Abstract

The dried root of Isatis tinctoria L. (Brassicaceae) is one of the most popular traditional Chinese medicines with well-recognized prevention and treatment effects against viral infections. Above 300 components have been isolated from this herb, but their spatial distribution in the root tissue remains unknown. In recent years, mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) has become a booming technology for capturing the spatial accumulation and localization of molecules in fresh plants, animal, or human tissues. However, few studies were conducted on the dried herbal materials due to the obstacles in cryosectioning. In this study, distribution of phytochemicals in the dried root of Isatis tinctoria was revealed by microscopic mass spectrometry imaging, with application of atmospheric pressure–matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (AP-MALDI) and ion trap–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (IT-TOF/MS). After optimization of the slice preparation and matrix application, 118 ions were identified without extraction and isolation, and the locations of some metabolites in the dried root of Isatis tinctoria were comprehensively visualized for the first time. Combining with partial least square (PLS) regression, samples collected from four habitats were differentiated unambiguously based on their mass spectrometry imaging.

Keywords: mass spectrometry imaging, Isatis tinctoria, atmospheric pressure–matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization, ion trap–time-of-flight mass spectrometry, traditional Chinese medicine

Introduction

Natural products have always benefited the health care of people worldwide and are used as herbal medicines commonly (He et al., 2020). Among them, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has made significant contributions to the treatment of human disease from ancient times to present (Wang et al., 2021). For instance, the dried root of Isatis tinctoria L. (Isatis indigotica Fortune ex Lindl.) (Isatidis Radix in Latin, Isatis root in English, and Banlangen in Chinese) has been widely used as the remedy for fever and infection in China and other countries (Zhou and Zhang, 2013). It is well recognized for prevention and treatment effects against a variety of viral infections, such as seasonal flu (Speranza et al., 2020), severe acute respiratory syndrome (Lin et al., 2005), and H1N1 flu epidemic (Li and Tao, 2013; Luo et al., 2019). As the important ingredient in the so-called Three Drugs and Three Prescriptions, the dried root of Isatis tinctoria has also been playing an active role in fighting against the novel corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (Li et al., 2020b; Li and Xu, 2021). Till now, more than 300 components have been isolated from the root of Isatis indigotica, including alkaloids, sulfur-containing compounds, phenylpropanoids, amino acids, nucleosides, organic acids and esters, flavonoids, quinones, terpenes, sterols, saccharides, aromatics, peptides, alcohols, aldehydes and ketones, nitriles, and sphingolipids. Although chemical composition and pharmacological activities of phytochemicals in the dried root of Isatis tinctoria have been extensively investigated by Lin et al. (2005); Speranza et al. (2020), the analysis of their spatial distribution in tissue has not yet been done.

Unraveling the tissue-specific localization of molecules in medicinal herbs can provide straightforward clues to understand their biological functions. Technologies for this aim face challenges and are still under development. Conventional investigations have enabled the comprehensive chemical profiling of metabolites from the dried root of Isatis tinctoria, applying separation and identification techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Zou et al., 2005), ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) (Shi et al., 2012), and ultra-performance liquid chromatography–quadrupole–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF/MS) (Guo et al., 2020a). However, the microscopic localizations of components in samples are largely ignored during the homogenization and purification process.

By directly detecting the ion beams of components on a sample surface, mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) can achieve the chemical distribution information. With the aid of the optical microscope, MSI can link morphological features with chemical profiling, thus providing untargeted, label-free, and multiplexed approach for molecular imaging. In recent years, it has become a fascinating tool for capturing the spatial accumulation and localization of metabolites in plants (Shimma and Sagawa, 2019; Li et al., 2020a; Li et al., 2020c), but only a few studies had been conducted on the dried herbal materials (Ng et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007; Yi et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2014a; Liang et al., 2014b), which are extremely difficult to sectioning.

In the present study, distribution of phytochemicals in the dried root of Isatis tinctoria was revealed by microscopic mass spectrometry imaging, using atmospheric pressure–matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (AP-MALDI) combined with ion trap–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (IT-TOF/MS). In particular, the slice preparation method directly associated with the quality of the mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) results was optimized for the dried woody sample. Numerous constituents, including alkaloids, sulfur-containing compounds, phenylpropanoids, amino acids, nucleosides, organic acids, flavonoids, terpenes, saccharides, aromatics, peptides, and sphingolipids, were comprehensively visualized in the dried root of Isatis tinctoria for the first time. Moreover, samples from different habitats were distinguished based on their mass spectrometry imaging and the partial least square (PLS) regression.

Material and Methods

Chemicals and Samples

2′, 5′-Dihydroxyacetophenone (2, 5-DHAP), 2, 5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB), α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA), 1, 5-naphthalenediamine (1, 5-DAN), 9-aminoacridine (9-AA), 1, 8-bis(tetramethylguanidino)naphthalene (TMGN), 1, 2-bis (trimethoxysilyl)ethane (BTME), gelatin, formic acid (LC-MS grade), ethanol (HPLC grade), and methanol (LC-MS grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, United States ). De-ionized water was purified by a Milli-Q system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, United States). Optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound was purchased from Leica (Nussloch, Germany). The samples of the dried root of Isatis tinctoria were collected from four main habitats in China, Gansu, Heilongjiang, Xinjiang, and Neimenggu. The sample collection information could be found in Table 1, and the typical macroscopic images of the herb and its transverse section are shown in Figure 1. All samples were authenticated by Associate Professor Shuai Kang, who is in charge of the Traditional Chinese Medicine Herbarium, National Institutes for Food and Drug Control. The voucher specimens were deposited in National Institutes for Food and Drug Control (NIFDC), Beijing, China.

TABLE 1.

Sample collection information of the dried root of Isatis indigotica.

| Sample no | Habitat | Collection time |

|---|---|---|

| GS1 | Gansu | Sep., 2019 |

| GS2 | Gansu | Sep., 2019 |

| GS3 | Gansu | Sep., 2019 |

| HLJ1 | Heilongjiang | Oct., 2019 |

| HLJ2 | Heilongjiang | Oct., 2019 |

| HLJ3 | Heilongjiang | Nov., 2019 |

| XJ1 | Xinjiang | Sep., 2019 |

| XJ2 | Xinjiang | Oct., 2019 |

| XJ3 | Xinjiang | Oct., 2019 |

| NMG1 | Neimengu | Nov., 2019 |

| NMG2 | Neimengu | Oct., 2019 |

| NMG3 | Neimengu | Oct., 2019 |

FIGURE 1.

A photograph of the dried root of Isatis indigotica (A) and the magnified image of its transverse section (B).

Slice Preparation and Optical Imaging

A piece 1 cm in length was cut from the dried root of Isatis tinctoria using a blade, and then embedded in 0.1 g/ml gelatin solution before freezing at −20°C. The frozen sample embedded with gelatin was axially fixed on a cryomicrotome (Leica CM 1950, Nussloch, Germany) by OCT compound carefully to avoid contamination on the surface of the sample. The gelatin on the top was peeled off to expose the surface of the cross section of the root before one side of the double-sided conductive tape (3M, St. Paul, MN, United States) was adhered to the root surface. Then the tissue was sectioned into a 40-μm slice with the tape at −18°C. Finally, the slice was fixed carefully on an indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated glass slide (Matsunami Glass, Osaka, Japan) with another side of the tape. Before matrix coating, the optical image of the tissue was captured by a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera of the optical microscope embedded to the imaging mass microscope system (Shimadzu iMScope, Kyoto, Japan).

Matrix Application

After optimization, 2′, 5′-dihydroxyacetophenone (2, 5-DHAP) and 1, 5-naphthalenediamine (1, 5-DAN) were chosen as the matrix for positive and negative ion detection, respectively, and were applied in the mode of spraying. The matrix solution of 2′, 5′-dihydroxyacetophenone (2, 5-DHAP) was prepared at a concentration of 10 mg/ml in methanol and water (all containing 0.1% formic acid) at a ratio of 8:2, and 1, 5-naphthalenediamine (1, 5-DAN) was prepared as a saturated solution in ethanol–water (70:30). For spraying, 1 ml of matrix solution was added to the cavity of the handle airbrush. Then the solution was sprayed on the sample surface using the airbrush, keeping a distance at about 10 cm. For each glass, the airbrushing was repeated 10 cycles every 60 s. Finally, the sprayed glass slide was kept in the fume hood for 5 min to vaporize the solvent.

Microscopic Mass Spectrometry Imaging

Microscopic mass spectrometry imaging of the tissue was performed using the iMScope instrument (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an optical microscope, an atmospheric pressure chamber for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (AP-MALDI) source, and an ion trap–time-of-flight mass spectrometer. The acquisition region was defined with the help of the optical microscope, and the tissue was irradiated with a diode-pumped 355 nm Nd:YAG laser with 5 ns pulse width. The laser diameter was 80 μm, and the data were collected at an interval of 80 μm. The tissue surface was laser-irradiated with 100 shots (1,000 Hz repetition rate) for each pixel. All the data were acquired in the positive and negative modes with sample voltage of 3.5 and 3.0 kV, respectively. The mass ranges were m/z 100–500 and m/z 500–1,000, while the detector voltage was 1.97 kV for all the samples. Three repetitions for each sample were performed, and two slices were prepared for each repetition in order to measure the positive and negative ions separately.

Data Analysis

Mass image reconstruction and data analysis were performed using IMAGEREVEAL™ MS (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). All images were reconstructed by linear smoothing and displayed in absolute intensity after total ion current (TIC) normalization. Statistical analysis including principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares (PLS) regression was carried out by IMAGEREVEAL™ MS for differentiation of samples from different habitats.

Results

Phytochemical Profiles of the Dried Root of Isatis tinctoria

Figure 2 showed the typical overall average mass spectra of the dried root of Isatis tinctoria gained by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization and ion trap–time-of-flight (MALDI-IT-TOF) mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) under positive and negative/ionization modes. Positive ions were mainly detected in the mass range of m/z 100–400 and m/z 400–800, while negative ions were mainly observed in the mass range of m/z 100–200, m/z 400–500, and m/z 400–700. The putative identification of the components was based on the accurate mass-to-charge ratio with reference to the isotopic peak, the reference standards, and/or the literatures and data bases. As could be seen from Table 2, the detected phytochemicals belong to a wide range of chemical compound classes such as alkaloids, sulfur-containing compounds, phenylpropanoids, amino acids, nucleosides, organic acids, flavonoids, terpenes, saccharides, aromatics, peptides, and sphingolipids. In the positive ion mode, the detected ions were prominently in the protonated adduct form of all amino acids, most of the alkaloids, some of the phenylpropanoids and the nucleosides, majority of the aromatics, minority of the sulfur-containing compounds, several sphingolipids, as well as organic acids with basic group. Also sodium or potassium adducts of some nucleosides and a few alkaloids, peptides, and sulfur-containing compounds were found. In the negative ion mode, majority of the sulfur-containing compounds and the organic acids, some of the phenylpropanoids, minority of the aromatics, a few saccharides, flavonoids, nucleosides, as well as alkaloids with acid group were readily detected as [M−H]− form of ions.

FIGURE 2.

Typical overall average mass spectra acquired from a cross section of the dried root of Isatis indigotica by matrix-assisted laser desorption and ion trap–time-of-flight (MALDI-IT-TOF) mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) in the spectral ranges of m/z 100–500 in a positive mode (A), m/z 500–1,000 in a positive mode (B), m/z 100–500 in a negative mode (C), and m/z 500–1,000 in a negative mode (D).

TABLE 2.

Assignment of ions observed in the matrix-assisted laser desorption and ion trap–time-of-flight (MALDI-IT-TOF) mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) of the dried root of Isatis indigotica with references regarding shown compounds.

| No | Compound | Chemical class | Ion formula | Theoretical m/z | Observed m/z | Mass accuracy (ppm) | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | r-Aminobutyric acid | Amino acids | C4H9NO2+H | 104.0712 | 104.0709 | 2.9 | Pan, (2014) |

| 2 | Choline | Alkaloids | C5H14NO+ | 104.1075 | 104.1066 | 8.6 | The Metabolomics Innovation Center, (2020) |

| 3 | Proline | Amino acids | C5H9NO2+H | 116.0712 | 116.0709 | 2.6 | Wu et al. (1997) |

| 4 | Valine | Amino acids | C5H11NO2+H | 118.0869 | 118.0865 | 3.4 | Chen et al. (2012) |

| 5 | Leucine/isoleucine | Amino acids | C6H13NO2+H | 132.1025 | 132.1018 | 5.3 | Zhao, (2015) |

| 6 | Adenine | Nucleosides | C5H5N5+H | 136.0624 | 136.0613 | 8.1 | Chen et al. (2012) |

| 7 | Aminobenzoic acid | Organic acids | C7H7NO2+H | 138.0556 | 138.0545 | 8.0 | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 8 | 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl) phenol | Aromatics | C8H10O2+H | 139.0760 | 139.0773 | 9.3 | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 9 | Hexyl isothiocyanate | Alkaloids | C7H13NS + H | 144.0848 | 144.0853 | 3.5 | Condurso et al. (2006) |

| 10 | 3-Formylindole | Alkaloids | C9H7NO + H | 146.0607 | 146.0614 | 4.8 | Zhao, (2015) |

| 11 | Glutamine | Alkaloids | C5H10N2O3+H | 147.0770 | 147.0758 | 8.2 | Pan, (2014) |

| 12 | Lysine | Amino acids | C6H14N2O2+H | 147.1154 | 147.1132 | 1.4 | Pan, (2014) |

| 13 | Uracil | Nucleosides | C4H4N2O2+K | 151.1256 | 151.1243 | 8.6 | Pan et al. (2013) |

| 14 | Guanine | Nucleosides | C5H5N5O + H | 152.0573 | 152.0588 | 9.9 | Pan et al. (2013) |

| 15 | Dopamine | Alkaloids | C8H11NO2+H | 154.0791 | 154.0790 | 0.6 | HighChem LLC, (2020) |

| 16 | Oxindole | Alkaloids | C8H7NO + Na | 156.0426 | 156.0416 | 6.4 | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 17 | Histidine | Amino acids | C6H9N3O2+H | 156.0774 | 156.0786 | 7.7 | Pan, (2014) |

| 18 | Hypoxanthine | Nucleosides | C5H4N4O + Na | 159.0283 | 159.0275 | 5.0 | Xiao et al. (2003) |

| 19 | 3-Indoleformic acid | Alkaloids | C9H7NO2+H | 162.0556 | 162.0553 | 1.9 | Yang et al. (2014b) |

| 20 | Phenylalanine | Amino acids | C9H11NO2+H | 166.0869 | 166.0853 | 9.6 | Pan, (2014) |

| 21 | Acetovanillone | Aromatics | C9H10O3+H | 167.0709 | 167.0709 | 0.0 | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 22 | Isatin | Alkaloids | C8H5NO2+Na | 170.0218 | 170.0221 | 1.8 | Zou and Koh, (2017) |

| 23 | 2,5-Dihydroxyindole | Alkaloids | C8H7NO2+Na | 172.0375 | 172.0388 | 7.6 | Li, (2010a) |

| 24 | Arginine | Amino acids | C6H14N4O2+H | 175.1196 | 175.1188 | 4.6 | Zeng et al. (2010) |

| 25 | 3-Indoleacetonitrile | Alkaloids | C10H8N2+Na | 179.0585 | 179.0592 | 3.9 | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 26 | Tyrosine | Amino acids | C9H11NO3+H | 182.0818 | 182.0800 | 9.9 | Pan, (2014) |

| 27 | Dihydroconiferyl alcohol | Phenylpropanoids | C10H14O3+H | 183.1022 | 183.1036 | 7.6 | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 28 | 4-Hydroxyindole-3-carboxaldehyde | Alkaloids | C9H7NO2+Na | 184.0375 | 184.0368 | 3.8 | Li et al. (2010b) |

| 29 | 2,4(1H,3H)-Quinazolinedione | Alkaloids | C8H6N2O2+Na | 185.0327 | 185.0326 | 0.5 | Wang and Liu, 2008 |

| 30 | Deoxyvasicinone | Alkaloids | C11H10N2O + H | 187.0872 | 187.0864 | 4.3 | Zhao, 2015 |

| 31 | 1-Methoxy-3-indoleformic acid | Alkaloids | C10H9NO3+H | 192.0661 | 192.0648 | 6.8 | Yang et al. (2014b) |

| 32 | (1′R,2′R,3′S,4′R)-1,2,4-triazole | Nucleosides | C7H11N3O4+H | 202.0829 | 202.0841 | 5.9 | Pan, (2014) |

| 33 | Tryptophan | Amino acids | C11H12N2O2+H | 205.0978 | 205.0959 | 9.3 | Pan, (2014) |

| 54 | L-targinine | Peptides | C7H16N4O2+Na | 211.1165 | 211.1150 | 7.1 | The Metabolomics Innovation Center, (2020) |

| 35 | (−)-(R)-2-(4-Hydroxy-2-oxoindolin-3-yl)-acetamide | Alkaloids | C10H10N2O3+Na | 229.0589 | 229.0576 | 5.7 | Chen et al. (2012) |

| 36 | 2′-Deoxyuridine | Nucleosides | C9H12N2O5+H | 229.0825 | 229.0842 | 7.4 | Pan, (2014) |

| 37 | (+)-(S)-2-(3-Hydroxy-4-methoxy-2-oxoindolin-3-yl)-acetamide | Alkaloids | C11H12N2O4+H | 237.0876 | 237.0899 | 9.7 | Chen et al. (2012) |

| 38 | 2′-Deoxycytidine | Nucleosides | C9H13N3O4+Na | 250.0804 | 250.0824 | 8.0 | Pan, (2014) |

| 39 | (S)-(−)-Spirobrassinin | Sulfur-containing compounds | C11H10N2OS2+H | 251.0314 | 251.0335 | 8.4 | Zhang et al. (2020b) |

| 40 | Pyrraline | Amino acids | C12H18N2O4+H | 255.1339 | 255.1332 | 2.7 | The Metabolomics Innovation Center, (2020) |

| 41 | Indiforine C | Alkaloids | C12H14N2O3+Na | 257.0902 | 257.0918 | 6.2 | Liu et al. (2018b) |

| 42 | Indirubin/indigotin | Alkaloids | C16H10N2O2+H | 211.0813 | 211.0821 | 3.0 | Chen et al. (2012) |

| 43 | Thymidine | Nucleosides | C10H14N2O5+Na | 265.0801 | 265.0824 | 8.7 | Pan, (2014) |

| 44 | Adenosine | Nucleosides | C10H13N5O4+H | 268.1047 | 268.1011 | 6.0 | Zhao, (2015) |

| 45 | Inosine | Nucleosides | C10H12N4O5+H | 269.0887 | 269.0905 | 6.7 | Pan et al. (2013) |

| 46 | Tryptanthrin | Alkaloids | C15H8N2O2+Na | 271.0484 | 271.0488 | 1.5 | Chen et al. (2012) |

| 47 | 2′-O-Methyladenosine | Nucleosides | C11H15N5O4+H | 282.1203 | 282.1221 | 6.4 | Zhang et al. (2019a) |

| 48 | Indican | Alkaloids | C14H17NO6+H | 296.0925 | 296.0935 | 3.4 | Zou and Koh, (2017) |

| 49 | Guanosine | Nucleosides | C10H13N5O5+Na | 306.0815 | 306.0824 | 2.9 | Xiao et al, (2014) |

| 50 | (−)-(2′S)-Isatiscaloids E/(+)-(2′R)-isatiscaloids E | Alkaloids | C14H19N3O5+H | 310.1404 | 310.1428 | 7.7 | Wang et al. (2009) |

| 51 | Isatiscaloids A | Alkaloids | C15H22N2O5+H | 311.1608 | 311.1627 | 6.1 | Wang et al. (2009) |

| 52 | Indiforine F | Alkaloids | C14H18N2O5+Na | 317.1114 | 317.1138 | 7.6 | Liu et al. (2018b) |

| 53 | Evofolin-B | Phenylpropanoids | C17H18O6+H | 319.1182 | 319.1160 | 6.9 | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 54 | Isatiscaloids B | Alkaloids | C16H20N2O5+H | 321.1451 | 321.1458 | 2.2 | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 55 | Adenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate | Nucleosides | C10H12N5O6P + H | 330.0604 | 330.0618 | 4.2 | Pan, (2014) |

| 56 | Indole-3-acetonitrile-6-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Alkaloids | C16H18N2O6+H | 335.1244 | 335.1240 | 1.2 | He et al. (2006a) |

| 57 | Isatisindigoticanine K | Alkaloids | C19H13N3O2+Na | 338.0906 | 338.0927 | 6.2 | Zhang et al. (2020c) |

| 58 | Coniferin | Phenylpropanoids | C16H22O8+H | 543.1394 | 543.1371 | 6.7 | Zhang et al. (2019a) |

| 59 | Isaindigodione | Alkaloids | C18H18N2O4+Na | 549.1165 | 549.1133 | 9.2 | Xiao et al. (2014) |

| 60 | Cyclo (L-Phe–L-Tyr) | Peptides | C18H18N2O3+Na | 549.2300 | 549.2320 | 5.7 | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 61 | Indole-3-acetonitrile-2-S-β-D-glucopyranoside | Sulfur-containing compounds | C16H18N2O5S + H | 351.1015 | 351.1005 | 2.8 | Yang et al. (2014b) |

| 62 | Qingdainone | Alkaloids | C23H13N3O2+ H | 364.1087 | 364.1079 | 2.2 | He et al. (2006a) |

| 11 | Isatindigotindoline C | Alkaloids | C23H21N3O4+H | 404.1611 | 404.1602 | 2.2 | Liu et al. (2018a) |

| 64 | Isatisindigoticanine A | Alkaloids | C22H18N2O6+H | 407.1244 | 407.1215 | 7.1 | Zhang et al. (2019b) |

| 65 | Isatindigobisindoloside G | Sulfur-containing compounds | C24H21N3O5S + H | 455.1278 | 455.1238 | 8.8 | Zhang et al. (2020a) |

| 66 | 3-[2′-(5′-hydroxymethyl)furyl]-1(2H)-isoquinolinone-7-O-β-D-glucoside | Alkaloids | C20H21NO9+K | 458.2199 | 458.2167 | 7.0 | He et al. (2006b) |

| 67 | Isatisindigoticanine I | Sulfur-containing compounds | C24H21N3O5S + H | 464.1281 | 464.1245 | 7.8 | Zhang et al. (2020a) |

| 68 | Isatindigoside F | Sulfur-containing compounds | C25H23N3O5S-H | 476.1279 | 476.1258 | 4.4 | Zhang et al. (2020a) |

| 69 | Isatigotindolediosides B | Alkaloids | C20H25NO11 + Na | 478.1326 | 478.1307 | 4.0 | Meng et al. (2017b) |

| 70 | Isatigotindolediosides A | Alkaloids | C21H27NO12 + H | 486.1612 | 486.1579 | 6.8 | Meng et al. (2017b) |

| 71 | Isatindigoside J | Alkaloids | C25H27N3O8+H | 498.1877 | 498.1892 | 3.0 | Zhang et al. (2020c) |

| 72 | Isatithioetherin A/isatithioetherin B | Sulfur-containing compounds | C20H26N4O4S3+Na | 505.1014 | 505.1058 | 8.7 | Guo et al. (2020b) |

| 73 | Bisindigotin | Alkaloids | C32H18N4O2+Na | 513.1328 | 513.1278 | 9.7 | Wei et al. (2005) |

| 74 | Isatigotindolediosides D | Alkaloids | C22H28N2O13 + H | 529.1670 | 529.1111 | 7.4 | Meng et al. (2017b) |

| 75 | Isatithioetherin C/isatithioetherin E | Sulfur-containing compounds | C20H26N4O4S4+Na | 537.0735 | 537.0784 | 9.1 | Guo et al. (2020b) |

| 76 | (+)-(7R,7′R,8S,8′S)-Neo-olivil | Phenylpropanoids | C26H54O12 + H | 539.2129 | 539.2143 | 2.6 | Kikuchiand Kikuchi, (2005) |

| 77 | (2S,3R)-3-Hydroxymethyl-N-(2′-hydroxynonacosanoyl)-trideca-9E-sphingenine | Sphingolipids | C43H85NO5+H | 696.6507 | 696.6565 | 8.3 | Li et al. (2007) |

| 78 | 1-O-β-D-Glucopyranosyl-(2S,3R)-N-(2′-hydroxyhe xacosanoyl)-octadeca-11E-sphingenine | Sphingolipids | C50H97NO9+H | 856.7242 | 856.7292 | 5.8 | Sun et al. (2009) |

| 79 | Propanedioic acid | Organic acids | C3H4O4-H | 103.0031 | 103.0040 | 8.7 | Li, (2010) |

| 80 | Pyrocatechol | Aromatics | C6H6O2-H | 109.0289 | 109.0294 | 4.6 | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 81 | Maleic acid/fumaric acid | Organic acids | C4H4O4-H | 115.0031 | 115.0040 | 7.8 | Peng et al. (2005b) |

| 82 | Nicotinic acid | Organic acids | C6H5NO2-H | 122.0241 | 122.0254 | 5.7 | Li, (2010) |

| 83 | 3-Methylfuran-2-carboxylic acid | Organic acids | C6H6O3-H | 125.0238 | 125.0243 | 4.0 | Zeng et al. (2010) |

| 84 | Goitrin/epigoitrin | Sulfur-containing compounds | C5H7NOS-H | 128.0169 | 128.0162 | 5.5 | Wang et al. (2014) |

| 85 | Malic acid | Organic acids | C4H6O5-H | 133.0136 | 133.0147 | 8.3 | Liu et al. (2010) |

| 86 | Salicylic acid | Organic acids | C7H6O3-H | 137.0238 | 137.0241 | 2.2 | Zhao, (2015) |

| 87 | Vanillin | Aromatics | C8H8O3-H | 151.0394 | 151.0388 | 4.0 | Sun et al., 2007 |

| 88 | Fructose/glucose | Saccharides | C6H12O6-H | 179.0555 | 179.0554 | 0.6 | Liu et al. (2010) |

| 89 | Mannitol | Saccharides | C6H14O6-H | 181.0711 | 181.0697 | 7.7 | He et al., 2006b |

| 90 | 2-Amine-4-quinlinecarboxylic acid | Alkaloids | C10H8N2O2-H | 187.0507 | 187.0517 | 5.3 | Pan, (2014) |

| 91 | Citric acid | Organic acids | C6H8O7-H | 191.0191 | 191.0191 | 0.0 | Liu et al. (2010) |

| 92 | Glucuronic acid | Organic acids | C6H10O7-H | 193.0548 | 193.0338 | 5.2 | Liu et al. (2010) |

| 93 | Syringic acid | Organic acids | C9H10O5-H | 197.0461 | 197.0449 | 6.1 | Wang et al. (2009) |

| 94 | Isatindosulfonic acid E | Sulfur-containing compounds | C9H9NO3S-H | 210.0224 | 210.0233 | 4.3 | Meng et al. (2017a) |

| 95 | Isatindosulfonic acid C | Sulfur-containing compounds | C10H11NO4S-H | 240.0330 | 240.0318 | 5.0 | Meng et al. (2017a) |

| 96 | Palmitic acid | Organic acids | C16H32O2-H | 255.2323 | 255.2542 | 7.4 | Kizil et al. (2009) |

| 97 | Emodin | Flavonoids | C15H10O5-H | 269.0449 | 269.0450 | 0.4 | Li, (2010) |

| 98 | Linolenic acid | Organic acids | C18H30O2-H | 277.2167 | 277.2172 | 1.8 | Kizil et al. (2009) |

| 99 | Calycosin | Flavonoids | C16H12O5-H | 283.0606 | 283.0111 | 8.8 | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 100 | Stearic acid | Organic acids | C18H36O2-H | 283.2116 | 283.2646 | 3.5 | Kizil et al. (2009) |

| 101 | Sucrose | Saccharides | C12H22O11-H | 541.1083 | 541.1089 | 1.8 | Liu et al. (2010) |

| 102 | Sinensetin | Flavonoids | C20H20O7- H | 371.1130 | 371.1103 | 7.3 | Li, (2010) |

| 103 | Gluconapin | Sulfur-containing compounds | C11H19NO9S2-H | 372.0422 | 372.0429 | 1.9 | Mohn et al. (2007) |

| 104 | Isatindigotindoloside C/Isatindigotindoloside D | Sulfur-containing compounds | C17H20N2O6S-H | 379.0911 | 379.0938 | 6.6 | Liu et al. (2015b) |

| 105 | Progoitrin/epiprogoitrin | Sulfur-containing compounds | C11H19NO10S2-H | 388.0371 | 388.0355 | 4.1 | Mohn et al. (2007) |

| 106 | Glucotropaeolin | Sulfur-containing compounds | C14H19NO9S2-H | 408.0422 | 408.0418 | 1.0 | Mohn et al. (2007) |

| 107 | Isovitexin | Flavonoids | C21H20O10-H | 431.0977 | 431.1012 | 8.1 | Zhao, (2015) |

| 108 | Glucobrassicin | Sulfur-containing compounds | C16H19N2O9S2-H | 447.0531 | 447.0537 | 1.3 | Guo et al. (2020a) |

| 109 | Isatindigobisindoloside A/isatindigobisindoloside B | Alkaloids | C24H23N3O6-H | 448.1508 | 448.1554 | 5.8 | Liu et al. (2015a) |

| 110 | Isatindigoside F | Sulfur-containing compounds | C25H23N3O5S-H | 476.1279 | 476.1258 | 4.4 | Zhang et al. (2020a) |

| 111 | Isatigotindolediosides F | Sulfur-containing compounds | C21H27NO12S-H | 516.1175 | 516.1153 | 4.3 | Meng et al. (2017b) |

| 112 | Isatigotindolediosides E | Sulfur-containing compounds | C22H28N2O11S-H | 527.1335 | 527.1284 | 9.7 | Meng et al. (2017b) |

| 113 | Isatigotindolediosides D | Sulfur-containing compounds | C22H28N2O13-H | 527.1512 | 527.1538 | 4.9 | Meng et al. (2017b) |

| 114 | Glucoisatisin/epiglucoisatisin | Sulfur-containing compounds | C21H26N2O12S2-H | 561.0848 | 561.0830 | 3.2 | Mohn and Hamburger, (2008) |

| 115 | Isovitexin | Flavonoids | C21H20O10-H | 431.0977 | 431.1012 | 8.1 | Zhao, (2015) |

| 116 | Linarin | Flavonoids | C28H32O14-H | 591.1713 | 591.1674 | 6.6 | Peng et al. (2005a) |

| 117 | Neohesperidin | Flavonoids | C28H54O15-H | 609.1819 | 609.1801 | 3.0 | Peng et al. (2005a) |

| 118 | Clemastanin B | Phenylpropanoids | C32H44O16-H | 683.2550 | 683.2489 | 8.9 | Yang et al. (2014a) |

Visualization of the Distribution of Phytochemicals in the Dried Root of Isatis tinctoria

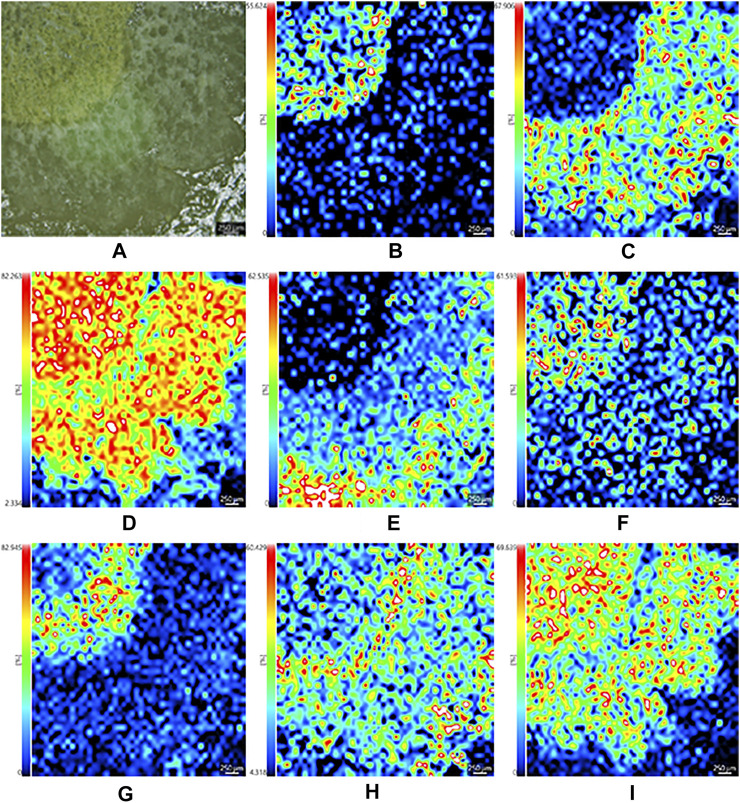

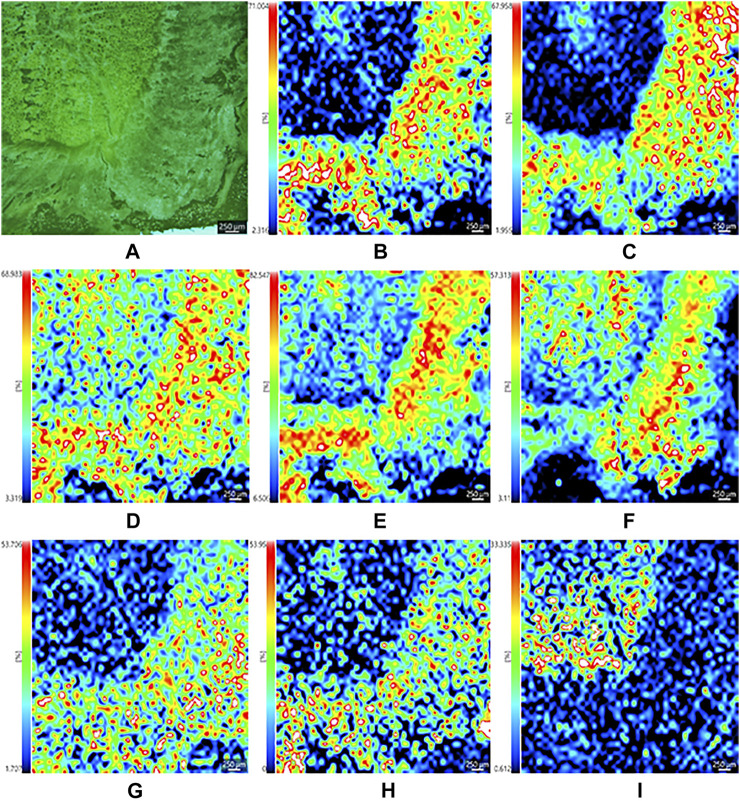

The optical images in Figures 3, 4 showed the main compartments of the cross section of the dried root of Isatis tinctoria: cork and cortex, phloem, cambium, and xylem as well as the distinctive spatial distribution of various kinds of characteristic constituents. The most abundant class of chemical components isolated from Isatis tinctoria is alkaloid. They were mostly detected as the positive ions and presented a variety of distributions. As could be seen from Figure 3B, sodium adduct of oxindole (m/z 156.0416), an indole alkaloid, was located exclusively in xylem. Another ion of m/z 458.2167 (Figure 3C) was found to have a different distribution in the specific region of phloem. This ion was assigned to the potassium adduct of 3-[2′-(5′-hydroxymethyl) furyl]-1(2H)-isoquinolinone-7-O-β-D-glucoside, an isoquinolinone alkaloid glycoside. Sulfur-containing compounds are characteristic secondary metabolites occurring in cruciferous plant, and they are the second abundant class of chemical components in Isatis tinctoria. Taking isatindigoside F (m/z 476.1258), a typical glucosinolate, as an example (Figure 4B), sulfur-containing compounds were mainly detected as the negative ions which accumulated mostly in phloem of the dried root of Isatis tinctoria. Dozens of phenylpropanoids are also found in Isatis indigotica, and they can be detected in positive or negative modes. Figure 3D and Figure 4C showed the spatial distribution of the ions of m/z 343.1371 and m/z 683.2479, which corresponded to the [M+H]+ and [M−H]− forms of the ions of coniferin and clemastanin B, a phenylpropanoid glycoside and a lignan diglucoside, respectively. Regardless of the form of the ions, the majority of the phenylpropanoids presented the highest abundance near the lateral area of the root, including phloem, cortex, and cork. Isatis root produces several nucleosides, which are normally observed as positive ions. MSI results suggested that the ion of m/z 152.0588 was assigned to the protonated adduct of guanine. As noticeable in the ion, it was located almost exclusively in xylem of the root. Moreover, mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) study on the constituents of the dried root of Isatis tinctoria revealed the presence of a variety of organic acids. The negative ions assigned as [M−H]− form of maleic acid (m/z 115.004), malic acid (m/z 133.0147, Figure 4E), and citric acid (m/z 191.0191, Figure 4F) were found at very high intensities in the area of phloem. Amino acids are widespread primary metabolites in plants, and they showed diversified distribution in the dried root of Isatis tinctoria in the form of the proton adducts. The protonated adduct of histidine at m/z 156.0786 (Figure 3F) was more abundant at the inner side of the cambium. On the contrary, another ion image concerned the distribution of proline at m/z 116.0709 (Figure 3G) with the highest abundance at the outer side of the cambium. Interestingly, the ion of arginine at m/z 175.1188 (Figure 3H) was located with prominent abundance in all tissues except regions of cambium, cortex, and cork. Ions based on phytochemicals belonging to minor groups in Isatis root like peptides, saccharides, flavonoids, and aromatics were also analyzed. It could be judged from Figure 3I that the highest concentration of a cyclic peptide named cyclo (L-Phe–L-Tyr) in the form of potassium adduct at m/z 349.2320 was in xylem and phloem. Sucrose is a nutritional ingredient that naturally occurs in many plants. Its negative ion at m/z 341.1089 (Figure 4G) was located mainly in the outer part of the root corresponding to the location of phloem, cortex, and cork. Similar distribution pattern was observed for the ion assigned to isovitexin (m/z 431.1012, Figure 4H), a representative flavone glycoside from Isatis root. Compounds belonging to aromatics are also isolated from Isatis root. This group includes vanillin, whose negative ion could be found at m/z 151.0388. In contrast to the above-discussed localization of two ions, this component accumulated at the area corresponding to xylem mainly (Figure 4I).

FIGURE 3.

Optical image of the dried root of Isatis indigotica (A) and the mass spectrometry images of the positive ions of oxindole (B), 3-[2′-(5′-hydroxymethyl)furyl]-1(2H)-isoquinolinone-7-O-β-D-glucoside (C), coniferin (D), guanine (E), histidine (F), proline (G), arginine (H), and cyclo (L-Phe–L-Tyr) (I).

FIGURE 4.

Optical image of the dried root of Isatis indigotica (A), and the mass spectrometry images of the negative ions of isatindigoside F (B), clemastanin B (C), maleic acid (D), malic acid (E), citric acid (F), sucrose (G), isovitexin (H), and vanillin (I).

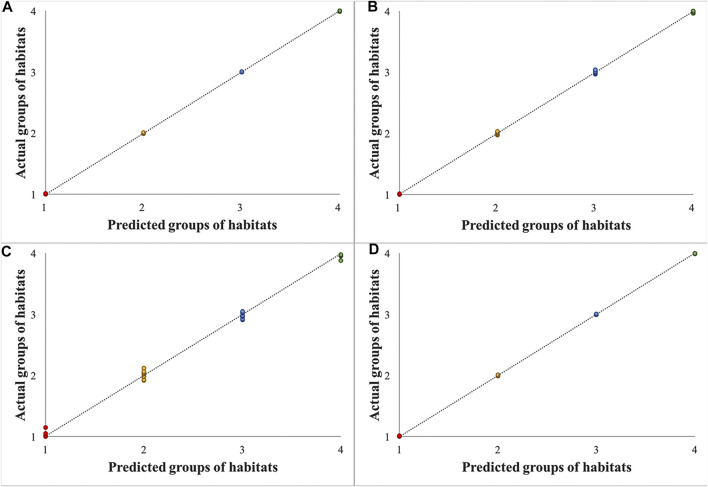

Differentiation of the Habitats of the Dried Root of Isatis tinctoria

Three repetitions for twelve samples of the dried root of Isatis tinctoria from Gansu, Xinjiang, Heilongjiang, and Neimenggu were first classified according to their habitats as groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) data of the whole tissues within two spectral ranges (m/z 100–500 and m/z 500–1,000) in positive and negative modes were input to establish four partial least square (PLS) regression models separately. Partial least square (PLS) regression was performed by importing the information of all detected ions to the X-matrix, while the actual groups of habitats were imported to the Y-matrix. As shown in Figure 5, good correlation between the predicted and actual groups of habitats of the dried root of Isatis tinctoria was found with all regression coefficients (R 2) above 0.99, which indicated an excellent discrimination ability of the mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) method.

FIGURE 5.

Results of partial least square (PLS) regression models for samples of the dried root of Isatis indigotica from four habitats based on mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) data in the spectral ranges of m/z 100–500 in a positive mode (A), m/z 500–1,000 in a positive mode (B), m/z 100–500 in a negative mode (C), and m/z 500–1,000 in a negative mode (D).

Discussion

In this study, iMScope, the optical microscope, in combination with the atmospheric pressure–matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (AP-MALDI) and the ion trap–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (IT-TOF/MS), was first applied to visually clarify the distribution of phytochemicals in the dried root of Isatis tinctoria. Nowadays, there have been increasing reports on the applications of mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) in the investigation of animal or human tissues (Wu et al., 2019), but with less focus on plants (Davison et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020d), not to mention traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). In addition, most of the research works were performed with the fresh herbs (Fowble et al., 2017; Lange et al., 2017; Freitas et al., 2019) due to the obstacles in the sectioning of the dried material. To reveal the spatial localization of phytochemicals in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in the form of actually sold in the market and used in clinic, the dried root of Isatis tinctoria was chosen as the imaging subject. As expected, the cryosectioning of the hard and fragile woody root presented great challenges.

First, the thickness of the tissue was optimized in the range from 20 to 80 μm. It was apparent that the thicker the slice, the more integrated the tissue, but thinner slice posed more sensitive detection of ions. Taking a comprehensive consideration of the integrity of the tissue and the quality of the mass data, a thickness of 40 μm was selected. Next, the temperature for cryosectioning of the frozen tissue was assessed in the range of −12–−22°C. It was found that the section would rupture when the temperature was too low, while when the temperature was too high, the section would wrinkle. Numerous trials indicated that satisfactory result could be obtained with a temperature of −18°C, which was coincident with the reported optimum cryosectioning parameter for the roots of Panax genus (Wang et al., 2016). Since the thin slice of the dried root of Isatis tinctoria was easy to fall off from the glass slide, a double-sided adhesive tape was utilized. To better avoid tissue break and movement during the sectioning, the sample surface was adhered by one side of the tape before cutting.

Subsequently, several matrices were evaluated as follows: 2′, 5′-dihydroxyacetophenone (2, 5-DHAP), 2, 5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB), α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA), and 1, 5-naphthalenediamine (1, 5-DAN) for the positive ion mode, and 1, 5-naphthalenediamine (1, 5-DAN), 9-aminoacridine (9-AA), 1, 8-bis(tetramethylguanidino) naphthalene (TMGN), and 1, 2-bis(trimethoxysilyl)ethane (BTME) for the negative ion mode. Briefly, comprehensive detection of molecules was achieved when using 2′, 5′-dihydroxyacetophenone (2, 5-DHAP) and 1, 5-naphthalenediamine (1, 5-DAN) as the matrixes in positive and negative ion modes, respectively. It was unexpected that DHB, the regular matric used in MALDI MSI of small molecules in plants, was not the most fitted matric for the dried root of Isatis tinctoria. In addition, two matrix-coating modes, air-assisted spraying and sublimation, were compared, and the results indicated that spraying presented stronger signal intensity and miner analyte delocalization.

As a result, 118 ions in the dried root of Isatis tinctoria were assigned as 10 classes of components including some bioactive molecules. Not surprisingly, the majority of the identified phytochemicals belonged to alkaloids and sulfur-containing compounds. The second most detected components were nucleosides, organic acids, and amino acids. A few aromatics, flavonoids, phenylpropanoids, saccharides, peptides, and sphingolipids were also found. On the contrary, esters, quinones, terpenes, sterols, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, and nitriles from Isatis indigotica were not detected by mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) this time. Like fructose and glucose, several alkaloids, sulfur-containing compounds, amino acids, and saccharides were grouped together in Table 2 since they hold isomeric relationship and could not be differentiated by their exact mass. Hence, further work should be done for the separation of the detected isomers. The presence of most of the identified components was previously found in Isatis indigotica except choline, dopamine, L-targinine, and pyrraline, which might be caused by the loss during the extraction and separation process in routine methods. Therefore, the matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization and ion trap–time-of-flight (MALDI-IT-TOF) mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) in a single run covered not only the natural products that were commonly detected but also less reported molecules, illustrating the high throughput and high sensitivity of the method. It was also delighted to find that a couple of important bioactive molecules (references could be seen in Table 2) from Isatis indigotica, such as uracil, adenine, hypoxanthine, 4(3H)-quinazolinone, deoxyvasicinone, 2,4(1H,3H)-quinazolinedione, isalexin, guanine, indirubin, and indigotin, were identified in an untargeted, label-free, and multiplexed way without extraction or isolation. Among them, uracil, adenine, guanine, indirubin, and indigotin are often used as the chemical markers for authentication of the root of Isatis indigotica, and they were detected in all the investigated samples. Using mass spectrometry imaging, the herb could be identified in a rapid way with multiple indexes, comparing to routine TLC or HPLC methods.

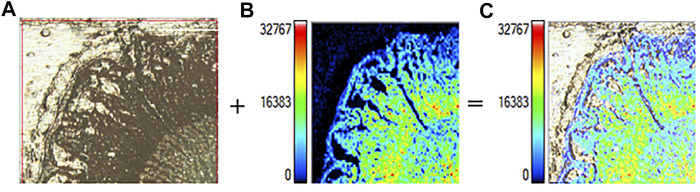

As indicated in Figure 6, the optical microscope embedded in the iMScope made it possible to acquire optical images and ion distribution images in the same instrument. The convenient assessment allowed for an unprecedented visualization of the spatial distribution of phytochemicals in the dried root of Isatis indigotica. Consequently, the localization and spatial information of some molecules in the root tissue were elucidated, which were related to the botanical structure of the herb. In all, a majority of the phytochemicals were shown to be more abundant in phloem, the nutrition-storing tissue of Isatis indigotica, than in xylem, the principle water-conducting tissue. Nevertheless, the signals for some identified constituents were considerably lower, and their mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) localization was therefore not so distinctive. Comparing with the LC-MS analysis after laser microdissection, microscopic mass spectrometry imaging using matrix-assisted laser desorption can reveal the spatial distribution of compounds in a more precise and direct way. Besides, segmentation and dissection might bring uncontrollable pollution, compound migration, or denaturation. However, the differentiation of isomers and absolute quantitation were not available by MALDI-MSI currently.

FIGURE 6.

Optical image (A), mass spectrometry image (B), and overlay image (C) of the dried root of Isatis indigotica.

Finally, based on the ion images, data were collected from the whole tissue and analyzed by partial least squares (PLSs), and the dried root of Isatis indigotica from four habitats was differentiated unambiguously. Spectra collected from the whole tissue, the outer part of the tissue (cork, cortex, and phloem), and the inner part of the tissue (cambium and xylem) were also inputted for principal component analysis (PCA). However, no distinct cluster was observed for samples from different habitats.

Among other possibilities, the results from this study can be applied to increase the extraction yield of a given active component in Isatis indigotica, which is promising in research fields, such as pharmaceutical applications and industrial production. Moreover, the location of specific metabolites is helpful to improve the understanding of the relationship between compound distribution and plant structure as well as function. Combining with the chemometric method, mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) provides a simple and rapid approach for distinguishing habitats of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and exploring the environmental effects of plant growth. Finally, similar studies on other traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) are underway in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical advice provided by Shuang-shuang Di and Honggang Nie from Beijing National Laboratory for Molecular Sciences, College of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering, Peking University.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Author Contributions

LN designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. JD, LH, CL, and XQ assisted in performing the experiments. SK collected and authenticated the dried root of Isatis indigotica. ZD and SM revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81303194).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chen M., Gan L., Lin S., Wang X., Li L., Li Y., et al. (2012). Alkaloids from the Root of Isatis Indigotica. J. Nat. Prod. 75, 1167–1176. 10.1021/np3002833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condurso C., Verzera A., Romeo V., Ziino M., Trozzi A., Ragusa S. (2006). The Leaf Volatile Constituents of Isatis Tinctoria by Solid-phase Microextraction and Gas Chromatography/mass Spectrometry. Planta Med. 72, 924–928. 10.1055/s-2006-946679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison A. S., Strittmatter N., Sutherland H., HughesHughes A. T. J., Hughes J., Bou-Gharios G., et al. (2019). Assessing the Effect of Nitisinone Induced Hypertyrosinaemia on Monoamine Neurotransmitters in Brain Tissue from a Murine Model of Alkaptonuria Using Mass Spectrometry Imaging. Metabolomics. 15, 68–77. 10.1007/s11306-019-1531-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowble K. L., Teramoto K., Cody R. B., Edwards D., Guarrera D., Musah R. A. (2017). Development of "Laser Ablation Direct Analysis in Real Time Imaging" Mass Spectrometry: Application to Spatial Distribution Mapping of Metabolites along the Biosynthetic Cascade Leading to Synthesis of Atropine and Scopolamine in Plant Tissue. Anal. Chem. 89, 3421–3429. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas J. R. L., Vendramini P. H., Melo J. O. F., Eberlin M. N., Augusti R. (2019). Assessing the Spatial Distribution of Key Flavonoids in Mentha × Piperita Leaves: An Application of Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry Imaging (DESI-MSI). J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 30, 1437–1446. 10.21577/0103-5053.20190039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Sun Y., Tang Q., Zhang H., Cheng Z. (2020a). Isolation, Identification, Biological Estimation, and Profiling of Glucosinolates in Isatis Indigotica Roots. J. Liquid Chromatogr. Relat. Tech. 43, 645–656. 10.1080/10826076.2020.1780605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Xu C., Chen M., Lin S., Li Y., Zhu C., et al. (2018b). Sulfur-enriched Alkaloids from the Root of Isatis Indigotica. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 8, 933–943. 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L. W., Li X., Chen J. W., Sun D. D. (2006a). Studies on Water-Soluble Chemical Constitutions in Radix Isatidis. Chin. Pharm. J. 17, 232–234. 10.3969/j.issn.1001-0408.2006.03.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He L. W., Li X., Chen J. W., Sun D. D., Jü W. Z., Wang K. C. (2006b). [Chemical Constituents from Water Extract of Radix Isatidis]. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 41, 1193–1196. 10.1097/00024382-200610001-00089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y. Q., Zhou C. C., Yu L. Y., Wang L., Deng J. L., Tao Y. L., et al. (2020). Natural Product Derived Phytochemicals in Managing Acute Lung Injury by Multiple Mechanisms. Pharmacol. Res. 163, 105224. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HighChem L. L. C. (2020). MzCloud Mass Spectral Library. Available at: https://www.mzcloud.org/((Accessed 12, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi M., Kikuchi M. (2005). Studies on the Constituents of Swertia Japonica MAKINO II. On the Structures of New Glycosides. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 53, 48–51. 10.1248/cpb.53.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizil S., Turk M., Çakmak Ö., Özgüven M., Khawar K. M. (2009). Microelement Contents and Fatty Acid Compositions of Some Isatis Species Seeds. Not. Bot. Horti. Agrobot. Cluj. Napoca. 37, 175–178. 10.15835/nbha3713115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lange B. M., Fischedick J. T., Lange M. F., Srividya N., Šamec D., Poirier B. C. (2017). Integrative Approaches for the Identification and Localization of Specialized Metabolites in Tripterygium Roots. Plant Physiol. 173, 456–469. 10.1104/pp.15.01593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-g., Xu H. (2021). Chinese Medicine in Fighting against COVID-19: Role and Inspiration. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 27, 3–6. 10.1007/s11655-020-2860-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wang X., HanJia L. L., Jia L., Liu E., Li Z., et al. (2020a). Integration of Multicomponent Characterization, Untargeted Metabolomics and Mass Spectrometry Imaging to Unveil the Holistic Chemical Transformations and Key Markers Associated with Wine Steaming of Ligustri Lucidi Fructus. J. Chromatogr. A. 1624, 461228. 10.1016/j.chroma.2020.461228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. F., Hou Y. L., Huang J. C., Pan W. Q., Ma Q. H., Shi Y. X., et al. (2020b). Lianhuaqingwen Exerts Anti-viral and Anti-inflammatory Activity against Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Pharmacol. Res. 156, 104761. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Zhu N., Tang C., Duan H., Wang Y., Zhao G., et al. (2020c). Differential Distribution of Characteristic Constituents in Root, Stem and Leaf Tissues of Salvia Miltiorrhiza Using MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging. Fitoterapia. 146, 104679. 10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Tao P. (2013). Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine as a Source of Molecules with Antiviral Activity. Antivir. Res. 97, 1–9. 10.1186/s13020-016-0074-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. (2010). Chemical Constituents and Quality Control of Radix Isatidis. [master’s Thesis]. [Changzhi (Shanxi)]: Shanxi Medicinal University; [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Chen A. J., Li C. (2010). Studies on Water-Soluble Chemical Constituent in Radix Isatidis. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Form. 16, 64–67. 10.13422/j.cnki.syfjx.2010.05.037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z., Chen Y., Xu L., Qin M., Yi T., Chen H., et al. (2014a). Localization of Ginsenosides in the Rhizome and Root of Panax Ginseng by Laser Microdissection and Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole/time of Flight-Mass Spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 105, 121–133. 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z., Oh K., Wang Y., Yi T., Chen H., Zhao Z. (2014b). Cell Type-specific Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Saikosaponins in Three Bupleurum Species Using Laser Microdissection and Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole/time of Flight-Mass Spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 97, 157–165. 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.-W., Tsai F.-J., Tsai C.-H., Lai C.-C., Wan L., Ho T.-Y., et al. (2005). Anti-SARS Coronavirus 3C-like Protease Effects of Isatis Indigotica Root and Plant-Derived Phenolic Compounds. Antiviral Res. 68, 36–42. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Sun D.-D., Chen J.-W., He L.-W., Zhang H.-Q., Xu H.-Q. (2007). New Sphingolipids from the Root of Isatis Indigotica and Their Cytotoxic Activity. Fitoterapia. 78, 490–495. 10.1016/j.fitote.2007.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Yan J., Li H. L., Song F. R., Liu Z. Y., Liu Z. Q., et al. (2010). Studies on Chemical Constituents of Compound Indigowoad Root Granule by Mass Spectrometry. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 31, 1137–1142. 10.1016/S1872-2040(09)60019-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.-F., Lin B., Xi Y.-F., Zhou L., Lou L.-L., Huang X.-X., et al. (2018a). Bioactive Spiropyrrolizidine Oxindole Alkaloid Enantiomers from Isatis Indigotica Fortune. Org. Biomol. Chem. 16, 9430–9439. 10.1039/C8OB02046A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.-F., Zhang Y.-Y., Zhou L., Lin B., Huang X.-X., Wang X.-B., et al. (2018b). Alkaloids with Neuroprotective Effects from the Leaves of Isatis Indigotica Collected in the Anhui Province, China. Phytochemistry 149, 132–139. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.-F., Chen M.-H., Guo Q.-L., LinXu S. C. B., Xu C.-B., Jiang Y.-P., et al. (2015a). Antiviral Glycosidic Bisindole Alkaloids from the Roots ofIsatis Indigotica. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 17, 689–704. 10.1080/10286020.2015.1055729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.-F., Chen M.-H., Lin S., Li Y.-H., Zhang D., Jiang J.-D., et al. (2015b). Indole Alkaloid Glucosides from the Roots of Isatis Indigotica. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 18, 1–12. 10.1080/10286020.2015.1117452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Liu L. F., Wang X. H., Li W., Jie C., Chen H., et al. (2019). Epigoitrin, an Alkaloid from Isatis Indigotica, Reduces H1N1 Infection in Stress-Induced Susceptible Model In Vivo and In Vitro . Front. Pharmacol. 10, 78. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L., Guo Q., Liu Y., Chen M., Li Y., Jiang J., et al. (2017a). Indole Alkaloid Sulfonic Acids from an Aqueous Extract of Isatis Indigotica Roots and Their Antiviral Activity. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 7, 334–341. 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L.-J., Guo Q.-L., Xu C.-B., Zhu C.-G., Liu Y.-F., Chen M.-H., et al. (2017b). Diglycosidic Indole Alkaloid Derivatives from an Aqueous Extract of Isatis Indigotica Roots. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 19, 529–540. 10.1080/10286020.2017.1320547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohn T., Cutting B., Ernst B., Hamburger M. (2007). Extraction and Analysis of Intact Glucosinolates-A Validated Pressurized Liquid Extraction/liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Protocol for Isatis Tinctoria, and Qualitative Analysis of Other Cruciferous Plants. J. Chromatogr. A 1166, 142–151. 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohn T., Hamburger M. (2008). Glucosinolate Pattern inIsatis tinctoriaandI. indigoticaSeeds. Planta Med. 74, 885–888. 10.1055/s-2008-1074554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng K.-M., Liang Z., Lu W., Tang H.-W., Zhao Z., Che C.-M., et al. (2007). In Vivo analysis and Spatial Profiling of Phytochemicals in Herbal Tissue by Matrix-Assisted Laser desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 79 (7), 2745–2755. 10.1021/ac062129i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y. L. (2014). Study the Chemical Composition of Effective Extraction of Isatidis Radix and its Composition Analysis of Different Regions. [master’s Thesis]. [Nanjing (Jiangsu)]: Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine; [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y., Xue P., Li X., ChenLi J. J., Li J. (2013). Determination of Nucleosides and Nucleobases in Isatidis Radix by HILIC-UPLC-MS/MS. Anal. Methods. 5, 6395–6400. 10.1039/C3AY40841H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S. P., Gu Z. L. (2005a). Recent Progress in the Studies of Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Effects on Roots of Isatis Indigotica, Chin . Wild Plant Res. 24, 4–7. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-9690.2005.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y., Zhang L. P., Song H., Pan W. S., Sun Y. Q. (2005b). The Chemical Constituents from Isatis Indigotica Fort, I. Chin. J. Med. Chem. 15, 371–372. 10.14142/j.cnki.cn21-1313/r.2005.06.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y.-H., Xie Z.-Y., Wang R., Huang S.-J., Li Y.-M., Wang Z.-T. (2012). Quantitative and Chemical Fingerprint Analysis for the Quality Evaluation of Isatis Indigotica Based on Ultra-performance Liquid Chromatography with Photodiode Array Detector Combined with Chemometric Methods. Int J Mol Sci. 13, 9035–9050. 10.3390/ijms13079035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimma S., Sagawa T. (2019). Microscopy and Mass Spectrometry Imaging Reveals the Distributions of Curcumin Species in Dried Turmeric Root. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 9652–9657. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b02768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speranza J., Miceli N., Taviano M. F., Ragusa S., Kwiecień I., Szopa A., et al. (2020). Isatis Tinctoria L. (Woad): A Review of its Botany, Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, and Biotechnological Studies. Plants. 9, 298. 10.3390/plants9030298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Wang F., Zhang Y., Yu J., Wang X. (2020). Mass Spectrometry Imaging-Based Metabolomics to Visualize the Spatially Resolved Reprogramming of Carnitine Metabolism in Breast Cancer. Theranostics. 10, 7070–7082. 10.7150/thno.45543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D. D., He L. W., Li X., Chen J. W., Ding L. (2007). Study on Chemical Constituents of Radix Isatidis. Chin. Pharm. J. 18, 172–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sun D., Dong W., Li X., Zhang H. (2009). Isolation, Structural Determination and Cytotoxic Activity of Two New Ceramides from the Root of Isatis Indigotica. Sci. China Ser. B-chem. 52, 621–625. 10.1007/s11426-008-0146-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Metabolomics Innovation Centre (2020). The Human Metabolome Database. Available at: https://hmdb.ca/(Accessed December 12, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Runco J., Yang L., Yu K., Li Y., Chen R., et al. (2014). Qualitative and Quantitative Analyses of Goitrin-Epigoitrin in Isatis Indigotica Using Supercritical Fluid Chromatography-Photodiode Array Detector-Mass Spectrometry. RSC Adv. 4, 49257–49263. 10.1039/c4ra02705a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Bai H., Cai Z., Gao D., Jiang Y., Liu J., et al. (2016). MALDI Imaging for the Localization of Saponins in Root Tissues and Rapid Differentiation of Three Panax Herbs. Electrophoresis 37, 1956–1966. 10.1002/elps.201600027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. Y., Zhou H., Wang Y. F., Sang B. S., Liu L. (2021). Current Policies and Measures on the Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine in China. Pharmacol. Res. 163, 105187. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zheng W., Xie G., Qiu M., Jia W. (2009). [Determination of Salylic Acid, Syringic Acid, Benzoic Acid and Anthranilic Acid in Radix Isatidis by HPCE]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 34, 189–192. 10.3321/j.issn:1001-5302.2009.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. F., Liu Y. H. (2008). Anti-endotoxic Effects of 3-(2'-Carboxyphenyl)-4(3h)-Quinazolinone from Radix Isatidis. Lishizhen Med. Mat. Med. Res. 19, 262–264. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-0805.2008.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. L., Chen M. H., Wang F., Pu P. B., Lin S., Zhu C. G., et al. (2013). Chemical Constituents from Root of Isatis Indigotica. China J. Chin. Mate. Med. 38, 1172–1182. 10.4268/cjcmm2013081210.1080/03632415.2013.848346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X. Y., Leung C. Y., Wong C. K. C., Shen X. L., Wong R. N. S., Cai Z. W., et al. (2005). Bisindigotin, a TCDD Antagonist from the Chinese Medicinal HerbIsatis Indigotica. J. Nat. Prod. 68, 427–429. 10.1021/np049662i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Dai Z., Liu X., Lin M., Gao Z., Tian F., et al. (2019). Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of Shenfu Injection in Rats with Ischemic Heart Failure and its Effect on Small Molecules Using Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Mass Spectrometry Imaging. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1424. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W., Liang Z., Zhao Z., Cai Z. (2007). Direct Analysis of Alkaloid Profiling in Plant Tissue by Using Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/ionization Mass Spectrometry. J. Mass. Spectrom. 42 (1), 58–69. 10.1002/jms.1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Qin G., Cheung K. K., Cheng K. F. (1997). New Alkaloids from Isatis Indigotica. Tetrahedron 53, 13323–13328. 10.1016/S0040-4020(97)00846-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S., Bi K., Sun Y. (2007). Identification of Chemical Constituents in the Root of Isatis Indigotica Fort. By LC/DAD/ESI/MS/MS. J. Liquid Chromatogr. Relat. Tech. 30, 73–85. 10.1080/10826070601034295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S. S., Jin Y., Sun Y. Q. (2003). Recent Progress in the Studies of Chemical Constituents, Pharmacological Effects and Quality Control Methods on the Roots of Isatis Indigotica. J. Shenyang Pharm. Univ. 20, 455–459. 10.14066/j.cnki.cn21-1349/r.2003.06.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Jiang H., Wang G., Wang M., Ding L., Chen L., et al. (2014a). Phenylpropanoids and Some Nitrogen-Containing Constituents from the Roots of Isatis Indigotica Fort. (Cruciferae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 54, 313–315. 10.1016/j.bse.2014.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Wang G., Wang M., Jiang H., Chen L., Zhao F., et al. (2014b). Indole Alkaloids from the Roots of Isatis Indigotica and Their Inhibitory Effects on Nitric Oxide Production. Fitoterapia. 95, 175–181. 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi L., Liang Z.-T., Peng Y., Yao X., Chen H.-B., Zhao Z.-Z. (2012). Tissue-specific Metabolite Profiling of Alkaloids in Sinomenii Caulis Using Laser Microdissection and Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole/time of Flight-Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 1248, 93–103. 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.05.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J., Guo Z., Xiao Y., Wang C., Zhang X., Liang X. (2010). Purification of Polar Compounds from Radix Isatidis Using Conventional C18 Column Coupled with Polar-Copolymerized C18 Columncation of Polar Compounds from Radix Isatidis Using Conventional C18 Column Coupled with Polarcopolymerized C18 Column. J. Sep. Sci. 33, 3341–3346. 10.1002/jssc.201000417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. D., Li Q. Y., Shi H. Y., Chen K. X., Li Y. M., Wang R. (2019a). Glycosides from Roots of Isatis Indigotica. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs. 50, 3575–3588. 10.7501/j.issn.0253-2670.2019.15.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Shi Y., Li J., Ruan D., JiaZhu Q. W. L., Zhu W., et al. (2019b). Alkaloids with Nitric Oxide Inhibitory Activities from the Roots of Isatis Tinctoria. Molecules. 24, 4033–4042. 10.3390/molecules24224033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Ruan D., Li J., Chen Z., Zhu W., Guo F., et al. (2020a). Four Undescribed Sulfur-Containing Indole Alkaloids with Nitric Oxide Inhibitory Activities from Isatis Tinctoria L. Roots. Phytochemistry 174, 112337. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. D., Ruan D. Q., Li Q, Y., Chen K. X., Li Y. M., Wang R. (2020b). Study on Alkaloids from Alcohol Extract of Radix Isatidis. CJTCMP. 35, 2287–2291. CNKI:SUN:BXYY.0.2020-05-018 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Sun Y., Chen Z., JiaZhu Q. W. L., Zhu W., Chen K., et al. (2020c). Bisindole Alkaloids with Nitric Oxide Inhibitory Activities from an Alcohol Extract of the Isatis Indigotica Roots. Fitoterapia. 146, 104654. 10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Du Q., SongGao X. S. S., Gao S., Pang X., Li Y., et al. (2020d). Evaluation of the Tumor-Targeting Efficiency and Intratumor Heterogeneity of Anticancer Drugs Using Quantitative Mass Spectrometry Imaging. Theranostics. 10, 2621–2630. 10.7150/thno.41763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N. (2015). Study on the Serum Pharmacochemistry of Banlangen Based on the LC-MS. [master’s Thesis]. [Haerbin (Heilongjiang)]: Heilongjiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine; [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Zhang X.-Y. (2013). Research Progress of Chinese Herbal Medicine Radix Isatidis (Banlangen). Am. J. Chin. Med. 41, 743–764. 10.1142/s0192415x1350050x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou P., Hong Y., Koh H. L. (2005). Chemical Fingerprinting of Isatis Indigotica Root by RP-HPLC and Hierarchical Clustering Analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 38, 514–520. 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou P., Koh H. L. (2007). Determination of Indican, Isatin, Indirubin and Indigotin inIsatis Indigotica by Liquid Chromatography/electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 21, 1239–1246. 10.1002/rcm.2954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.