Abstract

Using data from the Relationship Dynamics and Social Life Study, a diverse sample of 925 women updated weekly for 2.5 years, I (1) describe how desire for sex varies across and within women during the transition to adulthood; (2) explore how desire corresponds with women’s social circumstances and experiences; and (3) assess the relationship between desire for sex, sexual activity, and contraceptive use. The strength of young women’s desire is heterogeneous across key demographic characteristics like religiosity and social class; changes after pivotal events like sexual debut; and varies with social ecology, such as friends’ attitudes. When women more strongly desire sex they are more likely to have sex and to use hormonal contraception. Moreover, the association between desire and sex is especially pronounced when women are using a hormonal method. In contrast, when women more strongly desire sex they are less likely to use condoms or withdrawal, irrespective of hormonal use. These findings suggest that sexual desire is socially situated and relevant for both anticipatory and situational decisions about contraception. Foregrounding this desire thus greatly expands scholarly conceptualizations of women’s sexual agency, young adult sexuality, and cognitive social models of sexual decision-making.

Keywords: Sexuality, Transition to Adulthood, Sex/Gender, Social Psychology, Sexual and Reproductive Health

Introduction

For more than three decades, adolescent and young adult sexuality has been a flourishing area of inquiry (Brooks-Gunn and Furstenberg Jr 1989; Haydon et al. 2012; Tolman and McClelland 2011). Within this area, one of the most common themes has been the risks associated with sex, namely early and unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Cederbaum et al. 2015; Diaz and Fiel 2016; Furstenberg Jr 2003; Geronimus and Korenman 1993; Rosenberg et al. 1999). Because women’s sexuality has historically been the subject of substantial social control and their perceived desire a source of stigma (Armstrong et al. 2014; Browning, Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2005; Fjær, Pedersen and Sandberg 2015; Gordon 2002), scholars have also debated whether young women’s sexual activity undermines their mental health (Armstrong, Hamilton and England 2010; Bersamin et al. 2014; Eisenberg et al. 2009; Meier 2007). Yet many women view sex as a source of pleasure and intimacy (Armstrong, England and Fogarty 2012; Higgins, Hirsch and Trussell 2008), and may therefore want to have sex despite the associated stigma and risks. This desire may be central to their behavior—a possibility that remains neglected within the literature on adolescent and young adult sexuality. In response to this paucity, this study asks: How much do young women want to have sex during the transition to adulthood? Are women’s desires for sex shaped by their social circumstances? And, how are women’s sexual and contraceptive behaviors related to their desire?

Answering these questions advances extant scholarship in three ways. First, by overemphasizing young women’s sexuality in terms of its associated risks, existing research has implicitly portrayed young women as sexually passive, unreasonable, and irresponsible (Diamond 2014). Foregrounding that some women want to have sex fundamentally shifts the way scholars conceptualize and discuss women’s sexuality by recognizing women as cognizant individuals with the potential to act as agents of their own desires.

Second, the paucity of attention to women’s sexual desire in social scientific literature perpetuates the misconception that desire for sex is an exclusively biological phenomenon (e.g. hormonal sex drive). In reality, this desire has social dimensions as well, such as the sociocultural valuation of sexual expression and relational motivations (Levine 2003). Employing social ecological and life course frameworks (Bronfenbrenner 2009; Elder and Rockwell 1979), I show that women’s desires are deeply embedded in their social contexts, from their friends and family to their intimate relationships and school enrollment, and that desire for sex is further influenced by pivotal events like sexual debut.

Third, neglecting to connect women’s sexual behavior and contraceptive use to their underlying desire for sex oversimplifies the process by which women make consequential decisions about their fertility and reproductive health (Barber 2011). Because sex often yields physical and emotional satisfaction (Armstrong, England and Fogarty 2012; Regan and Dreyer 1999), desire for it may influence decisions that could jeopardize women’s wellbeing. However, because of the inherent risks associated with unprotected sex, underlying desire may also affect deliberate risk-mitigation via advanced planning that enables stress-free, in-the-moment sexual encounters. Examining the relationship between desire for sex and young adults’ sexual and reproductive behavior thus provides an important opportunity to more fully integrate and test cognitive social models of decision-making into the study of sexuality.

To investigate young women’s desire for sex and how this desire relates to subsequent behavior, I leverage panel data from the Relationship Dynamics and Social Life study (RDSL), which provide information on women’s desire for sex every three months and their sexual and contraceptive behaviors every week for 2.5 years. Critical to this study, RDSL data also include demographic information collected in a baseline survey and additional time-varying information on relationship status, attitudes, and social environments. These data uniquely facilitate (1) a novel description of how desire for sex varies across young women and changes as they enter adulthood, (2) an examination of how desire corresponds to women’s social circumstances, and (3) an assessment of co-variation between desire for sex and sexual and contraceptive behavior. Additional information on women’s sexual orientation collected though a one-time supplemental survey further allows me to test the robustness of the main findings to the exclusion of non-hetero and non-bisexual women.

Background

It is widely accepted that desires such as desire for children (Hayford 2009; Weitzman et al. 2017) or schooling (Frye 2012; Sewell and Shah 1968) are socially determined. Studies of these desires suggest that desires correspond to various dimensions of one’s social environment, from family context and perceived norms among peers to media propaganda (Frye 2012; Weitzman et al. 2017). Yet the same conceptualization of social determination has rarely been extended to desire for sex, leading scholars to sometimes reduce it to sex drive (Regan 1996; Stanislaw and Rice 1988).

Sex drive is the only biological dimension of desire for sex (Levine 2003), which possesses two additional sociological dimensions: sociocultural values associated with sexual expression and individual and/or relationship-derived, social psychological motivation (Levine 2003). In the sections that follow I elaborate how these sociological dimensions relate to young women’s social circumstances and interpersonal relationships. Then I draw on cognitive research to illustrate how and why young women’s desire for sex is likely to affect decisions to have sex, use hormonal contraception in advance of having sex, and use condoms or withdrawal at the time of sex.

The Social Ecology and Evolution of Desire during the Transition to Adulthood

According to the social ecological perspective of human development (Bronfenbrenner 2009), individuals sit at the nucleus of and are deeply influenced by the social environment that surrounds them. This environment consists of several layers: the micro and meso, where everyday interactions take place with family, friends, and partners, and where such actors form connections with each other; the exo, where institutions structure the connections made in the meso, such as neighborhoods or schools; and the macro, consisting of diffuse knowledge, resources, and cultural norms. According to the life course perspective (Elder 1995; Elder 1997), however, individuals’ social ecology is not static, nor does it simply influence them at one point in time. Rather, because a woman’s social ecology affects her thinking and behavior in a given moment it necessarily also influences her social pathways and developmental trajectories, thereby shaping her subsequent ideation, behavior, and social ecologies. Social ecological and life course frameworks, together, indicate that women’s desires should be influenced by their prior experiences, co-evolve with their social circumstances, and further shape their future trajectories.

Both perspectives suggest that how much women value sexual expression—the first sociological dimension of desire—should be closely related to the attitudes and values they possess. Furthermore, they suggest that these attitudes and values should arise from the social environment. However, the relationship between attitudes, values, and desires is complicated by the fact that, as the life course perspective suggests (Elder and Rockwell 1979), attitudes and desires shift over time. For example, depending on how much a woman enjoys her first sexual experience, her desire may subsequently increase or decrease (Impett, Muise and Breines 2013). Moreover, independently of enjoyment, desire for sex may increase after sexual debut if women align their desire with their behavior to avoid cognitive dissonance (Lindgren et al. 2011).

At the micro level, interactions with partners, peers, and family reinforce sociocultural values. For example, women who are surrounded by sexually active individuals or individuals who are accepting of sex are more likely to have sex (Jackson 2005; Tolman and McClelland 2011), either because they perceive it as acceptable or because they want to have sex as a way of adhering to established norms and expectations. Moreover, women whose friends are older or sexually active (Cavanagh 2004; Sieving et al. 2006) and whose friends and parents approve of sex tend to have sex at younger ages (Davis and Friel 2001). Consistent with the life course perspective, these patterns indicate that young women’s timing of sexual debut is closely tied to the sexual norms and/or perceived permissibility of sex within their social environments.

At the exo level, institutional contexts such as religion and school structure linkages between micro actors, thereby contributing to the diffusion of norms, attitudes, and desires. If one dimension of sexual desire is valuing sexual expression, then institutionalized sexual norms should influence how much or how little women desire sex. For instance, highly religious women tend to report lower desire for sex (Barber, Yarger and Gatny 2015), potentially because many religions espouse conservative sexual attitudes which discourage sexual expression. College environments, on the other hand, tend to be accepting of non-marital sex. In fact, a “hook up” culture involving casual sex and other sex acts is well documented among college students (England, Shafer and Fogarty 2007; Grello, Welsh and Harper 2006). Moreover, among college-goers, condom use declines precipitously after the first year, suggesting that most students converge to a norm of non-condom use as they progress through their college career (Bearak 2014). If sexual activity in college environments reflects a climate of normalized casual sex and sexual permissiveness, and if young women perceive pressure to adhere to sexual norms, then attending college may increase young women’s desire for sex via desires to convey an adherence to sociocultural norms.1

Research on the transition to adulthood suggests that women’s desires, including their desire for sex, should be especially susceptible to the social environments that surround them at this stage of the life course. For instance, this period tends to be marked by a dense concentration of sexual experimentation and the formation of new friendships and relationships (Giordano, Longmore and Manning 2001; Graber, Brooks-Gunn and Petersen 1996)—experiences that may sway women’s valuation of sexual expression. In addition, it corresponds with the end of adolescence—a developmental period in which young individuals are typically concerned with the opinions of others while also subject to peer pressure (Martin 1996; Tolman 2009). If desire for sex is partially driven by a motivation to adhere to sexual norms at this stage (Prinstein, Meade and Cohen 2003; Schachner and Shaver 2004), even despite sexual double standards, then it need not be acute. In other words, a teenage woman who wants to have sex because all her friends are doing it does not necessarily want to have sex tomorrow but may instead have a more nebulous desire to have sex within the next year. This theoretical distinction is critical given that desire for sex has almost exclusively been conceived of as acute (Beck, Bozman and Qualtrough 1991; Goldey and van Anders 2012; Moholy et al. 2015).

Individual and Relational Social Psychological Motivations

The second sociological dimension of desire for sex is individual or relationship-derived, social psychological motivation. There are many individual-level motivations for sex. For instance, many women experience sex as a pleasurable physical occurrence that they want to enjoy more of (Armstrong, England and Fogarty 2012).2 Some women also derive emotional satisfaction from sex, including a sense of intimacy and romance (Schachner and Shaver 2004), feeling wanted and desired (Meston and Buss 2007), or feeling in control of their sexual subjectivity (Tolman 2009). Others want to have sex because they want to become pregnant, though this is less common among younger women (Levine 2003). In terms of relationship-derived motivation, women may want to have sex because they want to please their partners (Klusmann 2002) or because they believe sex fosters intimacy (Schachner and Shaver 2004) or is important to maintaining their relationships (Impett and Peplau 2003).

There are also several reasons why women may not want to have sex. For example, among particularly risk-averse women, the desire to avoid pregnancy or fear of contracting an STI may deflate desire (Blinn-Pike 1999). Alternatively, some women may fear being stigmatized for having or wanting sex (Armstrong et al. 2014), especially if they and those around them possess conservative sexual attitudes.

Because individual and relational motivations for sex are primarily related to the satisfaction gained from it, this dimension likely contributes to more immediate desires. For example, women who view sex as essential to maintaining a healthy romantic relationship may desire sex weekly with their partner when they are in a relationship, rather than more abstractly within the next year.

Desire and Decision-Making

While an abundance of research documents a relationship between fertility desire and reproductive behavior (Miller, Barber and Gatny 2013; Miller, Barber and Schulz 2017; Rosengard et al. 2004; Thomson 1997), little investigates the relationship between young women’s sexual desire and behavior. Yet because sexual desire reflects a wanting and/or liking of sex, it is likely consequential to important decisions women make with respect to their sex lives. Explicitly examining how women’s behavior relates to their underlying desire for sex, thereby recognizing women as multidimensional beings whose behavior may be motivated by a range of different desires (Barber 2011; Barber 2001), thus provides a more complete portrait of sexual and reproductive decision-making.

Psychological research indicates that individuals have two cognitive processes or “systems” that affect decision-making (Evans 2003; Evans 2008; Hofmann, Friese and Strack 2009; Kahneman 2003), both of which may be influenced by people’s desires. One system is deliberate, logical, and calculated. In particular, it is used for estimating probabilities, whether implicitly or explicitly. Thus, to the extent that desire for sex affects a future-oriented intention to have sex (Ariely and Loewenstein 2006; Loewenstein, Nagin and Paternoster 1997), this desire may influence deliberate cognition (Miller 1994).3 Intentions to have sex could in turn stimulate the estimation of potential risks and benefits of sex and/or contraceptive use in advance of sexual situations (Evans 2003; Kőszegi and Rabin 2006; Tversky and Kahneman 1992). If through this process a woman deduced that sex without contraception disproportionately yielded undesirable threats to her wellbeing, then she could also deduce a plan to offset these threats in advance (Wolfs et al. 2018). For instance, if a woman worried about becoming pregnant but wanted to have sex, she could plan to use hormonal contraception. Behaviorally, this should translate into a higher likelihood of hormonal contraceptive use amidst stronger desires for sex, at least among some women. Reciprocally, if women use hormonal contraception because they anticipate having sex and want to mitigate the risk of unwanted pregnancy, then desire for sex should have a stronger effect on the likelihood of intercourse when women are using hormonal methods compared to when they are not.

Likewise, if a woman was concerned about STI contraction, deliberate planning triggered by desire for sex could lead her to regularly carry condoms and to therefore be prepared for both unanticipated and anticipated sexual encounters (Wolfs et al. 2018). However, deliberate cognition requires substantial effort (Evans 2003; Kahneman 2003), making it difficult for individuals to always comply with their plans, especially when under pressure or facing time constraints (Finucane et al. 2000). Desire for sex may therefore not necessarily translate into a higher likelihood of coital contraceptive use, which requires the enactment of deliberate behaviors in the heat of the moment.

Relatedly, the second cognitive system is automatic and guided by intuition. Because intuition is based on affect (Slovic et al. 2007; Slovic et al. 2002), automatic cognition is especially susceptible to what psychologists refer to as “framing effects” (Kahneman 2003; McElroy and Seta 2003). In other words, automatic cognition is biased by whether a situation is presented with respect to prospective gains or losses. Because desire for sex reflects the possession of positive affect toward it, e.g. that a woman likes sex or at least the idea of it, sexual desire may contribute to automatic decisions about sex.4 Moreover, some affective states, like arousal or craving, make temptations especially difficult to resist (Ariely and Loewenstein 2006; Loewenstein, Nagin and Paternoster 1997; Slovic et al. 2007). Because affect biases intuition, when a woman wants to have sex her view of the potential satisfaction gained by sexual opportunities may outweigh her perception of the potential threats even if she does not have contraception available. In fact, one study documents this possibility among men (Blanton and Gerrard 1997).

Cognitive research on deliberate and automatic processing, in sum, implies four behavioral consequences of desiring sex. First is that young women should be more likely to have sex when they desire it. A handful of studies conducted among men and focusing on sexual arousal (an acute, heightened state of desire) support this possibility (Ariely and Loewenstein 2006; Loewenstein, Nagin and Paternoster 1997). Second is that the relationship between desire and sexual activity should be stronger when women are using hormonal contraception than when they are not. This assumes that most young women want to avoid pregnancy (Weitzman et al. 2017) and that hormonal contraception is primarily taken to avoid pregnancy (rather than for other medical purposes). Third and relatedly is that women should be more likely to use hormonal contraception when they desire sex because this desire stimulates sexual forethought and planning, including the use of hormonal contraception as a pregnancy-avoidance strategy. Fourth, because sexual desire should reduce impulse control in the heat of the moment, and because coital contraception is often viewed as an impediment to sexual pleasure and intimacy (Higgins and Hirsch 2008), desire for sex should be negatively associated with coital contraceptive use. Indeed, at least one study finds that HIV positive men report stronger intentions to have unprotected sex when they are sexually aroused than when they are not (Shuper and Fisher 2008). Examining how sexual desire relates to young women’s sexual and contraceptive behavior thus broadens and complicates longstanding conceptualizations of how young women make decisions about their sexual and reproductive health.

Data and Methods

Data

Sample.

I use data from the Relationship Dynamics and Social Life (RDSL) study, which followed a population-representative sample of 1,003 18 and 19 year old women for 2.5 years. Respondents were randomly selected from the Department of State’s driver’s license and Personal Identification Card database in one racially and socioeconomically diverse Michigan county and enrolled between 2008 and 2009.5

Figure 1 illustrates the timeline of RDSL data collection. The study began with a comprehensive baseline survey that included questions about respondents’ desire for sex, personal attitudes, previous sexual experiences, educational enrollment, sexual norms and perceived approval among friends and family, and demographic background. Upon completion, respondents were invited to participate in the journal portion of the study, which consisted of 5-minute weekly surveys online or by phone for the following 30 months. 992 respondents (99%) completed these weekly journals, which included repeated questions about relationship status, intercourse, contraception, and fertility intentions (Figure 1).6 Every twelve weeks, the weekly journal was accompanied by a brief supplement that reassessed desire for sex, personal attitudes, educational enrollment, sexual norms and perceived approval among friends and family (Figure 1). A randomized experiment conducted during the RDSL indicated that repeatedly answering these questions had little to no effect on women’s reported outlook or behavior (Barber, Gatny and Kusunoki 2012).

Figure 1:

Timeline of RDSL Assessments

In addition to the baseline, weekly, and quarterly surveys, the RDSL included several one-time supplements. These supplements were administered separately from the journal, and, because enrollment in the RDSL was staggered, they included fewer respondents. In one, conducted in 2010, 590 respondents were asked about their sexual orientation. In another, conducted in 2011, 561 respondents were asked a series of questions about their sexual appetite (Figure 1). I use information from these supplements to conduct a series of sensitivity analyses, discussed below.

Because this analysis examines both young women’s sexual desire and their sexual and contraceptive behavior, I focus the analysis on respondents who completed two or more journals and on weeks in which respondents were not pregnant. This yields a final sample of 54,068 weeks among 925 respondents.

Measures

Sex and Contraceptive Use.

Each week, respondents were asked a series of questions to determine if they had had any kind of partner with whom they’d had “physical or emotional contact.” If so, they were asked to provide that partner’s initials. Then they were asked “….did you have sexual intercourse with [partner]? By sexual intercourse, we mean when a man puts his penis into a woman’s vagina.” And “…did you have sexual intercourse with anyone other than [partner]?” Based on responses to these two questions, I create a dichotomous indicator of whether respondents (1) had sexual intercourse in a given week or (0) not. Weeks when respondents did not report having a partner are coded (0) did not have sexual intercourse. Respondents had intercourse in one-third of weeks in the study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Mean/proportion | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex and contraceptive use | ||

| Had intercourse | .33 | |

| …and used no contraception | .14 | |

| …and used hormonal contraception only | .32 | |

| …and used coital contraception only | .37 | |

| …and used hormonal and coital contraception | .17 | |

| Used hormonal contraception | .33 | |

| Desire for sex | ||

| Desire for sex (0–5) | 2.76 | 1.80 |

| Personal attitudes and intentions | ||

| Approval: premarital sex (1–5) | 3.04 | 1.31 |

| Approval: casual sex with friends (1–5) | 2.22 | 1.12 |

| Wants to get pregnant | .07 | |

| Previous experiences and age | ||

| Sexual debut <=14 years† | .12 | |

| Ever had sex | .74 | |

| Cumulative no. of sex partners (0–64) | 4.78 | 5.23 |

| Cumulative no. of live births (0–4) | .15 | .42 |

| Age (18–22) | 20.29 | .94 |

| Relationship context | ||

| Relationship status (ref: none or casual) | ||

| Married | .03 | |

| Engaged | .08 | |

| Special | .45 | |

| Relationship duration (0–133 weeks) | 11.62 | 17.77 |

| Friends context | ||

| Friends’ approval of sex (0–5) | 2.88 | 1.30 |

| Proportion of friends sexually active (1–5) | 4.10 | 1.13 |

| Family context and race | ||

| Parents’ approval of sex (0–5) | 1.83 | 1.35 |

| Mother <20 at first birth† | .28 | |

| Mother’s education (ref: <H.S.) † | ||

| Completed H.S. | .67 | |

| Completed college | .27 | |

| Received public assistance as a child† | .31 | |

| African American† | .27 | |

| Institutional contexts | ||

| School | ||

| Enrolled in college | .73 | |

| Religion | ||

| Highly religious† | .56 | |

| Frequency of religious attendance (0–5) † | 3.15 | 1.73 |

Note: N= 54,068 weeks (among 925 respondents)

Measure was assessed once at baseline and therefore does not vary within respondents over time.

Every week respondents were also asked “Did you use or do anything that can help people avoid becoming pregnant, even if you did not use it to keep from getting pregnant yourself?” When a respondent answered “yes” she was asked a series of follow-up questions about hormonal methods, including oral contraceptive pills, transdermal patch, vaginal rings, injectable contraceptives, implant, and IUD. Used hormonal contraception is defined (1) when a respondent reported using any of these methods and (0) otherwise.

In weeks when a respondent reported sexual intercourse she was asked a second set of questions about her use of coital-specific methods. Used coital contraception is defined (1) when a respondent reported using a condom (male or female) or that her partner withdrew before ejaculating and (0) otherwise.7

Desire for Sex.

During the baseline survey respondents were asked, “How much do you want to have sexual intercourse in the next year? Please give a number between 0 and 5 where (0) means not at all and (5) means extremely.” This question was asked again every twelve weeks during the journal portion of the study. Responses were carried forward between weeks when the question was re-asked. I treat this measure as interval-level. A sensitivity test treating each level as a discrete category confirms that desire for sex has a monotonic effect.

The biggest weakness of this measure is that it was asked with respect to a wide interval of time: the next year. To better understand if it also partially captured respondents’ desire in a more immediate sense, I explore correlations with nine questions asked about respondents’ sexual appetite. This module of questions was included in a one-time supplement in 2011, toward the closing of the RDSL (Figure 1), and was adapted from the Hurlbert Index of Sexual Desire (Apt and Hurlbert 1992) and the Sexual Inhibition/Sexual Excitation for Women Scale (Graham, Sanders and Milhausen 2006; Graham et al. 2004). Specifically, women were asked to respond “true” or “false” to the following statements: “Just thinking about sex excites me.” “I daydream about sex.” “I look forward to having sex.” “I have a huge appetite for sex.” “I enjoy thinking about sex.” “I often desire sex.” “I want sex less than most people,” (which I reverse code), “I have a strong sex drive,” and “Once I am aroused, or turned on, it is extremely difficult to stop myself from having sex.” Figure 2 graphs the percent of women providing affirmative answers to each question by how much they reported wanting to have sex in the next year. Because this supplement was administered after the majority of respondents had completed the journal-portion of the study (and toward the end of participation for those still enrolled), this graph relies on respondents’ last assessment of desire for sex in the RDSL. As can be seen in this figure, desire for sex in the upcoming year is highly correlated with each of these measures. For example, 60% of respondents who had an “extreme” desire for sex in the next year also reported having “a strong sex drive”. In contrast, only 13% of women with no desire for sex in the next year answered this question affirmatively (Figure 2). These correlations thus suggest that desire for sex, as measured quarterly in the RDSL, partially reflects immediate desires despite that it is asked about with respect to a wider time horizon.

Figure 2:

Prevalence of Sexual Appetite Items, by Desire for Sex

Note: N=561 respondents who completed the supplementary survey including true/false questions about the above statements. Results of chi-square tests denoted by asterisks.

*** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05

Personal Attitudes and Intentions.

To capture attitudes toward sex, respondents were asked to respond to the following two statements: “young people should not have sex before marriage” and “it is alright for young people to have premarital sex even if they are just friends.” Possible responses ranged from (1) “strongly agree” to (5) “strongly disagree.” I reverse code responses to create approval of premarital sex and approval of casual sex with friends, where higher numbers equate greater approval. Both attitudinal questions were assessed at baseline and then every twelve weeks.

Because desires for sex may be linked to desires for pregnancy, I also include an indicator of whether a respondent wants to get pregnant, coded (0) for “not at all” and (1) for anything else. In only 7% of weeks respondents reported any desire to become pregnant (Table 1). Wants to get pregnant was assessed weekly in the RDSL (Figure 1).

Previous Experiences and Age.

Because the life course perspective suggests women’s sexual behaviors and desire for sex should be influenced by their previous sexual experiences I include a dichotomous indicator of whether respondents’ sexual debut occurred at <=14 years and an indicator of whether respondents have ever had sex, which was assessed at baseline and then updated weekly (Figure 1). I also include respondents’ cumulative number of sex partners, which starts with the baseline number of partners they reported having vaginal intercourse with and is then updated every time they report having vaginal intercourse with a new partner. Finally, I include respondents’ cumulative number of live births. This measure was also assessed at baseline and then updated weekly throughout the RDSL (Figure 1).

Given that cumulative measures may partially capture the effects of time elapsing, I include a continuous measure of age updated weekly (ranging from 18.00 to 22.90 years).

Relationship Context.

All models include two measures of relationship context. The first is relationship status: married, engaged, special, and none or casual.8 None and casual are collapsed into one category because questions about intercourse were only asked to women who reported being in any type of relationship. No relationship is thus perfectly correlated with sexual intercourse. The second is relationship duration, where (0) indicates not in a relationship.

Friends Context.

Two measures of friends’ context are included. Friends’ approval of sex is assessed with the question, “How would your friends react if you had sexual intercourse?” with possible answers ranging from (0) “not at all” to (5) “extremely” positively. Proportion of friends sexually active is assessed with the question, “How many of your friends have had sexual intercourse?” with possible answers ranging from (1) “none” to (5) “almost all.”

Family Context and Race.

Family context is characterized by parents’ approval of sex (measured in the same way as friends’ approval); having a mother <20 at first birth (versus not); mothers’ education, defined as <H.S. completed H.S., and completed secondary; and received public assistance as a child, a dichotomous indicator of childhood disadvantage. Race is captured with a dichotomous indicator of whether a respondent is African American or not.9

Institutional Contexts.

I examine the role of two institutional contexts: school and religion. School was assessed at baseline and then every twelve weeks (Figure 1) and is defined as whether respondents are enrolled in college (2- or 4-year). Religion is operationalized with two measures that were assessed once at baseline (Figure 1). Highly religious is coded (1) for respondents who report that their faith is “very important” or “more important than anything else” and (0) for respondents who report that their faith is “somewhat important” or “not important.” Frequency of religious attendance is an interval-level measure ranging from (0) “never” to (5) “several times a week.” Because 75% of respondents reported a Christian denomination and 20% reported no religion, and thus the primary axis of variation pertained to any/no religion, I do not control for religious affiliation. As a sensitivity test, I interact highly religious and frequency of religious attendance with affiliation and find that the effects of these indicators on desire for sex are not moderated by religion.10

Analytic Strategy

This study is motivated by three questions: How much do young women desire sex? How does this differ across women and change as they progress to adulthood? And, how do women’s sexual and contraceptive behaviors correspond to their underlying desire? To answer the first question, I begin with a descriptive analysis of desire for sex, including an examination of its distribution across women at baseline (at ages 18 and 19) and graphical depictions of how it changes across study participation using Kernel-weighted local polynomial smoothing (focusing on weeks when it was assessed).

Then, to better understand how desire for sex corresponds to different facets of women’s lives and changes with their experiences, I estimate desire for sex using linear regression with random effects.11 This model is also limited to the weeks in which the question was asked.

To address the third question, I begin with a stacked bar chart illustrating how sexual frequency (in terms of weeks) varies with the strength of respondents’ desire for sex. I next estimate intercourse and contraceptive use with a series of logistic regressions with random effects. Because sex and contraceptive use may be jointly determined, these models proceed as follows. First I predict having intercourse in the full sample of study weeks. Given that I expect desire’s effect on sex to be greater amidst hormonal use, I include an interaction between desire for sex and current use of hormonal contraception.12 Following, I estimate hormonal contraceptive use in all study weeks, including a control for whether or not a respondent reported having intercourse that week. Finally, I predict coital contraceptive use limiting the analysis to weeks in which women reported having intercourse. Because the decision to use coital contraception may be partially contingent on whether or not a woman is also using hormonal contraception, these models are stratified by hormonal method use. To verify that the decision to model these outcomes separately does not bias the overall conclusions of this study, I estimate a supplemental multinomial logistic regression in which weekly sexual and contraceptive behaviors are integrated into one dependent measure with four mutually exclusive categories: no intercourse, intercourse with no contraception, intercourse with hormonal (with or without coital), and intercourse with coital only.13 The results of this supplement lead to substantively similar conclusions to those of the primary logistic analysis (Appendix C).

To ensure a correct temporal ordering of events, where desire is modeled subsequent to social ecology, and where sex and contraceptive use are modeled subsequent to social ecology and desire, all time-varying covariates except for age, relationship status, and contemporaneous sexual and contraceptive behaviors are lagged by one week. Relationship status and contemporaneous reproductive behaviors are not lagged because they may be jointly determined with desire and each other. For example, if a respondent is in a special relationship one week and no relationship the next, her relationship status from the prior week should not be relevant to her sexual activity in the current week. As a sensitivity test, I re-estimate all models without lagging any covariates. The results remain nearly identical to those presented below.

Random effects are chosen for the main models because they facilitate the observation of effects of time-invariant measures such as mother’s age at first birth and because they permit the inclusion of individuals for whom the outcome does not vary (such as women who never have intercourse or have intercourse every week). In models with random effects, point estimates of time-invariant predictors reflect between-respondent differences, while time-variant predictors reflect a combination of between- and within-respondent differences. To more explicitly examine the effects of within-woman changes in desire for sex and other time-varying predictors, I rerun all models using person-fixed effects (presented in Appendices A and B). I rely on these supplemental models to adjudicate between differences across women in a given week and changes with women over time when discussing the effects of time-variant predictors.

Results

Variation in Desire for Sex among Young Adult Women

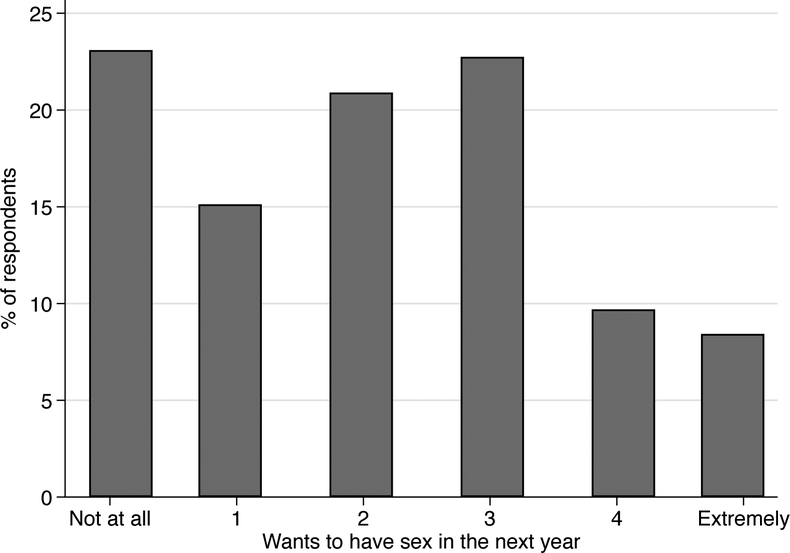

To examine how much young women desire sex and variation in the strength of their desire, I begin with a univariate analysis of how much, at baseline, respondents reported wanting to have sex in the upcoming year (Figure 3). The majority of young women—77%—reported having at least some desire for sex. However, there was substantial heterogeneity in how strong their desire was. While 15% reported low desire (a score of 1), 45% reported a more moderate desire (a score of 2 or 3), and 17% reported a strong or extreme desire for sex in the next year (a score of 4 or 5).

Figure 3:

Distribution of Desire for Sex at Baseline Note: N=925 respondents

During study participation, the average respondent’s desire increased by .88 points from 2.11 at baseline to 2.99 at their last assessment (analysis not shown). The majority of this increase occurred in the first year of participation: by the end of year one, the average respondent’s desire had risen to 2.97—a statistically significant increase from baseline (p<.001, t-tests not shown). Over the course of the second year, mean desire rose only modestly, to 3.19, and by year-end, was not significantly different from mean desire at the end of the first year (t-test not shown). Thus, the average woman’s desire primarily increased in the first year of the study before leveling off. Figure 4 helps visualize this pattern. Comparing trends across differing baseline desire levels in Figure 4 further reveals that women whose desire was the lowest at the start of the study (0–2) experienced the steepest inclines.

Figure 4.

Smoothed Lowess Plots of Desire for Sex over the Course of the Study, Plotted by Level of Desire for Sex at Baseline

Note: N=4,888 weeks when desire was assessed (among 925 respondents)

These descriptive analyses, together, indicate that most women possessed some desire for sex during the study; that the strength of their desire typically grew over time; and that the greatest growth in desire occurred earlier in the study and among women who began with the lowest levels of desire.

How Does the Desire for Sex Vary with Women’s Social Circumstances and Change Over Time?

To assess how young women’s desire varies with their social ecology, I next estimate a linear regression with random effects. The resulting coefficients are plotted in Figure 5 and provided in table format in Appendix A. To ensure that desire is modeled subsequent to ecological factors, all covariates (except for age and relationship status) are lagged by one week. For the sake of parsimony, I do not reiterate this lag when discussing the results below.

Figure 5.

Results of Linear Regression with Random Effects Estimating Desire for Sex in a Given Week

Note: The sample is limited to weeks in which the question about desire for sex was asked (N=4,888 weeks from 925 respondents). Black dots convey point estimates; black lines covey 95% confidence intervals. Corresponding results in table format are provided in Appendix A.

+Measures are lagged to reflect respondents’ situation as of the prior week.

†Measure was assessed once at baseline and therefore does not vary within respondents over time.

Beginning with attitudes and intentions, the results of the random effects model presented in Figure 5 demonstrate that desire for sex increases by .15 units when women report a one-unit increase in approval of premarital sex. It is also .06 units higher among women reporting a one-unit higher approval of casual sex with friends. In addition, desire for sex is positively associated with desire for pregnancy, increasing by .26 points when women report a one-unit increase in wanting to get pregnant.

Continuing with previous experiences and age in Figure 5, desire for sex does not correspond to experiencing sexual debut at <=14 years. However, it does increase by .91 units—half a standard deviation—in the weeks following sexual debut (when women have ever had sex). Desire for sex is also higher among women with a higher cumulative number of sex partners (Figure 5). However, it does not change within women in response to their number of partners (Appendix A). In contrast, desire for sex is lower among women with a higher cumulative number of live births (Figure 5), but again, does not change with having more births (Appendix A). Consistent with Figure 4, desire for sex significantly increases with age.

In terms of friends, family, and relationships, women’s desire for sex increases monotonically with relationship seriousness and is greater when they are in any type of relationship than when they are not. However, it does not change with relationship duration (Figure 5). Desire for sex also increases by .15 when friends’ approval of sex increases by one unit, and by .11 with each increase in proportion of friends who are sexually active. In addition to friends, women’s desire for sex increases by .10 when parents’ approval of sex increases by one unit but does not differ between women whose mother was <20 and women whose mother was older at first birth. Women whose mothers completed college have an average of .32 higher desire than women whose mothers did not complete high school. Consistent with earlier research (Barber, Yarger and Gatny 2015), African American women’s reported desire for sex is an average of .58 points lower than their non-African American peers.

Finally, with respect to institutional contexts, women who are enrolled in college report an average of .16 higher desire for sex than women who are not. Women who are highly religious report an average of .23 lower desire for sex than their peers, though desire for sex does not vary with frequency of religious attendance (Figure 5).

These multivariate results underscore two key points. First, in keeping with the social ecological and life course perspectives, young women’s desire for sex changes with pivotal events like sexual debut and varies with nearly every facet of their social environment. In other words, although highly personal, desire for sex is also highly social. Second, not all ecological factors are equally correlated with desire. Two of the largest positive correlates are relationship status and whether a woman has ever had sex. The magnitudes of associations between desire and these variables are two to fifteen times greater than the magnitude of associations between desire and attitudinal and intentional indicators and four to six times greater than the magnitude of associations between desire and friendship context indicators. These findings suggest that young women’s social ecology may be especially salient to the relational/ social psychological dimension of their sexual desire.

How Are Women’s Sexual Behaviors and Contraceptive Use Related to the Desire for Sex?

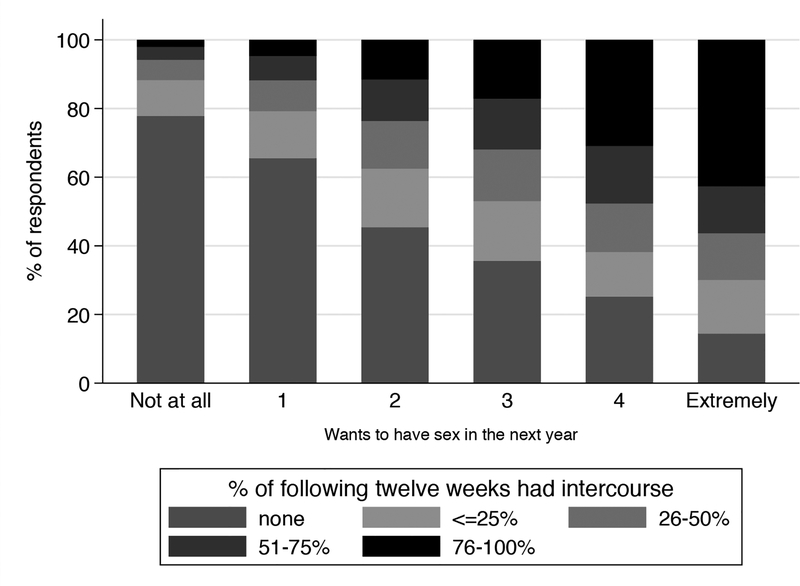

Like many individual-level characteristics, desire for sex may not be a perfect predictor of behavior. Figure 6 portrays the proportion of weeks respondents had intercourse after reporting their desire for sex (which was asked about every twelve weeks). As can be seen in this figure, desire is positively correlated with frequency of intercourse. However, 22% of times when respondents reported not wanting sex at all, they had intercourse in the subsequent twelve weeks. Six percent of times they reported not wanting sex at all they had intercourse in >=50% of the following twelve weeks. At the other end of the spectrum, 15% of times when respondents reported extremely wanting to have sex, they did not have sex at all. Forty-five percent of times they reported extremely wanting sex they had intercourse in <50% of following weeks.

Figure 6:

Percent of Following Twelve Weeks Had Intercourse, by How Much Wanted to Have Sex at Most Recent Assessment

Note: N=54,068 weeks (among 925 respondents). In this figure, frequency of intercourse is measured with respect to twelve week periods because the question “How much do you want to have sex in the next year” was asked every twelve weeks.

Table 2 tests whether the positive, albeit imperfect, relationship between desire for sex and intercourse is robust to the inclusion of covariates, and further tests for variation in this relationship across hormonal contraceptive use. Like the model presented in Figure 5, all time-varying covariates except for age, relationship status, and contemporaneous behaviors are lagged by one-week to ensure that sex is modeled subsequent to women’s desire and social ecology. Again for the sake of parsimony, I do not continue to reference this lag when discussing the results below.

Table 2:

Results from Logistic Regressions with Random Effects Estimating Intercourse and Contraceptive Use in a Given Week

| Irrespective of whether had intercourse: | If had intercourse and. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not use hormonal: | Used hormonal: | |||||||

| Had intercourse | Used hormonal | Used coital (condoms or withdrawal) | Also used coital | |||||

| β | OR | β | OR | β | OR | β | OR | |

| Desire for sex+ | .20 | 1.22 *** | .18 | 1.19 *** | −.09 | .91 * | −.13 | .87 ** |

| (.02) | (.02) | (.05) | (.04) | |||||

| Personal attitudes & intentions+ | ||||||||

| Approval: premarital sex | −.00 | 1.00 | .10 | 1.11 *** | −.02 | .98 | .06 | 1.07 |

| (.02) | (.02) | (.06) | (.06) | |||||

| Approval: sex with friends | .04 | 1.04 | .07 | 1.07 ** | −.20 | 82 *** | −.11 | .89 * |

| (.02) | (.02) | (.06) | (.05) | |||||

| Wants to get pregnant | .75 | 2.11 *** | −.67 | .51 *** | −1.69 | .18 *** | −.20 | .82 |

| (.08) | (.09) | (.13) | (.23) | |||||

| Previous experiences+ & age | ||||||||

| Sexual debut <=14 years† | .39 | 1.47 * | .11 | 1.12 | −1.34 | .26 *** | −.81 | .44 |

| (.20) | (.37) | (.38) | (.43) | |||||

| Cum. no. sex partners | .12 | 1.12 *** | .03 | 1.03 * | −.04 | .96 | −.02 | .99 |

| (.01) | (.01) | (.02) | (.03) | |||||

| Cumulative no. live births | −.60 | .55 *** | .95 | 2.59 *** | .75 | 2.11 *** | .79 | 2.19 ** |

| (.09) | (.11) | (.18) | (.25) | |||||

| Age | −.19 | .83 *** | −.41 | .66 *** | −.37 | .69 *** | −.52 | .59 *** |

| (.03) | (.03) | (.08) | (.07) | |||||

| Current relationship | ||||||||

| Status (ref: none) | ||||||||

| Married | 3.39 | 29.74 *** | .20 | 1.22 | −2.10 | .12 *** | −1.59 | .20 *** |

| (.13) | (.15) | (.32) | (.41) | |||||

| Engaged | 3.34 | 28.24 *** | .50 | 1.66 *** | −.96 | .38 *** | −1.28 | .28 *** |

| (.09) | (.10) | (.23) | (.27) | |||||

| Special | 3.19 | 24.39 *** | .33 | 1.39 *** | −.36 | .70 | −.87 | 42 *** |

| (.05) | (.06) | (.19) | (.19) | |||||

| Relationship duration | .01 | 1.01 *** | .00 | 1.00 * | −.00 | 1.00 | −.01 | .99 ** |

| (.00) | (.00) | (.00) | (.00) | |||||

| Friend context+ | ||||||||

| Friends’ approval of sex | .15 | 1.17 *** | .08 | 1.08 *** | .02 | 1.02 | .00 | 1.00 |

| (.02) | (.02) | (.04) | (.06) | |||||

| Prop. friends sex. active | .14 | 1.15 *** | .22 | 1.24 *** | −.02 | .98 | −.29 | .75 *** |

| (.03) | (.03) | (.07) | (.07) | |||||

| Family context+ & race | ||||||||

| Parents’ approval of sex | .07 | 1.08 *** | .06 | 1.06 ** | −.21 | .81 *** | −.02 | .98 |

| (.02) | (.02) | (.04) | (.05) | |||||

| Mother <20 at first birth† | .36 | 1.43 * | .19 | 1.20 | .15 | 1.16 | .06 | 1.06 |

| (.15) | (.29) | (.30) | (.35) | |||||

| Mother’s education (ref: <H.S.) † | ||||||||

| Completed H.S. | −.40 | .67 | .44 | 1.55 | .33 | 1.40 | −.05 | .95 |

| (.25) | (.47) | (.47) | (.60) | |||||

| Completed college | −.83 | .44 ** | 1.04 | 2.84 | 1.54 | 4.68 ** | .48 | 1.62 |

| (.29) | (.53) | (.58) | (.67) | |||||

| Received public assistance as child† | .11 | 1.11 | −.59 | .56 * | −.55 | .58 | .12 | 1.13 |

| (.15) | (.28) | (.30) | (.35) | |||||

| African American† | −.20 | .82 | −.29 | .75 | .21 | 1.24 | .19 | 1.20 |

| (.17) | (.32) | (.36) | (.42) | |||||

| Institutional contexts+ | ||||||||

| School | ||||||||

| Enrolled in college | −.14 | .87 ** | .26 | 1.30 *** | .08 | 1.08 | .14 | 1.15 |

| (.05) | (.06) | (.13) | (.14) | |||||

| Religion | ||||||||

| Highly religious† | −.08 | .92 | −.32 | .73 | −.64 | .53 | .02 | 1.02 |

| (.16) | (.31) | (.33) | (.36) | |||||

| Frequency of religious attendance† | −.08 | .93 | −.20 | .82 * | .07 | 1.07 | .14 | 1.15 |

| (.05) | (.09) | (.10) | (.12) | |||||

| Current contraceptive behavior | ||||||||

| Used hormonal contra. this week | .67 | 1.96 *** | -- | -- | -- | |||

| (.10) | -- | -- | -- | |||||

| Desire for sex+ * Used hormonal | .07 | 1.07 ** | -- | -- | -- | |||

| (.02) | -- | -- | -- | |||||

| Current sexual behavior | ||||||||

| Had intercourse this week | .84 | 2.32 *** | -- | -- | ||||

| (.04) | -- | -- | ||||||

| Constant | −1.53 | .22 ** | 3.25 | *** | 12.26 | *** | 12.48 | |

| (.59) | (.78) | (1.66) | (1.57) | |||||

| Observations (weeks) | 53,713 | 53,713 | 8,979 | 8,514 | ||||

| Number of respondents | 925 | 925 | 623 | 498 | ||||

| Reference category | Did not have intercourse | Did not use hormonal | Did not use any method | Used hormonal but not coital | ||||

Note: In the first two models, the sample is comprised of all respondents’ study weeks. In the third model, the sample is comprised of respondents’ study weeks what they had intercourse and did not use hormonal contraception. In the last model, the sample is comprised of respondents’ study weeks when they had intercourse and used hormonal contraception. The number of respondents (and corresponding weeks) is not uniform across models because some respondents switched methods during the study. These respondents appear in multiple models.

Standard errors in parentheses,

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05

Measures are lagged and reflect respondents’ situation as of the prior week.

Measure was assessed once at baseline and therefore does not vary within respondents over time.

The results of the first model in Table 2 indicate that respondents’ odds of having intercourse increase with the strength of their desire for sex and that this increase is greater when women are using hormonal contraception than when they are not. Because interaction effects are notoriously difficult to interpret in non-linear models (Ai and Norton 2003), Figure 7 transforms these results into marginal effects holding all covariates at their mean. As can be seen in this figure, when the average respondent is not using hormonal contraception a one-unit increase in her desire is associated with a 2-percentage point increase in her probability of having intercourse that week. When using hormonal contraception, a one-unit increase in her desire is associated with a 4-percentage point increase in her probability of intercourse (Figure 7). Considering that half of respondents reported an increase of 2 or more units in desire for sex over the course of the study and 35% reported an increase of 3 or more units (analysis not shown), these effect sizes are non-trivial.

Figure 7.

Estimated Change in the Probability of Intercourse and Contraceptive Use Associated with a 1-Unit Increase in Desire for Sex

Note: Marginal effects are calculated from the results of logistic regressions with random effects presented in Table 2, holding all covariates at their mean.

A related question is whether young women’s contraceptive use also varies with desire for sex. This is also explored in Table 2. If having stronger desire for sex affects a woman’s plans or expectations to have sex, as cognitive science indicates, then it should result in deliberate contraceptive planning. To test this, I run a logistic regression estimating hormonal contraceptive use in a given week, controlling for whether or not respondents have intercourse that same week. As anticipated, the results suggest that a young woman’s odds of using hormonal contraception increase by 19% for every one-unit increase in desire for sex. To determine whether desire for sex is also related to a situational behavior that requires self-control, I run logistic regressions estimating coital contraceptive use in weeks when respondents have intercourse. Again the results confirm the anticipated pattern—in weeks when women are having sex and not using a hormonal method, a one-unit increase in desire for sex is associated with a 9% decrease in the odds of using coital contraception (Table 2). In weeks when they are having sex and using a hormonal method, desire for sex is associated with a 13% reduction in these odds (Table 2). Comparing across coefficients in Table 2 suggests that the magnitude of associations between desire and contraceptive use—both hormonal and coital—are sizable: they are approximately equivalent to or larger than the size of associations these outcomes share with sexual attitudes, the perceived attitudes of friends and family, and educational environment.

Figure 7 consolidates the results of different models, and for the sake of clarity, conveys them in terms of desire’s marginal effects on behavioral outcomes (holding all covariates at their mean). Two clear patterns emerge from this figure. First, stronger desire for sex is associated with a higher probability that women will have sex, especially when they’re using hormonal contraception. Moreover, stronger desire for sex is associated with a higher likelihood of hormonal contraceptive use itself. Taken together, these findings suggest that desire may influence sexual forethought and planning. Second, although desire is positively associated with hormonal use, it is negatively associated with coital use, including when women are not using a hormonal method. This latter finding suggests that desire may operate differently in the heat of the moment, resulting in situational decisions in which women prioritize immediate pleasure or satisfaction over concerns about longer-term, unintended consequences of (unprotected) sex.

Sensitivity Analysis: Bias Arising from Sexual Orientation

The preceding analysis relies on a diverse sample of women, some of whom may not identify as hetero- or bisexual. The inclusion of these women may attenuate regression results because desire for sex is measured in the RDSL with regard to vaginal intercourse. A one-time supplement in the RDSL, completed by 590 women, asked respondents to choose which of the following “best fits how [they] think about [themselves]: “lesbian, gay, or queer,” “bisexual,” “straight,” or “I don’t label myself in this way.” During this supplement 82% of respondents reported identifying as “straight” (e.g. heterosexual, n=485); 6% as bisexual (n=35). To test whether the inclusion of non-hetero or bisexual respondents biases the primary results, I rerun all analyses, limiting the sample to women who reported thinking of themselves as hetero- or bisexual. The results, presented in Appendices D and E remain nearly identical in terms of magnitude, direction, and significance, suggesting that the inclusion of women from different sexual orientations does not bias the overall conclusions of this study. This is not surprising given that the majority (88%) of respondents who provided information on their sexual orientation identified as hetero- or bisexual.

Discussion

This study offers one of the first sociological investigations into young women’s sexual desire, including its social production and salience for sexual and reproductive decision-making during the transition to adulthood. The findings offer three clear takeaways. First, despite sexual double standards (Fjær, Pedersen and Sandberg 2015; Kreager and Staff 2009), sexual desire is highly prevalent among young women: 77% of respondents reported at least some desire at baseline and the strength of their desire typically increased over time. Increases in desire were steepest in the first year of the study and then stabilized, suggesting that the average young woman not only develops stronger desire as she matures, but that she may become better at recognizing and acknowledging the strength of her desire as she and her peers acquire more sexual experience. Relatedly, women who started the study with the least desire exhibited the steepest inclines, likely owing to the large positive correlation between sexual debut and desire: those with little desire were the least sexually experienced at baseline; once they debuted, their desire increased dramatically.

Second, beyond temporal variation, desire for sex varies across context—a finding consistent with social ecological and life course perspectives. It was stronger among women who perceived sex to be normative among their friends and family and among women who were enrolled in college (an often sexually permissive environment (Bearak 2014)). It also evolved alongside women’s personal circumstances, such as their relationship seriousness. Thus, although typically conceived of as highly personal and biological, desire for sex is also highly social. Not all ecological and life course indicators were equally associated with desire, however. The largest predictors were history of intercourse and relationship seriousness, both of which theoretically correspond to the social psychological dimension of desire (a yearning for pleasure, intimacy, and satisfaction (Levine 2003)). By contrast, family, friend, and institutional contexts, which theoretically correspond to the sociocultural dimension (the valuation of sexual expression), were more modest predictors. Thus, how much young women wanted to have sex was more sensitive to ecological factors appealing to the social psychological, relational aspect of desire.

Third, net of ecological factors, sexual desire was highly predictive of women’s sexual and reproductive behavior. For example, women were more likely to have sex when they more strongly desired it. This finding qualifies recent research on women’s (lack of) sexual agency. For instance, although several studies suggest that young women are less likely to have an orgasm than young men during sexual encounters (Armstrong, England and Fogarty 2012), and that many young women have difficulty negotiating cunnilingus (Backstrom, Armstrong and Puentes 2012), this study indicates that women are nonetheless more likely to have sex when they want it. If sexual encounters are comprised of two steps—the pursuit of partners to have sex with and the negotiation of specific sexual acts with those partners—then this study’s findings suggest that women are generally successful at the former, despite not necessarily being as successful at the latter. This is not necessarily surprising given that women sometimes desire sex for reasons unrelated to physical pleasure. One reason is that sex has become normative and/or expected among many young adults despite sexual double standards (Fjær, Pedersen and Sandberg 2015; Tolman and McClelland 2011). Here, social motivations for sex can be seen in the positive association between desire for sex and the proportion of friends a woman believes to be sexually active. Another non-physical reason for desiring sex is the role that sex plays in fostering intimacy and stability in romantic relationships (Levine 2003), which is consistent with the finding that women report stronger desires for sex when they are in more serious relationships.

Like their sexual activity, women’s contraceptive use varies with desire. That is, how much young women want to have sex is positively associated with using hormonal contraception and negatively associated with using a coital method (Figure 7). Although I am unable to examine cognition directly, these findings suggest that desire is related to both deliberate and situational sexual decision-making. Such an interpretation aligns with cognitive research, which suggests that people possess two cognitive systems—one deliberate and one automatic—that may be affected differently by a woman’s desire (Kahneman 2011; Kőszegi and Rabin 2006; Slovic et al. 2007). That is, because desire should result in sexual forethought—the expectation or hope of sex—it should inspire the use of hormonal contraception in advance of sex (assuming most young women do not want to get pregnant). This interpretation is supported by the fact that associations between desire and intercourse are larger when women are using a hormonal method than when they are not. At the same time, because stronger desire indicates more positive affect toward sex, which in turn biases women’s intuition (Slovic et al. 2007), and because intuition forms the basis of automatic decision-making (Kahneman 2011), desire should impede the use of situational, coital methods that are sometimes viewed as an impediment to pleasure and intimacy (Higgins and Hirsch 2008) and that need to be enacted in the moment.

Notably, a supplemental analysis using person-fixed effects confirmed that women’s behavior changes with the strength of their desire. In other words, rather than simply accounting for behavioral differences across women, desire for sex is closely related to increases in sexual activity and hormonal contraceptive use, and to decreases in condom use and withdrawal within women as they progress through the transition to adulthood. Moreover, the magnitudes of these associations are comparable in size or larger than associations with sexual attitudes and perceived norms among family and friends. These sizable associations of desire for sex net of ecological factors, and the fact that these associations depict behavioral change, underscore the critical value of accounting for women’s desire when examining their sexual and reproductive behavior.

Despite its contributions, this study faces several limitations. First, RDSL data provide information solely on young women. Thus, I am unable to determine gender-based differences in the ecological and behavioral correlates of desire for sex. Nor am I able to assess the extent to which men’s desire moderates the effects of women’s desire on their own behavior. Given the age of the sample, I am also unable to make inferences about women of older ages. Considering changes in women’s relationships, resources, and priorities over time, women’s valuation of sexual expression and their social psychological motivations for sex are likely to change as they grow older. While this study cannot explore such a possibility, it nonetheless raises new questions about how and why women’s sexual desire evolves as they age and the potential (in)constancy of its behavioral associations across the life course.

A second limitation is that desire for sex was only asked about with regard to heterosexual intercourse. This leaves open the possibility that desire for other sex acts operates differently than found here. A robustness check did however confirm that the inclusion of homosexual women does not bias estimated relationships between social ecology and desire or between desire and behavior. Another limitation is that the primary measure of desire for sex was only assessed with one question and asked about with respect to wanting sex in the next year. It is therefore not possible for this study to distinguish between the different dimensions of desire for sex (e.g. sociocultural values, social psychological motivation, and hormonal) or between acute and longer-term desires. Nevertheless, a supplemental analysis revealed that the measure used in this study is correlated with a number of items related to sexual appetite, suggesting that it at least partially reflects acute desires despite being asked about with respect to a larger time horizon. Finally, desire for sex was asked about every twelve weeks, whereas sex and contraceptive use were assessed weekly. It is therefore possible that women’s desire fluctuated in between when it was asked, potentially leading me to underestimate the strength of relationships between desire and behavior in multivariate analyses and to overestimate the mismatch between desire for sex and sexual activity in bivariate analyses.

Mismatches between desires and behavior were nevertheless too common to entirely be an artifact of measurement error. Their widespread prevalence raises important new questions about how and why this misalignment arises. More than one-fifth of times when respondents said they did not want to have sex at all in the upcoming year they had intercourse in the following 12 weeks. Pressure and coercion from partners may explain at least some of these instances (Impett and Peplau 2003). Strong desires for sex were also inconsistently met: nearly half of times when respondents reported that they extremely wanted to have sex, they only had sex in half of the following weeks. Though it is again possible that at least some women changed their minds during the twelve-week period, a related possibility is that once desires are temporarily sated women stop pursuing sex, at least in the short term. Alternatively, women may not always be able to find willing sexual partners. A third possibility is that unobserved circumstances such as sharing a dorm room or living with one’s parents may thwart women’s ability to regularly have sex. These circumstances may not only moderate the association between desire and sexual behavior but also its associations with contraceptive use.

Taken together, this study’s findings demonstrate the immense value of expanding scholarly understandings of young women’s sexual desire. Doing so not only opens up exciting questions about women’s sexual agency, but also expands scholarly conceptualizations of sexual desire as a social rather than exclusively personal or biological phenomenon. Moreover, investigating the relationship between women’s sexual desire and behavior reorients social scientific approaches to sexual and reproductive decision-making by shifting attention to women’s motivations to have sex rather than to avoid it.

Appendix A: Results from Linear Regressions Estimating Desire for Sex in a Given Week

| Random effects | Fixed effects | |

|---|---|---|

| β | β | |

| Personal attitudes & intentions+ | ||

| Approval: premarital sex | .15 *** | .12 *** |

| (.02) | (.02) | |

| Approval: sex with friends | .06 ** | .02 |

| (.02) | (.02) | |

| Wants to get pregnant | .26 ** | .22 * |

| (.08) | (.09) | |

| Previous experiences+ and age | ||

| Sexual debut <=14 years† | .10 | -- |

| (.10) | -- | |

| Ever had sex | .91 *** | .92 *** |

| (.07) | (.09) | |

| Cumulative no. sex partners | .03 *** | .01 |

| (.01) | (.01) | |

| Cumulative no. births | −.24 *** | −.05 |

| (.07) | (.13) | |

| Age | .22 *** | .27 *** |

| (.02) | (.03) | |

| Current relationship | ||

| Status (ref: none) | ||

| Married | .92 *** | .77 *** |

| (.14) | (.16) | |

| Engaged | .73 *** | .64 *** |

| (.08) | (.09) | |

| Special | .47 *** | .44 *** |

| (.04) | (.05) | |

| Relationship duration | .00 | −.00 |

| (.00) | (.00) | |

| Friends context+ | ||

| Friends’ approval of sex | .15 *** | .12 *** |

| (.02) | (.02) | |

| Prop. friends sexually active | .11 *** | .06 * |

| (.02) | (.02) | |

| Family context+ and race | ||

| Parents’ approval of sex | .10 *** | .11 *** |

| (.02) | (.02) | |

| Mother <20 at first birth† | −.09 | -- |

| (.08) | -- | |

| Mother’s education (ref: <H.S.) † | -- | |

| Completed H.S. | .08 | -- |

| (.13) | -- | |

| Completed college | .32 * | -- |

| (.15) | -- | |

| Received public assistance as a child† | −.08 | -- |

| (.08) | -- | |

| African American† | −.58 *** | -- |

| (.09) | -- | |

| Institutional contexts+ | ||

| School | ||

| Enrolled in college | .16 *** | .10 |

| (.05) | (.05) | |

| Religion | ||

| Highly religious† | −.23 ** | -- |

| (.08) | -- | |

| Frequency of religious attendance† | −.00 | -- |

| (.02) | -- | |

| Constant | −4.37 *** | −4.97 *** |

| (.42) | (0.50) | |

| Observations (weeks) | 4,888 | 4,888 |

| Number of respondents | 925 | 925 |

Note: The sample is limited to weeks in which the question about desire for sex was asked.

Standard errors in parentheses,

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05

Measures are lagged and reflect respondents’ situation as of the prior week.

Measure was assessed once at baseline and therefore does not vary within respondents over time.

Appendix B: Results from Logistic Regressions with Fixed Effects Estimating Intercourse and Contraceptive Use in a Given Week

| Irrespective of whether had intercourse: | If had intercourse and… | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not used hormonal: | Used hormonal: | |||||||

| Had intercourse | Used hormonal | Used coital (condoms or withdrawal) | Also used coital | |||||

| β | OR | β | OR | β | OR | β | OR | |

| Desire for sex+ | .16 | 1.18 *** | .17 | 1.18 *** | −.13 | .87 ** | −.10 | .91 * |

| (.02) | (.02) | (.05) | (.05) | |||||

| Personal attitudes & intentions+ | ||||||||

| Approval: premarital sex | −.01 | .99 | .10 | 1.10 *** | −.07 | .94 | .05 | 1.05 |

| (.02) | (.02) | (.06) | (.06) | |||||

| Approval: sex w. friends | .03 | 1.03 | .07 | 1.07 ** | −.20 | .82 *** | −.11 | .90 * |

| (.02) | (.02) | (.06) | (.05) | |||||

| Wants to get pregnant | .67 | 1.96 *** | −.59 | .55 *** | −1.34 | .26 *** | .10 | 1.11 |

| (.08) | (.09) | (.13) | (.23) | |||||

| Previous experiences+ & age | ||||||||

| Cum. no. sex partners | .12 | 1.13 *** | .00 | 1.00 | .02 | 1.02 | .00 | 1.00 |

| (.01) | (.04) | (.04) | (.04) | |||||

| Cumulative no. live births | −1.15 | .32 *** | 1.53 | 4.60 *** | 1.79 | 5.97 *** | 1.53 | 4.60 *** |

| (.11) | (.22) | (.41) | (.22) | |||||

| Age | −.11 | .90 *** | −.58 | .56 *** | −.62 | .54 *** | −.58 | .56 *** |

| (.03) | (.11) | (.09) | (.11) | |||||

| Current relationship | ||||||||

| Status (ref: none) | ||||||||

| Married | 3.28 | 26.57 *** | .20 | 1.23 | −1.91 | .15 *** | −2.18 | .11 *** |

| (.13) | (.15) | (.34) | (.51) | |||||

| Engaged | 3.14 | 23.22 *** | .51 | 1.66 *** | −.80 | .45 *** | −1.51 | .22 *** |

| (.09) | (.10) | (.24) | (.30) | |||||

| Special | 3.04 | 21.00 *** | .32 | 1.38 *** | −.38 | .68 * | −.87 | .42 *** |

| (.05) | (.06) | (.19) | (.19) | |||||

| Relationship duration | .00 | 1.00 | .00 | 1.00 | −.00 | 1.00 | −.01 | .99 |

| (.00) | (.00) | (.01) | (.01) | |||||

| Friend context+ | ||||||||

| Friends’ approval of sex | .15 | 1.16 *** | .07 | 1.08 *** | .02 | 1.02 | .03 | 1.03 |

| (.02) | (.02) | (.05) | (.06) | |||||

| Prop. friends sex. active | .08 | 1.08 ** | .21 | 1.23 *** | .04 | 1.04 | −.32 | .73 *** |

| (.03) | (.03) | (.08) | (.08) | |||||

| Family context+ & race | ||||||||

| Parents’ approval of sex | .07 | 1.07 *** | .06 | 1.06 ** | −.21 | .81 *** | −.03 | .97 |

| (.02) | (.02) | (.05) | (.05) | |||||

| Institutional contexts+ | ||||||||

| School | ||||||||

| Enrolled in college | −.07 | .93 | .24 | 1.26 *** | .05 | 1.05 | .16 | 1.17 |

| (.05) | (.06) | (.14) | (.14) | |||||

| Current contraceptive behavior | ||||||||

| Used hormonal contra. this week | .59 | 1.80 *** | -- | -- | -- | |||

| (.10) | -- | -- | -- | |||||

| Desire for sex+ * Used hormonal | .09 | 1.09 *** | -- | -- | -- | |||

| (.03) | -- | -- | -- | |||||

| Current sexual behavior | ||||||||

| Had intercourse this week | -- | .82 | 2.27 *** | -- | -- | |||

| -- | (.04) | -- | -- | |||||

| Observations (weeks) | 39,723 | 33,125 | 5,321 | 6,168 | ||||

| Number of respondents | 679 | 537 | 244 | 244 | ||||

| Reference category | Did not have intercourse | Did not use hormonal | Did not use any method | Used hormonal but not coital | ||||

Note: In the first two models, the sample is comprised of all respondents’ study weeks. In the third model, the sample is comprised of respondents’ study weeks what they had intercourse and did not use hormonal contraception. In the last model, the sample is comprised of respondents’ study weeks when they had intercourse and used hormonal contraception. The number of respondents (and corresponding weeks) is not uniform across models because some respondents switched methods during the study. These respondents appear in multiple models.

Standard errors in parentheses,

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05

Measures are lagged and reflect respondents’ situation as of the prior week.

Appendix C: Multinomial Logistic Regression Estimating Joint Selection into Intercourse and Contraceptive Use in a Given Week, Rotating Reference Category

| No intercourse | Intercourse, no contraception | Intercourse with hormonal | Intercourse with coital only | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | OR | β | OR | β | OR | β | OR | |

| Ref: no intercourse | ||||||||

| Desire for sex+ | -- | .34 | 1.40 *** | .36 | 1.43 *** | .25 | 1.29 *** | |

| -- | (.07) | (.09) | (.04) | (.06) | (.03) | (.04) | ||

| Constant | -- | −4.92 | .01 * | −1.61 | .20 | −2.59 | .07 * | |

| -- | (2.04) | (.01) | (1.39) | (.28) | (1.25) | (.09) | ||

| Ref: intercourse, no contraception | ||||||||

| Desire for sex+ | −.34 | .71 *** | -- | .02 | 1.02 | −.08 | .92 | |

| (.07) | (.05) | -- | (.07) | (.07) | (.06) | (.06) | ||

| Constant | 4.92 | 136.52 * | -- | 3.30 | 27.19 | 2.32 | 10.20 | |

| (2.04) | (278.40) | -- | (2.25) | (61.24) | (2.15) | (21.96) | ||

| Ref: intercourse with hormonal | ||||||||

| Desire for sex+ | −.36 | .70 *** | −.02 | .98 | -- | −.10 | .90 * | |

| (.04) | (.03) | (.07) | (.07) | -- | (.04) | (.04) | ||

| Constant | 1.61 | 5.02 | −3.30 | .04 | -- | −.98 | .38 | |

| (1.39) | (7.00) | (2.25) | (.08) | (1.64) | (.61) | |||

Note: In all models, the sample is comprised of all of respondents’ study weeks (N=54,068 weeks among 925 respondents). The reference category of the dependent variable is denoted with --. All models adjust for the same controls as in Table 2 (except for current sexual and contraceptive behavior which are captured in the dependent variable).

Standard errors, clustered by respondent, in parentheses,

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05

Measures are lagged and reflect respondents’ situation as of the prior week.

Appendix D: Results from Linear Regression with Random Effects Estimating Desire for Sex in a Given Week, Limited to Hetero- and Bisexual Respondents

| β | |

|---|---|

| Personal attitudes & intentions+ | |

| Approval: premarital sex | .16 *** |

| (.02) | |

| Approval: sex with friends | .05 * |

| (.02) | |

| Wants to get pregnant | .31 *** |

| (.09) | |

| Previous experiences+ and age | |

| Sexual debut <=14 years† | .15 |

| (.14) | |

| Ever had sex | .97 *** |

| (.08) | |

| Cumulative no. sex partners | .03 ** |

| (.01) | |

| Cumulative no. births | −.15 |

| (.09) | |

| Age | .21 *** |

| (.02) | |

| Current relationship | |

| Status (ref: none) | |

| Married | .83 *** |

| (.16) | |

| Engaged | .67 *** |

| (.10) | |

| Special | .44 *** |

| (.05) | |

| Relationship duration | .00 |

| (.00) | |

| Friends context+ | |

| Friends’ approval of sex | .15 *** |

| (.02) | |

| Prop. friends sexually active | .10 *** |

| (.02) | |

| Family context+ and race | |

| Parents’ approval of sex | .13 *** |

| (.02) | |

| Mother <20 at first birth† | −.13 |

| (.10) | |

| Mother’s education (ref: <H.S.) † | |

| Completed H.S. | .30 |

| (.17) | |

| Completed college | .44 * |

| (.19) | |

| Received public assistance as a child† | −.05 |

| (.10) | |

| African American† | −.58 *** |

| (.11) | |

| Institutional contexts+ | |

| School | |

| Enrolled in college | .18 ** |

| (.06) | |