Abstract

Binge drinking is a widespread alcohol consumption pattern commonly engaged by youth. Here, we present the first systematic review of emotional processes in relation to binge drinking. Capitalizing on a theoretical model describing three emotional processing steps (emotional appraisal/identification, emotional response, emotional regulation) and following PRISMA guidelines, we considered all identified human studies exploring emotional abilities among binge drinkers. A literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and PsychINFO, and a standardized methodological quality assessment was performed for each study. The main findings offered by the 43 studies included are, 1) regarding emotional appraisal/identification, binge drinking is related to heightened negative emotional states, including greater severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms, and have difficulties in recognizing emotional cues expressed by others; 2) regarding emotional response, binge drinkers exhibit diminished emotional response compared with non-binge drinkers; 3) regarding emotional regulation, no experimental data currently support impaired emotion regulation in binge drinking. Variability in the identification and measurement of binge drinking habits across studies limits conclusions. Nevertheless, current findings establish the relevance of emotional processes in binge drinking and set the stage for new research perspectives to identify the nature and extent of emotional impairments in the onset and maintenance of excessive alcohol use.

Keywords: emotional identification, emotional response, alcohol

1. Introduction

Binge drinking consists of drinking large quantities (more than 60 gr of pure ethanol on one occasion, leading to a blood alcohol concentration level of at least 0.08%) in a short time interval – usually less than two hours (Courtney & Polich, 2009; NIAAA1, 2004; WHO2, 2018). This drinking pattern is common to youth from adolescence to young adulthood in most Western countries (ESPAD3, 2016; SAMHSA4, 2016). Recent statistics show that almost 90% of young people (18 years old or older) have already drunk alcohol, and 30% engaged in binge drinking (NIAAA, 2018). Moreover, nearly 12% of youth before the legal age (12–20 years old, United States) and 40% of college students (18–22 years old) report binge drinking habits (NIAAA, 2018). As bingers drink heavily but irregularly, this habit is also characterized by withdrawal episodes. The repeated alternation between high intake and withdrawal, known to be particularly detrimental for brain functioning (Alaux-Cantin et al., 2013; Pascual, Blanco, Cauli, Miñarro, & Guerri, 2007), has guided some authors to propose that binge drinking might lead to cerebral impairments similar to those reported in severe Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) (e.g., Stephens & Duka, 2008). Comparable impairments between binge drinkers and patients with severe AUD have actually been identified by neuropsychological (see Carbia, López-Caneda, Corral, & Cadaveira, 2018a for a systematic review), neuroimaging, and electrophysiological (see Cservenka & Brumback, 2017; Maurage, Petit, & Campanella, 2013a for reviews) studies. Nevertheless, whereas emotion research constitutes a burgeoning field in severe AUD, explaining excessive drinking episodes and relapse risks (e.g., Bora & Zorlu, 2017; Le Berre, 2019), no paper has reviewed available data to determine the role of emotional processes in binge drinking. Emotional alterations play a role in excessive alcohol use but also in the development of comorbid affective disorders that influence control over drinking (Boden & Fergusson, 2011). Thus, identifying alterations in emotional control and related processes may enhance a fundamental understanding of youthful hazardous drinking. Moreover, the neurotoxic effects of alcohol on the developing brain together with emotional and stressful events occurring during adolescence may increase the propensity of emotional disturbances (Agoglia & Herman, 2018; Elsayed et al., 2018) and create a self-perpetuating disorder.

Dual-process Approach of Binge Drinking

Dominant neuroscientific models of addictive behaviors and models of binge drinking have focused on drug-driven emotions and inhibitory control (e.g., Goldstein & Volkow, 2011; Koob, 2015), without integrating emotional processes per se. Indeed, most studies capitalized on a dual-process view, proposing an interaction between two types of processes related to specific brain systems (e.g., Blanco-Ramos, Cadaveira, Folgueira-Ares, Corral, & Rodríguez Holguín, 2019; Carbia, Corral, Doallo, & Caamaño-Isorna, 2018b; Castellanos-Ryan, Rubia, & Conrod, 2011; Lannoy, Billieux, & Maurage, 2014; Oei & Morawska, 2004; Peeters et al., 2012). The first one, System A, is sustained by the (bottom-up) limbic brain network (Hampton, Adolphs, Tyszka, & O’Doherty, 2007) and involves processes such as automatic/motivational tendencies (e.g., positive bias towards alcohol; Carbia et al., 2018b; reward-seeking, expectancies towards alcohol; Castellanos-Ryan et al., 2011; Oei and Morawska, 2004). The second one, System B, is sustained by the (top-down) prefrontal brain network (Daw, Niv, & Dayan, 2005) and encompasses cognitive processes such as executive functions or more specifically the ability to control alcohol consumption (Lannoy, Maurage, D’Hondt, Billieux, & Dormal, 2018a; Oei & Morawska, 2004). In line with what has been found in severe AUD, results showed an imbalance between these systems in binge drinking: high alcohol bias/expectancies towards alcohol combined with poor executive control predicts binge drinking (Carbia et al., 2018b; Morawska & Oei, 2005; Peeters et al., 2012). Studies focusing on adolescence also speculated that the interaction between Systems A and B would be explained by a brain maturation imbalance: (a) limbic and paralimbic brain areas mature during early adolescence, following hormonal changes, and this modification results in increased reward sensitivity; (b) conversely, prefrontal and parietal cortices mature gradually during late adolescence, and this later maturity explains poor control abilities (Shulman, Harden, Chein, & Steinberg, 2015; Steinberg, 2007). The interaction between heightened reward sensitivity and poor control abilities might therefore lead to risk-taking behaviors in adolescence (Casey & Jones, 2010; Somerville, Hare, & Casey, 2011; Steinberg, 2007), including binge drinking (Noël, 2014; Peeters, Vollebergh, Wiers, & Field, 2014). These proposals, however, have been based primarily on studies exploring System A functioning through cue-reactivity, System B functioning through memory/executive function abilities, or both systems. To address the dearth of knowledge regarding the contribution of emotional processes, this review considers how emotional processing adds value to the current understanding of binge drinking.

1.1. The Role of Emotion

Emotion plays an essential role in the emergence and maintenance of psychopathological disorders. A dominant theoretical view for describing emotion depicts it as a multidimensional response comprising multiple components of emotional processing (Phillips, Drevets, Rauch, & Lane, 2003a). The constellation of components combines three successive steps, usually following a stimulus presentation: emotional appraisal and identification, emotional response, and emotional regulation (Phillips et al., 2003a). As this model identifies distinct emotional processes and has received strong support (e.g., Pessoa, 2017), we will use it as a theoretical framework for the present review. First, emotional appraisal and identification allow assessing an emotional stimulus or situation. Emotional stimuli may be internal (self-emotional states) or external (situation or other individuals’ emotional expressions). In human research, this process has been investigated by self-report questionnaires requiring one to identify internal states (for internal stimuli) or by paradigms requiring the identification of emotionally salient stimuli; e.g., facial emotional expressions, emotional scenes (for external stimuli). Specific brain regions are involved in this external identification, namely the amygdala, insula, ventral striatum, thalamus, and hypothalamus (Britton et al., 2006; Murphy, Nimmo-Smith, & Lawrence, 2003; Pessoa, 2017; Phillips et al., 2003a). Second, emotional response is a reaction to the emotional situation. The inference of the emotional experience leads to feelings and reactions. This response is often described by cognitive, physiological, and behavioral correlates (e.g., danger-related thoughts, accelerated heartbeats, increased sweat, behavioral approach/avoidance tendencies). In human research, this process has been investigated by paradigms inducing affective states (e.g., mood induction, fear conditioning). The brain regions associated with this process are the amygdala, ventral striatum, insula, and orbitofrontal cortex (Britton et al., 2006; Murphy et al., 2003; Phillips et al., 2003a). The final stage of emotional processing is the emotional regulation of affective states and action tendencies (e.g., voluntarily slowing breath, using relaxation or cognitive restructuring). This step is critical for personal and social adaptation, poor emotional regulation being considered a central transdiagnostic process explaining several psychopathological states (see Sloan et al., 2017 for a review). In human research, emotional regulation has been investigated by paradigms involving response to or control from responding to emotional stimuli. The specific neural correlates associated with this process are the anterior cingulate and dorsomedial prefrontal cortices (Esperidião-Antonio et al., 2017; Murphy et al., 2003; Phillips et al., 2003a; Stevens, 2011).

These emotional processing steps enable disentanglement of the complexity of emotions and allow the exploration of individual abilities to process and react to emotional stimuli. It is worth noting that these steps are frequently intertwined, but can also be reported independently (e.g., an emotional response may occur without a specific emotional stimulus presentation and evaluation). Critically, this model describes emotional processing as the successive steps occurring in a specific situation, but the processing of emotional signals may also lead to long-term emotional outcomes (e.g., depressive symptoms; Phillips, Drevets, Rauch, & Lane, 2003b). The relationship between alcohol and depression being crucial to better understand the onset and perpetuation of alcohol misuse (Boden & Fergusson, 2011), this paper will consider both short-term (e.g., self-reported emotional states at the time of the study) and long-term (e.g., persistent and significant depressive or anxious symptoms) perspectives.

In severe AUD, the role of emotional processing is critical and may explain the maintenance of substance abuse (Koob, 2015). Although patients can exhibit emotional deficits resulting from the alcohol’s effects on the brain (Bora & Zorlu, 2017), these emotional deficits can also be involved in relapse (Le Berre, 2019). Patients with severe AUD are impaired for the whole emotional processing stream, with deficits in emotional identification and regulation particularly salient (Le Berre, 2019). In binge drinking, the study of emotional processes only emerged recently. It has been proposed that the repeated alternations between high alcohol consumption and abstinence led to deleterious brain effects in binge drinking, especially in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, which might produce similar emotional impairments than those observed in severe AUD (Stephens & Duka, 2008). The aim of this review is to highlight how emotion research may bring insight into understanding the antecedents and consequences of binge drinking. We aim to explore which emotional processing steps are altered in binge drinking and how emotional impairments may be related to alcohol-related outcomes in a non-clinical population. For this purpose, we adopted a comprehensive and systematic approach to review emotion studies in binge drinking for the first time. We expect that emotional difficulties will be reported in binge drinking, particularly for emotional identification and response, as these stages appear particularly related to the effects of alcohol (Bora & Zorlu, 2017; Stephens & Duka, 2008).

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria and Articles Selection

The systematic research has been conducted according to the model of emotional processing previously described (Phillips et al., 2003a; 2003b). The reliability of this framework is supported in various studies (e.g., Caparelli et al., 2017; Rutter et al., 2019) and offers a theoretically driven research including distinct emotional processes. As this research field is nascent, lenient inclusion criteria were used to offer a broad representation of the field. To determine inclusion criteria, we used a modified PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study design/setting) procedure for observational studies (Liberati et al., 2009): (1) the Population referred to human participants (adolescents and adults, identified age range: 13–74 years old) with current binge drinking (as a pattern of alcohol consumption) or having presented at least one binge drinking episode. Studies referring to other patterns of alcohol use (e.g., severe AUD, maternal binge drinking) that may bias the current results were excluded. We also excluded animal studies. In order to offer a comprehensive view of the relationship between binge drinking and emotional processing, no exclusion criterion was related to personal, demographic, and socio-economic characteristics. Regarding psychopathological conditions, we included studies assessing depression and anxiety, as these psychopathological symptoms are closely related to impaired affective processing and thus of critical importance when considering the links between emotional variables and binge drinking. The presence of other psychopathological disorders not related to emotional processes (e.g., Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder) constituted an exclusion criterion as they may bias the interpretation of emotional difficulties (e.g., the difficulties observed may not be specifically related to binge drinking but rather, at least partly, to the comorbid pathological condition, which is not directly related to emotional processing and, therefore, out of the scope of the present review); (2) regarding Intervention, we focused on alcohol drinking and considered both the immediate (i.e., emotional processing after drinking alcohol; acute consumption) and long-term alcohol influence (i.e., stable emotional processing among binge drinkers, outside the intoxication episodes). As the definition of binge drinking varies widely across studies, we included all studies referring to the concept of binge drinking, recognizing that the specificity of alcohol use criteria would be evaluated in the quality assessment; (3) as Comparator, we considered two types of studies: those presenting experimental comparisons (between binge drinking and control groups or between emotional and control conditions) and those evaluating the relationship between binge drinking and emotional processing (without group comparison), controlling for personal, demographic, and psychopathological variables when statistically appropriate; (4) the Outcome focused on emotion. Accordingly, research using self-report measures, behavioral tasks, electrophysiological, or neuroimaging data were included if participants were required to process emotional information or if emotional measures were taken; (5) the Study design included correlational or experimental studies but excluded research focused on the evaluation of clinical interventions as well as single-case or case series studies or publications without experimental data (e.g., comments, reviews).

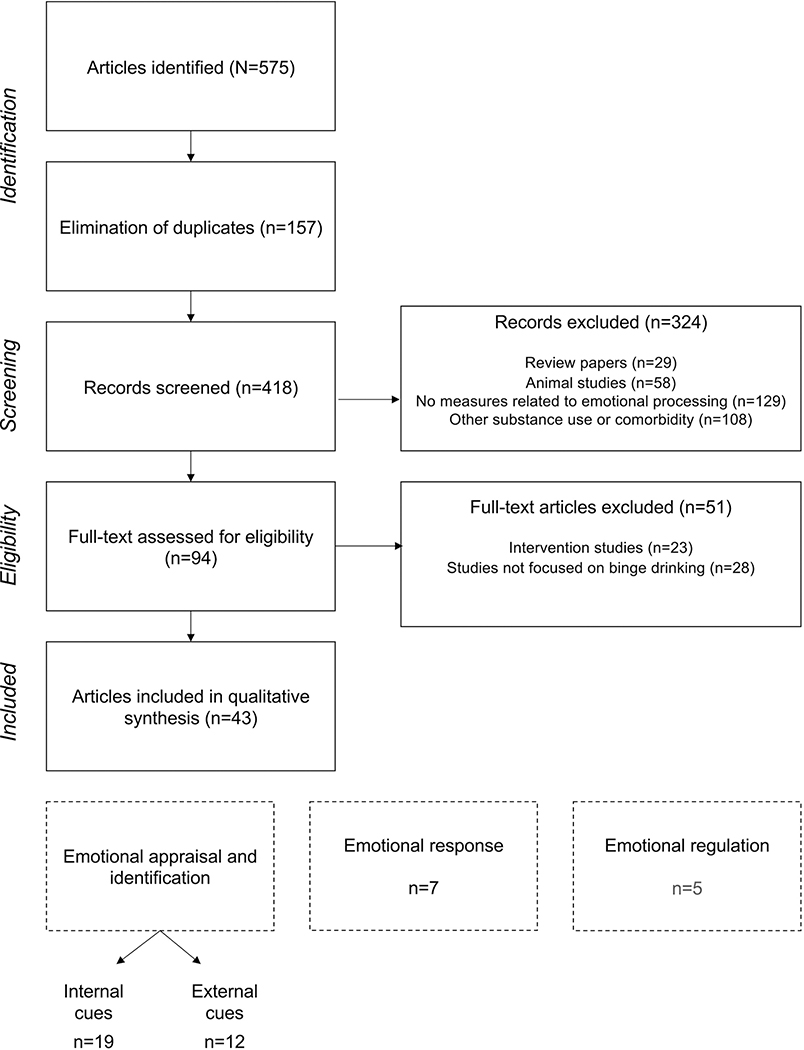

The guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) were followed (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009), as reported in the PRISMA checklist (see supplementary material). Inclusion criteria included peerreviewed articles published in English between January 1st, 2000 and June 1st, 2020. The systematic research was conducted in three databases (Pubmed, Scopus, PsychINFO). Keywords were determined following the theoretical proposal of Phillips and colleagues (2003a) for emotion (emotional appraisal OR emotional identification OR emotional response OR emotional regulation OR emotion OR emotions) and related to binge drinking (binge drinking OR heavy drinking OR social drinking OR college drinking). The initial search produced 575 papers, 43 of which met inclusion criteria for this review (see Figure 1 for a flowchart of article selection). As an example, the search for emotional response AND binge drinking in PubMed led to 72 results, 18 were removed because they were already found in other research (i.e., emotional appraisal, emotional identification) and 54 abstracts were screened. Articles were excluded when they did not focus on human studies (n=11), emotional processing (n=16), or binge drinking (n=10). We read 17 full-texts and excluded six other articles (intervention studies, no binge drinking measure). Then, four articles were included, related to internal emotional identification (i.e., Bekman, Winward, Lau, Wagner, & Brown, 2013; Pape & Norström, 2016; Scaife & Duka, 2009, Strine et al., 2008). The final research led to the identification of seven articles, included for the evaluation of emotional response. This procedure was applied for all searches. The first author performed the search in the databases and the first and last authors (SL and PM) conducted the articles’ selection based on exported PDF files.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of articles selection

Figure 1 illustrates the different steps of article selection and inclusion through the PRISMA guidelines (identification, screening, eligibility, inclusion), and the number of articles kept and excluded at each selection step. The procedure leads to the inclusion of 43 articles, 19 related to internal emotional identification, 12 related to external emotional identification, 7 related to emotional response, among which one also informs about emotional regulation, and 5 more related to emotional regulation.

2.3. Methodological Quality Assessment

The existing literature describes many ways to assess the quality of research studies without a specified standard (Zeng et al., 2015). Indeed, such assessments may appear subjective and have to be adapted according to the specific aims of each review. Consequently, for the present review, identified articles were assessed based on an adapted version of the AXIS criteria (Downes, Brennan, Williams, & Dean, 2016). This tool was developed to be adapted across all scientific disciplines, and its reliability was ensured by a Delphi panel (validation of 18 experts) (Downes et al., 2016). Its non-specificity affords a simple and clear way for a critical appraisal of the literature, which matched our aim to include studies using a variety of approaches (e.g., neuroscience, psychology) to assess emotional processing.

The final criteria appear in Table 1, with the detailed evaluation of each study. In summary, six items were deleted or modified from the original scale because they were not directly relevant: items 8 and 9 were combined in a unique item (item 13 in the adapted scale, referring to manipulation of the dependent variable and its appropriateness), evaluation of sample size was added in item 3 (to determine what a sufficient sample size was, we referred to previous studies and defined a minimum of 25 participants for group studies; Carbia et al., 2018a, and 52 participants per predictors for correlational studies; Maxwell, 2000), and items 13, 15, and 19 were deleted as they referred to non-response bias, internal consistency (already assessed in other items), and conflicts of interest, respectively. Several adaptations were also conducted regarding selection criteria and representativeness of the population to meet the specific needs of the present paper (e.g., evaluation of timeframe, intensity, and frequency of binge drinking). To increase the procedure reliability, this quality assessment was performed by two independent judges (authors SL and PM). The total agreement between the assessors was 87.9% (= 605/688), which can be evaluated as very strong (McHugh, 2012). Assessment discrepancies were related to two items (6 and 10). Thus, the minimum quantity of alcohol in a binge drinking episode (i.e., the consumption of at least 60 gr of pure ethanol on one occasion, 56 gr was considered if authors used distinct categorization for girls; binge drinking score) and the reliable ways to determine statistical significance to reach a consensus (e.g., p-values, confidence intervals) were discussed. A score (i.e., percentage of “Yes” answers) was computed to provide an overview of the quality associated with each study (i.e., poor quality for scores below 50%, fair quality for scores between 50 and 69%, good quality for scores between 70% and 79%, strong quality for scores of 80% and beyond; Black et al., 2017; Maurage, Masson, Bollen, & D’Hondt, 2020).

Table 1.

Studies scoring using the adapted quality assessment AXIS (Downes et al., 2016).

| Authors | Date | AXIS Items |

% score |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3a/b | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Balodis et al. | 2011 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 64.71 |

| Bekman et al. | 2013 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 82.35 |

| Carbia et al. | 2020 | Y | Y | Y/N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 76.47 |

| Chen & Feeley | 2015 | Y | N | Y/N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | 41.18 |

| Cohen-Gilbert et al. | 2017 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 76.47 |

| Connell et al. | 2015 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 64.71 |

| Ehlers et al. | 2007 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 70.59 |

| Ehret et al. | 2013 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 64.71 |

| Ewing et al. | 2010 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 76.47 |

| Gowin et al. | 2020 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 88.24 |

| Hartley et al. | 2004 | Y | Y | N/Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 88.24 |

| Haynes et al. | 2005 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 88.24 |

| Hefner et al. | 2013 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 58.82 |

| Herman et al. | 2018 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 70.59 |

| Howland et al. | 2010 | Y | Y | Y/Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 82.35 |

| Huang et al. | 2018 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | 76.47 |

| Khan et al. | 2018 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 70.59 |

| Laghi et al. | 2018 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 70.59 |

| Lannoy et al. | 2017 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 82.35 |

| Lannoy et al. | 2018 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 82.35 |

| Lannoy et al. | 2018 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 82.35 |

| Lannoy et al. | 2019 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 88.24 |

| Leganes-Fonteneau et al. | 2020 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 70.59 |

| Lindgren et al. | 2018 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 64.71 |

| Loeber & Duka | 2009 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 58.82 |

| Maurage et al. | 2009 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 82.35 |

| Maurage et al. | 2013 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 82.35 |

| Mngoma et al. | 2020 | Y | N | Y/N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 47.06 |

| Mushquash et al. | 2013 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 64.71 |

| Nourse et al. | 2017 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 64.71 |

| Pape & Norström | 2016 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 94.12 |

| Pedersen | 2013 | Y | N | Y/N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | 47.06 |

| Poncin et al. | 2017 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 58.82 |

| Rose & Grunsell | 2008 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | 58.82 |

| Ruiz et al. | 2020 | Y | Y | Y/N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 76.47 |

| Scaife & Duka | 2009 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 82.35 |

| Stephens et al. | 2005 | Y | Y | N/N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 76.47 |

| Stickley et al. | 2014 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 64.71 |

| Strine et al. | 2008 | Y | Y | Y/N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 76.47 |

| Townshend & Duka | 2005 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 88.24 |

| Trojanowski et al. | 2019 | Y | Y | Y/N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 82.24 |

| Venerable & Fairbairn | 2020 | Y | Y | Y/Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 76.47 |

| Wichaidit et al. | 2020 | Y | Y | Y/N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 64.71 |

Legend: N = No; Y = Yes

Note: Question related to each item:

Introduction

(1) Were the aims/objectives of the study clear?

Methods

(2) Was the study design appropriate for the stated aim(s)?

(3) Was the sample size (a) sufficient (i.e., at least 25 subjects per group or 52 per predictor) and (b) justified (i.e., power analysis, reference to samples or effect sizes reported in earlier studies)?

(4) Was the target/reference population clearly defined (Is it clear who the research was about?)?

(5) Were measures undertaken to address and categorize non-responders?

(6) Were the selection criteria clearly defined and selective enough (e.g., alcohol intensity) to focus on binge drinkers?

(7) Was the timeframe of binge drinking habits enough (i.e., 6 months), so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between binge drinking and emotional processes?

(8) Were key potential confounding variables considered (e.g., included in pre-selection criteria or adjusted statistically)?

(9) Were key potential confounding and outcome variables measured appropriately?

(10) Is it clear what was used to determine statistical significance and/or precision estimates (p-values, CIs)?

(11) Were the methods (including statistical methods) sufficiently described to enable them to be repeated/reproduced?

Results

(12) Were the basic measures (i.e. demographics) adequately described?

(13) Were the dependent variables (i.e. emotional processes) manipulated, and was this manipulation adequately described?

Discussion

(14) Were the authors’ discussions and conclusions justified by the results?

(15) Were the limitations of the study discussed?

Other

(16) Was ethical approval or consent of participants attained?

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Studies

For each study, data were extracted systematically using the PICOS framework. All details regarding the sample, inclusion/exclusion criteria, or emotional processes and measures are reported in Tables 2–4. The Results section describes the key conclusions related to each research study and is divided into three sub-sections, organized according to the theoretical model of emotional processing (Phillips et al., 2003a): emotional appraisal and identification (subdivided in self/internal emotional identification and other/external emotional identification), emotional response, and emotional regulation.

Table 2.

Description and main results of studies evaluating emotional appraisal and identification in binge drinking.

| Authors (year) | Participants | Intervention | Comparator | Experimental design | Outcomes | Scoring | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (n) | Age | Gender ratio (% of males) | Inclusion criteria | Binge drinking criteria | Control group/variable | Processes measured | Task/scale | Stimuli | Main results | Limits | ||

| Emotional identification of internal cues | ||||||||||||

| Bekman et al. (2013) | 39 BD | Range 16–18 Mean 17.74 |

51% | No recent substance consumption No psychiatric or neurological disorders |

Drinking alcohol on more than 100 occasions at lifetime. At least 3 binge drinking episodes (≥ 70 alcohol gr for boys and ≥ 56 gr for girls on one occasion) during the past month At least 1 withdrawal symptom following a recent drinking episode |

26 non-BD (no history of binge drinking or alcohol use problems) | Anxiety and depression Mood |

6-week research following abstinence: two assessments (start and end) and daily follow-up (3–6 times/day) The Hamilton Rating Scales for Anxiety and Depression State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Self-reported negative affects (down, angry, and stressed) |

N/A | Negative affect at early stage of abstinence: BD > non-BD Depression, anxiety: BD > non-BD Correlations between negative affect and maximum number of drinks consumed on one occasion and total number of drinks |

No information about affective states prior the onset of alcohol use | 82.35 |

| Chen & Feeley (2015) | 179 college students | Range 18–29 Mean 19.76 |

46.9% | N/A | Number of binge drinking episodes in the past 2-week (≥ 70 alcohol gr for boys and ≥ 56 for girls in 2 hours) | Analyses were controlled for age, gender, ethnicity, and health status | Stress Loneliness |

2-week research Perceived Stress Scale UCLA Loneliness Scale |

N/A | Students with higher stress depicted increased binge drinking 2 weeks later No associations were found with loneliness |

Convenience sample | 41.18 |

| Ewing et al. (2010) | 45 college students | Range 21–33 Mean 22.8 |

44.44% | No MRI contraindication, personal or family history of psychopathological disorder, current medical condition, mental retardation, left handedness, or current substance use No alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine use prior scanning |

At least 42 alcohol gr (men) or 28 (women) per drinking occasion, 2–5 times per week, for 4 weeks Number of binge drinking episodes (at least 70 gr) in the past month |

N/A | Depressive symptoms Anxiety symptoms |

AUDIT Beck Depression Inventory Beck Anxiety Inventory fMRI: taste-cue paradigm (alcohol and non-alcohol appetitive cues) |

N/A | Depression was positively associated with brain activations (insula, cingulate, ventral tegmentum, striatum, and thalamus) while viewing alcohol cues Anxiety was positively associated with brain activations (striatum, thalamus, insula, and inferior frontal, mid-frontal, and cingulate gyri) while viewing alcohol cues |

No control group | 76.47 |

| Hartley et al. (2004) | 14 BD | Range 18–23 Mean 21.13 |

64.3% | N/A | ≥ 80 alcohol gr on one occasion Binge drinking score ≥ 24 |

13 teetotalers | Trait anxiety and depression Mood |

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Visual analogue rating scales (alertness, well-being, anxiety) |

N/A | Trait anxiety and depression: BD < teetotalers NS for mood rating |

Comparison with a group of non-drinkers (i.e., it assesses the effect of alcohol consumption but not a specific effect of binge drinking) | 88.24 |

| Haynes et al. (2005) | 8,580 adults at baseline | 18–74 | N/A | Absence of mental disorder at baseline | ≥ 48 alcohol gr on one occasion at least once a month | Analyses were adjusted for age, gender, socio-demographic and -economic variables, other substance use and mental health | Depression | 18-month study Clinical Interview Schedule at baseline (n=2,413 who completed the follow-up have no mental disorder) AUDIT Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire |

N/A | Hazardous drinking, binge drinking, and severe alcohol use disorders were not related to anxiety or depression at follow-up Sub-threshold of anxiety and depression at baseline was related to the onset of severe alcohol use disorders (weak evidence) |

No information about the evaluation of depression and anxiety during the 18 months (e.g., recovery) | 88.24 |

| Howland et al. (2010) | 193 college students | Range 21–24 Mean 21.47 |

No alcohol problems or other substance use, no medical condition No night shifts work, no regnancy, no travel across two or more time zones in the prior month |

At least one binge drinking episode (≥ 70 alcohol gr for boys or ≥ 56 for girls) in the past month Alcohol administration: 1.068 g/kg for boys and 0.915 g/kg for girls with cans of beer in one-hour interval. Non-alcoholic beer as placebo condition. |

Analyses were controlled for gender and session Alcohol administration versus placebo |

Mood | 2-week research (alcohol versus placebo) and assessment following beverage administration (morning and afternoon) Profile of Mood States |

N/A | Mood was affected the morning after alcohol consumption (BAC of 12%) | Not reported | 82.35 | |

| Mngoma et al. (2020) | 355 youth | Range 14–24 Mean 18.6 |

100% | N/A | No specific binge drinking criteria | N/A | Anxiety Depression |

Brief Symptom Inventory Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale Social Provisions Scale Substance use |

N/A | Suicidal thoughts were associated with depression, anxiety, worthlessness, and binge drinking | No inclusion of women | 47.06 |

| Mushquash et al. (2013) | 191 women | Mean 19.9 | N/A | N/A | Dichotomic alcohol measure: 0: no more than 56 gr in 2 hours 1: more than 56 gr in 2 hours at least once in the past week |

N/A Use of structural equation modeling |

Depression Mood |

4-week research Depression Adjective Checklist Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale Profile of Mood States |

N/A | Depressive symptoms predicted binge drinking over one week but binge drinking did not predict depression. | No inclusion of men | 64.71 |

| Nourse et al. (2017) | 201 college students | Mean 21.1 | 25.4% | N/A | AUDIT score ≥ 7 | N/A | Anxiety Depression |

Generalized Anxiety Questionnaire Patient Health Questionnaire AUDIT |

N/A | No association between hazardous drinking and depression or anxiety | No inclusion of men Small convenience sample |

64.71 |

| Pape & Norström (2016) | 2,171 youth people | Range 13–17 Time 1 Mean 14.9 |

43% | N/A | Frequency of alcohol use and intoxication feelings in the past 12 months | Separate analyses according to age (to consider developmental trajectories) and gender | Anxiety Depression Loneliness (as a control measure at the longitudinal level) |

13-year research, 4 assessment times The Hopkins Symptom Check List The Depressive Mood Inventory UCLA Loneliness Scale |

N/A | Emotional distress was not associated with binge drinking in early adolescence From adolescence to adulthood (mean age: 16.4 yo to 21.8 yo) and in late adulthood (mean age: from 21.8 yo to 28.3 yo), depression, but not anxiety, was positively associated with binge drinking |

Subjectivity related to the binge drinking measure | 94.12 |

| Pedersen (2013) | 248 college students | Range 18–29 Mean 20.83 |

37.09% | N/A | Number of binge drinking episodes (≥ 70 alcohol gr for boys or ≥ 56 for girls) in the past month | Separate analyses for men and women. Analyses controlled for class level and employment status | Depressive mood Stress |

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) School stress scale |

N/A | In men, binge drinking was positively related to depression In women, the relation between binge drinking and depression was explained by class level (first university year), employment status (higher number of work hours) and school-related stress |

Single-item measure of depression | 47.01 |

| Rose & Grunsell (2008) | 10 BD | Range 18–25 Mean 21.5 |

50% | No psychiatric or substance use disorder, no current medication No alcohol drinking, caffeine, or fat meal before the experiment |

≥ 80 alcohol gr per week Binge drinking score ≥ 24 Alcohol administration: 0.6 g/kg for boys and 0.5 g/kg for girls with lemonade in a 500 ml solution drank in a 30-minute period. In the control condition, 500 ml of lemonade with drops of ethanol (≤ 5 ml) |

10 non-BD (binge drinking score ≤ 16) Alcohol administration versus placebo |

Mood | Visual Analog Scale (alert, content, relaxed, stimulated, lightheaded, and irritable), completed (1) before alcohol drinking and (2) 30 minutes after drinking alcohol | N/A | Ratings of “stimulated” decreased between baseline and post-preload: (1) placebo condition, BD < non-BD (2) alcohol condition, BD > non-BD Ratings of “lightheaded” following alcohol preload, BD < non-BD |

Not reported | 58.82 |

| Ruiz et al. (2020) | 1505 participants | Range 18–30 Mean 23.25 |

25% | N/A | Number of binge drinking episodes (≥ 70 alcohol gr for boys or ≥ 56 for girls on one occasion) in the last 12 months Late drinkers (first alcohol use after 15 yo) and early drinkers (first alcohol use before 14 yo) |

Analyses were controlled for the total volume of alcohol consumed and sex | Emotional distress | AUDIT Alcohol consequences questionnaire Kessler Scale of psychological distress (anxiety, depression, and non-specific distress) Doherty Scale of Emotional Contagion |

N/A | Psychological distress: Early drinkers > Late drinkers Significant relationship between psychological distress and negative consequences of alcohol Psychological distress was not associated with binge drinking but with negative consequences of alcohol |

Not reported | 76.47 |

| Scaife & Duka (2009) | 30 BD | Range 18–29 Mean 20.6 |

60% | No use of illicit drug or medication 1 week before the experiment, no alcohol drinking 12 hours before the experiment | Binge drinking score > 31 (median split) | 30 non-BD (binge drinking score < 31) | Mood | Profile of Mood States | N/A | No significant difference between BD and controls, only a gender effect showed higher arousal in female | Not reported | 82.35 |

| Stickley et al. (2014) | 4,045 adolescents | Range 13–15 | 47.4% | N/A | Drinking more than 70 alcohol gr on one occasion at least once in the past month | Analyses controlled for age, parental education, family structure, and depressive symptoms. | Loneliness | Adapted Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale | N/A | Loneliness was associated with binge drinking in the last month among adolescents in the US | Single-item measure of loneliness | 64.71 |

| Strine et al. (2008) | 217,379 adults | 18 or older | N/A | N/A | ≥ 70 alcohol gr for boys and ≥ 56 for girls on one occasion in the past month Heavy drinking: > 28 gr per day for boys and > 14 for girls |

Analyses were adjusted by sex, age, socio-demographic and -economic status | Anxiety and depression | Patient Health Questionnaire Evaluation of smoking habits, height, weight, physical activity, and alcohol consumption |

N/A | Adults who presented current depression or had a lifetime history of depression or anxiety exhibited increased smoking, obesity, physical inactivity, binge, and heavy drinking | No information on the causality link between anxiety/ depression and alcohol use | 76.47 |

| Townshend & Duka (2005) | 38 BD | Range 18–30 Mean 20.9 |

60.5% | No psychopathological disorder, neurological disorder, or substance use disorder No use of drug, sleeping tablet, hay fever and alcohol prior the experiment |

≥ 48 alcohol gr per week Binge drinking score ≥ 24 |

34 non-BD (binge drinking score ≤ 16) | Mood | Profile of Mood States | N/A | BD had less positive mood | Self-reported alcohol use | 88.24 |

| Venerable & Fairbairn (2020) | 60 BD | Range 21–28 Mean 22.5 |

50% | No medical contraindication for alcohol drinking No severe alcohol use disorders, extreme body mass index, and no pregnant women |

Drinking at least 2 times/ week, 56 alcohol gr per occasion Number of binge drinking episodes (≥ 70 alcohol gr for boys or ≥ 56 for girls on one occasion) in the past 30 days Alcohol administration 0.82 g/kg for boys and 0.74 g/kg for girls (mix of cranberry and vodka) served in three equal parts at 0, 12, and 24 min. In the control condition, isovolumic amount of cranberry juice |

Comparison between alcohol and placebo sessions Analyses exploring the effects of alcohol on mood were controlled for predrink mood and lagged mood |

Mood | 7-day study, 18-month follow-up Self-report mood, anxiety, and alcohol-related stimulation and sedation Transdermal sensors (7 days) Mood scale: positive (upbeat, content, happy, euphoric, energized) and negative (nervous, sad, irritated, lonely, bored) mood after alcohol use Short Inventory of Problems |

N/A | When controlling for baseline drinking, greater negative mood reduction after alcohol drinking predicted drinking problems at follow-up Greater positive mood after alcohol drinking also predicted drinking problems and binge drinking at follow-up |

Less BD compared to non-BD answered at follow-up | 76.47 |

| Wichaidit et al. (2020) | 38,186 students | Age range 12–17 Mean 15.2 |

45.5% | N/A | At least one binge drinking episode (≥ 60 alcohol gr for boys and 50 for girls on one occasion) in the past month | Analyses were controlled for socio-demographic and -economic variable, substance use and psychopathology | Mood | Substance (tobacco, alcohol, illicit drug) and behaviors (gambling, sexual behaviors, gaming, and social media use) Patient Health Questionnaire |

N/A | Depressed mood was significantly associated with alcohol drinking in the past year, the past month, and with past-month binge drinking | No information on the causality | 64.71 |

| Emotional identification of external cues | ||||||||||||

| Carbia et al. (2020) | 180 college students at follow-up | Range 18–20 Mean 18.01 |

46.67% | No personal or family history of severe alcohol use disorder, illicit drug use, neurological or psychiatric disorders | Number of binge drinking episodes (≥ 60 alcohol gr for boys and ≥ 40 gr for girls) in the last 3 months | Analyses were controlled for cannabis use, tobacco use, and psychopathology | Emotional memory | 2-year research AUDIT Alcohol Timeline Followback Emotional Verbal Learning Test (assessed at follow-up) |

Positive, negative, and neutral words | Boys: no significant effect Girls: BD had an emotional memory bias for negative words, lower recall for positive and neutral words, increased false alarms for negative emotional distractors. |

No neuropsychological assessment at baseline | 76.47 |

| Ehlers et al. (2007) | 30 BD 59 BD and drug users |

Range 18–25 Mean 19.91 |

50% | No psychiatric disorder | At least one binge drinking episode (> 70 alcohol gr) during adolescence; with or without drug consumption | 36 non-BD and non-drug users | Emotional identification | Facial discrimination task (answer to happy or sad faces and do not answer to neutral) EEG recording: event-related potentials (P3a and P3b) |

Happy, neutral, and sad faces | Binge drinking + drug use history: decreased P3a latency during the view of all faces Binge drinking and binge drinking + drug use: decreased P3b amplitude during the view of happy faces |

Cross-sectional alcohol use data | 70.59 |

| Gowin et al. (2020) | 177 BD | Range 22–35 Mean 27.9 |

72.31% | No lifetime history of alcohol abuse or dependence | At least one binge drinking episode (≥ 70 alcohol g for boys or ≥ 56 for girls on one occasion) per week in the last year | 309 non-BD | Emotional identification | Penn Emotion Recognition Test (happy, sad, angry, scared or neutral emotional faces) fMRI measures: Emotional task (matching of faces with angry, fearful, or neutral emotional expressions) |

Emotional facial expressions of happiness, sadness, anger, and fear compared to neutral ones | Machine learning: Emotion processing did not perform better than chance The best model to identify BD compared to non-BD included social and language processing |

Heterogeneity in the BD sample | 88.24 |

| Huang et al. (2018) | 32 BD | Range 18–30 Mean 23.3 |

50% | No history of neurological or neuropsychiatrie disorder, visual or auditive problem, learning difficulty, left-handed participant No drug or medication use before the study |

At least 5 binge drinking episodes (≥ 84 alcohol gr for boys or ≥ 70 for girls within 2-hour) in the last 6 months | 32 non-BD (no more than one binge drinking episode in the last 6 months) | Emotional appraisal | Appraisal of emotional images (9-point Likert scale) EEG recording: event-related theta power at frontal, central, and parietal sides |

Emotional scenes: negative, positive, erotic, and neutral stimuli | No behavioral difference in the ratings of emotional images. Modulation of event-related theta power (early and later processing): BD < non-BD |

Not reported | 76.47 |

| Khan et al. (2018) | 147 college students | Range 18–23 Mean 19.92 |

/ | No psychiatric disorder (inclusion of moderate depression), illicit substance use, or significant cognitive deficit | At least one binge drinking episode (≥ 50 alcohol gr for boys or ≥ 40 for girls in two hours) in the past month | Analyses were controlled for gender and drinking quantity | Distress tolerance | The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV The Distress Tolerance Scale Timeline Follow back Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire Beck Depression Inventory |

Appraisal of distress tolerance predicted alcohol-related problems in BD, when controlling for drinking quantity and sex differences. The relationship between alcohol-related problems and distress tolerance, absorption, and regulation was mediated by drinking to cope. |

No information on the causality | 70.50 | |

| Lannoy et al. (2017) | 20 BD | Range 18–23 Mean 19.73 |

45% | No personal or family history of severe alcohol use disorder, psychological, neurological or medical disorders, medication or drug use, normal visual and auditory abilities | Binge drinking score ≥ 16 | 20 non-BD (binge drinking score ≤ 12) | Emotional crossmodal identification | Emotional crossmodal task (identification of emotional stimuli of anger and happiness based on facial and vocal processing) | Emotional facial expression of anger and happiness Emotional bursts of anger and happiness |

No significant group difference Non-BD were slower than BD for the recognition of emotional faces |

Subjective evaluation of alcohol use (drunkenness) | 82.35 |

| Lannoy et al. (2018c) | 17 BD | Range 18–29 Mean 20.52 |

58.8% | No personal or family history of severe alcohol use disorder, psychological, neurological or medical disorders, medication or drug use, normal visual and auditory abilities | Binge drinking score ≥ 16, ≥ 60 alcohol gr per occasion, ≥ 20 gr per hour, 2–4 times per week | 17 non-BD (binge drinking score between 1 and 12, ≤ 30 alcohol gr per occasion, ≤ 3 times per week) 19 teetotalers |

Emotional crossmodal identification | Emotional crossmodal task (identification of emotional stimuli of anger and happiness based on facial and vocal processing) EEG recording |

Emotional facial expression of anger and happiness Emotional bursts of anger and happiness |

No significant behavioral difference N100 latency, anger: BD > non-BD, teetotalers P3b amplitude, congruent happiness: BD > non-BD, teetotalers in Crossmodal integration for anger in incongruent trials Latency: BD > non-BD, teetotalers Amplitude: BD>non-BD, teetotalers |

Small sample size | 82.35 |

| Lannoy et al. (2018b) | 23 BD | Range 18–27 Mean 20.02 |

47.8% | No personal or family history of severe alcohol use disorder, psychological, neurological or medical disorder, medication or drug use, normal visual abilities | Binge drinking score ≥ 16 | 23 non-BD (binge drinking score ≤ 12) | Emotional recognition | Facial emotional recognition test (morphed stimuli) | Facial emotional expressions of anger, contempt, disgust, fear, happiness, and sadness | Overall emotion recognition: BD < non-BD No specific effects of emotion |

Small sample size | 82.35 |

| Lannoy et al. (2019) | 52 BD | Range 18–27 Mean 21.09 |

65.4% | No personal or family history of severe alcohol use disorder, or psychiatric disorder | At least one binge drinking episode (> 60 alcohol gr) per month Binge drinking score ≥ 16 |

42 non-BD (no binge drinking episode in the last year, binge drinking score ≤ 12) | Emotional recognition | Facial emotional recognition test (morphed stimuli) | Facial emotional expressions of anger, contempt, disgust, fear, happiness, and sadness | Recognition of fear and sadness: BD < non-BD These deficits concerned 21.15 and 15.38% of the sample, respectively |

Possible influence of impaired participants on the group results | 88.24 |

| Leganes-Fonteneau et al. (2020) | 48 participants | Students Mean 21.2 Youth Mean 15.4 |

50% | No psychological or neurological disorder, normal visual abilities | High and low BD: median split on the binge drinking score Students, median score = 15.8 Youth, median score = 8.5 |

Comparison between high and low BD | Emotional identification | Emotional identification (matching of emotional word with emotional face; congruent or incongruent) Emotional perception threshold |

Facial emotional expressions of fear, anger, happiness, surprise, sadness, and disgust | Emotion identification, fear: low BD > high BD Emotional perception Sadness: low BD < high BD Happiness: low BD < high BD |

Recruitment of two BD groups that did not have the same consumption patterns | 70.59 |

| Maurage et al. (2009) | 18 BD at time 2 | Mean 18.16 | 38.9% | No positive family history of severe alcohol use disorder, tobacco or drug use, psychiatric, medical or neurological problem, auditory impairment | Baseline: low alcohol use, no binge drinking episode Time 2: distinction between BD (> 200 alcohol gr per week) and controls |

18 non-BD (< 30 alcohol gr per week) | Emotional identification | 9-month, two assessments: Emotional valence detection task (auditory stimuli, positive or negative valence) EEG recording: event-related potentials (P1, N2, P3) |

The word “paper” pronounced with prosody of anger and happiness | After 9 months, P1, N2, P3 latencies: BD > controls | No comparison between emotional cognitive event-related potentials | 82.35 |

| Maurage et al. (2013) | 12 BD | Range 19–32 Mean 23.8 |

58.3% | No positive personal or family history of severe alcohol use disorder, medical, psychiatric, or neurological problem, drug or tobacco use, auditory impairment, left-handedness participant | Consumption of more than 50 alcohol gr per occasion, at least 3 times a week; with consumption speed 20 gr per hour | 12 non-BD (< 20 alcohol gr per occasion, < 1 per week, < 10 gr per hour) | Emotional identification | Two-alternative forced choice task (morphed stimuli: fear – anger continuum) fMRI recording, whole brain |

Auditory stimuli expressing negative affective bursts related to fear and anger | Behavioral categorization: BD < non-BD Bilateral superior temporal gyrus: BD < non-BD Right middle frontal gyrus: BD > non-BD |

Small sample size | 82.35 |

Note. All alcohol units have been converted in grams of pure ethanol, according to the number of grams per unit in each country. BD = binge drinkers; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel of mental disorders; fMRI = functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging; EEG = electroencephalogram; yo = years old.

Table 4.

Description and main results of studies evaluating emotional regulation in binge drinking.

| Authors (year) | Participants | Intervention | Comparator | Experimental design | Outcomes | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (n) | Age | Gender ratio (% of males) | Inclusion criteria | Binge drinking criteria | Control group/variable | Processes measured | Task/scale | Stimuli | Main results | Limits | ||

| Cohen-Gilbert et al. (2017) | 23 college students | Range 18–20 Mean 18.80 |

Not reported | No MRI contraindication, neurological disorder, and use of illicit drugs. Low use of marijuana and tobacco No alcohol use before the experiment |

The number of binge drinking episodes (≥ 70 alcohol gr for boys or ≥ 56 for girls in one occasion) in the three-past month | Continuous view of binge drinking (0 – 19 BD episodes in the past three months) Contrast between emotional images (positive and negative) and neutral ones |

Impact of emotional scenes on the ability to inhibit an automatic response | Structured Clinical Interview Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms Go/No-Go task (letters as target stimuli; emotional images as preliminary background) fMRI recording |

Positive, negative, and neutral images from the IAPS | Negative emotional background: higher binge drinking episodes related to decreased activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex. Positive emotional background: non-significant results |

Small sample size | 76.47 |

| Ehret et al. (2013) | 1,084 college students | Mean age of 20.1 | 37% | N/A | At least one binge drinking episode (≥ 70 alcohol gr for boys or ≥ 56 for girls) in the last month | Analyses were adjusted for gender, membership affiliation in a fraternity or sorority, and typical weekly drinking | Emotional regulation | Daily Drinking Questionnaire The Rutgers Alcohol Problems Protective Behavioral Strategies Drinking Refusal Self-Efficacy (social pressure, emotional relief, opportunistic) Drinking Motives (enhancement, social, coping, conformity) |

N/A | Greater binge drinking in participants with lower protective behavioral strategies, poor drinking refusal self-efficacy for social pressure or emotional regulation Participants with high drinking refusal self-efficacy in social and emotional contexts: protective behavioral strategies were not related to alcohol consequences |

No information on the causality | 64.71 |

| Herman et al. (2018) | 30 college students | Range 18–37 Mean 23.40 |

30% | No MRI contradiction, mental or neurological disorder, no significant impairment of vision | Binge drinking score as a continuous variable | Continuous view of binge drinking Control by comparing fearful expressions to neutral ones |

Inhibition of fear (facial expressions) Impact of fearful emotional expressions on decision-making abilities (delay discounting) |

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Alcohol Use Questionnaire Affective Stop Signal Task (fearful and neutral facial expressions as target stimuli) Affective Delay Discounting Task (fearful and neutral facial before target trials) fMRI recording |

Emotional facial expressions of fear and neutral facial expressions | Successful inhibition of fear: higher binge drinking scores related to decreased activation in frontal and parietal brain areas Delayed reward after the fearful presentation: higher binge drinking scores related to decreased frontopolar activation |

No evaluation of socio-emotional functioning | 70.59 |

| Laghi et al. (2018) | 1,004 high-school students | Range 16–21 Mean 17.90 |

39.34% | N/A | At least one binge drinking episode (≥ 50 alcohol gr for boys or ≥ 40 for girls on one occasion) in the past two weeks | Comparison of three groups: 227 BD, 89 binge eaters, 37 participants presenting both binge behaviors | Emotion regulation | The binge eating scale Drinking quantity and frequency The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (expression suppression and cognitive reappraisal) |

N/A | Cognitive reappraisal: no group difference Expression suppression: BD < binge eaters and participants with both binge behaviors |

No consideration of confounding variables (e.g., negative emotions) | 70.59 |

| Trojanowski et al. (2019) | 776 college students | Range 17–22 Mean 18.79 |

20.10% | N/A | At least one binge drinking episode (≥ 70 alcohol gr for boys or ≥ 56 for girls on one occasion) in the past month | Mixture modeling was used to create four groups: BD, binge eaters, both bingers, and low bingers | Emotion regulation | Eating Disorder Examination Drinking Timeline Follow-back Drinking Motives and Eating Motives Questionnaire Thinness and Restricting Expectancies Inventory UPPS-P (negative and positive urgency, lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, sensation seeking) Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Beck Depression Inventory AUDIT Quality of Life Inventory |

N/A | Depression, eating disorders, impulsivity, emotion regulation, quality of life: Low binge < binge eaters and both bingers Social and enhancement motives: BD > low binge |

No information on the causality | 82.24 |

Note. All alcohol units have been converted in grams of pure ethanol, according to the number of grams per unit in each country. BD = binge drinkers; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; fMRI = functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

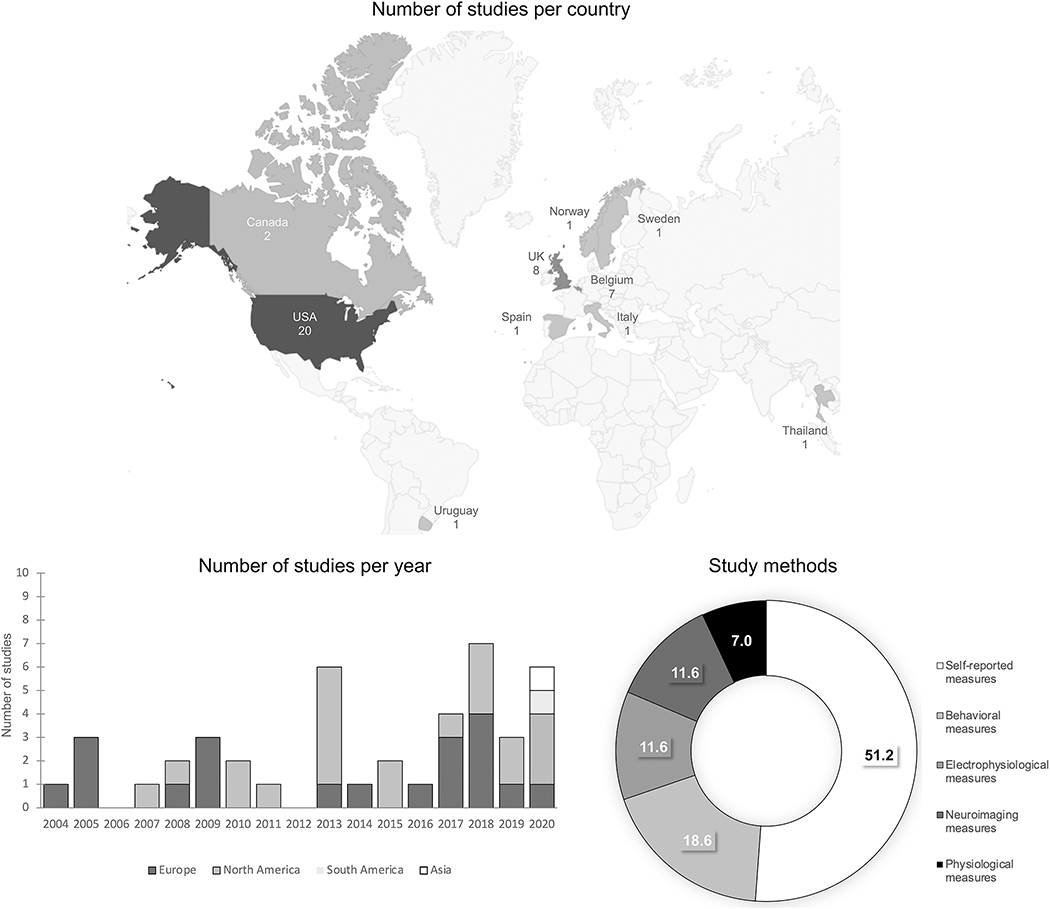

Study characteristics are illustrated in Figure 2. Regarding the geographical distribution (i.e., affiliation of the first author), the papers selected were mainly from North America (the United States of America and Canada) and Europe (the United Kingdom, Belgium, Sweden, Spain, and Italy), one from Uruguay, and one from Thailand. The yearly number of publications increased after 2012 and most studies were cross-sectional (81.4%). Among longitudinal studies (18.6%), seven were related to the evaluation of internal emotional states and its association with binge drinking and one with external emotional identification. Self-reported measures were mainly used to assess internal emotional identification and emotional regulation, whereas studies assessing external emotional appraisal/identification and emotional response used behavioral tasks or a combination of behavioral and neuroimaging/(electro)physiological measures. Only six studies (13.9%) focused on the effects of acute alcohol intake at binge-drinking level or among binge drinkers for the evaluation of emotional experience and emotional response. Finally, in 16 of the studies included (37.2%), participants had to process emotional stimuli (emotional scenes, emotional facial expressions, emotional words, or emotional voices).

Figure 2.

Description of the studies

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the studies included in this systematic review: the number of studies per country, the number of studies per year (studies conducted in Europe in dark grey, studies conducted in North America in light grey, studies conducted in South America in middle grey, and studies conducted in Asia in white), and the study methods (from white to black: 51.2% of studies used self-reported measures, 18.6% behavioral measures, 11.6% electrophysiological measures, 11.6% neuroimaging measures, and 7% physiological measures).

3.1. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the 43 studies (Table 1) was globally estimated as good according to the applied criteria (i.e., only three studies had a score below 50%). All studies had clear research objectives and the majority took the influence of confounding factors into account (e.g., depression, anxiety, drug use) (65.1%). The selected studies covered various designs and methodologies, but the vast majority proposed clear study aims and a justified experimental protocol. Nevertheless, most studies did not justify their sample size based on a priori power computation or previous experiments. Studies comparing groups with experimental measures also had small sample sizes (i.e., 60% had fewer than 25 participants per groups) with often unbalanced gender ratio (e.g., some studies focusing only on women). Moreover, we found a poor evaluation of binge drinking habits in 58.1% of the papers, few studies combining sufficient quantity (i.e., at least 56/60 gr) and timeframe (i.e., at least six months) measures to evaluate habit validly.

3.2. Emotional Processing in Binge Drinking

3.2.1. Emotional Appraisal and Identification (Table 2)

Emotional identification of internal cues.

This section comprises 19 studies that evaluated the identification of internal emotions. This subsection has been divided into two categories: 1) the current emotional states (i.e., those felt during the evaluation like stress or short-term negative/positive affect); 2) the longer-term and prolonged emotional states or mood disorders, like depression and anxiety.

First, the evaluation of current emotional states showed that binge drinking is differentially associated with loneliness, stress, and short-term affect according to age. In adolescents (13–15 years old), loneliness was related to past 30-day binge drinking (Stickley, Koyanagi, Koposov, Schwab-Stone, & Ruchkin, 2014), but in college students (18–29 years old) perceived stress predicted binge drinking two weeks later (Chen & Feeley, 2015). Regarding mood, an initial study indicated that binge drinkers (18–30 years old) reported less positive mood than non-binge drinkers (Townshend & Duka, 2005), but results were not supported in other studies among similar populations (Hartley et al., 2004; Scaife & Duka, 2009). Another study evaluating mood considered the effects of school-related stress and sex in college students (mean age: 20.83 years old). In men, school-related stress was indirectly related to binge drinking through its positive relation with depressive mood, which was directly related to binge drinking. In women, depressive mood was indirectly related to binge drinking through school stress, which was directly and negatively related to binge drinking (Pedersen, 2013). The relationship between binge drinking and mood is thus influenced by stress and differs according to sex. Interestingly, a study evaluated whether alcohol abstinence was related to negative mood in young binge drinkers (16–18 years old). The prevalence of negative mood was related to the specific number of drinks consumed on one occasion and to the total number of drinks consumed before the abstinence period (Bekman et al., 2013). Further, depressive and anxiety symptoms were more pronounced in binge drinkers than in non-binge drinkers during the early stages of abstinence (before 4 weeks) but disappeared by the end of abstinence. In general, these studies suggest that current emotional states (loneliness, stress, mood) are associated with binge drinking and with early stage of alcohol abstinence in binge drinkers, but relevant parameters including age and the type of emotional states need to be determined.

Additional studies have explored whether mood impairments were observed after drinking alcohol at binge levels (acute alcohol consumption). Rose and Grunsell (2008) showed that mood evaluation differed between binge drinkers and non-binge drinkers (18–25 years old) following both alcohol and placebo intakes. Binge drinkers showed diminished feelings of stimulation in the placebo condition, and more lightheadedness in the alcohol condition (Rose & Grunsell, 2008). The mood alterations after drinking alcohol were supported and extended by another study indicating impaired mood the morning after drinking alcohol (average of 0.12 g% breath alcohol concentration) in young people (21–24 years old) who presented at least one binge-drinking episode in the past month (Howland et al., 2010). Longitudinally, alcohol consumption affected both positive and negative mood in young adults (21–28 years old), higher alcohol-induced positive mood was associated with more frequent binge drinking and more alcohol-related problems after 18-month, and higher negative mood reduction from alcohol predicted more alcohol-related problems (Venerable & Fairbairn, 2020). Together, these findings suggest that drinking alcohol (acute intoxication) impairs mood in binge drinkers and has implications for understanding differential effects of current and long-term emotional states in binge drinking (long-term effects of alcohol).

Second, cross-sectional studies showed that binge drinking is related to depression and anxiety in different age ranges and countries. In all studies, the diagnosis of depression and anxiety was based on cutoff scores from validated questionnaires but was not formally performed by a psychiatrist. A large-scale study conducted in the United States evaluated the prevalence of binge drinking in adults (18 years old or older) with current or previous depression diagnosis. Participants with current depression or having a lifetime history of depression or anxiety exhibited more binge drinking than controls (Strine et al., 2008). In Thailand, another large-scale study conducted among adolescents (12–17 years old) supported the association between binge drinking and depression, particularly among girls (Wichaidit, Pruphetkaew, & Assanangkornchai, 2020). In South Africa, suicidal thoughts were associated with depression, anxiety, worthlessness, and binge drinking in young men (Mngoma, Ayonrinde, Fergus, Jeeves, & Jolly, 2020). In Uruguayan college students (18–30 years old), however, psychological distress (i.e., anxiety, depression, distress) was not associated with binge drinking but rather with negative alcohol consequences (Ruiz, Pilatti, & Pautassi, 2020). Longitudinal studies enable specifying antecedents of these relations. In college students (mean age of 19.9 years), depressive symptoms predicted binge drinking over one week in women (Mushquash et al., 2013). Longer-term longitudinal studies indicated that sub-clinical anxious and depressive symptoms in the general population (18–74 years old) were related to the onset of AUD but not of binge drinking at 12-month follow-up (Haynes, Farrell, Singleton, Meltzer, & Aya, 2005). However, in the transition from adolescence to adulthood (13–17 years old at baseline), a 13-year longitudinal study specified that depressive symptoms were positively associated with binge drinking (Pape & Norström, 2016). Interestingly, depressive and anxiety symptoms in binge drinkers were related to greater activations in limbic and fronto-striatal regions when viewing alcohol cues compared to other appetitive cues, supporting the relationship between depression, anxiety, and the potential reinforcement of alcohol drinking (Ewing, Filbey, Chandler, & Hutchison, 2010).

Finally, the relationships identified between internal emotional states and binge drinking did not address the specificity of these emotional states in binge drinkers relative to comparison groups (either non-binge drinkers5 or teetotalers6). For example, it has been shown that young adult binge drinkers (18–23 years old) exhibited lower trait-anxiety and depression than teetotalers (Hartley, Elsabagh, & File, 2004). Yet, the comparison between binge drinkers and teetotalers may lead to unexpected results, as teetotalers may exhibit higher levels of somatic anxiety and aggressive mood (Gil-Hernandez & Garcia-Moreno, 2016). Further, in comparison with non-binge drinkers, adolescent binge drinkers (16–18 years old) presented greater anxiety and depressive symptoms (Bekman et al., 2013), but this result was not replicated among young adults (mean age of 21.1; Nourse, Adamshick, & Stoltzfus, 2017).

Interim summary:

The investigation of internal emotional identification shows that both current emotional states as well as depression and anxiety symptoms are related to binge drinking. Overall, findings seem to indicate that loneliness is more prevalent in early adolescence, whereas high stress levels are more frequent in late adolescence. The evaluation of mood leads to consistent results in studies evaluating alcohol drinking and abstinence, showing an augmentation of positive mood immediately after alcohol drinking and the emergence of negative mood the day after drinking or when adolescents quit drinking. Finally, the relation between binge drinking and depression or anxiety is supported in several studies but also seems influenced by other alcohol outcomes, such as severe AUD or alcohol-related problems. These findings are particularly important for healthcare providers, as emotional identification of internal cues is related to binge drinking in prospective studies.

Emotional identification of external cues.

External emotional identification has been investigated in binge drinking by 12 studies using various measures. This subsection has been divided into two categories. First, external emotional appraisal, namely the ability of binge drinkers to appraise emotional situations (e.g., emotional situations or scenes), was measured in two studies. Secondly, emotional identification, the ability of binge drinkers to identify emotional states expressed by other individuals (e.g., emotional faces), was targeted in ten studies. For the sake of clarity, we first describe in each subsection the results obtained with self-reported and behavioral measures, before shifting to the studies based on brain-functioning measures.

Regarding emotional appraisal, a first study underlined that poor self-reported distress appraisal predicted alcohol-related problems in binge drinkers (18–23 years old). This relationship was explained by a propensity to drink to deal with negative emotions (Khan et al., 2018). Then, emotional appraisal was assessed through brain electrophysiological activity (electroencephalographic recordings) while participants rated positive, negative, erotic, and neutral images (Huang, Holcomb, Cruz, & Marinkovic, 2018). Results comparing binge drinkers and non-binge drinkers (18–30 years old) showed no group difference in the self-reported appraisal of emotional images. However, reduced sensitivity in event-related theta power was found in binge drinkers during emotional appraisal, both at early and later processing stages. During emotional appraisal, binge drinkers also presented attenuated differences between neutral and emotional conditions in comparison with non-binge drinkers. This indicates that attentional resources during emotional appraisal are reduced in binge drinkers, potentially limiting their ability to evaluate and react to emotional stimuli accurately (Huang et al., 2018).

Regarding the identification of others’ emotional states, recent studies present behavioral insights about the binge drinkers’ abilities to identify and recognize emotional expressions. Performing a crossmodal identification task (facial and vocal stimuli depicting anger and happiness), binge drinkers did not differ from non-binge drinkers (18–23 years old; Lannoy, Dormal, Brion, Billieux, & Maurage, 2017). However, in a more complex task, binge drinkers (18–27 years old) exhibited poorer performance than non-binge drinkers in recognizing emotional categories presented at different intensities (Lannoy et al., 2018b). This first study produced a group effect nonspecific to emotional category, whereas a second exploration in a larger sample specified that binge drinkers had impairments in recognizing fear and sadness (Lannoy et al., 2019). Individual single-case analyses have also been conducted in this larger sample to explore the percentage of binge drinkers who actually presented a clinically significant emotional recognition deficit compared to a group of matched control participants: 21.15% of binge drinkers were identified as having a deficit for fear recognition and 15.38% for sadness recognition. These studies thus illustrate that binge drinkers have overall difficulties to recognize emotions, while clinical deficits were identified in a subsample of binge drinkers. Then, comparing binge drinkers of different intensities (high and low binge-drinking score) among college students (mean age of 21.2) and youth (mean age of 15.4), another study indicated that low binge drinkers had difficulties to detect sadness whereas high binge drinkers correctly detected sadness but poorly recognized fear (Leganes-Fonteneau, Pi-Ruano & Tejero, 2019). Finally, evaluating the impact of emotional processing on memory, it has been shown that college students with binge drinking (18–20 years old) had a negative emotional recall bias. Results showed no significant effects in males but an emotional memory bias for negative words in females; i.e., higher recall of negative words, increased false alarms for negative emotional distractors, and lower recall of positive and neutral words (Carbia, Corral, Caamaño-Isorna, & Cadaveira, 2020). These findings thus support the proposal of impaired processing of external emotional contents in binge drinkers and show possible specific difficulties with negative emotions.

In addition to these results, studies have evaluated emotional identification through electrophysiological brain measures. Indeed, behavioral studies were not always able to detect subtle differences between binge drinkers and healthy controls (e.g., Lannoy et al., 2017). Electrophysiological measures thus offer a complementary observation of the brain correlates during external emotional identification. Ehlers and colleagues (2007) focused on young adults who had experienced at least one binge drinking episode or had both binge drinking and drug use histories and compared them to non-bingeing and non-drug-consuming controls (18–25 years old). Electrophysiological activity was explored during the identification of happy, sad, and neutral faces, and results suggested a reduced recruitment of attentional resources during emotional identification in young adults with a binge drinking history (i.e., decreased amplitude of the late P3 component). Young adults with binge drinking and drug history also depicted a faster latency of the early P3 component for all stimuli compared with controls, this being interpreted as a possible effect of alcohol and drug use on developmental changes in the P3. Another study (Lannoy et al., 2018c) explored emotional crossmodal integration as described above and showed differences in electrophysiological activity in binge drinkers compared to both teetotalers and non-binge drinkers (18–29 years old). In particular, greater brain activity was observed for anger processing than for happiness in binge drinkers, they also presented increased brain activity during incongruency (e.g., a happy face presented together with an angry voice). Differences in electrophysiological activity were finally observed when binge drinkers had to process vocal stimuli consisting of the emotional enunciation of a semantically neutral word. Results indicated that after nine months of binge drinking, participants (mean age of 18.17 years old at baseline) who did not present a binge drinking pattern at baseline depicted delayed latency of the ERP components related to early perceptive-attentional (P1, N2) and late decision-related (P3) processing (Maurage, Pesenti, Philippot, Joassin, & Campanella, 2009), supporting that short-term binge drinking lead to modification of brain activity during emotional identification of anger and fear.

Eventually, the occurrence of brain modifications during emotional identification has been supported by a neuroimaging study (Maurage, Bestelmeyer, Rouger, Charest, & Belin, 2013b) that used morphed auditory stimuli (fear-anger continuum). Relative to non-binge drinkers, binge drinkers (19–32 years old) presented poorer ability to categorize emotional contents at the behavioral level and disrupted brain activation during emotional identification, namely lower activation of the bilateral superior temporal gyrus and increased activation of the right middle frontal gyrus. Authors proposed that the lower temporal activation observed in bingers indicated an impaired processing of affective sounds, whereas the greater frontal activation reflected a compensatory activity. Brain responses during emotional identification (i.e., emotional faces of anger, fear, or neutral expressions) were also used to classify binge drinkers and non-binge drinkers (22–35 years old) using machine learning algorithms. Results, however, showed that emotional processes were not among the variables offering a reliable distinction between groups. Neural correlates of social cognition were conversely related to a trustworthy group classification (Gowin, Manza, Ramchandani, & Volkow, 2020).

Interim summary:

The investigation of external emotional identification highlights emotional difficulties related to binge drinking. Emotional appraisal was only documented in two studies. Results showed lower attentional resources to appraise emotional images in binge drinkers, while poor appraisal of distress was related to alcohol-related problems. Lower attentional resources to identify emotional images were also linked to binge drinking. Regarding facial expressions processing, findings highlight consistent difficulties to recognize fear, while impairments in the recognition of sadness need to be further supported. Brain activity during emotional facial expressions processing appear to be disturbed in binge drinking, but this impairment is not sufficient to distinguish binge drinkers from non-binge drinkers. In order to delineate clinical perspectives, longitudinal findings are still needed to determine whether disrupted external emotional identification is a consequence of binge drinking (alcohol’s effect on the brain) and/or a risk factor for excessive drinking.

3.2.2. Emotional Response (Table 3)

Table 3.

Description and main results of studies evaluating emotional response in binge drinking.

| Authors (year) | Participants | Intervention | Comparator | Experimental design | Outcomes | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (n) | Age | Gender ratio (% of males) | Inclusion criteria | Binge drinking criteria | Control group/variable | Processes measured | Task/scale | Stimuli | Main results | Limits | ||