Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to investigate the knowledge, attitudes and willingness of nursing students to receive the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccine and the influencing factors.

Background

Vaccination is one of the most effective measures to prevent COVID-19, but the vaccination acceptance rate varies across countries and populations. As trustworthy healthcare providers, nursing students’ attitudes, knowledge and willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine may greatly affect the present and future vaccine acceptance rates of the population; however, studies related to the vaccine acceptance rates among nursing students are limited.

Methods

A convenience sampling method was adopted to select two medical universities in China. Following the cluster sampling method, nursing college students who were eligible for the study were selected. A cross-sectional survey was conducted by asking nursing students to complete an online questionnaire from February to April 2021. Descriptive statistics, t-tests/one-way analysis of variance (normal distribution), U tests/H tests (skewness distribution) and multivariate linear regression were performed.

Results

A total of 1488 valid questionnaires were collected. The score rates of the attitude, knowledge and vaccination willingness dimensions were 70.07%, 80.70% and 84.38%, respectively. Attitude was significantly influenced by vaccination status of family members. The main factors influencing knowledge were gender, grade and academic background. In terms of willingness, gender, academic background, visits to high-risk areas, vaccination status of family members and the side effects experienced after receiving other vaccines were significant influencing factors.

Conclusions

Nursing students showed satisfactory vaccine acceptance rates. However, more attention should be paid to male students, younger students, those with a medical background, those with low grades and those whose family members had not received the COVID-19 vaccine or had side effects from the vaccine.

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccines, Attitudes, Knowledge, Willingness, Nursing students

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic is a global public health crisis that has a serious impact on the international community. Vaccination is one of the most effective and low-cost measures to prevent COVID-19. Currently, nine COVID-19 vaccines have been approved for marketing worldwide; as of March 15, 2021, more than 360 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been globally administered (WHO, 2021a, WHO, 2021b). Herd immunity is directly proportional to vaccination rate and adequate population immunity can only be achieved if most of the population is vaccinated. However, studies have shown that the willingness to be vaccinated varies across countries and populations after the introduction of the COVID-19 vaccine and is influenced by several factors. Kreps et al. (2020) conducted a survey among adults in the United States, with 69% of the participants showing willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine. They were more willing to receive the vaccine if the healthcare provider recommended it and if the perceived risk and severity of the disease were higher than those of the vaccine side effects. Vaccines with high effectiveness, long protection periods and low incidence of adverse reactions were easily accepted by the population (Kreps et al., 2020, Reiter et al., 2020). Lin et al. (2020) conducted a survey among 3541 residents in China to evaluate the intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. They found that 83.3% of the residents were willing to be vaccinated and their willingness to be vaccinated was influenced by socioeconomic factors. Yoda and Katsuyama (2021) surveyed 1100 Japanese residents and found that 65.7% of the participants were willing to be vaccinated; higher willingness to be vaccinated was reported among older adults, those living in rural areas and those with underlying diseases, but higher hesitation was noted among women. Among healthcare workers, the vaccine acceptance rate ranged from 23.4% in Taiwan to 95% in the Asia-Pacific region (Sallam, 2021, Szmyd et al., 2021, Kukreti et al., 2021, Shaw et al., 2021, Unroe et al., 2021). The side effects after vaccination (Szmyd et al., 2021) and long-term protective efficacy and safety (Shaw et al., 2021) were the main concerns of healthcare workers. Depression (Szmyd et al., 2021), anxiety (Yurttas et al., 2021) and concerns about the vaccines’ side effects (Unroe et al., 2021) were the common factors associated with the reduction in the healthcare workers’ willingness to be vaccinated; meanwhile, disease prevention (Kukreti et al., 2021), fear of transmitting disease to family members (Szmyd et al., 2021), clinical workplace (Shaw et al., 2021), older age, male gender, (Yurttas et al., 2021, Shaw et al., 2021, Unroe et al., 2021) and white race (Yurttas et al., 2021, Unroe et al., 2021) were the main factors associated with increase in the healthcare workers’ willingness to be vaccinated.

In college students, Qiao et al. (2020) surveyed 1062 South Carolina college students and revealed that perception and fear of the outbreak were positively associated with high vaccine acceptance, while higher exposure risk and negative attitudes toward the vaccine were associated with low vaccine acceptance. Graupensperger et al. (2021) conducted an online survey involving 647 college students and found that 91.64% of students were willing to receive the vaccine, indicating a strong willingness to receive the vaccine. However, participants thought that other young people were less likely to receive the vaccine and did not think that vaccination was important. Sun et al. (2020) surveyed 1912 Chinese university students, with 64.01% of them indicating that they were willing to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine trial. Low socioeconomic status, female gender, perceived risk of contracting the disease and prosocial behavior were the main factors promoting willingness to be vaccinated, while hesitation to sign the informed consent form, time required to participate in the study and perceived social stigma of COVID-19 were the primary factors that hindered the participants’ willingness to be vaccinated. Park et al. (2021) surveyed nursing students in seven universities in Greece, Albania, Cyprus, Spain, Italy, the Czech Republic and Kosovo and reported a vaccine acceptability rate of 43.8%. The primary factors that promoted the willingness to be vaccinated were male gender; lack of experience working in a healthcare setting during the pandemic; influenza vaccination in 2019 and 2020; trust in doctors, government and experts; and high level of knowledge and fear of COVID-19. Manning et al. (2021) found that 45.3% of nursing students and 60.3% of full-time teachers intended to be vaccinated and the main reasons for not getting vaccinated were doubts regarding vaccine safety and side effects.

China offers free vaccines for all citizens and the willingness of the population to receive vaccines is key to achieving reasonable vaccination coverage. School nurses are advocates, caregivers and teachers. When people are at their most vulnerable point, school nurses help them make informed decisions and provide essential nursing services (Gordon et al., 2021). As nurses, if they have better knowledge of the COVID-19 vaccine, they can use their personal experience to educate their relatives and friends, the patients they will serve after working in the hospital and the public regarding the importance of receiving the vaccine. As students, if they have good vaccination attitudes and behaviors, they can encourage other students to get vaccinated. Therefore, it is important to understand the nursing students’ perceptions, attitudes and vaccination intentions and to examine the related factors influencing their willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccines, which can assist educational institutions in developing effective interventions to increase the vaccination rate. On reviewing the existing literature, we found that only a few studies have evaluated the college students’ intentions for vaccination, with nursing students being rarely studied; thus, an investigation is imperative. This cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the knowledge, attitudes and intensions for vaccination of Chinese nursing students toward the COVID-19 vaccine and to examine the potential influencing factors to provide evidence for developing effective intervention strategies and improving the vaccination rates.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This cross-sectional survey was conducted using an online questionnaire in February and April 2021. A convenience sampling method was adopted to select two medical universities in mainland China. Following the stratified sampling method, nursing students of different grades were selected.

2.2. Questionnaire

Based on the Guidelines for COVID-19 Vaccination (1st edition) issued by [China NHC], 2021a, , 2021b, the WHO’s “Vaccine Explained” series featuring illustrated articles on vaccine development and distribution (2021) and the guiding principles for immunization activities during the COVID-19 pandemic from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2021), The New York State Department of Health (2021), United States Food and Drug Administration (2021) and the related literature (Qiao et al., 2020, Lin et al., 2020), we developed a questionnaire entitled “Attitude, Knowledge and vaccination Willingness for the COVID-19 vaccine (AKW)” (Supplemental file 1). This questionnaire comprised the following four parts:

-

1.

Questionnaire introductions: including an introduction of the study, anonymity, confidentiality, guidelines for filling in the questionnaire and contact information.

-

2.

Demographic data (14 items): gender, age, nationality, grade, educational level, level of high school education achieved, parental family living environment, political affiliations, family economic conditions, monthly consumption, history of travel to high-risk areas, underlying diseases, vaccine status of family members and side effects developed after receiving other vaccines.

-

3.

Attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine (11 items): influences of COVID-19, risk perception, vaccine acceptance and concerns about the vaccine. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale and the total score ranged from 11 to 55; a higher total score indicated a more positive attitude.

-

4.

Knowledge on the COVID-19 vaccine (9 items): (a) priority groups for vaccination, recommended age group for vaccination, correct methods, contraindications, adverse reactions, matters needing attention and herd immunity. This domain included single-choice and multiple-choice questions. Each correct answer to the single-choice questions obtained a score of 5, while each correct answer to the multiple-choice questions obtained a score of 1. The total score ranged from 1 to 46, with a higher total score indicating a better mastery of knowledge; and (b) The sources of acquired knowledge included mobile phone, TV, radio, network, newspaper, school/community pamphlet/bulletin board, relatives/friends and others.

-

5.

Vaccination willingness (8 items): vaccine selection, vaccination form, duration of protection, willingness, reasons and vaccine prices. Two of these items were scored to determine the level of vaccination willingness, with scores ranging from 1 to 8; a higher score indicated a stronger vaccination intention. The rest of the items were rated using percentages.

2.3. Sample and setting

This survey included 15 items related to the participants’ baseline information and 3 items related to the questionnaire dimensions, giving rise to 31 variables for statistical analysis. According to the Kendall sample estimation method for multivariate analysis, the required sample should be 10–20 times as high as the number of variables (Wang, 1990). In this regard, the minimum sample size of this survey was 310–620. College students, those majoring in nursing and those provided informed consent were included in the study. By contrast, part-time students were excluded. A total of 1488 nursing students participated in this study.

We initially contacted the deans of the nursing schools of the two universities and called the counselors (full-time faculty members who are responsible for managing the students’ daily lives and studies in China) after the deans agreed. We explained the purpose, content and matters needing attention of this study to the counselors. The counselors convened all nursing students to receive an explanation of this survey; the students participated in the study after providing an informed consent. WeChat groups were set up according to grade levels; students who volunteered to participate in this study were provided grade relevant QR codes, which were scanned to log in to their respective WeChat groups. WeChat is a widely used social application with more than 1 billion users in China. We uploaded the questionnaire to Wenjuanxing (https://www.wjx.cn), which is a commonly used online survey website in China. After uploading, a QR code poster was generated, and the researcher emailed the QR code poster to the counselors. They then uploaded the poster to the different survey WeChat groups and the students scanned the code to access the Wenjuanxing website and fill out the questionnaire.

2.4. Ethics aspects

The study was approved by the Human Subjects Ethics Sub-Committee of Shandong First Medical University (registration number: R202105170156). All participants agreed to participate in the study. The questionnaire was filled in anonymously and the data were kept confidential and used for research purposes only.

2.5. Data analysis

The SPSS software (version 19.0; SPSS Inc.) was used for statistical analysis. Students’ demographic and information-sourcing characteristics were expressed as means with standard deviations and frequencies with percentages. The item scoring ratio was calculated by dividing the actual score with the total score of each item and then multiplying by 100%. The data distribution was presented using a histogram and a Q-Q plot. Independent sample t-tests/one-way analysis of variance (normal distribution) and Mann-Whitney U tests/Kruskal-Wallis H tests (skewness distribution) were carried out to distinguish the differences in the sociodemographic characteristics between participants. The relationships among AKW were examined using Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis. Multiple linear regression was used to explore the factors influencing the AKW. A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant (two tailed).

2.6. Validity and reliability

Four experts were invited to review the questionnaire, including two professors in public health, a community-based nursing specialist in charge of vaccination and a nursing education specialist. All the experts had more than 15 years of professional experience and senior professional titles. The content validity index of the questionnaire was 0.98. Prior to the survey, a convenience sampling method was used to select 20 nursing students who met the sampling criteria for a presurvey to clarify the acceptability of the questionnaire. The respondents found the questionnaire items clear and easy to understand. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for KAP scales was 0.715.

3. Results

A total of 1512 copies of the questionnaire were received. Those with incomplete baseline data and those with identical scores for all items were excluded; hence, only 1488 valid copies with an effectivity rate of 98.41% were included in the final analysis.

3.1. Characteristics of nursing students

The demographic data of the study population that accounted for most were as follows: female gender (84.27%), age between 21 and 22 years (23.99%), Han Chinese (98.52%), class of 2020 (42.14%), with bachelor’s degree (82.93), with a science background in high school (60.15%), with a parental family living in a new community (30.98%), League members (82.93%), whose family belong to the middle class (78.49%), had a monthly expenses of 800–1500 RMB (71.51%), had no history of travel to areas above medium risk in the past 6 months (99.26%), had no underlying diseases (97.98%), had no family members who received the COVID-19 vaccine (59.34%) and whose family members did not experience side effects after receiving other vaccines (98.45%). ( Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics, univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with nursing students’ attitudes, knowledge, and willingness of COVID-19 vaccine (N = 1488).

|

Attitudes |

Knowledge |

Willingness |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Content | N (%) | M ± SD | t/F | p | β | P50 (P25, P75) | Scoring rate | Z/H | p | β | M ± SD | t/F | p | β |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 234 (15.73) | 38.31 ± 5.07 | -0.77 | 0.44 | 35(27, 40) | 71.91% | -8.39 | < 0.001 | 0.22** | 6.52 ± 1.28 | -3.02 | 0.003 | 0.07** | ||

| Female | 1254 (84.27) | 38.59 ± 4.35 | 40(36, 42) | 82.35% | 6.79 ± 1.02 | ||||||||||

| Age(years) | |||||||||||||||

| <18 | 5 (0.34) | 38.80 ± 3.70 | 2.15 | 0.045 | 42(26, 42) | 77.83% | 38.29 | < 0.001 | 6.80 ± 1.10 | 1.94 | 0.07 | ||||

| 18~ | 163 (10.95) | 38.49 ± 4.85 | 38(31, 41) | 76.13% | 6.53 ± 1.27 | ||||||||||

| 19~ | 326 (21.91) | 38.18 ± 4.31 | 39(33, 41) | 79.00% | 6.74 ± 1.05 | ||||||||||

| 20~ | 293 (19.69) | 39.03 ± 4.49 | 39(35, 41) | 79.26% | 6.87 ± 1.08 | ||||||||||

| 21~ | 357 (23.99) | 38.08 ± 4.50 | 40(36, 42) | 82.46% | 6.75 ± 1.01 | ||||||||||

| 22~ | 241 (16.20) | 39.06 ± 4.46 | 40(37, 42) | 83.72% | 6.71 ± 1.06 | ||||||||||

| 23~ | 103 (6.92) | 38.74 ± 4.16 | 40(37, 42) | 84.35% | 6.85 ± 0.90 | ||||||||||

| Nationality | |||||||||||||||

| Han | 1466 (98.52) | 38.53 ± 4.49 | -0.87 | 0.39 | 39(35, 42) | 80.67% | -0.45 | 0.65 | 6.75 ± 1.06 | 0.49 | 0.63 | ||||

| Others | 22 (1.48) | 39.36 ± 3.46 | 38.5(36.5, 42) | 82.91% | 6.64 ± 1.29 | ||||||||||

| Grade | |||||||||||||||

| Class of 2017 | 172 (11.56) | 39.34 ± 4.65 | 4.81 | 0.002 | 40(38, 42) | 84.52% | 39.03 | < 0.001 | -0.08** | 6.58 ± 0.90 | 5.18 | 0.001 | |||

| Class of 2018 | 434 (29.17) | 38.22 ± 4.58 | 40(36, 42) | 81.87% | 6.76 ± 1.04 | ||||||||||

| Class of 2019 | 255 (17.14) | 39.15 ± 4.24 | 40(36, 42) | 82.09% | 6.95 ± 0.97 | ||||||||||

| Class of 2020 | 627 (42.14) | 38.30 ± 4.40 | 38 (33, 41) | 78.26% | 6.70 ± 1.15 | ||||||||||

| Educational level | |||||||||||||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 1234 (82.93) | 38.59 ± 4.47 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 39(35, 42) | 80.11% | 8.30 | 0.02 | 6.73 ± 1.10 | 4.64 | 0.01 | ||||

| College-undergraduate student | 146 (9.81) | 38.23 ± 4.05 | 40(37, 42) | 84.22% | 6.99 ± 0.94 | ||||||||||

| College degree | 108 (7.26) | 38.42 ± 5.02 | 40(36, 42) | 82.70% | 6.62 ± 0.77 | ||||||||||

| Academic background in high school | |||||||||||||||

| Liberal arts | 593 (39.85) | 38.87 ± 4.39 | 2.30 | 0.02 | 40(37, 42) | 83.24% | -6.71 | < 0.001 | -0.11** | 6.88 ± 0.97 | 4.19 | < 0.001 | -0.09** | ||

| Science | 895 (60.15) | 38.33 ± 4.52 | 39(34, 41) | 79.02% | 6.65 ± 1.12 | ||||||||||

| Parental family living environment | |||||||||||||||

| New community | 461 (30.98) | 38.89 ± 4.52 | 1.97 | 0.10 | 40(35, 42) | 80.54% | 1.84 | 0.77 | 6.75 ± 1.14 | 1.05 | 0.38 | ||||

| Old community over 30 years | 107 (7.19) | 37.71 ± 4.22 | 40(35, 42) | 80.26% | 6.69 ± 1.09 | ||||||||||

| Village in the city | 93 (6.25) | 38.76 ± 4.44 | 38(34, 41) | 79.15% | 6.92 ± 0.97 | ||||||||||

| Public rental housing | 8 (0.54) | 37.25 ± 6.76 | 38.5(25.5,41.5) | 74.74% | 7.13 ± 0.64 | ||||||||||

| Rural area | 819 (55.04) | 38.44 ± 4.45 | 39(35, 42) | 81.09% | 6.73 ± 1.03 | ||||||||||

| Politics affiliationsa | |||||||||||||||

| Party members | 94 (6.32) | 38.40 ± 4.81 | 1.13 | 0.32 | 40(36.75, 41) | 82.63% | 8.91 | 0.01 | 6.61 ± 1.01 | 1.05 | 0.35 | ||||

| League members | 1234 (82.93) | 38.62 ± 4.44 | 39(35, 42) | 81.07% | 6.76 ± 1.07 | ||||||||||

| The masses | 160 (10.75) | 38.06 ± 4.52 | 38(31, 41) | 76.70% | 6.71 ± 1.10 | ||||||||||

| Family economic conditions | |||||||||||||||

| Good | 47 (3.16) | 39.28 ± 5.26 | 2.67 | 0.07 | 39(33, 42) | 79.37% | 0.10 | 0.95 | 6.74 ± 0.94 | 0.55 | 0.58 | ||||

| Medium | 1168 (78.49) | 38.40 ± 4.44 | 39(35, 42) | 80.80% | 6.76 ± 1.07 | ||||||||||

| Low | 273 (18.35) | 39.01 ± 4.47 | 39(35, 41) | 80.52% | 6.68 ± 1.08 | ||||||||||

| Monthly consumption (RMB)b | |||||||||||||||

| <800 | 194 (13.04) | 38.47 ± 4.53 | 0.91 | 0.46 | 39(34, 41) | 79.15% | 9.44 | 0.051 | 6.59 ± 1.08 | 3.54 | 0.007 | ||||

| 800–1500 | 1064 (71.51) | 38.52 ± 4.39 | 39(35, 42) | 81.20% | 6.81 ± 1.02 | ||||||||||

| 1500–2500 | 213 (14.31) | 38.81 ± 4.71 | 39(35, 42) | 80.63% | 6.58 ± 1.24 | ||||||||||

| 2500–3500 | 12 (0.81) | 38.42 ± 6.08 | 34(20.75,39.5) | 66.13% | 6.92 ± 1.31 | ||||||||||

| >3500 | 5 (0.34) | 35.20 ± 6.46 | 34(28, 39.5) | 73.48% | 6.40 ± 1.14 | ||||||||||

| Traveling to above medium risk areas in the past six months | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 11 (0.74) | Yes | -0.13 | 0.89 | 36(28, 39) | 72.72% | -1.83 | 0.07 | 5.64 ± 1.80 | -8.48 | 0.001 | -0.07** | |||

| No | 1477 (99.26) | No | 39(35, 42) | 80.76% | 6.75 ± 1.06 | ||||||||||

| Underlying diseases | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 30 (2.02) | Yes | 0.24 | 0.81 | 40(35, 42) | 81.46% | -0.57 | 0.57 | 6.43 ± 1.14 | -1.62 | 0.11 | ||||

| No | 1458 (97.98) | No | 39(35, 42) | 80.67% | 6.75 ± 1.06 | ||||||||||

| Family members received the COVID-19 vaccine | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 605 (40.66) | 38.94 ± 4.45 | 2.81 | 0.005 | 0.07* | 40(36, 42) | 81.07% | -2.40 | 0.02 | 6.83 ± 0.98 | 2.52 | 0.012 | 0.06* | ||

| No | 883 (59.34) | 38.27 ± 4.48 | 39(35, 41) | 80.46% | 6.69 ± 1.12 | ||||||||||

| You and your family members had side effects after receiving other vaccines | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 23 (1.55) | 38.52 ± 4.59 | -0.02 | 0.98 | 37(29, 42) | 74.11% | -1.26 | 0.21 | 6.13 ± 1.49 | -2.80 | 0.005 | -0.07** | |||

| No | 1465 (98.45) | 38.54 ± 4.47 | 39(35, 42) | 80.80% | 6.76 ± 1.06 | ||||||||||

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

In China, political affiliations are divided into Party members, League members and the masses. In terms of political consciousness or political enthusiasm, Party members are the highest, League members are medium, and the masses are low.

Monthly consumption (RMB) refers to the basic monthly life expenses of a student.

3.2. Scoring

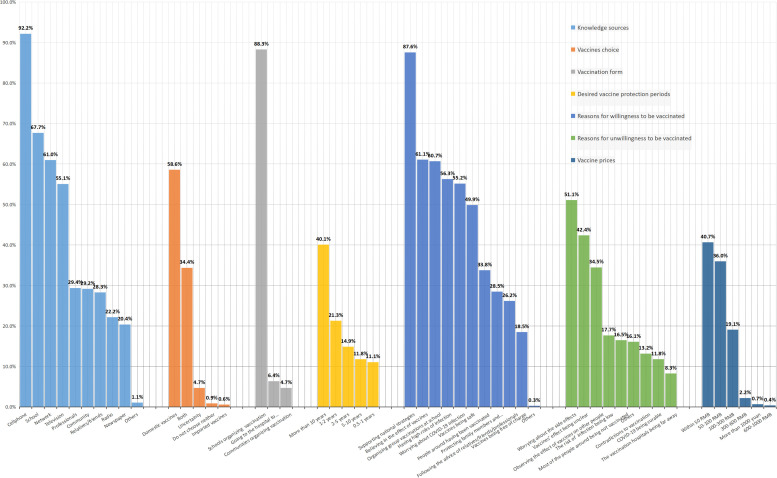

The attitude, willingness and questionnaire scores showed a normal distribution, while the knowledge scores showed a skewed distribution. The mean score of the attitude dimension was 38.54 ± 4.48 and the score rate was 70.07%. In this dimension, “Infection with COVID-19 has a high impact on the surrounding people or environment” (88.80%) garnered the highest score, while “Perceived high risk of infection with COVID-19″ garnered the lowest score (49.20%). The score rate in the knowledge dimension was 80.70%. In this dimension, “contraindications for the COVID-19 vaccine” (89.40%) had the highest score, while “correct method of vaccination” (63.75%) had the lowest score. The mean score of the willingness to be vaccinated was 6.75 ± 1.07 with a score rate of 84.38%. ( Table 2) The top three reasons for willingness to be vaccinated were as follows: supporting national strategies (87.57%), believing in the vaccine (61.09%) and organizing group vaccinations at school (60.69%). The top three reasons for unwillingness to be vaccinated were as follows: worrying about the side effects of the vaccine (51.14%), unclear understanding of its effects owing to recent introduction of the vaccine (42.41%) and observing the effect of vaccination on others (34.54%). In terms of vaccine selection, students were more willing to choose domestic vaccines (58.94%) and they hoped that schools will organize collective vaccination programs (88.78%). The desired vaccine protection period was more than 10 years (40.39%). Even with fees, 74.46% of students were willing to be vaccinated and the top three acceptable vaccine prices were less than 50 RMB (40.99%), 50–100 RMB (36.29%) and 100–300 RMB (19.22%). ( Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Scores of attitudes, knowledge and willingness of COVID-19 vaccine (N = 1488).

| Dimension | Item | Score range | Mean(SD) | P50 (P25, P75) |

Scoring rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 11–55 | 38.54 ± 4.48 | 70.07 | ||

| Do you think that contracting COVID-19 has a significant impact on your health? | 1–5 | 3.88 ± 1.17 | 77.60 | ||

| Do you think that it will affect the people around you or the environment if you get COVID-19? | 1–5 | 4.44 ± 0.84 | 88.80 | ||

| Do you think that the current pandemic is serious? | 1–5 | 3.18 ± 0.81 | 63.60 | ||

| Do you think that the pandemic will recur in China? | 1–5 | 3.21 ± 1.00 | 64.20 | ||

| How much has the pandemic affected your life in the past 6 months? | 1–5 | 3.54 ± 0.88 | 70.80 | ||

| How much is the pandemic will affect your life in the next 6 months? | 1–5 | 2.99 ± 0.81 | 59.80 | ||

| Do you think that you are at high risk of contracting COVID-19 ? | 1–5 | 2.46 ± 0.94 | 49.20 | ||

| Do you think you that you can get prevention from COVID-19 by vaccination? | 1–5 | 3.77 ± 0.62 | 75.40 | ||

| Do you think that the vaccines available on the market are safe? | 1–5 | 3.58 ± 0.66 | 71.60 | ||

| Do you think that the vaccine is effective? | 1–5 | 3.66 ± 0.62 | 73.20 | ||

| How much do you care about vaccine-related information? | 1–5 | 3.82 ± 0.79 | 76.40 | ||

| Knowledge | 1–46 | 39(35, 42) | 80.70 | ||

| Do you know who are the priority groups for vaccination? | 0–8 | 8(8,8) | 89.00 | ||

| What is the recommended age group for the vaccination? | 0/5 | 4(4, 4) | 79.60 | ||

| What are the correct methods of vaccination? | 0–8 | 5(4, 7) | 63.75 | ||

| What are the contraindications of the COVID-19 vaccine? | 0–5 | 5(5,5) | 89.40 | ||

| Which of the following statements are true? | 0–5 | 5(4,5) | 86.00 | ||

| Precautions for vaccination | 0–5 | 5(5,5) | 88.40 | ||

| How can herd immunity be achieved through vaccination? | 0/5 | 5(5, 5) | 87.00 | ||

| In general, how familiar are you with the COVID-19 vaccine? | 1–5 | 3(3, 4) | 67.60 | ||

| Vaccination willingness | 2–8 | 6.75 ± 1.07 | 84.38 | ||

| Do you want to be vaccinated against COVID-19? | 1–6 | 5.00 ± 0.85 | 83.33 | ||

| Would you be willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine if you are charged for it in the future? | 1–2 | 1.74 ± 0.44 | 87.00 | ||

| Total scale | 14–109 | 82.41 ± 8.50 | 75.61 |

Fig. 1.

Knowledge sources, vaccines choice, vaccination form, desired vaccine protection periods, reasons for willingness and unwillingness to be vaccinated, vaccine prices.

3.3. Influencing factors

The demographic characteristics of the participants were used as grouping variables. Based on the statistical results, when age, grade, academic background in high school and family members who had received the COVID-19 vaccine were used as grouping variables, the differences in mean scores of attitudes were significant and the scores of attitudes toward vaccines were significantly higher among high-grade students than among low-grade students (juniors vs. sophomores and freshmen: 39.34 vs. 39.15 and 38.30, p = 0.002). With regard to the knowledge dimension, significant differences were observed in the scores in terms of sex, age, grade, educational level, academic background, political affiliations and family members who received the COVID-19 vaccine. The knowledge scores of female students were higher than those of male students (e.g., female students vs. male students: 82.35% vs. 71.91%, p < 0.001), the knowledge mastery level increased significantly with age (e.g. 23~, 22~ and 21~ vs. 20~, 19~ and 18~: 84.35%, 83.72% and 82.46% vs. 79.26%, 79.00% and 76.13%, p < 0.001) and the knowledge mastery level of college-undergraduate students was significantly higher than that of undergraduates and college graduates (e.g., college-undergraduate students vs. undergraduate and college students: 84.22% vs. 80.11% and 82.70%, p = 0.02). With regard to vaccination willingness, significant differences were observed in scores in terms of sex, grade, educational level, academic background in high school, monthly expenses, history of travel to above medium-risk areas, family members who received the COVID-19 vaccine and had side effects after receiving other vaccines. The willingness to be vaccinated was much higher among sophomores and juniors than among freshmen and seniors (e.g., sophomores and juniors vs. freshmen and seniors: 6.95 and 6.76 vs. 6.70 and 6.58, p = 0.001). It was also higher among female students than among male students (e.g., female students vs. male students: 6.79 vs. 6.52, p < 0.001). Students whose family members received the COVID-19 vaccine scored higher than those whose family members did not receive the vaccine (e.g., yes vs no: 6.83 vs. 6.69).

Multiple linear regression analysis showed that vaccination status of family members was the significant factors that influenced the students’ attitude toward the COVID-19 vaccine. The main factors influencing knowledge were sex, grade and academic background. With regard to the willingness to be vaccinated, sex, academic background, visits to areas above medium risk in the past 6 months, family members’ vaccination status and the side effects experienced after receiving other vaccines were significant influencing factors (Table 1).

4. Discussion

This study developed the AKW questionnaire through literature review, group discussion and consultation with experts. The content validity of the scale was 0.98 and the Cronbach’s a coefficient was 0.71, indicating that the scale has some reliability. The AKW score in this study was 82.41 ± 8.50 (range: 14–109), indicating that nursing students had a positive perception of the COVID-19 vaccine and were willing to receive it.

4.1. Attitudes

The items in the attitude dimension that obtained a low score were “Do you think the current outbreak is serious?” (63.60%), “Do you think the outbreak will recur in China?” (64.20%), “How much is the outbreak expected to affect your life in the next 5 months?” (59.80%) and “Do you think you are at high risk of contracting COVID-19?” (49.20%). The related fact is that the pandemic is now better controlled in China, leading to students being less vigilant due to beliefs that the pandemic will not recur and that the chance of infection is small. This finding suggests that the acceptance of the vaccine was lower when the perceived severity and fear of COVID-19 were lower, which is in agreement with the existing literature (Qiao et al., 2020, Graffigna et al., 2020, Reiter et al., 2020). Kwok et al. (2021) found that the hospital nurses’ willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 declined after the COVID-19 pandemic situation improved. Therefore, schools should strengthen education regarding the COVID-19 vaccine and highlight the importance of vaccination among students, while accelerating the vaccination process with full respect for students’ vaccination willingness, to increase the vaccination rates. Although the risk of the pandemic is perceived as low, students also believe that once they are infected with COVID-19, it can have a significant impact on them personally and their environment.

A positive attitude is an important factor in controlling the outbreak and increases the willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine (Yang et al., 2021). In this study, students whose family members had been vaccinated were able to view the vaccine with a more positive attitude. Family members receiving the COVID-19 vaccine had a positive influence on vaccination attitudes (Dror et al., 2020, Bell et al., 2020). Students in the present study had moderate approval of the vaccine’s effectiveness and safety, which was in line with the reports of existing studies (Kreps et al., 2020). Univariate analysis revealed that the attitude scores of the senior students were significantly higher than those of students from other grades. As the senior students were in hospital internship, they would be exposed to various types of patients every day and thus their risk of contracting COVID-19 was much higher than the risk of students from other three grades. As a result, their attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine were more positive. Students with liberal arts backgrounds in this study scored higher on attitude. In China, nursing schools mainly recruit science students and liberal arts students usually accounted for a relatively small proportion. The COVID-19 pandemic had a greater psychological impact on liberal arts students than on science students and the liberal arts students were more likely to experience anxiety (Odriozola-González et al., 2020), leading to greater awareness and recognition of the vaccine (Reiter, Pennell and Katz et al., 2020).

4.2. Knowledge

The scoring rate of knowledge dimension was 80.70%. Item analysis showed that out of the 7 knowledge items, 5 items (contraindication of vaccination, key vaccinated groups, precautions after vaccination, herd immunity and adverse reactions) scored at more than 80%, indicating that most students had a good grasp of the COVID-19 vaccine. However, the relatively low scoring items of “the correct way to vaccinate (63.75%) and the recommended age group for the vaccination” (79.60%) suggested that these were weak points that needed to be strengthened. In the “correct method of vaccination” item, adenovirus vaccines and recombinant vaccine inoculation methods obtained the lowest scores. Only 40.39% of the students could clearly point out that nucleic acid testing was not necessary before vaccination, while most students believed that nucleic acid testing was necessary. Approximately 69.83% of the students believed that the age group suitable for vaccination was 18–60 years. However, according to the latest guidelines issued by the National Health Commission of China (2020), the recommended age for vaccination was changed to above 18 years, which suggested that the students’ knowledge should be updated over time.

In terms of vaccine information sources, mobile phones, school training, computers and televisions ranked the top. Mobile phones and computers were the devices that college students used daily, which were the primary sources of information. Interestingly, school training performed better than usage of computers in this study, which was not consistent with the reports of previous research (Olaimat et al., 2020). College students are an important group of individuals who can help promote the prevention of an epidemic. China is now vigorously carrying out the policy of universal immunization, which has attracted great attention from government departments, school management and teachers. Schools often hold lectures on COVID-19, emphasizing the importance of COVID-19 and integrating COVID-19-related knowledge into students’ daily lives, which improved students’ knowledge of COVID-19 vaccine. Grade, sex and high school background were significant predictors of knowledge. Older individuals and senior students had a greater capacity to acquire and absorb knowledge (Olaimat et al., 2020); their knowledge scores were significantly higher than those of younger individuals and junior students. Female students scored higher than male students, which was consistent with the results of previous research (Albaqawi et al., 2020, Zhong et al., 2020). Therefore, nursing educators should adopt a variety of education methods according to students’ characteristics to improve students’ knowledge of vaccines as well as to reduce their hesitation about vaccines.

4.3. Vaccination willingness

Among the 1488 students interviewed, the scoring rate of vaccination willingness was 5.00 ± 0.85 (83.33%), which was in the middle to upper level compared with that reported in existing studies (Qiao et al., 2020, Sun et al., 2020, Graupensperger et al., 2021, Di Giuseppe et al., 2021); this finding indicated that nursing students were more willing to be vaccinated than students in other majors. Results of the analysis of the reasons for willingness/unwillingness to be vaccinated showed that nursing students could have a certain degree of understanding of the necessity, effectiveness and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine based on their professional foundation. Moreover, their schools are preparing to organize group vaccinations, to increase the students’ vaccination willingness. What cannot be ignored is that students still have uncertainties about the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines. If this reluctance is not addressed prior to vaccination, it may reduce the actual number of vaccinated students and cause psychological pressure as well as unnecessary distress after vaccination (Lucia et al., 2020, Qiao et al., 2020).

According to the results of the regression analysis, sex, academic background, visits to areas above medium risk in the last 6 months, vaccination status of family members and side effects experienced after vaccination were significant factors influencing the vaccination willingness. In this study, the vaccination willingness of female students was significantly higher than that of male students, which is inconsistent with the results of existing studies (Freeman et al., 2020, Unroe et al., 2021). This could be due to the fact that nursing is traditionally a female-dominated profession and male students who are a minority group in nursing schools sometimes feel isolated and are reluctant to participate in group activities (Powers et al., 2018), which may lead to a decrease in vaccination willingness (Christensen et al., 2018). Therefore, nursing educators should think about putting themselves in the shoes of different types of students and paying attention to the small but important group of male students during vaccination.

In this study, the vaccination rate of family members of the surveyed students was 40.66% (605/1488) and the incidence of adverse reactions was 6.12% (37/605), which was higher than the median incidence of adverse reactions reported in existing studies (0.1–15.8%) (Baden et al., 2021; China NHC, 2021). Therefore, students might not show willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. In view of this, schools should strengthen education on the adverse reactions of COVID-19 vaccine; it should not only include the provision of theoretical knowledge, but also discuss the actual psychological and physiological effects of the vaccine, so that students can have an objective understanding of the side effects of vaccine, thus eliminating fear and enhancing the willingness to be vaccinated. Regarding vaccine selection, most students were willing to receive the vaccine even with a fee, with the acceptable price being within 100 RMB. Most of the students in this study spend 800–1500 RMB per month. Thus, a vaccine price within 100 RMB is affordable for students. This also provides a reference for policy makers when setting vaccine prices, with recommendations that the vaccine prices be reasonable by basing it on the premise of ensuring medical equity.

4.4. Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. First, to ensure the timeliness of the survey, we conducted an initial validation of the survey instrument through expert review. Although the CVI coefficient and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient are acceptable, further standard validation measures are needed. Second, this study was conducted 3 months after the vaccine was released, which may only reflect the initial stage of willingness to be vaccinated. Further research is still needed to analyze the middle and later stages of willingness to be vaccinated as well as the actual vaccination behavior.

5. Conclusion

The study explored the nursing students’ attitudes, knowledge and vaccination willingness as well as the related factors. The nursing students were not only representative of the medical professionals, but also representative of college students. This study served as a reference for policy makers to understand the vaccination willingness of medical workers and young people, which could optimize the management strategy of COVID-19 vaccination. The findings of this study can also help nursing educators to enhance follow-up education and increase the vaccination rates, with a focus on male students, lower age groups, those with science backgrounds and lower grades, students whose family members have not received the COVID-19 vaccine and those whose family members experienced side effects after receiving other vaccines. Due to the limitations posed by the study’s sample, further expansion of the study population to include post-secondary and specialist nursing students is needed to support our findings. In addition, further studies related to students’ anonymous vaccination intentions and actual vaccination behaviors are needed to evaluate the practical significance of this survey.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ning Jiang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft. Baojian Wei: Software, Investigation. Hua Lin: Investigation, Resources. Youjuan Wang : Data Curation, Resources. Shouxia Chai: Resources, Writing – Review & Editing. Wei Liu: Supervision, Project administration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all nursing students and their counselors in this study for their contributions.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103148.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

References

- Albaqawi H.M., Alquwez N., Balay-Odao E., Bajet J.B., Alabdulaziz H., Alsolami F., Tumala R.B., Alsharari A.F., Tork H., Felemban E.M., Cruz J.P. Nursing students’ perceptions, knowledge and preventive behaviors toward COVID-19: a multi-university study. Front. Public Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.573390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., Diemert D., Spector S.A., Rouphael N., Creech C.B., McGettigan J., Khetan S., Segall N., Solis J., Brosz A., Fierro C., Schwartz H., Neuzil K., Corey L., Gilbert P., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384(5):403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S., Clarke R., Mounier-Jack S., Walker J.L., Paterson P. Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study in England. Vaccine. 2020;38(49):7789–7798. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention [China CDC], 2021. Vaccines for COVID-19. Retrieved from 〈https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/index.html〉.

- Christensen M., Welch A., Barr J. Men are from Mars: the challenges of communicating as a male nursing student. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2018;33:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe G., Pelullo C.P., Della Polla G., Pavia M., Angelillo I.F. Exploring the willingness to accept SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in a university population in Southern Italy, september to november 2020. Vaccines. 2021;9(3):275. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dror A.A., Eisenbach N., Taiber S., Morozov N.G., Mizrachi M., Zigron A., Srouji S., Sela E. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):775–779. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Loe B.S., Chadwick A., Vaccari C., Waite F., Rosebrock L., Jenner L., Petit A., Lewandowsky S., Vanderslott S., Innocenti S., Larkin M., Giubilini A., Yu L.M., McShane H., Pollard A.J., Lambe S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol. Med. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J., Reynolds M., Barnby E. An informative discussion for school nurses on COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. NASN Sch. Nurse. 2021;36(3):132–136. doi: 10.1177/1942602×21999606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graupensperger S., Abdallah D.A., Lee C.M. Social norms and vaccine uptake: college students’ COVID vaccination intentions, attitudes and estimated peer norms and comparisons with influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2021;39(15):2060–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graffigna, G., Palamenghi, L., Boccia, S., Barello, S., 2020. Relationship between citizens’ health engagement and intention to take the covid-19 vaccine in italy: A mediation analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kreps S., Prasad S., Brownstein J.S., Hswen Y., Garibaldi B.T., Zhang B., Kriner D.L. Factors associated With US adults’ likelihood of accepting COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukreti S., Lu M.Y., Lin Y.H., Strong C., Lin C.Y., Ko N.Y., Chen P.L., Ko W.C. Willingness of Taiwan’s healthcare workers and outpatients to vaccinate against COVID-19 during a period without community outbreaks. Vaccines. 2021;9(3):246. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok K.O., Li K.K., Wei W.I., Tang A., Wong S., Lee S.S. Editor’s Choice: influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: a survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021;114 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Hu Z., Zhao Q., Alias H., Danaee M., Wong L.P. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: a nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucia V.C., Kelekar A., Afonso N.M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J. Public Health. 2020:fdaa230. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M.L., Gerolamo A.M., Marino M.A., Hanson-Zalot M.E., Pogorzelska-Maziarz M. COVID-19 vaccination readiness among nurse faculty and student nurses. Nurs. Outlook. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.01.019. S0029-6554(21)00023-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic China [China NHC], 2021. Incidence of adverse reactions to COVID-19 vaccine in China. Retrieved from 〈https://www.sohu.com/na/441626009_115362〉.

- National Health Commissionof the People’s Republic China [China NHC], 2021b. Technical Guidelines forCOVID-19 Vaccination (1st Edition). Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/29/content_5596577.htm.

- Odriozola-González P., Planchuelo-Gómez Á., Irurtia M.J., de Luis-García R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaimat A.N., Aolymat I., Shahbaz H.M., Holley R.A. Knowledge and information sources about COVID-19 among university students in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:254. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K., Cartmill R., Johnson-Gordon B., Landes M., Malik K., Sinnott J., Wallace K., Wallin R. Preparing for a school-located COVID-19 vaccination clinic. NASN Sch. Nurse. 2021;36(3):156–163. doi: 10.1177/1942602×21991643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers K., Herron E.K., Sheeler C., Sain A. The lived experience of being a male nursing student: implications for student retention and success. J. Prof. Nurs. 2018;34(6):475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao S., Tam C.C., Li X. Risk exposures, risk perceptions, negative attitudes toward general vaccination and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among college students in South Carolina. medRxiv Prepr. Serv. Health Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.11.26.20239483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter P.L., Pennell M.L., Katz M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 2020;38(42):6500–6507. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J., Stewart T., anderson K.B., Hanley S., Thomas S.J., Salmon D.A., Morley C. Assessment of US healthcare personnel attitudes towards coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in a large university healthcare system. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021:ciab054. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S., Lin D., Operario D. Interest in COVID-19 vaccine trials participation among young adults in China: willingness, reasons for hesitancy and demographic and psychosocial determinants. medRxiv Prepr. Serv. Health Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.13.20152678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szmyd B., Karuga F.F., Bartoszek A., Staniecka K., Siwecka N., Bartoszek A., Błaszczyk M., Radek M. Attitude and behaviors towards SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study from Poland. Vaccines. 2021;9(3):218. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The New York State Department of Health, 2021. Distribution of the Vaccine. Retrieved from 〈https://covid19vaccine.health.ny.gov/distribution-vaccine〉.

- Unroe K.T., Evans R., Weaver L., Rusyniak D., Blackburn J. Willingness of long-term care staff to receive a COVID-19 vaccine: a single state survey. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021;69(3):593–599. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 2021. COVID-19 Vaccines. Retrieved from 〈https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines#news〉.

- Wang J. Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers; 1990. Clinical Epidemiology-Design, Measurement and Evaluation of Clinical Scientific Research. [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2021a. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Retrieved from 〈https://covid19.who.int/〉.

- WHO, 2021b. Vaccine Explained' series features illustrated articles on vaccine development and distribution. Retrieved from 〈https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines/explainers〉.

- Yang K., Liu H., Ma L., Wang S., Tian Y., Zhang F., Li Z., Song Y., Jiang X. Knowledge, attitude and practice of residents in the prevention and control of COVID-19: an online questionnaire survey. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021;77(4):1839–1855. doi: 10.1111/jan.14718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoda T., Katsuyama H. Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination in Japan. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):48. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurttas B., Poyraz B.C., Sut N., Ozdede A., Oztas M., Uğurlu S., Tabak F., Hamuryudan V., Seyahi E. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine among patients with rheumatic diseases, healthcare workers and general population in Turkey: a web-based survey. Rheumatol. Int. 2021;41(6):1105–1114. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04841-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong B.L., Luo W., Li H.M., Zhang Q.Q., Liu X.G., Li W.T., Li Y. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16(10):1745–1752. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material