ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to evaluate the antibacterial activity of caffeic acid (CA), which is a natural polyphenol, combined with UV-A light against the representative foodborne bacteria Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and Listeria monocytogenes. Data regarding the inactivation of these bacteria and its dependence on CA concentration, light wavelength, and light dose were obtained. E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella Typhimurium were reduced to the detection limit when treated with 3 mM CA and UV-A for 3 J/cm2 and 4 J/cm2, respectively, and 5 J/cm2 treatment induced 3.10 log reduction in L. monocytogenes. To investigate the mechanism for inactivation of Salmonella Typhimurium and L. monocytogenes, measurement of polyphenol uptake, membrane damage assessment, enzymatic activity assay, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were conducted. It was revealed that CA was significantly (P < 0.05) absorbed by bacterial cells, and UV-A light allowed a higher uptake of CA for both pathogens. Additionally, CA plus UV-A treatment induced significant (P < 0.05) cell membrane damage. In the enzymatic activity assay, the activities of both pathogens were reduced by CA, and a greater reduction occurred by use of CA plus UV-A. Moreover, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images indicated that CA plus UV-A treatment notably destroyed the intercellular structure. In addition, antibacterial activity was also observed in commercial apple juice, which showed results similar to those obtained from phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resulting in a significant (P < 0.05) reduction for all three pathogens without any changes in color parameters (L*, a*, and b*), total phenolic compounds, and DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) free radical scavenging activity.

IMPORTANCE Photodynamic inactivation (PDI), which involves photoactivation of a photosensitizer (PS), is an emerging field of study, as it effectively reduces various kinds of microorganisms. Although there are several PSs that have been used for PDI, there is a need to find naturally occurring PSs for safer application in the food industry. Caffeic acid, a natural polyphenol found in most fruits and vegetables, has recently been studied for its potential to act as a novel photosensitizer. However, no studies have been conducted regarding its antibacterial activity depending on treatment conditions and its antibacterial mechanism. In this study, we closely examined the effectiveness of caffeic acid in combination with UV-A light for inactivating representative foodborne bacteria in liquid medium. Therefore, the results of this research are expected to be utilized as basic data for future application of caffeic acid in PDI, especially when controlling pathogens in liquid food processing.

KEYWORDS: caffeic acid, ultraviolet-A, foodborne bacteria, antibacterial activity, inactivation mechanism, apple juice

INTRODUCTION

Photodynamic inactivation (PDI), which involves light and a photosensitizer to inactivate microorganisms, has recently been recognized as a promising technology to ensure food safety, not only in medicine (1, 2). The principle behind PDI is based on oxidative mechanisms that basically result in reactive oxygen species (ROS) attacking various cell structures such as the cell membrane or protein, which leads to cell inactivation (3). As ROS are the main mechanism, there is so far no reported antimicrobial resistance against PDI (4), which makes it attractive for applying the technique for inactivating foodborne pathogens in food processing.

The photosensitizers (PSs) in PDI mainly consist of endogenous PS, usually porphyrins that naturally occur inside bacterial cells (5), and exogenous PS. There are a wide variety of exogenous PSs, from inorganic to organic materials. For instance, in the study of Ercan et al. (6), UV-A irradiated zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles induced 6 log reductions of Escherichia coli BL21. In addition to ZnO nanoparticles, titanium dioxide nanoparticles are another candidate for inorganic photosensitizer that has been widely applied in biomedical fields (7, 8). Since involving exogenous PSs for PDI enhances its effect, there have been numerous approaches to search for better and safer exogenous PSs that occur naturally. In the recent few years, phenolic compounds have emerged as promising candidates of naturally occurring PSs, as they were proven to effectively generate ROS upon light irradiation. For example, curcumin, which is a naturally occurring phenolic compound found in Curcuma longa, has been applied to inactivate E. coli O157:H7 and Listeria innocua in combination with UV-A light and resulted in a >5 log reduction even with low concentrations (1 to 10 mg liter−1) of curcumin (9). In addition, benzoic acid, which is a generally recognized as safe (GRAS) compound, also induced a >5 log reduction in E. coli O157:H7 combined with UV-A light at a concentration of 15 mM (10).

Caffeic acid is a phenolic compound that is naturally abundant in fruits and vegetables. Although polyphenols, including caffeic acid, are usually known as antioxidants and have antimicrobial activities against pathogens (3, 11), it has recently been discovered that they can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon photoirradiation by oxidation and show bactericidal activities (12). For example, exposure to blue light (400 nm) at 4 mM gallic acid resulted in a >5 log reduction in Staphylococcus aureus (13). Similarly, caffeic acid (5 mM) with blue light (400 nm) was able to inactivate E. coli O157:H7 and L. innocua by 4 and 1 log CFU/ml, respectively (14). In the study of Nakamura et al. (15), a more than 5 log reduction in Streptococcus mutans biofilms occurred when they were treated with the combination of caffeic acid and light. Therefore, considering the natural occurrence of caffeic acid and its ability to produce ROS when subjected to light while also acting as an antioxidant, there is a need for a study on caffeic acid as a novel photosensitizer.

One of the most important factors of photodynamic treatment is applying a light source of an appropriate wavelength that coincides with the absorption wavelength of the photosensitizer. However, although the absorption maximum of caffeic acid is situated near 360 nm (16), there is a lack of studies on the combination of caffeic acid and UV-A light for inactivating foodborne pathogens. Hence, the aim of the present study was to closely examine the antibacterial activity of photoirradiated caffeic acid using UV-A light-emitting diodes (LEDs) at various concentrations, light wavelengths, and light doses to establish adequate treatment conditions. Furthermore, to investigate the bactericidal mechanism, polyphenol uptake, membrane damage, and enzymatic activity were measured and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was conducted for visualization. To evaluate the possibility of its future application in the food industry, the antibacterial activity in apple juice was studied and its quality factors such as color, total phenols, and DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) free radical scavenging activity were measured.

RESULTS

Inactivation of foodborne pathogens in PBS under various conditions.

The log reduction values or surviving populations of foodborne pathogens in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at various concentrations (Fig. 1), light wavelengths (Fig. 2), and light doses (Fig. 3) are shown. As shown in Fig. 1, to examine an appropriate concentration for the following treatments, caffeic acid (CA) concentrations up to 4.50 mM were tested. Caffeic acid (single treatment resulted in a <1 log reduction at every concentration for all three pathogens except for Salmonella Typhimurium, which showed a 1.91 log reduction only at the highest concentration of 4.50 mM. However, when treated with 3.39 mM and 4.50 mM CA combined with UV-A, E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella Typhimurium were reduced to under the detection limit (1 log CFU/ml), and for L. monocytogenes, 4.88 and 5.14 log reduction values were obtained, respectively. To establish a specific concentration for further experiments, the concentration that minimizes the sole effect of CA and maximizes the synergistic effect of CA plus UV-A was chosen, which was 3 mM.

FIG 1.

Reduction of bacterial populations of E. coli O157:H7 (A), Salmonella Typhimurium (B), and L. monocytogenes (C) subjected to CA, UV-A only, and CA plus UV-A at various concentrations of CA. The light dose of UV-A was fixed at 10 J/cm2. The error bars indicate standard deviations. Different uppercase letters for cells subjected to same treatment indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Different lowercase letters for the same caffeic acid concentration indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

FIG 2.

Reduction of bacterial populations of E. coli O157:H7 (A), Salmonella Typhimurium (B), and L. monocytogenes (C) subjected to LED and CA plus LED with LEDs of 365 nm and 408 nm. The light dose and CA concentration were fixed at 10 J/cm2 and 3 mM, respectively. The error bars indicate standard deviations. Different uppercase letters for cells subjected to same treatment indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Different lowercase letters for same wavelength indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

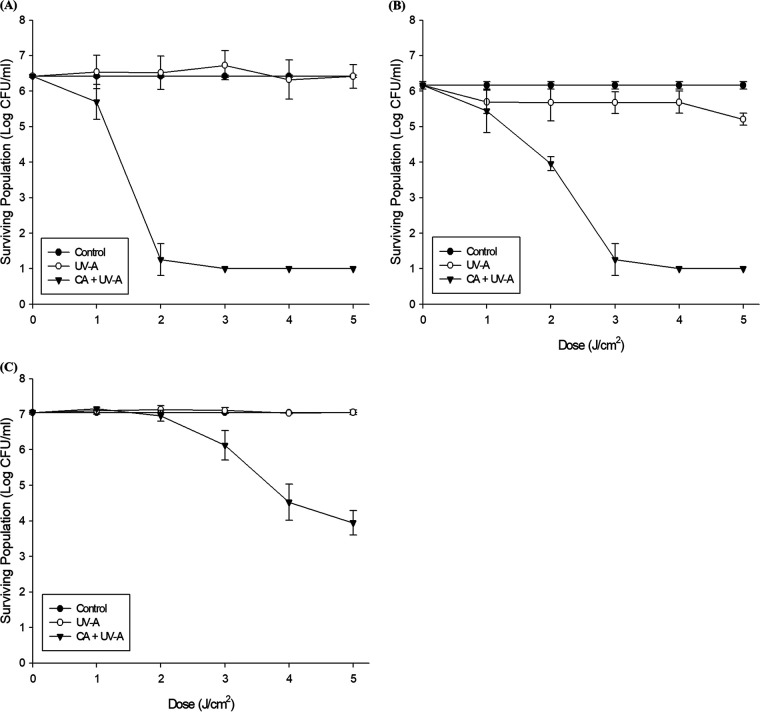

FIG 3.

Surviving populations of E. coli O157:H7 (A), Salmonella Typhimurium (B), and L. monocytogenes (C) subjected to UV-A and CA plus UV-A. UV-A light dose was varied from 1 to 5 J/cm2 and CA concentration was fixed at 3 mM. The error bars indicate standard deviations. The limit of detection was 1 log CFU/ml.

When the pathogens were subjected to 3 mM CA and LEDs with light wavelengths of 365 nm (UV-A) and 408 nm (blue light), CA plus blue LEDs did not show a significant reduction in wavelength compared to that of blue LEDs only (Fig. 2). However, CA plus UV-A brought a synergistic effect of 5.28, 3.42, and 5.67 log reduction for E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, and L. monocytogenes, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, 3 mM CA plus UV-A reduced E. coli O157:H7 (Fig. 3A) and Salmonella Typhimurium (Fig. 3B) to the detection limit at the light doses of 3 J/cm2 and 4 J/cm2, and 5 J/cm2 resulted in 3.10 log reduction for L. monocytogenes (Fig. 3C).

Polyphenol uptake measurement.

The values of polyphenol uptake, as shown in Table 1, were calculated by dividing each absorbance signal by the control. For both pathogens, UV-A-treated group showed no significant difference (P > 0.05) in its value, and groups that were treated with CA only and CA plus UV-A both showed significantly (P < 0.05) higher values than that of the control. Additionally, CA plus UV-A showed even higher uptake values than those of the CA-treated group in both pathogens.

TABLE 1.

Polyphenol uptake values of Salmonella Typhimurium and L. monocytogenes obtained from four groups (control, UV-A, CA, and CA plus UV-A)

| Polyphenol uptake valuesa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strain | Control | UV-A | CA | CA + UV-A |

| Salmonella Typhimurium | 1.00 ± 0.00 A | 1.08 ± 0.02 A | 49.10 ± 16.85 B | 94.79 ± 23.71 C |

| L. monocytogenes | 1.00 ± 0.00 A | 0.94 ± 0.08 A | 90.43 ± 39.88 B | 131.75 ± 31.78 C |

The values were calculated by dividing the obtained absorbance with control value. Data were expressed as means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments. Values in the same row with the same uppercase letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Membrane damage assessment.

Fig. 4 shows the membrane damage values obtained by measuring propidium iodide (PI) uptake values after each treatment. Each value was calculated by dividing each fluorescence by the control. For both pathogens, UV-A and CA single-treated groups did not show any significant increase in their PI uptake values (P > 0.05). In contrast, the values were significantly (P < 0.05) increased in the CA-plus-UV-A-treated groups.

FIG 4.

Membrane damage values obtained by measuring propidium iodide (PI) uptake values after each treatment of Salmonella Typhimurium (A) and L. monocytogenes (B). The values were calculated by dividing the obtained fluorescence (F) by the control value (F0). Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Respiratory chain dehydrogenase activity measurement.

In Fig. 5, the measured absorbances at 490 nm of each group, which are the quantitative data of iodonitrotetrazolium formazan (INF), were expressed as the percentage (%) relative to the control value. Although UV-A induced a slight decrease in INF measurement in Salmonella Typhimurium, it did not show any significant effect (P > 0.05) compared to the control in L. monocytogenes. In contrast, in all groups with CA treatment, the INF measurement (%) values were significantly (P < 0.05) reduced. Furthermore, when combined with UV-A light, CA significantly (P < 0.05) enhanced the ability of the treatment to inhibit bacterial respiratory enzymes in L. monocytogenes but showed no further effect (P > 0.05) in Salmonella Typhimurium.

FIG 5.

Respiratory chain dehydrogenase activity values obtained by INF measurement of Salmonella Typhimurium (A) and L. monocytogenes (B). The values indicate the percentage (%) relative to the control group. The error bars are standard deviations from three replicate experiments. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Transmission electron microscopy image.

As shown in Fig. 6, Salmonella Typhimurium subjected to each treatment and its control was examined using transmission electron microscopy. Although the groups that were treated with UV-A and CA (Fig. 6B and C, respectively) seemed to show a slightly wrinkled cell membrane, severe disruptions in cell morphology compared to that of the control (Fig. 6A) were not detected visually. However, CA-plus-UV-A-treated cells (Fig. 6D) exhibited fatally destroyed internal cellular materials, which are marked with arrows.

FIG 6.

TEM images of Salmonella Typhimurium with control (A), UV-A (B), CA (C), and CA plus UV-A (D) treatments.

Application in apple juice and its quality measurement.

Figure 7 presents the surviving populations of E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, and L. monocytogenes in apple juice treated with UV-A, CA, and CA plus UV-A. Although UV-A and CA treatment resulted in a slight decrease in the Salmonella Typhimurium population (Fig. 7B), the other two pathogens (Fig. 7A and C) were not significantly reduced (<1 log reduction). Additionally, in CA plus LED, light doses of 7 J/cm2 and 5 J/cm2 led to a complete reduction in E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella Typhimurium, respectively, and 9 J/cm2 resulted in a 3.94 log reduction in L. monocytogenes (Fig. 7C). To examine whether CA plus UV-A treatments generate a difference in apple juice quality, the quality values of color, DPPH free radical scavenging activity, and total phenol amount are listed in Table 2. Compared to those in the control, which was apple juice without any treatment, color values and DPPH free radical scavenging activity (%) values did not show any significant difference (P > 0.05). As caffeic acid, which is a polyphenol, was added to each sample, the total phenol amount was increased compared with that of the control. However, combining UV-A light did not have a significant (P > 0.05) effect on the values compared to treatment with CA without UV-A light, as in the 0 J/cm2-treated group.

FIG 7.

Surviving populations in apple juice of E. coli O157:H7 (A), Salmonella Typhimurium (B), and L. monocytogenes (C). All strains were subjected to 3 mM CA and UV-A light dose of 1 to 9 J/cm2. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

TABLE 2.

Quality values (color, DPPH free radical scavenging activity, and total phenol content) of apple juice

| Dose (J/cm2)a | Quality valueb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color |

DPPH free radical scavenging activity (%) | Total phenol (mg GAE/liter) | |||

| L* | a* | b* | |||

| Control | 36.17 ± 0.05 A | 0.12 ± 0.02 A | 0.39 ± 0.03 A | 76.37 ± 0.22 A | 91.97 ± 1.14 A |

| 0 | 36.16 ± 0.02 A | 0.15 ± 0.03 A | 0.34 ± 0.04 A | 76.77 ± 0.33 A | 366.17 ± 14.90 BC |

| 1 | 36.12 ± 0.05 A | 0.14 ± 0.04 A | 0.39 ± 0.03 A | 76.53 ± 0.22 A | 373.38 ± 10.65 BC |

| 3 | 36.15 ± 0.06 A | 0.12 ± 0.01 A | 0.35 ± 0.05 A | 76.45 ± 0.55 A | 353.42 ± 10.22 C |

| 5 | 36.16 ± 0.02 A | 0.11 ± 0.08 A | 0.34 ± 0.12 A | 76.30 ± 0.33 A | 388.86 ± 22.49 B |

| 7 | 36.19 ± 0.05 A | 0.10 ± 0.03 A | 0.32 ± 0.06 A | 76.61 ± 0.33 A | 380.98 ± 22.78 BC |

| 9 | 36.14 ± 0.04 A | 0.15 ± 0.05 A | 0.35 ± 0.03 A | 76.37 ± 0.22 A | 376.88 ± 30.41 BC |

Control is an untreated apple juice sample. Groups treated with CA plus UV-A are expressed with numbers that indicate treatment dose (J/cm2).

Data were expressed as means ± standard deviations. Values in the same column with the same uppercase letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The main objective of this study was to investigate the antibacterial activity of caffeic acid (CA) combined with UV-A light. To accomplish this, we needed to establish optimum treatment conditions, such as concentration, light wavelength, and light dose. Although CA is mainly soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol or dimethyl sulfoxide, distilled water was chosen as the solvent to prevent any effect on cells induced by the solvent itself. As the maximum solubility of CA in water at room temperature is 0.98 g/liter (17), CA concentrations up to 4.50 mM were examined. As stated above, 3 mM was selected for further experiments since it was in the range of the concentrations with minimum sole effect of CA and maximum synergistic effect of CA plus UV-A, which means a complete inactivation of E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella Typhimurium. In addition to concentration, another crucial factor of photodynamic treatment is applying an appropriate wavelength, which means accordance with the absorption wavelength of photosensitizer and the emission wavelength of the LED (1). Therefore, since the absorption maximum of CA is situated near 360 nm to 370 nm (16), a 365-nm LED was utilized in our study. To validate its advantage over blue LEDs, bacterial reduction values were compared over E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, and L. monocytogenes (Fig. 2). According to the results, exerting 408-nm blue light resulted in a less than 1 log CFU/ml reduction for all three pathogens. However, when 365-nm LEDs were combined with CA, a considerable reduction appeared, i.e., a more than 5 log reduction for every pathogen. Considering that previous studies of photodynamic treatment using polyphenols commonly apply blue light, this finding enlightens the potential of UV-A light to induce a more synergistic effect in inactivating foodborne pathogens than that of blue light.

In Fig. 3, although UV-A single treatment did not result in significant inactivation (<1 log reduction), E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella Typhimurium subjected to CA plus UV-A were reduced to under the detection limit even at the low dose of 3 to 4 J/cm2. Comparatively, L. monocytogenes required a higher light dose for a similar amount of inactivation. Generally, Gram-negative bacteria are reported to be more resistant to photodynamic treatment than are Gram-positive bacteria since their outer membrane acts as a permeability barrier for PS molecules (18). Therefore, additional treatments to disorganize their outer membrane are required to enhance the inactivation of Gram-negative bacteria, such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) pretreatment or conjugation of PS with polycationic molecules (19, 20). However, in this study, CA plus UV-A treatment was even more effective toward Gram-negative bacteria. Therefore, it can be inferred that CA was able to effectively penetrate the outer membrane of E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella Typhimurium unlike other photosensitizers. In addition, Gram-positive bacteria are reported to be more resistant to oxidative damage than are Gram-negative bacteria (21). As Gram-positive bacteria possess a thick peptidoglycan layer, they can block ROS molecules such as hydroxy radicals from entering the cells and consequently protect them from oxidative damage. However, Gram-negative bacteria have lipopolysaccharides in the outer membrane which are relatively susceptible to damage. Additionally, according to Nakamura et al. (12), Gram-positive bacteria were more resistant to the combination treatment of polyphenols and light, which matches the results in this study. To summarize, although CA could effectively enter both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria would have shown their resistance to oxidative damage which resulted in less reduction by CA plus UV-A treatment. The ability to penetrate the cell membrane of CA would be further stated.

As UV-A and CA single treatments did not result in a significant reduction for every pathogen, it is necessary to examine each action of UV-A, CA, and CA plus UV-A to determine which mechanism is responsible for the synergistic antibacterial effect of CA plus UV-A. It is known that the main mechanism by which UV-A inhibits microorganisms is the generation of oxidative damage to cellular DNA (22). In comparison to UV-C, which directly alters microbial DNA by producing a variety of photoproducts (23), UV-A inactivates bacteria rather indirectly by accumulating oxidative stress to cellular components such as proteins, membrane, and DNA that leads to lethal or sublethal cell damage (24–26). Therefore, it is suggested that there is a certain threshold of damage that should be exceeded to lead to complete cell death by UV-A only (27), which means that a sufficient amount of light dose is required. Since the overall maximum light dose of UV-A was only 10 J/cm2 in this study, the sole effect of UV-A might have been negligible for the cells.

Next, to examine the interaction between the cells and CA, the uptake of CA by bacterial cells was observed (Table 1). As a result, CA was noticeably detected in both Salmonella Typhimurium and L. monocytogenes even when treated alone. Although no reduction in the bacterial population occurred when treated with CA, it can be interpreted that CA itself can permeate the cell membrane and be absorbed by bacterial cells. Polyphenols are usually known to act as antimicrobial agents by interacting with the bacterial cell wall and cell membrane (28). Specifically, phenolic acids such as caffeic acid have a partial lipophilic structure and are assumed to passively diffuse into the cell membrane and further induce disruption even for Gram-negative bacteria (29). Hence, in the same context, it can be inferred from the CA uptake values that CA was able to diffuse and permeate into the cells without any additional assistance of light. As in this experiment, however, the treatment time for CA was relatively short, reaching a maximum of 10 m 40 s; it would have been insufficient for CA to exert its antimicrobial activity by itself.

Meanwhile, the uptake values of CA plus UV-A were significantly (P < 0.05) higher than those of the CA group in both pathogens. This indicates that UV-A irradiation helped CA molecules diffuse into bacterial cells even more. When treated with CA plus UV-A, the dissolved CA outside the cells would have produced reactive oxygen species (ROS) and brought damage to the cell membrane so that CA molecules could move into bacterial cells more easily than before. The results of the membrane damage assessment (Fig. 4) also coincide with this interpretation. In both pathogens, the PI uptake values only in the CA-plus-UV-A-treated groups were significantly (P < 0.05) higher than those in the control group, which indicates that damage to the cell membrane occurred when CA was assisted with UV-A. In summary, based on the fact that CA produces ROS by photooxidation upon light irradiation and is able to be strongly absorbed inside cells, it would be able to produce ROS not only outside the cells but also intracellularly, making it advantageous to destroy the inner cell structure directly. This would explain why CA-plus-UV-A-treated bacteria were able to be effectively inactivated.

To further examine the inactivation mechanism, respiratory chain dehydrogenase activity values were obtained (Fig. 5). If there is a decrease in the value of optical density at 490 nm (OD490), which measures the amount of INF production, it indicates a reduction in the respiratory dehydrogenase activity of bacteria. In both Salmonella Typhimurium and L. monocytogenes, there was a significant decrease in INF measurement in all CA-treated groups. This result is consistent with those of other previous reports, showing the ability of polyphenols to inhibit bacterial enzyme activity, including respiratory enzymes. Specifically, according to Haraguchi et al. (30), licochalcone A and C, which are natural phenols, were found to inhibit bacterial respiration chain. Additionally, Konishi et al. (31) showed that tannins have the ability to reduce NADH dehydrogenase activity in various organisms such as Paracoccus denitrificans and Bacillus subtilis. Therefore, CA would have inhibited bacterial enzymes itself in both pathogens, although it did not actually result in a significant reduction in the bacterial population, since many factors other than enzyme damage comprehensively contribute to cell death. Although both CA-treated groups whether with or without UV-A were affected, the lowest value was observed in CA plus UV-A for L. monocytogenes, which suggests the possibility of simultaneous treatment with CA and UV-A to more effectively inhibit bacterial enzymatic activity than does single treatment.

TEM images (Fig. 6) were obtained for visual analysis of the inactivation mechanism. As seen in the figure, among the four groups of control and treated groups, only the CA-plus-UV-A-treated bacteria (Fig. 6D) showed severe destruction of the inner cell structure compared to other groups with slight or no morphological differences. Considering this, together with the explanations above, it is suggested that CA plus UV-A was an effective treatment by completely destroying the inner cell structure by generating ROS from inside the cells.

Meanwhile, there have been several outbreaks in association with unpasteurized apple juice contaminated mainly by E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella spp. (32). To prevent these outbreaks, in 2001 the FDA published a regulation that requires juice processors to put preventive steps in juice production that result in an at least 5 log reduction in pathogenic bacteria (33). For apple juice pasteurization, thermal processing is traditionally the main technique. However, as thermal processes affect juice quality, nonthermal processing such as UV-C irradiation (34) has been widely studied as an alternative. Recently, there have been a few approaches to apply photodynamic treatment in the fruit juice industry. For example, in the study of Bhavya et al. (35), sono-photodynamic inactivation using curcumin as a photosensitizer was applied in orange juice. Also, in another study, erythrosine B was utilized for photodynamic inactivation of foodborne pathogens in tomato juice (36). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of studies that apply photodynamic treatment to apple juice, not to mention use polyphenols as photosensitizers. According to our results, CA plus UV-A treatment in apple juice resulted in a more than 5 log reduction in both E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella Typhimurium at doses of 7 and 5 J/cm2, respectively, which follows FDA regulation, and a 4 log reduction at 9 J/cm2 also occurred in L. monocytogenes. Furthermore, color and DPPH free radical scavenging activity were not significantly (P < 0.05) affected by CA plus UV-A treatment at any light dose. Although caffeic acid, which is a phenol, was added to apple juice, the values of total phenol content were obviously increased, and they were not affected by further light treatment, which indicates that CA plus UV-A treatment in apple juice does not deteriorate its quality. Additionally, as polyphenols are reported as effective antioxidants that are beneficial to human health (37, 38), an increase in the total phenol content of apple juice by caffeic acid treatment could possibly enhance its nutritional factor.

In conclusion, the combination treatment of caffeic acid and UV-A LEDs effectively inactivated E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, and L. monocytogenes in both PBS and commercial apple juice with no adverse effect on quality. As caffeic acid is a naturally occurring polyphenol with various health benefits, this study will provide possibilities and guidelines for the future application of caffeic acid plus UV-A treatment to food industries, including fruit juice processing by effectively reducing foodborne pathogens. Nonetheless, although previous studies have found that polyphenols generate reactive oxygen species upon light irradiation, further studies are required, as it remains unclear which ROS act as a main bactericidal factor in CA plus UV-A treatment. Additionally, studies regarding other microorganisms, such as bacterial spores, yeasts, and molds, should be conducted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Three strains of E. coli O157:H7 (ATCC 35150, ATCC 43889, and ATCC 43890), Salmonella Typhimurium (ATCC 19585, ATCC 43971, and DT104), and L. monocytogenes (ATCC 19111, ATCC 19115, and ATCC 15313), acquired from the bacterial culture collection of Seoul National University (Seoul, South Korea), were used in this study. Stock culture was prepared by preserving the strains in 0.7 ml of tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Difco, BD) mixed with 0.3 ml of sterile 50% glycerol at −80°C. To make working cultures, strains were streaked onto tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Difco, BD), incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and stored at 4°C. A single colony of each strain from TSA plate was separately inoculated into 5 ml TSB and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a shaking incubator. All TSB were combined and the cell pellets were harvested by centrifugation (4,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C). The obtained pellets were washed with sterile 0.2% peptone water (PW) (Bacto, Sparks, MD, USA) and resuspended in 9 ml of 0.2% PW, yielding bacterial population of approximately 107 to 108 CFU/ml.

Preparation of caffeic acid stock solution.

Caffeic acid (CA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) stock solution was prepared in sterile distilled water to the desired concentration, with constant stirring and heating to 80°C until completely dissolved. The concentrations used in the following treatments were determined based on CA solubility in water (17). The CA stock solution was freshly prepared on the day of each experiment. Additionally, to examine the accurate bacterial inactivation ability of CA plus UV-A in apple juice, appropriate amounts of CA were dissolved in commercial apple juice (purchased from a local market) instead of in distilled water. It was shown that this amount does not result in significant bacterial inactivation from preliminary experiments (data not shown).

Treatment setup.

A mixture of PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) and CA solution or apple juice (either with or without CA) was placed in a petri dish (60 by 15 mm2) and inoculated with the bacterial cocktail up to a volume of 5 ml for each treatment. Except for the apple juice for which the concentration was set beforehand, the volume of PBS and CA stock solution was adjusted each time to obtain the desired concentration of CA in the final state. The mixture was constantly stirred with a magnetic stir bar during the treatments, and the distance between the top of the sample and LED was fixed at 6 cm. The light dose and CA concentration used were varied based on the objectives of each experiment (see below).

For light treatments, four UV-A LEDs (365 nm) and blue LEDs (408 nm) were used. The intensity of LEDs was measured with a spectrometer (AvaSpec-ULS2048-USB2-UA-50, Avantes; Apeldoorn, Netherlands). As the distance between the LEDs and the sample was set at 6 cm as mentioned above, the irradiance values were also measured correspondingly. To ensure that a uniform irradiance to the petri dish was provided for light treatments, a petri factor was calculated by measuring the intensity for every 5 mm of the surface area. The intensity values obtained at each point were divided by the maximum value and averaged to earn the petri factor. The modified irradiance values, which were calculated by multiplying the petri factor and the maximum irradiance value, were 15.58 and 30.47 mW/cm2 for UV-A (365 nm) and blue LED (408 nm), respectively. These values were used throughout the whole experiments.

Bacterial enumeration.

After each treatment, 1 ml of each sample of either PBS or apple juice was withdrawn and 10-fold serial dilution was followed in 9 ml of sterile 0.2% buffered PW. Aliquots of 0.1 ml of samples or diluents were then spread plated onto selective medium and incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and typical colonies were counted thereafter. Sorbitol MacConkey agar (SMAC) (Difco), xylose lysine desoxycholate agar (XLD) (Oxoid), and Oxford agar base with antimicrobial supplement (OAB) (MB cell) were used to enumerate E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, and L. monocytogenes, respectively.

Analysis of inactivation mechanisms.

To investigate the inactivation mechanism of CA plus UV-A LED on pathogens, measurement of polyphenol uptake, membrane damage assessment, enzymatic activity assay, and transmission electron microscopy were conducted on Salmonella Typhimurium and L. monocytogenes. These pathogens were selected as the representatives of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, respectively. For each analysis, four groups of control, UV-A, CA, and CA plus UV-A were examined for comparative data. Light dose, or the corresponding amount of time for CA treatment, was fixed at 2.5 J/cm2 and 5 J/cm2 for Salmonella Typhimurium and L. monocytogenes each to equalize treatment conditions. The fluorescence or absorbance values were normalized by dividing the signal by OD600 of cells.

To measure the uptake of CA, a specific flavonoid dye, diphenylboric acid 2-aminoethyl ester (DPBA) (Sigma-Aldrich), was used according to a previous method (39). Briefly, as DPBA can permeate the bacterial membrane, it is able to bind to flavonoids and become fluorescent. After each treatment, 1 ml of sample was withdrawn, centrifuged at 10,000 relative centrifugal force (rcf) for 2 min, and washed with distilled water (DW) twice. For the next step, the pellet was resuspended in 450 μl of DPBA (0.2% wt/vol in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]). From the final solution, the fluorescence was measured with a spectrophotometer (Spectramax M2e; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at excitation/emission wavelength of 405/465 nm.

Bacterial membrane damage was measured by using a fluorescent dye, propidium iodide (PI; Sigma-Aldrich). When bacterial membrane is destructed, PI can bind to cellular DNA. Hence, the value of PI uptake, which can be measured by its fluorescence, can indicate the amount of membrane damage. After each treatment, 990 μl of treated cells was mixed with 10 μl PI solution to the final concentration of 2.9 μM and incubated in the dark for 10 min at 37°C. After incubation, each sample was centrifuged (10,000 × g, 10 min) and washed twice with PBS to cease the reaction by removing the excess dye. Finally, the centrifuged pellet was resuspended in PBS and its fluorescence was measured with an excitation/emission wavelength of 495/615 nm.

The enzymatic activity assay was conducted using a colorless iodonitrotetrazolium chloride (INT) (Sigma-Aldrich), which turns to a red iodonitrotetrazolium formazan (INF) by the bacterial respiratory chain dehydrogenase. This assay was based on the preceding method (40). Briefly, after each treatment, 0.9 ml of sample (either control or treated) was mixed with 0.1 ml of 0.5% INT solution and incubated in the dark at 37°C for 2 h. Next, the solution was centrifuged (10,000 rcf, 2 min) and the supernatant was discarded to obtain a cell pellet. One milliliter of acetone-ethanol (1:1 ratio) mixture was then added to the pellet and dissolved for an equivalent length of time, and 490 nm absorbance was measured.

Lastly, to visually examine the inactivation mechanism, TEM was conducted for Salmonella Typhimurium. After each treatment, 1 ml of each sample was transferred to a 1.5-ml microtube and centrifuged (10,000 rcf, 10 min). The cell pellet was then prefixed with Karnovsky’s fixative overnight at 4°C. The prefixed cells were washed with 0.05 M sodium cacodylate buffer three times for 5 min, and 1 ml of 1% osmium tetroxide diluted in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer was added for postfixation to each sample at 4°C for 2 h. After washing with distilled water for 5 min three times, the samples were immersed in 0.5% uranyl acetate overnight at 4°C for en bloc staining. The stained cells were then washed with distilled water and dehydrated using 30, 50, 70, 80, 90, and 100% ethanol gradually, three times for 10 min each. For transition, propylene oxide was added to dehydrated samples for 15 min twice and each sample was then penetrated using 1:1 and 1:2 mixtures of propylene oxide and Spurr’s resin for 1 h. By adding Spurr’s resin, the samples were polymerized and the final samples were kept at 70°C for 24 h. The polymerized samples were subjected to ultrathin slicing, placed on copper grids, stained, and observed using a 120-kV TEM (Libra 120; Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Quality measurement of apple juice.

To measure the change in apple juice quality after CA plus UV-A treatment, color, total phenols, and DPPH free radical scavenging activity of apple juice were examined. Apple juice subjected to 0 (control), 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 J/cm2 light doses of CA plus UV-A was used for the measurement. Color values (L*, a*, and b*) were measured by a Minolta colorimeter (CR400; Minolta Co., Osaka, Japan). Each of the values indicates lightness, redness, and yellowness (41).

To measure the amount of total phenols, Folin-Ciocalteu assay was conducted (42). In this procedure, 5 ml of 0.2 N Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to a 1-ml aliquot of each apple juice sample and incubated for 3 min at room temperature. Thereafter, 4 ml of 7.5% sodium carbonate (Samchun Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd., Pyeongtaek, South Korea) was mixed with the previous mixture and maintained for 2 h at room temperature. From the final sample, the absorbance at 765 nm was measured using the spectrophotometer and distilled water was used as a blank sample. For the calibration curve, a standard solution of gallic acid was applied and the results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per liter.

DPPH free radical scavenging activity measurement was conducted by using 0.2 mM DPPH solution dissolved in methanol. Two milliliters of 0.2 mM DPPH solution was mixed with 2 ml of apple juice sample and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The absorbance at 517 nm was then measured, and methanol instead of apple juice was used as a control. The value was calculated according to the following equation: DPPH free radical scavenging activity (%) = (1 − absorbance of sample/absorbance of control) × 100. This method was based on the previous study by Abid et al. (43).

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were replicated three times. All data in the present study were analyzed with SAS (version 9.4) (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) using Duncan’s multiple-range test. A significance level (P) of 0.05 was used to determine if there was a significant difference.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research has received financial support by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the government of the Republic of Korea (NRF-2018R1A2B2008825) and from the Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea (PJ0160822021).

Contributor Information

Dong-Hyun Kang, Email: kang7820@snu.ac.kr.

Edward G. Dudley, The Pennsylvania State University

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghate VS, Zhou W, Yuk HG. 2019. Perspectives and trends in the application of photodynamic inactivation for microbiological food safety. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 18:402–424. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silva AF, Borges A, Giaouris E, Graton Mikcha JM, Simões M. 2018. Photodynamic inactivation as an emergent strategy against foodborne pathogenic bacteria in planktonic and sessile states. Crit Rev Microbiol 44:667–684. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2018.1491528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durantini EN. 2006. Photodynamic inactivation of bacteria. Curr Bioact Compd 2:127–142. doi: 10.2174/157340706777435158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maisch T. 2015. Resistance in antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation of bacteria. Photochem Photobiol Sci 14:1518–1526. doi: 10.1039/c5pp00037h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hessling M, Spellerberg B, Hoenes K. 2017. Photoinactivation of bacteria by endogenous photosensitizers and exposure to visible light of different wavelengths–a review on existing data. FEMS Microbiol Lett 364:fnw270. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnw270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ercan D, Cossu A, Nitin N, Tikekar RV. 2016. Synergistic interaction of ultraviolet light and zinc oxide photosensitizer for enhanced microbial inactivation in simulated wash-water. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 33:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2015.11.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Çeşmeli S, Biray Avci C. 2019. Application of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles in cancer therapies. J Drug Targeting 27:762–766. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2018.1527338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziental D, Czarczynska-Goslinska B, Mlynarczyk DT, Glowacka-Sobotta A, Stanisz B, Goslinski T, Sobotta L. 2020. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles: prospects and applications in medicine. Nanomaterials 10:387. doi: 10.3390/nano10020387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Oliveira EF, Tosati JV, Tikekar RV, Monteiro AR, Nitin N. 2018. Antimicrobial activity of curcumin in combination with light against Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Listeria innocua: applications for fresh produce sanitation. Postharvest Biol Tec 137:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2017.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding Q, Alborzi S, Bastarrachea LJ, Tikekar RV. 2018. Novel sanitization approach based on synergistic action of UV-A light and benzoic acid: inactivation mechanism and a potential application in washing fresh produce. Food Microbiol 72:39–54. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gülçin İ. 2006. Antioxidant activity of caffeic acid (3, 4-dihydroxycinnamic acid). Toxicology 217:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura K, Ishiyama K, Sheng H, Ikai H, Kanno T, Niwano Y. 2015. Bactericidal activity and mechanism of photoirradiated polyphenols against Gram-positive and-negative bacteria. J Agric Food Chem 63:7707–7713. doi: 10.1021/jf5058588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura K, Yamada Y, Ikai H, Kanno T, Sasaki K, Niwano Y. 2012. Bactericidal action of photoirradiated gallic acid via reactive oxygen species formation. J Agric Food Chem 60:10048–10054. doi: 10.1021/jf303177p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilbert AR, Alborzi S, Bastarrachea LJ, Tikekar RV. 2018. Photoirradiated caffeic acid as an antimicrobial treatment for fresh produce. FEMS Microbiol Lett 365:fny132. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fny132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura K, Shirato M, Kanno T, Lingström P, Örtengren U, Niwano Y. 2017. Photo-irradiated caffeic acid exhibits antimicrobial activity against Streptococcus mutans biofilms via hydroxyl radical formation. Sci Rep 7:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07007-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balupillai A, Prasad RN, Ramasamy K, Muthusamy G, Shanmugham M, Govindasamy K, Gunaseelan S. 2015. Caffeic acid inhibits UVB‐induced inflammation and photocarcinogenesis through activation of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ in mouse skin. Photochem Photobiol 91:1458–1468. doi: 10.1111/php.12522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mota FL, Queimada AJ, Pinho SP, Macedo EA. 2008. Aqueous solubility of some natural phenolic compounds. Ind Eng Chem Res 47:5182–5189. doi: 10.1021/ie071452o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sperandio F, Huang Y-Y, Hamblin RM. 2013. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy to kill Gram-negative bacteria. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov 8:108–120. doi: 10.2174/1574891x113089990012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J, Lin S, Tan BK, Hamzah SS, Lin Y, Kong Z, Zhang Y, Zheng B, Zeng S. 2018. Photodynamic inactivation of Burkholderia cepacia by curcumin in combination with EDTA. Food Res Int 111:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamblin MR, O’Donnell DA, Murthy N, Rajagopalan K, Michaud N, Sherwood ME, Hasan T. 2002. Polycationic photosensitizer conjugates: effects of chain length and Gram classification on the photodynamic inactivation of bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 49:941–951. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogdan J, Zarzyńska J, Pławińska-Czarnak J. 2015. Comparison of infectious agents susceptibility to photocatalytic effects of nanosized titanium and zinc oxides: a practical approach. Nanoscale Res Lett 10:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s11671-015-1023-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamamoto A, Mori M, Takahashi A, Nakano M, Wakikawa N, Akutagawa M, Ikehara T, Nakaya Y, Kinouchi Y. 2007. New water disinfection system using UVA light‐emitting diodes. J Appl Microbiol 103:2291–2298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bintsis T, Litopoulou‐Tzanetaki E, Robinson RK. 2000. Existing and potential applications of ultraviolet light in the food industry–a critical review. J Sci Food Agric 80:637–645. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosshard F, Riedel K, Schneider T, Geiser C, Bucheli M, Egli T. 2010. Protein oxidation and aggregation in UVA‐irradiated Escherichia coli cells as signs of accelerated cellular senescence. Environ Microbiol 12:2931–2945. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss SH, Smith KC. 1981. Membrane damage can be a significant factor in the inactivation of Escherichia coli by near‐ultraviolet radiation. Photochem Photobiol 33:203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1981.tb05325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL. 2015. Oxidatively generated damage to cellular DNA by UVB and UVA radiation. Photochem Photobiol 91:140–155. doi: 10.1111/php.12368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Probst‐Rüd S, McNeill K, Ackermann M. 2017. Thiouridine residues in tRNAs are responsible for a synergistic effect of UVA and UVB light in photoinactivation of Escherichia coli. Environ Microbiol 19:434–442. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papuc C, Goran GV, Predescu CN, Nicorescu V, Stefan G. 2017. Plant polyphenols as antioxidant and antibacterial agents for shelf‐life extension of meat and meat products: classification, structures, sources, and action mechanisms. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 16:1243–1268. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campos F, Couto J, Figueiredo A, Tóth I, Rangel AO, Hogg T. 2009. Cell membrane damage induced by phenolic acids on wine lactic acid bacteria. Int J Food Microbiol 135:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haraguchi H, Tanimoto K, Tamura Y, Mizutani K, Kinoshita T. 1998. Mode of antibacterial action of retrochalcones from Glycyrrhiza inflata. Phytochemistry 48:125–129. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(97)01105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konishi K, Adachi H, Ishigaki N, Kanamura Y, Adachi I, Tanaka T, Nishioka I, Nonaka G-i, Horikoshi I. 1993. Inhibitory effects of tannins on NADH dehydrogenases of various organisms. Biol Pharm Bull 16:716–718. doi: 10.1248/bpb.16.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krug M, Chapin T, Danyluk M, Goodrich-Schneider R, Schneider K, Harris L, Worobo R. 2020. Outbreaks of foodborne disease associated with fruit and vegetable juices, 1922–2019. EDIS 2020. doi: 10.32473/edis-fs188-2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Food and Drug Administration. 2001. Hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP); procedures for the safe and sanitary processing and importing of juice. Fed Regist 66:6137–6202. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Islam MS, Patras A, Pokharel B, Wu Y, Vergne MJ, Shade L, Xiao H, Sasges M. 2016. UV-C irradiation as an alternative disinfection technique: study of its effect on polyphenols and antioxidant activity of apple juice. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 34:344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2016.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhavya M, Hebbar HU. 2019. Sono-photodynamic inactivation of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus in orange juice. Ultrason Sonochem 57:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho GL, Ha JW. 2020. Erythrosine B (Red Dye No. 3): a potential photosensitizer for the photodynamic inactivation of foodborne pathogens in tomato juice. J Food Saf 40:e12813. doi: 10.1111/jfs.12813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duthie GG, Duthie SJ, Kyle JA. 2000. Plant polyphenols in cancer and heart disease: implications as nutritional antioxidants. Nutrition Res Rev 13:79–106. doi: 10.1079/095442200108729016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma R. 2014. Polyphenols in health and disease: practice and mechanisms of benefits, p 757–778. In Watson RR, Preedy VR, Zibadi S (ed), Polyphenols in human health and disease. Elsevier, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Q, de Oliveira EF, Alborzi S, Bastarrachea LJ, Tikekar RV. 2017. On mechanism behind UV-A light enhanced antibacterial activity of gallic acid and propyl gallate against Escherichia coli O157: H7. Sci Rep 7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08449-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang J-W, Kim S-S, Kang D-H. 2018. Inactivation dynamics of 222 nm krypton-chlorine excilamp irradiation on Gram-positive and Gram-negative foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Food Res Int 109:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yam KL, Papadakis SE. 2004. A simple digital imaging method for measuring and analyzing color of food surfaces. J Food Eng 61:137–142. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(03)00195-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang J-W, Kang D-H. 2019. Increased resistance of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Escherichia coli O157: H7 to 222-nanometer krypton-chlorine excilamp treatment by acid adaptation. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e02221-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02221-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abid M, Jabbar S, Wu T, Hashim MM, Hu B, Lei S, Zhang X, Zeng X. 2013. Effect of ultrasound on different quality parameters of apple juice. Ultrason Sonochem 20:1182–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]