Abstract

Aldosterone production is physiologically under the control of circulating potassium and angiotensin II as well as adrenocorticotropic hormone and other secretagogues such as serotonin. The adrenal’s capacity to produce aldosterone relies heavily on the expression of a single enzyme, aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2). This enzyme carries out the final reactions in the synthesis of aldosterone and is expressed almost solely in the adrenal zona glomerulosa. From a disease standpoint, primary aldosteronism (PA) is the most common of all adrenal disorders. PA results from renin-independent adrenal expression of CYP11B2 and production of aldosterone. The major causes of PA are adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas (APA) and adrenal idiopathic hyperaldosteronism. Our understanding of the genetic causes of APA has significantly improved through comprehensive genetic profiling with next-generation sequencing. Whole-exome sequencing has led to the discovery of mutations in six genes that cause renin-independent aldosterone production and thus PA. To facilitate broad-based prospective and retrospective studies of APA, recent technologic advancements have allowed the determination of tumor mutation status using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections. This approach has the advantages of providing ready access to archival samples and allowing CYP11B2 immunohistochemistry-guided capture of the exact tissue responsible for inappropriate aldosterone synthesis. Herein we review the methods and approaches that facilitate the use of adrenal FFPE material for DNA capture, sequencing, and mutation determination.

Keywords: primary aldosteronism, CYP11B2, somatic mutation, immunohistochemistry, next-generation sequencing

Introduction

Technologic advances in genetic analysis have provided us a better understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of endocrine-related tumors. Aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA) is one of the major subtypes of primary aldosteronism (PA), the most common cause of endocrine-related hypertension. The application of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has resulted in the identification of disease-causing mutations in APA and familial PA. Aldosterone-driver mutations can occur in genes encoding membrane ion channels or pumps (1–9). Thus far, APA have been found with mutations in KCNJ5 (1), ATP1A1 (2, 4), ATP2B3 (2), CACNA1D (3, 4), CACNA1H (9), and CLCN2 (8) (aldosterone-driver mutations). These mutations cause excess aldosterone production by raising intracellular calcium levels which leads to enhanced CYP11B2 (aldosterone synthase) expression and renin-independent aldosterone production (10). Like other adrenocortical tumors, activating mutations in CTNNB1 gene (encoding β-catenin) have also been documented in a subset of APA (11–14) but the mechanism of CTNNB1 mutation activation of aldosterone production remains to be clearly defined. So far more than 90 APA somatic mutations have been reported ( Table 1 ). Of note, only part of the previously reported somatic mutations has been functionally tested so far. To assess the pathologic role of these mutations, it would be ideal to perform cell-based studies for each mutation. In addition to tumor somatic mutations, PA aldosterone production may be regulated by hormones that include adrenocorticotropic hormone, serotonin, or luteinizing hormone (37–44).

Table 1.

Previously reported somatic mutations in aldosterone-producing adenomas.

| Gene | Somatic Mutations | |

|---|---|---|

| KCNJ5 | c.343C>T (p.R115W) (15) | c.445_446insTGG (p.T149delinsMA) (49) |

| c.376T>C (p.W126R) (16) | c.447_448insATT (p.T149delinsTI) (14) | |

| c.414_425dupGCTTTCCTGTTC (p.A139_F142dup) (17) | c.450_451insATG (p.I150_G151insM) (13) | |

| c.420C>G (p.F140L) (14)a | c.451G>A (p.G151R) (1) | |

| c.433_434insCCATTG (p.I144_E145insAI) (13) | c.451G>C (p.G151R) (24) | |

| c.433G>C (p.E145Q) (18) | (p.G151_Y152del)* (25) | |

| c.433G>A (p.E145K) (4) | c.457_492dupG_G (p.G153_G164dup) (20) | |

| c.432_439delTGAGACCGinsCA (p.E145_E147delinsK) (19) | c.461T>G (p.F154C) (13) | |

| c.439G>C and c.448_449insCAACAACCA (p.E147Q_T149_I150insTTT) (20) | c.467_469delTCA (p.I157del) (26) | |

| c.443C>T (p.T148I) (21)b | c.470_471delinsAA (p.I157K) (13) | |

| c.445_446insGAA (p.T148_T149insR) (22) | (p.I157_E159del)* (25) | |

| c.446insAAC (p.T149_I150insT) (23) | c.472A>G (p.T158A) (27) | |

| c.445A>T (p.T149S) (21) | c.503T>G (p.L168R) (1) | |

| (p.G184E)* (25) | ||

| c.737A>G (p.E246G) (15) | ||

| ATP1A1 | c.295G>A (p.G99R) (16) | c.2874_2882delCTTTGAAGA (p.F959_E961del) (29) |

| c.299_313delTCTCAATGTTACTGT (p.F100_L104del) (2) | c.2877_2882delTGAAGA (p.F959_E961delinsL) (28) | |

| c.304_309delATGTTA (p.M102_L103del) (28) | c.2878_2895delGAAGAGACAGCCCTGGCTinsGCCCTGGTT (p.E960_A965delinsALV) (48) | |

| c.306_317delGTTACTGTGGAT (p.M102_I106delinsW) (28) | c.2877_2888delTGAAGAGACAGC (p.E960_A963del) (29) | |

| c.308_313delTACTGT (p.L103_L104del) (28) | c.2878_2887delGAAGAGACAGinsT (p.E960_A963delinsS) (4) | |

| c.311T>G (p.L104R) (2) | c.2879_2890delAAGAGACAGCCC (p.E960_L964delinsV) (28) | |

| c.995T>G (p.V332G) (2) | c.2878_2892delGAAGAGACAGCCCTGinsGCCGTG (p.E960_L964delinsAV) (14) | |

| c.2864_2878delTATTTGGCCTCTTTG (p.I955_E960delinsK) (49) | ||

| c. 2867_2882delTTGGCCTCTTTGAAGAinsG (p.F956_E961delinsW) (28) | ||

| ATP2B3 | c.367G>C (p.G123R) (30) | c.1273_1278delCTGGTC (p.L425_V426del) (2) |

| c.1228T>G (p.Y410D) (31) | c.1277_1282delTCGTGG (p.V426_V427del) (2) | |

| c.1264_1278delGTCACTGTGCTGGTCinsAGCACACTC (p.V422_V426delinsSTL) (22) | c.1276_1287delGTCGTGGCTGTC (p.V426_V429del) (28) | |

| c.1264_1275delGTCACTGTGCTGinsATCACT (p.V422_L425delinsIT) (14) | c.1276_1298insGACA_delTCGTGGCTGTCCCAGAGGGCCT (p.V426G_V427Q_A428_L433del) (13) | |

| c.1269_1274delTGTGCT (p.V424_L425del) (32) | c.1279_1284delGTGGCT (p.V427_A428del) (33) | |

| c.1270_1275delGTGCTG (p.V424_L425del) (55) | c.1281_1286delGGCTGT (p.A428_V429del) (34) | |

| c.1272_1277delGCTGGT (p.L425_V426del) (2) | ||

| CACNA1D | c.776T>A (p.V259D) (4) | c.2906C>T (p.S969L) (48) |

| c.776T>G (p.V259G) (14) | c.2936T>A (p.V979D) (55) | |

| c.926T>C (p.V309A) (49) | c.2943G>C (p.V981N) (55) | |

| c.1201C>G (p.V401L) (28) | c.2968C>G (p.R990G) (49) | |

| c.1207G>C [p.G403R (exon8A)] (3, 4) | c.2969G>A (p.R990H) (4) | |

| c.1207G>C [p.G403R (exon8B)] (3)** | c.2978G>C (p.R993T) (49) | |

| c.1229C>T (p.S410L) (30) | c.2978G>T (p.R993M) (29) | |

| c.1856G>C (p.R619P) (49) | c.2992_2993GC>AT (p.A998I) (55) | |

| c.1955C>T (p.S652L) (55) | c.2993C>T (p.A998V) (55) | |

| c.1964T>C (p.L655P) (55) | c.3019T>C (p.C1007R) (49) | |

| c.2182G>A (p.V728I) (20) | c.3044T>G (p.I1015S) (49) | |

| c.2222A>G (p.Y741C) (55) | c.3044T>C (p.I1015T) (58) | |

| c.2239T>G (p.F747V) (3) | c.3451G>T (p.V1151F) (55) | |

| c.2239T>C (p.F747L) (4) | c.3452T>C (p.V1151A) (29) | |

| c.2241C>G (p.F747L) (4) | c.3455T>A (p.I1152N) (55) | |

| c.2240T>G (p.F747C) (56) | c.3458T>G (p.V1153G) (35) | |

| c.2240T>C (p.F747S) (29)c | c.4007C>G (p.P1336R) (4) | |

| c.2250C>G (p.I750M) (3, 4) | c.4012G>A (p.V1338M) (3) | |

| c.2248A>T (p.I750F) (55) | c.4062G>A (p.M1354I) (4) | |

| c.2261A>G (p.N754S) (29) | ||

| CACNA1H | c.4289T>C (p.I1430T) (9) | |

| CLCN2 | c.71G>A (p.G24D) (8) | |

| c.64-2_74del (36) | ||

a-cAssociated with another somatic mutation (aKCNJ5 p.G151R; bKCNJ5 p.T149S; cCACNA1D p.N754S). * Base change information was not provided in the original article. For the CACNA1D mutations, amino acid substitutions are described based on the reference sequence NM_001128839 otherwise noted (**NM_000720 for the mutation in exon 8B). Mutations that are covered by the primer sets in Table 2 are highlighted in blue.

Since the development of specific antibodies against human CYP11B2, which is required for aldosterone biosynthesis, CYP11B2 immunohistochemistry (IHC) has played an important role in defining the histopathologic characteristics of adrenals from patients with PA (45, 46). CYP11B2 IHC has revealed diversities in the histopathology of adrenals from patients with PA, including APA (CYP11B2-expressing adrenocortical adenoma) and adrenals with small CYP11B2-expressing cell nests, called aldosterone-producing cell clusters (APCCs) (45) or aldosterone-producing micronodules (APMs) (47). Advanced sequencing methods combined with CYP11B2 IHC have significantly improved the detection rate of somatic mutations in APA (14, 48, 49). CYP11B2 IHC-guided targeted NGS has also allowed the detection of aldosterone-driver mutations in APCCs (APMs) using small amounts of DNA (50–52). Herein, we provide an overview of recent advances in the genetic analysis of APA and introduce a streamlined sequencing approach using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue material.

Importance of CYP11B2 IHC and Targeted DNA Capture

Development of specific antibodies against human CYP11B2 has allowed detection of the source of pathologic aldosterone production in the resected adrenal tissue (45, 46). Unique characteristics of adrenals from patient with PA have been documented by CYP11B2 IHC. Importantly, adrenal tumors detected by cross-sectional imaging study are not always the cause of aldosterone excess even when adrenal vein sampling lateralizes autonomous aldosterone production to the tumor side (53). In such cases, APA can be below the detection limit of imaging studies and/or imaging-detected tumors can be non-functioning adrenocortical adenomas (CYP11B2-negative tumors by IHC). Cases with multiple APAs within one adrenal have also been documented (14, 48, 49, 54).

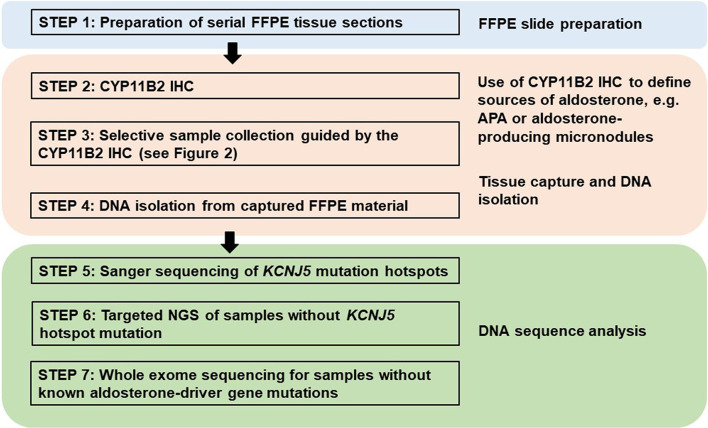

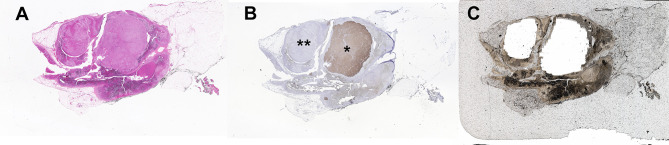

Traditionally, DNA and RNA have been isolated from snap frozen tumor pieces obtained during pathologic gross dissection at the time of adrenalectomy. Mutational analysis has subsequently been performed without consideration of CYP11B2 expression prior to sequencing. In the largest mutation prevalence study using this conventional approach, aldosterone-driver somatic mutations were detected in 54% of 474 adrenal tumors from PA patients (55). Considering the aforementioned diversities in the histology of PA, this approach could negatively affect the accuracy of mutational analysis. As such, we recently developed an advanced molecular profiling method using selective DNA isolation from FFPE sections based on CYP11B2 IHC, followed by NGS (14, 56). The step-by-step sequencing method using the CYP11B2 IHC-guided approach is shown in Figure 1 . Many laboratories, including ours, use a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for human CYP11B2 that was produced and characterized by Dr. Celso Gomez-Sanchez (46). This antibody is commercially available from Millipore Sigma (MABS1251, RRID: AB_2783793), making it useful for both research and pathologic diagnosis purposes. As is needed for most antibodies, laboratory testing for individual in-house protocols should be done to optimize specificity and sensitivity for CYP11B2 detection. Initial protocol testing is particularly important due to the variable CYP11B2 expression seen between APAs. The scanned slide images of adrenal tumor tissue from a PA patient are shown in Figure 2 . The adrenal contains two distinct adrenocortical tumors (an APA and a CYP11B2-negative tumor) which exist close to each other. This example highlights the importance of targeted DNA capture method for accurate mutation analysis. Importantly, past studies demonstrated that no aldosterone-driver mutation was detected in CYP11B2-negative adrenocortical tumors from PA patients (49, 57).

Figure 1.

Proposed method for DNA mutation analysis using excised adrenal tissue sections from patients with primary aldosteronism. This approach uses CYP11B2 immunohistochemistry (IHC) to define the source of aldosterone for DNA capture in FFPE tissue sections. Captured DNA is then used for Sanger or gene-targeted deep sequencing to detect known and/or novel drivers of aldosterone production.

Figure 2.

Example of a multinodular adrenal sample from a patient with primary aldosteronism that illustrates the benefit of CYP11B2 IHC-guided DNA capture. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining, (B) CYP11B2 immunohistochemistry; *, aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA); **, CYP11B2-negative tumor, (C) Post-captured unstained FFPE adrenal tissue section. For DNA isolation, an APA and a CYP11B2-negative tumor were selectively scraped based on the results of CYP11B2 immunohistochemistry.

Using this CYP11B2 IHC-guided approach, aldosterone-driver mutations have been identified in 88-96% of APAs (14, 48, 49). A recent study demonstrated a better mutation detection rate using CYP11B2-IHC guided sequencing (94%) as compared to the authors’ previous use of conventional tumor tissue approaches (71%) (58).

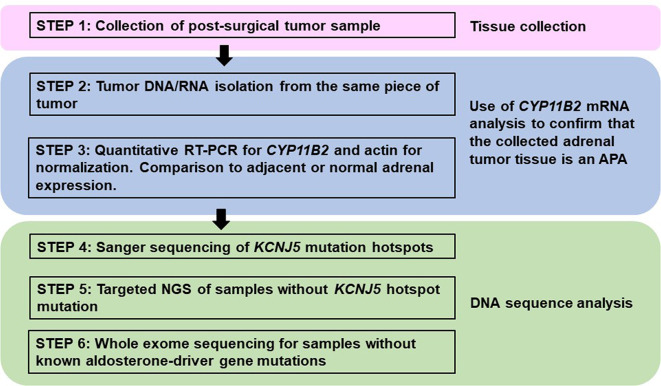

For the laboratories using traditional material, i.e., DNA/RNA from macro-dissected snap frozen tumor pieces, confirmation of CYP11B2 mRNA expression by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) prior to sequencing could also improve the mutation detection rate. A proposed method for mutational analysis using banked snap frozen material is shown in Figure 3 .

Figure 3.

Proposed method for processing fresh or frozen adrenal tumor tissue from patients with primary aldosteronism for mutational analysis. This approach varies from FFPE processing (Figure 1) by the method of tissue collection and the need to use CYP11B2 mRNA detection for confirmation of APA status. However, mutational analysis is similar using Sanger and/or next-generation sequencing to detect known and/or novel drivers of aldosterone production.

Defining Somatic Mutations in Aldosterone-Producing Lesions

Sanger Sequencing

Traditional direct Sanger sequencing has been widely used for the mutational analysis of APA. As new APA-related genes have continuously been identified, it is challenging to perform Sanger sequencing for the screening of multiple genes – particularly for genes like CACNA1D, which have a large coding region with dispersed mutation hotspot areas. Targeted NGS is rapidly becoming the preferred method due to its high sensitivity and ability to utilize small amounts of DNA; however, Sanger sequencing is still an attractive method considering the high per sample cost of NGS. As the prevalence of KCNJ5 hotspot mutations in APA is relatively high, one option to decrease sample throughput is screening for KCNJ5 mutation hotspots using Sanger sequencing, followed by targeted NGS of KCNJ5 mutation-negative samples (29, 48) ( Figure 1 ). This approach significantly reduces cost and can also be applied to material isolated from traditional snap frozen tissue ( Figure 3 ). For researchers without available NGS to screen entire coding regions, targeted Sanger sequencing that covers the majority of known aldosterone-driver mutations can be done in a systematic manner. Based on the APA mutation prevalence from our previous study (14), the use of five primer pairs (one for the KCNJ5, one for ATP1A1, one for ATP2B3, and two for CACNA1D, Table 2 ) appear to be able to identify over 70% of mutations by direct Sanger sequencing in a Caucasian American cohort. Special consideration is required for primer design when using genomic DNA (gDNA) from FFPE as a template, since FFPE-extracted DNA can be heavily degraded and fragmented. The authors recommend designing primer sets that target the amplicon size below 250 base pairs (bp) if possible.

Table 2.

PCR primer sets for aldosterone-driver mutation hotspots.

| Gene | Exon | Primer Sequences | Amplicon Size (bp) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCNJ5 | 2 | Forward | GGACCATGTTGGCGACCAAGAGTG | 211 | (21) |

| Reverse | GACAAACATGCACCCCACCATGAAG | ||||

| ATP1A1 | 4 | Forward | ATTAACATCTGCTCGTGCAGCTGAG | 227 | |

| Reverse | CCATATGCTGAATTACAGAACTCAC | ||||

| ATP2B3 | 8 | Forward | TGTCTGCCATCACCGTCATCATC | 255 | (14) |

| Reverse | CCCAGTTTCCGAGTCTGTAAACAG | ||||

| CACNA1D | 8A | Forward | CCCACTCCTATGAGACCATC | 190 | |

| Reverse | TCTTGGCAACTGTCCTCAGG | ||||

| 16 | Forward | GGTGTGTGGCGTTGCCATTG | 253 | (29) | |

| Reverse | AACTGTTGCAGGGCTCCCA | ||||

Next-Generation Sequencing

NGS has rapidly become the standard approach for comprehensive molecular profiling of human tumors due to its ability to generate sequence-level genetic data simultaneously for tens, hundreds, or even thousands of genes. Although a variety of NGS methods and platforms exist, there are two broad approaches: amplicon-based and hybridization capture-based ( Table 3 ). Amplicon-based approaches utilize multiplex PCR reactions to amplify genomic regions of interest, while hybridization capture-based methods utilize biotinylated oligonucleotide baits to pull down target regions from pools of sheared gDNA. In general, amplicon-based methods are preferred for targeted sequencing of small numbers of genomic regions or when available input DNA for NGS library preparation is very low – particularly for FFPE samples – while hybridization capture-based approaches are favored for analyzing a large number of genomic regions [e.g., whole-exome sequencing (WES)] when ample input DNA is available. These and other differences between the NGS approaches inform how they may be best utilized for molecular profiling of aldosterone-producing lesions using FFPE tissue ( Figure 1 ).

Table 3.

Comparison of NGS approaches for molecular profiling of aldosterone-producing adrenal cortical lesions.

| Amplicon-based | Hybridization Capture-based | |

|---|---|---|

| Enrichment method | Multiplex PCR | Biotinylated oligonucleotide baits |

| Input DNA | Less | More |

| # of genomic targets | Fewer | More |

| Experimental time | Less | More |

| Cost per sample | Lower* | Higher* |

| Application(s) | Targeted sequencing | Targeted sequencing or WES |

*Depends on depth of sequencing and # of genomic targets.

WES, whole-exome sequencing.

Given the relatively limited number of established aldosterone-driver mutations – coupled with the fact that most of these mutations occur at specific hotspot regions within the affected genes – targeted amplicon-based NGS is ideal for characterizing FFPE APA samples. As mentioned earlier, recent studies utilizing this approach have identified somatic aldosterone-driver mutations in the vast majority of APA. In addition to the ability to interrogate multiple genomic regions simultaneously, one of the important advantages of NGS over Sanger sequencing is improved sensitivity for detecting genetic variants. This is particularly important for detecting somatic mutations in microscopic lesions (i.e., APCC/APM), for which the expected allelic variant fraction may be less than 20% (depending on the purity of the isolated tissue for sequencing). Application of targeted amplicon-based NGS to APCC in normal adrenal glands and from patients with adrenal idiopathic hyperaldosteronism has identified somatic aldosterone-driver mutations in 34-58% of these lesions (50–52). For aldosterone-producing lesions that are mutation-negative by targeted amplicon-based NGS, hybridization capture-based WES of CYP11B2 IHC-guided FFPE tissue may identify novel aldosterone-driver mutations (9, 36). Finally, despite several clear advantages of NGS-based molecular profiling, application of these approaches to FFPE tissue is potentially limited by FFPE-associated DNA degradation (e.g., increased genomic fragmentation, artifactual nucleotide deamination) and technical issues (e.g., PCR amplification bias, sequencing error). Emerging NGS methods, including the use of unique molecular identifiers (UMI; as known as “molecular barcodes”), and novel NGS technologies may begin to address some of these limitations and will continue to revolutionize genomic characterization of human tumors, including aldosterone-producing lesions.

Conclusions

Recent advances in sequencing technology have significantly accelerated PA research to elucidate its molecular pathogenesis. Unique histologic characteristics of adrenals from patients with PA require special attention to tumor CYP11B2 expression for accurate somatic mutation identification. The streamlined approach using CYP11B2 IHC-guided DNA capture combined with NGS appears to be a preferred method for mutational analysis of adrenals from patients with PA. The use of this CYP11B2 IHC-guided sequencing approach in a large prospective cohort will allow us to accurately determine APA mutation prevalence as well as genotype-phenotype correlations.

Author Contributions

KN and WR conceived the idea of this review article. KN and AU drafted the manuscript. WR reviewed the manuscript and made edits on the contents. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (DK106618 and DK043140) to WR. KN is supported by the Japan Heart Foundation Research Grant.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Amy R. Blinder for her editorial assistance.

References

- 1. Choi M, Scholl UI, Yue P, Bjorklund P, Zhao B, Nelson-Williams C, et al. K+ Channel Mutations in Adrenal Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas and Hereditary Hypertension. Science (2011) 331:768–72. 10.1126/science.1198785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beuschlein F, Boulkroun S, Osswald A, Wieland T, Nielsen HN, Lichtenauer UD, et al. Somatic Mutations in ATP1A1 and ATP2B3 Lead to Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas and Secondary Hypertension. Nat Genet (2013) 45:440–4, 444e1-2. 10.1038/ng.2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scholl UI, Goh G, Stolting G, de Oliveira RC, Choi M, Overton JD, et al. Somatic and Germline CACNA1D Calcium Channel Mutations in Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas and Primary Aldosteronism. Nat Genet (2013) 45:1050–4. 10.1038/ng.2695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Azizan EA, Poulsen H, Tuluc P, Zhou J, Clausen MV, Lieb A, et al. Somatic Mutations in ATP1A1 and CACNA1D Underlie a Common Subtype of Adrenal Hypertension. Nat Genet (2013) 45:1055–60. 10.1038/ng.2716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scholl UI, Stolting G, Nelson-Williams C, Vichot AA, Choi M, Loring E, et al. Recurrent Gain of Function Mutation in Calcium Channel CACNA1H Causes Early-Onset Hypertension With Primary Aldosteronism. Elife (2015) 4:e06315. 10.7554/eLife.06315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scholl UI, Stolting G, Schewe J, Thiel A, Tan H, Nelson-Williams C, et al. CLCN2 Chloride Channel Mutations in Familial Hyperaldosteronism Type II. Nat Genet (2018) 50:349–54. 10.1038/s41588-018-0048-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fernandes-Rosa FL, Daniil G, Orozco IJ, Goppner C, El Zein R, Jain V, et al. A Gain-of-Function Mutation in the CLCN2 Chloride Channel Gene Causes Primary Aldosteronism. Nat Genet (2018) 50:355–61. 10.1038/s41588-018-0053-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dutta RK, Arnesen T, Heie A, Walz M, Alesina P, Soderkvist P, et al. A Somatic Mutation in CLCN2 Identified in a Sporadic Aldosterone-Producing Adenoma. Eur J Endocrinol (2019) 181:K37–41. 10.1530/EJE-19-0377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nanba K, Blinder AR, Rege J, Hattangady NG, Else T, Liu CJ, et al. Somatic CACNA1H Mutation As a Cause of Aldosterone-Producing Adenoma. Hypertension (2020) 75:645–9. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fernandes-Rosa FL, Boulkroun S, Zennaro MC. Genetic and Genomic Mechanisms of Primary Aldosteronism. Trends Mol Med (2020) 26:819–32. 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akerstrom T, Maharjan R, Sven Willenberg H, Cupisti K, Ip J, Moser A, et al. Activating Mutations in CTNNB1 in Aldosterone Producing Adenomas. Sci Rep (2016) 6:19546. 10.1038/srep19546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu VC, Wang SM, Chueh SJ, Yang SY, Huang KH, Lin YH, et al. The Prevalence of CTNNB1 Mutations in Primary Aldosteronism and Consequences for Clinical Outcomes. Sci Rep (2017) 7:39121. 10.1038/srep39121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scholl UI, Healy JM, Thiel A, Fonseca AL, Brown TC, Kunstman JW, et al. Novel Somatic Mutations in Primary Hyperaldosteronism Are Related to the Clinical, Radiological and Pathological Phenotype. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (2015) 83:779–89. 10.1111/cen.12873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nanba K, Omata K, Else T, Beck PCC, Nanba AT, Turcu AF, et al. Targeted Molecular Characterization of Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas in White Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2018) 103:3869–76. 10.1210/jc.2018-01004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cheng CJ, Sung CC, Wu ST, Lin YC, Sytwu HK, Huang CL, et al. Novel KCNJ5 Mutations in Sporadic Aldosterone-Producing Adenoma Reduce Kir3.4 Membrane Abundance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2015) 100(1):E155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williams TA, Monticone S, Schack VR, Stindl J, Burrello J, Buffolo F, et al. Somatic ATP1A1, ATP2B3, and KCNJ5 Mutations in Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas. Hypertension (2014) 63(1):188–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hardege I, Xu S, Gordon RD, Thompson AJ, Figg N, Stowasser M, et al. Novel Insertion Mutation in KCNJ5 Channel Produces Constitutive Aldosterone Release From H295R Cell. Mol Endocrinol (2015) 29(10):1522–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Akerstrom T, Crona J, Delgado Verdugo A, Starker LF, Cupisti K, Willenberg HS, et al. Comprehensive Re-Sequencing of Adrenal Aldosterone Producing Lesions Reveal Three Somatic Mutations Near the KCNJ5 Potassium Channel Selectivity Filter. PloS One (2012) 7(7):e41926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zheng FF, Zhu LM, Zhou WL, Zhang Y, Li MY, Zhu YC, et al. A Novel Somatic Mutation 145-147deleteinsk in KCNJ5 Increases Aldosterone Production. J Hum Hypertens (2017) 31(11):756–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang B, Li X, Zhang X, Ma X, Chen L, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence and Characterization of Somatic Mutations in Chinese Aldosterone-Producing Adenoma Patients. Med (Baltimore) (2015) 94(16):e708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nanba K, Omata K, Tomlins SA, Giordano TJ, Hammer GD, Rainey WE, et al. Double Adrenocortical Adenomas Harboring Independent KCNJ5 and PRKACA Somatic Mutations. Eur J Endocrinol (2016) 175(2):K1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zheng FF, Zhu LM, Nie AF, Li XY, Lin JR, Zhang K, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Somatic Mutations in Chinese Patients With Aldosterone-Producing Adenoma. Hypertension (2015) 65(3):622–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuppusamy M, Caroccia B, Stindl J, Bandulik S, Lenzini L, Gioco F, et al. A Novel KCNJ5-Inst149 Somatic Mutation Close to, But Outside, the Selectivity Filter Causes Resistant Hypertension by Loss of Selectivity for Potassium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2014) 99(9):E1765–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taguchi R, Yamada M, Nakajima Y, Satoh T, Hashimoto K, Shibusawa N, et al. Expression and Mutations of KCNJ5 mRNA in Japanese Patients With Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2012) 97(4):1311–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kitamoto T, Omura M, Suematsu S, Saito J, Nishikawa T. KCNJ5 Mutation as a Predictor for Resolution of Hypertension After Surgical Treatment of Aldosterone-Producing Adenoma. J Hypertens (2018) 36(3):619–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Azizan EA, Lam BY, Newhouse SJ, Zhou J, Kuc RE, Clarke J, et al. Microarray, qPCR, and KCNJ5 Sequencing of Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas Reveal Differences in Genotype and Phenotype Between Zona Glomerulosa- and Zona Fasciculata-Like Tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2012) 97(5):E819–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mulatero P, Tauber P, Zennaro MC, Monticone S, Lang K, Beuschlein F, et al. KCNJ5 Mutations in European Families With Nonglucocorticoid Remediable Familial Hyperaldosteronism. Hypertension (2012) 59(2):235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Akerstrom T, Willenberg HS, Cupisti K, Ip J, Backman S, Moser A, et al. Novel Somatic Mutations and Distinct Molecular Signature in Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas. Endocr Relat Cancer (2015) 22(5):735–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guo Z, Nanba K, Udager A, McWhinney BC, Ungerer JPJ, Wolley M, et al. Biochemical, Histopathological, and Genetic Characterization of Posture-Responsive and Unresponsive APA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2020) 105(9):e3224–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Backman S, Akerstrom T, Maharjan R, Cupisti K, Willenberg HS, Hellman P, et al. RNA Sequencing Provides Novel Insights Into the Transcriptome of Aldosterone Producing Adenoma. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):6269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wu VC, Huang KH, Peng KY, Tsai YC, Wu CH, Wang SM, et al. Prevalence and Clinical Correlates of Somatic Mutation in Aldosterone Producing Adenoma-Taiwanese Population. Sci Rep (2015) 5:11396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Murakami M, Yoshimoto T, Minami I, Bouchi R, Tsuchiya K, Hashimoto K, et al. A Novel Somatic Deletion Mutation of ATP2B3 in Aldosterone-Producing Adenom. Endocr Pathol (2015) 26(4):328–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kitamoto T, Suematsu S, Yamazaki Y, Nakamura Y, Sasano H, Matsuzawa Y, et al. Clinical and Steroidogenic Characteristics of Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas With ATPase or CACNA1D Gene Mutation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2016) 101(2):494–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dutta RK, Welander J, Brauckhoff M, Walz M, Alesina P, Arnesen T, et al. Complementary Somatic Mutations of KCNJ5, ATP1A1, and ATP2B3 in Sporadic Aldosterone Producing Adrenal Adenomas. Endocr Relat Cancer (2014) 21(1):L1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tan GC, Negro G, Pinggera A, Tizen Laim NMS, Mohamed Rose I, Ceral J, et al. Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas: Histopathology-Genotype Correlation and Identification of a Novel CACNA1D Mutatio. Hypertension (2017) 70(1):129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rege J, Nanba K, Blinder AR, Plaska S, Udager AM, Vats P, et al. Identification of Somatic Mutations in CLCN2 in Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas. J Endocr Soc (2020) 4:bvaa123. 10.1210/jendso/bvaa123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kem DC, Weinberger MH, Higgins JR, Kramer NJ, Gomez-Sanchez C, Holland OB. Plasma Aldosterone Response to ACTH in Primary Aldosteronism and in Patients With Low Renin Hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1978) 46:552–60. 10.1210/jcem-46-4-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lefebvre H, Cartier D, Duparc C, Lihrmann I, Contesse V, Delarue C, et al. Characterization of Serotonin(4) Receptors in Adrenocortical Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas: In Vivo and In Vitro Studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2002) 87:1211–6. 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zwermann O, Suttmann Y, Bidlingmaier M, Beuschlein F, Reincke M. Screening for Membrane Hormone Receptor Expression in Primary Aldosteronism. Eur J Endocrinol (2009) 160:443–51. 10.1530/EJE-08-0711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Albiger NM, Sartorato P, Mariniello B, Iacobone M, Finco I, Fassina A, et al. A Case of Primary Aldosteronism in Pregnancy: Do LH and GNRH Receptors Have a Potential Role in Regulating Aldosterone Secretion? Eur J Endocrinol (2011) 164:405–12. 10.1530/EJE-10-0879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lopez AG, Duparc C, Naccache A, Castanet M, Lefebvre H, Louiset E. Role of Mast Cells in the Control of Aldosterone Secretion. Horm Metab Res (2020) 52:412–20. 10.1055/a-1119-1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sonoyama T, Sone M, Miyashita K, Tamura N, Yamahara K, Park K, et al. Significance of Adrenocorticotropin Stimulation Test in the Diagnosis of an Aldosterone-Producing Adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2011) 96:2771–8. 10.1210/jc.2011-0573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. El Ghorayeb N, Bourdeau I, Lacroix A. Role of ACTH and Other Hormones in the Regulation of Aldosterone Production in Primary Aldosteronism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2016) 7:72. 10.3389/fendo.2016.00072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. St-Jean M, Bourdeau I, Martin M, Lacroix A. Aldosterone is Aberrantly Regulated by Various Stimuli in a High Proportion of Patients With Primary Aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2021) 106:e45–60. 10.1210/clinem/dgaa703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nishimoto K, Nakagawa K, Li D, Kosaka T, Oya M, Mikami S, et al. Adrenocortical Zonation in Humans Under Normal and Pathological Conditions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2010) 95:2296–305. 10.1210/jc.2009-2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gomez-Sanchez CE, Qi X, Velarde-Miranda C, Plonczynski MW, Parker CR, Rainey W, et al. Development of Monoclonal Antibodies Against Human CYP11B1 and CYP11B2. Mol Cell Endocrinol (2014) 383:111–7. 10.1016/j.mce.2013.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Williams TA, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Rainey WE, Giordano TJ, Lam AK, Marker A, et al. International Histopathology Consensus for Unilateral Primary Aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2021) 106:42–54. 10.1210/clinem/dgaa484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nanba K, Yamazaki Y, Bick N, Onodera K, Tezuka Y, Omata K, et al. Prevalence of Somatic Mutations in Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas in Japanese Patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2020) 105:e4066–73. 10.1210/clinem/dgaa595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nanba K, Omata K, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Stratakis CA, Demidowich AP, Suzuki M, et al. Genetic Characteristics of Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas in Blacks. Hypertension (2019) 73:885–92. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nishimoto K, Tomlins SA, Kuick R, Cani AK, Giordano TJ, Hovelson DH, et al. Aldosterone-Stimulating Somatic Gene Mutations Are Common in Normal Adrenal Glands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2015) 112:E4591–9. 10.1073/pnas.1505529112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Omata K, Anand SK, Hovelson DH, Liu CJ, Yamazaki Y, Nakamura Y, et al. Aldosterone-Producing Cell Clusters Frequently Harbor Somatic Mutations and Accumulate With Age in Normal Adrenals. J Endocr Soc (2017) 1:787–99. 10.1210/js.2017-00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Omata K, Satoh F, Morimoto R, Ito S, Yamazaki Y, Nakamura Y, et al. Cellular and Genetic Causes of Idiopathic Hyperaldosteronism. Hypertension (2018) 72:874–80. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nanba AT, Nanba K, Byrd JB, Shields JJ, Giordano TJ, Miller BS, et al. Discordance Between Imaging and Immunohistochemistry in Unilateral Primary Aldosteronism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (2017) 87:665–72. 10.1111/cen.13442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fernandes-Rosa FL, Giscos-Douriez I, Amar L, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Meatchi T, Boulkroun S, et al. Different Somatic Mutations in Multinodular Adrenals With Aldosterone-Producing Adenoma. Hypertension (2015) 66:1014–22. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fernandes-Rosa FL, Williams TA, Riester A, Steichen O, Beuschlein F, Boulkroun S, et al. Genetic Spectrum and Clinical Correlates of Somatic Mutations in Aldosterone-Producing Adenoma. Hypertension (2014) 64:354–61. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nanba K, Chen AX, Omata K, Vinco M, Giordano TJ, Else T, et al. Molecular Heterogeneity in Aldosterone-Producing Adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2016) 101:999–1007. 10.1210/jc.2015-3239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dekkers T, ter Meer M, Lenders JW, Hermus AR, Schultze Kool L, Langenhuijsen JF, et al. Adrenal Nodularity and Somatic Mutations in Primary Aldosteronism: One Node is the Culprit? J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2014) 99:E1341–51. 10.1210/jc.2013-4255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. De Sousa K, Boulkroun S, Baron S, Nanba K, Wack M, Rainey WE, et al. Genetic, Cellular, and Molecular Heterogeneity in Adrenals With Aldosterone-Producing Adenoma. Hypertension (2020) 75:1034–44. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]