Abstract

Current antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are undesirable for many reasons including the inability to reduce seizures in certain types of epilepsy, such as Dravet syndrome (DS) where in one-third of patients does not respond to current AEDs, and severe adverse effects that are frequently experienced by patients. Epidiolex, a cannabidiol (CBD)-based drug, was recently approved for treatment of DS. While Epidiolex shows great promise in reducing seizures in patients with DS, it is used in conjunction with other AEDs and can cause liver toxicity. To investigate whether other cannabis-derived compounds could also reduce seizures, the antiepileptic effects of CBD, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabidivarin (CBDV), cannabinol (CBN), and linalool (LN) were compared in both a chemically-induced (pentylenetetrazole, PTZ) and a DS (scn1Lab−/−) seizure models. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) that were either wild-type (Tupfel longfin) or scn1Lab−/− (DS) were exposed to CBD, THC, CBDV, CBN, or LN for 24 h from 5 to 6 days postfertilization. Following exposure, total distance traveled was measured in a ViewPoint Zebrabox to determine if these compounds reduced seizure-like activity. Cannabidiol (0.6 and 1 μM) and THC (1 and 4 μM) significantly reduced PTZ-induced total distance moved. At the highest THC concentration, the significant reduction in PTZ-induced behavior was likely the result of sedation as opposed to antiseizure activity. In the DS model, CBD (0.6 μM), THC (1 μM), CBN (0.6 and 1 μM), and LN (4 μM) significantly reduced total distance traveled. Cannabinol was the most effective at reducing total distance relative to controls. In addition to CBD, other cannabis-derived compounds showed promise in reducing seizure-like activity in zebrafish. Specifically, four of the five compounds were effective in the DS model, whereas in the PTZ model, only CBD and THC were, suggesting a divergence in the mode of action among the cannabis constituents.

Keywords: Dravet syndrome, Cannabidiol, Pentylenetetrazole, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, Epilepsy, scn1Lab

1. Introduction

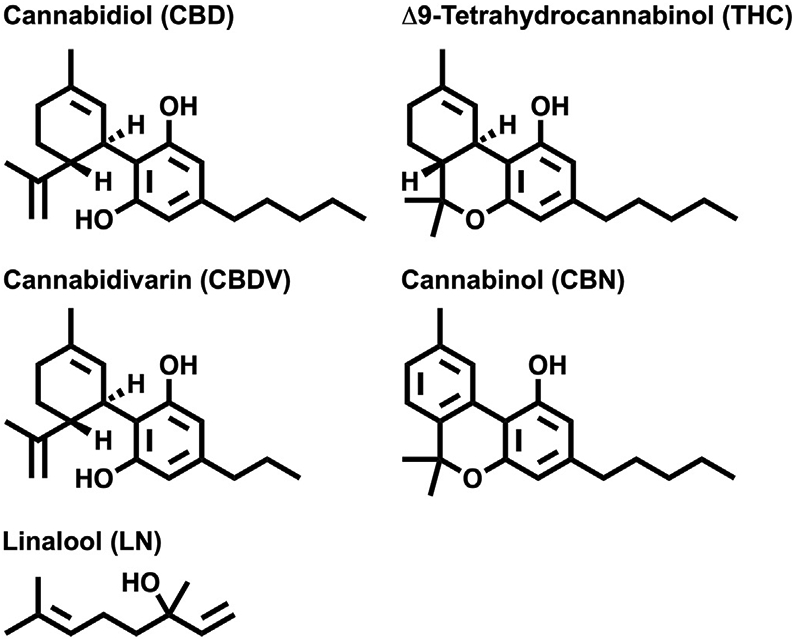

For thousands of years, Cannabis sativa has been used medicinally by humans. To date, there have been nearly 500 natural compounds identified or isolated from the Cannabis sativa plant [1]. Specifically, there are more than 100 phytocannabinoids and 200 terpenes found in cannabis, and many may possess anticonvulsant properties. Five of these constituents are the focus of this study (Fig. 1). The quantitative and qualitative components of the plant have plasticity as their composition, concentration, and yield are greatly affected by growing conditions [1]. In general, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the most common phytocannabinoid, wherein some varieties can contain up to 25% of tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) in dry weight [2]. Cannabidiol (CBD) is the second most common phytocannabinoid. Certain “CBD-heavy” strains, such as “Cannatonic”, have a 20:1 cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) to THCA ratio and peak dry weight concentrations approaching 17% CBDA [2]. Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid and CBDA are converted to THC and CBD with the addition of heat over time. Cannabinol (CBN) is a cannabinoid often formed following the oxidation of THC. Varieties considered high in CBN contain over 0.5% of the compound by dry weight [2]. Cannabidivarin (CBDV) is a propyl cannabinoid that naturally occurs in low proportions (<2%) [1]. Finally, linalool (LN) is one of the more common terpenes found in cannabis and can represent a significant portion (<6%) of the overall composition of the essential oils in the plant [3].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of cannabinoids: Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabidiol (CBD), cannabidivarin (CBDV), cannabinol (CBN), and linalool (LN).

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) scheduling of Epidiolex brought to market the first cannabis-based drug (>98% CBD) in the U.S. for the treatment of epilepsy. In the phase 3 clinical trials, Epidiolex significantly reduced seizure frequency compared with placebo in highly treatment-resistant patients [4]. As reviewed in ref. [5], CBD was efficacious for the patients with drop seizures associated with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome and was generally well-tolerated. Food and Drug Administration approval of Epidiolex opens the door for the potential development of more cannabis-based epilepsy drugs.

There are many different classifications or syndromes of epilepsy with some forms responding well to the current antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and other forms, such as Dravet syndrome (DS), that are intractable to traditional therapies. Currently, one-third of patients with epilepsy suffer from uncontrollable seizures because the available AEDs are ineffective [6]. Approximately 70–80% of DS cases are caused by a heterozygous loss-of-function mutation in the scn1a (sodium voltagegated channel alpha subunit 1) gene [7]. Patients with DS typically begin experiencing seizures in the first year of life, with frequent fever-related (febrile) seizures. Often as the disease progresses, the other types of seizures including myoclonus, absences, and complex partial seizures typically occur. Dravet syndrome is associated with a risk of lethality because of high incidence of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Estimates of mortality range from 15 to 20% before adulthood, with most premature deaths occurring before 10 years of age [8].

Traditionally, treatment of DS requires a combination of medications to treat the multiple types of seizures experienced by patients. These drug combinations often lack efficacy and cause severe adverse effects, including the following: liver damage, pancreatitis, and low blood platelet count. Furthermore, not all AEDs can be prescribed for children, which makes the management of DS even more difficult [9].

In addition to CBD, several other phytocannabinoids and terpenes produced by cannabis, including THC [10], CBDV [11-13], CBN [14], and LN [15-17], have displayed anticonvulsant potential in varying models of seizure and epilepsy. Thus, these compounds are of particular interest in our comparative study. Cannabidiol (summarized in ref. [5]) and formulations containing both CBD and THC (50:1) have been studied in patients with DS [18]. Prior to this study, CBDV, CBN, and LN had not been tested in any DS model to our knowledge. To compare the antiseizure potential of these five cannabis compounds in zebrafish, we utilized both chemically-induced (pentylenetetrazole (PTZ); a γ-aminobutyric acid receptor a (GABA-A) antagonist) and DS (scn1Lab mutant) models.

The utility of zebrafish for epilepsy research is growing rapidly because of several key advantages. Zebrafish have the ability to display seizure-like behavioral and neurophysiological responses by various pharmacological and genetic manipulations [19]. Approximately 84% of genes known to be associated with human diseases have a zebrafish counterpart identified. Therefore, zebrafish are considered a valuable resource in determining how genetic mutations affect neuronal activity and central nervous system development [20]. One of the best genetically derived zebrafish epilepsy models is for DS. Homozygous scn1Lab−/− mutants have significant phenotypic similarity to humans with DS, including spontaneously occurring seizures, resistance to many available AEDs, and early fatality [21,22]. The impacts on the pattern and swimming speed of both mutant larvae and adults can be readily quantified [23]. The goal for this study was to compare the efficacy of CBD, THC, CBDV, CBN, and LN in reducing seizure behavior in two mechanistically distinct models of epilepsy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Zebrafish husbandry

scn1Lab+/− fish (backcrossed with Tupfel longfin wild-type) were generously provided by Dr. Peter de Witte at the University of Leuven (Leuven, Belgium) and raised under the approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocol (19-001). scn1Lab−/− fish have a single point mutation in the scn1Lab gene resulting from chemical mutagenesis as described in ref. [24]. Fish were kept in Aquatic Habitats ZF0601 Zebrafish Stand-Alone System (Aquatic Habitats, Apopka, FL) with zebrafish water (pH 7.0–7.6, 340 parts per million (ppm), Instant Ocean, Cincinnati, OH) at 26–30 °C, 14:10 light–dark cycle. Fish were fed twice daily with Gemma Micro food (Skretting Nutreco Company, Westbrook, ME). Sexually mature fish without any deformities or signs of disease were selected as breeders. Embryos were collected from three to seven breeding events for the waterborne exposures described below and were raised to 5 days postfertilization (dpf) in embryo water (pH 7.5, 60 ppm Instant Ocean, 28 °C, 14:10 light–dark cycle) in petri dishes until the exposure began.

2.2. Waterborne exposure

At 5 dpf, scn1Lab−/− (DS model) and wild-type (scn1Lab+/+ or scn1Lab+/− (PTZ model)) healthy zebrafish larvae were transferred to a 96-well plate (1 larva/well; 4–12 fish/treatment/replicate plate; 3–7 replicate plates for a total of 8–43 fish per treatment with the exception of controls which were combined across all plates in the wild-type and DS models). Fish were randomly placed in each well from different clutches. The scn1Lab−/− larvae are distinguished by hyperpigmentation, noninflated swim bladder, slightly curved body axis, and spontaneous seizures. In this study, scn1Lab−/− larvae were chosen based on their hyperpigmentation phenotype [21]. A visual comparison between the two types of larvae is shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. The heterozygous scn1Lab+/− fish were utilized for the following two reasons: 1) to determine whether the compounds had sedative versus anticonvulsant effects and 2) for use in the chemically (PTZ)-induced seizure model. Exposure water (control (0.05% DMSO), CBD (0.25, 0.6, or 1.0 μM), THC (1.0 or 4.0 μM), CBDV (0.25, 0.6, 1, or 4 μM), CBN (0.25, 0.6, 1, or 4 μM), or LN (0.25, 0.6, 1, or 4 μM)) was added to each well (150 μL). Plates were covered with aluminum foil and placed in a 28 °C incubator for 24 h. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and CBD were provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Drug Supply Program (Research Triangle Park, NC). Cannabidivarin, CBN, and LN were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). The concentrations chosen for CBD and THC were based off concentrations utilized in [25] that did not cause significant deformities following a 96-h exposure. The concentrations chosen for CBDV, CBN, and LN were chosen to be similar to the CBD and THC concentrations used.

2.3. Behavioral screening

2.3.1. Dravet syndrome (scn1Lab−/− mutant)

Following 24 h of exposure, larvae (6 dpf) were screened for deformities including malformed body axis, pericardial edema, yolk sac edema, and lack of touch response. If a fish lacked touch response or if deformities were noted, it was excluded from behavioral analyses so as to not skew the perceived effectiveness of the drug because of their inability to swim normally. Mutant scn1Lab−/− larvae, unlike heterozygous fish (scn1Lab+/−), do not have inflated swim bladders. Therefore, all larvae included in the Dravet behavioral analysis had noninflated swim bladders. Following morphological deformity screening, larvae were placed in the Viewpoint Zebrabox (Civrieux, FR), allowed to acclimate for 5 min, and total distance was recorded for 15 min with 100% light (8000 lx). Representative videos of scn1Lab−/− untreated and 0.6-μM CBD larvae are shown in Supplemental Fig. 2.

2.3.2. Chemically-induced seizure

Following Dravet behavioral screening, the wild-type (scn1Lab+/+ and scn1Lab+/−) fish that were used as controls in the DS screening above were then treated with PTZ (Sigma-Aldrich; 50 μL of 20 mM for a final concentration of 5 mM) to induce seizures. All larvae included in a PTZ behavioral analysis had inflated swim bladders. Following 5-min incubation with PTZ, larval activity was reassessed in the Viewpoint Zebrabox to record total distance and movements for 15 min with 100% light (8000 lx). Representative videos of control, PTZ-treated, and PTZ + 0.6-μM CBD larvae are shown in Supplemental Fig. 3.

2.4. Statistics

Behavioral results were analyzed using SigmaPlot 14 (San Jose, CA) and presented as box and whisker plots. Datasets were first analyzed using the Grubb's Outlier test; outliers were subsequently excluded from analysis. Datasets were then tested for normality (Shapiro–Wilk) and equal variances (Brown–Forsythe) and analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the appropriate post hoc test, Dunnett's or Dunn's for normal or parametric or nonparametric distributions, respectively. Experimental groups were compared with control in the wild-type model, 5-mM PTZ control in the chemically-induced seizure model, or control (untreated seizures) in the DS model (p ≤ 0.05). Supplemental Table 1 provides average ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of total distance traveled, sample size, p values, and percent reduction compared with respective controls for each treatment group in each model.

3. Results

3.1. Toxicities

Following exposure, larvae were screened for toxicities including the following: lack of touch response, pericardial edema, yolk sac edema, body axis curvature, and mortality. Control larvae had less than a 5% incidence of deformities. Cannabinol (4 μM) and CBDV (4 μM) had 42% and 27%, respectively, of larvae that had at least one of the assessed developmental defects (Supplemental Table 2). All other treatment groups exhibited less than 13% incidence of toxicity. The 4-μM concentration of both CBN and CBDV was excluded from further behavioral analyses because of the high incidence of deformities.

3.2. Wild-type exposure

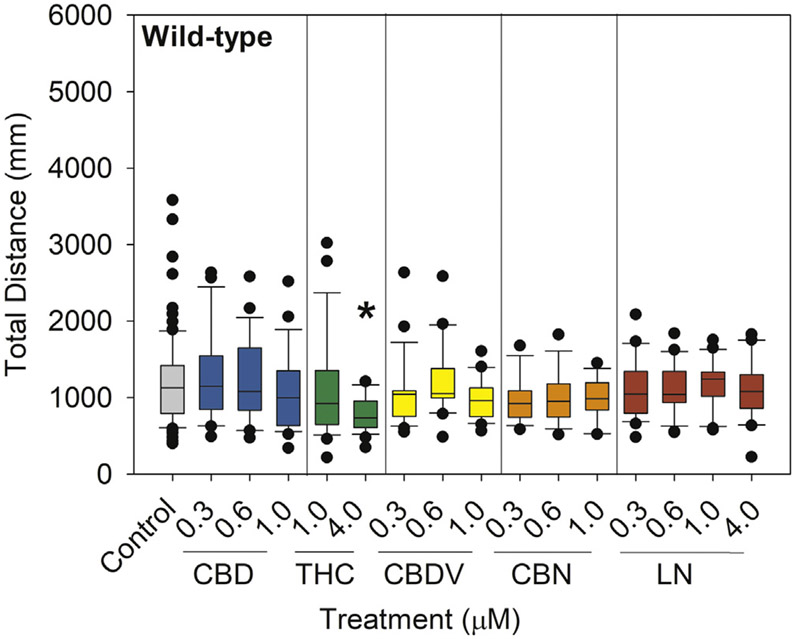

Locomotor behavior of wild-type larvae was observed to determine whether these compounds caused a sedative effect, which could confound seizure assessments. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (4 μM; 35.2% decrease) significantly reduced total distance traveled compared with controls (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Total distance traveled in wild-type (scn1Lab+/+ or scn1Lab+/−) larvae following a 24-h exposure from 5 to 6 dpf to 0.05% DMSO solvent control, CBD, THC, CBDV, CBN, or LN. Distance traveled was measured via Viewpoint Zebrabox for 15 min with 100% light (8000 lx). Data are plotted as box and whiskers plot with the horizontal line = median, box = 25–75%, and whiskers = bottom and top 25th percentiles. Treatment groups were compared with DMSO solvent controls with one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test (*p ≤ 0.05; n = 14–24 larvae per treatment with the exception of n = 86 for control).

3.3. Chemically-induced seizure

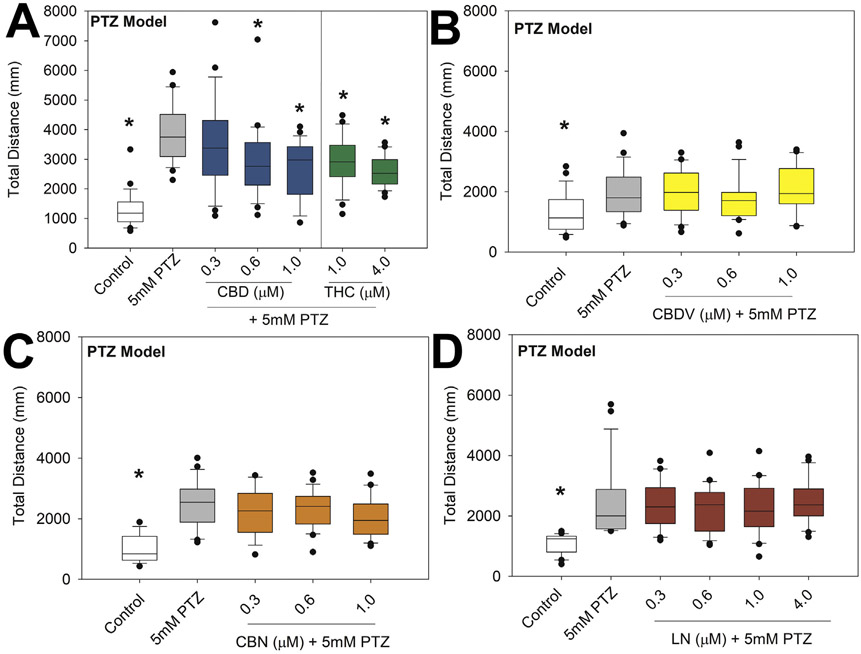

In wild-type larvae, PTZ-induced hyperlocomotion was significantly reduced following exposure to CBD (0.6 and 1 μM; 24.3 and 31.3% reduction; p = 0.034 and <0.001, respectively) or THC (1 and 4 μM; 24.8 and 32.1% reduction; p = 0.037 and 0.002, respectively), but no change was observed following CBDV, CBN, or LN exposure. Neither CBD nor THC reduced total distance to control levels (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Total distance traveled of PTZ-induced seizures following a 24-h preexposure from 5 to 6 dpf to 0.05% DMSO solvent control, CBD (A), THC (A), CBDV (B), CBN (C), or LN (D). Distance traveled was measured via Viewpoint Zebrabox for 15 min with 100% light (8000 lx). Data are plotted as box and whiskers plot with the horizontal line = median, box = 25–75%, and whiskers = bottom and top 25th percentiles. Treatment groups were compared with 5-mM PTZ group with one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test (*p ≤ 0.05; n = 15–24 larvae per treatment).

3.4. Dravet syndrome (scn1Lab−/− mutant)

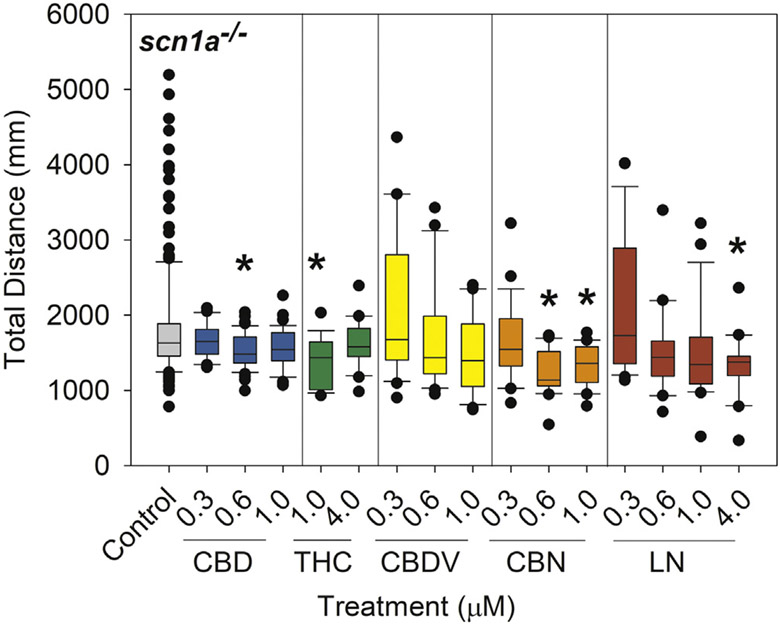

In the scn1Lab−/− mutants, total distance traveled was significantly reduced following exposure to CBD (0.6 μM; 16.6% reduction; p = 0.007), THC (1 μM; 23.3% reduction; p = 0.0017), CBN (0.6 and 1 μM; 31.7% and 25.9% reduction; p = < 0.001 and 0.007, respectively), and LN (4 μM; 26.6% reduction; p = 0.006) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Total distance traveled in DS (scn1Lab−/−) larvae following a 24-h exposure from 5 to 6 dpf to 0.05% DMSO solvent control, CBD, THC, CBDV, CBN, or LN. Distance traveled was measured via Viewpoint Zebrabox for 15 min with 100% light (8000 lx). Data are plotted as box and whiskers plot with the horizontal line = median, box = 25–75%, and whiskers = bottom and top 25th percentiles. Treatment groups were compared with DMSO solvent controls (untreated seizures) with one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test (*p ≤ 0.05; n = 20–47 larvae per treatment with the exception of n = 181 for control).

4. Discussion

Initially, we investigated whether the compounds tested would alter normal zebrafish larval activity. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (4 μM) significantly reduced total distance moved. Samarut and colleagues [26] saw a similar sedative effect in wild-type zebrafish with THC exposure at concentrations of 1, 2.5, and 3 μM. Therefore, reduction of total distance moved in the chemically-induced model following highest concentration THC exposure may be confounded by this observed sedative effect.

Pentylenetetrazole is a known convulsant that acts as a GABA antagonist [27]. Both our work and that of Samarut and colleagues [26] found CBD and THC significantly reduced PTZ-induced total distance moved. Furthermore, in their study, both CBD and THC (≥1.5 μM, 1-h exposure) reduced the total distance traveled back to control levels. For comparison, in our study, 4-μM THC, 24-h exposure, did not reduce total distance traveled to control levels, and concentrations above 1-μM CBD were not tested. One potential reason for the differences in the studies was the variable exposure times. Furthermore, extent of PTZ response varied across trials; for CBD and THC trials, the effect of PTZ alone was robust, but it was lower for CBDV, CBN, and LN treatments. Therefore, there was possibility of a false negative because of the lower relative range of response to observe these cannabinoids' ability to reduce the PTZ effects.

Despite CBDV not significantly reducing total distance traveled in the zebrafish PTZ model, it did significantly reduce PTZ-induced seizures as well as delayed onset of seizures in mice and rats [11-13]. Besides the difference in animal models between these studies, the dose used in our zebrafish model may not have been high enough to reduce the PTZ-induced seizures. Cannabidivarin has been tested in a phase 2 clinical trial. While initial clinical results were not statistically significant, GW Pharmaceuticals is continuing to investigate CBDV for therapeutic purposes [28].

In the present study, CBN did not reduce zebrafish PTZ-induced seizures. Existing data on CBN's antiseizure potential are limited. However, CBN did effectively reduce electroshock-induced seizures in mice though it was less effective than THC and CBD in that model [14]. Linalool also did not reduce PTZ-induced seizures in zebrafish. Conversely, De Sousa and colleagues [16] found that a racemic mixture of LN significantly reduced PTZ-induced seizures in mice that was comparable with that of diazepam. Essential oils containing LN decreased seizure severity and increased seizure latency in a PTZ-induced mouse model [17]. Additionally, in a case study, a patient taking THCA with high levels of α-LN had improved seizure control efficacy over a formulation of THCA without α-LN present [15].

The exact mechanisms by which cannabinoids like CBD exert their antiseizure effects are not well-understood, but there are a number of molecular targets thought to be modulated by CBD. For example, CBD is a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors [29,30] and therefore may be reducing seizures in both the PTZ-induced and DS models through this mechanism. Conversely, some studies have shown that THC inhibits GABA release [31,32] which may lead to worsening of seizures. In fact, THC has shown both anticonvulsant and proconvulsant properties depending on the seizure model and dose [10]. In this study, we found that following THC exposure in both the PTZ-induced (1 and 4 μM) and DS models (1 μM), total distance moved was significantly reduced. In a gabra1−/− zebrafish larvae seizure model, both CBD and THC significantly reduced seizure activity; however, much higher concentrations (>5 μM) were needed. This supports the idea that CBD and THC may alleviate seizures in part through GABA-A. To our knowledge, CBDV, CBN, and LN have not been associated with GABA-A, and therefore, that may explain why they were not effective in reducing seizures in the PTZ model.

In the DS model, we found that CBD, THC, CBN, and LN significantly reduced seizures with CBN being the most effective. While CBD efficacy in DS models is established [5], CBN and LN efficacy in a DS model is novel. Based on the results of our study, it is pertinent that cannabis producers focus on the production of strains that are “heavier” in CBD and CBN in order to facilitate further research on their anticonvulsant potential.

Decreased serotonin levels [33-35] and GABAergic dysfunction [36] have been implicated as underlying mechanisms in DS. Similar to the ability to modulate GABA-A receptors, CBD inhibits reuptake of serotonin [37]. Cannabidiol is a 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT2A partial agonist [30]. Acute increasing exposures to CBD in rats reduced the firing rate of 5-HT neurons; however, chronic, low-dose exposure to CBD increased 5-HT [38]. Cannabidiol and THC have been proposed to be serotonin 5-HT3A receptor antagonists [30]. Cannabidivarin, CBN, and LN have not been associated with serotonin signaling.

Another potential mechanism of action for these phytocannabinoids to reduce seizures could be via the TRPV1 (transient receptor potential vanilloid) channel. Cannabidiol, CBN, and CBDV are agonists of TRPV1 [30,39,40]. When wild-type mice were treated with CBDV, a significant reduction in tonic hindlimb extension was found; however, in CBDV-treated TRPV1 knockout mice, no significant reduction was observed, suggesting that CBDV may be TRPV1-dependent [13]. Furthermore, THC, CBD, CBN, and CBDV are all Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily A Member 1 (TRPA1) agonists [30,40]. Therefore, these phytocannabinoids could be reducing effects of DS seizures through binding to the TRPA1 receptor. Additionally, N-methyl-D-as-partate receptor (NMDA) [41,42], glycolysis [43-48], and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) [49,50] may be potential cannabinoid targets and contribute to effects on seizures.

An endpoint of interest in this study was potential toxicities of the five cannabis-derived compounds following 24 h of exposure including lack of touch response, pericardial edema, yolk sack edema, body axis curvature, and mortality. The only compounds that caused notable toxicity were CBDV and CBN both at a concentration of 4 μM. Cannabidivarin has genotoxic effects in human-derived cells [51]. However, in general, CBDV demonstrated significantly fewer adverse effects than currently approved AEDs in humans [28]. In mice, CBN altered male reproductive functions and caused neurotoxicity in male and female offspring [52]. Cannabinol did not cause significant changes or impacts on perception, emotion, cognition, and sociability in humans [53]. Clearly, more research is needed to elucidate the effects of these cannabis constituents following acute and chronic exposure in humans as would be needed for chronic control of seizures in patients with epilepsy. One limitation of this study was that behavior/larval activity was the endpoint measured. Others [21] have noted that larval activity alone could result in false positives, and therefore, electroencephalogram (EEG) can confirm reduced seizures.

In conclusion, cannabis constituents reduced seizure behavior in chemically-induced and scn1a-mutant zebrafish. Importantly, only CBD and THC were effective in the PTZ-induced model, whereas four of the five cannabis constituents were effective in the DS model. Epilepsy is an extraordinarily complicated disease with a broad spectrum of environmental and genetic risk factors; therefore, through genetic manipulation and high-throughput therapeutic screening, zebrafish can provide a robust platform for future studies aimed to delineate the divergent therapeutic mode of action of cannabis-derived treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by COBRE-National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) P20GM104932, COBRE-NIGMS P30GM122733-01A1, and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) R21DA044473-01. We would also like to thank Dr. Zacharias Pandelides and Patricia Lipson for their help in experimental design and statistics input.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107152.

Declaration of competing interest

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Pertwee RG. Handbook of cannabis. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Backes M. Cannabis pharmacy: the practical guide to medical marijuana. First. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Russo EB, Marcu J. Cannabis pharmacology: the usual suspects and a few promising leads. Adv Pharmacol. 2017;80:67–134. 10.1016/bs.apha.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thiele EA, Marsh ED, French JA, Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska M, Benbadis SR, Joshi C, et al. Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1085–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lattanzi S, Trinka E, Russo EB, Striano P, Citraro R, Silvestrini M, et al. Cannabidiol as adjunctive treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. Drugs Today. 2019;55:177–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Epilepsy Foundation. What is epilepsy. . https://www.epilepsy.com/learn/about-epilepsy-basics/what-epilepsy; 2019. [Accessed 1 June 2020]. .

- [7].Shmuely S, Sisodiya SM, Gunning WB, Sander JW, Thijs RD. Mortality in Dravet syndrome: a review. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;64:69–74. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cooper MS, Mcintosh A, Crompton DE, McMahon JM, Schneider A, Farrell K, et al. Mortality in Dravet syndrome. Epilepsy Res. 2016;128:43–7. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].National Organization of Rare Diseases. Dravet syndrome.. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/dravet-syndrome-spectrum/; 2019. [Accessed 1 June 2020]..

- [10].Devinsky O, Cilio MR, Cross H, Fernandez-Ruiz J, French J, Hill C, et al. Cannabidiol: pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia. 2014;55:791–802. 10.1111/epi.12631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hill A, Mercier M, Hill T, Glyn S, Jones N, Yamasaki Y, et al. Cannabidivarin is anticonvulsant in mouse and rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:1629–42. 10.1111/bph.2012.167.issue-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Amada N, Yamasaki Y, Williams CM, Whalley BJ. Cannabidivarin (CBDV) suppresses pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced increases in epilepsy-related gene expression. PeerJ. 2013;1:e214. 10.7717/peerj.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Huizenga MN, Sepulveda-Rodriguez A, Forcelli PA. Preclinical safety and efficacy of cannabidivarin for early life seizures. Neuropharmacology. 2019;148:189–98. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Karler R, Cely W, Turkanis SA. The anticonvulsant activity of cannabidiol and cannabinol, vol. 13; 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sulak D, Saneto R, Goldstein B. The current status of artisanal cannabis for the treatment of epilepsy in the United States. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;70:328–33. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].De Sousa DP, Nóbrega FFF, Santos CCMP, De Almeida RN. Anticonvulsant activity of the linalool enantiomers and racemate: investigation of chiral influence. Nat Prod Commun. 2010;5:1847–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Koutroumanidou E, Kimbaris A, Kortsaris A, Bezirtzoglou E, Polissiou M, Charalabopoulos K, et al. Increased seizure latency and decreased severity of pentylenetetrazol-induced seizures in mice after essential oil administration. Epilepsy Res Treat. 2013;2013:1–6. 10.1155/2013/532657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].McCoy B, Wang L, Zak M, Al-Mehmadi S, Kabir N, Alhadid K, et al. A prospective open-label trial of a CBD/THC cannabis oil in Dravet syndrome. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5:1077–88. 10.1002/acn3.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Stewart AM, Desmond D, Kyzar E, Gaikwad S, Roth A, Riehl R, et al. Perspectives of zebrafish models of epilepsy: what, how and where next? Brain Res Bull. 2012;87:135–43. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Griffin A, Krasniak C, Baraban SC. Advancing epilepsy treatment through personalized genetic zebrafish models. Prog. brain res Elsevier B.V; 2016. p. 195–207. 10.1016/bs.pbr.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Baraban Scott C, Dinday Matthew T, Hortopan Gabriela A. Drug screening in Scn1a zebrafish mutant identifies clemizole as a potential Dravet syndrome treatment. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2410. 10.1038/ncomms3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sourbron J, Partoens M, Scheldeman C, Zhang Y, Lagae L, de Witte P. Drug repurposing for Dravet syndrome in scn1Lab −/− mutant zebrafish. Epilepsia. 2019;60:e8–13. 10.1111/epi.14647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cunliffe VT. Building a zebrafish toolkit for investigating the pathobiology of epilepsy and identifying new treatments for epileptic seizures. J Neurosci Methods. 2016;260:91–5. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schoonheim PJ, Arrenberg AB, Del Bene F, Baier H. Optogenetic localization and genetic perturbation of saccade-generating neurons in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7111–20. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5193-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Carty DR, Miller ZS, Thornton C, Pandelides Z, Kutchma ML, Willett KL. Multi-generational consequences of early-life cannabinoid exposure in zebrafish. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2019;364:133–43. 10.1016/j.taap.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Samarut É, Nixon J, Kundap UP, Drapeau P, Ellis LD. Single and synergistic effects of cannabidiol and Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on zebrafish models of neuro-hyperactivity. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:226. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Walsh LA, Li M, Zhao TJ, Chiu TH, Rosenberg HC. Acute pentylenetetrazol injection reduces rat GABA(A) receptor mRNA levels and GABA stimulation of benzodiazepine binding with no effect on benzodiazepine binding site density. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:1626–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pharmaceuticals G. About us healthcare professionals patients & caregivers investors & media careers contact us home about us news GW Pharmaceuticals announces preliminary results of phase 2a study for its pipeline compound GWP42006.. https://www.gwpharm.com/about/news/gw-pharmaceuticals-announces-preliminary-results-phase-2a-study-its-pipeline-compound; 2018. [Accessed 1 March 2020]..

- [29].Bakas T, van Nieuwenhuijzen PS, Devenish SO, McGregor IS, Arnold JC, Chebib M. The direct actions of cannabidiol and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol at GABAA receptors. Pharmacol Res. 2017;119:358–70. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Morales P, Hurst DP, Reggio PH. Molecular targets of the phytocannabinoids: a complex picture. Prog Chem Org Nat Prod. 2017;103:103–31. 10.1007/978-3-319-45541-9_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Laaris N, Good CH, Lupica CR. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol is a full agonist at CB1 receptors on GABA neuron axon terminals in the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:121–7. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Renard J, Szkudlarek HJ, Kramar CP, Jobson CEL, Moura K, Rushlow WJ, et al. Adolescent THC exposure causes enduring prefrontal cortical disruption of GABAergic inhibition and dysregulation of sub-cortical dopamine function /631/378/2571 /631/378/1689/1799 /9 /9/30 /82 /82/1 article. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11420. 10.1038/s41598-017-11645-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Griffin A, Hamling KR, Knupp K, Hong SG, Lee LP, Baraban SC. Clemizole and modulators of serotonin signalling suppress seizures in Dravet syndrome. Brain. 2017;140:669–83. 10.1093/brain/aww342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sourbron J, Smolders I, de Witte P, Lagae L. Pharmacological analysis of the anti-epileptic mechanisms of fenfluramine in scn1a mutant zebrafish. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:191. 10.3389/fphar.2017.00191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Dinday MT, Baraban SC. Large-scale phenotype-based antiepileptic drug screening in a zebrafish model of Dravet syndrome. ENeuro. 2015;2:1–19. 10.1523/ENEURO.0068-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ruffolo G, Cifelli P, Roseti C, Thom M, van Vliet EA, Limatola C, et al. A novel GABAergic dysfunction in human Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia. 2018;00:1–12. 10.1111/epi.14574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pędracka M, Gawłowicz J. The role of cannabinoids and endocannabinoid system in the treatment of epilepsy. J Epileptol. 2015;23:131–8. 10.1515/joepi-2015-0034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [38].De Gregorio D, McLaughlin RJ, Posa L, Ochoa-Sanchez R, Enns J, Lopez-Canul M, et al. Cannabidiol modulates serotonergic transmission and reverses both allodynia and anxiety-like behavior in a model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2019;160:136–50. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Iannotti FA, Hill CL, Leo A, Alhusaini A, Soubrane C, Mazzarella E, et al. Nonpsychotropic plant cannabinoids, cannabidivarin (CBDV) and cannabidiol (CBD), activate and desensitize transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channels in vitro: potential for the treatment of neuronal hyperexcitability. ACS Chem Nerosci. 2014;5:1131–41. 10.1021/cn5000524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].De Petrocellis L, Ligresti A, Moriello AS, Allarà M, Bisogno T, Petrosino S, et al. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1479–94. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sánchez-Blázquez P, Rodríguez-Muñoz M, Garzón J. The cannabinoid receptor 1 associates with NMDA receptors to produce glutamatergic hypofunction: implications in psychosis and schizophrenia. Front Pharmacol. 2014;4:169. 10.3389/fphar.2013.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rosa-Falero C, Torres-Rodríguez S, Jordín CC, Licier R, Santiago Y, Toledo Z, et al. Modulation of PTZ induced seizures by Citrus aurantium in zebrafish: role of NMDA and metabotropic glutamate receptors. Front Pharmacol. 2015;5:284. 10.3389/fphar.2014.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kumar MG, Rowley S, Fulton R, Dinday MT, Baraban SC, Patel M. Altered glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration in a zebrafish model of Dravet syndrome. ENeuro. 2016;3. 10.1523/ENEURO.0008-16.2016 e008 = 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gano LB, Patel M, Rho JM. Ketogenic diets, mitochondria, and neurological diseases. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:2211–28. 10.1194/jlr.R048975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Vehmeijer FOL, Van Der Louw EJTM, Arts WFM, Catsman-Berrevoets CE, Neuteboom RF. Can we predict efficacy of the ketogenic diet in children with refractory epilepsy? Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2015;19:701–5. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nangia S, Caraballo RH, Kang HC, Nordli DR, Scheffer IE. Is the ketogenic diet effective in specific epilepsy syndromes? Epilepsy Res. 2012;100:252–7. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Taylor MR, Hurley JB, Van Epps HA, Brockerhoff SE. A zebrafish model for pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency: rescue of neurological dysfunction and embryonic lethality using a ketogenic diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4584–9. 10.1073/pnas.0307074101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Yu L, Chen C, Wang LF, Kuang X, Liu K, Zhang H, et al. Neuroprotective effect of kaempferol glycosides against brain injury and neuroinflammation by inhibiting the activation of NF-κB and STAT3 in transient focal stroke. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55839. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Naziroğlu M, Taner AN, Balbay E, Çiğ B. Inhibitions of anandamide transport and FAAH synthesis decrease apoptosis and oxidative stress through inhibition of TRPV1 channel in an in vitro seizure model. Mol Cell Biochem. 2019;453:143–55. 10.1007/s11010-018-3439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Colangeli R, Pierucci M, Benigno A, Campiani G, Butini S, Di Giovanni G. The FAAH inhibitor URB597 suppresses hippocampal maximal dentate after discharges and restores seizure-induced impairment of short and long-term synaptic plasticity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11152. 10.1038/s41598-017-11606-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Russo C, Ferk F, Mišík M, Ropek N, Nersesyan A, Mejri D, et al. Low doses of widely consumed cannabinoids (cannabidiol and cannabidivarin) cause DNA damage and chromosomal aberrations in human-derived cells. Arch Toxicol. 2019;93:179–88. 10.1007/s00204-018-2322-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Dalterio S, Steger R, Mayfield D, Bartke A. Early cannabinoid exposure influences neuroendocrine and reproductive functions in male mice: I prenatal exposure. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1984;20:107–13. 10.1016/0091-3057(84)90110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kariniol IG, Shirakawa I, Takahashi RN, Knobel E, Musty RE. Effects of delta 9-tetrahydrocannibinol and cannabinol in man. Pharmacology. 1975;13:502–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.