Abstract

Excessive alcohol intake is an established risk factor for chronic liver disease. At the same time, moderate alcohol intake appears to reduce cardiovascular morbidity. Accordingly, recommendations for alcohol intake in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), who are at increased risk for liver-related and cardiovascular events, are a point of debate. Some studies have shown beneficial effects of alcohol on cardiovascular and overall mortality in this specific subset of patients. Nonetheless, even light alcohol intake appears to aggravate liver disease and increase the risk of hepatocellular cancer. Therefore, patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or advanced fibrosis should be advised against consuming alcohol. On the other hand, only light alcohol consumption (<10 g/day) might be permitted in patients without significant hepatic fibrosis, provided that they are carefully followed-up. As the research field focusing on NAFLD keeps widening, more prospective studies regarding this specific subject are expected, and may provide a basis for less ambiguous recommendations.

Keywords: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, alcohol, cardiovascular disease, hepatocellular cancer, fibrosis

Introduction

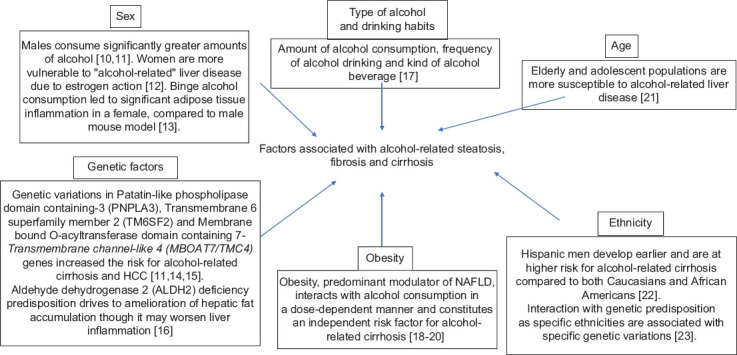

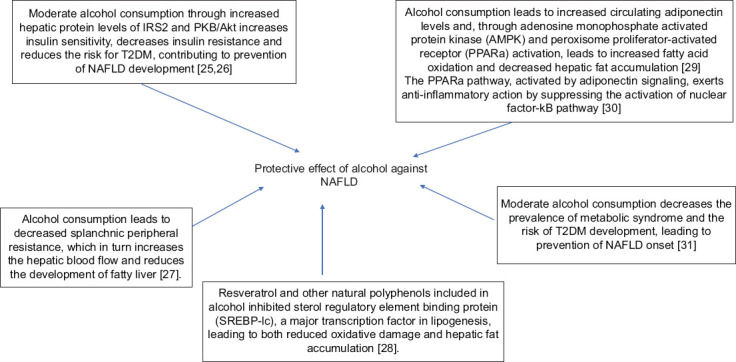

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease. It affects as many as one-fourth of the general population worldwide, being more frequent in patients with metabolic syndrome (MetS) or its components than in the general population [1]. NAFLD diagnosis requires that the patient does not exhibit daily alcohol consumption of ≥30 g for men or ≥20 g for women [2]. NAFLD can progress from isolated steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which encompasses, besides steatosis, ballooning hepatocellular injury, inflammation and liver fibrosis, and might evolve to cirrhosis or even to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [3,4]. Patients with NAFLD are at high risk for cardiovascular disease and are more likely to die from coronary heart disease than hepatic disease; indeed, cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death in this population [5-7]. Modification of cardiovascular risk factors includes lifestyle interventions, such as regular physical exercise, and weight loss [8]. In addition, moderate alcohol consumption also appears to reduce the risk of coronary heart disease [9]. On the other hand, excessive alcohol consumption is an established risk factor for liver disease, with various cofactors influencing liver disease development in patients with excessive alcohol use (Fig. 1) [10-23]. However, accumulating data suggest that moderate alcohol intake might reduce NAFLD incidence [24]; the mechanisms possibly involved (studied in both animal and human models) are illustrated in Fig. 2 [25-31]. Taking these conflicting effects of alcohol into account, it is of great interest to elucidate the role of light and moderate alcohol consumption in NAFLD, in order to counsel these patients regarding alcohol use. There have been relatively recent reviews regarding the subject in question [32,33], but because of the constant publication of new studies on the subject, many critical studies are not included in these reviews, which significantly alter prior beliefs regarding alcohol use in NAFLD. This narrative review aims to summarize recent developments in this field and encapsulate how these developments affect recommendations regarding alcohol consumption in NAFLD.

Figure 1.

Individual phenotypic and genetic factors associated with alcohol-induced liver steatosis, fibrosis and cirrhosis NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of the beneficial impact of moderate alcohol consumption on NAFLD development NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus

Literature search

To find relevant studies, we conducted a thorough search in the PubMed, Google Scholar and Cochrane Library databases through December 2020. Search terms included “NAFLD”, “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease”, “hepatic steatosis”, “fatty liver”, “alcohol”, and “ethanol”. We also searched the references of selected studies and relevant reviews for unidentified studies. The studies that were included analyzed outcomes in patients with NAFLD (or NAFLD incidence) with regard to levels of alcohol consumption.

Does alcohol prevent the development of fatty liver?

The common histopathological features shared between NAFLD and alcoholic liver disease (ALD) [34], as well as the fact that one is frequently misclassified as the other [35], can be partially explained by the shared mechanisms contributing to the emergence of both diseases [36,37]. However, only one study showed that alcohol consumption increases the risk of NAFLD. Long et al evaluated the correlation between the presence of hepatic steatosis (assessed by computed tomography) and alcohol consumption in 2475 participants of the Framingham study [38], after excluding heavy drinkers. The number of alcoholic drinks consumed per week was an independent predictor of steatosis (odds ratio [OR] 1.15, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02-1.29.

In contrast, several studies support the notion that moderate alcohol consumption can have a protective effect against NAFLD development. In a large study, Hashimoto et al evaluated 5437 healthy Japanese individuals on a regular checkup program for over a decade [39]. The hazard ratios (HR) for newly diagnosed fatty liver in subjects with light (40-140 g/week) and moderate (140-280 g/week) alcohol consumption compared with those with no or minimal alcohol consumption (<40 g/week) were 0.72, 95%CI 0.60-0.86, and 0.69, 95%CI 0.57-0.84 (P<0.001), respectively, in men. In women, alcohol consumption was not associated with the incidence of NAFLD. Another study in Japanese men reported similar findings; light (40-140 g/week) and moderate alcohol intake (140-280 g/week) were associated with a reduced risk for fatty liver development, compared to null drinking consumption (OR 0.82, 95%CI 0.68-0.99 and 0.75, 95%CI 0.61-0.93, respectively) [40]. Interestingly, Hiramine et al showed that not only light (<20 g/day, OR 0.71, 95%CI 0.59-0.86) and moderate (20-60 g/day, OR 0.55, 95%CI 0.45-0.67), but also heavy (>60 g/day, OR 0.44, 95%CI 0.32-0.62) alcohol drinking was associated with decreased odds for fatty liver compared to non-drinkers in Japanese men [41], confirmed by another study from Asia [42]. In accordance with the studies mentioned above, Hamaguchi et al performed a cross-sectional study on 18,571 Japanese individuals. They reported that any level of alcohol consumption—light (40-140 g/week, OR 0.69, 95%CI 0.6-0.79), moderate (140-280 g/week, OR 0.72, 95%CI 0.63-0.83) and excessive (>280 g/week, OR 0.74, 95%CI 0.64-0.85) compared with no or minimal (<40 g/week) was associated with decreased odds for fatty liver in men. In contrast, in women, light (OR 0.54, 95%CI 0.34-0.88) and moderate (OR 0.43, 95%CI 0.21-0.88) alcohol intake decreased the likelihood of the presence of fatty liver [43]. Finally, a recent study by Chang et al showed that light (<10 g/day) and moderate (10-20 g/day) drinking were independently associated with a lower incidence of NAFLD compared to non-drinkers (HR 0.93, 95%CI 0.90-0.95, and HR 0.90, 95%CI 0.87-0.92, respectively) [44]. However, light and moderate drinkers were more susceptible to developing NAFLD with significant fibrosis (FIB-4 >1.3) compared to non-drinkers (HR 1.15, 95%CI 1.04-1.27, and HR 1.49, 95%CI 1.33-1.66, respectively).

Several studies also suggest that more frequent alcohol consumption might also decrease the risk of NAFLD. Hiramine et al [41] reported that the prevalence of fatty liver was negatively correlated with alcohol drinking (OR 0.62, 95%CI 0.53-0.71 for ≥21 days/month vs. ≤10 days/month). Similarly, in the cross-sectional study by Moriya et al, an inverse association between the prevalence of fatty liver and alcohol consumption frequency was observed in men [45]. In women, drinking <20 g alcohol during 1-3 days/week was also associated with a reduced prevalence of fatty liver [45]. A longitudinal study from the same group in 5297 Japanese individuals showed that the frequency of alcohol consumption was inversely associated with fatty liver in men (OR 0.81, 95%CI 0.71-0.93, OR 0.68, 95%CI 0.58-0.78, and OR 0.64, 95%CI 0.56-0.73, for 1-3 days/week, 4-6 days/week and daily, respectively); in women, daily alcohol consumption was also associated with a lower incidence of fatty liver (OR 0.60, 95%CI 0.40-0.90) [46]. In another study from Japan, Sogabe et al assessed 1055 men with MetS and NAFLD and reported that the prevalence of NAFLD was lower in light drinkers (consuming <20 g of alcohol/drinking day) than in non-drinkers [47]. Finally, a meta-analysis by Sookoian et al confirmed the findings of previous studies, showing that moderate consumption (<40 g/day) was associated with lower odds of NAFLD (OR 0.68, 95%CI 0.58-0.81) and NASH (OR 0.5, 95%CI 0.34-0.74) development, compared to non-drinkers [48].

It should be emphasized that most of the studies that evaluated the impact of alcohol consumption on the incidence of fatty liver were performed in Asian and mostly Japanese populations. Therefore, the generalizability of their findings in non-Asian subjects is an open question. Also, it should be noted that many of these studies use definitions of moderate alcohol consumption that are nowadays considered to be equivalent to alcohol-related liver disease. Studies investigating the effect of alcohol consumption on the development of NAFLD are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies investigating the effect of alcohol consumption on the development of NAFLD

Is alcohol associated with less severe histological lesions in NAFLD patients?

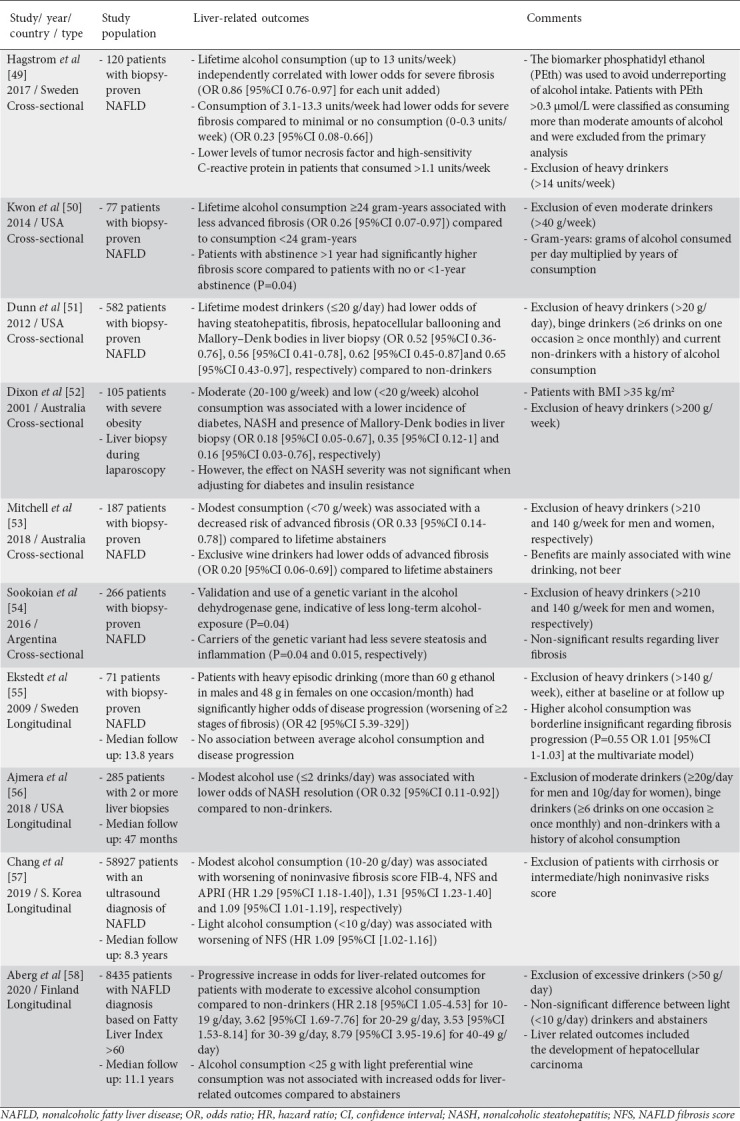

To evaluate the impact of alcohol consumption on the severity of hepatic fibrosis in patients with NAFLD, Hagström et al prospectively studied 120 patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD and evaluated their lifetime alcohol use using questionnaires [49]. After adjusting for physical activity, and soft drink and coffee consumption, the odds for severe fibrosis decreased for each additional alcohol unit consumed (i.e., 12 grams of alcohol) for up to a maximum of 13 drinks/week (OR 0.86, 95%CI 0.76-0.97); moreover, subjects in the top quartile of alcohol consumption (3.1-13.3 alcohol units/week) had the lowest risk for severe fibrosis (OR 0.23, 95%CI 0.08-0.66). Furthermore, patients who consumed alcohol more than the median (1.1 units of alcohol/week) had lower levels of markers of subclinical inflammation (tumor necrosis factor and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) and higher total cholesterol levels compared with those who consumed lower amounts of alcohol [49]. In accordance with these findings, a study from the USA in 77 patients with histologically confirmed NAFLD showed that those with overall lifetime alcohol use ≥24 gram-years had less advanced fibrosis, lower percent total body fat and lower total cholesterol levels compared with those who had consumed <24 gram-years of alcohol [50]. Gram-years were calculated by multiplying the amount of alcohol consumed per day and consumption duration in years. Notably, patients still drinking alcohol or abstinent for ≤1 year had lower fibrosis scores and total body fat percent than patients who abstained from alcohol for >1 year. Notably, in a cross-sectional study that included 582 patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD—331 modest drinkers (≤20 g of alcohol daily) and 251 lifetime non-drinkers—moderate drinkers, compared with non-drinkers, had lower odds of having steatohepatitis, fibrosis, hepatocellular ballooning and Mallory-Denk bodies on liver biopsy (OR 0.52, 95%CI 0.36-0.76, OR 0.56, 95%CI 0.41-0.78, OR 0.62, 95%CI 0.45-0.87, and OR 0.65, 95%CI 0.43-0.98, respectively) [51]. Consistently, a cross-sectional study from Australia reported that low (<20 g/week) and moderate (20-100 g/week) consumption was associated with a lower risk for diabetes mellitus (OR 0.18, 95%CI 0.05-0.67), NASH (OR 0.35, 95%CI 0.12-1) and Mallory bodies in liver biopsy (OR 0.16, 95%CI 0.03-0.76) compared to no consumption. However, after adjustment for diabetes or insulin resistance index, alcohol consumption’s beneficial effect on NASH severity was not confirmed [52]. Finally, Mitchell et al reported that patients with NAFLD who consumed modest (<70 g/week) and moderate (≥70 g/week) amounts of alcohol, compared to lifetime non-drinkers, had lower ballooning and fibrosis scores [53]. Notably, only modest alcohol consumption was associated with lower odds for advanced fibrosis (OR 0.33, 95%CI 0.14-0.78) after adjusting for age, diabetes, body mass index (BMI), homeostatic model assessment, sex, and overall lifetime alcohol consumption, whereas binge alcohol drinking was not associated with a lower fibrosis stage [53]. It should be mentioned that patients who consumed only wine, compared to lifetime non-consumers, had a lower fibrosis stage and risk for severe fibrosis (OR 0.20, 95%CI 0.06-0.69), whereas this protective effect was not observed in exclusive beer drinkers.

Given the limitations of self-reported alcohol consumption, Sookoian et al used a genetic variant (rs1229984 A;G) in the alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH1B) gene as a proxy of long-term alcohol exposure and evaluated its association with the severity of histological lesions in patients with NAFLD [54]. Carriers of this polymorphism were found to consume lower amounts of alcohol than non-carriers. In contrast to the aforementioned studies’ findings, carriers of this polymorphism had less severe steatosis and inflammation than non-carriers, whereas the fibrosis stage did not differ between the 2 groups. Moreover, several studies reported that increased alcohol consumption is associated with liver disease progression in patients with NAFLD. Ekstedt et al evaluated 71 patients with NAFLD diagnosed by liver biopsy [55]. The authors divided the patients according to disease progression as having insignificant or significant changes in liver biopsy (significant defined as worsening of ≥2 stages of fibrosis). After a mean follow up of 13.8 years, reported heavy episodic drinking was independently associated with significant liver biopsy changes. In another study, which included 285 patients with NASH diagnosed by liver biopsy, those who abstained from alcohol at baseline experienced more significant reductions in steatosis grade and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels compared to modest drinkers (1 or 2 drinks on a typical drinking day) after a mean follow up of 47 months, while modest drinkers also had lower odds of NASH resolution (OR 0.32, 95%CI 0.11-0.92). Interestingly, when considering changes in drinking habits, consistent non-drinkers had a more pronounced reduction in steatosis grade and higher odds of NASH resolution compared to consistent modest drinkers [56]. In a large study in 58,927 Korean patients with NAFLD and low fibrosis scores—NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS), FIB-4 and AST-to-platelet ratio index (APRI)—followed-up for a median of 8.3 years, modest alcohol drinking (10-20 g/day) was independently associated with worsening of all noninvasive fibrosis scores (HR 1.29, 95%CI 1.18-1.40, HR 1.31, 95%CI 1.23-1.40, and HR 1.09, 95%CI 1.01-1.19 for FIB-4, NFS and APRI, respectively). In addition, light alcohol consumption (0-10 g/day) was also independently associated with worsening of NFS (HR 1.09, 95%CI 1.02-1.16) [57]. Finally, a study by Aberg et al evaluated the risk of advanced liver disease in 8345 Finnish patients with NAFLD diagnosed with the Fatty Liver Index with respect to their drinking habits. Patients with alcohol consumption >10 g/day were more susceptible to developing advanced liver disease and the HR was dose-dependent (10-19 g, HR 2.18, 95%CI 1.05-4.53; 20-29 g, HR 3.62, 95%CI 1.69-7.76) [58]. Interestingly, this correlation was not significant in patients drinking mainly wine in amounts <25 g/day.

Studies in this section are divided into 2 groups: studies investigating the effect of alcohol consumption on NAFLD severity at diagnosis, and studies investigating alcohol consumption on NAFLD progression. The latter studies provide more trust-worthy data because of the patients’ follow up and share an identical conclusion: even modest consumption (>10 g/day) is tied to worse liver-related outcomes. However, light consumption (<10 g/day) was not associated with worse liver-related outcomes in most studies and was associated with lower odds for significant fibrosis in most studies investigating disease severity at diagnosis. Studies evaluating the effect of alcohol on the severity of hepatic disease in NAFLD are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies investigating the effect of alcohol consumption on the severity of hepatic disease in NAFLD

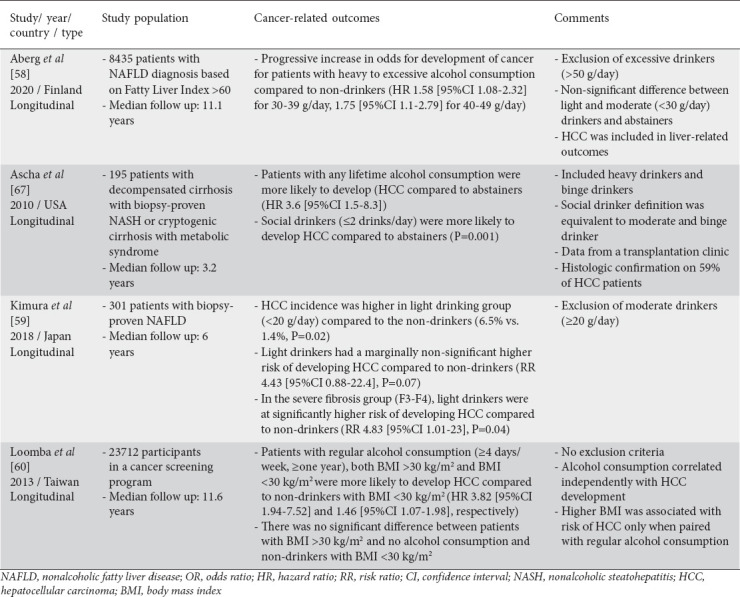

Does alcohol consumption increase the incidence of cancer in patients with NAFLD?

In the study mentioned above by Alberg et al, the association between alcohol intake and cancer was also evaluated [58]. Patients with high alcohol consumption (>30 g/day) were more likely to be diagnosed with any malignancy, whereas those with low or moderate alcohol consumption (<30 g/day) showed no increased risk for malignancies. Others assessed whether alcohol affects the risk of HCC in patients with NAFLD. Ascha et al evaluated the risk of HCC in 195 patients with NASH-related cirrhosis [59]. During a median follow up of 3.2 years, any alcohol use and even social alcohol intake were independently associated with an increased risk of HCC compared with non-drinkers. These results were reinforced by a study by Kimura et al, which evaluated the occurrence of HCC in 301 patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD [60]. During a follow up of 6 years, more patients who reported mild alcohol consumption (<20 g/day) developed HCC than patients abstaining from alcohol (6.5% vs. 1.4%). This detrimental effect of alcohol was more pronounced in patients with advanced fibrosis; in this group, mild alcohol use was independently associated with the development of HCC (risk ratio 4.83, 95%CI 1.01-23). Loomba et al evaluated the synergistic effects of alcohol and obesity on the incidence of HCC on 23,712 participants and reported similar results [61]. After a median follow up of 11.6 years, patients who consumed alcohol regularly and had BMI >30 kg/m2 had a higher incidence of HCC (HR 3.82, 95%CI 1.94-7.52) compared with patients with neither of these factors (reference population), while patients who had BMI >30 kg/m2 and did not consume alcohol regularly had a similar incidence of HCC with the reference population.

While there are only a small number of studies investigating cancer incidence in patients with NAFLD in relation to alcohol consumption, all arrive at the same conclusion: alcohol consumption in patients with NAFLD is associated with higher odds of incident cancer, with the odds increasing in parallel with alcohol consumption. Nevertheless, the lower the consumption, the weaker the association, and more studies are needed to provide data regarding light or modest alcohol consumption to justify this association. Studies investigating the effect of alcohol consumption on cancer development in patients with NAFLD are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

Studies investigating the effect of alcohol consumption on the development of cancer in patients with NAFLD

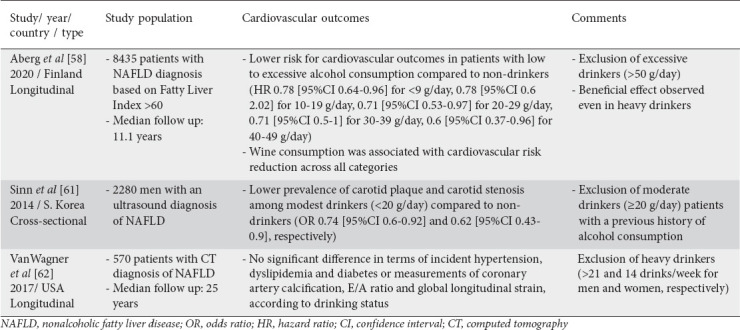

Is alcohol associated with better cardiovascular outcomes in patients with NAFLD?

Given the association of NAFLD with increased cardiovascular risk, a number of studies evaluated the effects of alcohol intake on cardiovascular morbidity. In the above-mentioned study by Aberg et al, patients with NAFLD who were consuming alcohol <50 g/day had a lower risk for cardiovascular disease compared with abstainers (HR compared with abstainers ranging from 0.6, 95%CI 0.37-0.96 in patients consuming 40-49 g/day to 0.78, 95%CI 0.64-0.95 in those consuming 0-9 g/day) [58]. This effect was even more pronounced in patients mainly consuming wine. In a study by Sinn et al in 2280 men in South Korea diagnosed with NAFLD using ultrasound, 1797 were modest drinkers (<20 g alcohol/day) and the rest did not consume any alcohol [62]. The prevalence of carotid plaques and carotid artery stenosis, surrogate markers for cardiovascular disease, was lower in the former (OR 0.74, 95%CI 0.6-0.92, and OR 0.62, 95%CI 0.43-0.9, respectively) after adjustment for age, smoking and MetS [62]. In contrast, in a recent study by VanWagner et al in 570 patients with NAFLD diagnosed by computed tomography, moderate alcohol consumption (≤14 standards drinks/week for women and ≤21 standard drinks/week for men) was not independently associated with the incidence of hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes, or with differences in measurements of coronary artery calcification, E/A ratio and global longitudinal strain after a follow up of 25 years, compared to abstainers [63].

While there is only a small number of studies regarding cardiovascular outcomes, their results imply that patients with NAFLD enjoy the same positive cardiovascular outcomes as the general population regarding moderate alcohol consumption. Notably, wine consumption seems to be the key to positive cardiovascular outcomes. Studies investigating the effect of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with NAFLD are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Studies investigating the effect of alcohol consumption on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with NAFLD

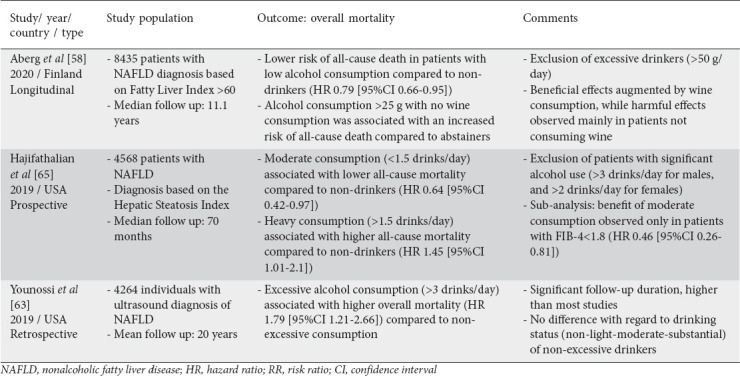

Does alcohol consumption impact all-cause mortality in patients with NAFLD?

Given that alcohol consumption appears to exert different effects on the significant causes of death in patients with NAFLD (i.e., increased risk for liver-related death and lower risk for cardiovascular mortality), a limited number of studies evaluated the overall effect of moderate alcohol consumption on all-cause mortality in this population. Aberg et al reported that alcohol consumption <10 g/day was independently associated with lower all-cause mortality compared with non-drinkers during a follow up of 11.1 years (HR 0.79, 95%CI 0.66-0.95) [58]. There was no effect of alcohol consumption between 10-50 g/day. A similar study by Younossi et al showed that only excessive alcohol consumption (>3 drinks/day) was independently associated with higher overall mortality (HR 1.79, 95%CI 1.21-2.66) compared to non-excessive consumption after 20 years of mean follow up [64]. Notably, there was no difference in terms of mortality between non-drinkers and subjects with minimal (<3 drinks/week), moderate (>3 drinks/week but <2 drinks/day) and substantial (>2 but <3 drinks/day) alcohol use. Finally, a recent study by Hajifathalian et al evaluated all-cause mortality in 4568 patients with NAFLD diagnosed with the Hepatic Steatosis Index [65] and reported that moderate consumption of alcohol (<1.5 standard drinks/day) was independently related to lower all-cause mortality (HR 0.64, 95%CI 0.42-0.97), whereas heavy consumption (>1.5 drinks/day) was independently related with higher all-cause mortality (HR 1.45, 95%CI 1.01-2.1), compared to non-drinkers during a median follow up of 70 months [66]. Interestingly the benefit of moderate consumption was limited in patients with a low probability of fibrosis (FIB-4 <1.8, HR 0.46, 95%CI 0.26-0.81) and was not observed in those with a high probability of fibrosis. Studies investigating the effect of alcohol consumption on all-cause mortality in patients with NAFLD are highlighted in Table 5.

Table 5.

Studies investigating the effect of alcohol consumption on overall mortality in patients with NAFLD

Concluding remarks

Alcohol consumption in patients with NAFLD is a relatively novel debate, considering that previous guidelines have consistently discouraged alcohol consumption in patients with (even mild) liver disease. There is currently a relatively small number of studies regarding this topic, with significant differences in terms of conclusions. Additionally, frequent underreporting of alcohol consumption combined with the difficulty of estimating lifetime consumption further complicates these studies [67]. These limitations, combined with the significant variations in terms of methods and outcomes between the studies included in this review, make it difficult to reach definite conclusions. Nevertheless, most of the studies support the same patterns regarding the effects of alcohol consumption on NAFLD: it appears that moderate alcohol intake is associated with a lower prevalence of NAFLD and reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with NAFLD, while even light alcohol intake appears to aggravate liver disease and increase the risk of HCC. Additionally, there are conflicting reports regarding the effect of alcohol on MetS and type 2 diabetes mellitus. While most studies support a positive effect of alcohol on the development of MetS and diabetes [26,31], a recent study focusing on NAFLD patients showed an increased incidence of diabetes in patients with light-to-moderate alcohol consumption (70-210 g/week) compared to abstainers. Therefore, maintaining a cautious approach, patients with NASH or significant liver fibrosis should be advised against consuming alcohol. On the other hand, taking into account recent data, only light alcohol consumption (<10 g/day) might be permitted in patients without significant hepatic fibrosis, provided that they are carefully followed-up. This recommendation is based on the fact that no study showed significant harm from light alcohol drinking, while many studies showed significant positive effects. Future studies may shed more light on this ongoing debate, possibly challenging traditional views regarding alcohol consumption in patients with liver disease.

Biography

Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki; Laiko General Hospital, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchesini G, Day CP, Dufour JF, et al. European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papatheodoridi AM, Chrysavgis L, Koutsilieris M, Chatzigeorgiou A. The role of senescence in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and progression to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2020;71:363–374. doi: 10.1002/hep.30834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328–357. doi: 10.1002/hep.29367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niikura T, Imajo K, Ozaki A, et al. Coronary artery disease is more severe in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis than fatty liver. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10:129. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10030129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Mellemkjaer L, et al. Prognosis of patients with a diagnosis of fatty liver—a registry-based cohort study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:2101–2104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tana C, Ballestri S, Ricci F, et al. Cardiovascular risk in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease:mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3104. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16173104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gellert KS, Keil AP, Zeng D, et al. Reducing the population burden of coronary heart disease by modifying adiposity:estimates from the ARIC study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e012214. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruidavets JB, Ducimetière P, Evans A, et al. Patterns of alcohol consumption and ischaemic heart disease in culturally divergent countries:The prospective epidemiological study of myocardial infarction (PRIME) BMJ. 2010;341:c6077. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellentani S, Saccoccio G, Costa G, et al. Drinking habits as cofactors of risk for alcohol induced liver damage. Gut. 1997;41:845–850. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.6.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang J, Trépo E, Nahon P, et al. PNPLA3 and TM6SF2 variants as risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma across various etiologies and severity of underlying liver diseases. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:533–544. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon HJ, Won YS, Park O, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 deficiency ameliorates alcoholic fatty liver but worsens liver inflammation and fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2014;60:146–157. doi: 10.1002/hep.27036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehm J, Taylor B, Mohapatra S, et al. Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:437–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu B, Balkwill A, Reeves G, Beral V Million Women Study Collaborators. Body mass index and risk of liver cirrhosis in middle aged UK women:prospective study. BMJ. 2010;340:c912. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bunout D, Gattás V, Iturriaga H, Pérez C, Pereda T, Ugarte G. Nutritional status of alcoholic patients:its possible relationship to alcoholic liver damage. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983;38:469–473. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/38.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iturriaga H, Bunout D, Hirsch S, Ugarte G. Overweight as a risk factor or a predictive sign of histological liver damage in alcoholics. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;47:235–238. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/47.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meier P, Seitz HK. Age, alcohol metabolism and liver disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:21–26. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f30564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy R, Catana AM, Durbin-Johnson B, Halsted CH, Medici V. Ethnic differences in presentation and severity of alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:566–574. doi: 10.1111/acer.12660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh S, Fritze G, Fang BL, et al. Inheritance of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase:genotyping in Chinese, Japanese and South Korean families reveals dominance of the mutant allele. Hum Genet. 1989;83:119–121. doi: 10.1007/BF00286702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niaura RS, Nathan PE, Frankenstein W, Shapiro AP, Brick J. Gender differences in acute psychomotor, cognitive, and pharmacokinetic response to alcohol. Addict Behav. 1987;12:345–356. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fulham MA, Mandrekar P. Sexual dimorphism in alcohol induced adipose inflammation relates to liver injury. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buch S, Stickel F, Trépo E, et al. A genome-wide association study confirms PNPLA3 and identifies TM6SF2 and MBOAT7 as risk loci for alcohol-related cirrhosis. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1443–1448. doi: 10.1038/ng.3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian C, Stokowski RP, Kershenobich D, Ballinger DG, Hinds DA. Variant in PNPLA3 is associated with alcoholic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:21–23. doi: 10.1038/ng.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines:management of alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;69:154–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furuya DT, Binsack R, Machado UF. Low ethanol consumption increases insulin sensitivity in Wistar rats. Brazilian J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:125–130. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000100017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rimm EB, Chan J, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Prospective study of cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and the risk of diabetes in men. BMJ. 1995;310:555–559. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6979.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendeloff AI. Effect of intravenous infusions of ethanol upon estimated hepatic blood flow in man. J Clin Invest. 1954;33:1298–1302. doi: 10.1172/JCI103005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, et al. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature. 2006;444:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature05354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.You M, Considine RV, Leone TC, Kelly DP, Crabb DW. Role of adiponectin in the protective action of dietary saturated fat against alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Hepatology. 2005;42:568–577. doi: 10.1002/hep.20821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakajima T, Kamijo Y, Tanaka N, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha protects against alcohol-induced liver damage. Hepatology. 2004;40:972–980. doi: 10.1002/hep.20399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alkerwi A, Boutsen M, Vaillant M, et al. Alcohol consumption and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome:a meta-analysis of observational studies. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:624–635. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ajmera VH, Terrault NA, Harrison SA. Is moderate alcohol use in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease good or bad?A critical review. Hepatology. 2017;65:2090–2099. doi: 10.1002/hep.29055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seitz HK, Mueller S, Hellerbrand C, Liangpunsakul S. Effect of chronic alcohol consumption on the development and progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2015;4:147–151. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2014.12.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeh MM, Brunt EM. Gastroenterology. Vol. 147. W.B. Saunders; 2014. Pathological features of fatty liver disease; pp. 754–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi PH, Harrison SA, Torgerson S, Perez TA, Nochajski T, Russell M. Cognitive lifetime drinking history in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:some cases may be alcohol related. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:76–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1572-0241.2003.04013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Systems biology eucidates common pathogenic mechanisms between nonalcoholic and alcoholic-fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu L, Baker SS, Gill C, et al. Characterization of gut microbiomes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients:a connection between endogenous alcohol and NASH. Hepatology. 2013;57:601–609. doi: 10.1002/hep.26093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long MT, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Benjamin EJ, Naimi TS. Alcohol use is associated with hepatic steatosis among persons with presumed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:1831–1841.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hashimoto Y, Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, et al. Modest alcohol consumption reduces the incidence of fatty liver in men:a population-based large-scale cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:546–552. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gunji T, Matsuhashi N, Sato H, et al. Light and moderate alcohol consumption significantly reduces the prevalence of fatty liver in the Japanese male population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2189–2195. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiramine Y, Imamura Y, Uto H, et al. Alcohol drinking patterns and the risk of fatty liver in Japanese men. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:519–528. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0336-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamada T, Fukatsu M, Suzuki S, Yoshida T, Tokudome S, Joh T. Alcohol drinking may not be a major risk factor for fatty liver in Japanese undergoing a health checkup. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:176–182. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Ohbora A, Takeda N, Fukui M, Kato T. Protective effect of alcohol consumption for fatty liver but not metabolic syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:156–167. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang Y, Ryu S, Kim Y, et al. Low levels of alcohol consumption, obesity, and development of fatty liver with and without evidence of advanced fibrosis. Hepatology. 2020;71:861–873. doi: 10.1002/hep.30867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moriya A, Iwasaki Y, Ohguchi S, et al. Alcohol consumption appears to protect against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:378–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moriya A, Iwasaki Y, Ohguchi S, et al. Roles of alcohol consumption in fatty liver:a longitudinal study. J Hepatol. 2015;62:921–927. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sogabe M, Okahisa T, Taniguchi T, et al. Light alcohol consumption plays a protective role against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Japanese men with metabolic syndrome. Liver Int. 2015;35:1707–1714. doi: 10.1111/liv.12754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sookoian S, Castaño GO, Pirola CJ. Modest alcohol consumption decreases the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease:a meta-analysis of 43 175 individuals. Gut. 2014;63:530–532. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagström H, Nasr P, Ekstedt M, et al. Low to moderate lifetime alcohol consumption is associated with less advanced stages of fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:159–165. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1239759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwon HK, Greenson JK, Conjeevaram HS. Effect of lifetime alcohol consumption on the histological severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2014;34:129–135. doi: 10.1111/liv.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dunn W, Sanyal AJ, Brunt EM, et al. Modest alcohol consumption is associated with decreased prevalence of steatohepatitis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) J Hepatol. 2012;57:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dixon JB, Bhathal PS, O'Brien PE. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:predictors of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis in the severely obese. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:91–100. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.25540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mitchell T, Jeffrey GP, de Boer B, et al. Type and pattern of alcohol consumption is associated with liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1484–1493. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sookoian S, Flichman D, Castaño GO, Pirola CJ. Mendelian randomisation suggests no beneficial effect of moderate alcohol consumption on the severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:1224–1234. doi: 10.1111/apt.13828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Holmqvist M, et al. Alcohol consumption is associated with progression of hepatic fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:366–374. doi: 10.1080/00365520802555991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ajmera V, Belt P, Wilson LA, et al. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, modest alcohol use is associated with less improvement in histologic steatosis and steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1511–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang Y, Cho YK, Kim Y, et al. Nonheavy drinking and worsening of noninvasive fibrosis markers in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:a cohort study. Hepatology. 2019;69:64–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.30170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Åberg F, Puukka P, Salomaa V, et al. Risks of light and moderate alcohol use in fatty liver disease:follow-up of population cohorts. Hepatology. 2020;71:835–848. doi: 10.1002/hep.30864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ascha MS, Hanouneh IA, Lopez R, Tamimi TA, Feldstein AF, Zein NN. The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1972–1978. doi: 10.1002/hep.23527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kimura T, Tanaka N, Fujimori N, et al. Mild drinking habit is a risk factor for hepatocarcinogenesis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1440–1450. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i13.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Loomba R, Yang HI, Su J, et al. Synergism between obesity and alcohol in increasing the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma:a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:333–342. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sinn DH, Gwak GY, Cho J, et al. Modest alcohol consumption and carotid plaques or carotid artery stenosis in men with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Atherosclerosis. 2014;234:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.VanWagner LB, Ning H, Allen NB, et al. Alcohol use and cardiovascular disease risk in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1260–1272. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Ong J, et al. Global NASH Council. Effects of alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome on mortality in patients with nonalcoholic and alcohol-related fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1625–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee JH, Kim D, Kim HJ, et al. Hepatic steatosis index:a simple screening tool reflecting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hajifathalian K, Torabi Sagvand B, McCullough AJ. Effect of alcohol consumption on survival in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease:a national prospective cohort study. Hepatology. 2019;70:511–521. doi: 10.1002/hep.30226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stockwell T, Donath S, Cooper-Stanbury M, Chikritzhs T, Catalano P, Mateo C. Under-reporting of alcohol consumption in household surveys:a comparison of quantity-frequency, graduated-frequency and recent recall. Addiction. 2004;99:1024–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]