Abstract

Chronic diseases are a major health problem and cause of death worldwide. Patients with chronic diseases should be managed by an interprofessional care team consisting of general practitioners, medical specialists, nurses, and pharmacists. However, the roles of pharmacists in this interprofessional care team have not been fully explored. This study, therefore, examined their roles as members of the interprofessional care team in managing patients with chronic diseases. A search in PubMed, Google Scholar, EBSCO, Scopus, and Cochrane Library databases was conducted for research articles that discussed pharmacists, interprofessional healthcare, and chronic diseases. From initial 420 identified articles, a total of 27 articles were included in this study. The interprofessional healthcare team should have a sense of tolerance and belonging among its members, which is reflected in five dimensions: partnership, coordination, cooperation, decision-making, and therapeutic outcomes. The five dimensions are closely related because they support each other in the success of the therapy. The presence of pharmacists in an interprofessional healthcare team has been proven to help facilitate access to primary care and improve patient outcomes. Pharmacists can assist in managing chronic disease conditions by providing drug information to patients and other healthcare providers and by acting as a consultant for treatment-related issues. The pharmacist’s role as part of an interprofessional care team reinforces the importance of a collaborative healthcare team in providing clinical services to patients with chronic diseases.

Keywords: pharmacist, interprofessional care, chronic diseases, health care

Introduction

Chronic disease has become a public health burden and one of the leading causes of mortality and disability. In hospitals, chronic diseases are managed by an interprofessional care team led by a medical doctor and can include general practitioners, medical specialists, nurses, pharmacists, psychologists, and other medical professionals.1 Specialists are involved as consultants when their role is limited to providing diagnostic advice to primary care physicians or conducting diagnostic and curative technical interventions without providing ongoing management of the health problems.2 In an interprofessional care team, disputes and work fatigue can occur if their work is not supported by good communication, cooperation, and coordination.3 Therefore, involving the team members in the decision-making process will provide creative solutions and provide them with the opportunity to contribute in their respected field.3

Pharmacists can help improve chronic disease management and prevent drug administration errors. Pharmacists are responsible for a variety of patient activities such as reconciling medication, detecting drug interactions, checking laboratory tests to monitor drug therapy and prescribed medications, extending prescriptions, and imparting patient education. Pharmacists advocate for the patient when prescriptions might no longer be indicated or might no longer provide a benefit.4 Although pharmacists have limited resources in terms of time and funding for patient follow-up outside of clinic hours, they often work on nonclinical days to follow-up with patients with treatment problems or at the request of nurses and doctors.4

The presence of pharmacists in the interprofessional care team should have a positive impact on the patient’s recovery, including helping reduce medical costs for prescription medications and increasing the rationality of the therapy for patients with chronic diseases. However, the current roles of pharmacists in this team are still poorly studied and have not been fully explored. This review therefore discusses the pharmacists’ contribution as members of the interprofessional care team in managing patients with chronic diseases from several perspectives including partnership, coordination, collaboration, joint decision-making, and therapeutic outcomes.5

Methods

Our review was based on articles published during 2010–2020 and obtained from PubMed, Google Scholar, EBSCO, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library, using the keywords “pharmacist,” “interprofessional healthcare,” and “chronic disease.” The search was performed from November to December 2020. After the initial article identification, review articles and articles that did not discuss pharmacists were excluded from the study.

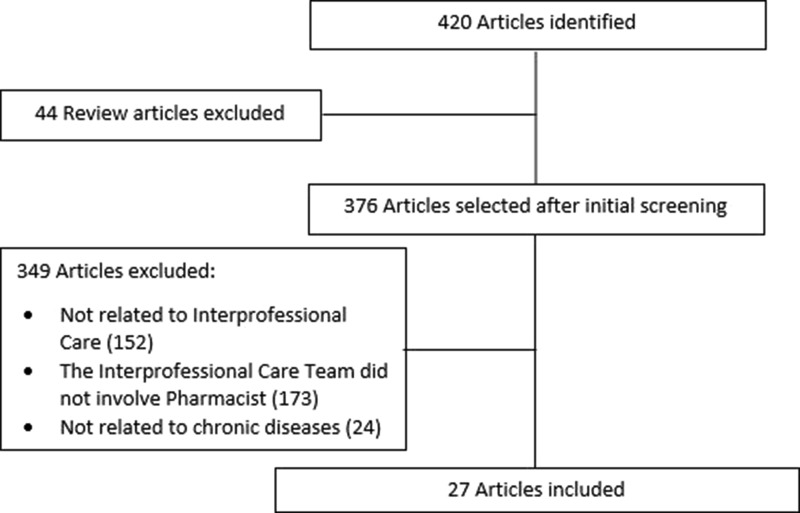

As described in Figure 1, the search resulted in 420 articles, 44 of which were excluded because they were reviews, 152 were excluded because they were not related to interprofessional care, 173 were excluded because the interprofessional care team did not involve pharmacist, and 24 were further excluded because they were not related to chronic diseases. Ultimately, 27 articles that discussed interprofessional healthcare, pharmacists, and chronic disease were available for review (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature search.

Table 1.

Interprofessional Care Dimensions Discussed in This Study

| No | Reference | Interprofessional Care Team | Study Sites | Interprofessional Care Dimension Discussed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partnership | Coordination | Cooperation | Shared Decision-Making | Therapeutic Outcome | ||||

| 1 | Guilcher et al6 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Toronto, Canada | – | – | ✓ | – | – |

| 2 | Cain et al3 | Doctor, nurse, pharmacist, family therapist, pastor | USA | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| 3 | Powell et al7 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Philadelphia, USA | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – |

| 4 | Wodskou et al8 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Denmark | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| 5 | Probst et al9 | Physical therapist, doctor, nurse, pharmacist, nutritionist | Switzerland | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – |

| 6 | Lehnbom et al10 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Sydney, Australia | – | – | ✓ | – | – |

| 7 | Gordon et al11 | Doctor, pharmacist | USA | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| 8 | Zschoche et al12 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Maryland, USA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| 9 | Cope et al13 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | New York, USA | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| 10 | Silvaggi et al14 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | UK | – | ✓ | – | – | – |

| 11 | Ulrich et al15 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Germany | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – |

| 12 | Lublóy et al16 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Canada | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – |

| 13 | Smith et al17 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Ireland | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| 14 | Lelubre et al18 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Switzerland | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – |

| 15 | Chan et al19 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Sydney, Australia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| 16 | Santschi et al20 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Switzerland | – | – | ✓ | – | – |

| 17 | Turner et al21 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | USA | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| 18 | deBoer et al22 | Physical therapy doctor, doctor, nurse, pharmacist, psychologist, social workers, dietitians | Toronto, Ontario | – | – | ✓ | – | – |

| 19 | Swanoski et al23 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse practitioners, physician assistants | USA | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – |

| 20 | DiMaria-Ghalili et al24 | Doctors, nurses, pharmacists, dentists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech and language pathologists | USA | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – |

| 21 | Higgins et al25 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Virginia, USA | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – |

| 22 | Coffey et al26 | Doctor, pharmacist | Ohio, USA | – | – | ✓ | – | |

| 23 | Taylor et al27 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Arizona, USA | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – |

| 24 | Boylan et al28 | Doctors, pharmacists, nurses, medical assistants, and health coaches | Florida, USA | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| 25 | Swallow et al29 | Clinical psychologists, dietitians, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, play workers, therapists, and social workers | UK | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – |

| 26 | Rieck et al31 | Doctor, pharmacist | Perth, Australia | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| 27 | Lalonde et al31 | Doctor, pharmacist, nurse | Canada | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – |

This review discusses the interprofessional collaboration based on the following dimensions of collaboration, namely coordination, cooperation, joint decision making, and partnership.5 Given that the outcomes for interprofessional care teams are improvements in patient clinical outcomes, we also included clinical outcomes as the fifth dimension to assess the success of patient therapy in improving outcomes.

Chronic Diseases

Chronic diseases are the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in Europe. Chronic illness lowers wages, incomes, labor participation, and productivity and increases early retirement, high turnover, and disability. The increasing spending on long-term care across Europe will require an increasing proportion of public and private resources. Generally, chronic diseases include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Given that survival rates and illness duration have increased, several other types of diseases need to be considered as chronic conditions, including various types of cancer, HIV/AIDS, mental illness (such as depression, schizophrenia, and dementia), and disabilities such as visual impairment. Numerous chronic diseases and conditions are associated with an aging society; however, lifestyle choices such as smoking, sexual behavior, diet, exercise, and genetic predisposition are also associated. Chronic diseases are long-term diseases that require a complex response coordinated by multiple health professionals with access to necessary medicines, equipment, and social care.6 This review investigated the interprofessional collaboration in chronic disease treatment from five dimensions: partnership, coordination, cooperation, shared decision-making, and therapeutic outcomes.

Partnership

Interprofessional healthcare teams include community health workers, care managers, and social workers who work directly with patients to guide and manage complex systems and meet health-related needs and reduce barriers to good health.7 Interprofessional healthcare teams develop interdisciplinary educational interventions (nursing, physical therapy, and nutrition) to evaluate patients’ eligibility to receive standard care and ensure patient adherence to therapy.8 Each healthcare professional should have a positive attitude toward the other professionals in the team, being comfortable should a specific service be performed by another health professional (eg, drug therapy management and therapy management services by pharmacists).9

In one working group, clinical pharmacists and pharmacist administrators collaborated with doctors and nursing staff leaders to identify high-risk patient populations and facilitate the prescribing and dispensing of naloxone.10 The presence of an interprofessional healthcare team, namely doctors, pharmacists, nurses, and social workers, resulted in patients showing a preference for a particular healthcare location for their care.11

The team included various types of professions, with a team that actually collaborated with each other. This collaboration required a certain level of openness, a willingness to compromise, and a clear understanding of each person’s role.12 The collaboration formed in an interprofessional healthcare team can consist not only of various organizations but can also include various age groups. A junior doctor in partnership with a senior nurse was able to distribute health and patient care information through clear lines of authority within the nursing profession.13 Another type of professional who was also part of the interprofessional health care team was a pharmacist who participated in team-based care to build network ties with health providers (eg, doctors and nurses in health and social service institutions).14

Pharmacists as partners in an interprofessional healthcare team were of benefit in managing chronic disease conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, as well as in assisting in smoking cessation programs.15 Health professionals who were also part of the interprofessional healthcare team (doctors and nurses) contacted pharmacists to implement interprofessional treatment adherence strategies for non-compliant patients in their medical practice at their hospital.16 Doctors, nurses, pharmacists, dentists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and speech and language pathologists can positively influence patient care by aligning and reinforcing the importance of nutrition in all specialization areas.15

A team of interprofessional and multidisciplinary healthcare providers (called an interprofessional healthcare team) was formed from prescribers and non-prescribers to comprehensively evaluate prescribing practices.17 An interprofessional healthcare team consisting of doctors, pharmacists, nurses, medical assistants, and health coaches worked with patients with chronic diseases such as COPD and heart failure. The team reviewed and approved the development of self-management kits for COPD and heart failure.18

Hospital-based multidisciplinary teams consisting of professionals with special expertise in a particular health condition formed partnerships with the parents of children with chronic conditions (eg, chronic kidney disease).19 Doctors followed up on pharmacist recommendations regarding medication management and suggested reducing the separation of powers, given that the doctors considered the pharmacists as partners.20 The interprofessional healthcare team implemented collaborative practices to provide appropriate support for changes in a patient’s lifestyle for a faster recovery and return to health.21

Partnerships in interprofessional care strengthened the roles of team members. Pharmacists as part of interprofessional care teams performed their role well when supported by other professionals on the team.

Coordination

Members of the interprofessional healthcare team supported the other members by paying attention to work aspects that occupied and energized the members.3 Interprofessional healthcare teams provide a wide range of services, including patient needs assessments, coordination of services and interventions, and patient follow-up and advocacy.7

In a healthcare setting, a general practitioner, nurse, and pharmacist can contact patients with COPD and develop new action plans to facilitate the transition from hospital to a residence.22 Another form of interprofessional teamwork is the hospital working group reported by Johns Hopkins Hospital that identifies barriers to prescribing outpatient naloxone and to develop and implement policies that consistently outline the approach to prescribing naloxone in an outpatient clinic.10 Together with primary care providers, pharmacists are directly involved in drug management and procurement, including antiretroviral drugs.11

Coordination with other healthcare professionals is important because the pharmacist’s role often overlaps with that of other healthcare professionals, which sometimes leads to conflicts between team members.23 Efficient coordination of an interprofessional healthcare team results in patients having lower treatment costs due to efficient use of health services.24 Junior doctors, senior nurses, and pharmacists have coordinated an efficient increase in deploying new interventions.13

Doctors, nurses, pharmacists, dentists, and others who are part of an interprofessional healthcare team have a positive influence on patient care by synchronizing and strengthening the importance of nutrition in all areas.25 The integral role of pharmacists and interprofessional healthcare team coordinators reinforces the importance of these collaborative healthcare teams in providing clinical services to assist patients in managing chronic diseases.26 Professionals reinforce information given to other members or to the patient’s parents or family. This division of labor is combined with the tacit understanding that each member supports the other.19 Patients with multiple morbidities have been treated through interprofessional collaboration, with referrals coordinated by nurses.21

Managing patients with chronic disease conditions requires good coordination from each healthcare provider. Each professional participates according to their field and avoids conflict with the other professionals, making patient recovery their main goal.

Cooperation

Collaboration in tailoring treatment, providing education, and exploring treatment options has been part of the work of interprofessional healthcare teams.27 Collaboration in tailoring care for each patient is important for interprofessional healthcare teams.3 Cooperation in treating patients with severe diseases is affected by the professional cooperation of a comprehensive health team in several areas of the health system.22 For example, a primary care doctor and pharmacist can jointly treat patients with multimorbidity.28

Heinen et al collaborated to develop and evaluate a counseling program to increase therapeutic adherence and physical activity in patients with leg ulcers.29 In a public hospital in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, an infectious disease doctor and a nurse implemented interprofessional treatment adherence for patients with chronic diseases and collaborated with community pharmacies.30 Healthcare teams with primary care prescribers (physicians, nursing practitioners, and physician assistants) and pharmacists working together at the clinical level and at the professional development level have made major strides in reducing the prescribing of potentially inappropriate drugs, thereby increasing patient safety.17

Collaboration in establishing communication between multidisciplinary team members is essential to maintaining the quality of drug use among patients in geriatric medicine wards.13 In HIV care, the importance of cooperation between rehabilitation professionals and HIV specialists (nurses, doctors, social workers, pharmacists, psychologists, and dietitians) can prevent disabilities experienced by adults living with HIV by providing physical therapy services.31 In another case, the intervention of an interprofessional healthcare team involving nurses, pharmacists, and doctors had far superior results in outpatient hypertension control.32 The interprofessional healthcare team also collaborated and coordinated with outpatient pharmacies to enable control of the distribution of naloxone prescriptions.10

Doctors and pharmacists have cultivated strong relationships to enhance cooperation and increased collaboration regarding treatment management and overall patient management.20 Interprofessional healthcare teams have provided comprehensive, population-based, patient-centered primary care,12 and they have worked together to evaluate medicines in patient kits to continuously improve their quality.18 Interprofessional healthcare teams have also reviewed home-based care recommended by general practitioners and pharmacists. A home-based care review involves the referral of a general practitioner to a patient and a patient to a pharmacist. The patient consultation was preferably done in the patient’s home.32

Collaboration of pharmacists within interprofessional care for handling patients has provided better results compared to that without pharmacists in interprofessional care. The role played by each member of an interprofessional care team can improve patient care.

Shared Decision Making

Interprofessional healthcare teams involve team members in the decision-making process to provide creative solutions and make use of the skills of its members.3 The complex activities present in healthcare settings require interaction between parties, including accurate clinical information, effective communication, appropriate follow-up, and joint decision making.24 The proactive involvement of doctors as the primary referral source and as coordinators of interprofessional healthcare teams has been the key to successful recruitment, patient participation, and implementation of health programs.26 Doctors typically have a broader range of medical knowledge and expertise than other health professionals and therefore can have significant influence on the primary healthcare system.20 Doctors have been the center of medical decision making because they tend to communicate well in professional groups.13

In one case, doctors suggested that community pharmacists should provide advice on drug management.28 Pharmacists were able to optimize therapy for patients by starting new medications, stopping treatment, or changing the dosage of treatment regimens.15 The involvement of pharmacists resulted in a decrease in the mean pain score in an underserved population.34 The pharmacist was responsible for providing interprofessional education to all members of the interprofessional healthcare team.18 However, some patients’ therapy was deliberately stopped without confirmation by the interprofessional care team.11

The leader of the interprofessional healthcare team is the decision maker when it comes to the choice of therapy. When dealing with patients, the members of the team need to find consensus with the interprofessional care leader, who is usually a doctor.

Therapeutic Outcome

Chronic disease can be treated in various ways including surgery, physical therapy, psychological therapy, radiotherapy, and drug therapy. In Australia and other developed countries, drug therapy constitutes one of the largest healthcare expenses. Preventing and treating chronic disease will involve large amounts of drugs, which will incur a high cost.35

Pharmacists who treat patients with chronic disease play numerous roles, clinically and non-clinically. Pharmacists in the United States not only provide drugs but also participate in treatment and optimize therapies. Pharmacists who are members of an interprofessional care team can improve patient safety by increasing the focus on the patient’s drug therapy.36

Chronic disease often requires complex treatment and can therefore increase patient non-compliance in taking medication, which can lead to adverse effects, drug interactions, increased treatment costs and patient confusion. Pharmacists who work in interprofessional care teams can offer solutions to encourage patient therapeutic adherence, thereby improving clinical outcomes and reducing adverse effects and treatment costs.37

Patients with chronic disease treated by interprofessional care teams show better therapeutic results and are more satisfied with the services provided than patients treated only by individual professionals.

Discussion and Future Perspective

Our review showed that pharmacists significantly contribute to interprofessional care teams in assuring the accuracy of the drug therapy, thereby decreasing hospital stays and healthcare expenditures.

Interprofessional care teams require various collaborative aspects, including trust between team members and willingness to cooperate. Interprofessional care teams consisting of various health professionals need to identify the aspects of cooperation required for patient-oriented care. In a collaborative system, the goals are determined by the leaders of the interprofessional care team. The action plan in the patient care process is the starting point, which, after being implemented, will need to be evaluated. Effective interprofessional care will be achieved through the professional competency of the interprofessional care team, which will continue to develop and will increase the team’s professionalism.38

The interprofessional healthcare team should have a sense of belonging among its members, which, as noted earlier, is reflected in five dimensions: partnership, coordination, cooperation, decision-making, and therapeutic outcomes. These dimensions describe the performance of an interprofessional healthcare team in treating patients with chronic diseases and are closely related because each dimension supports the other.

Coordination is a matter of regulating the activities so that the rules and actions to be implemented do not conflict with each other. Another important aspect underlying an effective team is communication. Relational coordination theory states that in order for a team to be effectively coordinated, knowledge and understanding need to be shared among the team, and a relationship needs to be built based on common goals and mutual respect.39 The interprofessional healthcare team has the same goal every step of the way, namely for patients to return to better health. The variety of professions within an interprofessional healthcare team requires each team member to have a high degree of mutual trust and respect. They share patients’ medical information with each other, so that no information is hidden when providing patient clinical information. Research data has shown that effective nurse-doctor collaborations can improve the quality of patient care, decrease patient morbidity and mortality, and increase patient satisfaction. For healthcare personnel, collaboration can increase job satisfaction and retention. Interprofessional coordination is like collaboration in terms of a shared identity. However, integration and interdependence are seen as less important. Team tasks are perceived as more predictable, less urgent, and less complex. However, coordination is perceived as similar to collaboration, because it requires joint accountability among individuals, as well as clarity of roles, tasks, and goals.40

Cooperation is defined as a form of joint effort conducted by several people to achieve common goals. Collaboration in an interprofessional healthcare team involves collective actions to address complex patient needs. The quality of interprofessional collaboration in health care should be a major concern, given that it has an immediate impact on patient outcomes.

A patient’s lack of competence in participating in joint decision making is often a barrier. However, information on the disease and treatment provided to patients involves healthcare providers of all professions, because healthcare providers can also be facilitators in joint decision making. To help interprofessional healthcare teams make joint decisions, the importance of improving mental health expertise among general practitioners and community pharmacists should also be emphasized. General health workers stress the importance of sharing information between providers and settings, because health care is the key to successful joint decision making in patient care.41

Improving the practice of interprofessional health care teams is a way to improve the quality of care, reduce the costs of care, and improve patient therapy outcomes. One reason for the failed attempts to improve the practice of interprofessional healthcare teams is a lack of a conceptual framework for unifying teamwork. Unraveling the complexities of how interprofessional healthcare teams work will help in understanding interprofessional practices and in designing the interventions needed to improve outcomes.42

Our study has certain limitations. First, from the numerous dimensions of interprofessional collaborations, we only discussed five dimensions that have been reported to directly contribute to collaboration in healthcare. Second, due to the lack of available studies on the specific research question on the roles of pharmacists in interprofessional care teams, we did not perform a systematic review. Instead, we performed a literature review to provide a qualitative summary of the roles of pharmacists in interprofessional care teams.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations, this literature review showed that pharmacists make an important contribution to interprofessional care teams in providing clinical services to help patients manage chronic diseases. Pharmacists can work in a team, coordinating care, building partnerships, making the best decisions in setting goals, and improving patient therapeutic outcomes.

Acknowledgments

SAR received a BPPDN doctoral program scholarship from The Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts on interest in this work.

References

- 1.Rotenstein LS, Sadun R, Jena AB. Why doctors need leadership training. Harvard Bus Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larochelle J-L, Feldman D, Levesque J-F. The primary-specialty care interface in chronic diseases: patient and practice characteristics associated with co-management. Healthc Policy. 2014;10:52–63. doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2015.24036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cain CL, Taborda-Whitt C, Frazer M, et al. A mixed methods study of emotional exhaustion: energizing and depleting work within an innovative healthcare team. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(6):714–724. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1356809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alim U, Austin-Bishop N, Cummings G. Pharmacists in a complex chronic disease management clinic. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2016;69(6):480–482. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v69i6.1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orchard CA, King GA, Khalili H, Bezzina MB. Assesment of interprofessional team collaboration scale (AITCS): development and testing of the instrument. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2012;32:58–67. doi: 10.1002/chp.21123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busse R, Blümel M, Scheller-Kreinsen D, Zentner A. Tackling chronic disease in Europe. Strategies, interventions and challenges. Vol 2009; 2010. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/96632/E93736.pdf. Accessed June1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell RE, Doty A, Casten RJ, Rovner BW, Rising KL. A qualitative analysis of interprofessional healthcare team members’ perceptions of patient barriers to healthcare engagement. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1). doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1751-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Probst S, Allet L, Depeyre J, Colin S, Buehrer Skinner M. A targeted interprofessional educational intervention to address therapeutic adherence of venous leg ulcer persons (TIEIVLU): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1). doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3333-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon C, Unni E, Montuoro J, Ogborn DB. Community pharmacist-led clinical services: physician’s understanding, perceptions and readiness to collaborate in a Midwestern state in the United States. Int J Pharm Pract. 2018;26(5):407–413. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zschoche JH, Nesbit S, Murtaza U, et al. Development and implementation of procedures for outpatient naloxone prescribing at a large academic medical center. Am J Health Pharm. 2018;75(22):1812–1820. doi: 10.2146/ajhp170759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cope R, Berkowitz L, Arcebido R, Yeh J-Y, Trustman N, Cha A. Evaluating the effects of an interdisciplinary practice model with pharmacist collaboration on HIV patient co-morbidities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(8):445–453. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulrich L-R, Pham T-NT, Gerlach FM, Erler A. Family health teams in Ontario: ideas for Germany from a Canadian primary care model. Gesundheitswesen. 2019;81(6):492–497. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-111406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan B, Reeve E, Matthews S, et al. Medicine information exchange networks among healthcare professionals and prescribing in geriatric medicine wards. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(6):1185–1196. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner K, Weinberger M, Renfro C, et al. The role of network ties to support implementation of a community pharmacy enhanced services network. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15(9):1118–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins KL, Hauck FR, Tanabe K, Tingen J. Role of the ambulatory care clinical pharmacist in management of a refugee patient population at a university-based refugee healthcare clinic. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;22(1):17–21. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00879-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lelubre M, Clerc O, Grosjean M, et al. Implementation study of an interprofessional medication adherence program for HIV patients in Switzerland: quantitative and qualitative implementation results. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1). doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3641-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swanoski MT, Little MM, St Hill CA, Ware KB, Chapman S, Lutfiyya MN. Potentially inappropriate medication prescribing in U.S. older adults with selected chronic conditions. Consult Pharm J Am Soc Consult Pharm. 2017;32(9):525–534. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2017.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boylan P, Joseph T, Hale G, Moreau C, Seamon M, Jones R. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure self-management kits for outpatient transitions of care. Consult Pharm J Am Soc Consult Pharm. 2018;33(3):152–158. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2018.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swallow V, Smith T, Webb NJA, et al. Distributed expertise: qualitative study of a British network of multidisciplinary teams supporting parents of children with chronic kidney disease. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41(1):67–75. doi: 10.1111/cch.12141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rieck AM. Exploring the nature of power distance on general practitioner and community pharmacist relations in a chronic disease management context. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(5):440–446. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.906390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lalonde L, Goudreau J, Duhamel F, Be D, Le L. Priorities for action to improve cardiovascular preventive care of patients with multimorbid conditions in primary care — a participatory action research project. Fam Pract. 2012;1–9. DOI: 10.1093/fampra/cms021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wodskou PM, Høst D, Godtfredsen NS, Frølich A. A qualitative study of integrated care from the perspectives of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their relatives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1). doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silvaggi A, Nabhani-Gebara S, Reeves S. Expanding pharmacy roles and the interprofessional experience in primary healthcare: a qualitative study. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(1):110–111. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2016.1249281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lublóy Á, Keresztúri JL, Benedek G. Formal professional relationships between general practitioners and specialists in shared care: possible associations with patient health and pharmacy costs. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2016;14(2):217–227. doi: 10.1007/s40258-015-0206-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiMaria-Ghalili RA, Mirtallo JM, Tobin BW, Hark L, Van Horn L, Palmer CA. Challenges and opportunities for nutrition education and training in the health care professions: intraprofessional and interprofessional call to action. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(5):1184S–93S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.073536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor AM, Bingham J, Schussel K, et al. Integrating innovative telehealth solutions into an interprofessional team-delivered chronic care management pilot program. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(8):813–818. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.8.813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guilcher SJT, Everall AC, Patel T, et al. “The strategies are the same, the problems may be different”: a qualitative study exploring the experiences of healthcare and service providers with medication therapy management for individuals with spinal cord injury/dysfunction. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1). doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1550-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith SM, O’Kelly S, O’Dowd T. GPs’ and pharmacists’ experiences of managing multimorbidity: a “Pandora’s box”. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(576):e285–e294. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X514756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heinen MM, Van Achterberg T, Scholte Op Reimer W, Van De Kerkhof PCM, De Laat E. Venous leg ulcer patients: A review of the literature on lifestyle and pain-related interventions. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(3):355– 366. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00887.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lelubre M, Clerc O, Grosjean M, et al. Implementation of an interprofessional medication adherence program for HIV patients: description of the process using the framework for the implementation of services in pharmacy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):698. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3509-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.deBoer H, Andrews M, Cudd S, et al. Where and how does physical therapy fit? Integrating physical therapy into interprofessional HIV care. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(15):1768–1777. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1448469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santschi V, Wuerzner G, Chiolero A, et al. Team-based care for improving hypertension management among outpatients (TBC-HTA): study protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1). doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0472-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehnbom EC, Brien J-AE. Challenges in chronic illness management: a qualitative study of Australian pharmacists’ perspectives. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32(5):631–636. doi: 10.1007/s11096-010-9414-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coffey CP, Ulbrich TR, Baughman K, Awad MH. The effect of an interprofessional pain service on nonmalignant pain control. Am J Health Pharm. 2019;76(Supplement_2):S49–S54. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxy084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sav A, King MA, Whitty JA, et al. Burden of treatment for chronic illness: a concept analysis and review of the literature. Health Expect. 2015;18(3):312–324. doi: 10.1111/hex.12046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daly CJ, Quinn B, Mak A, Jacobs DM. Community pharmacists’ perceptions of patient care services within an enhanced service network. Pharmacy. 2020;8(3):172. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy8030172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Bittner MR, Zaghab RW. Improving the lives of patients with chronic diseases: pharmacists as a solution. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(2):429–436. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pärnä K. Kehittävä Moniammatillinen Yhteistyö Prosessina. Scripta Lingua Fennica Edita, Uniprint Oy Turku; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hustoft M, Biringer E, Gjesdal S, Aßus J, Hetlevik Ø. Relational coordination in interprofessional teams and its effect on patient-reported benefit and continuity of care: a prospective cohort study from rehabilitation centres in Western Norway 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Ser. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3536-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reeves S, Xyrichis A, Zwarenstein M. Teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking: why we need to distinguish between different types of interprofessional practice. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(1):1–3. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1400150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF. Shared decision-making and interprofessional collaboration in mental healthcare: a qualitative study exploring perceptions of barriers and facilitators. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(5):373–379. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.785503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freeman JB. Doing psychological science by hand. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2018;27(5):315–323. doi: 10.1177/0963721417746793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]