Key Points

Question

Can a multicomponent intervention integrating best practices in infectious diseases and palliative care reduce antimicrobial and burdensome intervention use for suspected urinary and lower respiratory tract infections among nursing home residents with advanced dementia?

Findings

In this pragmatic cluster randomized clinical trial among 426 nursing home residents with advanced dementia, there was a nonsignificant reduction in antimicrobial use in the intervention arm. Chest radiography use was significantly lower in the intervention arm, but other burdensome procedures were unchanged.

Meaning

An intervention to improve infection management did not significantly reduce antimicrobial use among nursing home residents with advanced dementia.

Abstract

Importance

Antimicrobials are extensively prescribed to nursing home residents with advanced dementia, often without evidence of infection or consideration of the goals of care.

Objective

To test the effectiveness of a multicomponent intervention to improve the management of suspected urinary tract infections (UTIs) and lower respiratory infections (LRIs) for nursing home residents with advanced dementia.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A cluster randomized clinical trial of 28 Boston-area nursing homes (14 per arm) and 426 residents with advanced dementia (intervention arm, 199 residents; control arm, 227 residents) was conducted from August 1, 2017, to April 30, 2020.

Interventions

The intervention content integrated best practices from infectious diseases and palliative care for management of suspected UTIs and LRIs in residents with advanced dementia. Components targeting nursing home practitioners (physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and nurses) included an in-person seminar, an online course, management algorithms (posters, pocket cards), communication tips (pocket cards), and feedback reports on prescribing of antimicrobials. The residents’ health care proxies received a booklet about infections in advanced dementia. Nursing homes in the control arm continued routine care.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was antimicrobial treatment courses for suspected UTIs or LRIs per person-year. Outcomes were measured for as many as 12 months. Secondary outcomes were antimicrobial courses for suspected UTIs and LRIs when minimal criteria for treatment were absent per person-year and burdensome procedures used to manage these episodes (bladder catherization, chest radiography, venous blood sampling, or hospital transfer) per person-year.

Results

The intervention arm had 199 residents (mean [SD] age, 87.7 [8.0] years; 163 [81.9%] women; 36 [18.1%] men), of which 163 (81.9%) were White and 27 (13.6%) were Black. The control arm had 227 residents (mean [SD] age, 85.3 [8.6] years; 190 [83.7%] women; 37 [16.3%] men), of which 200 (88.1%) were White and 22 (9.7%) were Black. There was a 33% (nonsignificant) reduction in antimicrobial treatment courses for suspected UTIs or LRIs per person-year in the intervention vs control arm (adjusted marginal rate difference, −0.27 [95% CI, −0.71 to 0.17]). This reduction was primarily attributable to reduced antimicrobial use for LRIs. The following secondary outcomes did not differ significantly between arms: antimicrobials initiated when minimal criteria were absent, bladder catheterizations, venous blood sampling, and hospital transfers. Chest radiography use was significantly lower in the intervention arm (adjusted marginal rate difference, −0.56 [95% CI, −1.10 to −0.03]). In-person or online training was completed by 88% of the targeted nursing home practitioners.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cluster randomized clinical trial found that despite high adherence to the training, a multicomponent intervention promoting goal-directed care for suspected UTIs and LRIs did not significantly reduce antimicrobial use among nursing home residents with advanced dementia.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03244917

This cluster randomized clinical trial in 28 nursing homes in the Boston area tested the effectiveness of a multicomponent intervention to improve management of suspected urinary tract and lower respiratory infections in residents with advanced dementia.

Introduction

Infections and suspected infections are common in residents with advanced dementia.1,2 For those who reside in nursing homes, infection management is often characterized by antimicrobial misuse,2,3,4 emergence of multidrug-resistant organisms,2,5,6,7,8 use of burdensome procedures,9,10 and failure to consider goals of care. These residents also may not benefit clinically from treatment with antimicrobials,2,9,10,11,12 which are often prescribed without clinical evidence of a bacterial infection.2,3,4,13 Comfort is the most common goal of care for residents with advanced dementia, and the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of infections may not align with that goal.14

Uptake of recently issued guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for antimicrobial stewardship in nursing homes has been inconsistent.15,16,17 Multicomponent nursing home interventions that have been tested in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and have been shown to reduce antimicrobial use18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 have not been adopted into practice. Despite the need to align antimicrobial use at the end-of-life with goals of care,27,28 efforts to improve infection management in nursing homes have not integrated infectious disease and palliative care principles nor have they focused on residents with advanced dementia.

The objective of the Trial to Reduce Antimicrobial Use in Nursing Home Residents With Alzheimer Disease and Other Dementias (TRAIN-AD) was to evaluate a multicomponent intervention to improve the management of suspected infections in nursing home residents with advanced dementia by merging best practices from infectious diseases and palliative care.29 This report presents the intervention’s effectiveness in reducing the primary outcome: antimicrobial treatment courses for suspected urinary tract infections (UTIs) or lower respiratory infections (LRIs). Secondary outcomes included (1) antimicrobial courses for suspected UTIs and LRIs when consensus-based minimal criteria to initiate treatment were absent,2,30,31 and (2) burdensome procedures used to evaluate these episodes.

Methods

The TRAIN-AD was conducted from August 7, 2017, and April 30, 2020. The study was reviewed and approved by Hebrew SeniorLife’s Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was waived because the TRAIN-AD was deemed to be of minimal risk per the Regulations for the Protection of Human Subjects (45 CFR §46). Printed flyers posted in facilities and mailed to proxies described how to opt-out of data collection. The study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. The full trial design is detailed elsewhere29 and the trial protocol is available in Supplement 1.

Facilities and Randomization

Administrators of eligible nursing homes (>60 beds and within 60 miles of Boston) were mailed information and telephoned to solicit participation in the trial (Figure 1). Facility involvement included a 3-month start-up period and a 24-month implementation and data collection phase. Facilities were recruited in staggered waves every 4 months. In each wave, a statistician (M.L.S.) used a computer-generated algorithm to randomly allocate nursing homes to the intervention or control arm. Using data from Long-Term Care Focus,32 covariate-constrained randomization33,34 was used to minimize between-arm imbalances of characteristics potentially associated with advanced dementia care: a facility’s profit status and the number of Black residents per facility (dichotomized at the median).1,2,35 The number of residents with severe cognitive impairment per facility (dichotomized at the median) was also included in the covariate-constrained randomization to ensure a balance of these residents between arms.36

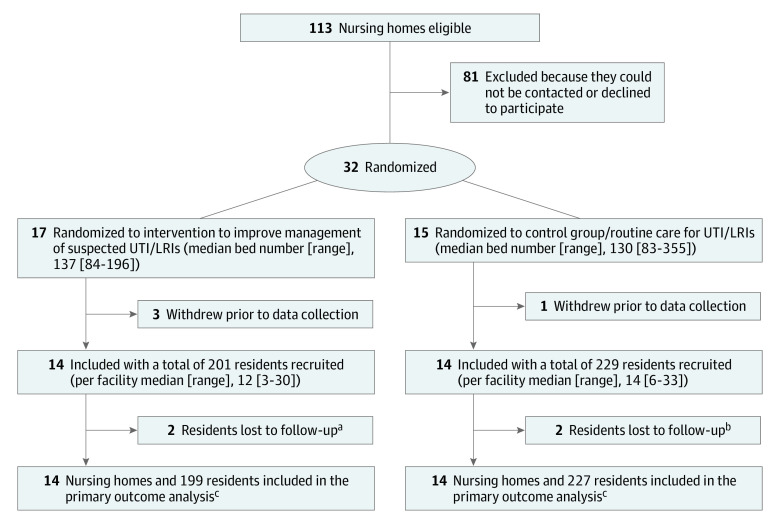

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram of Nursing Homes and Study Participants.

UTI denotes urinary tract infection; LRI, lower respiratory infection.

aFollow-up truncated by COVID-19 lockdown (n = 2).

bOpted out or withdrawn by health care proxy (n = 1) and discharged from nursing home after baseline assessment (n = 1).

cIncluded all residents with at least 1 follow-up assessment.

Participants

Resident enrollment in the trial was open from October 1, 2017, to February 24, 2020. Eligibility criteria included being 60 years of age or older and having dementia (any type), a Global Deterioration Scale37 score of 7 (range, 1-7; higher scores indicate worse dementia), a length of stay greater than 90 days, and an English-speaking health care proxy. During study initiation at each facility and every 2 months for as many as 12 months, research assistants asked nurses to identify eligible residents and confirmed eligibility by chart review.

At intervention facilities, the infection preventionist or director of nursing was designated as the site champion. During implementation start-up at each facility and every 6 months thereafter, the site champion generated a list of nursing home practitioners to target: (1) nurses working at least 2 shifts weekly, caring for advanced dementia residents; and (2) prescribing medical practitioners (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) caring for at least 2 residents with advanced dementia.

Intervention Structure and Implementation

During a 3-month facility start-up period, research and nursing home teams (eg, site champion, director of nursing, education specialists) cooperatively planned the intervention’s implementation. A protocol manual was provided.38 During implementation, the project director and site champion met monthly to problem-solve ongoing issues.

Intervention content integrated infectious diseases and palliative care best practices to improve management of suspected UTIs and LRIs in residents with advanced dementia. The infectious disease best practices centered on consensus-based minimal clinical criteria for empirical antimicrobial initiation in nursing homes that were adapted for residents with advanced dementia who cannot reliably communicate certain symptoms (eg, dysuria).2,30,31 Palliative care best practices focused on integrating residents’ preferences into treatment decisions and optimizing communication with their health care proxies.

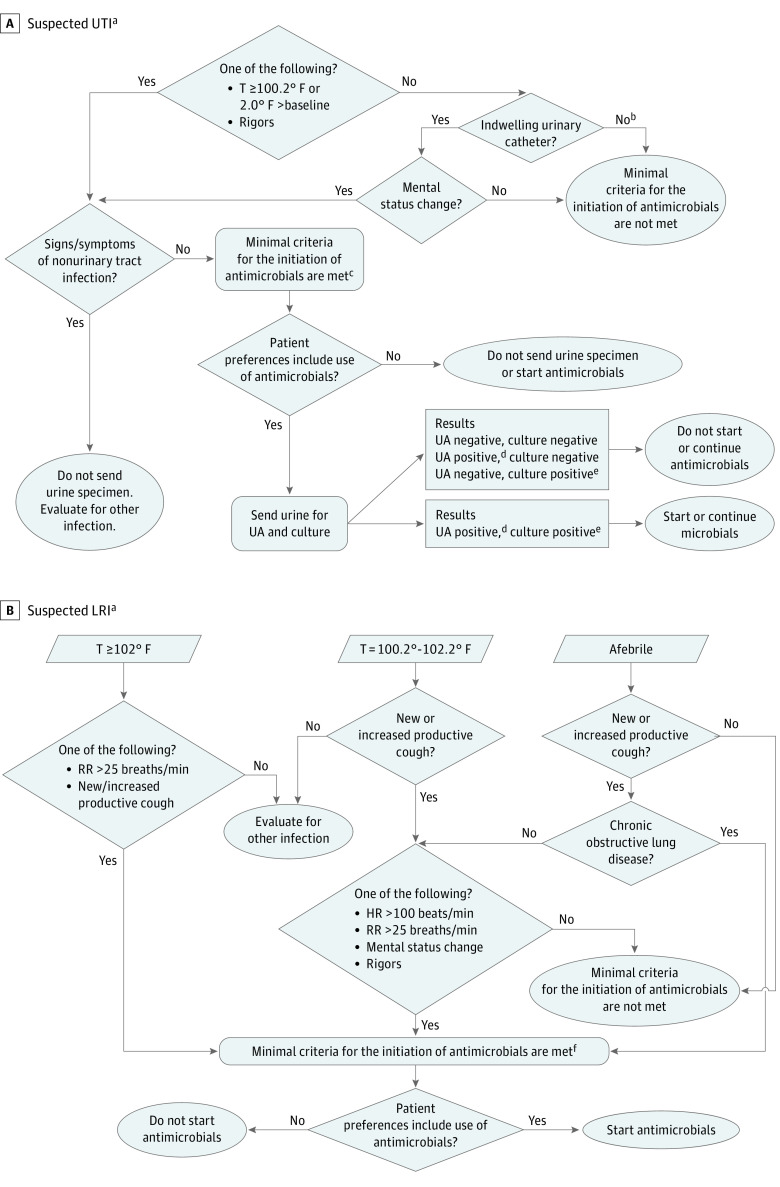

Intervention components for targeting nursing home practitioners included: an in-person seminar, an online course, management algorithms (posters and pocket cards; Figure 2), proxy communication tips (eMethods in Supplement 2), and feedback reports for prescribing antimicrobials. A booklet about infections in residents with advanced dementia was mailed to each resident’s proxy. The components were developed by experts in geriatrics, infectious diseases, and palliative medicine, guided by the literature,1,2,4,9,11,18,27,38,39,40 and were refined based on peer review and pilot-testing. Practitioners made final management decisions.

Figure 2. Management Algorithms for Suspected Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) and Lower Respiratory Infections (LRIs) in Nursing Home Residents With Advanced Dementia.

CFU denotes colony-forming units; HR, heart rate; RR, respiratory rate; T, temperature; and UA, urine analysis.

aAlgorithm applies to residents with dementia who are unable to meaningfully communicate information about symptoms typical of a UTI (eg, dysuria, suprapubic pain). The presence or absence of cloudy and/or odorous urine alone should not be used as an indication to send a urine specimen for evaluation or to start an antimicrobial.

bWithout an indwelling urinary catheter, mental status change alone is not an adequate symptom to support a diagnosis of a UTI.

cAntimicrobials may be initiated empirically while urine specimen results are pending.

dPositive urinalysis ≥10 000 white blood cells/L or dipstick results positive for white blood cells, leukocyte esterase, or nitrites.

ePositive urine culture: no indwelling urinary catheter ≥105 CFU/mL of ≥1 bacterial organism; with indwelling urinary catheter ≥ 103 CFU/mL.

fA complete blood cell count with differential and chest radiography may not be required for empiric antimicrobial treatment.

At implementation start-up, targeted practitioners were asked to attend a 1-hour in-person training seminar describing the program and infection management principles delivered by 1 of 3 physician-educators who were board-certified in both geriatric and palliative medicine.38 Providers unable to attend the 1-hour seminar were offered a 10-minute 1-on-1 mini-orientation by either the site champion or project director. Seminars were repeated every 6 months at each nursing home to train new practitioners, answer questions, and reinforce the training of established practitioners. The site champion was an on-site resource for practitioners throughout the implementation period.

Practitioners were also asked to complete a 45-minute online course, Infection Management in Advanced Dementia,41 composed of 4 cases of nursing home residents with advanced dementia (2 with UTIs and 2 with LRIs). Three videos integrated into the cases demonstrated communication strategies for challenging conversations with proxies.38 Learners completed a 10-item pretest and posttest knowledge assessment (score range, 0%-100%) and could repeat the posttest until they obtained the required score of 75%. Learners had 3 months to complete the course. The research team emailed reminders to noncompliant practitioners and gave their names to the site champions. Providers completing the course received a $50 gift card and 1 Continuing Medical Education (medical practitioners) or 1 Continuing Education Unit (nurses). Chromebooks were raffled off among participating practitioners in facilities achieving 67% completion.

Treatment management algorithms for suspected UTIs and LRIs (Figure 2) were printed on posters that were hung in nursing home units and on laminated pocket cards given to targeted practitioners; these algorithms were also integrated with the online course. The algorithms operationalized 2 main considerations for antimicrobial use: (1) alignment with residents’ preferences, and (2) presence of consensus-based minimal criteria for treatment initiation.2,30,31 Individualized feedback reports were emailed to prescribing practitioners every 2 months describing suspected UTI or LRI episodes for which they had prescribed antimicrobials when minimal criteria for treatment were absent. Practitioners received pocket cards with tips for communicating with proxies about infection management (eMethods in the Supplement 2).38

Residents’ proxies received a 6-page booklet by mail about infections in residents with advanced dementia, treatment options, and aligning treatment with goals of care. Practitioners were encouraged to review the booklets with proxies.

Control Arm

Facilities in the control arm continued routine care for suspected infections. No restrictions were placed in either arm with regard to other antimicrobial stewardship, advance care planning, or palliative care programs.

Data Collection and Elements

Data were abstracted from residents’ charts at baseline, every 2 months and for as many as 12 months, and within 30 days of death. Baseline data included: age, sex, race/ethnicity (Asian, Black, Hispanic, White, and unknown/not reported), comorbidities (ie, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus), hospice enrollment, and advance directives not to hospitalize and/or to withhold antimicrobials (ie, intravenous, intramuscular, or any route). Nurses rated each resident’s functional status by using the Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity Subscale (range, 7-28 points; higher scores indicate more disability).42 When applicable, date of death was ascertained from the resident’s chart.

At all follow-up assessments, 2 research assistants independently identified suspected UTIs and LRIs that occurred during the intervening period based on progress notes, tests (eg, urine cultures), and antimicrobial use. Inconsistencies were resolved by the nurse project director. Data abstracted for each episode included: signs (eg, temperature, respiratory rate), symptoms (eg, cough), and burdensome procedure use (ie, bladder catheterization, venous blood sampling, chest radiography, and hospital transfer). Suspected diagnosis and administration dates were collected for all antimicrobial courses. A 3-day treatment-free interval defined a separate antimicrobial course. More than 1 antimicrobial on a given day was considered a single course. Based on documented signs and symptoms, suspected UTIs and LRIs that were treated were categorized as meeting or not meeting consensus-based minimal criteria to initiate antimicrobials.2,30,31

Outcomes

The outcomes were measured for as many as 12 months. The primary outcome was the number of antimicrobial courses for suspected UTIs or LRIs per person-year. The secondary outcomes were (1) the number of antimicrobial courses for suspected UTIs or LRIs per person-year when minimal criteria for initiation were absent,2,30,31 and (2) the number of burdensome procedures (ie, bladder catheterization, venous blood draw, chest radiography, or hospital transfer) used to evaluate suspected UTIs or LRIs per person-years. Exploratory analyses examined antimicrobial courses prescribed for any indication per person-year.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed November 1, 2017, to January 22, 2021, using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), Stata, release 13.1 (StataCorp LLC), and R, version 3.4.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Frequencies described categorical variables and means with SDs or SEs described continuous variables. Analyses were conducted at the resident-level, followed intention-to-treat principles, and adjusted for clustering within nursing homes using robust estimates of variance.43 Adjusted analyses included covariates considered in the constrained randomization: facility profit status and resident’s race/ethnicity (Black or any other).

Negative binomial-logit hurdle regression models tested the intervention’s effect on all outcomes. This 2-part model included a logit model examining the probability of receiving at least 1 antimicrobial course, and a truncated negative binomial model examining the number of courses. Follow-up time was included as an offset. A 2-tailed test of the difference in adjusted marginal means examined the null hypothesis using a level of significance of P < .05. Bootstrapped SEs were obtained by resampling clusters,44 estimating the specified model for each bootstrap sample, and combining all estimates for the bootstrap samples.45 Adjusted marginal rate differences with 95% CIs were generated using the bootstrapped SEs.

Sample Size

Calculations were based on count regression adding a design effect to account for facility-level clustering,46,47 assumed 2-sided testing, type I error rate of 5%, and 90% power. Based on prior research,2 we assumed an intracluster correlation of 0.01, 15 residents per facility, an average of 0.79 person-years per resident, and 1.26 antimicrobial courses for suspected UTIs or LRIs per person-year in the control arm. We estimated that a sample size of 410 residents from 28 facilities (205 residents from 14 facilities per arm) was needed to achieve an absolute reduction of 0.38 (total reduction of 30%) for the primary outcome in the intervention vs control arm.

Masking

Research implementation team members could not be masked. The 2 research assistants who enrolled residents and collected their data, the principal investigator (S.L.M.), the statistician (M.L.S.), and the data programmers (D.A.H. and T.T.) were masked.

Results

Recruitment and Follow-up

At the 113 eligible nursing homes, 81 administrators could not be contacted or they declined participation (Figure 1), leaving 32 randomized facilities (intervention, n = 17; control, n = 15). Four facilities (intervention, n = 3; control, n = 1) dropped out prior to resident enrollment, leaving 28 participating facilities (14 per arm). Characteristics of the 14 facilities in each arm used in the constrained randomization in the intervention vs the control were:34 for profit, 7 (50%) and 6 (43%); the number of Black residents greater than the median, 7 (50%) and 7 (50%); and the number of residents with severe cognitive impairment greater than the median, 7 (50%) and 10 (71%).

There were 201 eligible residents in the intervention arm and 229 in the control (Figure 1). Two residents in the intervention arm and 1 in the control arm had a baseline assessment but no follow-up assessment and were excluded. One proxy opted out in the control arm. The final analytic sample included 199 residents in the intervention arm and 227 residents in the control arm. Because of the COVID-19 lockdown of Boston nursing homes, data collection ceased on March 10, 2020, slightly earlier than planned. At that time, 22 residents were still being followed and had completed these assessments: 10 months, n = 3; 8 months, n = 16; and 2 months, n = 3.

Resident Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, baseline demographic characteristics of residents in the intervention and control arms, respectively, were: mean age (SD), 87.7 (8.0) and 85.3 (8.6) years; 36 (18.1%) and 37 (16.3%) were men; 163 (81.9%) and 190 (83.7%) were women; 27 (13.6%) and 22 (9.7%) were Black; and 163 (81.9%) and 200 (88.1%) were White. Do-not-hospitalize orders were common but directives to withhold antimicrobial use were rare. Residents in both arms died: 82 (41.2%) in the intervention and 102 (44.9%) in the control arm.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Nursing Home Residents and 12-Month Follow-up.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 199) | Control (n = 227) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 87.7 (8.0) | 85.3 (8.6) |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 163 (81.9) | 190 (83.7) |

| Men | 36 (18.1) | 37 (16.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 163 (81.9) | 200 (88.1) |

| Black | 27 (13.6) | 22 (9.7) |

| Asian | 4 (2.0) | 2 (0.9) |

| Hispanic | 3 (1.5) | 0 |

| Unknown/not reported | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.3) |

| Alzheimer dementia (vs other dementia) | 89 (44.7) | 130 (57.3) |

| Comorbid conditions | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 26 (13.1) | 30 (13.2) |

| COPD | 17 (8.5) | 9 (4.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 47 (23.6) | 44 (19.4) |

| Hospice enrollment | 34 (17.1) | 34 (15.0) |

| Advance directives | ||

| No hospitalization | 103 (51.8) | 142 (62.6) |

| No intravenous antimicrobials | 3 (1.5) | 7 (3.1) |

| No intramuscular antimicrobials | 2 (1.0) | 4 (1.8) |

| No antimicrobials (any route) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) |

| Alzheimer severity subscale,a mean (SD) | 19.6 (2.3) | 20.4 (2.3) |

| Died during follow-up | 82 (41.2) | 102 (44.9) |

| Days of follow-up, median (IQR) | 360 (144-367) | 351 (116-362) |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity Subscale, range 7-28; higher scores indicate more functional disability.42

Practitioner Characteristics and Participation

There were 387 nursing home practitioners targeted in the intervention facilities (median [range], 27.5 [11-47] practitioners per facility) among whom 303 were nurses (78.3%) and 84 (21.7%) were prescribing practitioners (physicians, 38 [9.8%]; nurses, 44 [11.4%]; physician assistants, 2 [0.5%]). A total of 329 practitioners (85%) were on-boarded when implementation began in their nursing home, and 58 (15%), after implementation had started.

A total of 342 (88.4%) of practitioners completed either the online course or the training seminar, with 247 (63.8%) completing both activities. Among the 303 nurses, 288 (95%) completed either the online course or the training seminar, and 197 (65%) completed both activities. Among the 84 prescribing practitioners, 68 (81%) completed either the online course or the training seminar, and 52 (62%) completed both activities. For the online course, the mean (SD) pretest and posttest scores were 59% (21%) and 95% (7%), respectively.

Outcomes

During the 12-month study period, 27.1% and 33.9% of residents in the intervention and control facilities, respectively, received at least 1 antimicrobial treatment course for a suspected UTI or LRI (Table 2). For the primary outcome, antimicrobial courses for suspected UTIs or LRIs per person-year, the unadjusted rate (SE) of was 0.74 (0.12) in the intervention arm and 1.23 (0.34) in the control arm. The adjusted marginal rate of antimicrobial courses for suspected UTIs and LRIs per person-year was 33% lower in the intervention (0.55; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.84) vs the control arm (0.82; 95% CI, 0.49 to 1.14), but the difference was not significant (adjusted marginal rate difference, −0.27; 95% CI, −0.71 to 0.17; P = .23); the intraclass correlation for the primary outcome was 0.03. There was a nonsignificant reduction in the adjusted marginal rates of antimicrobial courses for suspected UTIs or LRIs when minimal criteria for treatment were absent per person-year in the intervention vs control arm (Table 2).

Table 2. Antimicrobial Treatment Courses Among Nursing Home Residents With Advanced Dementia During the 12-Month Study Period.

| Indication | Residents receiving ≥1 course, No. (%) | Adjusted marginal rate of antimicrobial courses per person-year (SE) [95% CI]a | Adjusted marginal rate difference (SE) [95% CI]b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 199) | Control (n = 227) | Intervention (n = 199) | Control (n = 227) | ||

| For suspected UTIs or LRIs | |||||

| Antimicrobial courses | 54 (27.1) | 77 (33.9) | 0.55 (0.15) [0.25 to 0.84] | 0.82 (0.17) [0.49 to 1.14] | −0.27 (0.22) [−0.71 to 0.17]c |

| Antimicrobial courses when minimal criteria for treatment absentd | 41 (20.6) | 50 (22.0) | 0.37 (0.11) [0.15 to 0.60] | 0.43 (0.10) [0.23 to 0.62] | −0.05 (0.15) [−0.35 to 0.24] |

| For suspected LRIs | |||||

| Antimicrobial courses | 36 (18.1) | 60 (26.4) | 0.32 (0.09) [0.13 to 0.50] | 0.55 (0.11) [0.33 to 0.77] | −0.24 (0.15) [−0.53 to 0.05] |

| Antimicrobial courses when minimal criteria for treatment absentd | 25 (12.6) | 33 (14.5) | 0.15 (0.05) [0.05 to 0.25] | 0.18 (0.04) [0.10 to 0.25] | −0.03 (0.06) [−0.15 to 0.10] |

| For suspected UTIs | |||||

| Antimicrobial courses | 25 (12.6) | 26 (11.5) | 0.20 (0.06) [0.08 to 0.32] | 0.19 (0.05) [0.09 to 0.29] | 0.01 (0.08) [−0.14 to 0.17] |

| Antimicrobial courses when minimal criteria for treatment absentd | 17 (8.4) | 19 (8.4) | 0.09 (0.03) [0.03 to 0.16] | 0.09 (0.02) [0.05 to 0.16] | 0.001 (0.04) [−0.08 to 0.08] |

| For any indication | |||||

| Antimicrobial courses | 70 (35.2) | 95 (41.9) | 0.82 (0.15) [0.52 to 1.13] | 1.19 (0.18) [0.83 to 1.56] | −0.37 (0.24) [−0.84 to 0.10] |

Abbreviations: LRI, lower respiratory infection; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Adjusted for facility profit status, resident race (Black vs other).

Marginal rate difference is expressed as intervention minus control.

Primary trial outcome, P = .23.

The reduction in antimicrobial courses in the intervention vs control arm was more marked for suspected LRIs (Table 2). Exploratory analysis revealed a nonsignificant reduction of 31% in the adjusted marginal rates of antimicrobial courses for any indication per person-year in the intervention vs control arm (adjusted marginal rate difference, −0.37; 95% CI, −0.84 to 0.10).

During the 12-month study period, 40.7% and 49.3% of residents in the intervention and control facilities, respectively, had at least 1 burdensome procedure for a suspected UTI or LRI (Table 3). The adjusted marginal rate of burdensome procedures per person-year was lower in the intervention vs control arm but not significantly. In stratified analyses, chest radiography use was significantly lower in the intervention vs control arm (adjusted marginal rate difference, −0.56; 95% CI, −1.10 to −0.03).

Table 3. Burdensome Procedures Used to Manage Suspected Urinary Tract or Lower Respiratory Infections Among Nursing Home Residents With Advanced Dementia During the 12-Month Study Period.

| Procedure | Residents experiencing ≥1 procedure, No. (%) | Adjusted marginal rate of procedures per person-year (SE) [95% CI]a | Adjusted marginal rate difference (SE) [95% CI]a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 199) | Control (n = 227) | Intervention (n = 199) | Control (n = 227) | ||

| Any procedureb | 81 (40.7) | 112 (49.3) | 1.07 (0.27) [0.54 to 1.60] | 1.69 (0.42) [0.87 to 2.51] | −0.62 (0.50) [−1.60 to 0.35] |

| Bladder catheterizationc | 49 (24.6) | 45 (19.8) | 0.47 (0.13) [0.21 to 0.73] | 0.37 (0.06) [0.25 to 0.49] | 0.11 (0.15) [−0.18 to 0.39] |

| Chest radiography | 53 (26.6) | 91 (40.1) | 0.53 (0.15) [0.24 to 0.83] | 1.10 (0.23) [0.65 to 1.55] | −0.56 (0.27) [−1.10 to −0.03] |

| Venous blood sampling | 60 (30.2) | 74 (32.6) | 0.64 (0.19) [0.28 to 1.00] | 0.76 (0.18) [0.41 to 1.11] | −0.12 (0.26) [−0.62 to 0.38] |

| Hospital transfer | 23 (11.6) | 20 (8.8) | 0.18 (0.07) [0.04 to 0.31] | 0.14 (0.03) [0.07 to 0.20] | 0.04 (0.08) [−0.11 to 0.19] |

Adjusted for facility profit status and residents’ race (Black vs other).

Any procedure includes bladder catheterization, venous blood sampling, chest radiography, and hospital transfer.

Bladder catheterization to obtain a urine specimen for urinalysis and/or urine culture.

Discussion

This cluster RCT found a 33% (statistically nonsignificant) reduction in antimicrobial courses for suspected UTIs and LRIs among residents with advanced dementia in nursing homes randomized to the TRAIN-AD intervention vs routine care. This reduction was primarily attributable to fewer antimicrobial courses for suspect LRIs, in keeping with a significant reduction in chest radiography use in the intervention arm. There was high practitioner adherence to the training components of the TRAIN-AD intervention.

Interpretation of these findings merits several considerations. While most outcomes trended in a direction reflecting less intensive care for suspected infections in the intervention arm, insufficient power may have accounted for the fact that these reductions, except for chest radiography use, were not statistically significant. Key assumptions in the power calculations were accurate, including the unadjusted rate of the primary outcome in the control arm (estimated, 1.26; actual, 1.23) and its reduction in the intervention arm (estimated, 30%; actual, 33%). However, a larger than anticipated intraclass correlation (estimated, 0.01; actual, 0.03) and varied number of residents within clusters, may have contributed to an underestimation of the sample size.

A one-third reduction in antimicrobials use would likely be considered meaningful by most clinicians caring for residents with advanced dementia. However, it is notable that the reduction was primarily for suspected LRIs. Suspected LRIs are common terminal events among residents with advanced dementia for whom comfort is the most common goal of care.1,3,9,48,49 More aggressive treatment of LRIs has been associated with greater discomfort and little clinical benefit in this population.9 Thus, a program integrating infectious disease and palliative principles that promotes less aggressive care for suspected LRIs has potential clinical relevance. Antimicrobial overuse for suspected UTIs in frail nursing home residents is well-recognized, and the focus of many policy and research efforts.18,22,50,51,52,53 Over time, these efforts may have motivated practice change such that there was less opportunity to “move the needle” in UTI management. Accordingly, antimicrobial use was lower for suspected UTIs than for LRIs in TRAIN-AD, whereas the opposite was observed in a similar cohort examined a decade ago.2

Implementing multicomponent interventions is challenging and low fidelity is a common culprit for inconclusive cluster RCTs in nursing homes.54 Regrettably, unlike several ongoing trials,24,52,55 rigorous evaluation of implementation fidelity was not incorporated into the TRAIN-AD design.56,57 Thus, while we achieved strong practitioners adherence to training activities, other moderators of implementation fidelity were not well captured, such as practitioners receptiveness to modifying their practice, practitioners utilization of the guidance materials over time, and the degree to which they enacted training principles when managing infections. Thus, it is possible that suboptimal intervention fidelity contributed to the nonsignificant findings. Ongoing analyses will examine whether specific training components, the “dose” of training (ie, completion of 1 or both training opportunities, mini vs full seminar), or practitioner type influenced the effectiveness of the intervention.

Limitations

Several limitations deserve comments. Findings may not be generalizable outside of Boston.35,58,59,60 Inadequate power and suboptimal implementation fidelity may have accounted for the nonsignificant findings. In addition, the intervention may have led to differential documentation of suspected infections between arms. However, antimicrobial use was reduced for all indications in the intervention vs the control arm (eg, not just UTIs or LRIs), thus this possibility was likely not an important source of bias.

Conclusions

The TRAIN-AD study demonstrated that training to promote a patient-centered and clinically sound approach to infection management in residents with advanced dementia can be delivered to nursing home practitioners. However, the effectiveness of the TRAIN-AD intervention to reduce antimicrobial use remains inconclusive. The TRAIN-AD highlighted critical design considerations for cluster RCTs of complex interventions,51,52,55 particularly conservative estimation of the intraclass correlation, and a priori inclusion of implementation fidelity evaluation grounded in comprehensive frameworks.56,57 Nonetheless, signals of effectiveness, high adherence to training, and the clinical importance of infection management in residents with advanced dementia merit consideration of a larger RCT testing an adapted TRAIN-AD intervention implemented in a nursing home health care system.

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Quick tips on communication pocket card

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1529-1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell SL, Shaffer ML, Loeb MB, et al. Infection management and multidrug-resistant organisms in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1660-1667. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Agata E, Mitchell SL. Patterns of antimicrobial use among nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):357-362. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Agata E, Loeb MB, Mitchell SL. Challenges in assessing nursing home residents with advanced dementia for suspected urinary tract infections. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(1):62-66. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loeb MB, Craven S, McGeer AJ, et al. Risk factors for resistance to antimicrobial agents among nursing home residents. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(1):40-47. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mody L, Bradley SF, Strausbaugh LJ, Muder RR. Prevalence of ceftriaxone- and ceftazidime-resistant gram-negative bacteria in long-term-care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22(4):193-194. doi: 10.1086/503397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Agata EM, Habtemariam D, Mitchell S. Multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria: inter- and intradissemination among nursing homes of residents with advanced dementia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(8):930-935. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pop-Vicas A, Mitchell SL, Kandel R, Schreiber R, D’Agata EM. Multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria in a long-term care facility: prevalence and risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1276-1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01787.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Givens JL, Jones RN, Shaffer ML, Kiely DK, Mitchell SL. Survival and comfort after treatment of pneumonia in advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(13):1102-1107. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yates E, Mitchell SL, Habtemariam D, Dufour AB, Givens JL. Interventions associated with the management of suspected infections in advanced dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(6):806-813. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dufour AB, Shaffer ML, D’Agata EMC, Habtemariam D, Mitchell SL. Survival after suspected urinary tract infection in individuals with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(12):2472-2477. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fried TR, Gillick MR, Lipsitz LA. Whether to transfer? factors associated with hospitalization and outcome of elderly long-term care patients with pneumonia. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(5):246-250. doi: 10.1007/BF02599879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mody L. Optimizing antimicrobial use in nursing homes: no longer optional. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(8):1301-1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01253.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell SL, Shaffer ML, Cohen S, Hanson LC, Habtemariam D, Volandes AE. An advance care planning video decision support tool for nursing home residents with advanced dementia: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):961-969. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Core elements of antibiotic stewardship for nursing homes. Accessed April 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/longtermcare/prevention/antibiotic-stewardship.html

- 16.Stone PW, Herzig CTA, Agarwal M, Pogorzelska-Maziarz M, Dick AW. Nursing home infection control program characteristics, CMS citations, and implementation of antibiotic stewardship policies: a national study. Inquiry. 2018;55:46958018778636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal M, Dick AW, Sorbero M, Mody L, Stone PW. Changes in US nursing home infection prevention and control programs from 2014 to 2018. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(1):97-103. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loeb M, Brazil K, Lohfeld L, et al. Optimizing antibiotics in residents of nursing homes: protocol of a randomized trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2002;2(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-2-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loeb M, Brazil K, Lohfeld L, et al. Effect of a multifaceted intervention on number of antimicrobial prescriptions for suspected urinary tract infections in residents of nursing homes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;331(7518):669. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38602.586343.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mody L, Krein SL, Saint S, et al. A targeted infection prevention intervention in nursing home residents with indwelling devices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):714-723. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monette J, Miller MA, Monette M, et al. Effect of an educational intervention on optimizing antibiotic prescribing in long-term care facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(8):1231-1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasay DK, Guirguis MS, Shkrobot RC, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship in rural nursing homes: impact of interprofessional education and clinical decision tool implementation on urinary tract infection treatment in a cluster randomized trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40(4):432-437. doi: 10.1017/ice.2019.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, et al. Effectiveness of an antimicrobial stewardship approach for urinary catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1120-1127. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Ward K, et al. A 2-year pragmatic trial of antibiotic stewardship in 27 community nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(1):46-54. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettersson E, Vernby A, Mölstad S, Lundborg CS. Can a multifaceted educational intervention targeting both nurses and physicians change the prescribing of antibiotics to nursing home residents? a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(11):2659-2666. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Bertrand R, et al. Successfully reducing antibiotic prescribing in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):907-912. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juthani-Mehta M, Malani PN, Mitchell SL. Antimicrobials at the end of life: an opportunity to improve palliative care and infection management. JAMA. 2015;314(19):2017-2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fairweather J, Cooper L, Sneddon J, Seaton RA. Antimicrobial use at the end of life: a scoping review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;bmjspcare-2020-002558. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loizeau AJ, D’Agata EMC, Shaffer ML, et al. The trial to reduce antimicrobial use in nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):594. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3675-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loeb M, Bentley DW, Bradley S, et al. Development of minimum criteria for the initiation of antibiotics in residents of long-term-care facilities: results of a consensus conference. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22(2):120-124. doi: 10.1086/501875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell SL, Shaffer ML, Kiely DK, Givens JL, D’Agata E. The study of pathogen resistance and antimicrobial use in dementia: study design and methodology. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56(1):16-22. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown University Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research . Long-term care (LTCfocus): facts on care in the US. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://ltcfocus.org/

- 33.Altman DG, Bland JM. Treatment allocation by minimisation. BMJ. 2005;330(7495):843. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7495.843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaffer ML, D’Agata EMC, Habtemariam D, Mitchell SL. Covariate-constrained randomization for cluster randomized trials in the long-term care setting: application to the TRAIN-AD trial. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2020;18:100558. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2020.100558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Roy J, Kabumoto G, Mor V. Clinical and organizational factors associated with feeding tube use among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2003;290(1):73-80. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V. The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Med Care. 2017;55(9):e68-e72. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(9):1136-1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Back A, Arnold R, Edwards K, Tulsky J. VITALtalk. Accessed October 20, 2020. https://www.vitaltalk.org/

- 39.Mehr DR, van der Steen JT, Kruse RL, Ooms ME, Rantz M, Ribbe MW. Lower respiratory infections in nursing home residents with dementia: a tale of two countries. Gerontologist. 2003;43(2):85-93. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Steen JT, Ooms ME, Adèr HJ, Ribbe MW, van der Wal G. Withholding antibiotic treatment in pneumonia patients with dementia: a quantitative observational study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(15):1753-1760. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harvard Medical School . Management of infections in advanced dementia. Accessed April 16, 2021. https://cmeregistration.hms.harvard.edu/events/management-of-infections-in-advanced-dementia/event-summary-53d7938c94b14613b8acb0e7f214e881.aspx?5S,M3,53d7938c-94b1-4613-b8ac-b0e7f214e881=&RefID=cmecatalog

- 42.Volicer L, Hurley AC, Lathi DC, Kowall NW. Measurement of severity in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol. 1994;49(5):M223-M226. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.M223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams RL. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):645-646. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00645.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cameron AC, Gelbach JB, Miller DL. Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. Rev Econ Stat. 2008;90(3):414-427. doi: 10.1162/rest.90.3.414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davison AC, Hinkle DV. Bootstrap Methods and Their Application. Cambridge University Press; 1997. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511802843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amatya A, Bhaumik D, Gibbons RD. Sample size determination for clustered count data. Stat Med. 2013;32(24):4162-4179. doi: 10.1002/sim.5819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rutterford C, Copas A, Eldridge S. Methods for sample size determination in cluster randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):1051-1067. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanson LC, Zimmerman S, Song MK, et al. Effect of the goals of care intervention for advanced dementia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):24-31. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen SM, Volandes AE, Shaffer ML, Hanson LC, Habtemariam D, Mitchell SL. Concordance between proxy level of care preference and advance directives among nursing home residents with advanced dementia: a cluster randomized clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(1):37-46.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . The core elements of antibiotic stewardship for nursing homes. Accessed September 21, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/longtermcare/prevention/antibiotic-stewardship.html

- 51.Ahouah M, Lombrail P, Gavazzi G, Chaaban T, Rothan-Tondeur M. ATOUM 6: does a multimodal intervention involving nurses reduce the use of antibiotics in French nursing homes?: a protocol for a cluster randomized study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(11):e14734. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rutten JJS, van Buul LW, Smalbrugge M, et al. Antibiotic prescribing and non-prescribing in nursing home residents with signs and symptoms ascribed to urinary tract infection (ANNA): study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):341. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01662-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in the elderly. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1997;11(3):647-662. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70378-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitchell SL, Volandes AE, Gutman R, et al. Advance care planning video intervention among long-stay nursing home residents: a pragmatic cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(8):1070-1078. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ford JH II, Vranas L, Coughlin D, et al. Effect of a standard vs enhanced implementation strategy to improve antibiotic prescribing in nursing homes: a trial protocol of the improving management of urinary tract infections in nursing institutions through facilitated implementation (IMUNIFI) study. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e199526. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hasson H. Systematic evaluation of implementation fidelity of complex interventions in health and social care. Implement Sci. 2010;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1212-1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1100347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Skinner J, et al. Churning: the association between health care transitions and feeding tube insertion for nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):359-362. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mitchell SL, Mor V, Gozalo PL, Servadio JL, Teno JM. Tube feeding in us nursing home residents with advanced dementia, 2000-2014. JAMA. 2016;316(7):769-770. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Quick tips on communication pocket card

Data Sharing Statement