ABSTRACT

Glutaric aciduria type 1 (GA1) is caused by a deficiency of the enzyme glutaryl CoA dehydrogenase. It generally presents with developmental delay, dystonia, and large head. We are reporting siblings of GA1, presenting with an atypical phenotype with novel pathogenic variant. Thirteen-year-old boy presented with global developmental delay and stiffness of limbs. Examination revealed normocephaly and generalized dystonia. MRI T2WI was suggestive of symmetrical posterior putaminal atrophy. Tandem mass spectroscopy (TMS) and urinary gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GCMS) were normal. Genetic analysis revealed a novel pathogenic homozygous missense variant in GCDH gene. An 8-year-old girl younger sibling of above child also had developmental delay and dystonia, posterior putamen atrophy in the MRI of brain, and same pathogenic variant in GCDH gene. Parents screening showed heterozygous status in both parents of same pathogenic variant. Any child who presents with global developmental delay with dystonia even with normocephaly, isolated symmetrical posterior putamen changes, with normal TMS and GCMS, a possibility of glutaric aciduria type 1 has to be considered.

KEYWORDS: GCDH gene, global developmental delay, glutaryl CoA dehydrogenase, normocephaly

INTRODUCTION

Glutaric aciduria type 1 (GA1) is an inborn error of metabolism involving lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan metabolism caused by the deficiency of enzyme glutaryl CoA dehydrogenase enzyme.[1] They commonly present with developmental delay/regression, dystonia, and involuntary movements with large head. Neuro-radiologically, they are characterized by wide sylvian fissure secondary to bilateral frontotemporal atrophy (Bat wing sign) with subdural hygromas along with caudate and putamen involvement.[2,3] Here we report GA1 in siblings, with an atypical presentation.

CASE

Case 1

Thirteen-year-old boy born to consanguineous marriage presented with global developmental delay with stiffness of limbs. Birth history was uneventful. Global developmental delay was present, especially in motor domain. Currently, the child can walk with support, he can speak in sentences, replies to simple questions, and can tell stories with meaning. At present, he can identify numbers but he is unable to perform simple calculations and he does not know exact money concept. He has attained toilet training both during day and night in the last 6 years of life. On examination, the child was alert, conversing, and responding well to simple questions. Head circumference was 47cm (microcephaly). Neurologically, child had dystonia [Figure 1] of all limbs, with exaggerated deep tendon reflexes and extensor plantar.

Figure 1.

Clinical photograph of siblings showing dystonia (white arrows in A) in the resting state and increased dystonia when extending the limbs (white arrows1B)

Case 2

Eight-year-old girl who is the younger sibling of case 1, presented with complaints of global developmental delay. Birth history was uneventful and there was predominant motor delay. Currently, she can speak in sentences, replies to questions, and can tell stories with meaning. At present, she can perform simple calculations but unaware of exact money concept. She has attained toilet training both during day and night by 5 years of life. On examination, she was alert and responding to questions appropriately. Head circumference was 46.5cm (microcephaly). Neurological examination revealed dystonic posturing [Figure 1] with exaggerated deep tendon reflexes and extensor plantar.

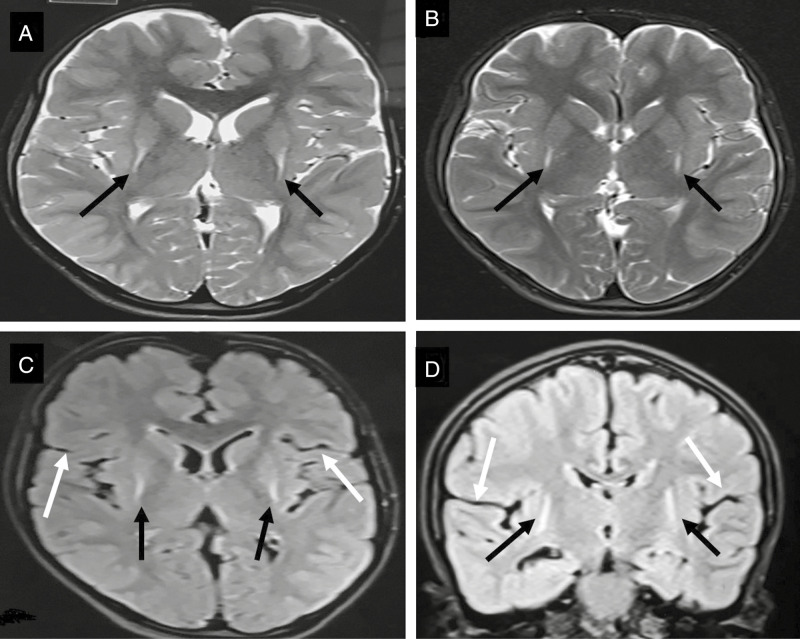

On investigations, complete hemogram, renal function, liver function, arterial blood gas, serum ammonia, and serum lactate were normal. MRI brain in both children showed T2 hyperintensities in posterior putamen with volume loss [Figure 2A and B]. Tandem mass spectrometry (TMS) and urinary gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GCMS) which were repeated twice were normal. Genetic analysis showed a novel homozygous missense substitution p.Ala169Thr mutation in GCDH gene. Testing for same gene in younger sibling showed homozygous state and both parents showed heterozgyous status. Both these children are being treated with trihexyphenidyl for dystonia and they are on special diet along with carnitine and riboflavin supplementation with sick day advice and they are on regular neurodevelopmental follow up with significant improvement noted during follow up in both siblings.

Figure 2.

MRI T2 axial of case 1 (A) and case 2 (B) showing bilateral symmetrical hyperintensities in posterior putamen with posterior putaminal atrophy (black arrows). Axial FLAIR (C) and coronal FLAIR (D) no widening of sylvian fissure and no frontotemporal lobe atrophy that is usual finding in glutaric aciduria as shown in [Figure 3]

DISCUSSION

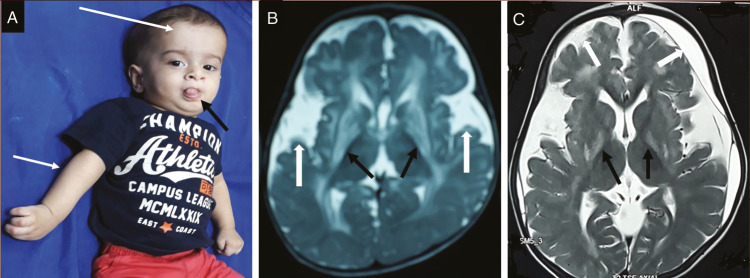

In this case report, we describe two genetically confirmed cases of GA1 in Indian siblings with a novel pathogenic variant who presented with developmental delay, abnormal movements in the form of dystonia in the absence of classical macrocephaly and wide sylvian fissure with frontotemporal atrophy on MRI brain with normal TMS and urinary GCMS. Both these children had microcephaly, isolated posterior putamen involvement in MRI brain and had normal urinary GCMS and TMS which is not a typical feature of this disorder. In literature, microcephaly has been rarely reported in GA1. Microcephaly reported by Sharawat et al.[4] in GA1 attributed it to hypoxic brain injury and severe cerebral atrophy. Muranjan et al.[5] published a series of four cases of GA1 among which three had microcephaly. However, in these cases, there was no cerebral atrophy or hypoxic injury. In classical glutaric aciduria large head, protrusion of tongue due to lingual dystonia, and right upper limb dystonia as shown in Figure 3A are common features.

Figure 3.

Infant with classical glutaric aciduria. (A) clinical photo showing large head (large arrow), protrusion of tongue due to lingual dystonia (small black arrow), dystonia of right upper limb (small white arrow), (B) MRI of same child, axial T2WI showing bilateral basal ganglionic (black arrows) and periventricular hyperintensities with widening of bilateral sylvian fissures (white arrows), and (C) MRI of different child, axial T2WI showing hyperintensities involving bilateral globus pallidi (black arrows), periventricular white matter, widening of bilateral sylvian fissure and subdural collections (white arrows)

Neuroradiologically, the most characteristic finding of GA1 is the presence of very wide CSF spaces and open sylvian fissure [Figure 3B and C], namely the bat wing sign,[3] signal changes in the basal ganglia [Figure 3B and C], and subdural collections [Figure 3C]. Acute striatal necrosis can be visualized as focal, usually symmetric, stroke-like signal hyperintensities on T2 and DWI MRI.[6] Over a period of weeks, circumscribed and near-complete degeneration of putamina occurs with variable extension to caudate and pallidi. Neural tissue is replaced by irreversible thin gliotic scar resulting in dystonia which is irreversible, static and severe.[7] Similar findings were seen in our children except only isolated symmetrical involvement of bilateral posterior putamen and there was absence of batwing sign which is a classical finding and was observed in all eleven cases in a case series of GA1 reported by Kamte et al.[8]

Both our children had normal TMS and normal urinary GCMS and diagnosis was confirmed by genetic study. This is possibly due to the extremely low excretor biochemical phenotype of GA1. Various low excretor biochemical phenotypes of GA1 and its associated mutations in the GCDH gene have been reported.[9] The mutation identified in our siblings is a novel variant. The identified homozygous missense substitution p.Ala169Thr alters a conserved residue in protein. The in-splice prediction tools (SOFT, LRT, mutation taster, polyphen-2, FATHMM) predict the variant as damaging to protein. The identified variant is a novel variant which has not reported in literature so far and this could possibly be the reason of the unusual clinical, biochemical, and radiological findings observed in these siblings.

The unusual features observed in these siblings with identified novel variant in GCDH gene are microcephaly, normal TMS, normal urinary GCMS, isolated posterior putamen involvement in the absence of bat wing sign. This case report highlights the importance of genotype-phenotype correlation and the importance of genetic testing in the identification of neurometabolic disorders with normal biochemical evaluation especially in the presence of atypical phenotypes.

CONCLUSION

Any child who presents with global developmental delay with dystonia, even with normocephaly with isolated symmetrical posterior putamen changes, with normal metabolic screening, a possibility of glutaric aciduria type-1has to be considered.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodman SI, Markey SP, Moe PG, Miles BS, Teng CC. Glutaric aciduria: a ‘new’ disorder of amino acid metabolism. Biochem Med. 1975;12:12–21. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(75)90091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann GF, Bohle’s HJ, Burlina A, Duran M, Herwig J, Lehnert W, et al. “Early signs and course of disease of glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency”. J Inherited Metab Dis. 1995;18:173–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00711759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amir N, el-Peleg O, Shalev RS, Christensen E. Glutaric aciduria type I: clinical heterogeneity and neuroradiologic features. Neurology. 1987;37:1654–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.10.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharawat IK, Dawman L. Glutaric aciduria type 1 with microcephaly: masquerading as spastic cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2018;13:349–51. doi: 10.4103/JPN.JPN_79_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muranjan MN, Kantharia V, Bavdekar SB, Ursekar M. Glutaric aciduria type-1. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38:1148–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elster AW. Glutaric aciduria type I: value of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosing acute striatal necrosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:98–100. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200401000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strauss KA, Lazovic J, Wintermark M, Morton DH. Multimodal imaging of striatal degeneration in Amish patients with glutaryl-coa dehydrogenase deficiency. Brain. 2007;130:1905–20. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamate M, Patil V, Chetal V, Darak P, Hattiholi V. Glutaric aciduria type I: a treatable neurometabolic disorder. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15:31–4. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.93273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaik M, Kamate M, Kruthika-Vinod TP, Vedamurthy AB. A low-excretor biochemical phenotype of glutaric aciduria type I: identification of novel mutations in the glutaryl coA dehydrogenase gene and review of literature from India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2019 doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_188_19. 10.4103/aian. AIAN_188_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]