Abstract

Introduction and Aims.

This article examines the feasibility of leveraging Twitter to detect posts authored by people who use opioids (PWUO) or content related to opioid use disorder (OUD), and manually develop a multidimensional taxonomy of relevant tweets.

Design and Methods.

Twitter messages were collected between June and October 2017 (n = 23 827) and evaluated using an inductive coding approach. Content was then manually classified into two axes (n = 17 420): (i) user experience regarding accessing, using, or recovery from illicit opioids; and (ii) content categories (e.g. policies, medical information, jokes/sarcasm).

Results.

The most prevalent categories consisted of jokes or sarcastic comments pertaining to OUD, PWUOs or hypothetically using illicit opioids (63%), informational content about treatments for OUD, overdose prevention or accessing self-help groups (20%), and commentary about government opioid policy or news related to opioids (17%). Posts by PWUOs centered on identifying illicit sources for procuring opioids (i.e. online, drug dealers; 49%), symptoms and/or strategies to quell opioid withdrawal symptoms (21%), and combining illicit opioid use with other substances, such as cocaine or benzodiazepines (17%). State and public health experts infrequently posted content pertaining to OUD (1%).

Discussion and Conclusions.

Twitter offers a feasible approach to identify PWUO. Further research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of Twitter to disseminate evidence-based content and facilitate linkage to treatment and harm reduction services.

Keywords: opioid use disorder, social media, Twitter messaging

Introduction

Social media has augmented existing approaches to public health surveillance. Twitter’s application programming interface offers unprecedented access to user perceptions and experiences related to their health in real-time. Indeed, several studies have now reported on the feasibility of categorising Twitter content related to emerging tobacco products and psychostimulant misuse [1–3]. For instance, Thompson and colleagues reported improved perceptions of cannabis among adolescents on Twitter following the legalisation of recreational cannabis in California [4].

Twitter is also uniquely positioned to reduce the burden of chronic disease among hard-to-reach populations who commonly utilise Twitter (i.e. African-Americans, young adults) [5,6]. Online communities via Twitter facilitate longitudinal support among peers with chronic disease, reduce depression and stress symptoms related to these conditions, and ease access to evidence-based content and treatment [7]. However, few studies have monitored user-generated Twitter content related to opioid use disorder (OUD). Chary et al. [8] utilised natural language processing and user metadata to identify the geographic variation of Twitter content describing prescription opioid misuse in the US. Importantly, posts describing prescription opioid misuse were semantically distinct from unrelated tweets and correlated strongly with National Surveys on Drug Usage and Health state-by-state estimates of prescription opioid misuse [8]. Kalyanam et al. demonstrated the feasibility of isolating Twitter messages related to prescription opioid misuse risk behaviours and identifying illicit prescription opioid sales trafficked via Twitter using an unsupervised machine learning algorithm [9,10]. A limitation of these studies is the lack of information pertaining to perceptions and experiences with illicit opioids (e.g. heroin, fentanyl), poly-substance use and seeking treatment for OUD.

Identifying posts related to illicit opioid use are critical for timing interventions enhancing linkage to harm reduction (e.g. naloxone) and treatment during critical susceptible times, including opioid-related withdrawal symptoms, overdose and attempts to solicit peers in social media for help securing treatment for OUD. Towards elaborating on Twitter content related to illicit opioid use that could drive interventions facilitating access to harm reduction and treatment for people who use opioids (PWUO), this paper aimed to provide content analysis of user perceptions related to illicit opioids (e.g. heroin, fentanyl), including among PWUOs, and manually developing a multidimensional taxonomy of relevant tweets.

Methods

Tweets posted between June and October 2017 (n = 23 827) were collected using Twitter’s application programming interface over a three-month period from December 2017 to March 2018. After evaluating third-party platforms to capture relevant tweets, the study team ultimately utilised Twitter Scraper (http://bitlib.org/twitter/index.php). This publicly available platform collects tweets included on the public time-line per fixed time intervals. Search terms were based on prior studies conducted by the principal investigator pertaining to online health information and illicit opioid search patterns among PWUOs [11]. These search terms were then refined after a preliminary review of our Twitter sample, including heroin withdrawal (n = 14 479), heroin relapse (n = 3768), where can I get heroin (n = 1092), did heroin last night (n = 1331), where can I get smack (n = 1490), I am in recovery (n = 1149) and tried fentanyl (n = 518)] [11,12]. Tweets were then excluded if they were redundant, spam, marketing posts or not in English (n = 6407).

The coding team consisted of medical and public health students (SG, ST, CM), and an addiction medicine physician (BT) trained in qualitative research methods. Posts were manually classified into two axes: (i) experiences accessing, using or recovering from illicit opioids among Twitter users with OUD; and (ii) content categories pertaining to OUD posted by all Twitter authors (e.g. policies, medical information, jokes/sarcasm). Tweet authors were categorised as PWUO if they elicited any criteria for the diagnosis of OUD per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (i.e. withdrawal symptoms, cravings, opioid overdose, desire or unsuccessful efforts to reduce opioid use), requested treatment for OUD or were soliciting illicit opioids [12]. The coding team developed and refined the coding scheme in daily group meetings using an iterative method to develop, split or collapse categories within each of the two axes. A sample of 200 randomly assigned tweets was classified by the study team until interannotator agreement surpassed a kappa level of 0.7. The sample size of tweets and approach to achieving interannotater agreement are similar in scope to prior studies analysing tweets related to substance use disorders [2,4].

The study team then independently classified posts (n = 17 420) and discrepancies regarding coding were then discussed at least daily among annotators until consensus was reached. The senior author (BT) reviewed 30% of independently coded tweets to ensure adherence to the coding protocol.

Results

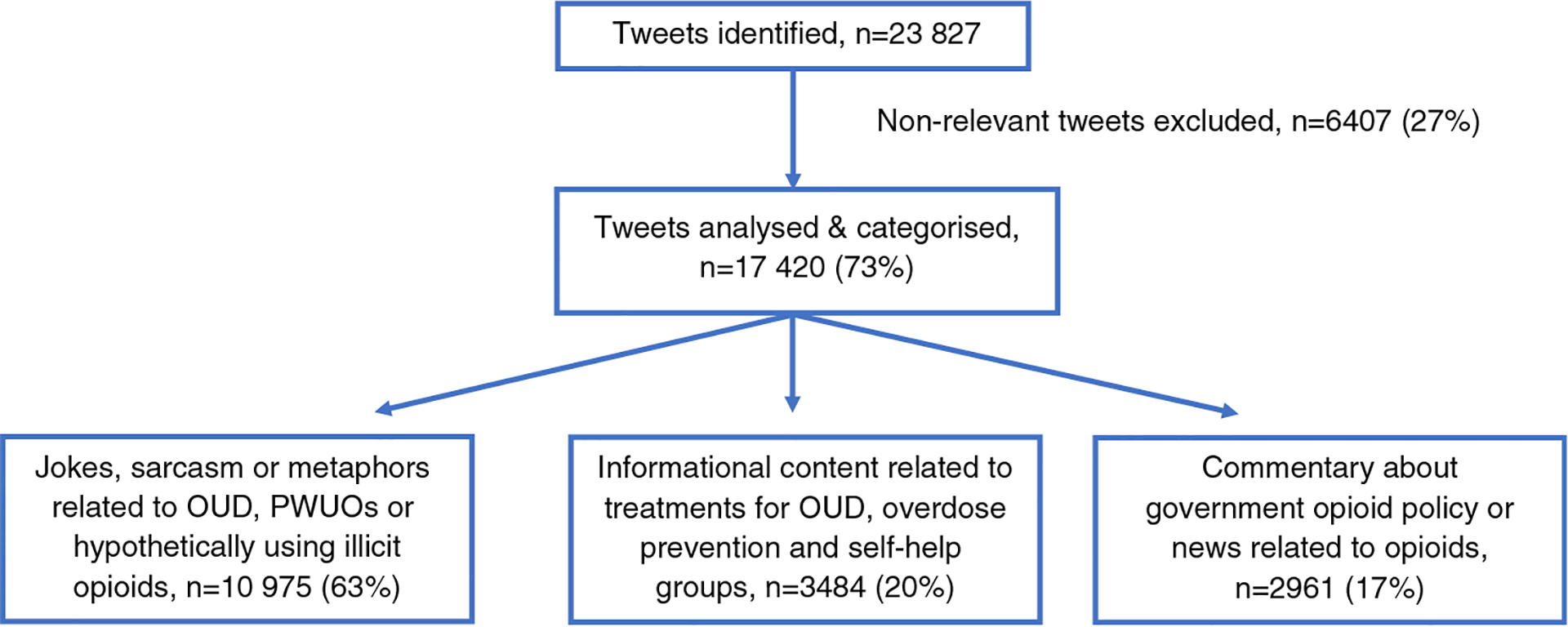

A total of 17 420 tweets were analysed and categories centered on: (i) jokes, sarcasm or metaphors related to OUD, PWUOs or hypothetically using illicit opioids (63%); (ii) informational content related to treatments for OUD, overdose prevention and self-help groups (20%); and (iii) commentary about government opioid policy or news related to opioids (17%; see Figure 1). A subset of informational content pertaining to overdose prevention, OUD treatment and policy were authored by state officials and public health experts (1%).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of search and exclusion of tweets, n (%). OUD, opioid use disorder; PWUO, people who use opioids.

Tweets posted by PWUOs (n = 1093) related to identifying illicit sources for procuring opioids (i.e. online, drug dealers; 49%), symptoms and/or strategies to quell opioid withdrawal symptoms (21%), and combining illicit opioid use with other substances (e.g. cocaine, benzodiazepines; 17%; see Table 1). Other posts by PWUOs divulged past or present personal experiences with illicit opioid use (6%), efforts to access treatment for OUD (2%, n = 25), surviving overdose events (0.5%), or about HIV prevention or treatment (0.1%). Posts by family or friends of PWUO recounted their experiences with an acquaintance diagnosed with OUD (2%) and often elicited peers for treatment resources and emotional support.

Table 1.

Experiences and themes related to opioid use disorder (OUD)

| Personal experiences among PWUO* (n = 1093) | % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Seeking to purchase illicit opioids | 49 (535) | ‘Heroin? Where can I get a prescription?’ |

| Opioid withdrawal symptoms | 21 (229) | ‘I only quit heroin yesterday and I’m already having withdrawal symptoms.#Lol’ |

| Poly-substance use | 17 (185) | ‘The northeast is where I can get stupid drunk and high and experiment with acid, meth, heroin, shrooms, PCP, cocaine’ |

| Past or present opioid use experiences | 6 (69) | ‘I should actually be dead now. Did five bags of heroin last night. Such an utter fuck up I can’t even succeed at killing myself |

| Experiences seeking treatment for OUD | 3 (31) | ‘Where can I go to get help? I live in Cleve, OH. It took A LOT 4me2 ask, not beg4 help. Willing 2do ANYTHING2 get off heroin. Ruinin my life!!’ |

| Themes (n = 17 420) | % (n) | |

| Jokes, sarcasm, or metaphors about OUD | 63 (10 974) | ‘Decided to quit my job and pursue a career in stand-up comedy full time. Ok! Now, where can I get heroin and a ride to an open mic?’ |

| Informational content | 20 (3414) | ‘Unlike other drugs, #Heroin withdrawal will NOT kill you. Every life is worth it. Narcan gives addicts a second chance.’ |

| Commentary about PWUO or OUD | 17 (2926) | ‘I cannot believe places are making heroin injection centers where idiots can get high legally while a nurse watches to make sure they don’t OD’ |

| Posts by public health experts | 1 (244) | ‘A “cold-turkey” heroin detox simply means a heroin addict stops using without any assistance.’ posted by the Frederick County, MD Health Department |

PWUO, people who use opioids.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate the feasibility of leveraging Twitter to identify PWUO and caregivers of PWUO posting content pertaining to OUD. Analysed tweets yielded key insights into how PWUO, family/friends of PWUO and other individuals utilise Twitter. First, PWUO divulge personal information or intentions related to illicit opioids. Second, Twitter facilitates peer-to-peer exchange of experiences and informational content pertaining to both illicit opioid use and treatment for OUD. Third, reliable information pertaining to OUD, prevention, treatment and policy posted by public health experts is limited compared to jokes/sarcasm, marketing posts or content promoting or normalising illicit opioid use [4,10]. Lastly, Twitter offers family and friends of PWUO a venue to disseminate experiences and resources to support treatment for OUD.

The content demonstrates distinct opportunities for public health interventions, including: (i) disseminating ‘just-in-time’ treatment and harm reduction services among Twitter users posting about adverse experiences or challenges obtaining treatment for OUD using a bot system; (ii) guiding public health officials, harm reduction and treatment programs to identify Twitter users by location to enhance access to available resources; (iii) confronting stigma among general Twitter users posting jokes or sarcastic comments about PWUO or public health measures addressing OUD, and educating PWUO about how to intervene on stigma; and (iv) empowering caregivers of PWUO to identify harm reduction, treatment and stigma education resources.

Limitations to this study include potential interrater variability, misinterpretation of posts and incorrect identification of post authors. Our corpus of tweets may lack generalisability due to our limited sample size and number of search terms used to identify relevant posts. Lastly, Twitter Scraper is unable to capture private content on Twitter.

This study highlights the considerable promise of social media as a feasible platform to identify user perceptions and experiences related to illicit opioid use. Twitter offers an easily accessible and scalable approach to expand access to evidence-based interventions for OUD. Future research should assess the efficacy of Twitter-based interventions encouraging PWUOs on Twitter to link with harm reduction and treatment services.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA042140-01A1) and Substance Abuse Research Education and Training program (R25DA022461-12).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Hanson CL, Burton SH, Giraud-Carrier C, Barnes MD, Hansen B. Tweaking and tweeting: exploring Twitter for nonmedical use of a psychostimulant drug (Adderall) among college students. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Myslín M, Zhu S-H, Chapman W, Conway M. Using Twitter to examine behavior and perceptions of emerging tobacco products. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Aphinyanaphongs Y, Ray B, Statnikov A, Krebs P. Text classification for automatic detection of alcohol use-related tweets: A feasibility study. Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 15th International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration (IEEE IRI 2014): IEEE, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thompson L, Rivara FP, Whitehill JM. Prevalence of marijuana-related traffic on Twitter, 2012–2013: a content analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2015;18:311–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pew Research Center. Social Media Use in 2018. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2018. Available at: https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/ (accessed June 2019). [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sinnenberg L, Buttenheim AM, Padrez K, Mancheno C, Ungar L, Merchant RM. Twitter as a tool for health research: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2017;107:e1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].De la Torre-Díez I, Díaz-Pernas FJ, Antón-Rodríguez M. A content analysis of chronic diseases social groups on Facebook and Twitter. Telemed J E Health 2012;18:404–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chary M, Genes N, Giraud-Carrier C, Hanson C, Nelson LS, Manini AF. Epidemiology from tweets: estimating misuse of prescription opioids in the USA from social media. J Med Toxicol 2017;13:278–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kalyanam J, Katsuki T, Lanckriet GR, Mackey TK. Exploring trends of nonmedical use of prescription drugs and polydrug abuse in the Twittersphere using unsupervised machine learning. Addict Behav 2017;65: 289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mackey TK, Kalyanam J, Katsuki T, Lanckriet G. Twitter-based detection of illegal online sale of prescription opioid. Am J Public Health 2017;107:1910–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tofighi B, Leonard N, Greco P, Hadavand A, Acosta MC, Lee JD. Technology use patterns among patients enrolled in inpatient detoxification treatment. J Addict Med 2019;13:279–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]