 cm−1; NH stretching, 3 315 cm−1; CH bending, 960 cm−1; CH stretching, 3030 cm−1; ester group, 1710 cm−1; SH stretching, 2524 cm−1; C-S stretching, 680 cm−1; aromatic, 690 cm−1.

3.2.3. Ethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2-mercapto-6-methyl-4-phenylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (1b)

Molecular formula, C14H18N2O2S; molecular weight, 274.34; appearance, milky white crystals; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 274.08 (100.0%), 275.08 (16.2%), 276.07 (4.5%), 276.08 (1.7%); elemental analysis, C, 61.29; H, 5.14; N, 10.21; O, 11.66; S, 11.69; Log P, 3.76; yield 85%; m.p., 203 − 205 °C; IR: NH bending 1654 cm−1; NH stretching, 3332 cm−1; CH bending, 869 cm−1; CH stretching, 3180 cm−1; ester group, 1700 cm−1; aromatic, 700 cm−1; SH stretching, 2582 cm−1; C-S stretching 692 cm−1.

3.2.4. Ethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-4-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-2-mercapto-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (1c)

Molecular formula, C14H18N2O3S; molecular weight, 290.34; appearance, prismatic white crystals; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 290.07 (100.0%), 291.08 (15.4%), 292.07 (4.6%), 292.08 (1.8%), 291.07 (1.5%; elemental analysis, C, 57.92; H, 4.86; N, 9.65; O, 16.53; S, 11.04; Log P, 3.37; yield, 77%; m.p., 201 − 203 °C; IR: NH bending, 1581 cm−1; NH stretching, 3300 cm−1; CH bending, 756 cm−1; CH stretching, 3003 cm−1; ester group, 1751 cm−1; hydroxy group, 3600 cm−1; aromatic o-disubstituted, 730 cm−1; SH stretching, 2600 cm−1; C-S stretching, 650 cm−1.

3.2.5. Ethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-2-mercapto-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (1d)

Molecular formula, C14H18N2O3S; molecular weight, 290.34; appearance, light brown powder; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 290.07 (100.0%), 291.08 (15.4%), 292.07 (4.6%), 292.08 (1.8%), 291.07 (1.5%); elemental analysis, C, 57.92; H, 4.86; N, 9.65; O, 16.53; S, 11.04; Log P, 3.37; yield, 79%; m.p., 179 − 181 °C; IR: -NH bending, 1 610 cm−1; NH stretching, 3319 cm−1; CH bending, 866 cm−1; CH stretching 3150 cm−1; ester group 1700 cm−1; hydroxy group, 3600 cm−1 aromatic m-disubstituted, 680 and 788 cm−1; SH stretching, 2500 cm−1; C-S stretching, 630 cm−1.

3.2.6. Ethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-mercapto-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (1e)

Molecular formula, C14H14N2O3S; molecular weight, 290.34; appearance, off-white powder; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 290.07 (100.0%), 291.08 (15.4%), 292.07 (4.6%), 292.08 (1.8%), 291.07 (1.5%); elemental analysis, C, 57.92; H, 4.86; N, 9.65; O, 16.53; S, 11.04; Log P, 3.37; yield, 85%; m.p., 225 − 227 °C; IR: NH bending, 1581 cm−1; NH stretching 3400 cm−1; SH bending, 825 cm−1; SH stretching 3016 and 3196 cm−1; ester group 1689 cm−1; hydroxy group 3502 cm−1 aromatic p-disubstituted, 825 cm−1; SH stretching, 2561 cm−1; C-S stretching, 642 cm−1.

3.2.7. Ethyl-4-(2-chlorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2-mercapto-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (1f)

Molecular formula, C14H17ClN2O2S; molecular weight, 308.78; appearance, yellowish white sticky product; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 308.04 (100.0%), 310.04 (32.6%), 309.04 (16.9%), 311.04 (5.9%), 310.03 (4.5%), 312.03 (1.5%), 310.05 (1.1%); elemental analysis, C, 54.46; H, 4.24; Cl, 11.48; N, 9.07; O, 10.36; S, 10.38; Log P, 4.31; yield, 87%; m.p. 192 − 194 °C; IR: NH bending, 1580 cm−1; NH stretching, 3350 cm−1; CH bending, 767 cm−1; CH stretching, 3100 cm−1; ester group, 1724 cm−1; halogen group, 646 cm−1; aromatic o-disubstituted, 767 cm−1; SH stretching, 2349 cm−1; C-S stretching, 646 cm−1.

3.2.8. Ethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2-mercapto-4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (1g)

Molecular formula, C15H20N2O3S; molecular weight, 304.36; appearance, white crystals; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 304.09 (100.0%), 305.09 (18.1%), 306.08 (4.5%), 306.09 (2.1%); elemental analysis, C, 59.19; H, 5.30; N, 9.20; O, 15.77; S, 10.54; Log P, 3.63; yield, 92%; m.p., −199 − 201 °C; IR: NH bending, 1581 cm−1; NH stretching, 3319 cm−1; CH bending, 767 cm−1; CH stretching, 3150 cm−1; ester group, 1710 cm−1; ether group, 1186 cm−1; aromatic p-disubstituted, 790 cm−1; SH stretching, 2500 cm−1; C-S stretching, 653 cm−1.

3.2.9. Ethyl-4-cinnamyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2-mercapto-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (1h)

Molecular formula, C17H22N2O2S; molecular weight, 314.4; appearance, white crystals; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 314.11 (100.0%), 315.11 (20.0%), 316.10 (4.5%), 316.12 (1.6%); Elemental Analysis, C, 64.94; H, 5.77; N, 8.91; O, 10.18; S, 10.20; Log P, 4.55; yield, 82%; m.p., 200 − 202 °C; IR, NH bending, 1595 cm−1; NH stretching, 3400 cm−1; CH bending, 852 cm−1; CH stretching, 3150 cm−1; ester group, 1703 cm−1; C=C, 1670 cm−1; aromatic, mono-substituted, 700 and 770 cm−1; SH stretching, 2600 cm−1; SH stretching, 661 cm−1.

3.2.10. Ethyl-2-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)methylthio)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (2a)

Molecular formula, C16H20N4O2S; molecular weight, 328.39; appearance, yellowish brown; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 328.10 (100.0%), 329.10 (19.7%), 330.10 (5.3%), 330.11 (1.5%); elemental analysis, C, 58.52; H, 4.91; N, 17.06; O, 9.74; S, 9.76; Log P, 3.07; yield, 91%; m.p., 172 − 174 °C; IR: NH bending, 1546 cm−1; NH stretching, 3313 cm−1; CH bending, 750 cm−1; CH stretching, 3034 cm−1; ester group, 1700 cm−1; C=C, 1600 cm−1; aromatic, 750 cm−1; -C-S-C, 750 cm−1; C-S stretching, 680 cm−1.

3.2.11. Ethyl-2-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)methylthio)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-methyl-4-phenylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (2b)

Molecular formula, C22H24N4O2S; molecular weight, 404.48; appearance, yellowish brown; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 404.13 (100.0%), 405.13 (26.1%), 406.13 (5.5%), 406.14 (2.8%), 407.13 (1.1%); elemental analysis, C, 65.33; H, 4.98; N, 13.85; O, 7.91; S, 7.93; Log P, 5.17; yield, 93%; m.p., 142 − 144 °C; IR, NH bending, 1600 cm−1; NH stretching, 3313 cm−1; CH bending, 842 cm−1; CH stretching, 3061 cm−1; ester group, 1700 cm−1; C=C, 1600 cm−1; aromatic, 700 and 742 cm−1; C=N group, 1644 cm−1; -C-S-C, 742 cm−1; C-S stretching, 700 cm−1.

3.2.12. Ethyl-2-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)methylthio)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-4-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (2c)

Molecular formula, C22H24N4O3S; molecular weight, 420.48; appearance, yellowish brown; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 420.13 (100.0%), 421.13 (24.1%), 422.12 (4.5%), 422.13 (3.9%), 421.12 (2.3%), 423.12 (1.1%); elemental analysis, C, 62.84; H, 4.79; N, 13.32; O, 11.41; S, 7.63; Log P, 4.78; yield, 95%; m.p., 152 − 154 °C; IR: NH bending, 1593 cm−1; NH stretching, 3313 cm−1; CH bending, 700 cm−1; CH stretching, 3055 cm−1; ester group, 1764 cm−1; C=C, 1600 cm−1; aromatic o-disubstituted, 700 and 746 cm−1; C=N group, 1670 cm−1; C-S-C, 746 cm−1; C-S stretching, 600 cm−1.

3.2.13. Ethyl-2-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)methylthio)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (2d)

Molecular formula, C22H24N4O3S; molecular weight, 420.48; appearance, yellowish brown; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 420.13 (100.0%), 421.13 (24.1%), 422.12 (4.5%), 422.13 (3.9%), 421.12 (2.3%), 423.12 (1.1%); elemental analysis, C, 62.84; H, 4.79; N, 13.32; O, 11.41; S, 7.63; Log P, 4.78; yield, 95%; m.p., 223 − 225 °C; IR: NH bending, 1595 cm−1; NH stretching, 3300 cm−1; CH bending, 700 cm−1; CH stretching, 3050 cm−1; ester group, 1700 cm−1; C=C, 1600 cm−1; aromatic m-disubstituted, 700 and 742 cm−1; C=N group, 1595 cm−1; -C-S-C, 742 cm−1; C-S stretching, 700 cm−1.

3.2.14. Ethyl-2-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)methylthio)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (2e)

Molecular formula, C22H24N4O3S; molecular weight, 420.48; appearance, yellowish brown; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 420.13 (100.0%), 421.13 (24.1%), 422.12 (4.5%), 422.13 (3.9%), 421.12 (2.3%), 423.12 (1.1%); elemental analysis, C, 62.84; H, 4.79; N, 13.32; O, 11.41; S, 7.63; Log P, 4.78; yield, 96%; m.p., 138 − 140 °C; IR: NH bending, 1598 cm−1; NH stretching, 3400 cm−1; CH bending, 850 cm−1; CH stretching, 3062 cm−1; ester group, 1700 cm−1; C=C, 1598 cm−1; aromatic p-disubstituted, 742 cm−1; C-S-C, 742 cm−1; C-S stretching, 690 cm−1.

3.2.15. Ethyl-2-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)methylthio)-4-(2-chlorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (2f)

Molecular formula, C22H23ClN4O2S; molecular weight, 438.93; appearance, yellowish brown; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 438.09 (100.0%), 440.09 (37.0%), 439.10 (24.1%), 441.09 (9.5%), 440.10 (3.2%), 439.09 (2.3%), 442.08 (1.4%); elemental analysis, C, 60.20; H, 4.36; Cl, 8.08; N, 12.76; O, 7.29; S, 7.31; Log P, 5.73; yield, 90%; m.p., 106 − 108 °C; IR: NH bending, 1571 cm−1; NH stretching, 3298 cm−1; CH bending, 700 cm−1; CH stretching, 2950 cm−1; ester group, 1700 cm−1; C=C, 1470 cm−1; C=N group, 1691 cm−1; halogen, 700 cm−1; aromatic o-disubstituted, 752 cm−1; -C-S-C, 752 cm−1; C-S stretching, 650 cm−1.

3.2.16. Ethyl-2-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)methylthio)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (2g)

Molecular formula, C23H26N4O3S; molecular weight, 434.51; appearance, yellowish brown; soluble in ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 434.14 (100.0%), 435.14 (27.2%), 436.14 (5.1%), 436.15 (3.7%), 437.14 (1.2%); elemental analysis, C, 63.58; H, 5.10; N, 12.89; O, 11.05; S, 7.38; Log P, 5.04; yield, 92%; m.p., 148 − 150 °C; IR: NH bending, 1590 cm−1; NH stretching, 3300 cm−1; CH bending, 833 cm−1; CH stretching, 3150 cm−1; ester group, 1699 cm−1; ether, 1184 cm−1; C=C, 1450 cm−1; C=N group, 1680 cm−1; aromatic p-disubstituted, 800 cm−1; C-S-C, 744 cm−1; C-S stretching, 650 cm−1.

3.2.17. Ethyl-2-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)methylthio)-4-cinnamyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-methylpyrimidine-5-carboxylate (2h)

Molecular formula, C25H28N4O2S; molecular weight, 444.55; appearance, yellowish brown; solubility, ethanol, acetone, benzene; m/e ratio, 444.16 (100.0%), 445.17 (27.4%), 446.16 (5.2%), 446.17 (4.0%), 445.16 (2.3%), 447.16 (1.2%); elemental analysis, C, 67.54; H, 5.44; N, 12.60; O, 7.20; S, 7.21; Log P, 5.04; yield, 90%; m.p., 180 − 182 °C; IR: NH bending, 1564 cm−1; NH stretching, 3250 cm−1; CH bending, 850 cm−1; CH stretching, 3059 cm−1; ester group, 1700 cm−1; C=C, 1480 cm−1; C=N group, 1680 cm−1; aromatic mono-substituted, 694 cm−1; -C-S-C, 746 cm−1; C-S stretching, 694 cm−1.

3.3. Antimicrobial and antifungal activity

The antimicrobial susceptibility of all synthesized pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole derivatives was tested. Table 7 shows the MIC and minimum fungicidal concentrations (MFCs). The MIC of derivative 2a against E. coli was 62.5 μg/mL, which was much more potent than ampicillin, whereas derivatives 2c, 2e, and 2f were equipotent at a MIC of 100 μg/mL. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was sensitive to all synthesized derivatives at 62.5, 100, and 250 μg/mL, but not to ampicillin. Staphylococcus aureus was sensitive to derivatives 2a, 2b, 2d, 2e, and 2g at 200, 100, 100, 100, and 200 μg/mL, respectively, indicating that they were more potent than ampicillin, which was active at 250 μg/mL. The MICs of derivatives 2b and 2f were both 100 μg/mL, and these compounds were equipotent against S. pyogenes. Derivatives 2b, 2c, 2d, 2e, and 2f exerted more effective fungicidal activity against C. albicans compared with griseofulvin with MICs of 250 and 500 μg/mL, respectively.

Table 7.

Minimum inhibitory and fungicidal concentrations of standard drugs and synthesized derivatives (μg/mL)

| Drug name or code | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | S. aureus | S. pyogenes | C. albicans | A. niger | A. clavatus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | 62.5 | 100 | 200 | 200 | 1000 | > 1000 | > 1000 |

| 2b | 125 | 62.5 | 100 | 100 | 250 | 500 | 500 |

| 2c | 100 | 100 | 250 | 250 | 250 | > 1000 | > 1000 |

| 2d | 250 | 100 | 100 | 250 | 250 | > 1000 | > 1000 |

| 2e | 100 | 250 | 100 | 250 | 250 | > 1000 | > 1000 |

| 2f | 100 | 62.5 | 250 | 200 | 250 | 500 | 500 |

| 2g | 250 | 100 | 200 | 100 | 500 | 250 | 250 |

| 2h | 250 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 250 | 250 |

| Gentamycin | 0.05 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Ampicillin | 100 | − | 250 | 100 | NA | NA | NA |

| Chloramphenicol | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | NA | NA | NA |

| Ciprofloxacin | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 | NA | NA | NA |

| Norfloxacin | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | NA | NA | NA |

| Nystatin | NA | NA | NA | NA | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Griseofulvin | NA | NA | NA | NA | 500 | 100 | 100 |

NA represents not applicable.

We used nystatin and griseofulvin as the standard antifungals against A. niger, C. albicans, and A. clavatus. Table 7 shows the MFCs. Derivatives 2b, 2c, 2d, 2e, and 2f exerted fungicidal activity against, C. albicans was sensitive at a MIC of 250 μg/mL compared with griseofulvin at 500 μg/mL.

3.4. Lipinski rule of five

None of the derivatives violated the rule of 5, indicating good absorption or permeation of the derivatives (Table 8 ).

Table 8.

Lipinski rule of five for all synthesized derivatives

| Drug name or code | Molecular formula | Lipinski rule of five |

Violation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight | HBA | HBD | Log P | |||

| Native ligand (6LU7) | C35H48N6O8 | 680.7 | 9 | 5 | 0.38 | 1 |

| Nelfinavir | C32H45N3O4S | 567.8 | 5 | 4 | 3.20 | 1 |

| Lopinavir | C37H48N4O5 | 628.8 | 5 | 4 | 2.93 | 1 |

| Ivermectin | C47H72O14 | 875.1 | 14 | 3 | 1.25 | 2 |

| Remdesivir | C27H35N6O8P | 602.6 | 12 | 4 | 0.18 | 2 |

| Favipiravir | C5H4FN3O2 | 157.1 | 4 | 2 | − 1.30 | 0 |

| 2a | C16H20N4O2S | 332.4 | 4 | 3 | 1.23 | 0 |

| 2b | C22H24N4O2S | 408.5 | 4 | 3 | 2.39 | 0 |

| 2c | C22H24N4O3S | 424.5 | 5 | 4 | 1.86 | 0 |

| 2d | C22H24N4O3S | 424.5 | 5 | 4 | 1.86 | 0 |

| 2e | C22H24N4O3S | 424.5 | 5 | 4 | 1.86 | 0 |

| 2f | C22H23ClN4O2S | 442.9 | 4 | 3 | 2.87 | 0 |

| 2g | C23H26N4O3S | 438.5 | 5 | 3 | 2.07 | 0 |

| 2h | C25H28N4O2S | 448.5 | 4 | 3 | 2.95 | 0 |

4. Discussion

We applied molecular docking to compare the ability of pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole hybrids to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 main protease and the RBD of spike glycoprotein with approved drugs and native ligands. The binding affinity of several derivatives was similar to that of approved drugs. The formation of a hydrogen bonds with target molecules results in inhibition, but binding affinity can be increased by van der Waals forces, Pi-Pi, and hydrophobic interactions. Thus, optimal inhibitors should comprise ligands that form hydrogen bonds with targets. For example, the binding affinity of remdesivir for the main protease is − 7 kcal/mol, which is much lower than that of approved drugs, but it forms about eight hydrogen bonds with target, which confers better inhibitory activity than these drugs. This could explain why it has been accepted for clinical trials for the management of COVID-19. Our novel derivatives also formed hydrogen bonds with their targets, indicating inhibitory potency towards the SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

The binding affinity of our novel derivatives for the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein was as good that that of the approved drugs. The binding affinity of ivermectin for the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein is − 9.1 kcal/mol and it forms four hydrogen bonds. It interacts with Cys-C at 379, Glu-A at 988, Val-C at 382, Pro-A at 987, Val-A at 991, Val-B at 991, and Lys-C at 378. The binding affinity of remdesivir is − 6.3 kcal/mol and it forms five hydrogen bonds with the RBD. It interacts with Asn-B at 542, Thr-B at 547, Asp-C at 745, Leu-C at 981, Thr-B at 549, Lys-B at 386, and Leu-C at 981. Favipiravir forms four hydrogen bonds with the RBD and its binding affinity is − 5.2 kcal/mol. It interacts with Asp-A at 994, Phe-C at 970, Arg-C at 995, Thr-C at 998, and Gly-C at 999. Ivermectin, remdesivir, and favipiravir are currently applied to treat SARS-CoV-2 infection. Several of our derivatives have good binding affinity and formed up to four hydrogen bonds with the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein.

Antimicrobial screening revealed that compounds with an aromatic ring at the R position were more potent than ampicillin, which is the standard antimicrobial against P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and S. pyogenes. This might be attributed to the polar effect of the aromatic rings. Derivatives without substitution at the R position were more potent than ampicillin against E. coli and S. aureus, which might have been due to being smaller and having a low molecular weight. Compounds with phenyl, hydroxy phenyl, and chlorophenyl substitutions at the R position were more active than griseofulvin against C. albicans.

The drug-likeliness of ligands was assessed using Lipinski's rule of five in order to determine the pharmacokinetic characteristics of the synthesized ligands. All ligands were recognized as drug-like compounds and without any structural caution the physicochemical filter was passed through. The virtual screening method has the advantage of being able to produce ligands with high predicted binding affinities for completely new protein sequences. Here from the binding affinity, we can choose few potential ligands for the further optimization and development of novel anti-SARS-CoV-2 drugs. Compound 2c, 2d, 2e, 2f, 2g, and 2h exhibited good binding affinity with main protease and RBD of spike glycoprotein, also formed enough number of hydrogen bonds. We can choose these ligands for further optimization and validation, in order to search for more novel compounds for the treatment of COVID-19.

We determined changes in the binding affinity of pyrimidines after combining them with benzimidazole to predict the contributions of functional groups. The numbers of hydrogen bonds also changed, indicating the significance of merging benzimidazole with pyrimidine.

The docking scores of almost all derivatives indicated that binding affinity increased when merged with benzimidazole. Compound 1a formed four hydrogen bonds and 2a formed only one with the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Compounds 2c, 2d, 2e, 2f, and 2 g had better binding affinity and formed more hydrogen bonds than compound 2b, indicating that synthesized derivatives with different substituted benzaldehydes, preferably at the ortho and meta positions, would generate more potent derivatives. The binding affinity of compound 2h increased and it formed two hydrogen bonds, indicating that increasing the chain length of the R group increases potency. We speculated that substitution with cinnamaldehyde will increase binding affinity as well as the number of hydrogen bonds. The information rendered by molecular docking study improved understanding of the structural requirements for developing more novel blockers of SARS-CoV-2 main protease and inhibitors of the RBD of spike glycoprotein. Figure 5 shows the predicted pharmacophore features of each compound.

Fig. 5.

Predicted pharmacophore features of novel derivatives for further optimization

5. Conclusion

We could not assess the ability of our derivatives to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro due to safety reasons. However, we investigated their antimicrobial and antifungal properties as preliminary biological evidence. We found that pyrimidine-linked benzimidazole derivatives at specific concentrations were more effective than the standard ampicillin against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Some derivatives were more active at higher concentrations than standard drugs. Gram-negative abcteria E. coli and P. aeruginosa were more sensitive to the novel derivatives than gram-positive bacteria S. aureus and S. pyogenes. C. albicans was sensitive to the derivatives at a MFC of 250 μg/mL.

The molecular docking method was used to examine whether any possible ligands had potential interactions with the main protease and RBD of spike glycoprotein. Despite certain disadvantages, such as the use of in vitro conditions rather than in vivo conditions, molecular docking enables researchers to make more accurate decisions in a smaller duration. We developed eight of derivatives that had binding affinity and potential anti SARS-CoV-2 activities that exceeded those of currently approved drugs for treating COVID-19 infection. However, understanding the pharmacophore features of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease and the RBD of spike glycoprotein provides much scope to generate more potent derivatives. Optimizing the properties of these derivatives in models in vivo and in vitro, will lead to more effective options to fight SARS-CoV-2 infection. Because of the critical global COVID-19 situation, we believe that extensive investigation is imperative to acquire a deeper understanding of SARS-CoV-2 and generate effective agents to treat and prevent infection worldwide. At present, a single lead could be a game changer.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Liu C., Zhou Q., Li Y. Research and development on therapeutic agents and vaccines for COVID-19 and related human coronavirus diseases. ACS Central Science. 2020;6(3):315–331. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh A.K., Singh A., Shaikh A. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 with or without diabetes: a systematic search and a narrative review with a special reference to India and other developing countries. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews. 2020;14(3):241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elfiky A.A. Ribavirin, remdesivir, sofosbuvir, galidesivir, and tenofovir against SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp): a molecular docking study. Life Science. 2020:117592. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu D., Wu T., Liu Q., Yang Z. The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: what we know. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;94:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng O.W., Tan Y.J. Understanding bat SARS-like coronaviruses for the preparation of future coronavirus outbreaks - implications for coronavirus vaccine development. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2017;13(1):186–189. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1228500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim I.M., Abdelmalek D.H., Elshahat M.E. COVID-19 spike-host cell receptor GRP78 binding site prediction. Journal of Infection. 2020;80(2):554–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ul Qamar M.T., Alqahtani S.M., Alamri M.A. Structural basis of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and anti-COVID-19 drug discovery from medicinal plants. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2020;10(4):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020;323(18):1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L., Wang Y., Ye D. Review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) based on current evidence. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2020;55(6):105948. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen C., Yu N., Cai S. Quantitative computed tomography analysis for stratifying the severity of coronavirus disease 2019. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2020;10(2):123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X., Geng M., Peng Y. Molecular immune pathogenesis and diagnosis of COVID-19. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2020;10(2):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortegiani A., Ingoglia G., Ippolito M. A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. Journal of Critical Care. 2020;57:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maginnis M.S. Virus-receptor interactions: the key to cellular invasion. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2018;430(17):2590–2611. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourgonje A.R., Abdulle A.E., Timens W. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), SARS-CoV-2 and the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Journal of Pathology. 2020;251(3):228–248. doi: 10.1002/path.5471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothan H.A., Byrareddy S.N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2020;109:102433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo Y.R., Cao Q.D., Hong Z.S. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Military Medical Research. 2020;7(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musarrat F., Chouljenko V., Dahal A. The anti-HIV drug nelfinavir mesylate (viracept) is a potent inhibitor of cell fusion caused by the SARSCoV-2 spike (S) glycoprotein warranting further evaluation as an antiviral against COVID-19 infections. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020;92(10):2087–2095. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shih Weichung J., Chen Y.A.O.T.X. Data Monitoring for the Chinese clinical trials of remdesivir in treating patients with COVID-19 during the pandemic crisis. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science. 2020;54(5):1–20. doi: 10.1007/s43441-020-00159-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caly L., Druce J.D., Catton M.G. The FDA-approved drug ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Antiviral Research. 2020;178:104787. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cragg G.M., Newman D.J. Natural products: a continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2013;1830(6):3670–3695. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alaqeel S.I. Synthetic approaches to benzimidazoles from o-phenylenediamine: a literature review. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society. 2017;21(2):229–237. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shahare M.B., Kadam V.J., Jagdale D.M. Synthesis and evaluation of novel anthelmentic benzimidazole derivatives. International Journal of Research in Pharmacy and Chemistry. 2012;2(1):132–136. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patil A., Ganguly S., Surana S. A systematic review of benzimidazole derivatives as an antiulcer agent. Rasayan Journal of Chemistry. 2008;1(3):447–460. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solaro R.J., Ruegg J.C. Stimulation of Ca++ binding and ATPase activity of dog cardiac myofibrils by AR-L 115BS, a novel cardiotonic agent. Circulation Research. 1982;51(3):290–294. doi: 10.1161/01.res.51.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bansal Y., Silakari O. The therapeutic journey of benzimidazoles: a review. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;20(21):6208–6236. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faruk A., Dey B.K., Chakraborty A. Synthesis, characterization and pharmacological screening of some novel benzimidazole derivatives. International Research Journal of Pharmacy. 2014;5(4):325–331. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chimirri A., De Sarro A., De Sarro G. Synthesis and anticonvulsant properties of 2, 3, 3a, 4-tetrahydro-1H-pyrrolo[1, 2-a]benzimidazol-1-one derivatives. Il Farmaco. 2001;56(11):821–826. doi: 10.1016/s0014-827x(01)01147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akhtar W., Khan M.F., Verma G., Shaquiquzzaman M., Rizvi M.A., Mehdi S.H. Therapeutic evolution of benzimidazole derivatives in the last quinquennial period. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2017;126:705–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katritzky A, Ramsden C, Joule J, et al. Handbook of Heterocyclic Chemistry. 3rd edition. Elsevier, 2010: 1010.

- 31.Mayura K., Charan S. Benzimidazole: an important biological heterocyclic scaffold. Journal of Current Pharma Research. 2014;4(2):1159–1167. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aziz M.A., Serya R.A.T., Lasheen D.S. Furo[2, 3-d]pyrimidine based derivatives as kinase inhibitors and anticancer agents. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2016;2(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.goodacre S.C., Street L.J., Hallett D.J. Imidazo[1, 2-a]pyrimidines as functionally selective and orally bioavailable GABAAα2/α3 binding site agonists for the treatment of anxiety disorders. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;49(1):35–38. doi: 10.1021/jm051065l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Padmaja A., Payani T., Reddy G.D. Synthesis, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of substituted pyrazoles, isoxazoles, pyrimidine and thioxopyrimidine derivatives. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;44(11):4557–4566. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Undheim K., Benneche T. Pyrimidines and their benzo derivatives. Comprehensive Heterocyclic Chemistry II. 1996;6:93–231. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dansena H., Hj D., Chandrakar K. Pharmacological potentials of pyrimidine derivative: a review. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2015;8(4):171–177. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohana Roopan S., Sompalle R. Synthetic chemistry of pyrimidines and fused pyrimidines: a review. Synthetic Communication. 2016;46(8):645–672. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gordon W.G., John A.J. A critical review of the 2005 literature preceded by two chapters on current heterocyclic topics. Progress in Heterocyclic Chemistry. 2007;18:126–149. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang S., Yuan X.H., Wang S.Q. FDA-approved pyrimidine-fused bicyclic heterocycles for cancer therapy: synthesis and clinical application. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2021;214:113218. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lagoja I.M. Pyrimidine as constituent of natural biologically active compounds. Chemistry & Biodiversity. 2005;2(1):1–50. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200490173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dallakyan S., Olson A.J. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2015;1263(1263):243–250. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rappé A.K., Casewit C.J., Colwell K.S. UFF, a full periodic table force field for molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1992;114(25):10024–10035. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chaudhari R.N., Khan S.L., Chaudhary R.S. Β-Sitosterol: isolation from muntingia calabura linn bark extract, structural elucidation and molecular docking studies as potential inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (COVID-19) Asian Journal Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2020;13(5):204–209. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan S.L., Siddiui F.A. Beta-Sitosterol: as immunostimulant, antioxidant and inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Archives of Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2020;2(1):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan S.L., Siddiqui F.A., Jain S.P. Discovery of potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) main protease (Mpro) from Nigella Sativa (Black Seed) by molecular docking study. Coronaviruses. 2021;2(3):384–402. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dassault Systèmes. Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA, Discovery Studio Modeling Environment. 2017. https://www.3dsbiovia.com/about/citations-references/

- 47.Gutierréz-Hernández A., Galván-Ciprés Y., Domínguez-Mendoza E.A. Design, synthesis, antihyperglycemic studies, and docking simulations of benzimidazole-thiazolidinedione hybrids. Journal of Chemistry. 2019;2019:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albert B., Allan R.D. The preparation of 2-alkylaminobenzimidazoles. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1939;14(17):14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen Z.L., Xu X.P., Ji S.J. Brønsted base-catalyzed one-pot three-component Biginelli-type reaction: an efficient synthesis of 4,5,6-triaryl-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-one and mechanistic study. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2010;75(4):1162–1167. doi: 10.1021/jo902394y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Durga Devi D., Manivarman S., subashchandrabose S. Synthesis, molecular characterization of pyrimidine derivative: a combined experimental and theoretical investigation. Karbala International Journal of Modern Science. 2017;3(1):18–28. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baell J., Congreve M., Leeson P. Ask the experts: past, present and future of the rule of five. Future Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;5(7):745–752. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giménez B.G., Santos M.S., Ferrarini M. Evaluation of blockbuster drugs under the rule-of-five. Archiv der Pharmazie. 2010;65(2):148–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walters W.P. Going further than Lipinski’s rule in drug design. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery. 2012;7(2):99–107. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2012.648612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nendza M., Müller M. Screening for low aquatic bioaccumulation (1): Lipinski’s “rule of 5” and molecular size. SAR and QSAR in Environmental Research. 2010;21(5-6):495–512. doi: 10.1080/1062936X.2010.502295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Balouiri M., Sadiki M., Ibnsouda S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: a review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2016;6(2):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rahman M., Hasan M.F., Das R. The determination of antibacterial and antifungal activities of Polygonum hydropiper (L.) root extract. Advances in Biological Research. 2009;3(2):53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhalodia N.R., Nariya P.B., Shukla V.J. Antibacterial and antifungal activity from flower extracts of Cassia fistula L.: an ethnomedicinal plant. International Journal of PharmTech Research. 2011;3(1):160–168. [Google Scholar]