Abstract

Given the mixed evidence on whether women’s economic and social empowerment is beneficial or not for reducing intimate partner violence (IPV), we explored the relationship between women’s empowerment and IPV risk. We analyzed data from baseline interviews with married women (n = 415) from the Intervention with Microfinance and Gender Equity (IMAGE) longitudinal study in rural South Africa. IMAGE combines a poverty-focused microfinance program with a gender-training curriculum. We fitted logistic regression models to explore associations between women’s economic situation/empowerment and IPV. For the multivariable logistic regression, we fitted three models that progressively included variables to explore these associations further. Women who reported “few to many times” for not earning enough to cover their business costs faced higher odds of past year physical and/or sexual violence (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 6.1, 1.7-22.3, p = .01). Those who received a new loan experienced higher levels of past year emotional (aOR = 2.8, 1.1-7.4, p = .03) and economic abuse (aOR = 6.3, 2.2-18.5, p = .001). Women who reported that partners perceived their household contribution as not important faced higher odds of past year economic abuse (aOR = 2.8, 1.0-7.8, p = .05). Women who reported joint decision-making or partner making sole reproductive decisions reported higher levels of past year physical and/or sexual violence (aOR = 5.7, 0.9-39.4, p = .07) and emotional abuse (aOR = 3.0, 0.9-10.2, p = .08). Economic stress and aspects of women’s empowerment, alongside established gender roles within marital relationships is associated with IPV risk in rural South Africa. Although improved economic conditions for women appears to be protective against physical and sexual IPV, associations between certain indicators of women’s economic situation, empowerment, and IPV are inconsistent. We need to consider complementary programming and all types of IPV in research, intervention, and policy, as different aspects of empowerment have varying associations with different types of IPV (physical, sexual, emotional, and economic abuse).

Keywords: women’s economic and social empowerment, economic situation, microfinance plus, intimate partner violence (IPV), South Africa

Introduction

Reducing poverty and achieving gender equality are essential components of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 1 and 5, respectively, and are fundamental for the development of communities and countries (UN, 2016). Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a clear indicator of gender inequality, where globally one in three women have reported experiencing physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime (Devries et al., 2013). In addition to causing injury or loss of life, IPV is associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including depressive symptoms and suicide (Green, Blattman, Jamison, & Annan, 2015) and increased risk of HIV/AIDS (Devries et al., 2013; Jewkes, 2002). In South Africa, the Demographic Health Surveillance survey reports 21% lifetime and 8% past year physical IPV and 6% lifetime and 2% past year sexual IPV, among ever-partnered women aged 18 years and older (“South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicator Report, Statistics South Africa,” 2016). Risk factors associated with IPV in South Africa include women’s poverty and low education, gender inequitable attitudes, and acceptability of IPV (Jewkes, Levin, & Penn-Kekana, 2002).

A common approach to addressing IPV has been through poverty alleviation. Donor agencies and governments target poor women in low-income countries with microfinance, savings groups or cash transfers (Hidrobo, Peterman, & Heise, 2016). These programs are based on the notion that women’s earnings and enterprise will reduce poverty, while advancing “empowerment,” defined broadly as improving the ability of women to access health, education, earning opportunities, rights, and political participation (Hidrobo et al., 2016). Microfinance uses a group-lending approach to increase people’s ability to generate income and secure livelihoods, and has been identified as a poverty reduction tool particularly among rural women (Dalal, Dahlström, & Timpka, 2013). Apart from some economic benefits, there is some evidence to suggest that it may be effective as a means for empowering women in particular, when combined with additional components to address gender norms (Gibbs, Jacobson, & Wilson, 2017; Kim et al., 2007). A 2006 cluster randomized trial in South Africa of the Intervention with Microfinance and Gender Equity (IMAGE) program, showed that a poverty reduction intervention combined with participatory gender training, achieved a 55% reduction (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.45, confidence interval [CI] = [0.23, 0.91]) in levels of past year physical and/or sexual partner violence relative to no program (Pronyk et al., 2006). However, microfinance only programs per se were not found to reduce risk for IPV (Green et al., 2015).

The role of women’s economic empowerment through poverty reduction interventions, such as microfinance had previously shown promising results within the development field (Duflo, 2011; Vyas & Watts, 2009). However, more recent trial evidence has shown a modest impact of microfinance only interventions on women’s empowerment (Angelucci, Karlan, & Zinman, 2015; Banerjee, Karlan, & Zinman, 2016). Furthermore, evaluation studies have also shown that such interventions do not necessarily result in decreases in women’s experience of IPV. There are mixed study results from different contexts demonstrating increases and decreases in IPV that warrant further exploration (Dalal et al., 2013; Raj et al., 2018; Vyas & Watts, 2009). Theoretically, women’s empowerment has the potential to have a positive or negative impact on their IPV risk; women with education, who contribute to household finances or have control over resources, may have higher household status and be less vulnerable to IPV (Vyas & Watts, 2009). Conversely, their economically and socially empowered position may challenge the established status quo and power balance with her partner and be associated with an increased risk of IPV, particularly if gender norms within the particular setting are unfavorable toward women (Buller et al., 2018; Schuler & Nazneen, 2018). This also aligns with the notion of social exchange theory for economic power in IPV that describes power as an interpersonal dynamic that can be expressed via decision-making dominance or the ability to engage in behaviors against a partner’s wishes (Emerson, 1976). In addition, design features related to the microfinance product, such as the type of loan, or high loan interest rates might also contribute to increases in IPV (Dalal et al., 2013). A review conducted by Hughes, Bolis, Fries, and Finigan (2015) draws on unpublished and published literature to provide evidence on how economic empowerment may decrease or increase IPV. In particular, the role of economic factors on women’s risk of IPV appears to be context-specific, complex and contingent on other factors such as household sociocultural context and socioeconomic characteristics, and particularities of empowerment processes, such as changing gender norms (Hughes et al., 2015).

We also acknowledge the ambiguity around the definition and measurement of empowerment, with a variety of indicators used to operationalize the concept that can make it difficult to draw conclusions (Kabeer, 1994; Kapiga et al., 2017). For this article, we use Vyas and Watts (2009) definition of economic empowerment as women’s access to resources through income-generating activities (either employment or credit programs). They also suggest additional measures of empowerment, such as a woman’s control over her resources or decision-making power (autonomy) or her contribution to household expenses (Vyas & Watts, 2009) that we explore in our analysis. Given the important health and development benefits of women’s empowerment, and the mixed evidence regarding which aspects may or may not be beneficial for addressing IPV, it is important to examine the relationship between economic and social empowerment and women’s risk of IPV. Using data from the IMAGE longitudinal study (described below), this article advances this line of inquiry by exploring these relationships in rural North West province, South Africa.

Method

IMAGE Intervention

This article is a secondary analysis of cross-sectional data collected from participants from the IMAGE longitudinal study. IMAGE combines a poverty-focused microfinance initiative implemented by the Small Enterprise Foundation (SEF), with a 10-session participatory curriculum of gender and HIV education known as Sisters for Life (SFL). It falls under the category of microfinance plus programs, that is, programs that combine access to microfinance services with complementary programs (e.g., gender training or training on health literacy). Loans are administered for the development of income generating activities with a group-lending model. Individual women run businesses, but groups of five women guarantee each other’s loans. SFL is put into practice during loan center meetings. It generally runs in parallel with the microfinance intervention by a separate training team. SFL has two phases: Phase 1 consists of ten 1-hr training sessions and covers topics including gender roles, cultural beliefs, relationships, communication, IPV, and HIV, and it aims to strengthen communication skills, critical thinking, and leadership. Because group-based learning can foster solidarity and collective action, there is a Phase 2 that encourages wider community mobilization to engage both young people and men in the intervention communities.

IMAGE Longitudinal Study: Study Setting, Sample, and Data Collection

Data collection was conducted from October to December 2016 in rural Mahikeng district in North West Province, South Africa, a site where SFL were delivering their 10-session participatory curriculum in 2016. Poverty is widespread in the area and unemployment rates are at 35.7% (and 47.1% among youth aged 15-34 years; Statistics South Africa, n.d.). The Mahikeng area had approximately 77 loan centers with a total of 2,399 loan recipients (around 460 loan groups in total with approximately five women in each group). The purpose of the IMAGE longitudinal study was to measure change in women’s experience of IPV over two time points and to collect data on individual and relationship level factors that are associated with IPV. We conducted this round of data collection after participants had received the microfinance loans and had just completed the SFL training. Because the original IMAGE intervention had evolved from a proof of concept to a scaled-up program, we were keen to explore how it was still affecting women’s lives after almost 10 years.

Women were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were 18 years or older and had been enrolled for a year or more in the Mahikeng branch of SEF loan centers where the microfinance plus program was recently completed. We recruited participants from loan meetings selecting a random sample of those attending the meeting and inviting them to participate. If women were unable or unwilling to stay, or refused to consent, the reason was documented. All women were provided with mobile phone airtime worth R50 (US$4) immediately after the interview. The total sample size of the trial was 860 women. Due to the nature of the variables under study in this article, this analysis includes only the subset of women who were married or living as married (n = 415).

The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee, and the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, provided ethical approval for the cohort study data collection and analysis.

Measurement Tools

Women completed structured, interviewer-administered, tablet-based questionnaires after the loan center meetings at an agreed time. Interviews were conducted in a private location by female interviewers trained on interviewing techniques, violence, and gender and ethical issues related to research on IPV. They were conducted in the participant’s preferred language—either the local language, seTswana or English. Questionnaires were translated into seTswana by bilingual researchers, checked for linguistic appropriateness, comprehension, and cultural relevance, and then back-translated from seTswana into English to ensure accuracy and fidelity to meaning.

Conceptual Framework and Variables

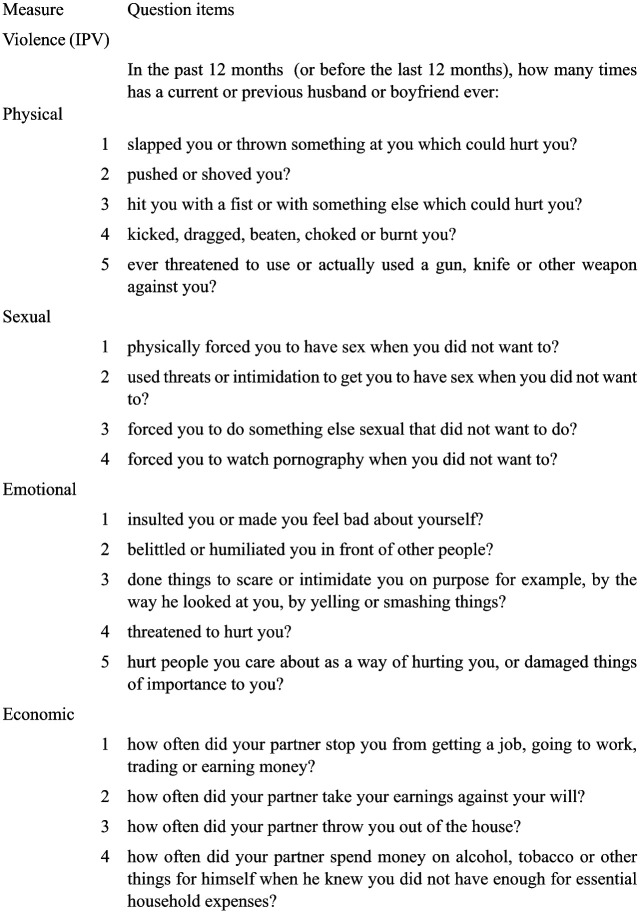

Our conceptual framework (Figure 1) draws upon previous literature and is influenced by the framework proposed by Buller et al. (2018). Our framework acknowledges the interplay between the internal qualities of the woman (power within self) and the dynamics within the relationship or household (power within relationship). We also recognize that the woman’s economic situation, such as her income contribution to the household, the characteristics of her business and loans can affect her experience of IPV. We hypothesize that the woman’s access to cash through the microfinance loans and the running of her business, and the gender training through SFL training results in enhanced self-confidence that can strengthen a woman’s ability to exit an abusive relationship or at least credibly threaten to leave, which might deter her husband from using violence. Furthermore, she is better able to negotiate the terms of the relationship and better able to assert her own preferences in the household and within the relationship. Depending on her partner’s reaction (not available in this dataset) to her increased resources and confidence, there could be an increase or decrease in IPV. Our framework recognizes the multiple aspects of empowerment, including empowerment focused on political participation, but for the purposes of this analysis, we have focused on the individual and relationship level.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework outlining pathway between household socioeconomic status, women’s economic situation and empowerment, and IPV for the IMAGE intervention.

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence; IMAGE = Intervention with Microfinance and Gender Equity.

Outcome variables

Violence and abuse measures

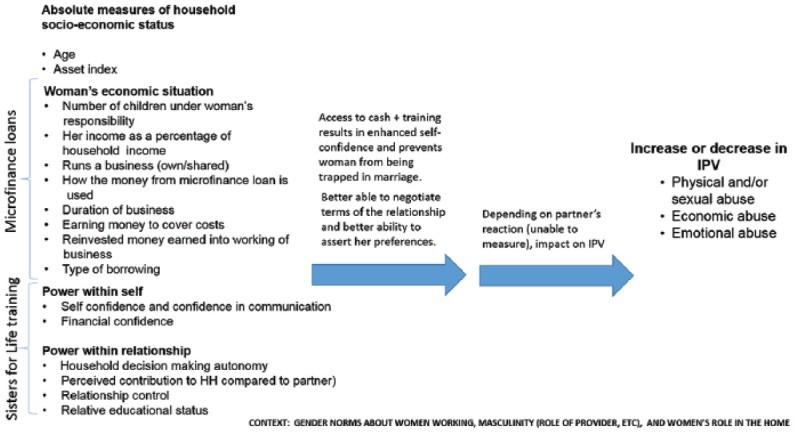

The primary outcome measures for this analysis are past year experience of physical and/or sexual violence and economic and emotional abuse. The physical and sexual violence and emotional abuse questions were adapted from the World Health Organization (WHO) Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence Against Women survey questions and translated to the local language, seTswana. Women currently married or currently living with a man as if married were asked about their experience of specific acts of sexual and physical violence and emotional abuse in the last 12 months. Economic abuse questions were adapted from the What Works violence prevention program (http://www.whatworks.co.za/about/about-what-works) in South Africa and consisted of questions on restrictive behaviors (e.g., “How often did your partner stop you from getting a job, going to work, trading or earning money?”) or self- interested behaviors (e.g., “How often did your partner spend money on alcohol, tobacco, or other things for himself when he knew you did not have enough for essential household expenses?”). Binary violence outcome variables were constructed with positive responses to one or more acts of (a) physical and/or sexual violence, (b) emotional abuse, and (c) economic abuse coded as 1 and all others coded as 0. Figure 2 provides the list of all the questions used to document physical, sexual violence, and emotional and economic abuse.

Figure 2.

List of questions used in this study for physical and sexual violence and emotional and economic abuse (a positive response to any act is coded as having experienced physical/sexual violence or emotional/economic abuse).

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

Exposure variables

The main exposure variables for this analysis are women’s economic situation and empowerment-related variables and were selected based on the literature and our conceptual framework:

Economic situation

We selected economic situation variables that were shown to be important determinants of IPV in other settings for the univariable analysis (Buller, Hidrobo, Peterman, & Heise, 2016; Jewkes, Dunkle, Nduna, & Shai, 2010). We selected the following variables: women’s highest level of education (up to secondary school, secondary school and above), her income as a percentage of household income (none, half or less, most of it, all of it), main person responsible for the business (self, shared responsibility), the duration of the business (up to 12 months, above 12 months), whether earning enough money to cover business costs (never, once, few to many times), proportion of money reinvested in the business (none, less than half, more than half), and type of loan borrowing (continuously, interrupted, or new loan in the year preceding the interview).

Empowerment measures

Drawing on concepts of empowerment outlined by Kim et al. (2007) from the original IMAGE study, and the social ecological framework of IPV (Heise, 2012), this article utilizes the approach of having internal qualities (“power within self”) and relational qualities (“power within relationship”).

Power within self includes the following measures: (a) self-confidence and confidence in communication (very confident, confident but needs encouragement, not confident) constructed from two questions—having the confidence to raise an opinion in public (e.g., at a school committee meeting) and confidence in communication (e.g., offering advice about family issues to neighbors), and (b) financial confidence measured with three questions on confidence to raise money alone to feed family for 4 weeks, to feed family for 4 weeks in the event of a crisis, and whether their ability to survive a crisis is better, same or worse than 2 years ago and were all coded as binary variables.

Power within relationship includes the following four measures: (a) first, the perceived contribution of the woman, as viewed by herself and her perception of how her contribution is viewed by her partner. The measure includes two items—how the woman views her contribution in terms of money and domestic duties in the household and how she perceives the partner views it; (b) second, the household decision-making measure that asked eight questions across a variety of topics, such as household purchases, family-related decisions, sexual and reproductive health decisions, with choice options focused on her making the decision, him making the decision, and both making the decision. The decision-making module used in this analysis had been used in other sub-Saharan countries (e.g., Burundi) in the context of a Village Loans Savings Associations (Iyengar & Ferrari, 2016). We used exploratory factor analysis to group the household decision-making questions into three categories: household economic purchases (four questions), family-related social decisions (two questions), and reproductive decisions (two questions). We analyzed each of these categories by who makes the decisions (she decides, they decide, he decides); (c) third, relationship power measure using the Sexual Relationship Power Scale (SRPS; 8-items, Cronbach’s α = .80). The SRPS is used to measure gender power equity and was previously shown to be associated with HIV incidence and partner violence among South African women (Dunkle et al., 2004a; Jewkes et al., 2010). Each item was assessed on a 3-point Likert-type scale and the measure was scored from 0 to 16 and categorized at the 50% cutoff level into a binary measure (high and low power) and; (d) fourth, relative educational status in the couple as a categorical measure. This measure compared both secondary educational levels for the women and her partner and responses grouped into the following categories: neither has any secondary education, only she has some, only he has some, and both have at least some secondary education.

The original questions for these measures are included in the appendix.

Other measures

We grouped women’s age into a categorical variable: below 35 years, 35 to 55 years, and above 55 years. For female-headed households, we created a binary variable, yes or no. We constructed the socioeconomic status using variables that capture living standards, such as household ownership of durable assets (e.g., TV, fridge) and infrastructure and housing characteristics (e.g., source of water, sanitation facility). We used principal component analysis on asset data to derive a socioeconomic status index, and then grouped households into categories reflecting different socioeconomic status levels (Vyas & Kumaranayake, 2006).

Statistical Analysis

We produced descriptive statistics on partner violence and abuse and sociodemographic, economic, and empowerment variables. Logistic regression models were fitted to obtain unadjusted odds ratios (with corresponding CIs) to explore the associations between sociodemographic and women’s economic situation/empowerment variables and each type of IPV. For the multivariable analysis, we included variables that showed some association in the unadjusted analysis: either through the magnitude of the odds ratios and/or whether the association showed statistical significance. We ran three models for physical and/or sexual violence, emotional abuse, and economic abuse using an approach in which we progressively added variables: Model 1 was adjusted for economic situation variables, Model 2 was adjusted for economic situation and “power within self” empowerment variables, Model 3 was adjusted for all variables in Models 1 and 2, as well as the “power within relationship” empowerment variables (see Table 2). Each of the three models was adjusted for age and socioeconomic status selected a priori as confounding variables. Age and socioeconomic status were tested as potential effect modifiers.

Table 2.

Sample Numbers and Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations Between Economic Variables, Empowerment Variables, and IPV and Abuse Among Married/Living Like Married Women (n = 415).

| Variables | Total n = 415 (%) | Unadjusted ORs (95% CI) |

Adjusted ORs (95% CI)

a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical/Sexual Violence (<12 months) | Emotional Abuse (<12 months) | Economic Abuse (<12 months) | Physical/Sexual Violence (<12 months) | Emotional Abuse (<12 months) | Economic Abuse (<12 months) | ||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| <35 | 61 (14.7) | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref | |

| 35-55 | 324 (78.3) | 0.42 [0.2, 0.9] | 0.40* [0.2, 0.8] | 1.06 [0.5, 2.4] | 0.33 † [0.1, 1.3] | 0.27 [0.1, 0.7] | 1.84 [0.5, 6.7] |

| 55+ | 29 (7.0) | 0.43 [0.1, 2.1] | 0.59 [0.2, 1.8] | 0.49 [0.1, 2.4] | 1.67 [0.1, 18.6] | 0.45** [0.1, 2.9] | 1.29 [0.1, 20.6] |

| Household socioeconomic position | |||||||

| Low | 116 (28.0) | ref | ref | ref | |||

| Medium | 139 (33.6) | 0.28** [0.1, 0.7] | 0.51* [0.3, 0.9] | 0.63 [0.3, 1.3] | Ref | ref | ref |

| High | 159 (38.4) | 0.46* [0.2, 1.1] | 0.52** [0.3, 0.9] | 0.54* [0.3, 1.1] | 0.12** [0.0, 0.5] | 0.56 [0.2, 1.4] | 0.74 [0.2, 2.2] |

| Economic situation | |||||||

| Female-headed household | |||||||

| No | 354 (85.3) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| Yes | 61 (14.7) | 1.32 [0.5, 3.3] | 0.70 [0.3, 1.6] | 1.16 [0.5, 2.5] | 1.05 [0.3, 4.1] | 0.25 [0.1, 0.8] | 1.22 [0.4, 3.8] |

| Number of children <18 years living at home (woman responsible for) b | |||||||

| None | 91 (21.9) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| 1 or 2 | 183 (44.1) | 1.17 [0.4, 3.2] | 0.87 [0.4, 1.8] | 2.78** [1.1, 6.9] | 1.89 [0.5, 7.6] | 1.40 [0.5, 3.6] | 5.01 [1.4, 17.6] |

| 3 or more | 141 (34.0) | 1.44 [0.5, 3.9] | 1.07 [0.5, 2.2] | 2.20 [0.8, 5.7] | 1.58 [0.4, 6.8] | 1.64 [0.6, 4.6] | 4.17* [1.2, 15.6] |

| Proportion of money contributed to household by woman | |||||||

| None | 141 (34.0) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| Half or less | 188 (45.3) | 1.78 [0.7, 4.5] | 1.06 [0.6, 1.9] | 0.71 [0.4, 1.3] | 2.00 [0.5, 7.7] | 1.35 [0.6, 3.2] | 0.92 [0.3, 2.3] |

| Most of it | 65 (15.7) | 2.68* [0.9, 7.7] | 1.10 [0.5, 2.5] | 0.62 [0.2, 1.5] | 1.52 [0.3, 7.5] | 1.19 [0.4, 4.0] | 0.53 [0.1, 2.1] |

| All of it | 21 (5.1) | 2.01 [0.4, 10.4] | 1.42 [0.4, 4.7] | 0.54 [0.1, 2.5] | 0.41 [0.0, 8.2] | 1.01 [0.1, 8.4] | 1.00 |

| Not earning enough to cover costs | |||||||

| Never | 182 (45.7) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| Once | 79 (19.8) | 1.16 [0.4, 3.5] | 1.06 [0.5, 2.3] | 0.74 [0.3, 1.7] | 1.94 [0.4, 8.5] | 1.28 [0.4, 3.6] | 0.70 [0.2, 2.4] |

| Few to many times | 137 (34.4) | 2.27* [0.9, 5.1] | 1.46 [0.8, 2.7] | 1.19 [0.6, 2.2] | 6.12** [1.7, 22.3] | 2.15 † [0.9, 5.0] | 1.27 [0.5, 3.2] |

| Proportion of money reinvested in business | |||||||

| None | 162 (40.8) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| Less than half | 202 (50.9) | 1.56 [0.7, 3.6] | 0.92 [0.5, 1.7] | 0.52* [0.3, 0.9] | 1.74 [0.5, 5.6] | 0.98 [0.4, 2.2] | 0.57 [0.2, 1.4] |

| More than half | 33 (8.3) | 3.03 † [0.9, 9.7] | 1.84 [0.7, 4.5] | 0.85 [0.3, 2.4] | 3.68 [0.6, 24.2] | 3.26 † [0.8, 12.8] | 0.91 [0.2, 4.1] |

| Type of borrowing | |||||||

| Continuously | 339 (81.9) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| Interrupted | 18 (4.2) | 1.51 [0.3, 6.9] | 1.31 [0.4, 4.7] | 0.50 [0.1, 3.8] | 2.16 [0.1, 52.3] | 1.05 [0.2, 8.9] | 0.55 [0.1, 10.1] |

| New loan | 57 (13.8) | 1.15 [0.4, 3.1] | 2.12** [1.1, 4.2] | 3.89** [2.1, 7.5] | 0.40 [0.1, 1.9] | 2.83** [1.1, 7.4] | 6.35** [2.2, 18.5] |

| Power within self | |||||||

| Self-confidence and confidence in communication | |||||||

| Very confident | 261 (62.3) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| Confident, but need encouragement | 95 (22.9) | 0.67 [0.3, 1.7] | 0.98 [0.5, 1.9] | 1.04 [0.5, 2.0] | 0.96 [0.2, 3.8] | 0.68 [0.3, 1.7] | 0.89 [0.3, 2.4] |

| Not confident | 59 (14.2) | 0.52 [0.2, 1.8] | 1.02 [0.5, 2.2] | 0.44 [0.2, 1.3] | 0.06* [0.0, 0.9] | 0.20** [0.1, 0.8] | 0.22 [0.1, 1.3] |

| Financial confidence | |||||||

| Confidence to raise money to feed family alone | |||||||

| Very confident | 288 (69.7) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| Moderately or not confident | 125 (30.3) | 1.35 [0.6, 2.8] | 1.44 [0.8, 2.5] | 1.25 [0.7, 2.3] | 0.75 [0.2, 3.5] | 2.06 [0.7, 5.7] | 1.03 [0.3, 3.5] |

| Confidence to raise money alone in the event of a crisis | |||||||

| Very confident | 217 (52.7) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | Ref | ref |

| Moderately or not confident | 195 (47.3) | 1.37 [0.7, 2.8] | 1.38 [0.8, 2.4] | 1.66 † [0.9, 2.9] | 0.79 [0.2, 2.8] | 0.89 [0.3, 2.3] | 0.79 [0.3, 2.3] |

| Ability to survive a financial crisis compared with 2 years ago | |||||||

| Better | 356 (87.0) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| Same or worse | 53 (13.0) | 1.70 [0.7, 4.3] | 1.60 [0.8, 3.3] | 1.74 [0.8, 3.7] | 1.17 [0.3, 4.9] | 1.41 [0.5, 3.9] | 1.47 [0.5, 4.8] |

| Power within relationship | |||||||

| Household dynamics | |||||||

| Perceived contribution viewed by partner | |||||||

| Woman’s contribution most important | 265 (65.6) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| Woman’s contribution somewhat/not important | 139 (34.4) | 1.90 † [0.9, 3.9] | 1.92** [1.1, 3.3] | 1.95** [1.1, 3.5] | 2.03 [0.5, 7.3] | 1.80 † [0.7, 4.3] | 2.82* [1.0, 7.8] |

| Perceived contribution viewed by self | |||||||

| Woman’s contribution most important | 308 (74.4) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| Woman’s contribution somewhat/not important | 106 (25.6) | 0.77 [0.3, 1.8] | 0.82 [0.4, 1.6] | 0.69 [0.3, 1.4] | 0.88 [0.2, 3.6] | 0.61 [0.2, 1.6] | 0.29* [0.1, 0.9] |

| Household decision-making | |||||||

| Household economic decisions | |||||||

| She decides | 130 (31.2) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| They decide | 131 (31.5) | 0.31 [0.1, 1.2] | 0.28** [0.1, 0.7] | 0.33** [0.1, 0.9] | 0.06** [0.0, 0.5] | 0.15** [0.0, 0.5] | 0.14** [0.0, 0.5] |

| He decides | 155 (37.3) | 2.05 † [0.9, 4.7] | 1.41 [0.8, 2.6] | 1.88* [1.0, 3.6] | 1.46 [0.4, 4.8] | 0.95 [0.4, 2.2] | 0.97 [0.3, 2.7] |

| Social decisions | |||||||

| She decides | 142 (35.8) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | Ref | ref |

| They decide | 159 (40.1) | 0.79 [0.4, 1.7] | 0.46** [0.2, 0.9] | 0.64 [0.3, 1.2] | 1.42 [0.4, 5.2] | 0.28** [0.1, 0.7] | 0.52 [0.2, 1.5] |

| He decides | 96 (24.2) | 0.60 [0.2, 1.6] | 0.57 [0.3, 1.1] | 0.79 [0.4, 1.6] | 0.18 [0.0, 0.9] | 0.18* [0.1, 0.5] | 0.41 [0.1, 1.4] |

| Reproductive decisions | |||||||

| She decides | 52 (13.1) | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref | ref |

| They decide | 153 (38.4) | 2.13 [0.5, 9.8] | 0.91 [0.4, 2.3] | 1.25 [0.4, 3.6] | 7.48** [1.0, 5.85] | 3.19 † [0.8, 11.7] | 3.69 [0.8, 17.9] |

| He decides | 193 (49.5) | 2.73 [0.6, 12.1] | 1.42 [0.6, 3.4] | 1.73 [0.6, 4.7] | 5.70* [0.8, 39.4] | 3.02 † [0.9, 10.2] | 3.62 † [0.8, 16.3] |

| Sexual Relationship Power Scale | |||||||

| High power | 120 (29.8) | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | Ref |

| Low power | 283 (70.2) | 15.2** [2.1, 11.2] | 3.30** [1.5, 7.2] | 6.38** [2.2, 18.1] | 10.83** [1.2, 9.6] | 2.17* [0.8, 5.8] | 10.19** [2.4, 43.2] |

| Relative educational status | |||||||

| Neither have any secondary education | 165 (40.0) | ref | ref | ref | ref | Ref | ref |

| Only she has some | 137 (33.2) | 1.10 [0.8, 4.7] | 1.24 [0.7, 2.3] | 1.32 [0.6, 2.7] | 1.64 [0.3, 4.5] | 0.68 [0.1, 8.0] | 0.80 [0.1, 13.1] |

| Only he has some | 25 (6.1) | 1.51 [0.3, 7.4] | 0.25 [0.1, 2.0] | 0.36 [0.1, 2.8] | 6.54 [0.6, 67.5] | 0.71 [0.1, 6.8] | 1.08 [0.1, 12.2] |

| Both have at least some | 85 (20.6) | 1.80 [0.7, 4.8] | 1.22 [0.6, 2.5] | 2.5** [1.2, 5.1] | 1.14 [0.2, 8.9] | 0.70 [0.0, 8.4] | 2.63 [0.2, 42.9] |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Statistical significance p value † between .1 and .05, *p < .05. **p < .01

In the adjusted analysis, the results for physical and/or sexual violence, economic abuse and emotional abuse have been adjusted for economic situation variables (Model 1), power within relationship (Model 2) variables, and power within self (Model 3) variables. The results presented are the final adjusted version for each type of IPV. All models have been adjusted for age and socioeconomic status variables.

Including children she has given birth to.

Results

Prevalence of IPV and Sample Characteristics

Among married women (n = 415), the prevalence of past year physical and/or sexual IPV was 7.9% (Table 1), past year economic abuse was 13.2%, and past year emotional abuse was 14.9%. Most women (78%) were in the 35- to 55-year age range and approximately 40% of women had no secondary schooling, and most lived in male-headed households (Table 2). Overall, 66% of women contributed to the household income, with 21% contributing more than half. Among women owning businesses, more than 90% were the sole owners. Almost 75% of businesses had been running for more than a year, close to 35% of women reported that a “few to many times” the business had not earned enough to cover costs, and only 8% reinvested half or more of their earnings back into the working of the business. In terms of loan borrowing, a majority (~80%) of women had been continuously borrowing in the year prior to the interview. Primary use of loan money was to build or maintain businesses and a small proportion used it for other expenses, such as school fees, food, and clothes or to help other family members.

Table 1.

Lifetime and Past Year Prevalence of Physical and Sexual Violence and Economic and Emotional Abuse Among All Women (n = 860) and Among Married/Living as Married Women (n = 415).

| All Women (n = 860) (%) |

Married/Living As Married (n = 415) (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime | Past 12 months | Lifetime | Past 12 months | |

| Physical violence | 128 (14.9) | 46 (5.4) | 62 (14.9) | 25 (6.0) |

| Sexual violence | 65 (7.6) | 25 (2.9) | 34 (8.2) | 18 (4.3) |

| Physical and/or sexual violence | 146 (16.9) | 57 (6.6) | 72 (17.3) | 33 (7.9) |

| Economic abuse | 123 (14.3) | 77 (9.0) | 67 (16.1) | 55 (13.2) |

| Emotional abuse | — | 96 (11.2) | — | 62 (14.9) |

Economic Situation and IPV

For the unadjusted and adjusted analyses, in households with a higher number of children (biological and other) living under the woman’s responsibility, women experienced higher levels of past year economic abuse (aOR = 4.2, 1.2-15.6, p = .01). Women who reported “few to many times” for not earning enough to cover the costs of running their business in the past month had six times higher odds of facing past year physical and/or sexual violence (aOR = 6.1, 1.7-22.3, p = .01). If they invested more than half of their earnings into their business, they experienced higher levels of recent physical and/or sexual violence (aOR = 3.7, 0.6-24.2, p = .1), though this result lacked statistical significance. Furthermore, if women’s proportion of contribution to the household in the past year was half or less, they faced higher odds of past year physical and/or sexual violence (aOR = 2.0, 0.5-7.7, p = .3) compared with those who did not contribute, but this was not statistically significant. Interestingly, if they reported receiving a new loan, they were more likely to face past year emotional abuse (aOR = 2.8, 1.1-7.4, p = .03) and economic abuse (aOR = 6.3, 2.2-18.5, p = .001).

Empowerment (“Power Within Self” and “Power Within Relationship”) and IPV

For the unadjusted and adjusted analyses, in the “power within self” category, women who reported less confidence in terms of communication with neighbors or those who reported feeling shy about public speaking, experienced lower levels of all types of violence. Associations with past year physical and/or sexual violence (aOR = 0.06, 0.01-0.9, p = .03) and emotional abuse (aOR = 0.2, 0.1-0.8, p = .02) were statistically significant. In terms of the “power within relationship” category, women who report low power on the SRPS face significantly higher odds of experiencing almost all forms of violence. Furthermore, women who reported that their partners perceived their contribution to household finances and chores as somewhat or not important have almost twofold higher odds of facing past year economic abuse (aOR = 2.8, 1.0-7.8, p = .05) than women who reported that their partner viewed their contribution as important. Furthermore, these women also had higher odds of facing past year physical and/or sexual abuse, but the results are not statistically significant. In terms of decision-making in the household, in the unadjusted analysis, women who report that the partner makes all household economic decisions experience higher levels of past year economic abuse (OR = 1.9, 1.0-3.6, p = .05). However, after adjusting for other empowerment and economic variables, this association does not remain (aOR = 0.97, 0.3-2.7, p = .9). In terms of reproductive decisions, women who report that they either make joint decisions or the partner makes such decisions report higher levels of past year physical and/or sexual violence (aOR = 5.7, 0.9-39.4, p = .07), emotional abuse (aOR = 3.0, 0.9-10.2, p = .08), as well as recent economic abuse (aOR = 3.6, 0.8-16.3, p = .2), although the evidence is weaker. There was overall no evidence in support of any effect modification of the relationship between economic situation and empowerment variables and IPV with age or socioeconomic status.

Discussion

We explored the relationship between women’s economic and social empowerment and their experience of IPV among a sample of married (or living as married) women, above the age of 18 years who were enrolled in a microfinance plus intervention in rural North West province, South Africa. These results suggest that alongside established gender roles within marital relationships, there are aspects of women’s economic situation, as well as certain aspects of women’s empowerment related to notions of “power within self” and “power within the relationship” that may increase IPV risk.

Our results show that in situations where households faced economic hardship, such as if the woman’s contribution to the household was below half of household income, or if they faced financial stress, such as when they were unable to cover the costs of running their business, there was a positive association with recent physical and/or sexual IPV. We postulate that this was because when women were unable to cover the costs of the business, it created significant financial stress for individuals and the households. Furthermore, this stress could lead to arguments over tight budgets and daily money to run the household (Buller et al., 2016). This aligns with findings, including on couples in Thailand that have demonstrated an association between current life stressors and the risk of experiencing and/or perpetrating IPV (Cano & Vivian, 2001; Gibbs, Corboz, & Jewkes, 2018). It is also consistent with qualitative and quantitative research from India that showed that household financial stressors increase women’s risk for IPV, and that impoverished women are more likely than middle and higher income women to work only to alleviate these financial stressors (Raj et al., 2018).

Furthermore, certain aspects of the microfinance programs related to the receipt of loans are positively associated with IPV. For example, women who reported receiving a new loan in the past year were more likely to experience emotional or economic abuse similar to other South African studies (Gibbs, Dunkle, & Jewkes, 2018; Jewkes, 2010). One possible reason is that when women begin to contribute to the household’s income, men may feel threatened as there is a change in their wives’ economic situation that can then lead to a male backlash and increased IPV, as men attempt to reassert control and their identity as the household provider or dominant decision maker (Buller et al., 2018). This aligns with the gender role strain theory (Conroy et al., 2015; Pleck, 1995) that suggests that men who perceive themselves as failing to live up to the provider role may experience negative psychological consequences and exhibit more aggression toward female partners (Pleck, 1995). It is interesting to note that new loan borrowing was not associated with physical and/or sexual violence. There are a number of potential reasons for this: emotional and economic abuse, while overlapping with physical IPV, are different constructs and as such may have slightly different drivers, related to control and power in the relationship. In addition, the relatively small sample size means that some of the adjusted odds ratios were not statistically significant in the final model.

Our results also show that women who reported low power on the SRPS—which is a series of questions focused on men’s controlling behaviors—faced higher levels of all types of IPV. The SRPS has been applied across many different populations and consists of two main domains: decision-making dominance and relationship control (McMahon, Volpe, Klostermann, Trabold, & Xue, 2015). This supports other research in South Africa that used the SRPS that showed that low levels of relationship power among women is associated with physical and sexual violence, as well as HIV infection and other risk factors for HIV, including unprotected sex, greater frequency of sex, multiple sexual partners, and transactional sex (Conroy et al., 2015; Dunkle et al., 2004b; Jewkes, Dunkle, Nduna, & Jama Shai, 2012; Ranganathan et al., 2016).

In terms of household dynamics, women who reported that their partners perceived their household contribution in terms of income or domestic chores as somewhat or not important had twice the odds of facing economic and emotional abuse. We have to be cautious in the interpretation of this result due to small sample sizes; however, we hypothesize that women whose partners did not display confidence in them, or show them appreciation, might also have partners who are prone to jealousy, and this might result in abuse. This may have implications for her sense of self-esteem and mental health. Research from the Middle East has shown that by isolating women, and by removing autonomy from women’s lives, emotional and economic abuse can impact on women’s mental health (Haj-Yahia, 2000). We also need to be cautious about the potential role that economic strengthening interventions, such as microfinance only and cash transfer only programs, might have on economic abuse. It is important that social empowerment complements such economic empowerment programs, to be truly transformative.

For household decision-making, the type of decision made affects whether the woman’s involvement in decision-making (sole or collaborative) influences her risk of IPV. For example, deviation from the dominant norms of male provision and authority was accepted in certain, but not all circumstances. Men might accept women working and making decisions that were related to domestic and household duties, but not around sexual and reproductive decisions. For sexual and reproductive decisions, both “they decide” and “he decides” categories have higher odds of experiencing IPV. This suggests that those that are in relationships governed by these gender norms (where men are more dominant in matters of sexual decision-making or perceived to be by women) are also those where men are more likely to perpetrate IPV. Hence, economic interventions that encourage couple communication, collaboration, and shared decision-making may be a promising strategy for increasing views about equality between intimate partners and promoting negotiation over violence during conflict, as reinforced by research from a violence prevention program in Rwanda (Stern, Heise, & McLean, 2018). The Rwandan study showed that within male and female partnerships when both partners share decision-making and contribute economically, this is perceived to have a positive effect on household development, relationship satisfaction, and conflict prevention (Stern et al., 2018).

Strengths and Limitations

The study strengths include a high response rate and extensive interviewer training, particularly around the IPV questions. Reporting bias around the IPV questions was further reduced by emphasizing research independence and confidentiality and use of standardized tools to measure IPV. Furthermore, we include a diverse sample of rural women of different age groups enrolled in a microfinance plus program in South Africa. Some limitations are noteworthy and need to be taken into account when interpreting the current results. First, we used cross-sectional data for this analysis; therefore, it is not possible to establish causality between women’s access to resources, women’s empowerment, and IPV. Our results can only be used to hypothesize potential pathways. There are also certain variables that could not be measured (e.g., men’s reaction to women working) that rules out the possibility of measuring pathways. In addition, data on when the women joined the microfinance programs were not collected in the study. Thus, the associations between the length of membership and occurrence of IPV could not be examined. Second, this study only targets women recipients of the microfinance plus (loans and gender training). Future programming and research need to include closer involvement of men and their perspectives, to improve our understanding of how increases in women’s power affects gender relations and diversify our sample. Third, the analysis only includes married or cohabiting women as the modules on household dynamics and decision-making modules were relevant for this group. There might be differences in how economic empowerment varies between married and unmarried women, and there is a need for future studies that are not restricted to just married women. Finally, the sample size was modest, limiting the precision with which we could estimate associations between economic/empowerment variables and IPV. Nevertheless, some sizable associations were still observed.

Conclusion

As Sabarwal, Santhya, and Jejeebhoy (2014) have demonstrated, relationships between specific dimensions of women’s economic situation and empowerment are complex, and there are still gaps in our understanding of what aspects of empowerment are beneficial depending on the social context (Sabarwal et al., 2014). This study supports findings from other settings that suggest that while improvements in women’s economic conditions in general appears to be protective against IPV, associations between women’s economic situation and empowerment indicators, such as contribution to household income and household decision-making and IPV are inconsistent. There is also now growing recognition that despite the initial promise of microfinance only programs as vehicles for economic empowerment, women receiving microfinance loans are more susceptible to IPV (Dalal et al., 2013). Therefore, additional studies in different settings are warranted to study the mechanisms by which economic stress associated with microfinance might be a contributing factor for IPV. Furthermore, this article clearly highlights the need for more microfinance plus programs, and demonstrates that different forms of empowerment have varying associations with different types of IPV (emotional, economic, physical, and sexual). The results also show the need to consider all types of IPV in research, intervention, and policy, particularly because they have distinctive impacts on health that need to be considered (Gibbs, Dunkle, & Jewkes, 2018). The association between emotional and economic abuse and other forms of IPV and health impacts on women are rarely considered, although there is now growing interest in emotional IPV, specifically around its consideration as an SDG indicator. Finally, it is important to work with both men and couples in economic interventions for IPV prevention to ensure sustained impacts on households.

Acknowledgments

The authors would especially like to thank the IMAGE participants for their contribution to this study, as well as staff at IMAGE, Small Enterprise Foundation and Social Surveys Africa. Without the time and generosity of both participants and field staff in South Africa, this work would not have been possible. For this, we are very grateful.

Author Biographies

Meghna Ranganathan is an assistant professor in the Gender Violence and Health Centre (GVHC) at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). Her research interests lie at the intersection between poverty, gender, and health, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

Louise Knight is a research fellow in the GVHC at the LSHTM. She is a social epidemiologist with interest in intervention research on violence prevention, HIV prevention and treatment, and adolescent sexual and reproductive health.

Tanya Abramsky is a research fellow within the GVHC at the LSHTM. Her research focuses on violence against women, its causes, consequences, and means of prevention.

Lufuno Muvhango is the project director of the Intervention with Microfinance and Gender Equity based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She has more than 15 years extensive experience in HIV prevention and gender-based violence projects.

Tara Polzer Ngwato is the Chief Executive Officer and Head of the Research at Social Surveys Africa, Johannesburg. She has more than 15 years of experience conducting research on social development with focus areas in conflict transformation and migration.

Mpho Mbobelatsi is the project manager and field researcher at Social Surveys Africa with extensive experience in field research and training on violence prevention and various development related projects in South Africa.

Giulia Ferrari is a research fellow at the GVHC. She has more than 10 years research experience in socioeconomic research on violence in sub-Saharan Africa and the United Kingdom and has worked as a consultant in the international and sustainable development fields.

Charlotte Watts is former Head of the Social and Mathematical Epidemiology Group and founder of the GVHC, in the Department for Global Health and Development. She has 20 years experience in international HIV and violence research and brings a strong multidisciplinary perspective to the complex challenge of addressing HIV and violence against women.

Heidi Stöckl is an associate professor and Director of the GVHC at LSTHM. In collaboration with the Mwanza Intervention Trials Unit in Mwanza, Tanzania, funded by an ERC Starting Grant, she is currently conducting the first longitudinal study on intimate partner violence among adult women in a low and middle income country.

Appendix

Empowerment Variables in Survey Tool

Power within self

1. Self confidence and confidence in communication

| 3.42 | People often feel shy about speaking in public. If you were at a community meeting (e.g., school committee), how confident are you that you could raise your opinion in public? (Discuss then code) | 1 = Very confident and often do

2 = Confident but would need to be encouraged to speak out 3 = Not confident at all/ scared to speak in public, and don’t 4 = Don’t know/not sure |

| 3.43 | Neighbors often have similar problems (e.g., around raising children). How confident do you feel about offering advice to your neighbor? | 1 = Very confident and often do

2 = Confident but rarely offer advice 3 = Not confident at all 4 = Don’t know/not sure |

2. Financial confidence

| 4.3 | How confident are you that you alone could raise enough money to feed your family for 4 weeks?—this could be, for example, by working, selling things that you own, or by borrowing money (from people you know or from a bank or money lender). | 1 = Very confident

2 = It would be possible/moderately confident 3 = Not confident at all 4 = Don’t know |

| 4.4 | In the event of a crisis (e.g., house fire) how confident are you that you alone could raise enough money to feed your family for 4 weeks? | 1 = Very confident

2 = It would be possible/moderately confident 3 = Not confident at all 4 = Don’t know |

| 4.5 | Is your ability to survive such a crisis better, same, or worse than 2 years ago? | 1 = Better

2 = Same 3 = Worse 4 = Don’t know |

Power within relationship

1. Household dynamics

| (a) Your partner | (b) Yourself | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1 | Think about the money that you bring into the household. How is your contribution viewed by | 1 = Yours is the most important contribution to the household

2 = You make some contribution to the household 3 = Your work does not seem very important at all 4 = Don’t know 5 = Not applicable because you don’t earn an income 96 = Not applicable for other reasons |

||

| 5.2 | Think about all the unpaid work you do to support the household, such as all the household chores you do (cooking, cleaning, fetching water). How is your contribution viewed by | 1 = Yours is the most important contribution to the household

2 = You make some contribution to the household 3 = Your work does not seem very important at all 4 = Don’t know 5 = Not applicable because you don’t earn an income 96 = Not applicable for other reasons |

2. Household decision-making in the household:

[section only asked if married or in long-term live-in relationship, that is, response to 2.6.1 = yes]

Different households have different ways of deciding on a variety of issues. We’d like to ask you about the process by which you and your spouse or partner make decisions.

| 6.1. I’m going to talk to you about a variety of issues. Please let me know how you and your spouse typically make decisions. When I say “spouse or husband,” I mean someone you are married to or are living with as if married. There is no right or wrong answer. We are just interested in how you make decisions on these different areas. (Circle the option which best represents the respondents answer. You do not need to read these options for each question but you may wish to provide them as a helpful way for the respondent to categorize who makes decisions) | |||||

| Responses for A’s | |||||

| (A1) I decide |

(A2) My spouse decides |

(A3) We usually agree to do what my husband wants/says |

(A4) I decide on some things my spouse decides on others |

(98) Other (please describe) |

(95) Not applicable (97) Refuse to answer |

| Question | Response (circle one) | ||||

| 6.1.iA. Who decides on how money you earn is spent? | A1 A2 A3 A4 | 98 | |||

| 6.1.iiA. Who decides on major household purchases? | A1 A2 A3 A4 | 98 | |||

| 6.1.iiiA. Who decides about purchases for daily household needs (food, fuel, etc.)? | A1 A2 A3 A4 | 98 | |||

| 6.1.ivA. Who decides about purchases on alcohol or cigarettes (include 95 not applicable)? | A1 A2 A3 A4 | 98 | |||

| 6.1.vA. Who decides when to visit your family or friends? | A1 A2 A3 A4 | 98 | |||

| 6.1.viA. Who decides when to visit to your spouse’s family or friends? | A1 A2 A3 A4 | 98 | |||

| 6.1.viiA. Who decides how many children you will have or whether to have more children? | A1 A2 A3 A4 | 98 | |||

| 6.1.viiiA. Who decides whether to have sex? | A1 A2 A3 A4 | 98 | |||

3. Relationship power

The next set of statements are about your relationship with your current or most recent main partner, please say for each if you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree:[Don’t READ OUT options each time]

| Relationship control scale | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| When he wants sex, he expects me to agree (not asked if 7.1 = 5). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| If I asked him to use a condom, he would get angry (not asked if 7.1 = 5). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| He won’t let me wear certain things. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| He has more to say than I do about important decisions that affect us. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| He tells me who I can spend time with. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| When I wear things to make me look beautiful, he thinks I may be trying to attract other men. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| He wants to know where I am all of the time. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| He lets me know I am not the only partner he could have. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

4. Relative educational status

Women’s educational status

| What is the highest grade you have completed at school? [do not read out—if do Grade 12 but failed matric, this is recorded as completed Grade 11] | 1 = Pre-school/Grade R

2 = Grade 1/Sub a/Class 1 3 = Grade 2/Sub b/Class 2 4 = Grade 3/Standard 1/Abet 1 5 = Grade 4/Standard 2/Abet 2 6 = Grade 5/Standard 3/Abet 2 7 = Grade 6/Standard 4/Abet 3 8 = Grade 7/Standard 5/Abet 3 9 = Grade 8/Standard 6/Abet 3 10 = Grade 9/Standard 7/Abet 3 11 = Grade 10/Standard 8/Ntc 1 12 = Grade 11/Standard 9/Ntc 2 13 = Grade 12/Standard 10/Ntc 3 14 = Further studies incomplete 15 = Diploma/other post school completed 16 = Further degree completed 96 = Don’t know 97 = Refused to answer If = 13 continue to 2.5a otherwise skip to 2.6 |

Men’s educational status

| What is the highest level of education that he completed? SELECT ONE |

1 = Never went to school

2 = Primary incomplete 3 = Primary complete 4 = Secondary incomplete 5 = Secondary (Form I-IV) 6 = Secondary (Form V-VI) 7 = College training after primary/secondary school and before university 8 = University 9 = Don’t know |

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: an anonymous donor provided funds for the data collection, and we completed the analysis through an ESRC Secondary Data Analysis Initiative Global Challenges Research Fund (grant number: ES/P003176/1). Meghna Ranganathan is a member of the STRIVE consortium, which is funded by UK aid from the Department for International Development. However, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the department’s official policies.

ORCID iDs: Meghna Ranganathan  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5827-343X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5827-343X

Giulia Ferrari  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1670-4905

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1670-4905

Data Availability: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they contain participant identification numbers but might be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Angelucci M., Karlan D., Zinman J. (2015). Microcredit impacts: Evidence from a randomized microcredit program placement experiment by Compartamos banco. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7, 151-182. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A., Karlan D., Zinman J. (2016). Six randomized evaluations of microcredit: Introduction and further steps. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 1-21. [Google Scholar]

- Buller A. M., Hidrobo M., Peterman A., Heise L. (2016). The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach? A mixed methods study on causal mechanisms through which cash and in-kind food transfers decreased intimate partner violence. BMC Public Health, 16(1), Article 488. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3129-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buller A. M., Peterman A., Ranganathan M., Bleile A., Hidrobo M., Heise L. (2018). A mixed methods review of cash transfers and intimate partner violence in low and middle-income countries. World Bank Research Observer. The World Bank Research Observer, 33(2), 218-258. doi:10.1093/wbro/lky002 [Google Scholar]

- Cano A., Vivian D. (2001). Life stressors and husband-to-wife violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6, 459-480. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy A. A., McGrath N., van Rooyen H., Hosegood V., Johnson M. O., Fritz K., . . . Darbes L. (2015). Power and the association with relationship quality in South African couples: Implications for HIV/AIDS interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 16, 461-470. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.02.014.A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal K., Dahlström O., Timpka T. (2013). Interactions between microfinance programmes and non-economic empowerment of women associated with intimate partner violence in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 3, 13-15. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries K. M., Mak J. Y. T., Garcia-Moreno C., Petzold M., Child J. C., Falder G., . . . Watts C. H. (2013). The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science, 340, 1527-1528. doi: 10.1126/science.1121400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duflo E. (2011). Women’s empowerment and economic development (NBER Working Paper Series). doi: 10.3386/w17702 [DOI]

- Dunkle K. L., Jewkes R. K., Brown H. C., Gray G. E., McIntryre J. A., Harlow S. D. (2004. a). Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. The Lancet, 363, 1415-1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle K. L., Jewkes R. K., Brown H. C., Gray G. E., McIntryre J. A., Harlow S. D. (2004. b). Transactional sex among women in Soweto, South Africa: Prevalence, risk factors and association with HIV infection. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 1581-1592. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 335-362. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs A., Corboz J., Jewkes R. (2018). Factors associated with recent intimate partner violence experience amongst currently married women in Afghanistan and health impacts of IPV: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health, 18(1), Article 593. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5507-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs A., Dunkle K., Jewkes R. (2018). Emotional and economic intimate partner violence as key drivers of depression and suicidal ideation: A cross-sectional study among young women in informal settlements in South Africa. PLoS ONE, 13(4), Article e0194885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs A., Jacobson J., Wilson A. K. (2017). A global comprehensive review of economic interventions to prevent intimate partner violence and HIV risk behaviours. Global Health Action, 10(Suppl. 2), Article 1290427. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1290427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green E. P., Blattman C., Jamison J., Annan J. (2015). Women’s entrepreneurship and intimate partner violence: A cluster randomized trial of microenterprise assistance and partner participation in post-conflict Uganda (SSM-D-14-01580R1). Social Science & Medicine, 133, 177-188. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haj-Yahia M. M. (2000). The incidence of wife abuse and battering and some sociodemographic correlates as revealed by two national surveys in Palestinian society. Journal of Family Violence, 15, 347-374. [Google Scholar]

- Heise L. (2012). Determinants of partner violence in low and middle-income countries: Exploring variation in individual and population-level risk. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Retrieved from http://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/682451/1/560822.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hidrobo M., Peterman A., Heise L. (2016). The effect of cash, vouchers and food transfers on intimate partner violence: Evidence from a randomized experiment in Northern Ecuador. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 8, 284-303. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C., Bolis M., Fries R., Finigan S. (2015). Women’s economic inequality and domestic violence: Exploring the links and empowering women. Gender & Development, 23, 279-297. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2015.1053216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar R., Ferrari G. (2016). Comparing economic and social interventions to reduce intimate partner violence: Evidence from central and Southern Africa. In Sebastian E., Simon J., Weil D. N. (Eds.), National bureau of economic research (Vol. II, pp. 165-214). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/chapters/c13379 [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. K. (2002). Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. The Lancet, 359, 1423-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. K. (2010). Emotional abuse: A neglected dimension of partner violence. The Lancet, 376, 851-852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61079-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. K., Dunkle K., Nduna M., Shai N. J. (2010). Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort study. The Lancet, 376, 41-48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. K., Dunkle K., Nduna M., Shai N. J. (2012). Transactional sex and HIV incidence in a cohort of young women in the stepping stones trial. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 3(5). doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. K., Levin J., Penn-Kekana L. (2002). Risk factors for domestic violence: Findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Social Science & Medicine, 55, 1603-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N. (1994). Reversed realities: Gender hierarchies in development thought. London, England: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Kapiga S., Harvey S., Muhammad A. K., Stöckl H., Mshana G., Hashim R., . . . Watts C. (2017). Prevalence of intimate partner violence and abuse and associated factors among women enrolled into a cluster randomised trial in northwestern Tanzania. BMC Public Health, 17(1), Article 190. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4119-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. C., Watts C. H., Hargreaves J. R., Ndhlovu L. X., Phetla G., Morison L. A., . . . Pronyk P. (2007). Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women’s empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1794-1802. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.095521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon J. M., Volpe E. M., Klostermann K., Trabold N., Xue Y. (2015). A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the Sexual Relationship Power Scale in HIV/AIDS research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 267-294. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0355-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck J. H. (1995). The gender role strain paradigm: An update. In Levant R. F., Pollack W. (Eds.), A new psychology of men (pp. 164-206). New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Pronyk P. M., Hargreaves J. R., Kim J. C., Morison L., a Phetla G., Watts C., . . . Porter J. D. (2006). Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: A cluster randomised trial. The Lancet, 368, 1973-1983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A., Silverman J. G., Klugman J., Saggurti N., Donta B., Shakya H. B. (2018). Longitudinal analysis of the impact of economic empowerment on risk for intimate partner violence among married women in rural Maharashtra, India. Social Science & Medicine, 196, 197-203. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan M., Heise L., Pettifor A., Silverwood R. J., Selin A., MacPhail C., . . . Watts C. (2016). Transactional sex among young women in rural South Africa: Prevalence, mediators and association with HIV infection. Journal of the International AIDS, 19(1), Article 20749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabarwal S., Santhya K. G., Jejeebhoy S. J. (2014). Women’s autonomy and experience of physical violence within marriage in rural India: Evidence from a prospective study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 332-347. doi: 10.1177/0886260513505144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler S. R., Nazneen S. (2018). Does intimate partner violence decline as women’s empowerment becomes normative? Perspectives of Bangladeshi women. World Development, 101, 284-292. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South Africa demographic and health survey 2016: Key indicator report, statistics South Africa. (2016). Pretoria, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. (n.d.). Mafikeng statistics. Retrieved from http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=993&id=mafikeng-municipality

- Stern E., Heise L., McLean L. (2018). The doing and undoing of male household decision-making and economic authority in Rwanda and its implications for gender transformative programming. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 20(9), 976-991. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1404642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). (2016). The sustainable development goals report. New York, NY: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas S., Kumaranayake L. (2006). Constructing socio-economic status indices: How to use principal components analysis. Health Policy and Planning, 21, 459-468. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas S., Watts C. (2009). How does economic empowerment affect women’s risk of intimate partner violence in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published evidence. Journal of International Development, 21, 577-602. [Google Scholar]