Abstract

Objectives:

This study examined changes in the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies by U.S. adults aged 18 years or older with chronic disease-related functional limitations between 2002 and 2007.

Design:

The study was a cross-sectional survey.

Setting/location:

The study was conducted in the United States.

Subjects:

The study comprised adults aged 18 years or older with chronic disease-related functional limitations.

Methods:

Data were obtained from the 2002 and 2007 U.S. National Health Interview Survey to compare the use of 22 CAM therapies (n = 9313 and n = 7014, respectively). Estimates were age adjusted to the year 2000 U.S. standard population.

Results:

The unadjusted and age-standardized prevalence of overall CAM use (22 therapies comparable between both survey years) was higher in 2007 than in 2002 (30.6% versus 26.9%, p < 0.001 and 34.4% versus 30.6%, p < 0.001, respectively). Adults with functional limitations that included changing and maintaining body position experienced a significant increase in CAM use between 2002 and 2007 (31.1%–35.0%, p < 0.01). The use of deep breathing exercises was the most prevalent CAM therapy in both 2002 and 2007 and increased significantly during this period (from 17.9% to 19.9%, p < 0.05). The use of meditation, massage, and yoga also increased significantly from 2002 and 2007 (11.0%–13.5%, p < 0.01; 7.0%–10.9%, p < 0.0001; and 5.1% to 6.6%, p < 0.05, respectively), while the use of the Atkins diet decreased (2.2%– 1.4%, p < 0.01).

Conclusions:

Among U.S. adults with chronic disease-related functional limitations, the overall increase in CAM use from 2002 to 2007 was significant, particularly among those with changing and maintaining body position limitations.

Introduction

In the United States, overall complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use increased substantially during the 1990s1,2 but has remained relatively stable since.3–5 In 1990, Eisenberg et al.2 estimated that 33.8% of U.S. adults (60 million) had used at least 1 of 16 CAM therapies in the past year, representing approximately 427 million visits to CAM practitioners. In a trend analysis of CAM use between 1990 and 1997, Eisenberg et al.1 reported that the prevalence of overall CAM use had increased significantly from 33.8% to 42.1% (83 million), and that this population incurred an estimated $27 billion in out-of-pocket expenditures on 629 million visits to CAM practitioners ($12.2 billion) and CAM classes and products ($14.8 billion). Subsequent analyses of CAM use conducted between 1997 and 20024 and 2002 and 20073,6 found that the prevalence of CAM use had remained relatively stable; however, self-care therapies (e.g., nonvitamin, nonmineral, natural products; homeopathic products; and yoga) consumed a greater proportion of dollars spent on CAM. In 2007, Barnes et al.3 estimated that 38.3% of U.S. adults (83 million) used a CAM therapy in the past year and Nahin et al.6 estimated $33.9 billion in out-of-pocket expenditures on 354 million visits to CAM practitioners ($11.9 billion) and purchases of CAM classes and products ($22.0 billion).

Nonetheless, while overall CAM use has remained relatively stable since the late 1990s, substantial variation in the use of specific CAM therapies has been seen during this same time period. In an examination of 15 comparable CAM therapies between 1997 and 2002, increased use was seen among adults for yoga and herbal medicine, while chiropractic use decreased.4 Similarly, in an examination of 22 specific CAM therapies between 2002 and 2007, the greatest increase in use was seen for massage therapy, meditation, deep breathing exercises, and yoga, while use of the Atkins diet and t’ai chi decreased.3 Several factors may explain the variability seen in the use of CAM therapies over time. Such factors may include state licensure and availability of CAM practitioners6,7; increased health insurance coverage of visits to CAM practitioners and specific CAM therapies6,8–10; inclusion of CAM in medical school curriculums11–13; and integration of CAM practitioners and therapies into the practice of conventional medicine.14–16 In addition, as the safety and efficacy of specific CAM therapies are validated by scientific studies, subsequent integration into clinical guidelines may increase their use. For example, on the basis of a systematic review of nonpharmacologic therapies available for treatment of chronic back pain,17 the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society jointly recommend that clinicians consider the use of several CAM therapies (e.g., acupuncture, massage therapy, progressive relaxation, spinal manipulation, and Viniyoga-style yoga) for patients who do not improve with self-care options (e.g., medium-firm mattress; education books).18

Adults use CAM therapies for a variety of reasons, such as management of existing health conditions, disease prevention, and general well-being.3,19,20 Adults with functional limitations, who generally have higher health care utilization rates and expenditures compared to adults without limitations,21,22 are also more likely to use CAM.2,3–26 Moreover, compared to adults without functional limitations, those with limitations have been found to be more likely to use CAM for treatment of a health condition than for noncondition use.27,28 At a population level, information on recent trends in overall use of CAM and use of specific CAM therapies is lacking among adults with functional limitations. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the use of CAM between 2002 and 2007 among adults with chronic disease-related functional limitations. First, it was examined whether changes in overall CAM use varied by functional status as defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF).29 Second, changes in the use of 22 comparable CAM therapies between 2002 and 2007 were examined.

Materials and Methods

Study design and sample

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is a computer-assisted personal interview survey of a nationally representative sample of the community-dwelling U.S. population. The survey is conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).30 In 2002 and 2007, the NCHS and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine cosponsored an Adult Complementary and Alternative Medicine (ACAM) supplement to the NHIS to estimate the national prevalence and reasons for use of CAM therapies among adults aged 18 years or older. NHIS methodology and data-weighting procedures are fully described else-where.30,31 Data from the ACAM supplements and core components of the NHIS were used to compare the use of CAM therapies among adults with chronic disease-related functional limitations between 2002 and 2007 (n = 9313 and n = 7014, respectively).

Measures

Functional limitations.

Twelve (12) functional tasks were assessed with the following questions: "The next questions ask about difficulties you may have doing certain activities because of a HEALTH PROBLEM. By ‘health problem’ we mean any physical, mental, or emotional problem or illness (not including pregnancy). By yourself, and without using any special equipment, how difficult is it for you to... ‘walk a quarter of a mile—about 3 city blocks’; ‘walk up 10 steps without resting’; ‘stand or be on your feet for about 2 hours’; ‘sit for about 2 hours’; ‘stoop, bend, or kneel’; ‘reach up over your head’; ‘use your fingers to grasp or handle small objects’; ‘lift or carry something as heavy as 10 pounds such as a full bag of groceries’; ‘push or pull large objects like a living room chair’; ‘go out to things like shopping, movies, or sporting events’; ‘participate in social activities such as visiting friends, attending clubs and meetings, going to parties’; and ‘do things to relax at home or for leisure (reading, watching TV, sewing, listening to music).’ " Responses were categorized as 0 (not difficult at all), 1 (only a little difficult), 2 (somewhat difficult), 3 (very difficult), and 4 (can’t do at all). Respondents were considered to have a chronic disease-related functional limitation if they reported any difficulty in the performance of ≥ 1 of the 12 assessed tasks, and the limitation resulted from ≥1 of 36 chronic conditions.32 Respondents who answered "don’t know," refused to respond, or who had missing responses for any of the 12 questions were excluded. Also excluded were respondents whose limitation was not caused by a chronic condition or the cause of limitation was unknown.

Using these 12 tasks, 4 functional status measures were defined using the ICF.29 These were (1) changing and maintaining body position—standing, sitting, stooping, or reaching; (2) carrying, moving, and handling objects— grasping, carrying, or pushing; (3) walking and moving around—walking or climbing; and (4) recreation and leisure— shopping, socializing, or relaxing.

Complementary and alternative medicine therapies.

Twenty-two (22) CAM therapies that were comparable between 2007 and 2002 were assessed: acupuncture, Ayurveda, homeopathy, naturopathy, chelation therapy, diet-based therapies (i.e., vegetarian diet; macrobiotic diet; Atkins diet; Pritikin diet; Ornish diet; Zone diet), massage, biofeedback, relaxation techniques (i.e., meditation; guided imagery; progressive relaxation; and deep-breathing exercises), hypnosis, yoga, t’ai chi, qigong, and energy healing. For each of the 22 CAM therapies, use in the past 12 months was determined by a "yes" response to the following questions: "During the past 12 months." "did you see a practitioner for acupuncture"; "did you see a practitioner for Ayurveda"; "did you use homeopathic treatment for your own healt"; "did you see a practitioner for naturopathy"; "did you see a practitioner for chelation therapy"; "did you use a [vegetarian diet, macrobiotic diet, Atkins diet, Pritikin diet, Ornish diet, Zone diet] for two weeks or more for health reasons"; "did you see a practitioner for massage"; "did you see a practitioner for biofeedback"; "did you use [meditation, guided imagery, progressive relaxation, deep breathing exercises] for yourself"; "did you see a practitioner for hypnosis"; "did you practice [yoga, t’ai chi, qigong]"; and "did you see a practitioner for energy healing therapy."

Statistical analyses.

First, sociodemographic characteristics of adults with functional limitations in 2002 and 2007 were examined. These sociodemographic characteristics included age in years (18–24, 25–44, 45–64, and ≥ 65), gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic [nH] white, nH black, Hispanic, and nH other), education (< high school, high school, and ≥ college), imputed family income (< $20,000, $20,000– $34,999, $35,000–$64,999, and ≥ $65,000),32 and U.S. Census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West). Second, the crude and age-standardized prevalence of overall CAM use in 2002 and 2007 was estimated. Third, the prevalence of use of 22 individual CAM therapies common to both the 2002 and 2007 surveys among adults with chronic disease-related functional limitations were estimated. Prevalence estimates were age standardized to the 2000 U.S. population. Sampling weights and design variables of the NHIS were used to calculate accurate standard errors. Chi-square tests of independence were used to compare the prevalence of use in 2002–2007. Statistical analysis system-callable SUDAAN version 10.0.1 (Research Triangle Park, NC) was used for all analyses to account for the complex survey design of the NHIS. All statistical inferences were based on conventional α levels of p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001.

Results

Characteristics of study population

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the study population in 2002 and 2007. Significant differences between 2007 and 2002 were found by age, education, and income. Compared to adults with chronic disease-related functional limitations in 2002, those in 2007 were older, had a higher level of educational attainment, and had a higher family income.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Adults with Chronic Disease-Related Functional Limitations in 2002 and 2007

|

2002 (n = 9313, N= 58,550) |

2007 (n = 7014, N= 64,397) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SE | n | N | % | SE | n | N | |

| Age, yrs.* | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 5.1 | 0.3 | 346 | 2964 | 4.5 | 0.4 | 242 | 2895 |

| 25–44 | 24.0 | 0.6 | 2143 | 14,057 | 21.7 | 0.6 | 1403 | 13,981 |

| 45–64 | 38.2 | 0.6 | 3371 | 22,392 | 41.3 | 0.7 | 2742 | 26,577 |

| ≥ 65 | 32.7 | 0.6 | 3453 | 19,137 | 32.5 | 0.8 | 2627 | 20,945 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 40.8 | 0.7 | 3387 | 23,860 | 41.7 | 0.7 | 2663 | 26,869 |

| Female | 59.2 | 0.7 | 5926 | 34,690 | 58.3 | 0.7 | 4351 | 37,528 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 7.4 | 0.3 | 1064 | 4325 | 8.4 | 0.5 | 817 | 5380 |

| White non-Hispanic | 78.9 | 0.6 | 6769 | 46,198 | 77.1 | 0.7 | 4778 | 49,665 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 10.8 | 0.4 | 1252 | 6333 | 11.1 | 0.5 | 1151 | 7147 |

| Other non-Hispanic | 2.9 | 0.2 | 228 | 1694 | 3.4 | 0.3 | 268 | 2205 |

| Education** | ||||||||

| < High school | 22.4 | 0.5 | 2330 | 12,974 | 20.2 | 0.6 | 1617 | 12,933 |

| High school | 60.3 | 0.6 | 5390 | 34,950 | 59.6 | 0.8 | 4041 | 38,118 |

| ≥ College | 17.3 | 0.5 | 1503 | 10,048 | 20.1 | 0.7 | 1310 | 12,871 |

| Family incomea,* | ||||||||

| < $20,000 | 28.0 | 0.6 | 3514 | 16,392 | 24.2 | 0.7 | 2333 | 15,558 |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 23.0 | 0.5 | 2172 | 13,443 | 21.6 | 0.6 | 1547 | 13,927 |

| $35,000–$64,999 | 25.5 | 0.6 | 2060 | 14,904 | 26.4 | 0.7 | 1656 | 16,971 |

| ≥ $65,000 | 23.6 | 0.6 | 1567 | 13,811 | 27.9 | 0.8 | 1478 | 17,941 |

| Region | ||||||||

| Northeast | 18.3 | 0.6 | 1649 | 10,702 | 16.6 | 0.7 | 1177 | 10,668 |

| Midwest | 27.0 | 0.8 | 2409 | 15,803 | 26.3 | 0.9 | 1735 | 16,928 |

| South | 36.5 | 0.8 | 3373 | 21,350 | 35.6 | 1.0 | 2543 | 22,920 |

| West | 18.3 | 0.6 | 1882 | 10,695 | 21.6 | 0.8 | 1559 | 13,881 |

n, unweighted sample size; N, national estimate (in 1000s); %, weighted percentage; SE, standard error.

Imputed.

p < 0.01

p < 0.05.

Comparison of overall CAM use by ICF functional status between 2002 and 2007

Among adults with chronic disease-related functional limitations, the unadjusted and age-standardized prevalence of overall CAM use (defined as the 22 CAM therapies comparable between both survey years) was higher in 2007 than in 2002 (30.6% versus 26.9%, p < 0.001 and 34.4% versus 30.6%, p < 0.001, respectively) (Table 2). Adults with functional limitations that included changing and maintaining body position experienced a significant increase in CAM use between 2002 and 2007 (31.1%–35.0%, p < 0.01). Adults who had functional limitations that included difficulties with walking and moving around had the lowest prevalence estimate of CAM use in both 2002 (27.9%) and 2007 (26.9%), while those with limitations that included the other two ICF classifications were similar users of CAM.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Age-Standardized Prevalence with 95% CI of Overall CAM Use in the Past 12 Months Among Adults Aged 18 Years or Older with Chronic Disease-Related Functional Limitations, by ICF Functional Status in 2002 and 2007

| Unadjusted | Age-standardized | |

|---|---|---|

| Changing and maintaining body position | ||

| 2002 (n = 8256) | 27.3 (26.1–28.5) | 31.1 (29.6–32.6) |

| 2007 (n = 6274) | 30.9 (29.5–32.4)* | 35.0 (33.2–36.8)** |

| Carrying, moving, and handling objects | ||

| 2002 (n = 5200) | 28.2 (26.6–29.8) | 33.3 (31.2–35.5) |

| 2007 (n = 3907) | 30.9 (29.0–32.8)*** | 34.9 (32.3–37.6) |

| Walking and moving around | ||

| 2002 (n = 5148) | 23.6 (22.3–25.0) | 27.9 (26.1–29.8) |

| 2007 (n = 4130) | 24.9 (23.4–26.6) | 26.9 (24.5–29.4) |

| Recreation and leisure | ||

| 2002 (n = 2938) | 27.7 (25.8–29.8) | 34.1 (31.0–37.2) |

| 2007 (n = 2482) | 29.7 (27.5–32.1) | 34.2 (31.2–37.3) |

| Overall | ||

| 2002 (n = 9307) | 26.9 (25.8–28.0) | 30.6 (29.2–31.9) |

| 2007 (n = 7011) | 30.6 (29.2–32.0)* | 34.4 (32.6–36.1)* |

CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; CI, confidence interval; ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health.

p < 0.001

p < 0.01

p < 0.05.

Comparison of 22 CAM therapies between 2002 and 2007

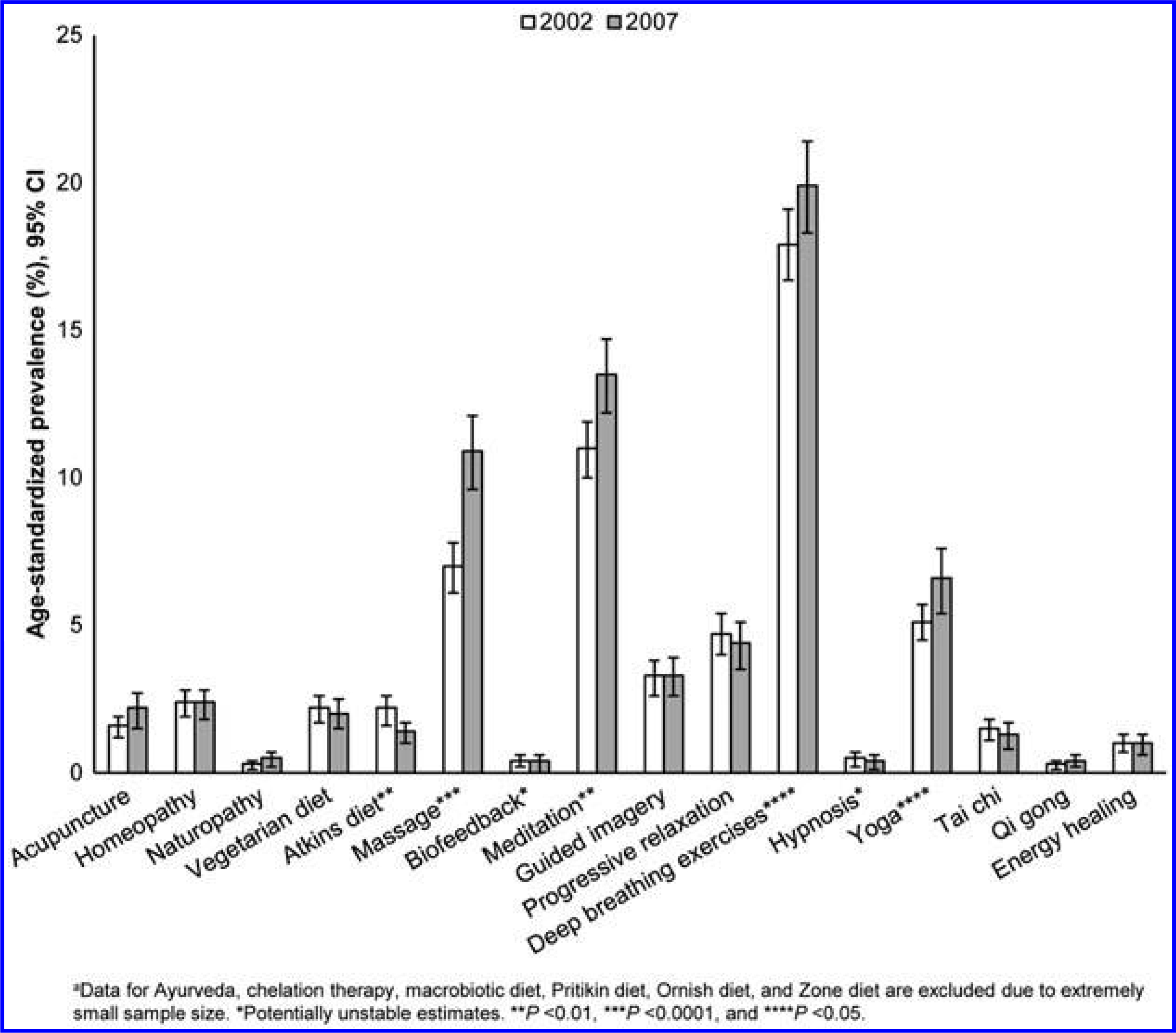

After age adjustment, deep breathing exercises, the most prevalent of the 22 CAM therapies, experienced a significant increase between 2002 and 2007 (from 17.9% to 19.9%, p < 0.05) (Fig. 1). Massage and two other mind–body therapies (i.e., meditation and yoga) also increased significantly from 2002 and 2007 (7.0%–10.9%, p < 0.0001; 11.0%–13.5%, p < 0.01; and 5.1%–6.6%, p < 0.05, respectively). The commercial diet-based therapy, Atkins, decreased significantly from 2002 and 2007 (2.2%–1.4%, p < 0.01). The age-standardized prevalence of acupuncture, homeopathy, naturopathy, vegetarian diet, biofeedback, guided imagery, progressive relaxation, hypnosis, t’ai chi, qigong, and energy healing was similar among adults with functional limitations between 2002 and 2007. However, it was not possible to make reliable statistical comparisons for Ayurveda, chelation therapy, and the four remaining diet-based therapies (i.e., macrobiotic diet, Pritikin diet, Ornish diet, and Zone diet) due to small sample sizes.

FIG. 1.

Age-standardized prevalence with 95% confidence interval (CI) of use of 16 complementary and alternative medicine therapiesa in the past 12 months among adults aged 18 years or older with chronic disease-related functional limitations in 2002 and 2007.

Discussion

In this large, nationally representative study, there were several interesting findings. First, adults with chronic disease-related limitations that included difficulties with changing and maintaining body position had a significant increase in overall CAM use between 2002 and 2007. Notably, it was found that those with functional limitations that included difficulties with walking or moving around had the lowest prevalence of overall CAM use. Second, the use of two mind–body therapies (i.e., deep breathing exercises and meditation) was the most prevalent in both 2002 and 2007, and increased significantly during this time period. Third, the use of massage therapy was the only non-mind–body therapy that increased significantly between 2002 and 2007. Finally, use of the commercial Atkins diet experienced a significant decrease between 2002 and 2007.

These results are similar to the findings of other researchers. Barnes et al.3 reported similar, though less prevalent, increases in use of mind–body therapies among the general U.S. adult population from 2002 to 2007, such as deep breathing exercises (11.6%–12.7%; p < 0.01) and meditation (7.6%–9.4%; p < 0.001). In addition, these researchers found that the use of acupuncture, massage, naturopathy, and yoga increased significantly during this time period as well.3 Similarly, the present authors also found that use of these four CAM therapies increased during this time period among adults with functional limitations. However, the use of acupuncture (1.6%–2.2%; p = 0.1037) and naturopathy (0.3%–0.5%; p = 0.2184) did not experience similar increases. It is not surprising that this study’s CAM estimates are higher than those of the general population, given that adults with functional limitations and chronic disease have been shown to be frequent users of CAM (e.g., treatment, pain management, disease prevention, and general well-being).23–27,33–35 In a previous study,27 it was found that adults with functional limitations used massage therapy most often for treatment of the condition underlying their limitation, whereas relaxation techniques (e.g., deep breathing exercises, meditation, and progressive relaxation) were used most for noncondition purposes.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is one of two studies to examine use of CAM therapies by functional status as defined by the ICF.29 Using 1999 NHIS data, Hendershot33 examined the use of CAM, with and without prayer, among adults with ICF-defined mobility limitations. Consistent with the present study’s findings, Hendershot found that adults with mobility limitations that included difficulties with changing and maintaining body position and carrying, moving, and handling objects had higher prevalence estimates of use of CAM without prayer than those with difficulties with walking and moving around. However, when prayer was examined with or without other CAM, the prevalence estimates of CAM use were similar regardless of ICF mobility function. Further comparisons between the two studies were not possible as the present study did not examine the use of prayer. On the other hand, this study also examined difficulties with recreation and leisure and found the use of CAM among this population to be the same as those with changing and maintaining body position and carrying, moving, and handling objects difficulties.

Adults with chronic disease-related functional limitations may use CAM for a variety of reasons, such as to augment conventional medical treatments, to manage the side-effects of medical treatments and disease symptoms, and to enhance general well-being. For example, manipulative and body-based therapies, such as massage therapy, have been proven to be effective CAM therapies for the treatment of chronic back pain17,18 and for oncology patients experiencing anxiety or pain.36,37 Among patients with cancer, mind–body therapies (e.g., meditation, deep breathing exercises, and yoga) can reduce anxiety, chronic pain, and mood disturbance.37 In addition, acupuncture has demonstrated effectiveness in the reduction of pain among those with cancer, fibromyalgia, and chronic low-back pain,17,18,37,38 and the amount of pain medication required among oncology patients.37 Thus, health care organizations have incorporated CAM therapies with proven benefits into their respective clinical practice guidelines.18,36–38 This, to a large extent, may explain the relatively large percentage increases observed between 2002 and 2007 for massage therapy (55.7%), acupuncture (37.5%), yoga (29.4%), meditation (22.7%), and deep breathing exercises (11.2%).

This study has some limitations. First, data were based on self-reports and are subject to recall bias. Second, it was only possible to assess 22 CAM therapies that were common between the 2002 and 2007 NHIS surveys. Finally, because NHIS is cross-sectional, it was not possible to determine whether CAM use occurred before or after adults experienced functional difficulty.

This study has several strengths. It is based on a large, nationally representative survey of the community-dwelling U.S. adult population. In addition, this study adds to the literature by examining CAM use by ICF-defined categories.

Conclusions

A high prevalence of overall CAM use was found among adults with chronic disease-related functional limitations. In particular, use of mind–body therapies was prevalent among this population. Between 2002 and 2007, advancements in the evidence base have proven the safety and efficacy of several CAM therapies for treatment use among specific chronic disease populations, and thus, they have been integrated into current clinical guidelines. However, adults with chronic-disease-related functional limitations may use CAM therapies that have not been proven safe and effective. Thus, health care environments that encourage an open communication of CAM use and its assessment are essential. Further examination of the socio-economic factors and other determinants of CAM use among ICF-defined subpopulations may provide useful information to inform public health messaging on the safe and efficacious use of CAM therapies.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA 1998;280:1569–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States: Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. NEJM 1993;328:246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. National Health Statistics Report 2008; 12:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tindle HA, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Eisenberg DM. Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997–2002. Altern Ther Health Med 2005;11:42–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data 2004;343:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, Bloom B. Costs of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and frequency of visits to CAM practitioners: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report 2009;18:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenberg DM, Cohen MH, Hrbek A, et al. Credentialing complementary and alternative medical providers. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolsko PM, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, et al. Insurance coverage, medical conditions, and visits to alternative medicine providers: Results of a national survey. Arch Int Med 2002; 162:281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lafferty WE, Tyree PT, Bellas AS, et al. Insurance coverage and subsequent utilization of complementary and alternative medicine providers. Am J Manag Care 2006;12:397–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steyer TE, Freed GL, Lantz PM. Medicaid reimbursement for alternative therapies. Altern Ther Health Med 2002;8:84–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barzansky B, Etzel SI. Educational programs in US medical schools, 2002–2003. JAMA 2003;290:1190–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verhoef M, Brundin-Mather R, Jones A, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in undergraduate medical education. Associate deans’ perspectives. Can Fam Physician 2004;50:847–849, 853–845. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maizes V, Silverman H, Lebensohn P, et al. The integrative family medicine program: An innovation in residency education. Acad Med 2006;81:583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiflett SC. Overview of complementary therapies in physical medicine and rehabilitation. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 1999;10:521–529, vii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gage H, Storey L, McDowell C, et al. Integrated care: Utilisation of complementary and alternative medicine within a conventional cancer treatment centre. Complement Ther Med 2009;17:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arthur HM, Patterson C, Stone JA. The role of complementary and alternative therapies in cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic evaluation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2006;13:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou R, Huffman LH. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: A review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2007;147: 492–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:478–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Washington, DC: US: Department of Health and Human Services, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humpel N, Jones SC. Gaining insight into the what, why and where of complementary and alternative medicine use by cancer patients and survivors. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2006;15:362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chevarley FM, Thierry JM, Gill CJ, et al. Health, preventive health care, and health care access among women with disabilities in the 1994–1995 National Health Interview Survey, Supplement on Disability. Womens Health Issues 2006;16:297–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livermore G, Stapleton DC, O’Toole M. Health care costs are a key driver of growth in federal and state assistance to working-age people with disabilities. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:1664–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okoro CA, Zhao G, Li C, Balluz LS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among US adults with and without functional limitation. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saydah SH, Eberhardt MS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among adults with chronic diseases: United States 2002. J Altern Complement Med 2006;12: 805–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krauss HH, Godfrey C, Kirk J, Eisenberg DM. Alternative health care: Its use by individuals with physical disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:1440–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlson MJ, Krahn G. Use of complementary and alternative medicine practitioners by people with physical disabilities: Estimates from a National US Survey. Disabil Rehabil 2006; 28:505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okoro CA, Zhao G, Li C, Balluz LS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among USA adults with functional limitations: For treatment or general use? Complement Ther Med 2011;19:208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quandt SA, Chen H, Grzywacz JG, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by persons with arthritis: Results of the National Health Interview Survey. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:748–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey. About the National Health Interview Survey. Online document at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm Accessed January 6, 2012.

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey. Methods. Online document at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/methods.htm Accessed January 6, 2012.

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey. Questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation 1997 to the present. Online document at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/quest_data_related_1997_forward.htm Accessed January 6, 2012.

- 33.Hendershot GE. Mobility limitations and complementary and alternative medicine: Are people with disabilities more likely to pray? Am J Public Health 2003;93:1079–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grzywacz JG, Suerken CK, Quandt SA, et al. Older adults’ use of complementary and alternative medicine for mental health: Findings from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J Altern Complement Med 2006;12: 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wainapel SF, Thomas AD, Kahan BS. Use of alternative therapies by rehabilitation outpatients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:1003–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deng GE, Frenkel M, Cohen L, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for integrative oncology: Complementary therapies and botanicals. J Soc Integr Oncol 2009; 7:85–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cassileth BR, Deng GE, Gomez JE, et al. Complementary therapies and integrative oncology in lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, 2nd ed. Chest 2007;132:340S–354S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Guideline Summary. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome in adults. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. Online document at: www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=14869&search=fibromyalgia Accessed January 6, 2012. [Google Scholar]