Abstract

Background

Bispecific T cell engagers represent the majority of bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) entering the clinic to treat metastatic cancer. The ability to apply these agents safely and efficaciously in the clinic, particularly for solid tumors, has been challenging. Many preclinical studies have evaluated parameters related to the activity of T cell engaging BsAbs, but many questions remain.

Main body

This study investigates the impact of affinity of T cell engaging BsAbs with regards to potency, efficacy, and induction of immunomodulatory receptors/ligands using HER-2/CD3 BsAbs as a model system. We show that an IgG BsAb can be as efficacious as a smaller BsAb format both in vitro and in vivo. We uncover a dichotomous relationship between tumor-associated antigen (TAA) affinity and CD3 affinity requirements for cells that express high versus low levels of TAA. HER-2 affinity directly correlated with the CD3 engager lysis potency of HER-2/CD3 BsAbs when HER-2 receptor numbers are high (~200 K/cell), while the CD3 affinity did not impact potency until its binding affinity was extremely low (<600 nM). When HER-2 receptor numbers were lower (~20 K/cell), both HER-2 and CD3 affinity impacted potency. The high affinity anti-HER-2/low CD3 affinity BsAb also demonstrated lower cytokine induction levels in vivo and a dosing paradigm atypical of extremely high potency T cell engaging BsAbs reaching peak efficacy at doses >3 mg/kg. This data confirms that low CD3 affinity provides an opportunity for improved safety and dosing for T cell engaging BsAbs. T cell redirection also led to upregulation of Programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and 4-1BB, but not CTLA-4 on T cells, and to Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) upregulation on HER-2HI SKOV3 tumor cells, but not on HER-2LO OVCAR3 tumor cells. Using this information, we combined anti-PD-1 or anti-4-1BB monoclonal antibodies with the HER-2/CD3 BsAb in vivo and demonstrated significantly increased efficacy against HER-2HI SKOV3 tumors via both combinations.

Conclusions

Overall, these studies provide an informational dive into the optimization process of CD3 engaging BsAbs for solid tumors indicating that a reduced affinity for CD3 may enable a better therapeutic index with a greater selectivity for the target tumor and a reduced cytokine release syndrome. These studies also provide an additional argument for combining T cell checkpoint inhibition and co-stimulation to achieve optimal efficacy.

Keywords: antibody affinity, t-lymphocytes, immunotherapy

Cytotoxic T cells represent one of the main immunologic defenses against tumor progression. Cancer patients with high levels of T cell infiltrates generally demonstrate prolonged survival over those whose tumors lack T cells or human leukocyte antigen (HLA) expression.1 2 The prospect of using recombinantly derived monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) or bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) to engage cytotoxic T cells to target tumor cells expressing human or viral oncogenes, oncogenic mutations/translocations, or other overexpressed markers was introduced over three decades ago.3 4 Since then, two major strategies have emerged: (1) soluble BsAbs that bridge T cells and tumor cells and (2) recombinant expression of chimeric mAb/T cell coreceptor/coactivator proteins on cytotoxic T cells to direct recognition to a tumor antigen via the mAb.5 The approval of both a BsAb (blinatumomab/Blincyto) and multiple T cell-based therapies directed at the B cell antigen CD19 (Kymriah and Yescarta), and burgeoning clinical efficacy data for additional antigens found on immune cell subsets involved in lymphomas, leukemias, and myelomas, spurred approximately 300 clinical trials at the end of 2019.5 With clinical validation, the approach continues to grow at a furious pace across both academia and industry.5–7

However, technological hurdles prevented early success against solid tumors. These obstacles include an immunosuppressive milieu within the tumor microenvironment (TME), diminishing T cell activity, survival, and proliferation due to checkpoint inhibition and a lack of T cell costimulation8, and limited T cell extravasation into the solid tumor mass.9 Potential on-target/off-tumor targeting of normal tissues10 and potent cytokine release profiles raise safety concerns.11 12 Overcoming these hurdles has become a major area of research driving a new wave of T cell engagers, now transitioning from the preclinical into the clinical space.6

Although much remains to be done, recent progress has been made investigating molecular parameters related to the potency of T cell engaging BsAbs.13 For example, the relatively small size of the Bispecific T cell Engager (BiTE) format, using tandem Single-chain variable fragments (scFvs), contributes to their high potency redirecting T cells to kill tumor-associated antigen (TAA)-expressing cells. It is hypothesized that these small BsAbs enable the formation of tight junctions replicating the immune synapse observed during the recognition of antigen peptide-loaded HLA complexes by T cell receptors (TCRs) as well as the TCR/CD3 complex conformational changes during T cell activation.7 14 15 Some studies have directly compared varied BsAb formats versus BiTEs or versus each other.13 16 Membrane proximity of the TAA epitope is a key element for lysis potency and multiple studies demonstrated that close TAA epitope proximity to the membrane improves BsAb potency.17 18 Such epitope considerations may enable larger BsAb formats with other optimal properties such as improved pharmacokinetics, stability, and reduced immunogenicity.5 Previous studies have demonstrated the impact of affinity for either the TAA or CD3 on efficacy and safety, including the impact of CD3 affinity on both T cell activation and cytokine release.13 19–21

In this report, we investigate several of these critical parameters to provide insights into improved T cell engager BsAb designs. We first evaluate the in vitro and in vivo potency of two HER-2/CD3 BsAbs of varied format, and IgG, enabled by our previous technology work.22 23 We subsequently evaluate the affinity requirements directed against both the TAA and CD3 for in vitro and in vivo potency with a particular interest in cytokine release and immune receptor/ligand upregulation. Lastly, we investigate the in vivo potency of a BsAb optimized for both efficacy and safety in the presence and absence of a T cell checkpoint inhibitor or costimulatory molecule.

Methods

Bispecific molecular biology

The pertuzumab (anti-HER-2) sequence was obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The mouse SP34 anti-hCD3 mAb sequence has been published.16 24 The pertuzumab IgG1 mAb, SP34 IgG1_N297Q mAb, the IgG1AAQ BsAb, and tandem Fab heavy chains (HCs) were generated using overlapping PCR and plasmid constructs published previously.16 22 PCR products were cloned into a cytomegalovirus promoter-driven mammalian expression vector (Lonza) using the Clonables Kit (Novagen) and existing HindIII (5’) and EcoRI (3’) expression cassette restriction sites. The entire coding DNA sequence of the HER-2/CD3 tandem Fab HC, was generated using overlapping PCR with a (G4S)3 15 amino acid (aa) linker between the Fab HCs and cloned directly into the same mammalian vector. The pertuzumab and chimeric SP34 light chains (LCs) containing the Fab specificity mutations were synthesized similarly. All constructs utilized a murine kappa leader signal sequence. For generating HC and LC mutants, the QuikChange II Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent) was used per manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmid ligations, transformations, DNA preparations were performed using standard molecular biology protocols.

The mAbs and BsAbs were expressed in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells as described.25 Briefly, for the HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAbs, two HC plasmids and two LC plasmids were co-transfected at 2 µg DNA/mL culture using a 1:1:1:1 ratio. For the HER-2/CD3 tandem Fab, one HC plasmid and two LC plasmids were co-transfected at 3 µg DNA/mL culture using a 1:1:1 ratio. Transfected CHO cells were grown for 5 days at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) incubator while shaking at 125 rpm. Supernatants were harvested by centrifugation at 10 000 rpm for 5 min and filtered through 2 µm filters.

Purification, characterization, and pharmacokinetics evaluation are described in online supplemental methods.

jitc-2021-002444supp001.pdf (5.7MB, pdf)

BLI affinity studies of pertuzumab mutations

Bio-layer interferometry (BLI) experiments were performed on an Octet RED96 system (FortéBio). All steps of the assay were performed at 30°C with a plate shaking speed of 1000 rpm. Anti-human Fc biosensors were presoaked in Octet kinetic buffer (FortéBio, cat#18–1105) for 5 min prior to measurement. Next, biosensors were collected by the instrument and dipped into the first row of a black 96-well plate containing 200 µL solutions with 10 µg/mL pertuzumab variant (Loading) for 60 s. Biosensors were then moved to a new row containing Octet buffer to generate a baseline for subtraction. Next, biosensors were moved to solutions containing the soluble human HER-2 extracellular domain (Speed Biosystems, cat# YCP1045) for 300 s (Association Phase) followed by transfer to wells containing Octet kinetic buffer for 600 s (Dissociation Phase). The binding data was analyzed using Octet data analysis software and fit globally to a 1:1 binding reaction.

Flow cytometry

For all experiments, data were analyzed using FlowJo V.10, and, unless specified otherwise, acquisition was performed on a Becton Dickinson LSRFortessa flow cytometer using BD FACSDiva software.

Flow cytometric binding potency on SKOV3 and Jurkat tumor cells. Adherent SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells (ATCC Cat#HTB-77) cultured in RPMI 1640 /10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) Corning/gentamicin (Gibco) at 37°C, 5% CO2 were resuspended using Accutase (Innovative Technologies Cat#AT104). Jurkat cells (ATCC Cat#TIB-152) grew in suspension. Cells were centrifuged at 170 g for 7 min and washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). All subsequent steps were performed on ice. ‘Wash buffer’ contained PBS, 12% FBS, 0.05% Sodium Azide (NaN3) and 10% Normal Goat Serum. Cells were resuspended in Wash buffer and blocked for 15 min. Tumor cells (0.5×106 cells/well) were added to 96-well plates (Corning 3799). BsAbs and control mAbs were added to the wells starting at 100 nM for Jurkat cells and 67 nM for SKOV3 cells (except 100 nM for Tandem Fab), titrated using threefold dilutions, and incubated for 45 min. Cells were washed twice and supernatants were aspirated before adding secondary detection reagents in Wash buffer for 45 min. R-Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated Goat anti-Human kappa (Southern Biotechnology Cat#2060-09) was used for SKOV3 cells. Goat anti-Human lambda-PE (Southern Biotechnology Cat#2070–09) was used for Jurkat cells, except for the pertuzumab control where Goat anti-Human kappa-PE was used. Cells were washed twice again and resuspended in Wash buffer with PI (Molecular Probes Cat#P3566) before analysis.

Because affinity studies with monomeric CD3 has given us misleading information in the past, we have found more relevant to measure affinity by competition with Jurkat cells. Competition flow cytometry with SP34-PE mAb. Jurkat cells were resuspended in Blocking buffer (Wash buffer supplemented with Human BD Fc Block (BD Biosciences Cat#564 220)) for 15 min, pelleted, washed twice, and 50 µL of cells (0.5×106 cells/well in Wash buffer) added to 96-well plates (Corning 3799). Next, cells were centrifuged at 170 g for 7 min and Wash buffer was aspirated. In a separate 96-well plate (Corning 3879), the BsAb and control mAbs were added to wells starting at 1000 nM and titrated using threefold dilutions (working concentrations were 2×). BsAb and mAb dilutions were mixed with equal volume of SP34-PE (final concentration of 3 µg/mL, BD Biosciences Cat#552127). This sample mixture was added to the cells and incubated 45 min. Cells were washed three times before resuspension in Wash buffer with PI (Molecular Probes Cat#P3566) and then analyzed on a BD LSRII flow cytometer.

Flow cytometric evaluation of cell surface proteins on T cells 48 hours after mixing SKOV3 cells and biologic test articles is further described in online supplemental methods. Briefly, human T cells (ALLCELLS frozen normal human peripheral blood CD3+ Pan T cells, Cat# PB009-1F, Lot #A5715/Donor 1 and A5647/Donor 2) were removed from redirected lysis assay plates after co-cultured for 48 hours in RPMI 1640 /10% FBS Corning/gentamicin (Gibco) at 37°C, 5% CO2 with SKOV3 tumor cells, various IgGs and IgG BsAbs (E:T 10:1). Human T cells were stained with Alexa-488 Mouse Anti-Human CD4 (BD Biosciences Cat#557695) and Pacific Blue Mouse Anti-Human CD8 (BD Biosciences Cat#558207). Labeled T cell activation markers: APC-Cy7 Mouse Anti-Human CD69 (BD Biosciences Cat#557756) and APC-Mouse Anti-Human CD25 (BD Biosciences Cat#555434) were used with Donor 1 and incubated for 45 min. Labeled checkpoint inhibitors: PerCP-eFluor 710 Mouse Anti-Human CD279 (PD-1) (Invitrogen cat#46-2799-42), APC-Mouse Anti-Human CD152 (CTLA-4) (Biolegend Cat#349908) and PE-Mouse anti-Human CD137 (4-1BB) (BD Biosciences Cat#561701) were used with Donor 2. Finally, the cells were resuspended in Wash buffer with 1:1000 PI (Molecular Probes Cat#P3566) and analyzed along with OneComp eBeads (eBioscience Cat#01-1111-42).

Quantitation of HER-2 and PD-L1 receptors per cell by flow cytometry is further described in online supplemental methods. The SKOV3 (ATCC Cat#HTB-77) and OVCAR3 (ATCC Cat#HTB-161) adherent tumor cells (RPMI 1640 /10% FBS (Corning), gentamicin (Gibco), 37°C, 5% CO2) were stained for expression of PD-L1 and resuspended in LIVE/DEAD stain PI (Molecular Probes Cat#P3566) to assess cell viability. Quantibrite PE beads (BD Bioscience Cat# #340495) were used to determine the number of cell surface HER-2 receptors/tumor cell according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vivo studies with SKOV3-Luc in NSG-His mice

NSG-His mice engrafted with human T cells were generated in the Stem Cell and Xenograft Core at the University of Pennsylvania. Briefly, immunodeficient NSG mice between 7–9 weeks of age were injected intravenously with 30 mg/kg of busulfan to condition their bone marrow niche. Mice were injected intravenously with ≥100 k cord blood-derived CD34+ cells, 22–26 hours later. After 12 weeks, reconstitution levels were assessed and only mice having a sufficient level of T cells (≥5% huCD3+/huCD45+) were retained for in vivo studies.

Xenograft tumors were established by subcutaneous injection of 106 SKOV3 cells expressing Luciferase (SKOV3-Luc) into the flanks of the NSG-His mice. Mice received 50 mg of intravenous immunoglubulin (IVIG, Privigen, Behring) intraperitoneally, 24 hours before tumor cell inoculation. At indicated days, mice received intravenous or intraperitoneal injections of control IgGs or BsAbs. Tumors were measured two times per week with caliper, and volumes were calculated as V=1/2×length×width×height. Tumor implantation was verified by bioluminescence imaging before treatment with BsAbs or control antibodies. Bioluminescence imaging was performed with a Lumina IVIS imaging system and quantified with the Living Image software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 150 mg/kg D-luciferin (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, Massachusetts, USA) and imaged under isoflurane anesthesia at the peak of photon emission.

Mice were euthanized when tumor diameter was ≥2 cm or if they exhibited any sign of suffering that could not be relieved.

Statistical analyses

Statistics are calculated for each of the tumor models’ Max Radiance or Caliper data by transformation to a log scale to equalize variance across time and treatment groups. The log radiance data are analyzed with a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance, with a Spatial Power correlation structure, by time and treatment using the MIXED procedures in SAS software (V.9.3). Treated groups are compared with the control group at each time point. The MIXED procedure is also used separately for each treatment group to calculate least squared means and SEs at each time point. Both analyses account for the autocorrelation within each animal and the loss of data that occurs when animals with large tumors are removed from the study early.

Results

Comparison of HER-2/CD3 tandem Fab and IgG BsAbs

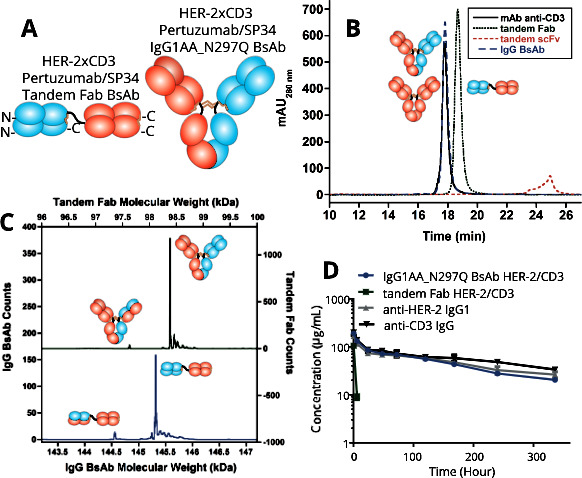

We first investigated potency and pharmacokinetic differences between different formats of HER-2/CD3 BsAbs. We chose pertuzumab (anti-HER-2) and SP34 (anti-CD3) as the parental mAbs for constructing the BsAbs.16 26 Three BsAb formats were generated including a tandem scFv (BiTE format), a tandem Fab, and a human IgG1 rendered effectorless by mutating Leu234 and Leu235 both to alanine and Asn297 to glutamine (backbone denoted hIgG1AAQ, figure 1A).27 The tandem scFv format did not express stably and only fragments were ever recovered (figure 1B). With the more stable Fab components,28 the tandem Fab and the IgG BsAb expressed well and assembled properly (figure 1B). As assessed using an HPLC method with an in-line electrospray mass spectrometer, both the tandem Fab and IgG BsAbs were >90% correctly assembled (figure 1C). Thus, while the BiTE format did not yield properly folded material, the stable tandem Fab and IgG BsAbs were suitable for further functional characterization.

Figure 1.

Biophysical characterization and murine pharmacokinetics of HER-2/CD3 BsAbs. (A) Schematic diagrams of the tandem Fab and IgG BsAbs. The linker between the Fabs within the tandem Fab BsAb comprises a (G4S)3 15 amino acid (aa) sequence. (B) Analytical size-exclusion chromatography of the HER-2/CD3 BsAbs including a tandem scFv (BiTE) BsAb that connected the VH/VL domains of each Fv using a 20 aa (G4S)3 linker and a 15 aa (G4S)3 linker between the Fvs. The tandem scFv was unstable and degraded when expressed multiple times. (C) Intact mass spectra of the HER-2/CD3 IgG (green/above) and tandem Fab (blue/below) BsAbs indicating >95% correct HC/LC assembly. (D) Pharmacokinetic properties of the HER-2/CD3 IgG1AA_N297Q and tandem Fab BsAbs compared with the parental pertuzumab human IgG1 and chimeric SP34 human IgG1AA_N297Q mAbs on intravenous dosing (four mice/group; error bars are shown). BiTE, Bispecific T cell Engager; BsAb, bispecific antibody; mAb, monocolonal antibody; scFv, single-chain variable fragment.

Next, the pharmacokinetics properties of the two HER-2/CD3 BsAbs were tested. Male Balb/c mice were intravenously administered with 10 mg/kg of the BsAbs or SP34 hIgG1_N297Q control mAb. Pertuzumab IgG1 data was published previously.22 Neither arm of the BsAbs have reactivity to the mouse antigens (data not shown). As expected, the presence of the IgG Fc prolonged the serological persistence of the HER-2/CD3 hIgG1AAQ BsAb. The half-life was roughly 8 days, similar to that of the control mAbs (figure 1D). The tandem Fab HER-2/CD3 BsAb lacking an IgG Fc was cleared rapidly. Six hours after administration, >90% of the tandem Fab BsAb had cleared from the serum (figure 1D).

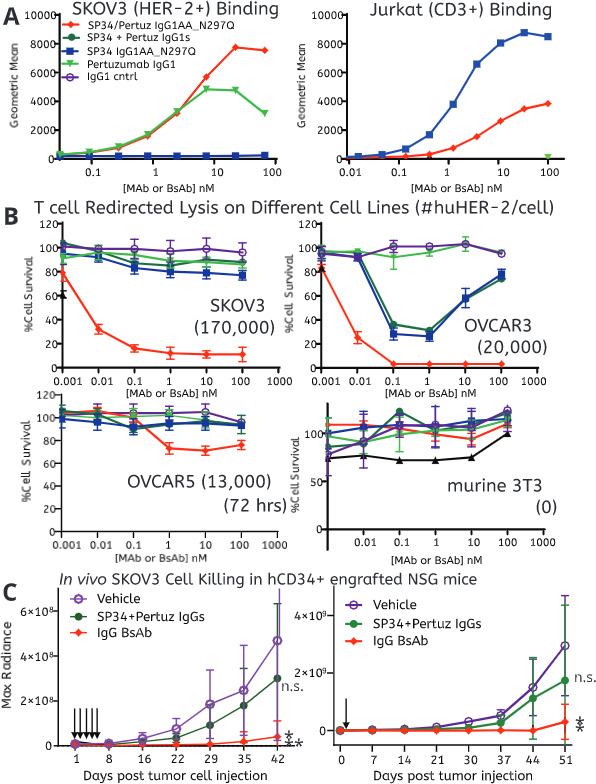

Tumor cell lines expressing varied levels of the HER-2 antigen were used to evaluate the ability of the HER-2/CD3 BsAbs to redirect primary human T cells to kill tumor cells. First, the BsAbs were assessed for their ability to bind both HER-2HI SKOV3 tumor cells and CD3+ Jurkat cells by flow cytometry (figure 2A and online supplemental figure 1A, B). Both BsAbs bound both cell types in a dose-dependent manner. As expected, pertuzumab only bound SKOV3 cells while SP34 only bound Jurkat cells (figure 2A and online supplemental figure 1A, B). Three tumor cell lines, SKOV3, OVCAR3, and OVCAR5, expressing high to low levels of human HER-2, respectively (quantified using BD Quantibrite Beads, online supplemental figure 2A, B) were subjected to human T cells (E:T 10 T cells/) and titrated amounts of either of the BsAbs or their parental mAbs. Adherent mouse 3T3 cells (human HER-2 negative) were used as a negative control. After 48 hours, both BsAbs potently (EC50 <10 pM) induced lysis of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 tumor cells (figure 2B). The difference in potency was much smaller than differences observed between the two formats with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)/CD3 BsAbs,16 indicating that BsAb format does not generally lead to substantial differences in potency. Interestingly, the primary T cells displayed an allogeneic response to OVCAR3 when stimulated by SP34 without TAA-mediated redirection (figure 2B). It is unclear why, but a possibility is that with the donors used, there may be more allogeneic reactivity with this cells line. SP34 demonstrated the typical bell-shaped activation curve known for CD3 agonist mAbs.29 30 The IgG BsAb had little activity towards HER-2LO OVCAR5 cells and no activity towards the HER-2neg 3T3 cell line (figure 2B). After 48 hours, the SP34 control mAb led to weak activation of the T cells with an slight increased of CD69 expression (but not CD25) regardless of the expression of HER-2 antigen, while the BsAbs strongly activated T cells only in the presence of HER-2HI cells with strong upregulation of both CD69 and CD25 (online supplemental figure 3).

Figure 2.

In vitro binding and in vitro and in vivo redirected T cell killing of HER-2HI, HER-2LO, and HER-2NEG cell lines. (A) Binding of the HER-2/CD3 BsAbs to HER-2HI SKOV3 (right) and CD3+ Jurkat (left) cells using flow cytometry. (B) Naïve T cell redirected killing of four different cell lines by the HER-2/CD3 BsAbs (10:1 E:T ratio). Each point is the average of three individual measurements and error bars are SD. The number in parentheses indicates the experimentally determined number of HER-2 receptors per cell. (C) In vivo T cell redirected killing of SKOV3 cells by the HER-2/CD3 BsAbs. The arrows indicate the dosing paradigm, either five daily doses (left panel, doses=black arrows) or a single dose (right panel, single dose=black arrow) starting 1 day after tumor cell implantation (**p<0.001; *p<0.05). Mice were treated with 5 mg/kg of antibodies. SKOV3-Luc tumor monitoring was performed longitudinally using bioluminescence imaging. BsAb, bispecific antibody; mAb, monoclonal antibody.

The two BsAbs were next evaluated for their in vivo T cell redirected lysis activity against SKOV3-Luc tumor cells implanted in human CD34+ stem cell engrafted NSG mice (NGS-His) with evidence of developed populations of circulating human T cells. A transduced firefly luciferase gene in SKOV3-Luc cells enables their tracking using bioluminescent imaging. Given the short half-life of the tandem Fab BsAb, we first compared the BsAbs using daily dosing starting 1 day after tumor cell inoculation. Under daily dosing conditions, both BsAbs significantly inhibited tumor growth (figure 2C). Tumor outgrowth was observed for all control mice (13/13) and all mice treated with the combination of pertuzumab hIgG1 and SP34_IgG1_N297Q (5/5) (figure 2C). Based on caliper measurements, the IgG BsAbs eliminated tumor cells with late tumor outgrowth in only a single mouse each group (1/5) (online supplemental figure 4A).

Next, the BsAbs’ ability to eliminate tumor outgrowth was evaluated following a single injection on day 1. Sera were collected at different time points after BsAb administration. The IgG BsAb persisted in serum as observed in Balb/c mice (online supplemental table 1 and figure 1D). BsAbs eliminated the initial outgrowth of tumor, suggesting that the majority of T cell redirected lysis activity occurs early in the murine model (figure 2C). Eventual tumor outgrowth was evaluated by caliper measurement. After 50 days only two out of five mice treated with the IgG BsAb demonstrated outgrowth, suggesting a benefit to the persistence of the IgG BsAb (online supplemental figure 4B). Elimination was dependent on the expression on the target cells as the IgG BsAb had no effect on the outgrowth of the HER-2LO OVCAR5 tumor (online supplemental figure 5).

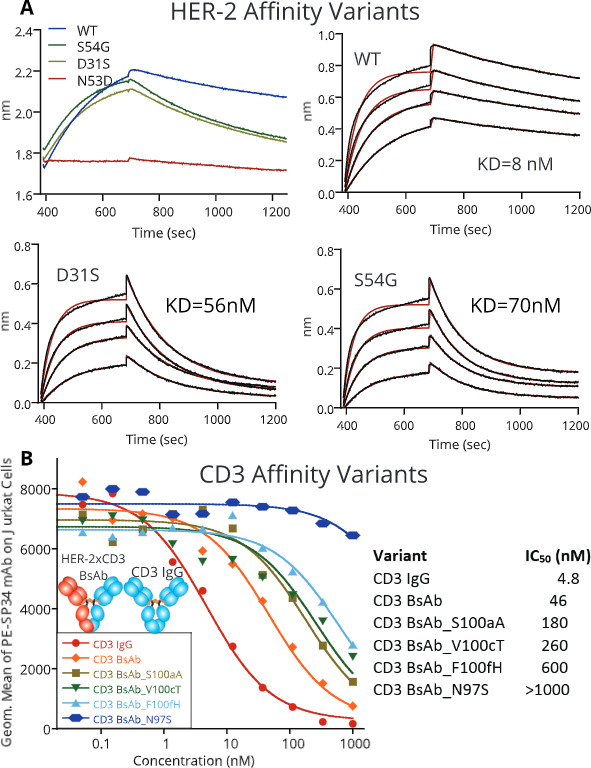

Evaluating varied affinity towards both HER-2 and CD3 for the IgG BsAb

Next, the IgG BsAb’s affinity to HER-2, CD3, or both arms was attenuated to determine the impact on T cell redirection. By evaluating the structure of pertuzumab bound to HER-2,31 a small library of approximately 20 point mutations was designed to lower pertuzumab’s affinity. The mutations were generated in the pertuzumab IgG format, expressed at small scale in CHO cells and tested for their affinity towards soluble, monomeric HER-2 using Bio-layer interferometry (B-LI). Three individual point mutations reduced the affinity of pertuzumab to HER-2 across two orders of magnitude. D31S and S54G reduced the affinity from 8 nM (wild-type) to 56 and 70 nM, respectively (Kabat numbering, figure 3A),32 while N53D reduced affinity ~100-fold with very poor binding detected by B-LI. These three mutations were chosen for further study.

Figure 3.

Affinity attenuation of the HER-2 and CD3 arms of HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAb. (A) Biosensor kinetics demonstrating an approximately sevenfold and ninefold affinity reduction of the pertuzumab arm binding to soluble human HER-2 antigen. The exact attenuating mutations are listed in the top left corner. (B) The impact of CD3 attenuating mutations within the IgG BsAb was measured using competition FACS displacement of a wild-type SP34 monoclonal antibody labeled with phycoerythrin. BsAb, bispecific antibody.

SP34 affinity variants were chosen rationally by making single mutations in heavy chain complementarity determining region 3 (HCDR3) since antibody HCDR3 residues are typically at the center of the epitope.33 We evaluated the relative affinities of SP34 variants in the IgG BsAb format by competition flow cytometry with wild-type, labeled SP34 on Jurkat cells (figure 3B). Four mutations reducing CD3 affinity, N97S (>21-fold), S100aA (fourfold), V100cT (sixfold), and F100fH (13-fold) were chosen for further study.

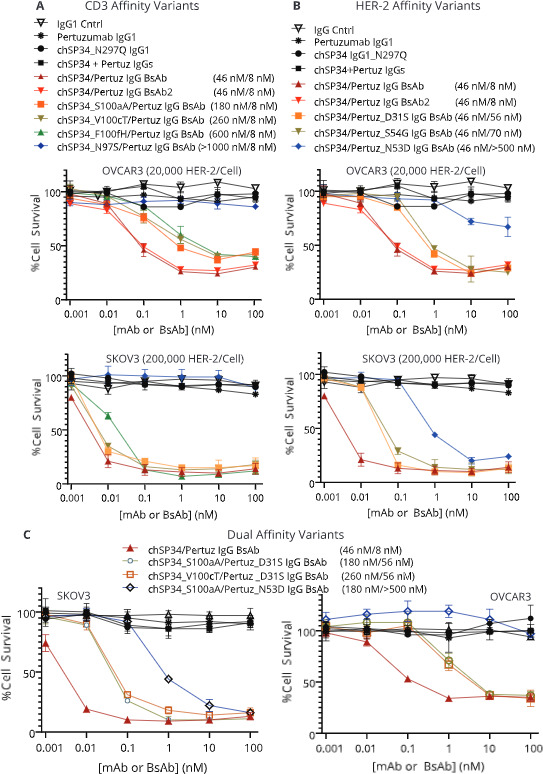

T cell redirection potency of affinity-attenuated IgG BsAbs was evaluated on both SKOV3 cells, expressing approximately 2×105 HER-2 receptors per cell, and OVCAR3 cells expressing approximately 2×104 HER-2 receptors per cell, in vitro. The two cells lines demonstrated an initial difference in susceptibility to redirected cells lysis that was about 100-fold, much more importance that their difference in level of HER-2 expression. On SKOV3 cells, reducing CD3 affinity by as much as 13-fold (IC50 ~600 nM), had little impact on T cell lysis potency at the 10:1 E:T ratio, suggesting that HER-2 engagement enabled significant avidity towards CD3 on T cells. On HER-2LO OVCAR3 cells, decreasing CD3 affinity led to reduced potency (figure 4A). As expected, reducing HER-2 affinity, led to decreases in BsAb potency on both tumor cell lines (figure 4B) likely due to an intrinsically fast off-rate for the wild-type SP34 arm.16 The redirected lysis potency of the dual HER-2 and CD3 affinity-attenuated IgG BsAbs were nearly indistinguishable from the IgG BsAbs with only HER-2 affinity attenuation when tested on SKOV3 HER-2HI cells (figure 4). On HER-2LO OVCAR3 cells; however, the affinity attenuation of both HER-2 and CD3 combined to reduce the potency of the IgG BsAbs (figure 4C). Thus, while the potency of the IgG BsAb is driven primarily by HER-2 potency on HER-2HI tumor cells, reducing CD3 affinity can reduce the potency of these BsAbs towards HER-2LO cells (as expected on normal cells), potentially improving their overall safety profile.

Figure 4.

(A) Impact of attenuating HER-2/CD3 BsAb affinity to CD3 (upper left panels), (B) HER-2 (upper right panels), or (C) both CD3 and HER-2 (bottom panels) on in vitro T cell redirected lysis activity towards OVCAR3 and SKOV3 tumor cells. On the upper panels, chSP34/Pertuz IgG BsAb and chSP34/Pertuz IgG BsAb2 are duplicates. BsAb, bispecific antibody; mAb, monoclonal antibody.

Next, a subset of affinity-attenuated IgG BsAbs was evaluated for their ability to kill HER-2HI SKOV3-Luc tumor cells in vivo. BsAbs with attenuated affinity for HER-2, CD3, or both were compared with the wild-type, high-affinity IgG BsAb. Because of the limited number of NSG-His mice that can be engrafted with the CD34+ cells obtained from one cord blood, not all constructs could be tested in vivo. As observed previously, the wild-type IgG BsAb significantly reduced SKOV3-Luc cell growth in vivo (figure 5A). Strong attenuation of HER-2 binding affinity (~100-fold) eliminated BsAb activity in vivo (figure 5A), while it only impacted the potency in vitro (figure 4B). There are many possible reasons for this, including differences in E:T ratios, inadequate tissue diffusion of the BsAbs, or poor tumor mass penetration by T cells, needs for higher doses in vivo or different dose frequency. Moderate HER-2 affinity attenuation (~10-fold) led to a significant reduction in tumor growth versus the vehicle for all imaging measurements after day 13 except for day 39 (p=0.093) and on all caliper measurements past day 13 (figure 5A). The high affinity HER-2 (8 nM)/low affinity CD3 (600 nM) IgG BsAb significantly reduced tumor growth versus vehicle for all measurements past day 6 except for day 39 (p=0.082) based on imaging and on all measurements past day 13 based on caliper measurements (figure 5A). The extremely low CD3 affinity for this BsAb, even with high HER-2 affinity, likely impacted the BsAb’s potency. Overall, however, the in vivo efficacy did correlate with the attenuated-affinity BsAb results in vitro.

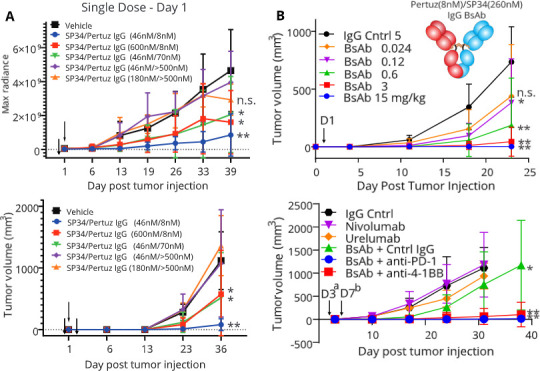

Figure 5.

In vivo studies with affinity-attenuated HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAbs. (A.) In vivo redirected lysis activity of affinity-attenuated HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAbs (one dose, 5 mg/kg). Tumor growth was measured using the bioluminescence of the SKOV3-Luc cell line (top panel) or physically using caliper measurements (bottom panel). IgG BsAb treatment was performed only once, 1 day after tumor cell inoculation (black arrow). (B). SKOV3 In vivo dose response study (top panel) and anti-PD-1 antagonist or anti-4-1BB agonist combination study (bottom panel) with the CD3 affinity-attenuated HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAb (SP34_V100cT, IC50=280 nM). For the PD-1/4-1BB combination study, the HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAb was injected intraperitoneally on Day 3a (0.6 mg/kg) after tumor cell inoculation to reduce its observed efficacy. The PD-1 antagonist mAb and 4-1BB agonist mAb were injected on Day 7b (10 mg/kg) after tumor cell inoculation to allow a period for receptor upregulation on T cells. BsAb, bispecific antibody; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PD-1, Programmed cell death 1 aka CD279.

Interferon (IFN)γ levels were measured in the sera of mice for those groups whose BsAbs achieved significant reductions in tumor growth. IFNγ levels were high in many (but not all) mice in the high affinity HER-2/high affinity CD3 BsAb group 2 days after dosing, but returned to baseline by the end of study (online supplemental table 2). The high affinity HER-2/low affinity CD3 BsAb group showed low IFNγ in serum at both time points (online supplemental table 2). Interestingly, the low affinity HER-2/high affinity CD3 BsAb group had low IFNγ 2 days after dosing, but still high IFNγ in multiple mice at the end of study (online supplemental table 2). However, given the potential for high cytokine release with both IgG BsAbs with high affinity to CD3, we decided to focus on a low CD3 affinity BsAb for further studies.

A dosing study was initiated to determine the relationship between efficacy and dose for a CD3 affinity-attenuated IgG BsAb in the HER-2HI SKOV3-Luc in vivo model. We used an IgG BsAb with high affinity to HER-2 (8 nM) and low affinity to CD3: the SP34_VH_V100cT mutation (280 nM IC50), because the SP34_VH_F100fH mutation (600 nM IC50) did not fully inhibit tumor growth at the relatively high dose of 5 mg/kg (figure 5A). Overall, the study demonstrated strong antitumor activity for this low CD3 affinity CD3 BsAb with significant decreases in tumor growth observed at doses as low as 0.12 mg/kg and just missing significance at 0.024 mg/kg (p=0.052) (figure 5B). Interestingly, maximal efficacy was observed at the highest dose of 15 mg/kg, but with near maximal efficacy observed for both 3 mg/kg and 0.6 mg/kg. No bell-shaped efficacy curve was observed as previously described for high affinity CD3 mAbs or BsAbs.19 34

Molecular immunology of HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAb T cell engagers

Molecular immunology aspects of the HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAbs functions were assessed from multiple angles in vitro. First, we tested for upregulation of various immune markers during redirected lysis assays with HER-2HI SKOV3 cells. Control mAbs, the HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAbs with wild-type affinity and 13-fold reduced affinity (SP34_VH_F100fH) to CD3 were assessed for their activation potential across the critical concentration range (0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 nM). T cells from these cultures were collected at 48 hours and tested for the upregulation of activation markers CD69 and CD25, immune checkpoint inhibitors PD-1 and membrane CTLA-4, and the costimulatory protein 4-1BB. No upregulation of any of the five markers was apparent in cultures containing either the IgG1 control or pertuzumab IgG (table 1, online supplemental figures 6 and 7). SP34 led to upregulation of CD69, fractional upregulation of CD25 and 4-1BB, and no upregulation of PD-1 or CTLA-4 (table 1 and online supplemental figure 7). Both the high and low CD3 affinity BsAbs induced strong upregulation of CD69, CD25, PD-1, and 4-1BB that diminished as the concentration was lowered (table 1, online supplemental figures 5 and 6). Only the high affinity HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAb upregulated CTLA-4 on a small fraction of T cells (table 1, online supplemental figure 7).

Table 1.

Primary CD8+ T cell activation markers and checkpoint inhibitors 48 hours after exposure to SKOV3 tumor cells and various IgGs and IgG BsAbs (10:1 E:T). Results were similar for CD4+ T cell activation markers and checkpoint inhibitors

| Test article | CD69 (%+) | CD25 (%+) | PD-1 (%+) | 4-1BB (%+) | CTLA-4 (%+) |

| IgG1 control 0.1 nM | 2.7 | 0 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 |

| IgG1 control 0.01 nM | 2.3 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0 |

| IgG1 control 0.001 nM | 2.1 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 |

| SP34 IgG1_N297Q 0.1 nM | 32.7 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 0 |

| SP34 IgG1_N297Q 0.01 nM | 5.8 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0 |

| SP34 IgG1_N297Q 0.001 nM | 1.8 | 0 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Pertuzumab IgG1 0.1 nM | 1.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pertuzumab IgG1 0.01 nM | 2.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pertuzumab IgG1 0.001 nM | 2.5 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 |

| SP34+Pertuz IgGs 0.1 nM | 26.1 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 3.7 | 0 |

| SP34+Pertuz IgGs 0.01 nM | 4.3 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| SP34+Pertuz IgGs 0.001 nM | 1.7 | 0.1 | 1 | 0 | 0.1 |

| SP34/Pertuz IgG BsAb 0.1 nM | 96.7 | 85.7 | 75.7 | 85.3 | 9.5 |

| SP34/Pertuz IgG BsAb 0.01 nM | 84.7 | 65.5 | 51.7 | 79.7 | 3.5 |

| SP34/Pertuz IgG BsAb 0.001 nM | 44.4 | 16.1 | 11.2 | 19.7 | 0.4 |

| SP34_F100fH/Pertuz IgG BsAb 0.1 nM | 87.5 | 73.8 | 56 | 80.9 | 2.3 |

| SP34_F100fH/Pertuz IgG BsAb 0.01 nM | 46.6 | 18.1 | 10.4 | 15.7 | 0.2 |

| SP34_F100fH/Pertuz IgG BsAb 0.001 nM | 3 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

BsAb, bispecific antibody; PD-1, Programmed cell death 1.

Next, both HER-2HI SKOV3 and HER-2LO OVCAR3 tumor cells were investigated for upregulation of PD-L1 during T cell redirected lysis assays using 1 nM levels of both high CD3 affinity (45 nM IC50) and low CD3 affinity (F100fH, 600 nM IC50) BsAbs. Both cell lines expressed PD-L1 endogenously at a low level; therefore, BD Quantibrite beads and flow cytometry were used to quantify PD-L1 receptor numbers. Both cell lines express PD-L1 endogenously at 2000–4000 receptors per cell (table 2 and online supplemental figure 8). After a 24-hour incubation with T cells and the IgG BsAbs (both high and low affinity to CD3), PD-L1 was upregulated approximately eightfold on SKOV3 cells, but only marginally on OVCAR3 cells (table 2 and online supplemental figure 8) even though redirected lysis was observed on both cell lines.

Table 2.

PD-L1 molecule numbers on SKOV3 or OVCAR3 cells 24 hours after exposure to primary T cells (10:1 E:T) and various IgGs and IgG BsAbs (0.1 nM). Columns with ‘fresh’ tumor cells were incubated for 24 hours with supernatants from the original redirected lysis assays cultures (T cells and original tumor cells removed by centrifugation), thus evaluating whether factors released into the supernatants of an active redirected lysis assay could induce PD-L1 upregulation on untreated tumor cells

| Test article | PD-L1 molecules per cell surface (SKOV3 cells+T cells) | PD-L1 molecules per cell surface (fresh SKOV3 cells+24-hour supernatant) | PD-L1 molecules per cell surface (OVCAR3 cells+T cells) | PD-L1 molecules per cell surface (fresh OVCAR3 cells+24-hour supernatant) |

| IgG1 Cntrl | 3500 | 7100 | 4500 | 1600 |

| SP34 IgG1_N297Q | 7700 | 5700 | 2000 | 1800 |

| Pertuzumab IgG1 | 3900 | 3000 | 2000 | 1600 |

| SP34+Pertuz IgGs | 8300 | 6200 | 2200 | 1800 |

| SP34/Pertuz IgG BsAb | 29 300 | 29 400 | 5900 | 3000 |

| SP34_F100fH/Pertuz BsAb | 24 300 | 27 300 | 5000 | 2900 |

BsAb, bispecific antibody; PD-L1, Programmed cell death-ligand 1; scFV, Single chain variable fragment.

T cell activation by major histocompatibility complex (MHC)/antigen recognition is known to induce their release of cytokines, such as IFNγ, that can upregulate PD-L1 on tumor cells35; therefore, cytokine release into the SKOV3/T cell culture supernatants when treated with controls or the HER-2/CD3 BsAbs (both high and low affinity) was assessed in vitro. Upregulation of multiple cytokines, most predominately IFNγ, was observed in the cell culture supernatants (online supplemental figure 9). Cytokine release correlated with the level of tumor cell killing observed for the high and low affinity BsAbs (figure 4 and online supplemental figure 9). Supernatants from the redirected lysis cultures were collected by centrifugation and applied to fresh SKOV3 or OVCAR3 cells. The culture supernatants induced PD-L1 upregulation on SKOV3 cells, and to a lesser extent on OVCAR3 cells, similar to that observed in the redirected lysis assays with T cells (table 2 and online supplemental figure 7) suggesting that soluble factors in the media, likely IFNγ, are inducing PD-L1 upregulation.

Given the upregulation of both PD-1 and 4-1BB on T cells and PD-L1 on SKOV3 cells observed in vitro with the HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAbs, an in vivo study was performed to investigate the impact of combining the HER-2/CD3 (SP34_V100cT, IC50=280 nM) IgG BsAb with either in-house produced nivolumab (anti-PD-1 antagonist) or urelumab (anti-4-1BB agonist), which were confirmed to bind the soluble PD-1 and 4-1BB, respectively (online supplemental figure 10). IgG BsAb treatment began 3 days after tumor inoculation, where the IgG BsAb showed reduced efficacy, allowing a window to observe improved efficacy when combining with other immunotherapies. Anti-PD-1 or anti-4-1BB were administered on day 7. In this study, neither anti-PD-1 nor anti-4-1BB alone induced antitumor activity, possibly because the allogeneic T cells response was insufficient to recognize SKOV3 tumor cells (figure 5B). IgG BsAb alone demonstrated weak, but significant efficacy (figure 5B). BsAb combination with nivolumab or urelumab led to significant and near-complete tumor eradication. The majority of mice treated with BsAb/anti-PD-1 (six of seven mice) or BsAb/anti-4-1BB (six of eight mice) showed no sign of tumor outgrowth at day 38, the end of the study (figure 5B). Overall, combination of T cell checkpoint inhibition or costimulation with a T cell engaging BsAb led to significantly improved efficacy over the individual modes of treatment.

Conclusions

Here we evaluated the impacts of BsAb’s arms respective affinities to T cell redirected lysis activity. In contrast with a previous study comparing an IgG BsAb with tandem Fab and tandem Fv (BiTE) BsAbs,16 the HER-2/CD3 IgG BsAb provided similar lysis potency as the tandem Fab BsAb in vitro, but with a clear in vivo pharmacokinetic advantage for the IgG BsAb. Discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo results can easily be explained by different E:T ratio. Although treatment occurred early after tumor implantation, the in vivo treatment of NSG-His mice seems closer to clinical conditions. Our results also showed that attenuating HER-2 affinity directly correlated with HER-2/CD3 BsAb potency for HER-2HI tumor, while CD3 potency was uncorrelated until CD3 affinity dropped to extremely low levels (~600 nM IC50). This TAA affinity correlation agrees with a recently published study also using HER-2/CD3 BsAbs as a model, which used trastuzumab instead of pertuzumab for HER-2 recognition.20 Trastuzumab has a much higher affinity than pertuzumab, which led to markedly reduced tolerability in cynomolgus monkeys, while nanomolar anti-HER-2 (similar to pertuzumab) was better tolerated.20 In our study, attenuation of CD3 affinity did not impact redirected lysis significantly and led to a reduced release of certain cytokines. An interesting new finding was that BsAb potencies on HER-2LO cells were impacted by lowering the affinity of either the anti-HER-2 or the anti-CD3 arm, suggesting that avidity is much poorer at antigen levels near 20K receptors per cell. Thus, a dichotomous affinity/efficacy relationship exists for BsAbs CD3 engagers that is intimately tied to the TAA expression levels.

Low affinity anti-CD3 may be a key feature of BsAb T cell engagers applied to solid tumors. Other than reduced cytokine release and improved dosing paradigms, a recent study demonstrated that lowering CD3 affinity improves BsAb biodistribution.21 Improved tumor-specific targeting was observed for low affinity against CD3 while high affinity led to BsAb accumulation in the spleen and lymph organs, unwanted T cell activation and BsAb catabolism.21 TAA versus CD3 affinity findings were related, but not entirely correlated using BsAbs on mobile tumor cells (eg, myelomas). Zuch de Zafra and colleagues showed that both CD38 and CD3 affinities impacted BsAb potency.36 Through a complex set of in vitro and in vivo experiments, the authors tuned the affinities to moderate (high single digit nM) to CD38 and low (~170 nM) to CD3 to enable tolerability along with efficacy,36 although the Phase 1 clinical trial was recently discontinued. Interestingly, we observed that a relatively higher dosing paradigm in vivo for the low affinity CD3 BsAb than is typical for standard BiTE molecules and a lack of a bell-shaped dose versus efficacy curve.37 A similar report by Trinklein and colleagues recently described a lack of efficacy at high doses for a high affinity anti-CD3 BsAb T cell engager versus a BsAb with low affinity to CD3 that targets a possibly less agonistic CD3 epitope.19 Overall, low affinity anti-CD3 with T cell redirecting BsAbs has shown benefits across many studies, including this one, limiting systemic cytokine release and improving biodistribution.

Numerous next generation protein engineering strategies are being tested to improve the tolerability of CD3 engagers. A future development could be the use of 2-to-1 BsAbs with two TAA-binding arms and one CD3 binding arm. These 2-to-1 BsAbs with lower TAA affinity provide a kinetic binding advantage to cells expressing high levels of TAA in close proximity to one another versus normal cells. Groups at Roche have spearheaded this concept with 2-to-1 molecules directed to CEA, CD20, and HER-2.38–40 Targeting TAA isoforms such as EGFRvIII or p85HER-2, expressed typically only on tumor tissues, is another strategy to limit normal cell toxicity.41 Lastly, activation of molecules in the TME via tumor associated-proteases has recently been described for a T cell engager.42 Overall, making C engagers more tolerable is an area of significant importance for their clinical utility.

While safety limitations have long plagued T cell redirecting BsAbs, efficacy in solid tumors has also been an issue. While lack of clinical success has been linked to on-target toxicity, cytokine release, or incomplete antigen expression or antigen escape, preclinical efficacy of T cell redirecting BsAbs is also limited by lack of prolonged T cell activation, T cell exhaustion and T cell apoptosis. There is growing evidence for these BsAbs being directly involved in upregulating the immune checkpoint receptors and ligands. As we show in this manuscript, preclinical evidence demonstrates that combining checkpoint inhibition with T cell redirectors can improve efficacy. For these reasons, many T cell engaging BsAbs and CAR T cells, provided they clear the safety hurdle, are being combined with checkpoint inhibitors in the clinic.10

Costimulation enabling prolonged T cell activity and survival has long been the territory of CAR T.43 Our study demonstrates how combining costimulation with T cell engaging BsAbs can significantly improve antitumor efficacy, allowing both reduced BsAb concentration but also delayed initial treatment, compared with the early treatment we used for BsAb only. Increased antitumor efficacy has also been demonstrated recently using a PSMA/CD3 IgG BsAb.44 MAbs inducing T cell costimulation, such as anti-4-1BB and anti-CD28, have been poorly tolerated due to systemic expression and activation of the targets; however, recent engineering approaches have yielded a new generation of costimulatory mAbs with attenuated activity to hopefully rebalance the risks/benefit profile of T cell costimulation.45 46 A prescient study in 1994 demonstrated powerful antitumor efficacy for the combination of a tumor specific costimulating BsAb (TAA/CD28) and a T cell redirecting BsAb (TAA/CD3).8 With the advent of new and robust methods for generating less immunogenic BsAbs,47 multiple groups have revived this strategy to provide T cell costimulation only within the tumor microenvironment.48 49 A recent molecule described by Wu and coworkers has taken the idea even further, combining both redirection and costimulation (like a CAR T) into a single off-the-shelf trispecific antibody targeting CD38(TAA)/CD3/CD28,50 with the anti-CD3/anti-CD28 arms in rigid alignment to favor cis-costimulation and avoid potential trans-mediated T cell fratricide.

In conclusion, this report provides a deep dive into many parameters of redirected lysis including BsAb affinity directed to both the TAA and CD3, as well as biology around checkpoint/costimulator upregulation during T cell redirection and the utility of intervening in these pathways to improve antitumor efficacy while minimizing systemic cytokine release for patient safety. This is an active and growing field and the data provided in this report adds to other efforts to define various parameters of T cell redirection with multispecific antibodies and should help in the design of next generation molecules with improved parameters for clinical success.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Benjamin Gutierrez for help with transient transfections, Michael Bacica for initial LCMS characterization, Carina Torres for flow cytometry discussions, and Heather Austin for Balb/c mice dosing and plasma collection. Additionally, we thank the Penn Stem Cell and Xenograft Core for providing NSG-His mice and the Small Animal Imaging Facility for animal imaging studies.

Footnotes

MP and AS contributed equally.

Correction notice: This paper has been updated since first published to update corresponding author details.

Contributors: MP and AS contributed equally to this publication. MP: Conceptualization, in vivo experimentation, writing—original draft, reviewing and editing, revisions. AS: Conceptualization, cell-based assays, flow cytometry, writing—original draft. XW: Conceptualization, biochemical/biophysical binding assays. FH: Purification and characterization of protein characteristics. JM and SC: Statistical evaluation of in vivo data. CC and AG: Conceptualization of in vitro and in vivo experiments and investigation methodology, original draft reviewing and editing. DJP and SD: Conceptualization, resources, supervision, writing—original draft, writing review, and editing.

Funding: This work was supported in part by the Lilly Research Laboratories and the Lilly Research Award Program (LRAP).

Competing interests: AS, XW, FH, JM, SC, CC, AG, and SD are or were employees of Eli Lilly.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Raw data for each of the figures are available upon request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

All studies were conducted under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee–approved protocols and within an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC)-accredited facility.

References

- 1.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, et al. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol 2002;3:991–8. 10.1038/ni1102-991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, et al. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:298–306. 10.1038/nrc3245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kranz DM, Tonegawa S, Eisen HN. Attachment of an anti-receptor antibody to non-target cells renders them susceptible to lysis by a clone of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1984;81:7922–6. 10.1073/pnas.81.24.7922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shalaby MR, Shepard HM, Presta L, et al. Development of humanized bispecific antibodies reactive with cytotoxic lymphocytes and tumor cells overexpressing the HER2 protooncogene. J Exp Med 1992;175:217–25. 10.1084/jem.175.1.217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strohl WR, Naso M. Bispecific T-cell redirection versus chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells as approaches to kill cancer cells. Antibodies 2019;8. 10.3390/antib8030041. [Epub ahead of print: 03 Jul 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labrijn AF, Janmaat ML, Reichert JM, et al. Bispecific antibodies: a mechanistic review of the pipeline. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019;18:585–608. 10.1038/s41573-019-0028-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goebeler M-E, Bargou RC. T cell-engaging therapies - BiTEs and beyond. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020;17:418–34. 10.1038/s41571-020-0347-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renner C, Jung W, Sahin U, et al. Cure of xenografted human tumors by bispecific monoclonal antibodies and human T cells. Science 1994;264:833–5. 10.1126/science.8171337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez M, Moon EK. Car T cells for solid tumors: new strategies for finding, infiltrating, and surviving in the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol 2019;10:128. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobold S, Pantelyushin S, Rataj F, et al. Rationale for combining bispecific T cell activating antibodies with checkpoint blockade for cancer therapy. Front Oncol 2018;8:285. 10.3389/fonc.2018.00285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saber H, Del Valle P, Ricks TK, et al. An FDA oncology analysis of CD3 bispecific constructs and first-in-human dose selection. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2017;90:144–52. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fucà G, Reppel L, Landoni E, et al. Enhancing chimeric antigen receptor T-cell efficacy in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26:2444–51. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellerman D. Bispecific T-cell engagers: towards understanding variables influencing the in vitro potency and tumor selectivity and their modulation to enhance their efficacy and safety. Methods 2019;154:102–17. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2018.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis SJ, van der Merwe PA. The kinetic-segregation model: TCR triggering and beyond. Nat Immunol 2006;7:803–9. 10.1038/ni1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minguet S, Schamel WWA. A permissive geometry model for TCR-CD3 activation. Trends Biochem Sci 2008;33:51–7. 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu X, Sereno AJ, Huang F, et al. Fab-based bispecific antibody formats with robust biophysical properties and biological activity. MAbs 2015;7:470–82. 10.1080/19420862.2015.1022694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bluemel C, Hausmann S, Fluhr P, et al. Epitope distance to the target cell membrane and antigen size determine the potency of T cell-mediated lysis by bite antibodies specific for a large melanoma surface antigen. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2010;59:1197–209. 10.1007/s00262-010-0844-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Stagg NJ, Johnston J, et al. Membrane-Proximal epitope facilitates efficient T cell synapse formation by Anti-FcRH5/CD3 and is a requirement for myeloma cell killing. Cancer Cell 2017;31:383–95. 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trinklein ND, Pham D, Schellenberger U, et al. Efficient tumor killing and minimal cytokine release with novel T-cell agonist bispecific antibodies. MAbs 2019;11:639–52. 10.1080/19420862.2019.1574521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staflin K, Zuch de Zafra CL, Schutt LK, et al. Target arm affinities determine preclinical efficacy and safety of anti-HER2/CD3 bispecific antibody. JCI Insight 2020;5. 10.1172/jci.insight.133757. [Epub ahead of print: 09 04 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandikian D, Takahashi N, Lo AA, et al. Relative target affinities of T-cell-dependent bispecific antibodies determine biodistribution in a solid tumor mouse model. Mol Cancer Ther 2018;17:776–85. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis SM, Wu X, Pustilnik A, et al. Generation of bispecific IgG antibodies by structure-based design of an orthogonal Fab interface. Nat Biotechnol 2014;32:191–8. 10.1038/nbt.2797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leaver-Fay A, Froning KJ, Atwell S, et al. Computationally designed bispecific antibodies using negative state repertoires. Structure 2016;24:641–51. 10.1016/j.str.2016.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pessano S, Oettgen H, Bhan AK, et al. The T3/T cell receptor complex: antigenic distinction between the two 20-kd T3 (T3-delta and T3-epsilon) subunits. Embo J 1985;4:337–44. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03634.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajendra Y, Peery RB, Hougland MD, et al. Transient and stable CHO expression, purification and characterization of novel hetero-dimeric bispecific IgG antibodies. Biotechnol Prog 2017;33:469–77. 10.1002/btpr.2414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nahta R, Hung M-C, Esteva FJ. The HER-2-targeting antibodies trastuzumab and pertuzumab synergistically inhibit the survival of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 2004;64:2343–6. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolt S, Routledge E, Lloyd I, et al. The generation of a humanized, non-mitogenic CD3 monoclonal antibody which retains in vitro immunosuppressive properties. Eur J Immunol 1993;23:403–11. 10.1002/eji.1830230216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demarest SJ, Glaser SM. Antibody therapeutics, antibody engineering, and the merits of protein stability. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel 2008;11:675–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayes PA, Hance KW, Hoos A. The promise and challenges of immune agonist antibody development in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018;17:509–27. 10.1038/nrd.2018.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone JD, Cochran JR, Stern LJ. T-Cell activation by soluble MHC oligomers can be described by a two-parameter binding model. Biophys J 2001;81:2547–57. 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75899-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franklin MC, Carey KD, Vajdos FF, et al. Insights into ErbB signaling from the structure of the ErbB2-pertuzumab complex. Cancer Cell 2004;5:317–28. 10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00083-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabat EAW, Perry T.T.;, Foeller H.M.;, et al. Sequences of proteins of immunological interest. Bethesda, MD: Diane Publishing, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rees AR. Understanding the human antibody repertoire. MAbs 2020;12:1729683. 10.1080/19420862.2020.1729683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamperschroer C, Shenton J, Lebrec H, et al. Summary of a workshop on preclinical and translational safety assessment of CD3 bispecifics. J Immunotoxicol 2020;17:67–85. 10.1080/1547691X.2020.1729902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Moreno BH, et al. Interferon receptor signaling pathways regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression. Cell Rep 2017;19:1189–201. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuch de Zafra CL, Fajardo F, Zhong W, et al. Targeting multiple myeloma with AMG 424, a novel Anti-CD38/CD3 bispecific T-cell-recruiting antibody optimized for cytotoxicity and cytokine release. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:3921–33. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vafa O, Trinklein ND. Perspective: designing T-cell Engagers with better therapeutic windows. Front Oncol 2020;10:446. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bacac M, Fauti T, Sam J, et al. A novel carcinoembryonic antigen T-cell bispecific antibody (CEA TCB) for the treatment of solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:3286–97. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slaga D, Ellerman D, Lombana TN, et al. Avidity-based binding to HER2 results in selective killing of HER2-overexpressing cells by anti-HER2/CD3. Sci Transl Med 2018;10. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat5775. [Epub ahead of print: 17 10 2018]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bacac M, Colombetti S, Herter S, et al. CD20-TCB with Obinutuzumab pretreatment as next-generation treatment of hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:4785–97. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rius Ruiz I, Vicario R, Morancho B, et al. p95HER2–T cell bispecific antibody for breast cancer treatment. Sci Transl Med 2018;10:eaat1445. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geiger M, Stubenrauch K-G, Sam J, et al. Protease-activation using anti-idiotypic masks enables tumor specificity of a folate receptor 1-T cell bispecific antibody. Nat Commun 2020;11:3196. 10.1038/s41467-020-16838-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.June CH, O'Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, et al. Car T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science 2018;359:1361–5. 10.1126/science.aar6711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiu D, Tavaré R, Haber L, et al. A PSMA-Targeting CD3 bispecific antibody induces antitumor responses that are enhanced by 4-1BB costimulation. Cancer Immunol Res 2020;8:596–608. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanmamed MF, Etxeberría I, Otano I, et al. Twists and turns to translating 4-1BB cancer immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med 2019;11. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax4738. [Epub ahead of print: 12 06 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tyrsin D, Chuvpilo S, Matskevich A, et al. From TGN1412 to TAB08: the return of CD28 superagonist therapy to clinical development for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34:45–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brinkmann U, Kontermann RE. The making of bispecific antibodies. MAbs 2017;9:182–212. 10.1080/19420862.2016.1268307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Claus C, Ferrara C, Xu W, et al. Tumor-Targeted 4-1BB agonists for combination with T cell bispecific antibodies as off-the-shelf therapy. Sci Transl Med 2019;11. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav5989. [Epub ahead of print: 12 06 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skokos D, Waite JC, Haber L, et al. A class of costimulatory CD28-bispecific antibodies that enhance the antitumor activity of CD3-bispecific antibodies. Sci Transl Med 2020;12. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw7888. [Epub ahead of print: 08 01 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu L, Seung E, Xu L, et al. Trispecific antibodies enhance the therapeutic efficacy of tumor-directed T cells through T cell receptor co-stimulation. Nat Cancer 2020;1:86–98. 10.1038/s43018-019-0004-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2021-002444supp001.pdf (5.7MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Raw data for each of the figures are available upon request.