Abstract

Background

Phlebitis, inflammation of tunica intima of venous wall, occurred in 13–56% of hospitalized patients. It is characterized by pain, erythema, swelling, palpable venous cord, and pussy discharge at catheter site. Cannula-related blood stream infection (CRBSI) is recognized complication of phlebitis. Adverse outcomes of phlebitis embrace patient discomfort, longer hospital stay and higher health care cost. This study aimed to determine the incidence and associated factors of peripheral vein phlebitis among hospitalized patients.

Methods

A hospital-based prospective, observational study was conducted between April 1 and August 31, 2020 at University of Gondar hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. A consecutive sampling method was used to recruit 384 patients. Patients were interviewed to obtain socio-demographic data. Relevant medical history and laboratory parameters were obtained from patients’ records. Presence and severity of phlebitis was identified by Jackson’s Visual Infusion Phlebitis (VIP) Scoring System. The Data were entered into EPI Info version 4.4.1 and transported to SPSS version 20 for analysis. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify associated factors with occurrence of phlebitis. P-value < 0.05 was used to declare significant association.

Result

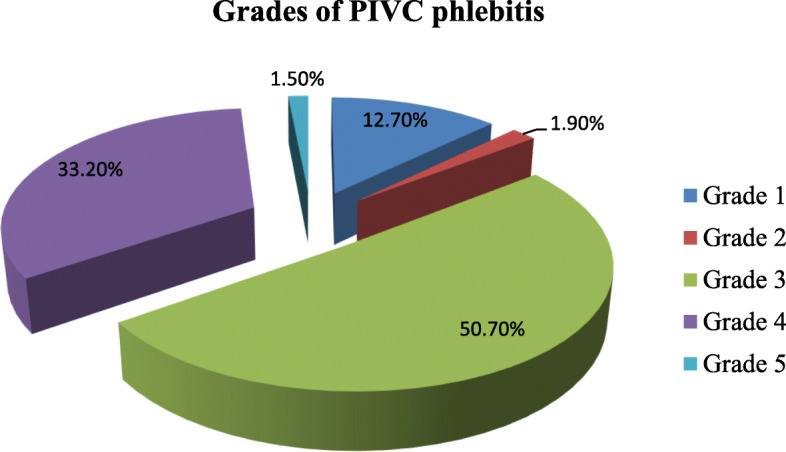

A total of 384 study subjects were included in the study. The mean age of study subjects was 46 years, with a range of 19 to 96 years. The incidence of phlebitis was 70% among study subjects. Mid-stage (grade 3) and advanced-stage (grade 4) phlebitis were noticed in 136/268 (51%) and 89/268 (33%) respectively. Odds of developing phlebitis were twofold higher in patients with catheter-in situ > 96 h (AOR = 2.261, 95% CI 1.087–4.702, P-value = 0.029) as compared to those with catheter dwell time < 72 h. Female patients were 70% (AOR = 0.293, 95% CI 0.031–0.626, P-value = 0.002) lower than male patients with risk of developing phlebitis. Patients who use infusates were 53% (AOR = 0.472, 95% CI 0.280–0.796, P-value = 0.005) less likely to develop phlebitis as compared to those who didn’t use infusates.

Conclusion

The cannula must be reviewed on daily basis, and it should be removed if it stayed later than 96 h.

Keywords: Peripheral intravenous catheters, Phlebitis, Northwest Ethiopia

Background

Peripheral intra venous catheter (PIVC) insertion is the most frequently performed procedure in hospital settings. Approximately 33–67% of hospitalized patients require at least one peripheral vein insertion. Peripheral vein catheters are required for administration of intravenous drugs, infusate solutions, blood products and parenteral feeding. It is as well necessary for access to vascular procedures [1–13]. Despite PIVC benefits, its use is not without potential complications such as phlebitis, infiltration, extravasation, occlusion and dislodgment [3, 5–10, 14–16]. Peripheral vein phlebitis occurred in 13–56% of hospitalized patients [7–10, 15, 16]. Phlebitis is clinically manifested by pain, erythema, swelling, palpable venous cord, and pussy discharge at catheter site [4–8, 10, 11, 15–17]. Cannula-related blood stream infection (CRBSI) is recognized complication of phlebitis. Presence and severity of phlebitis is evaluated by Jackson’s Visual Infusion Phlebitis Scoring System [17]. Adverse outcomes of Phlebitis embrace patient discomfort, longer hospital stay and higher health care cost [6, 9–13]. Factors contributing to occurrence of phlebitis include mechanical, chemical, biological, patient, and health practice-related factors [7–13, 15, 16]. Mechanical factors consist of cannula size, site of catheter placement, catheter dwell time and type of catheter (Teflon Vs Vialon). Teflon catheter type, large cannula size, near joint-catheter placement, and catheter dwell time > 96 h predispose to phlebitis. Type of intravenous drugs (irritant, vesicant) and solution characteristics (PH+, osmolality) are components of chemical factors. Irritant intravenous drugs and hyperosmolar infusate solutions cause vascular endothelial injury, and results in phlebitis. Biological factors embrace bacterial colonization, biofilm formation and infection. Patient-related factors take account of age, gender, nutritional status, immunosuppression and co-existing comorbidities. Those with malnutrition, immunosuppression, co-morbidities, and elderly (age > 65 years) are vulnerable to phlebitis. Implementing aseptic precautions and health professional skill on catheter securement are the frequently implicated health practice-related factors. Poor aseptic technique and improperly securing of cannula are among listed causes of phlebitis.

This study was the first of its kind in Ethiopia to determine the incidence and associated factors of peripheral vein phlebitis among adult hospitalized patients.

Methods

Study design and setting

A hospital-based prospective, observational study was conducted between April 1 and August 31, 2020 at emergency unit, medical and surgical wards of University of Gondar hospital. Both wards had a capacity of 92 beds. The hospital is located in Northwest Ethiopia, which is 750 km away from the capital, Addis Ababa. The hospital had a catchment population of 5 million people.

Study subjects and variables

Study subjects

All patients admitted to emergency unit, medical and surgical wards during the study period were considered as study population. Patients older than 18 years old, who were admitted to emergency unit, medical and surgical wards and who were on peripheral intravenous catheter, were included in the study. Patients with history of allergy to intravenous cannula, or those unable to give consent were excluded from the study.

Study variables

Dependent variables: Peripheral intravenous catheter (PIVC) phlebitis.

Independent variables: (1) Socio-demographic characteristics include age, gender, occupation, marital status, educational level, income level, residence and religion (2) Clinical characteristics include admission diagnosis, duration of hospital stay, cannula insertion site, catheter size (gauge), catheter dwell time, intravenous drugs use, infusates use, blood products use, performance level, and co-existing comorbidities.

Sample size and sampling procedure

The sample size was calculated using single population proportion formula with the assumption of 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error, and taking 50% estimated proportion of phlebitis. Consecutive sampling method was used to recruit 384 study subjects.

Data collection instrument and procedures

Data were collected through an investigator administered pre-designed questionnaire. Patients were interviewed to obtain socio-demographic data. Relevant medical history and laboratory parameters were obtained from patients’ records. Three investigators (one medical doctor, two clinical nurses) participated in the data collection process and follow-up of patients on indwelling catheter. Insertion of a catheter was performed by clinical nurses. Hygienic hand-rub with 70% alcohol was done after hand washing. Patient’s skin was disinfected using 1% iodine solution and 70% alcohol. Using clean gloves, a catheter was inserted into a peripheral vein of a patient. The catheter was fixed to the patient’s skin with protective dressing and plaster. Patients on indwelling catheter were followed daily by investigators from insertion to developing phlebitis or catheter removal. Those who developed phlebitis were graded based on Jackson’s Visual Infusion Phlebitis (VIP) Scoring System [17] and were taken care of as per the recommendations of Infusion Therapy Standard of Practice [2].

Data analysis

Data were entered into EPI Info version 4.4.1 and transported to SPSS version 20 for analysis.

Patient characteristics were reported as counts (percentages) for categorical variables, and mean with standard deviation for continuous variables. Bi-variable and multi-variable logistic regression models were constructed to identify independently associated factors with occurrence of phlebitis. Those variables with a P-value < 0.25 in the bi-variable analysis were exported to multi-variable analysis to control the possible effect of confounders. Crude odds ratio (COR) and adjusted odds ratio (AOR) were reported. P-value < 0.05 was used to declare significant association.

Ethical considerations

The research protocol complied with Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by local ethics committee (06/09/2012; IRB No. 09/26/629/12). Study subjects were recruited only after informed written consent was obtained. All data obtained were treated confidentially.

Definition of terms

Phlebitis

Occurrence of at least one inflammatory sign or symptom related to the catheter insertion, comprising persistent pain (duration longer than 2 h after end of infusion) and/or erythema and/or swelling (induration) and/or palpable cord and/or pussy discharge at intravenous site and/or pyrexia [17].

Grading of phlebitis

Grade 1 phlebitis: one of the following is evident: Pain near IV site or erythema near IV site; Grade 2 phlebitis (early stage of phlebitis): Two of the following are evident: Pain at IV site, erythema or swelling; Grade 3 phlebitis (mid stage of phlebitis): All of the following signs are evident: Pain along path of cannula, erythema and induration; Grade 4 phlebitis (advanced stage of phlebitis or early stage of thrombophlebitis): All of the following signs are evident and extensive: Pain along path of cannula, erythema, induration and palpable venous cord; Grade 5 phlebitis (Advanced stage of thrombophlebitis): All of the following signs are evident and extensive: Pain along path of cannula, erythema, induration, palpable venous cord, and visible pussy discharge at IV site or pyrexia [17].

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 384 participants were included in the study. The mean age of study subjects was 46 years, with a range of 19 to 96 years. More than half (52%) of them were males and were rural dwellers (53%). Majority (89%) of respondents were Christian by religion. Fewer than half (43%) of study subjects attended formal education (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of admitted patients with PIVC phlebitis at University of Gondar hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, April 1, 2020 to August 31, 2020

| Variables | Frequency (No.) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 15–40 | 169 | 44.0 |

| 40–60 | 125 | 32.6 |

| > 60 | 90 | 23.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 199 | 51.8 |

| Female | 185 | 48.2 |

| Religion | ||

| Christian | 343 | 89.3 |

| Muslim | 41 | 10.7 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 179 | 46.6 |

| Rural | 205 | 53.4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 69 | 18.0 |

| Married | 247 | 64.3 |

| Divorced | 32 | 8.3 |

| Widowed | 36 | 9.4 |

| Educational level | ||

| Unable to read and write | 167 | 43.5 |

| Able to read and write | 51 | 13.3 |

| Alimentary school | 67 | 17.4 |

| Secondary school | 49 | 12.8 |

| College and above | 50 | 13.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Farmer | 136 | 35.4 |

| Government employee | 52 | 13.5 |

| Merchant | 33 | 8.6 |

| Housewife | 104 | 27.1 |

| Daily laborer | 21 | 5.5 |

| Student | 25 | 6.5 |

| Others | 13 | 3.4 |

| Income level (birr) | ||

| < 1500 | 166 | 43.2 |

| 1500–2500 | 119 | 31.0 |

| 2500–3500 | 35 | 9.1 |

| > 3500 | 64 | 16.7 |

NB Others * jobless, PIVC peripheral intravenous catheter

Clinical characteristics of study participants

Two-thirds (63%) of the patients were semi-ambulatory. Majority of patients were hospitalized with lung (25%), heart (18%) and CNS (17%) diseases. Two-third (63%) of patients presumed to have bacterial infections. Fewer than 10% of patients each were diagnosed to have diabetes, CKD, HIV/AIDS, and malignancy as co-morbidities. Indications for PIVC insertion were administration of intravenous drugs (73%), infusates (65%), and blood products (14%). Half (53%) of the catheters were inserted in emergency situations. Forearm was used as catheter placement in half (52%) of patients. 20 G sized cannula was used in most (81%) patients. Two-third (66%) of patients had PIVC in-situ for 96 h or less (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of admitted patients with PIVC phlebitis at University of Gondar hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, April 1, 2020 to August 31, 2020

| Variables | Frequency (No.) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Admission diagnosis | ||

| Lung disease | 97 | 25.3 |

| Heart disease | 68 | 17.7 |

| CNS disease | 65 | 16.9 |

| Chronic liver disease | 21 | 5.5 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 16 | 4.1 |

| Hematological disorders | 18 | 4.7 |

| Fracture | 13 | 3.4 |

| Others | 86 | 22.4 |

| Performance level on admission | ||

| Ambulatory | 68 | 17.7 |

| Semi-ambulatory | 241 | 62.8 |

| Bedridden | 75 | 19.5 |

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | ||

| < 3 | 26 | 6.8 |

| 3–7 | 120 | 31.2 |

| 7–14 | 161 | 41.9 |

| > 14 | 77 | 20.1 |

| Procedure place | ||

| Emergency unit | 203 | 52.9 |

| Wards | 181 | 47.1 |

| Catheter dwell time (days) | ||

| < 3 | 171 | 31.3 |

| 3–4 | 83 | 21.7 |

| > 4 | 130 | 33.9 |

| Cannula insertion site | ||

| Dorsum of hand | 148 | 38.5 |

| Forearm | 201 | 52.3 |

| Antecubital fossa | 35 | 9.2 |

| Catheter size (gauge) | ||

| 18 | 61 | 15.9 |

| 20 | 311 | 81.0 |

| 22 | 8 | 2.1 |

| 24 | 4 | 1.0 |

| IV drugs use | ||

| Yes | 282 | 73.4 |

| No | 102 | 26.6 |

| Infusates use | ||

| Yes | 251 | 65.4 |

| No | 133 | 34.6 |

| Blood products use | ||

| Yes | 52 | 13.5 |

| No | 332 | 86.2 |

NB Others * Osteomyelitis, Bowel obstruction, PIVC peripheral intravenous catheter, IV intravenous

Table 3.

Co-morbidities among admitted patients with PIVC phlebitis at University of Gondar hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, April 1, 2020 to August 31, 2020

| Variables | Frequency (No.) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | ||

| Yes | 38 | 9.9 |

| No | 346 | 90.1 |

| Hypertension | ||

| Yes | 89 | 23.2 |

| No | 295 | 76.8 |

| HIV/AIDS | ||

| Yes | 24 | 6.3 |

| No | 159 | 41.4 |

| Unknown | 201 | 52.3 |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||

| Yes | 30 | 7.8 |

| No | 354 | 92.2 |

| Malignancy | ||

| Yes | 30 | 7.8 |

| No | 354 | 92.2 |

| Concomitant bacterial infections | ||

| Yes | 243 | 63.3 |

| No | 141 | 36.7 |

NB AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, HIV human immuno deficiency virus, PIVC peripheral intravenous catheter

Incidence and grades of phlebitis

The incidence of phlebitis was 70% (268/384) among study subjects. Among those who developed phlebitis, mid-stage (grade 3) and advanced-stage (grade 4) phlebitis were noticed in 136/268 (51%) and 89/268 (33%) respectively. Advanced stage thrombophlebitis (grade 5) occurred in 4/268 (1.5%) of phlebitis cases (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Grades of peripheral intravenous catheter (PIVC) phlebitis

Factors associated with occurrence of phlebitis

Age, gender, residence, religion, educational level, admission diagnosis, duration of hospital stay, catheter dwell time, intravenous drugs use, infusates use, and co-existing comorbidities such as HIV/AIDS and hypertension were identified as predictors of phlebitis on bi-variable analysis. When variables in bi-variable analysis with P-value < 0.25 were regressed in multi-variable analysis; only gender, catheter dwell time and infusates use were independently associated with occurrence of phlebitis. Odds of developing phlebitis were twofold higher in patients with catheter-in situ > 96 h (AOR = 2.261, 95% CI 1.087–4.702, P-value = 0.029) as compared to those with catheter dwell time < 72 h. Female patients were 70% (AOR = 0.293, 95% CI 0.137–0.626, P-value = 0.002) lower than male patients with risk of developing phlebitis. Patients who used infusates were 53% (AOR = 0.472, 95% CI 0.280–0.796, P-value = 0.005) less likely to develop phlebitis as compared to those who didn’t use infusates (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bi-variable and multi-variable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with PIVC phlebitis among admitted patients at University of Gondar hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, April 1, 2020 to August 31, 2020

| Variables | Phlebitis | COR (CI) | P-value | AOR (CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18–40 | 42 | 127 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 40–60 | 43 | 82 | 1.59 (0.91–2.77) | 0.104 | 1.19 (0.55–2.58) | 0.650 |

| > 60 | 31 | 59 | 1.02 (0.57–1.77) | 0.995 | 0.89 (0.45–1.75) | 0.730 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 128 | 71 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 140 | 454 | 0.58 (0.37–0.90) | 0.016 | 0.29 (0.13–0.63) | 0.002 |

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 119 | 60 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rural | 149 | 56 | 0.75 (0.48–1.15) | 0.187 | 0.65 (0.33–1.28) | 0.209 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Christian | 246 | 97 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Muslim | 23 | 18 | 2.07 (1.06–4.02) | 0.033 | 1.86 (0.71–4.91) | 0.210 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Unable to read and write | 126 | 41 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Able to read and write | 28 | 23 | 1.09 (0.54–2.20) | 0.817 | 1.53 (0.47–5.02) | 0.483 |

| Elementary school | 44 | 23 | 0.47 (0.21–1.08) | 0.077 | 0.77 (0.23–2.62) | 0.680 |

| Secondary school | 37 | 12 | 0.74 (0.34–1.65) | 0.467 | 1.04 (0.33–3.31) | 0.942 |

| College and above | 36 | 14 | 1.19 (0.49–2.94) | 0.692 | 1.86 (0.59–5.75) | 0.284 |

| Admission diagnosis | ||||||

| Lung disease | 69 | 28 | 1 | |||

| Heart disease | 42 | 26 | 0.90 (0.47–1.72) | 0.749 | 1.3 (0.6–2.81) | 0.511 |

| CNS disease | 47 | 18 | 0.59 (0.3–1.17) | 0.130 | 0.75 (0.33–1.70) | 0.488 |

| Liver disease | 17 | 4 | 0.95 (0.46–1.97) | 0.897 | 1.32 (0.56–3.09) | 0.522 |

| Renal disease | 8 | 8 | 1.55 (0.47–5.10) | 0.469 | 1.74 (0.48–6.34) | 0.404 |

| Hematological diseases | 12 | 6 | 1.22 (0.31–4.82) | 0.78 | 1.19 (0.26–5.46) | 0.826 |

| Fracture | 10 | 3 | 0.37 (0.12–1.09) | 0.07 | 0.45 (0.12–1.64) | 0.225 |

| Others | 63 | 23 | 0.57 (0.25–2.17) | 0.572 | 1.3 (0.37–4.59) | 0.688 |

| Co-morbidities | ||||||

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 26 | 12 | 1.07 (0.52–2.21) | 0.85 | ||

| No | 242 | 104 | 1 | |||

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 57 | 32 | 0.71 (0.43–1.17) | 0.179 | 1.08 (0.57–2.05) | 0.804 |

| No | 211 | 84 | 1 | 1 | ||

| HIV/AIDS | ||||||

| Yes | 12 | 12 | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 115 | 44 | 0.43 (0.18–1.00) | 0.050 | 0.56 (0.20–1.58) | 0.275 |

| Unknown | 141 | 60 | 1.11 (0.70–1.76) | 0.651 | 1.22 (0.71–2.11) | 0.488 |

| CKD | ||||||

| Yes | 20 | 10 | 1.17 (0.53–2.58) | 0.69 | ||

| No | 250 | 104 | 1 | |||

| Malignancy | ||||||

| Yes | 22 | 8 | 1.07 (0.50–2.54) | 0.64 | ||

| No | 248 | 106 | 1 | |||

| Concomitant bacterial infections | ||||||

| Yes | 168 | 75 | 1.09 (0.69–1.72) | 0.71 | ||

| No | 100 | 41 | 1 | |||

| Duration of hospital stay | ||||||

| < 3 days | 19 | 7 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 3–7 days | 89 | 31 | 1.47 (0.55–3.93) | 0.447 | 1.75 (0.56–5.48) | 0.338 |

| 7–14 days | 110 | 51 | 1.55 (0.83–2.89) | 0.167 | 1.73 (0.85–3.53) | 0.131 |

| > 14 days | 50 | 27 | 1.17 (0.66–2.07) | 0.603 | 1.21 (0.63–2.32) | 0.563 |

| Place of procedure | ||||||

| Emergency unit | 146 | 57 | 1 | |||

| Wards | 122 | 59 | 0.60 (0.07–5.70) | 0.65 | ||

| Catheter dwell time | ||||||

| < 3 days | 119 | 52 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 3–4 days | 66 | 17 | 1.3 (0.8–2.10) | 0.294 | 1.21 (0.68–2.15) | 0.511 |

| > 4 days | 83 | 47 | 2.2 (1.16–4.18) | 0.016 | 2.26 (1.09–4.70) | 0.029 |

| Cannula insertion site | ||||||

| Dorsum of hand | 95 | 53 | 0.85 (0.61–1.24) | 0.422 | ||

| Forearm | 144 | 57 | 0.91 (0.55–2.20) | 0.652 | ||

| Antecubital fossa | 29 | 6 | 1 | |||

| Cannula size (gauge) | ||||||

| 18 | 4120 | 1 | ||||

| 20 | 218 | 93 | 1.00 (0.63–1.98) | 1.000 | ||

| 22 | 6 | 2 | 0.78 (0.16–3.94) | 0.761 | ||

| 24 | 3 | 1 | 0.68 (0.13–3.69) | 0.660 | ||

| Intravenous drugs use | ||||||

| Yes | 202 | 80 | 0.73 (0.45–1.18) | 0.193 | 0.88 (0.49–1.59) | 0.682 |

| No | 66 | 36 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Intravenous infusates use | ||||||

| Yes | 189 | 62 | 0.48 (0.31–0.75) | 0.001 | 0.47 (0.28–0.79) | 0.005 |

| No | 79 | 54 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Blood products use | ||||||

| Yes | 37 | 15 | 0.93 (0.49–1.77) | 0.82 | ||

| No | 231 | 101 | 1 | |||

NB AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, AOR adjusted odds ratio, COR crude odds ratio, CI confidence interval, CKD chronic kidney disease, HIV human immune deficiency virus, PIVC peripheral intravenous catheter

Place of procedure done, catheter site placement, catheter size (gauge), use of blood products, concomitant bacterial infections, and co-existing comorbidities such as diabetes, CKD and malignancy were not found to be significantly associated with occurrence of phlebitis in bi-variable analysis (P-value > 0.25).

Discussion

The incidence of phlebitis was 70% with use of peripheral intra venous catheters. It was higher than phlebitis rate reported in other studies, which ranged from 13–56% [4–6, 9–13, 15, 16]. The incidence of phlebitis was much higher than acceptable phlebitis rate recommended by Infusion Nurses Society (INS), which should be 5% or less [2]. High grade phlebitis (grade 3 and 4) accounted the majority (84%) based on Jackson’s Visual Infusion Phlebitis Scoring System, which required treatment and cannula re-site. Most indwelling catheters were detected after developing advanced stage of phlebitis, which might refer to ineffective preventive measures and poor catheter management. Phlebitis significantly occurred among those with catheter dwell time > 96 h as compared to catheter-in situ < 72 h (AOR = 2.261, 95% CI 1.087–4.702, P-value = 0.029). This finding was consistent with other studies [4, 6, 8–10, 13, 15]. Prolonged catheter dwell time predisposes for continued trauma by the catheter itself, longer contact to irritant drugs and infusates, and higher chance of exposure to bacterial colonization and infections. CDC guideline (2011) recommended routine replacement of PIVC no later than 96 h. There was lower rate of phlebitis among patients who used infusates (AOR = 0.472, 95% CI 0.280–0.796, P-value = 0.005) as compared to those who didn’t use infusates. This finding could be explained by frequent use of non-risky, isotonic solutions as infusates. Isotonic infusate has equal osmolality to that of blood, so then it might reduce phlebitis rate [8–10, 15]. Lower rate of phlebitis occurred among females (AOR = 0.293, 95% CI 0.031–0.626, P-value = 0.002). It was incongruent with reports from other studies, in which females outnumbered males in incidence of phlebitis [4, 7, 12, 16]. There was no sound explanation for gender-based differences regarding incidence of phlebitis.

Limitation

Selection bias couldn’t be avoided as consecutive sampling method was used to recruit study subjects.

Conclusion

The incidence of phlebitis was considerably high. High grade phlebitis (grade 3 and 4) occurred in the majority (84%) of patients with phlebitis. Catheter dwell time > 96 h was found to be a risk factor for increased incidence of phlebitis.

Recommendation

The cannula must be reviewed on daily basis, and it should be removed if it stayed later than 96 h. Phlebitis protective measures and catheter management strategy should be improved at the study site.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to thank the study participants and their health personnel.

Authors’ contributions

ML contributed to the conception, design, data collection, analysis, writing, and review of the manuscript. AT contributed to the conception, design, analysis, writing and review of the manuscript. TT, TY and MS contributed to conception, design, analysis and review of the manuscript. All authors approved its submission for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding for research was obtained from ‘Research and Publication Office’ of College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar. The funding body had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and analyzed are included in this research article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar. Formal letter of permission was obtained from University of Gondar hospital administrative body. Study subjects were recruited only after informed written consent was obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mulugeta Lulie, Email: mulelulie@gmail.com.

Abilo Tadesse, Email: abilotad@gmail.com.

Tewodros Tsegaye, Email: teddyts2000@yahoo.com.

Tesfaye Yesuf, Email: yesuftesfaye@yahoo.com.

Mezgebu Silamsaw, Email: msilamsaw@gmail.com.

References

- 1.O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, Heard SO, et al. Summary of recommendations: guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Inf Dis. 2011;52(9):1087–1099. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Infusion therapy standard of practice Official publication of the infusion nurses society. J Inf Nurs. 2016;39:1S. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helm RE, Klausner JD, Klemperer JA, Flint LM, Huang E. Accepted but unacceptable peripheral IV catheter failure. J Infus Nursing. 2015;38:189–203. doi: 10.1097/NAN.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, LV L. The incidence and risk of infusion phlebitis with peripheral intravenous catheters: a meta-analysis. J Vasc Access. 2020;21(3):342–349. doi: 10.1177/1129729819877323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miliani K, Taravella R, Thillard D, Chauvin V, Martin E, Edouard S, et al. Peripheral venous catheter-related adverse events: evaluation from a multi-centre epidemiological study in France (the CATHEVAL project) PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0168637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cicolini G, Manzoli L, Simonetti V, Flacco ME, Comparacini D, Capasso L, et al. Phlebitis risk varies by peripheral venous catheter site and increases after 96 hours: a large multi-centre prospective study. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(11):2539–2549. doi: 10.1111/jan.12403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roca GM, Bertolo CB, Lopez PT, Samaranch GG, Ramirez MCA, Baqueras JC, et al. Assessing the influence of risk factors on rates and dynamics of peripheral vein phlebitis: an observational cohort study. Med Clin. 2012;139(5):185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simin D, Milutinovic D, Turkulov V, Brkic S. Incidence, severity and risk factors of peripheral intravenous cannula-induced complications: an observational prospective study. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:1585–1599. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S, Kim K, Kim JS. A model of phlebitis associated with peripheral intravenous catheters in orthopedic inpatients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3412–3423. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16183412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan F, Wu H, Nie L, Li W, Li L. Risk factors for phlebitis in patients with peripheral intravenous catheters. Global J Health Sci. 2020;12(1):41–45. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v12n1p41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Gupta A, Handa P, Aggarwal N, Gupta S, Kalyani VC, et al. Peripheral venous cannulation associated thrombophlebitis and its management. Eur J Med Health Sci. 2020;2(3):292–295. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandal A, Raghu K. Study on incidence of phlebitis following the use of peripheral intravenous catheter. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:2827–2831. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_559_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osei-Tutu E, Tuoyire DA, Debrah S, Ayetey H. Peripheral intravenous cannulation and phlebitis risk at Cape Coast teaching hospital. Post Grad Med J. 2015;4(1):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webster J, Osborne S, Rickard CM, New K. Clinically-indicated replacement versus routine replacement of peripheral venous catheters. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD007798. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007798.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atay S, Sen S, Cukurlu D. Phlebitis-related peripheral venous catheterization and the associated risk factors. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018;21:827–831. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_337_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abolfotouh MA, Salam M, Beni-Mustafa A, White D, Balkhy HH. Prospective study of incidence and predictors of peripheral intravenous catheter-induced complications. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;10:993–1001. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S74685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson A. An update on VIP score monitoring of peripheral IV sites with Andrew Jackson. https://pedagogyeducation.com/Main-Campus/News-Blogs/Campus-News/News.aspx?news=681.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analyzed are included in this research article.